Abstract

Aedes aegypti is implicated in dengue transmission in tropical and subtropical urban areas around the world. Ae. aegypti populations are controlled through integrative vector management. However, the efficacy of vector control may be undermined by the presence of alternative, competent species. In Puerto Rico, a native mosquito, Ae. mediovittatus, is a competent dengue vector in laboratory settings and spatially overlaps with Ae. aegypti. It has been proposed that Ae. mediovittatus may act as a dengue reservoir during inter-epidemic periods, perpetuating endemic dengue transmission in rural Puerto Rico. Dengue transmission dynamics may therefore be influenced by the spatial overlap of Ae. mediovittatus, Ae. aegypti, dengue viruses, and humans. We take a landscape epidemiology approach to examine the association between landscape composition and configuration and the distribution of each of these Aedes species and their co-occurrence. We used remotely sensed imagery from a newly launched satellite to map landscape features at very high spatial resolution. We found that the distribution of Ae. aegypti is positively predicted by urban density and by the number of tree patches, Ae. mediovittatus is positively predicted by the number of tree patches, but negatively predicted by large contiguous urban areas, and both species are predicted by urban density and the number of tree patches. This analysis provides evidence that landscape composition and configuration is a surrogate for mosquito community composition, and suggests that mapping landscape structure can be used to inform vector control efforts as well as to inform urban planning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Dengue is a vector-borne virus transmitted by the bites of infected mosquitoes, mainly Aedes aegypti (Hotez et al. 2008; Kyle and Harris 2008; WHO 2009). It is an acute febrile disease causing 50–100 million cases per year and for which more than 2.5 billion people are at risk (WHO 2009). Dengue incidence increased 30-fold in the last 50 years (CDC 2009), coinciding with rapid urbanization. Given the close link of the vector to urban areas (WHO 2009), dengue incidence is expected to rise with increasing urban population, especially in developing countries where urban growth outpaces government’s capacity to provide infrastructure (Barrera et al. 1993, 1995; Troyo et al. 2009).

Individuals who acquire dengue develop immunity to the infecting serotype, but subsequent infection with a different serotype can lead to the more severe forms of dengue, including dengue hemorrhagic fever and dengue shock syndrome (Kendall et al. 2009). Due to this complication of multiple viral serotypes and immunological responses to sequential coinfection, there is currently no vaccine for dengue (CDC 2009); however, a tetravalent vaccine is currently in clinical trials (Morrison et al. 2010). With or without a vaccine, best practices for dengue prevention are integrated vector control methods including reduction of vector-producing containers and community education and participation (Gubler 2006). Sustaining community participation strategies in inter-epidemic years is difficult, though integral to the success of these programs (Lloyd 2003). By identifying areas of high dengue transmission risk, resources can be focused to the areas of greatest need (Wilson 2002).

Aedes aegypti lives in close association with humans and preferentially bites human hosts (Harrington et al. 2001; Kyle and Harris 2008; CDC 2009). Given its key role on the emergence of epidemic dengue in urban areas, vector control methods have focused on controlling Ae. aegypti by elimination of domestic and peridomestic water-filled artificial containers that produce mosquitoes. However, the efficacy of vector control methods may be limited by the presence of alternate invasive or native container-breeding species. In Puerto Rico, Ae. mediovittatus may be implicated in the transmission of dengue based on the laboratory observations that it feeds on humans, has greater vector competence and rates of vertical transmission of dengue viruses than Ae. aegypti (Gubler et al. 1985; Freier and Rosen 1988). Aedes mediovittatus is a native tree hole mosquito and is closely associated with arboreal vegetation (Cox et al. 2007). It has been proposed that Ae. mediovittatus can act as a reservoir in the maintenance of dengue viruses during inter-epidemic periods in rural areas with low human population density (Gubler et al. 1985). Areas where Ae. aegypti and Ae. mediovittatus co-occur may be at higher risk for dengue persistence between epidemics. The rationale is that: (1) during epidemics, high virus amplification by Ae. aegypti would increase the likelihood of Ae. mediovittatus becoming infected; (2) dengue viruses would persist in these areas during inter-epidemic periods due to the high rate of vertical transmission observed in Ae. mediovittatus in the laboratory; and (3) dengue transmission by Ae. mediovittatus to humans and Ae. aegypti in areas of overlap could catalyze another epidemic. While targeting areas of high Ae. aegypti production is important during epidemic periods, habitats of high Ae. mediovittatus production may be better targets during inter-epidemic periods. Our aim in this study is to develop a predictive model of areas where both Aedes species overlap to conduct intensive sampling of Ae. mediovittatus and assess infection with DENV. Moreover, identifying the areas where these two species overlap is critical to focus interventions to curb future dengue epidemics.

