Abstract

Aim

This paper aims to explain how political culture has influenced the scope of prevention measures, disease surveillance, and health data integration strategies in the German health system to date.

Subject and methods

Political culture is a major determinant of national health policies in countries, defining the means and scope of governmental authority for ensuring population health. This paper explains the role of political culture in shaping prevention and health promotion measures in the German health system, based on a public policy theory.

Results

During the post-war period, the structure of the German health system was (re-)designed to focus on curative medicine at the expense of public health. Current prevention and health promotion measures, often characterised as ‘too little, too late’, lead to medical treatments that are ‘too costly, too risky’. Linking data sources in Germany today is much more challenging than in other European countries, with health-relevant data often remaining in isolated silos that could be used for population health.

Conclusion

The analysis suggests that the national heritage shaping the political culture in Germany had a great influence on the limited role of government intervention, the interpretation of public health, and the state’s role in collecting and processing health data of citizens for research and policymaking.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Ensuring access to the right information at the right time improves the safety, effectiveness, and efficiency of care (OECD 2021a). Data collected from patients can be used to make better-informed decisions and deliver more effective health services. Considered one of the most useful tools in this context, cross-sectoral electronic health records (EHRs) help achieve preventive, person-centred and integrated care by merging relevant clinical information across different healthcare sectors. Besides clinical benefits, data integration facilitated by EHRs can enable relevant national authorities to access patient history, leading to more coordinated public health measures. Indeed, data obtained from EHRs can be an important resource for enhanced public health surveillance and monitoring, targeted interventions for vulnerable populations, and improved disease management and prevention at the population level. In several European countries, researchers and policymakers use EHR data for developing preventive health policies such as optimising patient pathways or developing clinical guidelines, health promotion programmes, and national health plans and priorities (OECD 2017). As such, EHR data may not only enable healthcare providers to comprehend the clinical picture of their patients in more detail and treat them more effectively but also support decision-makers in better-informed policymaking. However, despite the benefits, data collected through personal EHRs might fall short in providing a comprehensive understanding to identify the root causes of diseases and address them at the population level (Haneef et al. 2020).

Combining data from different sources can provide a much more comprehensive picture of the health of the people than could be obtained from any single source. In this way, the effects of physical, built and social environments (e.g. green space, food deserts, community socioeconomic deprivation) on an individual’s health (e.g. hypertension, diabetes, migraines) can be discovered and more effectively managed (Casey et al. 2016). When EHR data are linked to different datasets that include key population-wide information, they can contribute to building robust national health information systems (HISs) that could prevent or diminish the burden of diseases at the population level (Lippeveld et al. 2000). A well-functioning HIS has three main characteristics (Health Metrics Network and World Health Organization 2008): (i) producing data on individual, facility and population levels from multiple sources, including but not limited to, public health surveillance systems, EHRs, civil registration data, household surveys and health service coverage information; (ii) having the ability to identify, scrutinise, communicate and control events that pose a risk to public health at their location of occurrence and as soon as they happen; (iii) having the capability to merge the collected data from different sources effectively and improve both the demand for and supply of data. Linking personal health data through HIS can literally be ‘a matter of life or death’ not only in pandemics, such as Covid-19, but also for understanding disease causality and offering targeted preventive measures at the population level. Typically, national public health authorities play a crucial role in collecting relevant data and building HISs.

In Germany, collecting personal data and linking data sources are more challenging compared to other European countries, with health-relevant data often remaining in isolated silos (March et al. 2018). One of the reasons is that data security is an overemphasised concern in the country (Heidel and Hagist 2020; Schmitt et al. 2023a, b). A study comparing privacy and data protection rules in eight European Union (EU) Member States reports that Germany is the frontrunner in most data security aspects, having by far the largest number of privacy officers and being the only country that legally obliges to appoint a privacy officer in specific matters concerning healthcare (Custers et al. 2018). Apart from the EU Regulations such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), the federal data protection laws, state legislations in 16 federal states (Bundesländer) and state-specific hospital laws must be considered for the re-use of health data in Germany (Dtsch Arztebl 2023). Many of these laws fail to fully address the importance of secondary data usage in today’s interconnected world, hindering the digital transformation in healthcare (Dtsch Arztebl 2023). Indeed, during the Covid-19 pandemic one of the main barriers to public (health) authorities extracting data from hospitals’ EHRs has been the country’s federal structure with different legal frameworks at different levels that determine whether data may be used for secondary purposes (OECD 2021b). The absence of a unique personal identification number hampers cross-sectoral linkages for health and care, and a linkage between different datasets that contain personal information is only permitted with prior consent of the person concerned (SVR Gesundheit 2021).

Approach

According to Leichter (1979), cultural factors belong to one of four main categories that have an influence on public policies. Political culture, being one of the two sub-categories of cultural factors, incorporates (i) national heritage; (ii) political norms and values; and (iii) formal political ideology (Leichter 1979). Shaping the set of values, beliefs, expectations and attitudes concerning what the government should or should not do, political culture defines not only how government should operate but also what the proper relationship between the citizen and the state is, e.g. whether citizens accept authoritarian policies or not is a matter of political culture. As such, political culture focuses on the interaction between the legitimacy, effectiveness and recognition of democracy, and it is closely linked to the legitimacy of the political system in a country and trust in its institutions (Pickel and Pickel 2023). Political culture is shaped over generations, evolving historically and showing variability across different age groups (Conradt 2002, 2015). It shapes the proper, acceptable role of government based on citizens’ beliefs and assumptions about government; political culture can thus either support or obstruct active government intervention in solving problems (Leichter 1979). In other words, it determines not only what people value but also how and by whom they expect matters that concern them to be handled.

