Abstract

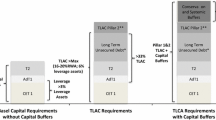

The new regulatory framework imposes an increase in capital requirements for banks. Although core capital (equity) is more expensive than other liabilities (debt), it strengthens banks’ stability and improves its loss-absorbing capacity. In this paper, we investigate the link between high-quality capital requirements and systematic risk. We further analyze the extent to which an improvement in the quality of the banks’ balance-sheet will affect the expected return on equity. We show the impact of shifts in funding structure on information asymmetries (especially implicit guarantees) and on the average funding cost. Our results demonstrate that core capital is essential for increasing banks stability and for reducing the average funding cost for banks. Our empirical analysis provides support for the introduction of strengthened prudential requirements defined in Basel III.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Miller and Modigliani (1958).

However, this is a different way of interpreting the theorem. Merton Miller himself acknowledges in his article published in 1988 that the way they have increased the definition of their theorem does not exactly express what they wanted to convey. The use of the term of ‘independence of the company’s value at the financing structure of the firm’ is rather strong, however it sets a benchmark. (“The view that capital structure is literally irrelevant or that ‘nothing matters’ in corporate finance, though still sometimes attributed to us (and tracing perhaps to the very provocative way we made our point), is far from what we ever actually said about the real world applications of our theoretical propositions. Looking back now, perhaps we should have put more emphasis on the other, more upbeat side of the ‘nothing matters’ coin: showing what doesn’t matter can also show, by implication, what does” (Miller (1988))

Among the determinants of beta we remind the costs structure: variables or fixed costs (if the company has mostly fixed costs, then it is more sensitive to the environment and thus its beta will be higher), the business sector, the growth rate of income and the funding structure.

With this assumption, a part of the volatility of the economic activity, more exactly the part of risk supported by creditors will be neglected. This can be justified by the existence of deposit insurance applied to deposits. For the other liabilities, this hypothesis is also appropriate: the risk under the CAPM is not the default risk but the market risk or the risk of fluctuations in the liabilities’ value correlated with the market.

In theory, this relationship has been verified. However, the assumption of the independence of beta assets with respect to the leverage and across time seems to us very strong and this even more in the current context of crisis. This was not the case if it was assumed that the banks ‘portfolios contain the majority of medium-and long-term claims, but descriptive statistics show that this represents only half of the banks’ balance sheets. The other assets that generate profits (eg. titles and securities) represent about one third of the bank’s balance sheet. This is why the issue of fluctuations in the total risk of bank assets from one year to another could depend on the economic environment and market liquidity. The assumption is also questioned from the point of view of the business model of the bank: banks can adopt their investment behavior based on the liability structure while respecting regulatory ratios (VanHoose (2007), Mc Kinsey (2011)).

The market premium P r is calculated as the difference between the expected market rate of return and the risk-free rate of return (E(R m ) − R f ). In our model the expected market rate of return is given by the historical returns on a market portfolio (for example CAC40 returns for French banks, FTSE 100 for English banks etc.). The risk free rate of return used for determining the risk premium is given by the interest rate of government bonds.

With the assumption of risk-free debt (Eq. 3a), the debt rate Rd is equal to the risk-free rate Rf.

Several banks went public after 1997. However we keep it in our database as they represent important entities for the banking system and for the economy.

We use CAC40 index for French banks, FTSE100 index for English banks, DAX index for German banks etc. We also estimate beta using a global index (S&P500). Results are similar.

Basel III is focusing on common equity as the capital component with the highest loss-absorbing capacity and on risk weighted assets as the most appropriate measure of balance sheet risk.

The Basel III capital requirements impose a capital ratio based on core capital, Common Equity Tier1 (CET1). Due to a very short historical data for this variable, we will use the Tier 1 capital in the calculation of leverage. This idea was also used in the literature Miles et al. (2012)) being justified by the strong correlation between the CET1 capital and Tier 1 capital.

A reduction in the proportion of debt reduces the covariance between the bank and the stock-market (through investors anticipations considered as reasonable).

