Abstract

HIV remission trials often require temporary stopping of antiretroviral therapy (ART)—an approach called analytic treatment interruption (ATI). Trial designs resulting in viremia raise risks for participants and sexual partners. We conducted a survey on attitudes about remission trials, comparing ART resumption criteria (lower-risk “time to rebound” and higher-risk “sustained viremia”) among participants from an acute HIV cohort in Thailand. Analyses included Wilcoxon-Ranks and multivariate logistic analysis. Most of 408 respondents supported ATI trials, with slightly higher approval of, and willingness to participate in, trials using time to rebound versus sustained viremia criteria. Less than half of respondents anticipated disclosing trial participation to partners and over half indicated uncertainty or unwillingness about whether partners would be willing to use PrEP. Willingness to participate was higher among those who rated higher trial approval, lower anticipated burden, and those expecting to make the decision independently. Our findings support acceptability of ATI trials among most respondents. Participant attitudes and anticipated behaviors, especially related to transmission risk, have implications for future trial design and informed consent.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The design of many early phase HIV remission or “cure” trials requires that participants whose virus is well-controlled with antiretroviral therapy (ART) temporarily stop the drugs under close monitoring. This allows evaluation of the efficacy of the experimental agent(s)—an approach called analytic treatment interruption (ATI) [1]. ATI raises concerns about potential harms associated with both the experimental agent and being off ART, despite the relatively short time of viremia allowed in most past trials before re-initiating ART [2].

Our interviews with SEARCH010/RV254 (South East Asia Research Collaboration in HIV in Bangkok, hereafter called RV254) participants, a large group of acutely-diagnosed and immediately treated individuals in Thailand from which HIV remission trials with ATI recruited [3], have contributed to ethical discussions around ATI. We identified motivations and responses to trial participation that, for the most part, indicated that consent was voluntary and informed, though most participants had high expectations for personal and scientific benefit [4, 5]. Concurrently, ethical concerns about risk/benefit ratio have become more nuanced as data from early remission trials have demonstrated minimal or no adverse clinical impact of short periods of ATI [6, 7].

Unfortunately, no early remission trials were successful in durably controlling the virus. Most remission trial participants from RV254 experienced rapid viral load rebound and resumed ART; for four trials conducted through RV254, rebound was at confirmed HIV-1 RNA > 1000 copies/mL (this type of design is hereafter termed “time to rebound”). One question is whether trial design contributed to failure, as pre-clinical [8] and clinical studies [9] suggest that the immune system may require longer and/or stronger viral stimulation to mount an effective response. Hence, alternate trial designs are being developed, including designs in which participants remain off of ART for a prolonged period of time while virus levels meet or exceed a set point, such as 10,000 copies/mL (hereafter termed “sustained viremia”). Such designs with different set points are now being employed to assess HIV remission trial outcomes.

Designs that result in higher levels of viremia and/or viremia that extends for a longer time during ATI carry increased potential risks to participants and their partners. Risks include acute retroviral syndrome, drug resistance, viremia-associated longer-term health problems, as well as HIV transmission [10]. A 2018 survey of 85 community advocates ranked risk of transmission to an HIV-negative partner as the greatest concern of ATI trials [11]. Deepening this concern are data from French and Spanish ATI trials that document transmission events [12, 13].

Clinical trials that include sustained viremia are therefore marked by strong tension between important ethical principles. This type of ATI may be ethically justified on a consequentialist view that seeks to maximize the scientific value of research and potential future benefits for people living with HIV (PLHIV). But it also raises deontological concerns about the welfare of individual participants by increasing risks to their health [14] and the health of their partners [15, 16]. In light of these tensions, how should such trials be conducted? Some [4, 17, 18] argue that participant values and attitudes should help guide recommendations, and therefore, efforts to answer these vital questions should be supported by data from participants and potential participants in HIV remission trials.