Against this background, it can be stated that political culture is a major determinant of national health policies in Germany, defining the means and scope of governmental authority for ensuring population health. Despite some differences in political culture between the western and eastern parts of the country, owing to their historical contexts, the legitimacy of democracy is widely accepted in Germany (Pickel and Pickel 2023). Traditionally, however, the guiding principles of the German health system have been decentralisation and non-state operations, which shape what kind of policy instruments are considered to be politically feasible or acceptable (Altenstetter 2003). As will be discussed in detail below, impactful events in German history have been one of the main reasons for the non-state operations in health policies. These events shaped health system governance, which continues to affect effective health promotion and prevention strategies at the population level even today. The most obvious embodiment of the negative consequences of the past events was seen during the Covid-19 pandemic with the state’s public health authorities (Öffentlicher Gesundheitsdienst; ÖGD) having limited resources, staff shortages, and a lack of digital infrastructure to share and link crucial health data (Expertenrat der Bundesregierung zu Covid-19 2022). On the basis of Leichter’s theory (1979), this paper seeks to explain how political culture has defined the scope of prevention and health promotion measures in Germany, as well as its approaches to disease surveillance and health data integration to date, while also providing recommendations for the future.

Health system in Germany

What public health entails in countries is often shaped by diverse perspectives and evolving societal values. In Europe, public health services are organised very differently mainly due to the varied nature of health systems. For instance, in Denmark, Portugal or the United Kingdom (UK), the term public health refers to the health system itself given that in those countries the system is financed through taxes, encompassing both preventive and curative services (Deutscher Bundestag 2012). Compared with other countries, it is a peculiarity of the German health system that social security has been primarily related to employment, without a direct connection to medical benefits. Unlike in a tax-financed health system, such as the UK, where curative and preventive elements in healthcare are combined and offered to the whole population, the health system in Germany was initially designed to focus on individualised treatments, with prevention and social services remaining under-emphasised compared to curative medicine (Lindner 2004). Prioritising the health recovery of employees to bring them back to the workforce led to the governance of healthcare provision and prevention being organised into two different administrative structures.

Today, although both healthcare provision and public health fall under the authority of the Federal Ministry of Health (MoH), a clear separation between the two administrative structures remains apparent in the German health system. The former is a form of universal health insurance, in which corporatist self-governing bodies of healthcare providers and sickness funds play a significant role in determining healthcare policies and practices. Known as the statutory health insurance (SHI), this system initially emerged as employee benefit but covers today most residents in the country. The SHI system is funded through contributions to sickness funds. The amount of contribution for each enrolee (employee) is based on their income, with contributions usually shared between them and their employers. In contrast to SHI, public health (ÖGD) is a state service for the ‘public concern for the health of all’. In line with the federal structure, the responsibilities of public health authorities (almost 400 across Germany) are determined by the respective health service laws agreed upon between the federal government, federal states, counties and municipalities (Beirat Pakt ÖGD 2021). The competences of the public health authorities for health promotion and disease prevention are remarkably underdeveloped, just as their digital and technical infrastructure for surveillance (Expertenrat der Bundesregierung zu Covid-19 2022).

Arguably, historical analysis is an inevitable part of health policy research, as it helps to disentangle short-term from long-term factors and raises sensitivity to how contemporary policymaking is bounded by powerful traditions (Altenstetter 2003). Triggered by the complex problems that could not be solved within the medical field, Germany (re-)discovered public health services in the 1980s and banked on national public health authorities in crises such as the Covid-19 pandemic. However, ÖGD has repeatedly failed to become a fundamental pillar of the health system. In this context, a brief history of public health in post-war Germany deserves discussion, not least because this profession could have built a holistic approach to health and well-being but failed to secure its place at the core of the health system. One of the main reasons for this missed opportunity lies in the political and organisational weakness of public health institutions that were not able to sustain and claim their services in the 1980s as an exclusive area of competence against other emerging public authorities in Germany, particularly concerning environmental protection, for which several new institutions were created in the same period (Rosewitz and Webber 1990). Yet, strikingly, the main setback to public health came from within the medical profession itself.