The spatial overlap of adult Ae mediovittatus, Ae. aegypti, dengue viruses, and humans in Puerto Rico has not been determined (Cox et al. 2007). In Puerto Rico, immature Ae. aegypti have been shown to occur close to houses (99%) while Ae. mediovittatus were more likely to occur far from houses (Moore 1983). In San Juan, Puerto Rico, immature Ae. aegypti and Ae. mediovittatus were found to segregate across an urban gradient (Cox et al. 2007) with Ae. aegypti found in areas with higher housing density (Smith et al. 2009). However, Ae. mediovittatus was found in containers within San Juan, particularly in areas of lower density housing and forested areas (Cox et al. 2007; Smith et al. 2009) and at the peak of the rainy season when most dengue viral disease transmission occurs (Smith et al. 2009). Ae. mediovittatus requires high humidity to survive as an adult (Cox et al. 2007) which may explain why it prefers vegetated areas.

Research utilizing remote sensing for the study of dengue has been limited (Eisen and Lozano-Fuentes 2009). There are four proposed explanations for the limited use of mapping, including remote sensing, for the study of dengue risk: (1) traps for adult Ae. aegypti had not been efficacious and emphasis has been placed on sampling immatures (Eisen and Lozano-Fuentes 2009); (2) dengue researchers have focused on the importance of small containers to determine the risk of dengue, precluding the utility of remote sensing which has not been shown to be able to discern containers at the fine scale needed (Moloney et al. 1998; Eisen and Lozano-Fuentes 2009); (3) environmental characteristics such as the normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) may only be relevant in locations where containers are rain filled and trees prevent evapotranspiration rather than filled and maintained by humans (Eisen and Lozano-Fuentes 2009); and (4) the risk of dengue outbreaks is influenced not only by the abundance of mosquitoes but also the serotype specific herd immunity of the population (Eisen and Lozano-Fuentes 2009).

These concerns have resulted in a focus on epidemiological approaches rather than entomological or ecological. There are, however, exceptions. Remote sensing has been used to map landscape features such as tidiness and shade levels of backyards as predictors of suitable Ae. aegypti breeding habitats (Tun-Lin et al. 1995; Moloney et al. 1998) and to map environmental conditions, temperature, and precipitation, using NDVI as a proxy for precipitation (Estallo et al. 2008). Remote sensing has also been used to map dengue transmission risk by mapping land use change in Thailand (Vanwambeke et al. 2007) and landscape structure in Hawaii (Vanwambeke et al. 2011). Still there are few studies using remote sensing at high spatial resolution to assess Ae. aegypti habitat in urban areas (Troyo et al. 2009).

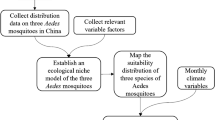

Here we used high resolution remote sensing to map elements of urban structure, tree cover and built-up areas, to predict Ae. aegypti within urban areas as has been done in previous studies (Troyo et al. 2008; Fuller et al. 2010). The goal of this research is to determine environmental features associated with high abundance of Ae. aegypti and Ae. mediovittatus at different spatial scales and identify and map the environmental conditions that result in high levels of co-occurrence. Since immature mosquitoes have been shown to segregate along an urbanization gradient (Cox et al. 2007), we hypothesize that Ae. aegypti will be more closely associated with urban areas while Ae. mediovittatus will be more likely to be found in forested areas. We used novel BG-sentinel traps previously shown to be efficacious at collecting adult Aedes spp. mosquitoes (Kroeckel et al. 2006; Maciel de Freitas et al. 2006; Williams et al. 2006) and data from a newly launched satellite of high spatial and spectral resolution to characterize features of the urban environment predictive of habitat segregation of the two Aedes species. Mapping areas of co-occurrence will identify areas that will be used to refine a trapping scheme aimed at determining the role of Ae. mediovittatus in the transmission dynamics of dengue in Puerto Rico.

Methods

Mosquito Collection

The study was conducted from May to August 2010 in the municipality of Patillas in South-Eastern Puerto Rico. The selection of Patillas as a study site is based on the availability of preliminary data indicating the presence of both Ae. aegypti and Ae. mediovittatus. Dengue is endemic in Puerto Rico, all four serotypes have been involved with epidemics occurring every 2–3 years since before 1985 (Gubler et al. 1985) and surveillance in Patillas has shown that dengue is endemic to this area (CDC, unpublished).

Sampling was conducted in nine study sites, representing the highest density of urban development at three different altitude levels in Patillas, however, because of the presence of cloud cover in the satellite image over two of the sites, we report our findings only for seven of the study areas (Fig. 1). 90 BG-Sentinel traps were used to capture adult mosquitoes in the rainy season, between May and August 2010. Mosquito collection ran for 3 days: the traps were set on Monday with collection Tuesday through Thursday. A second sampling round was completed for each BG location at each study site 1 month later. All traps were baited with BG-Lure®, which contains non-toxic substances specifically found on human skin including ammonia, lactic acid, and fatty acids (Bhalala and Arias 2009). BG-Sentinel traps are highly effective at collecting host seeking adult mosquitoes especially Ae. aegypti (Kroeckel et al. 2006; Williams et al. 2006; Williams et al. 2007). A study in Brazil comparing BG-Sentinel traps to CDC backpack aspirators found that BG-Sentinel traps collected significantly more Ae. aegypti adult male and female mosquitoes than CDC aspirators (Maciel de Freitas et al. 2006). Trap sites were selected by locating one house per 100 m2 sampling grid. The distance between sampling sites is based only on the flight range of Ae. aegypti (Reiter et al. 1995; Honorio et al. 2003) because the flight range of Ae. mediovittatus remains unknown. Trap placement was restricted to areas in close proximity to buildings to only include areas that were inhabited and where dengue transmission was likely to occur.