Several studies, in addition to our own, have documented attitudes of PLHIV toward trials with ATI. Dubé et al. [19] found that more than 50% of 400 PLHIV surveyed in the US were willing to participate in hypothetical remission (“cure”) studies, most of whom indicated willingness to interrupt ART treatment as part of HIV cure research. In interviews about hypothetical ATI studies that included PLHIV in the US, Dubé et al. [20] found that risks related to viral rebound were the most prevalent concerns associated with ATI. Protière and colleague’s study, which included PLHIV in France, used Q-sort methodology to explore motivations and barriers to remission trial participation with ATI. They found that over 60% were willing to participate, and for the majority, an ART-free period of less than 6 months was acceptable [21]. A subsequent discrete choice experiment conducted in France assessed which HIV remission trial design factors influenced acceptability. Their results indicated that, among PLHIV, the potential for severe side effects had higher relative importance to trial acceptability than other factors, including trial outcomes (ATI duration and chance of success) and trial duration [22]. In their survey that included 442 PLHIV, Lau et al. [14] reported that the most concerning aspect related to remission trials with ATI was transmission risk, and that 34% would only participate in an ATI if their viral load remained undetectable. Of respondents, 26% reported ever “stopping ART” for any reason, though only 7% of those stopped ART as part of a study [14]. People who had ever interrupted ART were more willing to accept a detectable viral load during ATI [14]. No existing studies have compared predictors of willingness to participate in ATI trials with different ART restart criteria, nor willingness to engage in activities to reduce transmission risk for each trial type.

In this paper, we present data from a survey of RV254 cohort members on attitudes about ATI trials with different criteria for restarting ART—time to rebound and sustained viremia. We utilize our prior qualitative findings to anticipate factors associated with willingness to enroll, including anticipated benefit to self or others, the Thai Buddhist concept of “making merit” with an altruistic act, and trust in the clinical staff to keep them safe; and factors associated with declining a trial including poorer health, feeling relatively satisfied with ART, concern about possible health risks, and perceiving themselves to be at increased risk of infecting partners [4, 5]. Few studies have examined associations between intention to join ATI trials and factors such as HIV burden, ART adherence, disclosure, or sexual risk behaviors. However, our prior interview data suggest their possible importance [4, 5]. Lastly, by presenting results for two scenarios of ATI with different restart criteria, we contribute data that differentiate attitudes based on trial design. Data collection from the RV254 cohort allows us to assess attitudes and willingness from PLHIV for whom recruitment to an ATI trial may have already occurred, and/or for whom recruitment is a reasonable possibility. Five trials with ATI have already been conducted in this cohort and other trials are planned.

Methods

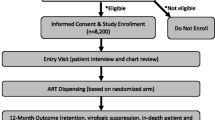

All participants were enrolled from the RV254 research cohort, which was established in 2009 by the US Military HIV Research Program (MHRP) (clinicaltrials.gov NCT00796146) in collaboration with the Thai Red Cross AIDS Research Centre (TRCARC) in Bangkok [6]. RV254 participants are acutely-infected individuals who consent to cohort participation are then placed on antiretroviral treatment (ART) immediately.

We conducted an online survey of the RV254 cohort using Qualtrics. Recruitment took place at regular clinical research visits (typically conducted every 3 to 6 months) from September 2019 to December 2019. The study nurses invited 597 cohort members to participate. Participants completed the survey in 30–45 min using their own smart phones or using a device in the clinic. Compensation was 500 Baht (approximately 15 USD). All participants provided informed consent to participate in the survey and to allow linkage to a limited subset of respondents’ RV254 clinical data. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University (#287/58).

The study addresses two research questions:

Are there differences in attitudes toward and willingness to participate in ATI trials with different criteria to restart ART?

and

What factors are associated with willingness to participate in trials that include ATI?

Measures

The survey included 71 validated and novel items that stemmed from our prior qualitative work and the research literature. Variables included in this report are described below.

Health- and HIV-Related Characteristics

These included a self-rating of general health status on a 5-point scale [23]; viral load; and self-report of having been invited by the clinical team to consider joining any of the five completed RV254 remission trials.

Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire (IPQ)

We adapted and customized to HIV the brief IPQ [24] to eight questions on a scale of 0 to 10. A summed score was created in accordance with published guidance [24]. The questions include ratings of consequence of HIV for their lives, length of time they anticipate having HIV, personal control, treatment control, extent of symptoms, level of concern, level of understanding, and emotional impact of HIV.

ART Attitudes and Adherence

One novel question queried whether being on ART lets participants “feel normal again” (reverse scored on a scale 0 to 10); the item was supported by our past work [4, 5, 25]. An ART adherence question modified from Knobel et al. [26] was used to query frequency of missed doses.