It is difficult to assess the risk of bank assets. We first introduced assets characteristics as ROA, the liquidity ratio, the provisions for potential losses ratio, however these variables are not statistically significant. An alternative method is the integration of a volatility index of European equities VSTOXX. This asset risk index appears significant for our sample of European banks even when controlling for factors from year to year (Table 8 in appendix)

We use the nomination ‘Tier1 capital ratio’ in order to simplify the text. However, we refer to the main independent variable, the Tier1 capital to risk-weighted assets ratio.

We don’t consider for log beta as this variable has negative values for certain banks and certain periods.

As regards to macroeconomic control variables we use the economic cycle and the stock-markets return. Concerning banks’ specific characteristics, we use lending activity and market activity proportions in the balance-sheet, as well as the liquid assets ratio. These variables allow us to control for assets structure.

The banks in our sample are large banks (holdings). We thus assume that any support is issued by the government and there will not be a holding support. Moody’s issue a ‘support’ rating corresponding to the traditional rating and a ‘stand-alone’ rating excluding the government support. The Bank Financial Strength rating reflects how Moody’s appreciates the probability of an external intervention in cases of default. This last ration mentioned varies from A to E (A for a stable bank and E for a bank with high probability of future bailout). Starting from 2008 Moody’s issues also a ‘stand-alone’ rating similar to the ‘support’ rating (ratings from AAA to D). We are taking into account this last rating allows us to make a more meaningful comparison between the two cases.

In this paper we consider only for capital requirements of the new Basel III framework as defined in European Parliament Directive CRD IV (European Parliament 2011). Our choice could be restrictive for our analysis; however Modigliani-Miller, the main theoretical model used here refers only to capital amount of the balance sheet. In its initial form, it doesn’t take into account liquidity. It allows us to compute for the weighted average cost of capital only from a capital point of view. Our analysis is opposed to DeAngelo and Stulz (2013) affirming that high leverage is optimal for banks as they are discussing on the WACC evolution from a liquidity point of view. As a consequence, Modigliani-Miller theory could not be used in their context.

2002–2004 periods are not included in our sample of crisis periods as the shock didn’t had a major influence on the banking system or on our sample of European banks.

s This can be the result of the fact that depositors and creditors anticipate that they will be bailed out ex-post, so their ex-ante assessment of risk takes into account the existence of this government protection. Moreover, they have few incentives to monitor and supervise the risks banks can take. We could think that junior creditors would have more incentive in monitoring banks activity. But many holders of subordinated debt and even of hybrid products have been bailed out during the subprime crisis which clearly questioned their incentives to monitor.

References

Admati A, Hellwig M (2013) The bankers’ new clothes: What’s wrong with banking and what to do about it. Princeton University Press Princeton.

Admati A, de Marzo P, Helling M, Pfleiderer P (2011) Fallacies, Irrelevant Facts, and Myths in the Discussion of Capital Regulation: Why Bank Equity is Not Expensive. 2011, Stanford GSB Research Paper No. 2063

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) (2010a) Assessing the macroeconomic impact of the transition to stronger capital and liquidity requirements, 2010, Bank for International Settlements (BIS Interim Report)

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS). (2010b) An assessement of the long-term economic impact of the transition to stronger capital and liquidity requirements, 2010, Bank for International Settlements (BIS)

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) (2011) Basel III: A global regulatory framework for more resilient banks and banking systems. 2011, Bank for International Settlements.

BCE (2011) Financial Stability Review. 2011, pp. 125–157

BIS (2012) Post-crisis evolution of the banking sector. 2012, Annual Report, pp. 64–92

DeAngelo H, Stulz R (2013) Why high leverage is optimal for banks. No 19139, NBER Working Papers, National Bureau of Economic Research

Demirguc-Kunt A, Detragiache E, Merrouche O (2010) Bank capital : lessons from the financial crisis. 2010, Policy Research Working Paper Series 5473, The World Bank

Diamond DW, Rajan R (2009) Illiquidity and interest rate policy. 2009, NBER Working Papers no. 15197

Diamond DW, Rajan R (2011) Illiquid banks, financial stability and interest rate policy. 2011, NBER Working papers no.16994

