PURPOSE

This study aims to determine the incidence, demography, pathologic nature, and clinical significance of ileitis in ulcerative colitis patients who underwent restorative proctocolectomy.

METHODS

A prospectively collected pouch database and the case notes of 100 consecutive patients who underwent restorative proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis, under the care of a single surgeon, between 1988 and 2003 were reviewed. The original proctocolectomy specimens and pouch biopsies were reexamined and regraded blind, using the current diagnostic criteria. Patients were divided into two groups, those who had ileitis and those who had not. The demographic, clinical, and pathologic characteristics and the incidence of pouchitis of both groups were compared.

RESULTS

Twenty-two patients had ileitis (22 percent). Compared with those with noninflamed ileum, patients with ileitis had a significantly shorter disease duration (P < 0.005), many of them presented or progressed to a fulminant state requiring acute surgical intervention (P < 0.01), had strong association with pancolitis and primary sclerosing cholangitis (P < 0.001), and had a higher incidence of subsequent development of pouchitis (P < 0.001). There was no correlation between the presence of ileitis and colitis severity.

CONCLUSIONS

Ileitis in ulcerative colitis is not rare and does influence the prognosis, and the term “backwash” is a misnomer. Ulcerative colitis with ileitis represents a distinct disease-specific subset of patients. Its true incidence and clinical significance can be determined only if detailed microscopic characterization of the terminal ileum is performed routinely in every patient with ulcerative colitis and the clinical outcome of these patients is audited prospectively.

Similar content being viewed by others

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a diffuse inflammatory condition of the mucous membrane which begins in the rectum and may extend proximally, in continuity, to involve a variable length of the colon. Extension of the inflammatory process to the terminal portion of the ileum in patients with UC is commonly known. Hale-White first reported this phenomenon in 1881.1 The original interpretation of this was that it represents a reaction to the reflux of colonic contents into the terminal ileum, which gave rise to the term backwash ileitis (BWI).1,2

In the first half of the 20th century BWI had been reported in as many as 39 percent of autopsy specimens when the disease involved the entire colon.3 In recent literature the frequency of BWI in the colectomy specimens of patients with pancolitis ranged from 10 percent to 20 percent.4–6 Thus, BWI is well described but the underlying pathophysiology is poorly understood and its clinical significance has not yet been fully examined. This study aims to determine the incidence, demography, pathologic nature, and clinical significance of ileitis in UC patients who underwent restorative proctocolectomy (RPC).

PATIENTS AND METHODS

A prospectively collected pouch database and the case notes of consecutive patients who underwent RPC for UC, performed by a single surgeon at York Hospital, between March 1988 and December 2003 were reviewed. The standard operation performed was a totally stapled RPC using a 15-cm, two-limbed, “J-shaped” ileal pouch. Operative maneuvers such as mucosal proctectomy, endoanal retraction, and anal eversion were avoided. The diagnosis of UC was established in all patients by standard clinical, endoscopic, radiologic, and histologic methods.

The pouch database was prospectively collected by a specialist nurse and was obtained by regular outpatient visits at three monthly intervals for the first year and annually thereafter. Patients also had open access to a dedicated nurse-led pouch clinic and a multidisciplinary consultant-led inflammatory bowel disease clinic.

The original histopathology reports were retrospectively reviewed. To ensure uniform and standardized reporting of the pathologic variables, the original proctocolectomy specimens and pouch biopsies were reexamined and regraded using the current diagnostic criteria,6–9 by an experienced gastrointestinal pathologist who was blinded to the previous pathology report and the clinical outcome.

The severity of colitis was graded as mild, moderate, or severe.7 The extent of colitis was determined by the most proximal microscopic localization of the inflammation and was divided into left (up to splenic flexure), substantial (proximal to splenic flexure but short of pancolitis), and pancolitis.7

BWI was defined histologically with evidence of acute mucosal inflammation involving a minimum of 3 cm of the terminal ileum in the absence of histologic features of Crohn's disease (Figs. 1 and 2). The protocol in our Pathology Department is to take a cut from the ileocecal valve, followed by a second ileal cut at 3 cm, and a final cut from the most proximal ileal margin if different. BWI was not confused with inflammation of the ileocecal valve, which is frequently encountered in pancolitis.

