Abstract

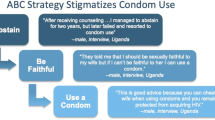

Common strategies employed in preventing STI/AIDS transmission among young adults in America include abstinence, monogamy and safer sex. These strategies require a high level of vigilance and responsibility and, according to inner city participants in Project PHRESH.comm, neither option is always desirable, available, or rational in the context of their lived experiences. This article reports findings from Project PHRESH.comm, a mixed-method, ethnographic study incorporating data from focus group discussions, semi-structured interviews, coital diaries, systematic cultural assessments and a structured survey designed to explore concepts of risk and decision making about condom use among at risk African American and Puerto Rican young adults aged 18–25 years in Hartford, CT. We found that many young adults from our study population rely on a strategy of using clinic-sponsored STI/AIDS screening when wanting to discontinue condom use with a partner. While our data suggest that screening is a common strategy used by many couples to transition to having sex without a condom, the data also show that most youth do not maintain monogamy even in long-term, serious relationships. Thus, sharing test results may provide a false sense of security in the sexual culture of inner city, minority youth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

This research was supported by Award Numbers U58/CCU123064 and U58/CCU323065 from the CDC. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of CDC or the Family Planning Council of Philadelphia.

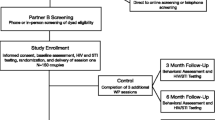

Participants were eligible if they met the universal eligibility criteria: age 18–25, had had sex with a member of the opposite sex in the last year, born in the United States or Puerto Rico, self-identified as African American or Puerto Rican, and spoke English (FGD, SCA, SI methods) or English or Spanish (SRI and CD methods—Hartford only). The language criteria were imposed for practical reasons to maintain consistency between the Hartford and Philadelphia sites. All Spanish interviews were translated into English. There were two SRIs and three CDs completed in Spanish; most Puerto Ricans in this age group spoke English. The CD method had more stringent eligibility criteria—having had sex at least three times in the last 30 days with a member of the opposite sex and having had sex with more than one person in the last 30 days. An additional eligibility criterion for SI participants was not having participated in any of the other PHRESH methods.

For our participants, the “lifetime” in question was 18–25 years.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Epidemiology of HIV/AIDS—United States, 1981–2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55:589–92. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5521a2.htm. Accessed 9 July 2010.

Institute of Medicine. The hidden epidemic: confronting sexually transmitted diseases. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1997.

Kirby D. The impact of abstinence and comprehensive sex and STD/AIDS education programs on adolescent sexual behavior. Sexuality research and social policy. J NSRC. 2008;5:18–27.

Santelli J, Ott M, Lyon M, et al. Abstinence and abstinence-only education: a review of U.S. policies and programs. J Adolesc Health. 2006;38:72–81.

Jemmott JB, Jemmott LS, Fong GT. Abstinence and safer sex HIV risk-infection interventions for African American adolescents: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Assoc. 1998;279:1529–36.

Anderson J, Wilson RD, Jones L, Stephen T, Barker P. Condom use and HIV risk behaviors among U.S. adults: data from a national survey. Fam Plann Perspect. 1999;31:24–8.

Katz B, Fortenberry JD, Zimet G, Blythe M, Orr D. Partner-specific relationship characteristics and condom use among young people with sexually transmitted diseases. J Sex Res. 2000;37:69–75.

Lichtenstein B, Desmond R, Schwebke J. Partnership concurrency status and condom use among women diagnosed with trichomonas vaginalis. Women Health Issues. 2008;18:369–74.

Singer M, Erickson P, Badiane L, Diaz R, Ortiz D, et al. Syndemics, sex and the city: understanding sexually transmitted diseases in social and cultural context. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63:2010–21.

Carey M, Senn T, Seward D, Vanable P. Urban African-American men speak out on sexual partner concurrency: findings from a qualitative study. AIDS Behav. 2010;14:38–47.

Brady S, Tschann J, Ellen J, Flores E. Infidelity, trust and condom use among Latino youth in dating relationships. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36:227–31.

Richards J, Risser J, Padgett P, et al. Condom use among high-risk heterosexual women with concurrent sexual partnerships, Houston, Texas, USA. Int J STD AIDS. 2008;19:768–71.

Doherty I, Shibowski S, Ellen J, Adimora A, Padian N. Sexual bridging socially and over time: a simulation model exploring the relative effects of mixing and concurrency viral sexually transmitted infection transmission. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33:363–73.