Eliott D, Salloy S, Oliveira Santos A (2012) Assessing the cost of financial regulation, IMF Working Paper no. 12/233

European Banking Authority (EBA) (2012) Final report on the implementation of Capital Plans following the EBA’s 2011 Recommendation on the creation of temporary capital buffers to restore merket confidence

European Parliament Directorate General for Internal Policies Policy Department A: Economic and Scientific (2011) CRD IV – Impact assessment of the different measures within the capital requirements directive IV

Farhi E, Tirole J (2012) Collective moral hazard, maturity mismatch and systemic bailouts. 2012, American Economic Review vol 102, no 1

Hamada R (1971) The effet of the firm’s capital structure on the systematic risk of common stocks. The Journal of Finance, pp. 435–452

Hau H, Langfield, S, Marquez-Ibanez D (2012) Bank ratings;What determines their quality? s.l.: European Central Bank

Hyun J-S, Rhee B-K (2011) Bank capital regulation and credit supply. J Bank Fin 35:323–330

IMF (2011) Key Risks and Challenges for Sustaining Financial Stability. 2011, Global Financial Stability Report

Independent Commission on Banking (ICB) (2011) Final Report recommendations, September

Institute International Finance (IIF) (2010) Interim report on the cumulative impact on the global economy of proposed changes in the banking regulatory framework

Institute International Finance (IIF) (2011) The cumulative impact on the global economy of changes in the financial regulatory framework, Washington

Kashyap A, Stein JC, Hanson SG (2010) An analysis of the impact of ‘substantially heightened’ capital requirements on large financial institutions. Working paper

King M (2010) Mapping capital and liquidity requirements to bank lending spreads. 2010, Bank for International Settlements, Working paper no. 324

Kwast M, Passmore SW (2000) The Subsidy Provided by the Federal Safety Net: Theory and Evidence. 2000, J Fin Serv Res

Le Leslé, V, Avramova S (2012) Revisiting risk-weighted assets: why do RWAs differ across countries and what can be done about it?, 2012, IMF Working Paper, no. 12/90

Mc Kinsey (2011) Day of Reckoning: New Regulation and the Impact on Capital Market Business

Miles D, Yang J, Marcheggiano G (2012) Optimal bank capital. 2012, Econ J

Miller M (1977) Debt and taxes. 1977, J Fin:261–275

Miller M (1988) The Modigliani-Miller propositions after thirty years. 1988, J Econ Perspect:99–120

Miller M (1995) Do the M&M propositions apply to banks? 1995, J Bank Fin: 483–489

Miller M, Modigliani M (1961) Divident policy, growth, and the valuation of shares. 1961, J Bus:411–33

Miller M, Modigliani F (1958) The cost of capital, corporation finance and the theory of investment. 1958, Am Econ Rev:261–97

Noss J, Sowerbutts R (2012) The implicit subsidy of banks. s.l.: Bank of England, 2012

Oxera (2011) Assessing state support to the UK banking sector. s.l.: mimeo, 2011

Schich S, Lindh S (2012) Implicit Guarantees for Bank Debt: Where do we stand? s.l. : OECD J Fin Mark Trends 2012(1)

Stephen R (1988) Comment on the Modigliani-Miller propositions. 1988, J Econ Perspect:127–133

Ueda K, Weder di Mauro B (2012) Quantifying structural subsidy values for systemically important financial institutions. s.l.: IMF, 2012. WP/12/128

VanHoose D (2007) Assessing banks’ cost of complying with Basel II. Networks Financial Institute Policy Brief No. 2007-PB-10

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

I am extremely grateful to Raphaëlle Bellando, Jean-Paul Pollin, Camelia Turcu, participants at the 2013 INFER Annual Conference, as well as seminar participants at the University of Orléans for their comments.

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Appendix A

1.2 Appendix B

1.3 Appendix C

1.4 Appendix D

1.5 Appendix E

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Toader, O. Estimating the impact of higher capital requirements on the cost of equity: an empirical study of European banks. Int Econ Econ Policy 12, 411–436 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10368-014-0303-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10368-014-0303-x