The histopathology was regraded in the excised ileum or RPC pouch biopsies obtained after surgery, based on the presence or absence of acute inflammation, chronic inflammation, villous atrophy, eosinophil infiltration, erosions, and ulcerations.6,9 The regraded histology results obtained after reexamination were compared with the original pathology reports. The regraded histology results were used in this study.

All patients underwent routine annual endoscopic pouch surveillance with a flexible endoscope. During surveillance, random biopsies were obtained from any residual columnar cuff, the pouch itself (upper, lower, anterior and posterior), and the prepouch ileum. In addition, targeted biopsies were taken from areas exhibiting active inflammation.

All patients with pouchitis had the diagnosis confirmed using a combination of clinical, endoscopic, and histologic criteria at least once.9,10 All patients with pouchitis had the diagnosis confirmed or retrospectively adjusted for using the Pouchitis Disease Activity Index at least once.10

Pouchitis was considered acute if symptoms responded promptly to a short course (two weeks or less) of standard antibiotic therapy (metronidazole or ciprofloxacin) and the duration of symptoms was less than four weeks, and it was considered chronic if active symptoms lasted continuously for more than four weeks despite full-dose standard therapy or required more than two weeks of therapy every month for three consecutive months to achieve symptomatic control.

Patients with elevated biochemical markers of cholestasis (alkaline phosphatase and γ-glutamyl transpeptidase) underwent endoscopic retrograde cholangiography to determine whether primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) was present.11

Analysis and Statistical Methods

Comparison within subgroups of UC patients who underwent RPC defined by the terminal ileum status was undertaken for demographic, clinical, and pathologic characteristics (Table 1) and the development of pouchitis. The same variables (Table 1) and the terminal ileum status were analyzed as possible factors associated with pouchitis. For categoric data chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test (if expected cell counts were less than 5) was used. Mann-Whitney U test or Student’s t -test was used for continuous parametric data as appropriate.

Three series of univariate analyses to determine the variables associated with acute and chronic pouchitis collectively and individually were performed. Potentially associated variables (P < 0.1) were then tested using a multivariate logistic regression analysis. The relative risk was described by the estimated odds ratio (OR) with a 95 percent confidence interval.

All statistical calculations were performed by an independent biostatistician using the statistical package for the social sciences program (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). All hypotheses were two-sided and P < 0.05 was accepted as a significant result.

RESULTS

Between 1988 and 2003 a total of 106 patients underwent RPC at our institution. Six patients had the operation for a non-UC indication and were excluded. Complete follow-up was achieved on all patients; the median length of follow-up was 72 months (range, 12-192 months). There were 43 females and 57 males with a median age of 37 years (range, 16-64 years).

The final diagnosis remained UC in 98 and changed to indeterminate colitis in 2. None of our patients had previous segmental colonic resection, and all patients had a minimum of 3 cm of the terminal ileum excised. Therefore, no pathologic data were missing and a standardized pathologic assessment was possible for all patients.

In the original pathology reports BWI was observed in 14 patients. On the subsequent pathologic reexamination BWI was observed in an additional 8 patients. Crohn’s disease was explicitly excluded in all patients with BWI.

The clinical and pathologic characteristics and the occurrence of pouchitis in the patients’ subgroups according to their terminal ileum status are shown in Tables 2 and 3.

Patients with BWI had significantly shorter disease duration (median of 2 years vs. 6 years, P < 0.005), were more likely to require urgent colectomy for fulminant colitis (41 percent vs. 15 percent, P < 0.01), and showed a tendency to be younger (median age of 33 vs. 40.5 years) at the time of UC diagnosis.

All patients with BWI had concomitant pancolitis. In the 22 patients with BWI, the appendix showed UC changes in only 8. In one patient with BWI a low-grade dysplasia of the terminal ileum was noted similar to that of the corresponding colon. There was no strong correlation between the presence of BWI and the severity of colitis (P = 0.285). Five patients had proven PSC; all were in the BWI group.