Morris M, Kurth A, Hamilton D, Moody J, Wakefield S. Concurrent partnerships and HIV prevalence disparities by race: linking science and public health practice. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:1023–31.

Jennings J, Glass B, Parham P, Alder N, Ellen J. Sex partner concurrency, geographic context, and adolescent sexually transmitted infections. Sex Transm Dis. 2004;31:734–9.

Santelli J, Brener N, Lowry R, Bhatt A, Zabin L. Multiple sexual partners among U.S. adolescents and young adults. Fam Plann Perspect. 1998;30:271–5.

Weinstock H, Berman S, Cates W. Sexually transmitted diseases among American youth: incidence and prevalence estimates. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2004;36:6–10.

Chatterjee N, Hosain M, Williams S. Condom use with steady and casual partners in inner city African-American communities. Sex Transm Infect. 2006;82:238–42.

Santelli J, Kouzis A, Hoover D, et al. Stage of behavior change for condom use: the influence of partner type, relationship and pregnancy factors. Fam Plann Perspect. 1996;28:101–7.

Ku L, Sonenstein F, Pleck J. The dynamics of young men’s condom use during and across relationships. Fam Plann Perspect. 1994;26:246–51.

Misovich S, Fisher J, Fisher W. Close relationships and elevated HIV risk behavior: evidence and possible underlying psychological processes. Rev Gen Psychol. 1997;1:72–107.

Watson W, Bell N. Narratives of development, experiences of risk: adult women’s perspectives on relationships and safer sex. Br J Health Psychol. 2005;10:311–27.

Marsten C, King E. Factors that shape young people’s sexual behaviour: a systematic review. Lancet. 2006;368:1581–6.

Frank M, Poindexter A, Cox CA, Bateman L. A cross-sectional survey of condom use in conjunction with other contraceptive methods. Women Health. 1995;23:31–46.

Salabarria-Pena Y, Lee J, Montgomery S, Hopp H, Muralles A. Determinants of female and male condom use among immigrant women of Central American descent. AIDS Behav. 2003;7:163–74.

Manuel S. Obstacles to condom use among secondary school students in Maputo city, Mozambique. Cult Health Sex. 2005;7:293–302.

Juarez F, Martín Castro T. Safe sex versus safe love? Relationship context and condom use among male adolescents in the favelas of Recife, Brazil. Arch Sex Behav. 2006;35:25–35.

Gilliam M, Reuler A, Berlin A. The role of relationship context in African American adolescent males’ condom decision-making. J Adolesc Health. 2007;40(Suppl 1):23–4.

Adimora A, Schoenbach V. Social context, sexual networks, and racial disparities in rates of sexually transmitted infections. J Infect Dis. 2005;191(Suppl 1):115–22.

Bernard R. Research methods in anthropology: qualitative and quantitative approaches. 4th ed. Lanham: AltaMira Press; 2006.

Macauda M, Erickson P, Santelices C, et al. Your cheating ways: the social construction of infidelity among inner city emerging adults. Poster presented at 136th annual meeting of the American Public Health Association, October 25–29, 2008, San Diego, CA.

Hatfield-Timajchy K, Andes K, Cassidy A, et al. Beyond polemics: the merits and challenges of assessing intercoder agreement in a qualitative research study. Poster presented at 137th annual meeting of the American Public Health Association, November 7–11, 2009, Philadelphia, PA.

Denzin N. The research act: theoretical introduction to sociological methods. Chicago: Aldine; 1970.

Kohler Riessman C. Narrative analysis, qualitative research methods. Series 30. Newbury Park: Sage Publications; 1993.

Morse JM. Designing funded qualitative research. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. Handbook of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1994. p. 220–35.

Handwerker P. Quick ethnography. Walnut Creek: AltaMira; 2001.

Worth D. Sexual decision-making and AIDS: why condom promotion among vulnerable women is likely to fail. Stud Family Plan. 1989;20:297–307.

Sobo E. Inner-city women and AIDS: the psycho-social benefits of unsafe sex. Cult Med Psychiatry. 1993;17:455–85.

Pivnick A. HIV infection and the meaning of condoms. Cult Med Psychiatry. 1993;17:431–53.

Fortenberry JD, Tu W, Harezlak J, Katz B, Orr D. Condom use as a function of time in new and established adolescent sexual relationships. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:211–3.