Disclosure and Transmission-Related Items

The survey assessed the number of people to whom HIV status had been disclosed; categories of people to whom it was disclosed (e.g., family, friends); and the number of sexual partners in the past 30 days—each of which was based on Khawcharoenporn et al. [27]. An additional item assessed likelihood of sexual transmission based on current viral load, on a 5-point scale (derived from Golin et al. [28]).

Attitudes About Remission Trials Employing ATI

Respondents were provided with two scenarios about being invited to a new experimental trial (see Appendix 1). The first vignette indicated that: “The first time your viral load increases above 1000 copies/mL, you would restart ART….For most people, this would be about 2 months after stopping ART, although a few people may stay off ART longer.” We call this the “time to rebound” ATI vignette.

The second vignette differed in the restart criteria and was intentionally designed to reflect a riskier scenario: “Your viral load would be allowed to go over 1000 copies/mL to see if your own immune system would start to fight the HIV virus on its own. If your viral load stays above 1000 copies/mL for 4 weeks in a row, you would restart ART. As long as your viral load does NOT go over 1000 copies/mL for 4 weeks in a row, you would continue to stay off ART and be monitored weekly.” We call this vignette the “sustained viremia” ATI vignette.

We used the Thai language equivalent to remission and did not use cure terminology. Our prior data from those who participated in and declined RV254 remission trials [4, 5] was used to develop a series of attitude and willingness statements (Table 3). After reading each trial scenario, participants were asked to respond to 13 attitude statements using a four-point scale. Next, participants were asked three questions, using a five-point scale, about anticipated willingness to disclose trial participation to partners, practice safe sex or abstain from sex during ATI, and to ask partners to use PrEP during ATI.

Respondents reported their RV254 identifier during the survey, which permitted linkage to a limited subset of respondents’ RV254 clinical data: sex, whether participants self-identify as men who have sex with men (MSM), age (in years), education level, time since entry into RV254 (which is highly concordant with the time that ART was initiated), and whether participants had also participated in an RV254 remission trial.

Analysis

Analyses were performed using SAS software (version 7.15). Univariate analysis was used to describe the study population using frequencies and proportions for categorical/ordinal variables and median and interquartile range (Q1 and Q3) to account for skewed distributions. Differences in attitudes and willingness between the scenarios with different ART restart criteria were tested using Wilcoxon Signed-Ranks test, with a significance level of p-value < 0.05. To identify variables associated with willingness to join the remission trials, we first dichotomized the willingness and attitudes questions (“agree” vs. “disagree”). We then conducted a series of univariate prefiltering logistic regression analyses that included the variables described in the measures section as well as the RV254 clinical data described above at α = 0.05 significance level. All variables significant in the univariate prefiltering analysis were included in the final multivariate logistic models.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

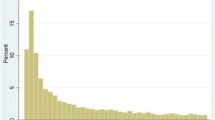

Of 597 invited, 408 RV254 members participated, with a response rate of 68%. The majority of respondents were male (98%) and MSM (94%). The median age was 30 and the median time since ART initiation was 3.7 years. Sixty-three percent of respondents had at least a 4-year degree. Most (73%) rated their health as “Excellent” or “Very good”. Forty-six percent responded that they had been invited to participate in a remission trial. Based on RV254 clinical data, 39 survey respondents had participated in a remission trial before taking the survey (see Table 1).

Comparing our survey respondents to the overall RV254 cohort (data not shown) in terms of age, sex at birth, sexual orientation, time since entry to RV254 and ART initiation, and frequency of viral load less than 20 copies/mL, we found significant differences only in time since entry to RV254, at 198.7 weeks (SD 124.4) in the survey population versus 230.2 weeks (SD 126.2) in the RV254 cohort, p < 0.0001.

Twenty-six percent of respondents reported having disclosed their HIV status to no one; 22% to only one person, and 37% to more than 2 persons (median = 3). Most (89%) reported never missing a dose of ART in the past week. Thirty-one percent reported no sexual partners in the past 30 days, and 40% reported one. Most (63%) rated the risk of transmission if they had sex ‘today’ as no chance or low chance, though a significant minority (29%) rated that they had a high or medium risk to transmit (see Table 2).

The 74% who indicated having disclosed their HIV status were then asked to whom they disclosed. Among those who disclosed, 128 (43%) told family, 182 (61%) told friends, and 160 (54%) told their sexual partner(s).

