Abstract

The emerging critique of alternative food networks (AFNs) points to several factors that could impede the participation of low-income, minority communities in the movement, namely, spatial and temporal constraints, and the lack of economic, cultural, and human capital. Based on a semi-experimental study that offers 6 weeks of free produce to 31 low-income African American households located in a New Orleans food desert, this article empirically examines the significance of the impeding factors identified by previous scholarship, through participant surveys before, during, and after the program. Our results suggest economic constraints are more influential in determining where the participants shop for food than spatial and temporal constraints, and the study participants exhibit high levels of human and cultural capital regarding the purchase and consumption of locally grown produce. We also find them undeterred by the market’s predominantly White, middle-class cultural social space, which leads us to question the extent to which cultural exclusivity discourages their participation in AFNs. For all five factors we find that the constraints posed to accessing the local food market were not universal but varied among the participants. Finally, the study reveals some localized social constraints, fragmented social ties in particular, as a possible structural hurdle to engaging these residents in the alternative market in their neighborhood. Conclusions point to the need for a multi-dimensional and dynamic conceptualization of “food access.”

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

This is the actual name of the neighborhood and the organization.

It is important to acknowledge that New Orleans neighborhoods continue to be shaped by gentrification (Gladstone and Préau 2008), repopulation (Elliott et al. 2009; Stringfield 2010), and related neighborhood dynamics (Elliott and Pais 2006; Fussell 2009) in wake of the devastation wrought by Hurricane Katrina. Nevertheless, we do not provide an elaborate discussion of these issues, partly because the food desert status of the neighborhood predates the Hurricane, but also because doing so is out of the scope of the current project. Instead, we refer the reader to the work cited above that explicitly addresses these concerns.

For example, 1 week’s box included the following items: Sweet Potatoes, Apples, Eggplant, Mustard Greens, Pickling Cucumbers, Baby Heirloom Squash, Bell Peppers, Cajun Grain Rice, Red Frill Mustard, Natural Arugula, and Satsumas (October 23, 2013 box delivery content).

Original pre- and post-study surveys, as well as bi-weekly market consumption survey used in the study can be made available upon requests to the authors.

We acknowledge that this only reduced the residents’ barriers to fresh food through the particular market, and not their food purchasing budget in general. The aim was to ease the risk of trying out the new market by providing an economic incentive, which turns out to be roughly equivalent to the average weekly fresh produce budget of our participants (see Table 2).

The expanded business hours impacted only a handful of study participants who started a few weeks behind the others.

HMF’s website and weekly newsletters also feature recipe suggestions, but we used slightly different recipes for our study.

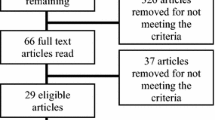

Due to some participants not returning the surveys in a timely manner, we were not able to collect pre-study survey from all of the initially enrolled participants, making our survey data’s total responses per question <31.

We contacted the individuals who ceased to participate to inquire if they would be willing to provide information on why they did not complete the study, but none responded to our multiple attempts at correspondence.

One participant received box deliveries throughout the study due to personal mobility issues that prevented her ability to easily access the store, but this was the only exception in the altering options during the first 4 weeks.

The fact that the majority of the study participants who remained in the study were seniors may contribute to their flexibilities with time, when compared to their younger counterparts.

Abbreviations

- AFN:

-

Alternative food network

- CSA:

-

Community supported agriculture

- EBT:

-

Electronic Benefits Transfer

- HMF:

-

Hollygrove Market and Farm

References

Agyeman, J. 2005. Sustainable communities and the challenge of environmental justice. New York: New York University Press.

Alkon, A.H., and J. Agyeman. 2011. Cultivating food justice: Race, class, and sustainability. Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, England: The MIT Press.

Alkon, A.H., D. Block, K. Moore, C. Gillis, N. DiNuccio, and N. Chavez. 2013. Foodways of the urban poor. Geoforum 48(1): 126–135.

Alkon, A.H., and T.M. Mares. 2012. Food sovereignty in us food movements: Radical visions and neoliberal constraints. Agriculture and Human Values 29(3): 347–359.