Land Cover/Land Use Classification and Characterization of Landscape Patterns

We used data acquired by the WorldView2 satellite sensor, launched on October 8, 2009. A WorldView2 scene was acquired on 25 March 2010. WorldView2’s features include high spatial resolution of 1.82 m (2 m output pixels) and 8-band spectral resolution. The high spatial resolution provided by WorldView2 is important for analyzing the fine-scale environmental drivers of these mosquito species, 8 bands provide higher ability to discriminate among features than the 4 bands available for other high resolution sensors.

We collected ground-based site-specific information on land cover types around BG-Sentinel traps by annotating printed satellite images. ‘Regions of interest’ composed of individual pixels were manually entered into ENVI, Environment for Visualizing Images (ITT 2011) for supervised classification training and testing. Seventy-five percent of pixels were used for training and 25% for testing the classification. Of the nine original study sites, two, Jagual and Pueblo, were occluded by clouds and excluded from the study. The remaining seven study sites were classified individually using an iterative approach. The first step was to mask out shadows, defined as those pixels with the lower 10% value for the WorldView2’s blue band digital number (DN). Secondly, an urban mask was defined by an upper bound of NDVI equal to 0.4, to include the diverse urban structures in Patillas. Finally, a maximum-likelihood algorithm was used to perform a supervised classification of vegetation into four categories: bare soil, grass, scrub, and trees. Bare soil was defined as exposed soil in urban areas and very sparsely vegetated areas. The grass category was low vegetation. The scrub category was primarily deforested areas that have thick regenerated cover but lack tall vegetation (trees). The tree category included single trees as well as forested areas.

Landscape metrics were derived from the above classification using a combination of programs: ArcMap (ESRI 2011), Geospatial Modeling Environment (GME) (Beyer 2011), and FRAGSTATS (McGarigal et al. 2002). GME was used to clip the classified image into the areas around each trapping location (the ‘landscape patch’) at three spatial scales (25, 50, and 100 m) around each BG trap and then FRAGSTATS was used to calculate landscape metrics at those scales. The 25 m landscape patches represent the house-specific environmental factors. The larger landscape patches characterize environmental factors operating at larger spatial scales, such as the presence of a larger forested area. For each landscape patch, the total number of patches of each class, the class area distribution statistics, and a cohesion metric were calculated using FRAGSTATS for the two focal classes (forest and urban). The number of patches is a simple measure of the extent of fragmentation of the class-patch type; the class-patch area distribution metrics quantify the level of fragmentation for each focal class. Finally, the cohesion metric for the two main focal classes, forest and urban, characterize the configuration of the class-patches.

where P is the class-patch perimeter, a is the class-patch area, and A is the total number of cells in the landscape patch (McGarigal et al. 2002). Cohesion is a percentage ranging in values from 0 to 100. As the value approaches zero the proportion of the landscape patch comprised with the focal class-patch decreases and becomes increasingly subdivided and less connected (McGarigal et al. 2002).

Housing density was derived from a digitized point shapefile of all structures in Patillas, Puerto Rico, derived from the Internal Revenue Agency of Puerto Rico. These points were subjected to kernel density estimation using the spatial analyst toolbox of ArcMap. To calculate the mean density at each spatial scale, ArcMap zonal statistics tool was used.

Weather Data

To account for temporal changes in weather parameters between samplings and to examine the response of each mosquito species to these variables, we operated three weather stations at three elevations (Jagual, Recio, and Quebrada Arriba) (Hobo Micro Station; Onset Computer, Bourne, MA). Rainfall is an important factor because its accumulation is necessary for larval development of mosquitoes. At each mosquito collection observation, the accumulated rainfall during weeks 3 and 2 before sampling was recorded. The week prior to sampling is omitted because immature development lasts 7 days and so this rainfall does not contribute to the number of adult mosquitoes. Seasonal patterns related to temperature and rainfall are reflected in the breeding patterns of the vectors and dispersal of dengue (Moore et al. 1978; Honorio et al. 2009; Kyle and Harris 2008).

Statistical Analyses

Population-averaged panel-data models (xtgee procedure) were run in STATA (StataCorp 2007) to model the association of mosquito counts or presence/absence and environmental parameters. Generalized estimating equations (GEE) are widely used in the analysis of longitudinal data in epidemiologic studies (Cui 2007) and spatially explicit data in ecological studies (Kraan et al. 2010). The xtgee procedure is suited to fit generalized linear models when there is within-group correlation structure for the panels (StataCorp 2011). To account for the possibility of temporal and/or spatial within-group correlation we specified both the location of the BG-Sentinel traps as well as the date of trapping. GEE are based on quasi-likelihood theory, therefore traditionally used Akaike’s information criterion (AIC) cannot be used to compare models (Pan 2001). Pan (2001) proposed an alternative method called the Quasi-likelihood under Independence model Criterion (QIC), which can be used to determine the best set of covariates to explain an outcome (Pan 2001; Cui 2007).