Public health and prevention in the post-war period

Throughout the twentieth century, Germany had more physicians than needed, and their dominance safeguarded curative medicine at the expense of public health (Leichter 1979). The concept of health promotion and prevention had remained neglected until office-based physicians and sickness funds claimed prevention as the area of responsibility of SHI (Lindner 2004; Rosewitz and Webber 1990). Indeed, owing to the glut of physicians, the medical profession in the post-war era tried to shift as many clinical tasks as possible from ÖGD to its area of competence under SHI (Kießling 2016). For instance, the Paediatric and Adolescent Medical Service of the Public Health Service (Der Kinder- und Jugendärztliche Dienst des Öffentlichen Gesundheitsdienstes; KJÄD-ÖGD) plays a bridging role between youth and social welfare on one hand, and the health system on the other. It has the responsibility to deliver compensatory healthcare aimed at improving access to health promotion and prevention measures for socially disadvantaged children (Thyen 2010). Unlike office-based physicians, who are restricted by advertising bans from making unsolicited house calls or soliciting clinic visits, KJÄD-ÖGD can actively provide follow-up and outreach care to effectively support these populations (Thyen 2010). However, after the maternal and child healthcare was transferred from ÖGD to SHI, it increasingly lost its importance and has been minimally used in the implementation of early intervention programmes (Thyen 2010). Notably, maternal and child health is not the only affected field. In line with the medicalisation trend that shaped the entire Western world in the 1950s and 1960s and aimed to address (public) health issues biologically instead of within a social construct, in Germany tasks that had previously been performed by the public health authorities were given to office-based physicians, including pre-/post-hospital treatments and prevention (Lindner 2004; Rosewitz and Webber 1990).

The task shift from ÖGD to SHI had an impact on the interpretation of prevention and the scope of activities undertaken to this end. Prevention was reconceptualised within SHI by determining what it should contain, how it should be executed and by whom, and perhaps even more importantly, which activities it should exclude. Narrowly defined preventive care in SHI was medicalised in the form of tests, images and diagnoses, such as screening programmes for children and early detection programmes for certain types of cancer, almost eliminating the role of public health in the health system (Rosewitz and Webber 1990). The new child screening programmes under SHI demolished an efficient and economical programme that had been run by public health authorities by moving that competence to office-based physicians, leading to unnecessary costs for the health system and an even weaker role for the public health sector (Busse et al. 2017; Rosewitz and Webber 1990). The cancer screening programmes, on the other hand, shifted the emphasis from preventive advice by public health officials to an increased number of medical tests conducted by office-based physicians. This limited approach to prevention, focused mostly on screenings and check-ups, was primarily driven by their financial motivations (Rosewitz and Webber 1990). In the 1970s, the government eventually recognised the drawbacks of the fragmented health system with prolonged hospital stays and superfluous examinations and technical diagnostics offered by office-based physicians, resulting in a steady expansion of SHI costs (Rosewitz and Webber 1990). The issue, however, remains unresolved even to this day (Schmitt and Haarmann 2023).

Yet, when discussing the roles that ÖGD assumed in the past, one should not overlook the dark chapter in history that contradicted the original benevolent purpose of public health authorities (Busse et al. 2017). ÖGD, in its present administrative form, was established under the Nazi regime that co-opted ÖGD infrastructures and ÖGD physicians as instruments in the barbaric policy system of racial hygiene, leading to a vast number of forced sterilisations and deaths (Busse et al. 2017). After the war, the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany) wanted to distinguish itself from the system of the German Democratic Republic, and as such, it was not open to any approaches towards state health service (Staatsmedizin). In other words, the stars were aligned for the medicalisation of preventive care services: Owing to its involvement in hereditary and racial hygiene during National Socialism, ÖGD fell into disrepute, while the concept of Staatsmedizin and state-provided prevention policies were stigmatised (Kießling 2016). In line with the political will of those times, the office-based physicians filled the vacuum and gained the monopoly for out-patient care with the Statutory Health Insurance Physicians Act (Kassenarztgesetz) in 1955, expanding their power vis-à-vis ÖGD, sickness funds and hospitals (Bandelow 2004; Kießling 2016; Lindner 2004).

Hence, the office-based physicians shaped the structures of the health system to focus on curative medicine and used the post-war period as an opportunity to discredit social and population medicine, which still has an impact on today’s public health system. They suggested their own prevention programmes as possible solutions to rising healthcare costs and increasing burden of diseases, which could resonate with the vision of the politicians belonging to conservative and liberal parties (Rosewitz and Webber 1990). To their advantage, the reformers from these political parties favoured early detection of disease and prevention only within the boundaries of SHI, and they were timid in advocating the reallocation of resources from the curative sector to prevention (Altenstetter 2003). Another reason for the success of the office-based physicians has been their ability to influence the opinion of patients, resulting in a high multiplier effect of their ‘voice’ and thus a potential threat to elected politicians (Mayntz and Scharpf 1995; Rosewitz and Webber 1990). For politicians, it has been extremely difficult to push through any law against the resistance of thousands of physicians, each of whom treats dozens of patients a day (Rosewitz and Webber 1990). The presumed influence of the medical profession on the political opinions of their patients led politicians to shy away from implementing measures that might (appear to) harm physicians’ interests (Mayntz and Scharpf 1995).