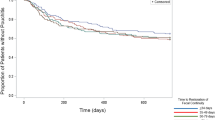

One or more episodes of pouchitis were observed in 33 patients. Seventeen patients experienced acute pouchitis, 2 had a single episode and 15 had multiple episodes. The other 16 patients had chronic pouchitis, many of whom needed long-term medical therapy. The results of the univariate analysis of possible pouchitis risk variables are presented in Tables 4 and 5.

The variables that significantly correlated with the occurrence of pouchitis (acute and chronic collectively) were the presence of BWI (P < 0.001), extent of colitis (P = 0.026), and PSC (P = 0.040). The same variables were associated with chronic pouchitis (P = < 0.001, 0.048, and 0.021, respectively). BWI was the only variable associated with acute pouchitis (P = 0.002).

To examine for potential confounding, we performed multivariate logistic regression analyses using those variables from univariate analyses with P < 0.1 (Tables 6 and 7). The only variable that was independently associated with subsequent development of acute and chronic pouchitis was the presence of BWI (P < 0.001). The relative risk of developing pouchitis in this group of patients was more than tenfold as high (OR, 11.3 vs. 1.1) as in patients with pancolitis but without BWI. The relative risk of developing chronic pouchitis in patients with BWI compared with patients with pancolitis but without BWI was even higher (OR, 27 vs. 0.7). The observed effect of colitis extent on the subsequent development of pouchitis was entirely dependent on the presence of BWI.

In a preliminary analysis of the surveillance pouch biopsies, a linear correlation was noted between the degree of inflammation, eosinophil infiltration, and villous atrophy of the terminal ileum and the degree of inflammation in the corresponding pouch mucosa. Thirty-six percent of patients with BWI had a marked degree of persistent subtotal or total villous atrophy of the pouch mucosa (Type C adaptive response)12 compared with 10 percent of those with noninflamed terminal ileum (P = 0.003). The detailed histologic correlation between the patients’ RPC pouch biopsies and their corresponding ileums and the time frame of these changes will be discussed in a separate publication.

DISCUSSION

This study shows that ileitis in UC patients undergoing RPC is not rare. It represents a distinct disease-specific subset of patients who are more likely to be younger, treatment-resistant, progress to fulminant stage, and require surgery early. They are also at a higher risk for the subsequent development of pouch-itis after RPC.

Ileitis was originally underreported in our series. In the eight patients in whom BWI was overlooked originally, cuts from the most proximal ileal margin were obtained and stained as per protocol but were not reported on.

A possible bias in the incidence of BWI might have been introduced by the fact that this study group is composed exclusively of patients who underwent RPC. This group of patients represents at most 20 percent to 30 percent of all patients with UC. Nevertheless, the incidence of BWI (22 percent) in this series is substantiated by similar figures reported in other studies.6,13–15

As the histologic examination was limited to the proctocolectomy specimens and only a small segment of the terminal ileum was available; it was not possible to assess the exact extent of ileal involvement. In autopsy studies the extent of ileal inflammation varied from 3 to 45 cm.1,16 For the same reason we do not know whether this involvement occurred early in the course of the colitis or whether it was a terminal event in the downhill progress of the disease.

We found no case of BWI without concomitant pancolitis, and the morphology of BWI was milder but similar to that of colitis. Patients with BWI required surgical intervention earlier than patients without BWI evidenced by a shorter duration of colitis before surgery; many of them progressed to or presented as fulminant colitis and required urgent colectomy. Whether the presence of BWI had influenced the natural course of UC or its response to therapy is unclear.

Patients with BWI are significantly more likely to develop pouchitis after RPC. The multivariate analyses confirmed that this association is independent of the extent of colitis. Therefore, the strong association of BWI with pouchitis cannot be attributed to the accompanying pancolitis, and the risk potential of BWI was presumably assigned to that of pancolitis in a number of patients in earlier studies which did not involve detailed assessment of the terminal ileum.

This finding is in contrast to that of a study by Gustavsson et al.,13 who examined the relation of radiographic and clinical presence of BWI with subsequent pouchitis. The authors concluded that the presence of BWI did not predispose the patient to later development of pouchitis. This result is at variance with our study; the difference could be explained in part by the present study’s use of blinded and strict histologic criteria to diagnose or exclude BWI and clinical, endoscopic, and histologic criteria to diagnose pouch-itis, as opposed to radiologic or clinical criteria for ileitis and clinical diagnosis of pouchitis with no histologic confirmation. Also, the follow-up of their study was much shorter than ours.