- Question #1:

-

Are there differences in attitudes toward and willingness to participate in ATI trials with different criteria to restart ART?

In response to the two hypothetical scenarios using time to rebound and sustained viremia designs, most participants rated approval of RV254 clinical researchers conducting remission trials, and willingness to enroll in both types of trials (see Fig. 1).

Over 90% agreed or strongly agreed that they would approve of time to rebound trials while 85% agreed or strongly agreed that they would approve of sustained viremia trials. Participants rated the ATI trial using time to rebound criteria slightly but significantly more acceptable than one using sustained viremia criteria (S = 2485.5, p < 0.0001). Eighty-eight percent of participants were willing to join the time to rebound trial compared to 68% for sustained viremia trial. Respondents were more likely to join a trial with time to rebound (S = 2614.5, p < 0.0001), rated that it would be easier to decide to join such a trial (S = 1471.5, p < 0.0001), and would feel safer in participating (S = 1678.0, p < 0.0001). Respondents also anticipated that a trial with sustained viremia would be more burdensome (S = − 1580.5, p < 0.0001) and would make them worry more (S = − 3396, p < 0.0001) than a trial with time to rebound criteria. For both trial types, respondents overall endorsed altruistic reasons to join, as well as an expectation that the experimental intervention would boost their immune system. Most agreed they would make the decision about whether to join independently, and that they would be concerned about transmission risk during the trials. When asked if declining the trial would let the clinical team down, most did not agree (see Table 3).

Table 4 includes responses about anticipated partner disclosure and transmission risk reduction during ATI trials. For both trial types, the large majority reported they would definitely or probably be able to practice safe sex or abstain from sex the entire time they were off ART (87% for time to rebound trial and 88% for sustained viremia trial). Just under half indicated that they would or probably would tell partners that they were in a trial (47% for time to rebound trial and 48% for sustained viremia). When asked if HIV-negative partners would use PrEP during ATI, slightly under half indicated their partners would be willing or very willing (45% for time to rebound trial and 46% for sustained viremia trial). The mean responses were identical between the scenarios for anticipated trial disclosure and safe sex/abstinence, and not significantly different for anticipated partner willingness to take PrEP.

- Question #2:

-

What factors are associated with willingness to participate in ATI trials?

Table 5 shows the final multivariate logistic models for factors that were significantly associated with willingness to enroll in ATI trials that use time to rebound and those that use sustained viremia. Variables included in the multivariate model were significant in the preliminary, univariate prefiltering analysis. For both trial scenarios, those who approved of the RV254 study team conducting the trial and those who agreed that they would make the decision by themselves were significantly more willing to participate than those who disagreed (approved of the trial: odds ratio [OR] 5.41; < 0.01 for time to rebound and OR 15.39; < 0.0001; would make the decision by themselves: OR = 3.70; p < 0.05 for time to rebound and OR = 10.74; p < 0.01 for sustained viremia). Those who agreed that participating would be too burdensome were less willing to participate than those who disagreed (OR = 0.14; p < 0.0001 for time to rebound and OR = 0.07; p < 0.0001 for sustained viremia). For the time to rebound scenario only, those who agreed they would feel safe due to trial monitoring and those who agreed that they would be excited about joining were significantly more willing to participate than those who disagreed (OR = 5.95; p < 0.01. and OR = 3.36; p < 0.01 respectively). For the sustained viremia scenario only, those who agreed that it would be easy to decide whether to join were significantly more willing to participate than those who disagreed (OR = 4.65; p < 0.001).

Discussion

Our study, like several others [14, 19, 20], documents relatively positive attitudes about and willingness to participate in remission trials with ATI. Our study provides a perspective that has not previously been systematically assessed—that is, attitudes about remission trials with different criteria for restarting ART, which are associated with different degrees of risk for participants and their sexual partners. Our participants are individuals in an established cohort that has been, and will continue to be, a source of recruitment of remission trials. We found slightly but significantly higher approval of and willingness to participate in trials that restart ART based on time to rebound (the design associated with lower participant risk) versus trials that result in sustained viremia (the design associated with higher participant risk), though most respondents were positive about both types of trials. A follow up study might further explore the attitudes of the approximately 15–30% of participants who would either not support these studies being conducted or are not willing to participate.