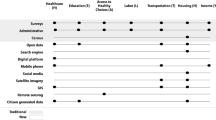

The victory of office-based physicians supported the credo of health data protection and reinforced the fragmentation between sectors. History provides good reasons to understand the distrust and disgust that Germans feel towards state surveillance (Arora 2020), favouring minimal data retention (Hornung and Schnabel 2009). Despite its potentially altruistic goal, the collection of personal information is still perceived as inherently dangerous, given that ‘Germans experienced first-hand what happens when the government knows too much about someone’ (Arora 2020), as occurred during both the Nazi and later Soviet eras in Germany. Even today, while citizens express a high willingness to share data with office-based physicians, and to a slightly lesser degree with sickness funds (acatech and Körber-Stiftung 2022), there is noticeable reluctance when it comes to governmental data custodians (Fig. 1). Hence, a negative image of public health under Staatsmedizin along with an unfavourable technical infrastructure, unclear and unexciting competencies and low salaries made public health not a main pillar but only a marginal area of the German health system (Rosewitz and Webber 1990). Parallel to this, a deliberate fragmentation in healthcare provision under SHI, characterised by a dominance of curative medicine over prevention, along with the dispersion of relevant data across separated silos and a delayed interest in health services research led to high expenditures in the German health system (Lindner 2004; Schmitt and Haarmann 2023); indeed, the highest among all EU countries both in terms of the share of gross domestic product (GDP) and spending per capita (OECD and European Union 2022).

Is prevention possible without a strong public health approach in the modern era?

Purely biological explanations for ill-health and diseases, dominated by technical knowledge, fail to consider factors outside medicine that might improve people’s health. With the rising costs of healthcare provision, welfare states aimed to reduce the power of the medical profession in the 1980s to ensure cost stability and look for ways to minimise waste and inefficiencies in healthcare provision, giving more importance to preventive care and public health (Walt 2004). However, traditionally, physicians in European countries have been seen as holding dominant and monopolistic positions within the health sector (Immergut 1990; Walt 2004). They resisted regulatory actions such as the establishment of national health insurance systems given that they perceived such government-backed insurance schemes and the likely subsequent increase in regulatory oversight as threats to their professional independence (Immergut 1990). Physicians moreover exerted considerable control over the training and regulation of their members and subordinated other health professionals to their authority. Although public health policies that use mechanisms such as education, preventative treatments or screenings have been proven to effectively improve health and reduce inequalities (Thomson et al. 2018), they might be difficult to implement against the will of physicians. Indeed, in Germany measures that had been planned or even already legislated were often implemented much later or in a completely different form due to physicians’ significant influence on health policies (Lindner 2004). It thus became one of the greatest challenges of governments in welfare states to keep the working population productive while maintaining the cost of healthcare and long-term care services at a sustainable level (Walt 2004).

Reflecting on the past few years in Germany, an encouraging step towards public health and HIS was taken during the Covid-19 pandemic. With the Patient Data Security Act (Patientendaten-Schutz-Gesetz) in 2020, the possibility of connecting ÖGD to the national telematics infrastructure was created, allowing the physicians working for ÖGD to access the national EHR system, known as elektronische Patientenakte or ePA for short (Bundesgesetzblatt 2020). In the same year, the federal government committed to provide financial resources amounting to a total of EUR 4 billion by 2026; the promised pact (Pakt für den ÖGD) aims to reinforce the personnel in public health services and improve the technical and digital infrastructure (Beirat Pakt ÖGD 2021). Moreover, for the digital and technical strengthening of ÖGD, Germany requested funds amounting to almost EUR 815 thousand from the Recovery and Resilience Facility as part of the EU’s plan following the Covid-19 pandemic (Bundesministerium der Finanzen 2022). Yet a few years later, in 2023, the government also signalled the absence of follow-up financing after 2026, stating that the support to ÖGD was more an exception due to the pandemic than a rule (ÄrzteZeitung 2023a). This is highly likely to increase tension between the federal government and the federal states, given that the ongoing costs in ÖGD will not end in 2026 and are expected to be borne by the federal states themselves (ÄrzteZeitung 2023b). As becomes clear, thus far neither the federal government nor healthcare providers has conceded an eminent policy role to ÖGD, and it is questionable whether they will ever redistribute political power from curative medicine to public health at the expense of office-based physicians and sickness funds as the traditional stakeholders of SHI (Ewert and Loer 2022).

Striking the balance between data privacy and public health surveillance

Despite the cost-effectiveness, countries still fail to invest sufficiently in health promotion and disease prevention due to hesitation to support initiatives that may not yield positive results for a long time and the challenge stakeholders face in attributing these benefits specifically to health promotion (WHO/Europe 2020). It is now well known that the challenge of achieving health data integration, which could support preventive, person-centred and integrated care, is not merely of a technical nature. Rather, this process requires substantial changes in the organisation of health service provision and the related legal and financial frameworks that support sharing of information and incentivising collaboration of the health workforce in different sectors (OECD 2021a). Several European countries are well ahead in delivering integrated care while still being able to fully comply with GDPR (OECD 2021b). However, most of the time, on the national or international stage, data security issues or GDPR are cited as reasons for inaction or stagnation in digitally integrated healthcare in Germany, which may be only the tip of the iceberg (Schmitt et al. 2023a, b). Issues concerning political culture can take place in different forms and are articulated in different words, such as citizens’ trust in governments (Belfrage et al. 2021). Similarly, when introducing EHRs in Germany, studies show that to gain the necessary trust from patients and health professionals, information on EHRs should be provided to patients by their healthcare providers instead of the state itself (Ploner et al. 2019). However, when making such recommendations, one should be mindful of physicians’ own interests. Their publicly articulated concerns over protecting the doctor-patient relationship or data privacy could be a strategic argument to hinder transparency (Bogumil-Uçan and Klenk 2021; SVR Gesundheit 2021); a transparency that could lead to negative financial or reputational impacts on the physicians themselves (SVR Gesundheit 2021).