In support of our findings, Schmidt et al.6 compared the histopathology of the preoperative terminal ileum with pouch biopsies in the absence of clinical pouchitis and found that the presence of active inflammation, high eosinophil counts, and villous blunting in terminal ileal resection specimens were associated with significantly higher pouch biopsy active inflammation scores.

We found a strong association between the presence of BWI and PSC in UC patients. The multivariate analyses did not demonstrate an independent association between PSC and pouchitis. This is likely a result of the small number of patients with PSC in our study. PSC has previously been reported as an independent risk factor for pouchitis in larger studies,17 and recent findings also substantiate the link between PSC and BWI.18

Defects have been detected in the excretion and enterohepatic circulation of bile acids in patients with PSC.19 Bile acids are absorbed in the terminal ileum and may therefore play a role in the pathogenesis of BWI. Alternatively, the inflammatory process in the mucosa of patients with BWI may influence the enterohepatic circulations of bile acids, increasing the risk of PSC. It has been speculated that alterations in the metabolism of bile acids are involved in the pathogenesis of pouchitis.20

As a means of explaining the simultaneous presence of BWI, PSC, and pouchitis, one might speculate that some immunologic, metabolic, or genetic defect is the common underlying cause for all three pathologic changes.

Patients with previous BWI have marked degrees of villous atrophy (type C adaptive response). Setti-Carraro et al.12 reported that patients with type C adaptive response could be identified on histologic criteria within weeks of closure of ileostomy and were those exclusively at risk of chronic pouchitis. Merret et al.21 reported a linear correlation between the degree of villous atrophy and pouch mucosa permeability. Increased pouch mucosa permeability may lead to a reduction in barrier function and has been hypothesized in the pathogenesis of both pouchitis and extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease.21–23

The current treatment of pouchitis has mainly been empirical and directed at presumed bacterial or inflammatory mechanisms. The mainstays of therapy include antibiotics or anti-inflammatory agents. The results of this study, however, indicate that further research into the specific etiology and pathogenesis of this unique form of inflammation in UC could lead to more focused therapy of pouchitis. Patients with BWI should have detailed counseling on their higher risk of developing pouchitis, its effect on their quality of life, and the potential need for long-term therapy and the risk of failure. They should also undergo more regular postoperative surveillance and may be considered for early and more focused therapeutic strategies. It would be useful to investigate whether starting prophylactic therapy in patients with BWI before or immediately after pouch construction would prevent or decrease the incidence of pouchitis.

Classically the inflammation associated with UC is thought to involve only the colon and the presence of ileal inflammation is unexplained by the conventional understanding of the disease. Furthermore, if and when inflammation is noted in the small intestine, it is not thought to have any clinical or pathologic significance.13

In this study the presence of BWI did not correlate strongly with the severity of colitis, was associated with type C adaptive response, showed a strong association with PSC, and was an independent risk factor for the subsequent development of pouchitis. Furthermore, Heuschen et al.14 reported that the presence of BWI is strongly associated with colorectal carcinoma, and multiple tumor growth was significantly more frequent in patients with pancolitis and BWI than in patients with pancolitis without BWI in their series. Reports also have suggested that BWI has a premalignant potential, and several cases of de novo pouch, ileostomy, and proximal small bowel carcinomas in patients with BWI were reported.24–28 The ileum of one of our patients with BWI underwent dysplastic changes similar to that of the corresponding colon.

The findings of this study, supported by those studies mentioned above, suggest that the presence of ileitis in UC represents a primary involvement of the terminal ileum by the same mucosal inflammation as in the colon, refuting the “backwash” theory and suggesting that ileitis in UC is not necessarily a benign phenomenon.

It is unclear whether modification of the surgical technique, such as resecting more ileum in patients with terminal ileum inflammation, delaying the pouch procedure, or formation of the pouch with immediate prophylactic therapy, in such patients would affect the subsequent postoperative outcome. In our series we have taken biopsies above the pouch, at the top, middle, and bottom, and anterior and posterior of the pouch. The final topographic analysis of these data may help us understand if there is such a gradient of tissue susceptibility. Otherwise, a well-designed clinical trial will have to answer these questions.