There were small differences between the trial types in anticipated ease of decision making, feeling safe in the trial, trial burden, and trial worry. Though our findings illustrate that participants differentiated between the ART resumption criteria described in the vignettes, the difference in attitudes between the two trial types were small and may not be meaningfully different in a clinical research context. We conclude that respondents had, overall, positive attitudes about both trial types.

In response to both scenarios, participants endorsed, overall, positive expectations of personal and altruistic benefits that did not significantly differ between scenarios. In addition, participants overall disagreed that declining trial participation would be letting down the clinical research team. In prior interviews with RV254 trial participants and decliners [4, 5], many reported a pull to reciprocate to the clinical team and yet ultimately felt empowered to make an autonomous decision.

Regarding willingness to participate for both trial scenarios, as we expected, those approving of the research team conducting the trials and not anticipating excessive trial burden reported being more willing to participate than those who did not hold those attitudes. Those anticipating making the trial decision independently were more willing to enroll than those who do not, a finding which reflects the importance across trial types of anticipating oneself to be able to make an autonomous, individual decision. Those indicating feeling safe in the trial and being excited about joining were more willing to join trials that use time to rebound but not those resulting in sustained viremia, suggesting increased caution and a tempering of excitement associated with ART restart criteria. That increased caution is also reflected in the finding that those who report the decision would be easy are more willing to join trials of fixed duration. Surprisingly, factors associated with willingness to participate did not include self-reported general health status, HIV burden, ART adherence, or having been invited to a SEARCH remission trial.

We found the disclosure and transmission data overall to raise some concerns and areas for future research. Participants reported equal concern about transmission to partners for both ATI scenarios. Many do not disclose their HIV status to partners, which is a major barrier to transmission risk reduction. Furthermore, although nearly all respondents had undetectable viral loads, the self-assessment of transmission risk was higher than expected, with about a third indicating a medium or high transmission risk “today.” This may indicate misunderstanding and/or reflect Thai social concerns [29]. Our prior work suggests additional explanations that may be acting in tandem, which may require additional supportive interventions: the impact of internalized stigma together with an emotion-oriented representation of oneself as dangerous to partners. We are undertaking additional research to better understand relationships among perceived transmission risk, self-concept, and stigma [25].

Several recent publications have focused on risk to partners during ATI trials. Efforts may attempt to reduce the transmission risk and to increase the ethical justification of remaining risk through the use of restrictive inclusion criteria, education and counseling, and protective care for at-risk partners [16]. For near-complete risk mitigation to be achieved in ATI trials, participants would have to abstain from sex with HIV-negative partners, commit to condom use at every sexual encounter, disclose their trial participation and risk status, and/or their partners would have to use PrEP [16]. Other more extreme risk mitigation approaches have been proposed for consideration, such as isolation of study participants during ATI [30].

Upon assessing factors associated with willingness to participate, our data provided no support that disclosure patterns, self-assessed risk of transmission, or anticipated partner willingness to use PrEP impact willingness to participate in trials with ATI. To put it another way, we find no indication that RV254 participants would self-select out of trials based on their disclosure behaviors or perceptions of their transmission risk. A positive finding from our study is the very high percentage of participants who indicated that they would abstain or practice safe sex during an ATI trial. Additional research is needed on attitudes and behaviors of PLHIV and their at-risk partners.

Our study has several limitations. One is the use of hypothetical scenarios of remission trials with ATI, and more specifically, the framing of our two scenarios. These were complicated concepts to get across in an online survey. Though we took care to differentiate the scenarios, there were many similarities and some participants may not have appreciated the distinctions. For feasibility we provided relatively few details about the trial designs; e.g., in the sustained viremia scenario we did not identify an upper limit above which ART must be restarted immediately. Additionally, the second scenario is intentionally framed as riskier than the first, which might have influenced reported willingness and acceptability in ways that we cannot fully capture in this type of survey. An example that may reflect the survey limitations is that our evidence does not indicate differentiation of transmission risk between the ATI scenarios, even though the vignette provided in the survey describes an increased risk of transmission in the sustained viremia scenario. Finally, neither of our scenarios mention offering PrEP to partners in addition to the use of condoms or abstinence.