Indeed, the confidentiality argument may be misused by physicians and policy actors to hinder innovations or avoid any substantial discussions on deeply rooted weaknesses of the health system (Pohlmann et al. 2020). Physicians in Germany have good means to articulate their concerns through their well-organised interest representation vis-à-vis political institutions and have been particularly vocal in ‘patient privacy’ matters when it comes to implementing data-driven innovations (BÄK 2005, 2012; Schmitt 2023). Such statements can intensify the atmosphere of public distrust, undermining confidence in the government’s ability to prevent patients’ data from falling into the wrong hands and to maintain health data sovereignty. This distrust can then spill over to the payer organisations, with the apprehension that any collected health information could be used to adjust, i.e. increase, employee contributions to SHI (Ploner et al. 2019). On the contrary, if patients are highly satisfied with their sickness funds, this experience can have a positive spill-over effect on their attitude towards transparency (Henkenjohann 2021). Studies analysing health data sharing practices in Germany show patients’ willingness to share their EHRs data if it was proven to be helpful in managing their illnesses (Baudendistel et al. 2015). This indicates the need for better communication of the benefits of health data to patients, or more broadly, citizens.

Potential solutions

Unlike immediate benefits directed to the individuals concerned, the concept of re-use of health data is less tangible to many people and requires the communication of clear use cases that could show concrete results (Schmitt et al. 2023a, b). This should go hand-in-hand with the ongoing efforts to improve digital health literacy in Germany, which has been found to be insufficient across all segments of the population (Schaeffer et al. 2023). The current prevention and health promotion measures, often characterised as ‘too little, too late’, lead to medical treatments that are ‘too costly, too risky’. To reverse this trend, Germany could expand its ÖGD staff and enhance academic roles in public health, such as professorships and postdoctoral positions (Dragano et al. 2016). An improved integration of ÖGD with academic institutions could be financially supported, for instance, by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research to build ‘Public Health Partnerships’ (Dragano et al. 2016). In addition, to make ÖGD part of a transformative health system that prioritises prevention over curative medicine, public health could be involved in the planning of medical care and financial resources (Beirat Pakt ÖGD 2021). This implies the amalgamation of the SHI and ÖGD systems, which thus far have been strictly separated in administrative terms. Moreover, for reliable health reporting, surveillance, and monitoring that could enable solid health planning in the future, all relevant information sources in a particular region should be made available to ÖGD. This would include environment-related data in that geographic region, scientific literature, registries and patient data in the SHI system such as through EHRs (Beirat Pakt ÖGD 2021), which could enable the creation of a robust HIS in that region. Studies could be conducted to explore whether not only patients but also citizens have a positive attitude towards the creation of comprehensive HISs with data linkages.

Taking this idea one step further, regular citizen dialogues could be organised to discuss the implications of digitalisation on modern health systems. In this context, the representation not only of patients but also citizens from various age groups would be important given that creating a robust HIS is less about managing diseases and more about preventing them from occurring or spreading within the population. Currently, even patients have merely an advisory role, without decision-making power, when self-governing bodies of physicians and sickness funds make health policies at the Federal Joint Committee (G-BA 2023). It would thus be imperative to also give decision-making power to patients and, even more importantly, to incorporate citizen engagement approaches such as citizens’ councils, while adhering to the principle of representative democracy. The citizen dialogues conducted in the initiative Neustart by the Robert Bosch Foundation represent a laudable example of this concept (Robert Bosch Stiftung 2020). Moreover, interdisciplinary consortia and network organisations for better use of health data could be further supported. For instance, within the framework of the National Research Data Infrastructure (Nationale Forschungsdateninfrastruktur; NFDI) NFDI4Health as a consortium enables further scientific use of data from medical studies (Leibniz Institute for Prevention Research and Epidemiology 2018), and Technology and Methods Platform for Networked Medical Research (Technologie- und Methodenplattform für die vernetzte medizinische Forschung e.V.; TMF) fosters research, networking and digitalisation in medicine (TMF e.V. 2024). They both successfully work on the secondary use of health data in Germany and play a key role in integrating scientific developments with political context.

In summary, reasons for healthcare fragmentation and substantial deficiencies in the effective monitoring and prevention of diseases at the population level in Germany today lie in the weak, if not non-existent, interest representation of the public health profession and patients at the political level (Bandelow 2004). Within a political vacuum, where office-based physicians dominated the space against Staatsmedizin, public health authorities were compelled to accept minimal resources or influence on health policies (Rosewitz and Webber 1990). The shameful activities of ÖGD in the past caused serious damage to the reputation of public health in Germany, which was, and still is, hard to overcome even after decades. Parallel to this, the opinions of patient interest groups have been disregarded or undervalued in the rigid hierarchies and authoritarian structures of the healthcare administration, coupled with an underdeveloped culture of participation in Germany (Lindner 2004). Even in the 2000s, the ‘modern’ patient, who articulates their interests and concerns, was found to be absent in the country, in contrast to the UK (Lindner 2004). Given that patients or citizens have been the weakest group in health policymaking in Germany, a health system that puts them first can only exist if they advocate for their own interests (Caumanns 2019). Ultimately, the empowerment of citizens should entail introducing a new dimension to health data sharing: balancing individuals’ rights on the one hand with ensuring population health on the other.

