Abstract

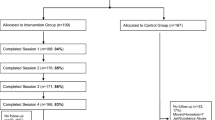

There is a need for brief HIV prevention interventions that can be disseminated and implemented widely. This article reports the results of a small randomized field experiment that compared the relative effects of a brief two-session counselor-delivered computer-tailored intervention and a control condition. The intervention is designed for use with African-American, non-Hispanic white and Hispanic males and females who may be at risk of HIV through unprotected sex, selling sex, male to male sex, injecting drug use or use of stimulants. Participants (n = 120) were recruited using a quota sampling approach and randomized using block randomization, which resulted in ten male and ten female participants of each racial/ethnic group (i.e. African-American, non-Hispanic white and Hispanic) being assigned to either the intervention or a control arm. In logistic regression analyses using a generalized estimating equations approach, at 3-month followup, participants in the intervention arm were more likely than participants in the control arm to report condom use at last sex (Odds ratio [OR] = 4.75; 95 % Confidence interval [CI] = 1.70–13.26; p = 0.003). The findings suggest that a brief tailored intervention may increase condom use. Larger studies with longer followups are needed to determine if these results can be replicated.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

CDC Compendium of evidence-based HIV behavioral interventions: risk reduction chapter, 2012.

Coury-Doniger P, et al. HIV prevention interventions for black MSM. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(2):198.

Crepaz N, et al. The efficacy of HIV/STI behavioral interventions for African-American females in the United States: a meta-analysis. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(11):2069–78.

Darbes L, et al. The efficacy of behavioral interventions in reducing HIV risk behaviors and incident sexually transmitted diseases in heterosexual African-Americans. AIDS. 2008;22(10):1177–94.

Herbst JH, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of behavioral interventions to reduce HIV risk behaviors of Hispanics in the United States and Puerto Rico. AIDS Behav. 2007;11(1):25–47.

Lyles CM, et al. Best-evidence interventions: findings from a systematic review of HIV behavioral interventions for US populations at high risk, 2000–2004. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(1):133–43.

Owczarzak J, Dickson-Gomez J. Provider perspectives on evidence-based HIV prevention interventions: barriers and facilitators to implementation. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2011;25(3):171–9.

Rietmeijer CA. The max for the minimum: brief behavioral interventions can have important HIV prevention benefits. Aids. 2003;17(10):1561–2.

Kelly JA, Spielberg F, McAuliffe TL. Defining, designing, implementing, and evaluating phase 4 HIV prevention effectiveness trials for vulnerable populations. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;47(Suppl 1):S28–33.

Veniegas RC, et al. HIV prevention technology transfer: challenges and strategies in the real world. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(Suppl 1):S124–30.

Noar SM, et al. Using computer technology for HIV prevention among African-Americans: development of a tailored information program for safer sex (TIPSS). Health Educ Res. 2011;26(3):393–406.

Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31(2):143–64.

Bandura A. Perceived self-efficacy in the exercise of control over AIDS infection. Eval Progr Plan. 1990;13(1):9–17.

Bandura A. Self-efficacy: the exercise of control. New York: W.H. Freeman and Company; 1997.

Latka MH, et al. A randomized intervention trial to reduce the lending of used injection equipment among injection drug users infected with hepatitis C. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(5):853–61.

Kamb ML, et al. Efficacy of risk-reduction counseling to prevent human immunodeficiency virus and sexually transmitted diseases: a randomized controlled trial. Project RESPECT Study Group. JAMA. 1998;280(13):1161–7.

Shain RN, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of a behavioral intervention to prevent sexually transmitted disease among minority women. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(2):93–100.

St Lawrence JS, et al. Cognitive-behavioral intervention to reduce African-American adolescents’ risk for HIV infection. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1995;63(2):221–37.

Latkin CA, Sherman S, Knowlton A. HIV prevention among drug users: outcome of a network-oriented peer outreach intervention. Health Psychol. 2003;22(4):332–9.

Metzger DS, et al. Randomized controlled trial of audio computer-assisted self-interviewing: utility and acceptability in longitudinal studies. HIVNET Vaccine Preparedness Study Protocol Team. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152(2):99–106.

Rogers SM, et al. Audio computer assisted interviewing to measure HIV risk behaviours in a clinic population. Sex Transm Infect. 2005;81(6):501–7.

Diggle P, et al. Analysis of longitudinal data. 2nd ed. Oxford statistical science series2002, Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. xv, p. 379.

Zeger SL, Liang KY. Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics. 1986;42(1):121–30.

Bobashev GV, et al. Transactional sex among men and women in the south at high risk for HIV and other STIs. J Urban Health. 2009;86(Suppl 1):32–47.

Austin PC. An introduction to propensity score methods for reducing the effects of confounding in observational studies. Multivar Behav Res. 2011;46(3):399–424.

D’Agostino RB Jr. Propensity score methods for bias reduction in the comparison of a treatment to a non-randomized control group. Stat Med. 1998;17(19):2265–81.

Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika. 1983;70(1):41–55.

Rubin DB. Propensity score methods. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010;149(1):7–9.

Scholes D, et al. A tailored minimal self-help intervention to promote condom use in young women: results from a randomized trial. AIDS. 2003;17(10):1547–56.

Gagnon H, et al. A randomized trial to evaluate the efficacy of a computer-tailored intervention to promote safer injection practices among drug users. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(3):538–48.

Langhaug LF, Sherr L, Cowan FM. How to improve the validity of sexual behaviour reporting: systematic review of questionnaire delivery modes in developing countries. Trop Med Int Health. 2010;15(3):362–81.

Gallo MF, et al. Predictors of unprotected sex among female sex workers in Madagascar: comparing semen biomarkers and self-reported data. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(6):1279–86.

Gallo MF, et al. Prostate-specific antigen to ascertain reliability of self-reported coital exposure to semen. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33(8):476–9.

Simoes AA, et al. A randomized trial of audio computer and in-person interview to assess HIV risk among drug and alcohol users in Rio De Janeiro Brazil. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2006;30(3):237–43.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the assistance of Steffanie Strathdee, Sebastian Bonner, Anita Raj, Rochelle Shain, Janet St. Lawrence, and Melissa Davey-Rothwell who shared their evidence-based interventions with us and granted us permission to incorporate elements of them into this intervention. This project was funded by NIH Grant number R21DA026771 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zule, W.A., Bobashev, G.V., Reif, S.M. et al. Results of a Pilot Test of a Brief Computer-Assisted Tailored HIV Prevention Intervention for Use with a Range of Demographic and Risk Groups. AIDS Behav 17, 3045–3058 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-013-0557-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-013-0557-2