Alkon, A.H., and C.G. McCullen. 2011. Whiteness and farmers markets: Performances, perpetuations… contestations? Antipode 43(4): 937–959.

Allen, P. 2008. Mining for justice in the food system: perceptions, practices and possibilities. Agriculture and Human Values 25(2): 157–161.

Allen, P. 2010. Realizing justice in local food systems. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy, and Society 3(2): 295–308.

Allen, P., and J. Guthman. 2006. From “old school” to “farm-to-school”: Neoliberalization from the ground up. Agriculture and Human Values 23(4): 401–415.

Andreatta, S., M. Rhyne, and N. Dery. 2008. Lessons learned from advocating CSAs for low-income and food insecure households. Southern Rural Sociology 23(1): 116–148.

Barnes, S.L. 2003. Determinants of individual neighborhood ties and social resources in poor urban neighborhoods. Sociological Spectrum 21(4): 463–497.

Bedore, M. 2010. Just urban food systems: A new direction for food access and urban social justice. Geography Compass 4(9): 1418–1432.

Bodor, N.J., D. Rose, T.A. Farley, C.M. Swalm, and S.K. Scott. 2007. Neighborhood fruit and vegetable availability and consumption: The role of small food stores in an urban environment. Public Health Nutrition 11(4): 413–420.

Buttel, F.H. 1997. Some observations on agro-food change and the future of agricultural sustainability movement. In Globalising food: Agrarian questions and global restructuring, ed. D. Goodman, and M.J. Watts, 253–268. London, UK: Routledge.

Čapek, S.M. 1993. The “environmental justice” frame: A conceptual discussion and application. Social Problems 40(1): 5–24.

Cummins, S., E. Flint, and S.A. Matthews. 2014. New neighborhood grocery store increased awareness of food access but did not alter dietary habits or obesity. Health Affairs 32(2): 283–291.

DuPuis, E.M., J.L. Harrison, and D. Goodman. 2011. Just food? In Cultivating food justice: Race, class, and sustainability, ed. A.H. Alkon, and J. Agyeman, 283–307. Cambridge, Mass: The MIT Press.

Elliott, J.R., A.B. Hite, and J.A. Devine. 2009. Unequal return: The uneven resettlements of New Orleans’ uptown neighborhoods. Organization & Environment 22(4): 410–421.

Elliott, J.R., and J. Pais. 2006. Race, class, and Hurricane Katrina: Social differences in human responses to disaster. Social Science Research 35(2): 295–321.

Fussell, E. 2009. Social organization of demographic responses to disaster: Studying Population–environment interactions in the case of Hurricane Katrina. Organization & Environment 22(4): 379–394.

Gladstone, D., and J. Préau. 2008. Gentrification in tourist cities: Evidence from New Orleans before and after Hurricane Katrina. Housing Policy Debate 19(1): 137–175.

Goodman, D., and E.M. DuPuis. 2002. Knowing food and growing food: Beyond the production–consumption debate in the sociology of agriculture. Sociologia Ruralis 42(1): 5–22.

Greater New Orleans Community Data Center. 2012. Hollygrove statistical area. http://www.datacenterresearch.org/pre-katrina/orleans/3/12/. Accessed 10 July 2013.

Guthman, J. 2003. Fast food/organic food: Reflexive tastes and the making of ‘yuppie chow’. Social and Cultural Geography 4(1): 45–58.

Guthman, J. 2008a. Bringing good food to others: Investigating the subjects of alternative food practice. Cultural Geographies 15(4): 431–447.

Guthman, J. 2008b. “If they only knew”: Color blindness and universalism in california alternative food institutions. The Professional Geographer 60(3): 387–397.

Hallet IV, L.F., and D. McDermott. 2011. Quantifying the extent and cost of food deserts in Laurence, Kansas, USA. Applied Geography 31: 1210–1215.

Hinrichs, C.C., and K.S. Kremer. 2002. Social inclusion in a Midwest local food system. Journal of Poverty 6(1): 65–90.

Hubley, T.A. 2011. Assessing the proximity of healthy food options and food deserts in a rural area in Maine. Applied Geography 31(4): 1224–1231.