Conclusion

This article discussed data sharing practices for public health and prevention in Germany in the context of political culture. Understanding political culture is important, especially for those who want to draw meaningful lessons from cross-national policy differences and design policy transfers, given that what may be considered feasible in one system may not be so considered in another. On the basis of the insights provided, it can be concluded that the national heritage shaping the political culture in Germany had a great influence on the limited role of government intervention, the interpretation of public health, and the state’s role in collecting and processing health data of citizens for research and policymaking. The constitution of the World Health Organization suggests that ‘health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity’ (World Health Organization 2020). Understanding health as such, keeping the population in Germany healthy spans a range of thematic areas, from democracy to digital civil rights, from federalism to the use and re-use of health-relevant data. Experience from the past few years during and after the Covid-19 pandemic suggests that overly protective behaviours concerning data security is neither in the best interest of individuals nor of the public. However, embracing the advantages of health data sharing still has a long way to go in Germany. Patient empowerment, research and networking consortia, and citizen dialogues about this topic could pave the way for discussions on how to renew public health efforts, respect individual choices and better tailor the health system to the needs of the population.

Availability of data and material

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Acatech, Körber-Stiftung (2022) TechnikRadar 2022. Was die Deutschen über Technik denken. https://koerber-stiftung.de/site/assets/files/17226/technikradar-2022-langfassung.pdf. Accessed 19 Aug 2024

Altenstetter C (2003) Insights from health care in Germany. Am J Public Health 93(1):38–44. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.93.1.38

Arora K (2020) Privacy and data protection in India and Germany: a comparative analysis. Berlin Social Science Center. https://bibliothek.wzb.eu/pdf/2020/iii20-501.pdf. Accessed 19 Aug 2024

ÄrzteZeitung (2023a) Gesundheitsausschuss will Bundesmittel für Gesundheitsämter nicht verlängern. https://www.aerztezeitung.de/Politik/Gesundheitsausschuss-will-Bundesmittel-fuer-Gesundheitsaemter-nicht-verlaengern-437875.html. Accessed 19 Aug 2024

ÄrzteZeitung (2023b) Landkreistag: ÖGD-Reform braucht dauerhafte Finanzierung. https://www.aerztezeitung.de/Politik/Landkreistag-OeGD-Reform-braucht-dauerhafte-Finanzierung--439418.html. Accessed 19 Aug 2024

BÄK (2005) IT Kompakt—Informationsdienst zur Telematik im Gesundheitswesen, no. 2. Bundesärztekammer. www.baek.de. Accessed 19 Aug 2024

BÄK (2012) Entschließung des 115. Deutschen Ärztetages zur eGK. https://www.bundesaerztekammer.de/aerztetag/aerztetage-der-vorjahre/115-daet-2012-in-nuernberg/presseinformationen/egk/. Accessed 19 Aug 2024

Bandelow N (2004) Akteure und Interessen in der Gesundheitspolitik. Vom Korporatismus zum Pluralismus? Politische Bildung 37(2):49–63

Baudendistel I, Winkler E, Kamradt M, Längst G, Eckrich F, Heinze O, Bergh B, Szecsenyi J, Ose D (2015) Personal electronic health records: understanding user requirements and needs in chronic cancer care. J Med Internet Res 17(5):e3884. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.3884

Beirat Pakt ÖGD (2021) Empfehlungen zur Weiterentwicklung des ÖGD zur besseren Vorbereitung auf Pandemien und gesundheitliche Notlagen. https://www.bundesgesundheitsministerium.de/fileadmin/Dateien/3_Downloads/O/OEGD/2021_10_Erster_Bericht_Beirat_Pakt_OeGD.pdf. Accessed 19 Aug 2024

Belfrage S, Lynöe N, Helgesson G (2021) Willingness to Share yet maintain influence: a cross-sectional study on attitudes in Sweden to the use of electronic health data. Public Health Ethics 14(1):23–34. https://doi.org/10.1093/phe/phaa035

Bogumil-Uçan S, Klenk T (2021) Varieties of health care digitalization: comparing advocacy coalitions in Austria and Germany. Rev Policy Res 38(4):478–503. https://doi.org/10.1111/ropr.12435

Bundesgesetzblatt (2020) Gesetz zum Schutz elektronischer Patientendaten in der Telematikinfrastruktur (Patientendaten-Schutz-Gesetz – PDSG). Bundesanzeiger Verlag. https://www.bundesgesundheitsministerium.de/fileadmin/Dateien/3_Downloads/Gesetze_und_Verordnungen/GuV/P/PDSG_bgbl.pdf. Accessed 19 Aug 2024

Bundesministerium der Finanzen (2022) Deutscher Aufbau- und Resilienzplan (DARP)—Komponente 5.1 Stärkung eines pandemieresilienten Gesundheitssystems. https://www.bundesfinanzministerium.de/Content/DE/Standardartikel/Themen/Europa/DARP/2-08-pandemieresilientes-gesundheitssystem.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=5. Accessed 19 Aug 2024