Furthermore, by selecting a higher-risk group of UC patients, this study has implications for preoperative counseling, more intensive postoperative surveillance, and early and more specific preventative and therapeutic strategies aimed at a more targeted population.

The true incidence, natural history, and clinical significance of ileitis in patients with UC can be determined only if a routine and detailed microscopic characterization of the terminal ileum is performed in every patient with UC from presentation. Colonoscopy and retrograde ileoscopy is achievable in 85 percent to 90 percent of the patients.29–31 New modalities like MRI with enteroclysis,32 wireless capsule endoscopy,33 virtual enteroscopy,34 or confocal colonoscopy35 may also be useful. Identification of a molecular immunogenetic or immunophenotypic marker for this topographic variant of UC would be helpful.

CONCLUSIONS

This study demonstrates that there is a high frequency of ileitis in patients with UC who undergo RPC. Ileitis in UC may be a primary pathologic phenomenon and not a “backwash.” UC with ileitis represents a distinct disease-specific subset of patients who are more likely to be treatment-resistant, have a concomitant PSC, progress to a fulminant stage, and require urgent surgical intervention; they are also at a higher risk for the subsequent development of pouchitis after RPC.

More detailed microscopic characterization of the terminal ileum should be part of the routine histopathologic assessment of all patients with UC. UC patients with ileitis should have detailed counseling; their preoperative and postoperative progress should be audited closely and prospectively.

REFERENCES

FJ McCready JA Bargen MB Dockerty JM Waugh (1949) ArticleTitleInvolvement of the ileum in chronic ulcerative colitis N Engl J Med 240 119–27 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaH1M%2FgvFKlug%3D%3D Occurrence Handle18108072 Occurrence Handle10.1056/NEJM194901272400401

SL Saltzstein BF Rosenberg (1963) ArticleTitleUlcerative colitis of the ileum and regional enteritis of the colon: a comparative histopathologic study Am J Clin Pathol 40 610–23 Occurrence Handle14100664 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaF2c%2FlvVentA%3D%3D

JH Crandon TD Kinney IJ Walker (1944) ArticleTitlePerforation of the ileum following late ileostomy for ulcerative colitis N Engl J Med 230 419–21 Occurrence Handle10.1056/NEJM194404062301401

Morson BC, Dawson IM. Gastrointestinal pathology. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific, 1979:316-7

Riddell RH. Pathology of idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1995:120

CM Schmidt AJ Lazenby RJ Hendrickson JV Sitzmann (1998) ArticleTitlePreoperative terminal ileal and colonic resection histopathology predicts risk of pouchitis in patients after ileoanal pull-through procedure Ann Surg 227 654–65 Occurrence Handle9605657 Occurrence Handle10.1097/00000658-199805000-00006 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaK1c3ms1Kqtg%3D%3D

K Geboes R Riddel A Ost B Jensfelt T Persson R Lofberg (2000) ArticleTitleA reproducible grading scale for histological assessment of inflammation in ulcerative colitis Gut 47 404–9 Occurrence Handle10940279 Occurrence Handle10.1136/gut.47.3.404 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DC%2BD3cvjs1GitQ%3D%3D

HJ Silva ParticleDe CP Angelis ParticleDe N Soper MG Kettlewell NJ Mortensen DP Jewell (1991) ArticleTitleClinical and functional outcome after restorative proctocolectomy Br J Surg 78 1039–44 Occurrence Handle1933182

RL Moskowitz NA Shepherd RJ Nicholls (1986) ArticleTitleAn assessment of inflammation in the reservoir after restorative proctocolectomy with ileoanal reservoir Int J Colorectal Dis 1 167–74 Occurrence Handle3039030 Occurrence Handle10.1007/BF01648445 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaL2s3ot1Sgug%3D%3D

WJ Sandborn WJ Tremaine KP Batts JH Pemberton SF Phillips (1994) ArticleTitlePouchitis following ileal pouch-anal anastomosis: a Pouchitis Disease Activity Index Mayo Clin Proc 69 409–15 Occurrence Handle8170189 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaK2c3itl2gug%3D%3D