Rietmeijer C, Bemmelen R, Judson F, Douglas J. Incidence of repeat infection rates of chlamydia trachomatis among male and female patients in an STD clinic. Implications for screening and rescreening. Sex Transm Dis. 2002;29:65–72.

Golden M, Whittington W, Handsfield HH, Hughes J, Stamm W, Hogben M, et al. Effect of expedited treatment of sex partners on recurrent or persistent gonorrhea or chlamydial infection. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:676–85.

Tilson E, Sanchez V, Ford C, Smurzynski M, Leone P, Fox K, et al. Barriers to asymptomatic screening and other STD services for adolescents and young adults: focus group discussions. BMC Public Health. 2004;4:21–8.

Tolou-Shams M, Payne N, Houck C, Pugatch D, Beausoliel N, Brown L, et al. HIV testing among at-risk adolescents and young adults: a prospective analysis of a community sample. J Adolesc Health. 2007;41:586–93.

Gupta G, Weiss E. Women’s lives and sex: implications for AIDS prevention. Cult Med Psychiatry. 1993;17:399–412.

Taylor B. Gender-power relations and safer sex negotiation. J Adv Nurs. 1995;22:687–93.

Zierler S, Krieger N. Reframing women’s risk: social inequalities and HIV infection. Annu Rev Public Health. 1997;18:401–36.

Gorbach P, Stoner B, Aral S, Whittington W, Holmes KK. “It takes a village”: understanding concurrent sexual partnerships in Seattle, Washington. Sex Transm Dis. 2002;29:453–62.

Adimora A, Schoenbach V, Martinson F, Donaldson K, Stancil T, Fullilove R. Concurrent sexual partnerships among African Americans in the rural south. Ann Epidemiol. 2004;14:155–60.

Singer M. Desperate measures: a syndemic approach to the anthropology of health in a violent city. In: Rylko-Bauer B, Whiteford L, Farmer P, editors. Global health in times of violence. Sante Fe: SAR Press; 2009. p. 137–56.

Gunn R, Rolfs R, Greenspan J, Seidman R, Wasserheit J. The changing paradigm of sexually transmitted disease control in the era of managed health care. J Am Med Assoc. 1998;27:680–4.

Mehta S, Erbelding E, Zenilman J, Rompalo A. Gonorrhoea reinfection in heterosexual STD clinic attendees: longitudinal analysis of risks for first reinfection. Sex Transm Infect. 2003;79:124–8.

Trelle S, Shang A, Nartey L, Cassel J, Low N. Improved effectiveness of partner notification for patients with sexually transmitted infections: systematic review. BMJ. 2007;334:354.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations for partner services programs for HIV infection, syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydial infection. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2008;57:1–63.

Sonfield A. For some sexually transmitted infections, secondary prevention may be primary. Guttmacher Policy Rev. 2009;12:2. http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/gpr/12/2/gpr120202.pdf. Accessed 8 July 2010.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Advancing HIV prevention: new strategies for a changing epidemic—United States, 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52:52–539.

U.S. Preventative Services Task Force. Clinical guidelines: screening for Chlamydia infection U.S. Preventative Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:128–34.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the many people who contributed to this article. Drs. Pamela Erickson and Merrill Singer were the senior scientists on the project. Rosemary Diaz, Anna Marie Nicolaysen, Dugeidy Ortiz and Traci Abraham worked as ethnographic interviewers and were responsible for collecting the data used herein. Traci Abraham drafted the manuscript and was responsible for data interpretation. Mark Macauda provided the quantitative data analysis used in triangulating the qualitative findings as well as quantitative analysis of demographic data. All co-authors, along with Linda Hock-Long, PI from the Philadelphia site, and Marion Carter, Kendra Hatfield-Timajchy and Joan Kraft, all from the CDC, reviewed consecutive drafts of the manuscript and provided critical feedback on its structure and content. This research was supported by Award Numbers U58/CCU123064 and U58/CCU323065 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Division of Reproductive Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Abraham, T., Macauda, M., Erickson, P. et al. “And Let Me See Them Damn Papers!” The Role of STI/AIDS Screening Among Urban African American and Puerto Rican Youth in the Transition to Sex Without a Condom. AIDS Behav 15, 1359–1371 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-010-9811-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-010-9811-z