Deutscher Bundestag (2012) Die Organisation des Öffentlichen Gesundheitsdienstes in EU-Mitgliedstaaten. https://www.bundestag.de/resource/blob/410526/d00d4971143baf87fa5c49e769c6206e/wd-9-034-12-pdf-data.pdf. Accessed 19 Aug 2024

Busse R, Blümel M, Knieps F, Bärnighausen T (2017) Statutory health insurance in Germany: a health system shaped by 135 years of solidarity, self-governance, and competition. Lancet 390(10097):882–897. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31280-1

Casey JA, Schwartz BS, Stewart WF, Adler NE (2016) Using electronic health records for population health research: a review of methods and applications. Annu Rev Public Health 37(1):61–81. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032315-021353

Caumanns J (2019) Zur Diskussion: Stand der Digitalisierung im deutschen Gesundheitswesen. Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes 143:22–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.zefq.2019.04.002

Conradt DP (2002) Political culture in unified Germany: the first ten years. German Polit Soc 20(2):43–74. https://doi.org/10.3167/104503002782385381

Conradt DP (2015) The civic culture and unified Germany: an overview. German Politics 24(3):249–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644008.2015.1021795

Custers B, Dechesne F, Sears AM, Tani T, van der Hof S (2018) A comparison of data protection legislation and policies across the EU. Comput Law Secur Rev 34(2):234–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clsr.2017.09.001

Dragano N, Gerhardus A, Kurth BM, Kurth T, Razum O, Stang A, Teichert U, Wieler LH, Wildner M, Zeeb H (2016) Public health – mehr Gesundheit für alle. Das Gesundheitswesen 78(11):686–688. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0042-116192

Dtsch Arztebl (2023) Gesundheitsdaten: Paradigmenwechsel steht auch in Deutschland bevor. https://www.aerzteblatt.de/archiv/232481/Gesundheitsdaten-Paradigmenwechsel-steht-auch-in-Deutschland-bevor. Accessed 19 Aug 2024

Ewert B, Loer K (2022) COVID-19 as a catalyst for policy change: the role of trigger points and spillover effects. German Politics 32(4):738–761. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644008.2022.2088733

Expertenrat der Bundesregierung zu Covid-19 (2022) 4. Stellungnahme des ExpertInnenrates der Bundesregierung zu COVID-19—Dringende Maßnahmen für eine verbesserte Datenerhebung und Digitalisierung. https://www.bundesregierung.de/resource/blob/974430/2000794/f189a6b7b0f581965f746e957db90af7/2022-01-22-nr-4expertenrat-data.pdf?download=1. Accessed 19 Aug 2024

G-BA (2023) Structure, members, patient involvement. https://www.g-ba.de/english/structure/. Accessed 19 Aug 2024

Haneef R, Delnord M, Vernay M, Bauchet E, Gaidelyte R, Van Oyen H, Or Z, Pérez-Gómez B, Palmieri L, Achterberg P, Tijhuis M, Zaletel M, Mathis-Edenhofer S, Májek O, Haaheim H, Tolonen H, Gallay A (2020) Innovative use of data sources: a cross-sectional study of data linkage and artificial intelligence practices across European countries. Arch Public Health 78(1):55. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-020-00436-9

Health Metrics Network, World Health Organization (2008) Framework and standards for country health information systems. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43872. Accessed 19 Aug 2024

Heidel A, Hagist C (2020) Potential benefits and risks resulting from the introduction of health apps and wearables into the German statutory health care system: scoping review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 8(9):e16444. https://doi.org/10.2196/16444

Henkenjohann R (2021) Role of individual motivations and privacy concerns in the adoption of German electronic patient record apps—a mixed-methods study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(18):9553. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189553

Hornung G, Schnabel C (2009) Data protection in Germany II: recent decisions on online-searching of computers, automatic number plate recognition and data retention. Comput Law Secur Rev 25(2):115–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clsr.2009.02.008

Immergut EM (1990) Institutions, veto points, and policy results: a comparative analysis of health care. J Publ Policy 10(4):391–416. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X00006061

Kießling A (2016) Der deutsche Sozialstaat als Sozialversicherungsstaat und seine Auswirkungen auf das Präventionsrecht. Rechtswissenschaft 7(4):597–624. https://doi.org/10.5771/1868-8098-2016-4-597

Leibniz Institute for Prevention Research and Epidemiology (2018) NFDI4Health. https://www.nfdi4health.de/en/. Accessed 19 Aug 2024

Leichter HM (1979) A comparative approach to policy analysis: health care policy in four nations. Cambridge University Press

Lindner U (2004) Gesundheitspolitik in der Nachkriegszeit: Großbritannien und die Bundesrepublik Deutschland im Vergleich (Vol. 57). R. Oldenbourg Verlag

Lippeveld T, Sauerborn R, Bodart C (2000) Design and implementation of health information systems. World Health Organization. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/42289. Accessed 19 Aug 2024