Though remission trials are highly salient to our study population, most respondents had not participated in remission trials, although nearly half reported that they had been invited to join one. (Given the small sample, our analyses could not incorporate actual remission trial participation as a predictor.) A further limitation is generalizability of our findings to other PLHIV given RV254 characteristics. We expect that research interest and endorsement of trials with ATI will be higher among participants in existing cohorts like RV254 compared to those not part of research cohorts [31]. Most studies of ATI in the literature are based on convenience samples. Unlike convenience sampling, however, the RV254 cohort characteristics are well described. Though our response rate was reasonably high for a survey, nearly 30% declined participation, resulting in respondents with significantly less time since entry to RV254. More data should be collected in different settings and with different types of potential participants.

Our study reinforces the need for targeted education and strong informed consent for trials with ATI to focus attention on the low chance of personal benefit, the potential for harm to self, and potential risk to sexual partners. Our data related to disclosure and transmission risk may also have implications for inclusion criteria for trials with sustained viremia. Several authors have asked whether it is ethically justified to conduct ATI studies if participation is not systematically disclosed to partners, who may be exposed to HIV transmission without their knowledge and without being able to protect themselves [15, 16]. This puts considerable additional responsibility on the participant and the research team, as well as on sexual partners who are not engaged in the research. Requirements of disclosure and safe sex practices are challenging to implement and may stress the trust relationship between participants and clinical researchers. Additional evidence-informed guidance is needed to test and refine ethical models to implement remission trials with extended periods of ATI.

Data Availability

De-identified data are available upon request.

Code Availability

Code is available upon request.

References

Wen Y, Bar KJ, Li JZ. Lessons learned from HIV antiretroviral treatment interruption trials. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1097/COH.0000000000000484.

Eyal N, Holtzman LG, Deeks SG. Ethical issues in HIV remission trials. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2018;13(5):422–7.

Muccini C, Crowell TA, Kroon E, Sacdalan C, Ramautarsing R, Seekaew P, et al. Leveraging early HIV diagnosis and treatment in Thailand to conduct HIV cure research. AIDS Res Ther. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12981-019-0240-4.

Henderson GE, Peay HL, Kroon E, Cadigan RJ, Meagher K, Jupimai T, et al. Ethics of treatment interruption trials in HIV cure research: addressing the conundrum of risk/benefit assessment. J Med Ethics. 2018;44(4):270–6.

Henderson GE, Waltz M, Meagher K, Cadigan RJ, Jupimai T, Isaacson S, et al. Going off antiretroviral treatment in a closely monitored HIV “cure” trial: longitudinal assessments of acutely diagnosed trial participants and decliners. J Int AIDS Soc. 2019;22(3):e25260.

Crowell TA, Colby DJ, Pinyakorn S, Sacdalan C, Pagliuzza A, Intasan J, et al. Safety and efficacy of VRC01 broadly neutralising antibodies in adults with acutely treated HIV (RV397): a phase 2, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet HIV. 2019;6(5):e297–306.

Stecher M, Claßen A, Klein F, Lehmann C, Gruell H, Platten M, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of treatment interruptions in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type 1–infected patients receiving antiretroviral therapy: implications for future HIV cure trials. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;70(7):1406–17. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciz417.

Borducchi EN, Cabral C, Stephenson KE, Liu J, Abbink P, Ng’ang’a D, et al. Ad26/MVA therapeutic vaccination with TLR7 stimulation in SIV-infected rhesus monkeys. Nature. 2016;540(7632):284–7.

Sneller MC, Justement JS, Gittens KR, Petrone ME, Clarridge KE, Proschan MA, et al. A randomized controlled safety/efficacy trial of therapeutic vaccination in HIV-infected individuals who initiated antiretroviral therapy early in infection. Sci Transl Med. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.aan8848.

Julg B, Dee L, Ananworanich J, Barouch DH, Bar K, Caskey M, et al. Recommendations for analytical antiretroviral treatment interruptions in HIV research trials—report of a consensus meeting. Lancet HIV. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(19)30052-9.

Jefferys R. Community recommendations for clinical research involving antiretroviral treatment interruption in adults. 2018. https://www.treatmentactiongroup.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/community_recs_clinical_research_final.pdf. Accessed 11 Oct 2021.

Palich R, Ghosn J, Chaillon A, Boilet V, Nere M-L, Chaix M-L, et al. Viral rebound in semen after antiretroviral treatment interruption in an HIV therapeutic vaccine double-blind trial. AIDS. 2019;33(2):279–84. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000002058.