Johnston, J., and L. Baker. 2005. Eating outside the box: FoodShare’s good food box and the challenge of scale. Agriculture and Human Values 22(3): 313–325.

Kato, Y. 2013. Not just the price of food: Challenges of an urban agriculture organization in engaging local residents. Sociological Inquiry 83(3): 369–391.

LeDoux, T.F., and I. Vojnovic. 2013. Going outside the neighborhood: The shopping patterns and adaptations of disadvantaged consumers living in the lower eastside neighborhoods of Detroit, Michigan. Health & Place 19: 1–14.

Lockie, S. 2009. Responsibility and agency within alternative food networks: assembling the “citizen consumer”. Agriculture and Human Values 26(3): 193–201.

Passidomo, C. 2013. Going “beyond food”: Confronting structures of injustice in food systems research and praxis. Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development 3(4): 89–93.

Pearson, T., J. Russell, M.J. Campbell, and M.E. Barker. 2005. Do ‘food deserts’ influence fruit and vegetable consumption?—a cross-sectional study. Appetite 45(2): 195–197.

Rose, D.J., N. Bodor, C.M. Swalm, J.C. Rice, T.A. Farley, and P.L. Hutchinson. 2009. Deserts in New Orleans?: Illustrations of urban food access and implications for policy. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan National Poverty Center/USDA Economic Research Service Research.

Russell, S.E., and C.P. Heidkamp. 2011. ‘Food desertification’: The loss of a major supermarket in New Haven, Connecticut. Applied Geography 31(4): 1197–1209.

Shaw, H.J. 2006. Food deserts: Toward the development of a classification. Geofgrafiska Annaler. Series B. Human Geography 88(2): 231–247.

Short, A., J. Guthman, and S. Raskin. 2007. Food deserts, oases, or mirages?: Small markets and community food security in the San Francisco Bay Area. Journal of Planning Education and Research 26(3): 352–364.

Slocum, R. 2007. Whiteness, space, and alternative food practice. Geoforum 38(3): 520–533.

Slocum, R. 2008. Thinking race through corporeal feminist theory: Divisions and intimacies at the Minneapolis Famers’ Market. Social and Cultural Geography 9(8): 849–869.

Stringfield, J.D. 2010. Higher ground: an exploratory analysis of characteristics affecting returning populations after Hurricane Katrina. Population and Environment 31(1–3): 43–63.

Thomas, B.J. 2010. Food deserts and the sociology of space: Distance to food retailers and food insecurity in an urban american neighborhood. International Journal of Human and Social Sciences 5(6): 400–409.

USDA Economic Research Service. 2013. Food access research atlas: documentation. http://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/food-access-research-atlas/documentation.aspx#.UioUS7yE4so. Accessed 6 Sept 2013.

Weisman, J., and R. Nixon. 2013. House republicans push through farm bill, without food stamps. July 11, 2013. New York: The New York Times.

Whelan, A., N. Wrigley, D. Warm, and E. Cannings. 2002. Life in a ‘food desert’. Urban Studies 39(11): 2083–2100.

Widener, M.J., S.S. Metcalf, and Y. Bar-Yam. 2011. Dynamic urban food environments: A temporal analysis of access to healthy foods. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 41(4): 439–441.

Wrigley, N. 2002. ‘Food deserts’ in british cities: Policy context and research priorities. Urban Studies 39(11): 2029–2040.

Young, C., A. Karpyn, N. Uy, K. Wich, and J. Glyn. 2011. Farmers’ markets in low income communities: impact of community environment, food programs and public policy. Community Development 42(2): 208–220.

Acknowledgments

Authors thank Melissa Moss, Sarah Denson, Sarah Sklaw, Tyler Minick, Jennifer Mirman, who assisted in conducting the free produce program in Hollygrove neighborhood, as well as Hollygrove Market and Farm for collaborating with us on the project. We thank the editor and the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and suggestions for improving the manuscript. We also thank the Center for Public Service at Tulane University for providing funding for the project through the Community-based Research Program grant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kato, Y., McKinney, L. Bringing food desert residents to an alternative food market: a semi-experimental study of impediments to food access. Agric Hum Values 32, 215–227 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-014-9541-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-014-9541-3