We used a GEE model with binomial family, logit link, two panel variables location and date, and an independent correlation structure to assess the landscape features predictive of the distribution of Ae. aegypti and Ae. mediovittatus and those that are predictive of co-occurrence. We calculated two-category variables for Ae. aegypti and Ae. mediovittatus splitting the distribution of Ae. aegypti at the mean to create a high/low variable and splitting the distribution of Ae. mediovittatus to presence/absence. We assessed the predictive value of individual variables through a univariate analysis using QIC values. To avoid including collinear variables in the model, correlated variables (P < 0.01) were compared in the univariate analysis and the variable with higher QIC was excluded from the final model. To determine the influence of scale, we ran models with the best set of covariates at each scale as well as a mixed scale model using the best set of covariates across all three scales. We used QIC to determine the models with the best set of covariates to explain the outcomes of interest: presence of high numbers of Ae. aegypti compared to low numbers; presence of Ae. mediovittatus compared to absence; and co-occurrence of high numbers of Ae. aegypti; and presence of Ae. mediovittatus. We calculated Moran’s I spatial autocorrelation statistics based on the regression residuals to determine if the covariates explained all of the model’s variation.

Predictive Map

The final predictive model was then mapped using ArcMap to determine risk of co-occurrence across the study area. We generated raster grids for the predictive variables. Using the spatial analyst tool raster calculator we then ran the regression equation for each pixel resulting in a risk map of co-occurrence throughout the study area with resolution of 2 m.

Results

We obtained 1,260 mosquito collections from 235 trapping sites, with an average of 5.4 collections per trap site (range 2–6). Over the entire sampling period we collected 7,057 males and 8,787 females (0.8♂:1♀) of Ae. aegypti and 92 males and 1,090 females (0.08♂:1♀) of Ae. mediovittatus. Average numbers of Ae. aegypti adults per trap per day were higher than those of Ae. mediovittatus in most study sites, with the exception of Mulas (Table 1). The two localities with the highest densities of Ae. aegypti per trap, such as Lamboglia and Quebrada Arriba also showed the highest densities of Ae. mediovittatus (Table 1). The percentages of traps with both species (co-occurrence) also were the highest in Lamboglia and Quebrada Arriba (Table 1). Co-occurrence was minimal in the two localities with the lowest densities (Mamey and Mulas). These areas received the lowest levels of rainfall that were observed during the field study (Table 1). Other mosquito species collected in BG traps during the study were Aedes taeniorhynchus, Ae. tortilis, Culex bahamensis, Cx. quinquefasciatus, Cx.antillummagnorum, and Toxorhynchites portoricensis.

Satellite image classification accuracy ranged from 80 to 99% with associated kappa coefficients of 0.73 to 0.9 (Fig. 1). For all three outcomes (presence of high numbers of Ae. aegypti compared to low numbers, presence of Ae. mediovittatus compared to absence, and co-occurrence of high numbers of Ae aegypti and presence of Ae. mediovittatus), we found that mixed scale models had the best predictive values, indicated by lowest QIC scores (Table 2). For Ae. aegypti, the model with the best fit included the covariates number of tree patches within 50 m, housing density within 25 m, rainfall, and temperature and was statistically significant (χ2 = 273, df = 5, P < 0.001). For Ae. mediovittatus, the final model included number of tree patches within 100 m, urban patch area within 50 m, rainfall, and temperature and was statistically significant (χ2 = 62, df = 5, P < 0.001), The overall model predicting co-occurrence (statistically significant (χ2 = 137, df = 5, P < 0.001)) included the covariates housing density within 25 m, the number of tree patches within 100 m, and rainfall.

We used Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) to plot the true positive rate (sensitivity) as a function of one minus the false positive rate (specificity) (STATA SE 10 2007). The model predicting Ae. aegypti results in an AUC value of 0.83, suggesting that a random sample of positive observations has a test value larger than that of negative observations 83% of the time (mediovittatus 64% of the time; co-occurrence 75% of the time). Moran’s I statistic based on the regression residuals was not significant in five of the seven study sites, and significant for two, indicating some residual spatial structure not explained by the covariates specified.

To create an ecological risk map of co-occurrence across the study area we used the logistic regression model predicting co-occurrence. To create the raster grid for house density we calculated the kernel density at 25 m throughout the entire study area. To extract values of the number of tree patches over the entire study area we overlaid a 50 m × 50 m grid and calculated the number of tree patches in each grid cell. The map depicting risk of co-occurrence illustrates the heterogeneity across the landscape within the inhabited areas of Patillas, Puerto Rico (Fig. 2). The communities Lamboglia and Providencia show the greatest risk for co-occurrence of Ae. aegypti and Ae. mediovittatus. These are areas of higher urban density but also have a high number of tree patches.