March S, Antoni M, Kieschke J, Kollhorst B, Maier B, Müller G, Sariyar M, Schulz M, Enno S, Zeidler J, Hoffmann F (2018) Quo vadis Datenlinkage in Deutschland? Eine Erste Bestandsaufnahme Das Gesundheitswesen 57(3):e20–e31. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0043-125070

Mayntz R, Scharpf FW (1995) Steuerung und Selbstorganisation in staatsnahen Sektoren. In: Gesellschaftliche Selbstregelung und politische Steuerung. Campus

OECD (2017) Readiness of electronic health record systems to contribute to national health information and research (OECD health working papers 99; OECD health working papers, vol. 99). https://doi.org/10.1787/9e296bf3-en

OECD (2021a) Empowering the health workforce—Strategies to make the most of the digital revolution. OECD Publishing. https://www.oecd.org/health/health-systems/Empowering-Health-Workforce-Digital-Revolution.pdf. Accessed 19 Aug 2024

OECD (2021b) Survey results: national health data infrastructure and governance (OECD Health working papers 127; OECD health working papers, vol. 127). https://doi.org/10.1787/55d24b5d-en

OECD, European Union (2022) Health at a glance: Europe 2022: state of health in the EU Cycle. OECD. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/health-at-a-glance-europe-2022_507433b0-en. Accessed 19 Aug 2024

Pickel S, Pickel G (2023) The wall in the mind – revisited stable differences in the political cultures of western and Eastern Germany. German Politics 32(1):20–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644008.2022.2072488

Ploner N, Neurath MF, Schoenthaler M, Zielke A, Prokosch HU (2019) Concept to gain trust for a German personal health record system using public cloud and FHIR. J Biomed Inform 95:103212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103212

Pohlmann S, Kunz A, Ose D, Winkler EC, Brandner A, Poss-Doering R, Szecsenyi J, Wensing M (2020) Digitalizing health services by implementing a personal electronic health record in Germany: qualitative analysis of fundamental prerequisites from the perspective of selected experts. J Med Internet Res 22(1):e15102. https://doi.org/10.2196/15102

Robert Bosch Stiftung (2020) Bürgerreport 2020—Reformschritte aus Bürgersicht. Robert Bosch Stiftung GmbH. https://www.neustart-fuer-gesundheit.de/. Accessed 19 Aug 2024

Rosewitz B, Webber D (1990) Reformversuche und Reformblockaden im deutschen Gesundheitswesen. Campus

Schaeffer D, Gille S, Berens EM, Griese L, Klinger J, Vogt D, Hurrelmann K (2023) Digitale Gesundheitskompetenz der Bevölkerung in Deutschland: Ergebnisse des HLS-GER 2. Das Gesundheitswesen 85(04):323–331. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-1670-7636

Schmitt T (2023) Implementing electronic health records in Germany: lessons (Yet to Be) learned. Int J Integr Care 23(1):13. https://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.6578

Schmitt T, Haarmann A (2023) Financing health promotion, prevention and innovation despite the rising healthcare costs: how can the new German government square the circle? Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes 177:95–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.zefq.2022.10.001

Schmitt T, Cosgrove S, Pajić V, Papadopoulos K, Gille F (2023a) What does it take to create a European health data space? International commitments and national realities. Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes 179:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.zefq.2023.03.011

Schmitt T, Haarmann A, Shaikh M (2023b) Strengthening health system governance in Germany: looking back, planning ahead. Health Econ Policy Law 18(1):14–31. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1744133122000123

SVR Gesundheit (2021) https://www.svr-gesundheit.de/gutachten/gutachten-2021/. Accessed 19 Aug 2024

Thomson K, Hillier-Brown F, Todd A, McNamara C, Huijts T, Bambra C (2018) The effects of public health policies on health inequalities in high-income countries: an umbrella review. BMC Public Health 18(1):869. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5677-1

Thyen U (2010) Kinderschutz und Frühe Hilfen aus Sicht der Kinder- und Jugendmedizin. Bundesgesundheitsblatt - Gesundheitsforschung - Gesundheitsschutz 53(10):992–1001. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00103-010-1126-8

TMF e.V. (2024) Startseite. https://www.tmf-ev.de/. Accessed 19 Aug 2024

Walt G (2004) Health policy: an introduction to process and power, 7th edn. Witwatersrand University Press, Johannesburg

WHO/Europe (2020) Building on value-based health care: Towards a health system perspective. https://eurohealthobservatory.who.int/publications/i/building-on-value-based-health-care-towards-a-health-system-perspective. Accessed 19 Aug 2024

World Health Organization (2020) Basic documents—forty-ninth edition. https://apps.who.int/gb/bd/pdf_files/BD_49th-en.pdf. Accessed 19 Aug 2024

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the Robert Bosch Stiftung. The Foundation had no role in the study design, execution, analysis, and writing of the paper.

Funding

This study was funded by the Robert Bosch Stiftung. The Foundation had no role in the study design, execution, analysis, and writing of the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TS writing (original draft), PSB writing (editing and revising).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Research involving human participants and/or animals

Not applicable.

Informed consent

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Schmitt, T., Schröder-Bäck, P. The role of national heritage in shaping Germany’s public health and data governance. J Public Health (Berl.) (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-024-02337-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-024-02337-5