Ugarte A, Romero Y, Tricas A, Casado C, Lopez-Galindez C, Garcia F, et al. Unintended HIV-1 infection during analytical therapy interruption. J Infect Dis. 2020;221(10):1740–2. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiz611.

Lau JSY, Smith MZ, Allan B, Martinez C, Power J, Lewin SR, et al. Perspectives on analytical treatment interruptions in people living with HIV and their health care providers in the landscape of HIV cure-focused studies. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1089/aid.2019.0118.

Eyal N, Deeks SG. Risk to nonparticipants in HIV remission studies with treatment interruption: a symposium. J Infect Dis. 2019;220(220 Suppl 1):S1–4.

Peluso MJ, Dee L, Campbell D, Taylor J, Hoh R, Rutishauser RL, et al. A collaborative, multidisciplinary approach to HIV transmission risk mitigation during analytic treatment interruption. J Virus Erad. 2020;6(1):34–7.

Evans D. An activist’s argument that participant values should guide risk-benefit ratio calculations in HIV cure research. J Med Ethics. 2017;43(2):100–3.

Peay HL, Henderson GE. What motivates participation in HIV cure trials? A call for real-time assessment to improve informed consent. J Virus Erad. 2015;1(2):51–3.

Dubé K, Evans D, Sylla L, Taylor J, Weiner BJ, Skinner A, et al. Willingness to participate and take risks in HIV cure research: survey results from 400 people living with HIV in the US. J Virus Erad. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2055-6640(20)30295-8.

Dubé K, Evans D, Dee L, Sylla L, Taylor J, Skinner A, et al. “We need to deploy them very thoughtfully and carefully”: perceptions of analytical treatment interruptions in HIV cure research in the United States-a qualitative inquiry. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 2018;34(1):67–79.

Protière C, Spire B, Mora M, Poizot-Martin I, Préau M, Doumergue M, et al. Patterns of patient and healthcare provider viewpoints regarding participation in HIV cure-related clinical trials. Findings from a multicentre French survey using Q methodology (ANRS-APSEC). PLoS ONE. 2017;12(11):e0187489–e0187489.

Protiere C, Arnold M, Fiorentino M, Fressard L, Lelièvre JD, Mimi M, et al. Differences in HIV cure clinical trial preferences of French people living with HIV and physicians in the ANRS-APSEC study: a discrete choice experiment. J Int AIDS Soc. 2020;23(2):e25443–e25443.

CDC. National health and nutrition examination survey. CDC. 2015. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/2013-2014/HSQ_H.htm. Accessed 11 Oct 2021.

Broadbent E, Petrie K, Main J, Weinman J. The brief illness perception questionnaire (BIPQ). J Psychosom Res. 2006;1(60):631–7.

Peay, H.L., Jupimai, T., Ormsby, N., Rennie, S., Cadigan, R.J, Kuczynski, K., Isaacson, S.C., Phanuphak, N., Kroon, E., Ananworanich, J., Vasan, S., Prueksakaew, P., Intasan, J., Henderson GE. Perceived health and stigma among a population of individuals diagnosed with acute HIV: report from the SEARCH010 cohort. In: AIDS 2020: virtual [conference presentation]. San Francisco: International AIDS Society.

Knobel H, Alonso J, Casado JL, Collazos J, González J, Ruiz I, et al. Validation of a simplified medication adherence questionnaire in a large cohort of HIV-infected patients: the GEEMA Study. AIDS. 2002. https://doi.org/10.1097/00002030-200203080-00012.

Khawcharoenporn T, Chunloy K, Apisarnthanarak A. Uptake of HIV testing and counseling, risk perception and linkage to HIV care among Thai university students. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:556.

Golin CE, Earp JA, Grodensky CA, Patel SN, Suchindran C, Parikh M, et al. Longitudinal effects of SafeTalk, a motivational interviewing-based program to improve safer sex practices among people living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(5):1182–91.

Phanuphak N, Ramautarsing R, Chinbunchorn T, Janamnuaysook R, Pengnonyang S, Termvanich K, et al. Implementing a status-neutral approach to HIV in the Asia-pacific. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2020;17(5):422–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11904-020-00516-z.

Eyal N, Magalhaes M. Is it ethical to isolate study participants to prevent HIV transmission during trials with ananalytical treatment interruption? J Infect Dis. 2019;220(220 Suppl 1):S19–21. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiz164.