Discussion

In this study, we identified density of urban and vegetation structure as important habitat features for Ae. aegypti and Ae. mediovittatus abundance and for their co-occurrence. The analysis of high resolution remotely sensed data enabled us to look at the scale at which the landscape metrics had the most influence on predicting mosquito distribution. Ae. aegypti is positively predicted by urban density but also by the number of tree patches. The scale at which these covariates predict Ae. aegypti distribution are localized to the immediate (25 m) urban environment and to an intermediate scale (50 m) for the influence of trees. Ae. mediovittatus is negatively predicted by the large urban areas at an intermediate scale (50 m) and positively predicted by the number of tree patches at a larger spatial scale of 100 m. The models suggest that Ae. aegypti may be more influenced by local environmental features, while Ae. mediovittatus may be more influenced by landscape structure at a coarser scale. The use of a model considering multiple scales simultaneously indicates the importance of landscape structure and composition at different spatial scales. However, the three scales analyzed are all relatively local. Further research should incorporate the influence of landscape structure and composition at a larger geographical scale.

The models showed significant positive associations of each mosquito species with accumulated rainfall (2–3 weeks before sampling) that must have resulted from an increased number of water-filled containers. Temperature was positively associated with high Ae. aegypti and negatively associated with presence of Ae. mediovittatus. This difference is likely associated with the main types of terrestrial habitats occupied by these species. For example, Ae. mediovittatus is more prevalent in areas with tall vegetation where air temperature should be lower than in built-up areas where Ae. aegypti is more abundant. Rainfall and temperature are important drivers of the population dynamics of Ae. aegypti (Moore et al. 1978) and, arguably more so, for Ae. mediovittatus (Gubler et al. 2001; Smith et al. 2009) as well as dengue in Puerto Rico (Johansson et al. 2009).

Overall the results of the model support previous findings about the habitat preferences of immature Ae. aegypti and Ae. mediovittatus, with Ae. aegypti preferring containers located in high density urban areas, Ae. mediovittatus preferring lower density urban areas and both Aedes species overlapping in urban areas with high canopy cover (Cox et al. 2007). We determined that the same variables are associated with co-occurrence of adults. Previous studies on the influence of landscape structure on Aedes spp. distribution and abundance, habitat preferences, and community structure are limited (Rey et al., 2006). Heterogeneities of urban/built up structure have been linked to Ae. aegypti distribution (Troyo et al. 2009). Recent research on Ae. albopictus in Hawaii specifically investigated vegetation and urban structure using landscape metrics (Vanwambeke et al. 2011). Vanwambeke et al. (2011) incorporated residential density data, recreational areas, mosquito abundance, and environmental factors to identify areas with abundant mosquitoes and where humans actively visit to pinpoint areas of high transmission risk. They found that the areas with highest abundance of Ae. albopictus were in a mixture of urban/built up and vegetated areas (Vanwambeke et al. 2011). This result is remarkably similar to our findings for Ae. mediovittatus. Ae. mediovittatus has been likened to Ae. albopictus, “the albopictus of the Caribbean”, due to similar habitat requirements (Gubler et al. 1985). Understanding the habitat preferences of Ae. aegypti and Ae. mediovittatus should guide research of habitat preferences and community structure of Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus.

The biotic interactions between larvae of Ae. aegypti and Ae. mediovittatus have not yet been investigated. Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus overlap during immature development in containers and when natural (leaf litter) resources are limited Ae. albopictus outcompetes Ae. aegypti (Barrera 1996). Research on land use change in Thailand found Ae. aegypti was limited to artificial containers in settled areas while Ae. albopictus was in artificial and natural containers in both settled and agricultural areas (orchards) (Vanwambeke et al. 2007). Ae. aegypti adaptation to urban life and increased dengue transmission in densely populated areas are cited as the main reasons for the emergence of dengue as a public health problem in the last 50 years (WHO 2009). Rapid urbanization that outpaces governmental capacity to maintain housing standards and provide reliable access to drinking water, trash collection, and excreta disposal are main drivers for dengue fever emergence (Barrera et al. 1993; Barrera et al. 1995; Troyo et al. 2009). Ae. aegypti is well adapted to crowded tropical cities, but has also been found in other urban habitats (Cox et al. 2007). Troyo et al. (Troyo et al. 2009) developed a model including tree cover and built-up areas and found that moderately built up residential areas with moderate tree cover were likely to have high numbers of habitats suitable for Ae. aegypti larvae and that an important portion of habitats containing mosquito larvae were not near houses. A study in Brazil found that Ae. aegypti oviposition was related to the urbanization gradient, indicating preference for certain resources at the rural urban interface (Carbajo et al. 2006). And, in Australia an increase in shade in backyards was linked to increased risk of immature Ae. aegypti (Tun-Lin et al. 1995). Ae. aegypti exploits a wide range of containers as developmental habitats from discarded rain-filled containers to anthropogenic water storage containers (Barrera et al. 2006; Kendall et al. 2009). Previous observations in Puerto Rico suggest that most containers with water suitable for mosquito development are outdoors (Moore et al. 1978) and in unattended rain-filled containers (Barrera et al. 2006). Containers filled with water and organic matter or under trees were found to produce the largest adult Ae. aegypti, which has faster development and better survival rates (Tun-Lin et al. 2000). Tree canopies may provide benefits to larvae by reducing evapotranspiration and adding nutritious leaf detritus in rain filled containers (Barrera et al. 2006). Urban areas with high canopy cover may therefore be important targets for Aedes spp. vector control efforts.

The metrics developed in this study to map areas of co-occurrence will be employed to refine a trapping schedule aimed at determining the role of Ae. mediovittatus in the transmission dynamics of dengue in Puerto Rico. We speculate that in areas of co-occurrence Ae. mediovittatus will be more likely to carry dengue then in areas where it does not overlap with Ae. aegypti. However, this study is limited by the exclusion of human movement and human interaction with the environment as mechanisms of dengue transmission. Human movement is thought to be an important driver of dengue transmission and targeting key individuals and areas frequented by large numbers of people may improve disease prevention (Stoddard et al. 2009). Because Ae. mediovittatus prefers more forested areas it is possible that human movement between urban and rural areas facilitates transmission of dengue. If Ae. mediovittatus is incriminated as a competent dengue vector in the wild, future research should investigate where humans and Ae. mediovittatus come into contact.

Mapping areas of co-occurrence also has relevance to urban planning. The habitat of co-occurrence with a mix of urban and tree patches could be described as low-density development patterns that cut into forested areas. If Ae. mediovittatus is incriminated as a reservoir for dengue during inter-epidemic periods then areas of co-occurrence may be at higher risk for dengue emergence. If Ae. mediovittatus is involved in dengue transmission then it should be the object of vector control wherever it overlaps with humans.

The results also suggest that in rural areas like Patillas the intermixing of urban areas with tree patches positively predicts Ae. aegypti and reducing this type of development pattern may be important for reducing dengue transmission. The landscape of Puerto Rico is undergoing rapid transformation due to both urban expansion and forest recovery; Puerto Rico underwent conversion from an agricultural to an industrial economy 60 years ago (Martinuzzi et al. 2007). A total of 11% of the island is urban surfaces and a large portion of this development occurs in low-density patterns. Like other mountainous islands, urban areas are concentrated to the coasts and valleys, however, in Puerto Rico much of the low-density development occurs at the forest–urban interface (Martinuzzi et al. 2007). Land use change mediated by humans is linked to many vector-borne diseases (Patz et al. 2004) through the creation of new habitats, the expanding range of vectors, and changing mosquito community structure (Vanwambeke et al. 2007). Vanwambeke et al. (2007) challenge the theory that intact forest ecosystems regulate pathogens and disease, and suggest that some ecosystem services are actually “disservices” that create new nodes of disease transmission. In the case of Patillas, Puerto Rico the intermixing of urban with tree patches may result in such an ecosystem “disservice.” Puerto Rico is a “window to the future” for Caribbean islands because many Caribbean islands are only now making the transition from an agricultural economy (Martinuzzi et al. 2007). Informed urban planning that provides public infrastructure and minimizes sprawl through zoning initiatives such as urban growth boundaries may significantly reduce dengue transmission in Puerto Rico and provide a model for other Caribbean islands.

In conclusion, this research highlights the importance of landscape structure and composition for predicting Aedes mosquitoes and risk of dengue transmission. The use of high resolution remote sensing is key to determine the structure and composition of the landscape at a local scale. The use of high resolution or potentially medium-resolution remote sensing could be used to look at larger scale landscape patterns that influence the distribution of Ae. aegypti and Ae. mediovittatus. Further research should aim to clarify the occurrence and persistence of dengue in Ae. mediovittatus around areas of co-occurrence with Ae. aegypti. A landscape ecology approach contributes to our understanding of vector biology by adding the importance of landscape pattern to what has been previously elucidated about land cover types predictive of mosquitoes (e.g., NDVI). The importance of landscape pattern contributes to our understanding of vector control. Localized vector control efforts may fail if they do not consider the importance of urban development patterns. Future research should directly address how urban development patterns influence dengue epidemiology.

References

Barrera R (1996). Competition and resistance to starvation in larvae of container-inhabiting Aedes mosquitoes. Ecological Entomology 21:117-127.

Barrera R, Avila J, and Gonzaleztellez S (1993). Unreliable Supply of Potable Water and Elevated Aedes aegypti Larval Indexes - A Causal Relationship. Journal of the American Mosquito Control Association 9:189-195.

Barrera R, Navarro JC, Mora JD, Dominguez D, and Gonzalez J (1995). Public service deficiencies and Aedes aegypti breeding sites in Venezuela. Bulletin of the Pan American Health Organization 29:193-205.

Barrera R, Amador M, and Clark GG (2006). Use of the pupal survey technique for measuring Aedes aegypti (Diptera : Culicidae) productivity in Puerto Rico. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 74:290-302.

Beyer H (2011) Geospatial Modelling Environment, Spatial Ecology LLC. www.spatialecology.com

Bhalala H, Arias JR (2009) The Zumba mosquito trap and BG-Sentinel trap: novel surveillance tools for host-seeking mosquitoes. Journal of the American Mosquito Control Association 25(2):134-139.