Henderson GE, Rennie S, Corneli A, Peay HL. Cohorts as collections of bodies and communities of persons: insights from the SEARCH010/RV254 research cohort. Int Health. 2020;12(6):584–90.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our study participants.

Funding

The study was funded in entirety by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (1R01AI127024). The investigators acknowledge expert input supported by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Center for AIDS Research (P30 AI50410). The participants were from the RV254/SEARCH 010, which is supported by cooperative agreements (WW81XWH-18-2-0040) between the Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine, Inc., the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD), an intramural grant from the Thai Red Cross AIDS Research Centre, and by the U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Antiretroviral therapy for RV254/SEARCH 010 participants was supported by the Thai Government Pharmaceutical Organization, Gilead, Merck and ViiV Healthcare. The funding sources have no involvement in study design, data collection and analysis, or writing the report.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design or the acquisition, analysis or interpretation of the data. Conceptualization and methodology were led by HP and GH. Data collection was led by TJ with support by PP and KB, with supervision by EK and DC. Analysis were performed by AG and HP. The first draft of the manuscript was written by HP, TJ, NO and GH, and all authors reviewed and revised previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript version to be published. All authors agree to be accountable for the work and ensure any questions about the accuracy or integrity are investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

DC has received research grant support from Gilead Sciences. All other authors report no conflicts of interest or competing interests.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the IRB of the Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University.

Consent to Participate

All participants provided informed consent to participate in the study.

Consent for Publication

The study informed consent included a section indicating that de-identified study data would be reported.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Disclaimer The views expressed are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent the positions of the U.S. Army or the Department of Defense. The investigators have adhered to the policies for protection of human subjects as prescribed in AR 70–25.

Appendix 1 Remission trial vignettes utilized in RV254 (SEARCH010) survey to assess trial attitudes and willingness to participate

Appendix 1 Remission trial vignettes utilized in RV254 (SEARCH010) survey to assess trial attitudes and willingness to participate

ATI vignette 1 Now, imagine you are invited to a new SEARCH 010 remission trial. It would test whether a new kind of experimental drug boosts the immune system, and if it is safe. You would get the experimental drug and then stop taking ART. You would come to SEARCH weekly for monitoring. The first time your viral load increases above 1000 copies/mL, you would restart ART About the experimental drug: Safety: The experimental drug would probably be safe, but researchers wouldn’t know for sure Side effects: You may have mild side effects While off ART: Monitoring at SEARCH: You would visit SEARCH once a week for health exams and blood draws to monitor your health, viral load, and CD4 count Side effects: You would probably not develop HIV symptoms or drug resistance. Longer term side effects are unknown Transmission risk: Your risk of transmitting HIV to partners might increase Re-starting ART: Viral load: People restart ART when their viral load increases above the trial’s limit (1000 copies/mL). For most people, this would be about 2 months after stopping ART, although a few people may stay off ART longer Researchers expect that once people restart ART, their viral load should decrease and become undetectable Long term monitoring: The SEARCH team would continue to monitor your health once a month for a year | ATI vignette 2 Now imagine there is a different type of SEARCH remission trial. This one keeps you off ART longer, which is riskier. This extra time off ART would test whether your immune system can recognize and kill the virus. The SEARCH team would check how your viral load goes up and down over time Like the first trial, You would get the same new experimental drug and then stop ART You would come in for a weekly health exam and blood draw If you have serious side effects from stopping ART at any time, you would immediately restart ART Once you restart ART, your viral load should decrease, and you should become undetectable again Once you restart ART, the SEARCH team would continue to monitor your health once a month for 1 year Different from the first trial Your viral load would be allowed to go over 1000 copies/mL to see if your own immune system would start to fight the HIV virus on its own If your viral load stays above 1000 copies/mL for 4 weeks in a row, you would restart ART As long as your viral load does NOT go over 1000 copies/mL for 4 weeks in a row, you would continue to stay off ART and be monitored weekly You would be at much higher risk of transmitting HIV to your partner(s), so you would need to use condoms or abstain from sex |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Peay, H.L., Rennie, S., Cadigan, R.J. et al. Attitudes About Analytic Treatment Interruption (ATI) in HIV Remission Trials with Different Antiretroviral Therapy (ART) Resumption Criteria. AIDS Behav 26, 1504–1516 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-021-03504-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-021-03504-5