Carbajo AE, Curto SI, and Schweigmann NJ (2006). Spatial Distribution pattern of oviposition in the mosquio Aedes aegypti in relation to urbanization in Buenos Aires: southern fringe bionomics of an introduced vector. Medical and Veterinary Entomology 20:209-218.

CDC (2009) Prevention, CDC. Dengue: Entomology and Ecology. http://www.cdc.gov/dengue/entomologyEcology/index.html. Accessed September 15, 2010

Cox J, Grillet ME, Ramos OM, Amador M, and Barrera R (2007). Habitat segregation of dengue vectors along an urban environmental gradient. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygeine 76:820-826.

Cui J (2007). QIC program and model selection in GEE analyses. Stata Journal 7:209-220.

Eisen L, and Lozano-Fuentes S (2009) Use of mapping and spatial and space-time modeling approaches in operational control of Aedes aegypti and dengue. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 3:e411.

ESRI (2011). ArcMap 10. Redlands, CA: ESRI (Environmental Systems Resource Institute).

Estallo EL, Lamfri MA, Scavuzzo CM, Almeida FFL, Introini MV, Zaidenberg M, et al. (2008). Models for predicting Aedes aegypti larval indices based on satellite images and climatic variables. Journal of the American Mosquito Control Association 24:368-376.

Freier JE, and Rosen L (1988). Vertical transmission of dengue viruses by Aedes mediovittatus. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygeine 39:218-222.

Fuller DO, Troyo A, Calderon-Arguedas O, and Beier JC (2010). Dengue vector (Aedes aegypti) larval habitats in an urban environment of Costa Rica analysed with ASTER and QuickBird imagery. International Journal of Remote Sensing 31:3-11.

Gubler DJ (2006). Dengue/dengue haemorrhagic fever: history and current status. Novartis Found Symp 277:3-16; discussion 16-22, 71-13, 251-253.

Gubler DJ, Novak RJ, Vergne E, Colon NA, Velez M, and Fowler J (1985). Aedes (Gymnometopa) mediovittatus (Diptera: Culicidae), a potential maintenance vector of dengue viruses in Puerto Rico. Journal of Medical Entomology 22:469-475.

Gubler DJ, Reiter P, Ebi KL, Yap W, Nasci R, Patz J (2001) Climate variability and change in the United States: potential impacts and rodent-borne diseases. Environmental Health Perspectives 109(2):211–221

Harrington LC, Edman JD, and Scott TW (2001). Why do female Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) feed preferentially and frequently on human blood? Journal of Medical Entomology 38:411-422.

Honorio NA, Silva WD, Leite PJ, Goncalves JM, Lounibos LP, and Lourenco-de-Oliveira R (2003). Dispersal of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus (Diptera : Culicidae) in an urban endemic dengue area in the State of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Memorias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz 98:191-198.

Honorio NA, Codeco CT, Alvis FC, Magalhaes M, and Lourenco-De-Oliveira R (2009). Temporal Distribution of Aedes aegypti in Different Districts of Rio De Janeiro, Brazil, Measured by Two Types of Traps. Journal of Medical Entomology 46:1001-1014.

Hotez PJ, Bottazzi ME, Franco-Paredes C, Ault SK, Periago MR (2008) The neglected tropical diseases of Latin America and the Caribbean: a review of disease burden and distribution and a roadmap for control and elimination. Plos Neglected Tropical Diseases 2:e300.

ITT Visual Information Solutions (2011). ENVI Environment for Visualizing Images. ITT, Boulder, Colorado.

Johansson MA, Dominici F, and Glass GE (2009). Local and global effects of climate on dengue transmission in puerto rico. PLoS Neglicted Tropical Diseases 3:e382.

Kendall C, Hudelson P, Leontsini E, Winch P, and Lloyd L (2009). Urbanization, Dengue, and the Health Transittion - Anthrpological Contributions to International health. Medical Anthropology Quarterly 5:257-268.

Kraan C, Aarts G, van der Meer J, and Piersma T (2010). The role of environmental variables in structuring landscape-scale species distributions in seafloor habitats. Ecology 91:1583-1590.

Kroeckel UA, Rose A, Eiras AE, Geier M (2006). New tools for surveillance of adult yellow fever mosquitoes: Comparison of trap catches with human landing rates in an urban environmnet. Journal of the American Mosquito Control Association. 22: 229-238.

Kyle JL, and Harris E (2008). Global Spread and Persistence of Dengue. Annual Review of Microbiology 62:71-92.

Lloyd L (2003). Best Practices for dengue prevention and control in the Americas. USAID, Washington, DC.

Maciel de Frietas R, Eiras AE, Lourenço-de-Oliveira R (2006). Field Evalution of effectiveness of the BG-Sentinal, a new trap for capturing adult Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culcidae). Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz 101(3): 321-325.

Martinuzzi S, Gould WA, and Gonzalez OMR (2007). Land development, land use, and urban sprawl in Puerto Rico integrating remote sensing and population census data. Landscape and Urban Planning 79:288-297.

McGarigal K, Cushman SA, Neel MC, Ene E (2002) FRAGSTATS: Spatial Pattern Analysis Program for Categorical Maps. http://www.umass.edu/landeco/research/fragstats/fragstats.html. Accessed January 1, 2011

Moloney JM, Skelly C, Weinstein P, Maguire M, and Ritchie S (1998). Domestic Aedes aegypti breeding site surveillance: Limitations of remote sensing as a predictive surveillance tool. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 59:261-264.

Moore CG (1983). Habitat Differences among Container-Breeding Mosquitos in Western Puerto-Rico (Diptera, Culicidae). Pan-Pacific Entomologist 59:218-228.

Moore CG, Cline BL, Ruiztiben E, Lee D, Romneyjoseph H, and Riveracorrea E (1978). Aedes-aegypti in Puerto-Rico - Environmental Determinants of Larval Abundance and Relation to Dengue Virus Transmission. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 27:1225-1231.

Morrison D, Legg TJ, Billings CW, Forrat R, Yoksan S, Lang J (2010). A novel tetravalent dengue vaccine is well tolerated and immunogenic against all 4 serotypes in flaviviurs naïve adults. Journal of Infectious Diseases 201(3): 370-377.

Pan W (2001). Akaike’s information criterion in generalized estimating equations. Biometrics 57:120-125.

Patz JA, Daszak P, Tabor GM, Aguirre AA, Pearl M, Epstein J, et al. (2004). Unhealthy landscapes: Policy recommendations on land use change and infectious disease emergence. Environmental Health Perspectives 112:1092-1098.

Reiter P, Amador MA, Anderson RA, and Clark GG (1995). Dispersal of Aedes aegypti in an Urban Area After Blood-Feeding as Demonstrated by Rubidium-Marked Eggs. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 52:177-179.

Rey JR, Nishimura N, Wagner B, Braks MAH, O’Connell SM, and Lounibos LP (2006). Habitat segregation of mosquito arbovirus vectors in south Florida. Journal of Medical Entomology 43:1134-1141.

Smith J, Amador M, and Barrera R (2009). Seasonal and habitat effects on dengue and West Nile virus vectors in San Juan, Puerto Rico. Journal of the American Mosquito Control Association 25:38-46.

StataCorp (2007). Stata Statistical Software: Release 10. Statacorp, College Station, Texas.

StataCorp (2011) Stata 12 help for xtgee. http://www.stata.com/help.cgi?xtgee. Accessed August 28, 2011.

Stoddard ST, Morrison AC, Vazquez-Prokopec GM, Soldan VP, Kochel TJ, Kitron U, Elder JP, Scott TW (2009). The Role of Human Movement in the Transmssion of Vector-Borne Pathogens. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 3(7): 1-9.

Troyo A, Fuller DO, Calderon-Arguedas O, and Beier JC (2008). A geographical sampling method for surveys of mosquito larvae in an urban area using high-resolution satellite imagery. Journal of Vector Ecology 33:1-7.

Troyo A, Fuller DO, Calderon-Arguedas O, Solano ME, and Beier JC (2009). Urban structure and dengue incidence in Puntarenas, Costa Rica. Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography 30:265-282.

Tun-Lin W, Kay BH, and Barnes A (1995). The Premise Condition Index: a tool for streamlining surveys of Aedes aegypti. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 53:591-594.

Tun-Lin W, Burkot TR, and Kay BH (2000). Effects of temperature and larval diet on development rates and survival of the dengue vector Aedes aegypti in north Queensland, Australia. Medical and Veterinary Entomology 14:31-37.

Vanwambeke SO, Lambin EF, Eichhorn MP, Flasse SP, Harbach RE, Oskam L, et al. (2007). Impact of land-use change on dengue and malaria in northern Thailand. Ecohealth 4:37-51.

Vanwambeke SO, Bennett SN, and Kapan DD (2011). Spatially disaggregated disease transmission risk: land cover, land use and risk of dengue transmission on the island of Oahu. Tropical Medicine & International Health 16:174-185.

WHO (2009) The World Health Organization: Dengue/dengue haemorrhagic fever. http://www.who.int/csr/disease/dengue/en/. Accessed September 15, 2010

Williams CR, Long SA, Russell RC, Ritchie SA (2006). Field efficacy of the BG-Sentienal compared with CDC backpack aspirators and CO2-baited EVS traps for collection of adult Aedes aegypti in Cairns, Queensland, Australia. Journal of the American Mosquito Control Association. 22: 296-300.

Williams CR, Long SA, Webb CE, Bitzhenner M, Geier M, Russell RC, et al. (2007). Aedes aegypti population sampling using BG-Sentinel traps in North Queensland Australia: Statistical considerations for trap deployment and sampling strategy. Journal of Medical Entomology 44:345-350.

Wilson M (2002) Dengue in the Americas. http://www.searo.who.int/en/Section10/Section332/Section1581.htm. Accessed September 15, 2010

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Little, E., Barrera, R., Seto, K.C. et al. Co-occurrence Patterns of the Dengue Vector Aedes aegypti and Aedes mediovitattus, a Dengue Competent Mosquito in Puerto Rico. EcoHealth 8, 365–375 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10393-011-0708-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10393-011-0708-8