GR Haens ParticleDe BA Lashner SB Hanauer (1993) ArticleTitlePercholangitis and sclerosing cholangitis are risk factors for dysplasia and cancer in ulcerative colitis Am J Gastroenterol 88 1174–8 Occurrence Handle8338083

P Setti-Carraro IC Talbot RJ Nicholls (1994) ArticleTitleLong-term appraisal of the histological appearances of the ileal reservoir after restorative proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis Gut 35 1721–7 Occurrence Handle7829009 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaK2M7ivF2qug%3D%3D

S Gustavsson LH Weiland KA Kelly (1987) ArticleTitleRelationship of backwash ileitis to ileal pouchitis in patients after ileo-anal pull-through procedure Dis Colon Rectum 30 25–8 Occurrence Handle3026757 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaL2s7gsV2jsg%3D%3D

UA Heuschen U Hinz EH Allemeyer et al. (2001) ArticleTitleBackwash ileitis is strongly associated with colorectal carcinoma in ulcerative colitis Gatroenterology 120 841–7 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DC%2BD3M3hs1KjtQ%3D%3D Occurrence Handle10.1053/gast.2001.22434

RH Riddel H Goldman DF Ransohoff et al. (1983) ArticleTitleDysplasia in inflammatory bowel disease: standardized classification with provisional clinical applications Hum Pathol 14 931–68

B Counsell (1956) ArticleTitleLesions of the ileum associated with ulcerative colitis Br J Surg 44 276–90 Occurrence Handle13383154 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaG2s%2FivFenuw%3D%3D

C Penna R Dozois W Tremaine et al. (1996) ArticleTitlePouchitis after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for ulcerative colitis occurs with increased frequency in patients with associated primary sclerosing cholangitis Gut 38 234–9 Occurrence Handle8801203 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaK283ks1elsQ%3D%3D

GC Harewood EV Loftus WJ Tremaine WJ Sandborn (1999) ArticleTitle“PSC-IBD”: a unique form of inflammatory bowel disease associated with primary sclerosing cholangitis Gastroenterology 116 A732

V Balan NF Russo ParticleLa (1995) ArticleTitleHepatobiliary disease in inflammatory bowel disease Gastroenterol Clin North Am 24 647–67 Occurrence Handle8809241 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaK28vgsFWjsw%3D%3D

NF Breuer DS Rampton A Tammar et al. (1983) ArticleTitleEffect of colonic perfusion with sulphated and nonsulphated bile acids on mucosal structure and function in the rat Gastroenterology 84 969–77 Occurrence Handle6299874 Occurrence Handle1:CAS:528:DyaL3sXktVeksb4%3D

MN Merrett N Soper N Mortensen DP Jewell (1996) ArticleTitleIntestinal permeability in the ileal pouch Gut 39 226–30 Occurrence Handle8991861 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaK2s7jtFyksw%3D%3D

M DeVos C Cuvelier H Miclants E Veys F Barbier A Elewant (1989) ArticleTitleIleocolonoscopy in seronegative spondyloarthropathy Gastroenterology 96 339–44 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaL1M%2FptF2htw%3D%3D

AJ Morris CW Howden C Robertson et al. (1991) ArticleTitleIncreased intestinal permeability in ankylosing spondylitis-primary lesion or drug effect Gut 32 1470–2 Occurrence Handle1773950 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaK387ivVOlug%3D%3D

W Schlippert F Mitros K Schulze (1979) ArticleTitleMultiple adenocarcinomas and premalignant changes in “backwash” ileitis Am J Med 66 879–82 Occurrence Handle443263 Occurrence Handle10.1016/0002-9343(79)91146-X Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaE1M7osFWjtg%3D%3D

CH Brown RJ Diaz WM Michener (1964) ArticleTitleCarcinoma of the colon and ileum in chronic ulcerative colitis with reflux ileitis-report of a case of a sixteen-year-old boy Gastroenterology 47 306–12 Occurrence Handle14211953 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaF2M%2Fhs1entw%3D%3D

UA Heuschen G Heuschen F Autschbach EH Allemeyer C Herfarth (2001) ArticleTitleAdenocarcinoma in the ileal pouch: late risk of cancer after restorative proctocolectomy Int J Colorectal Dis 16 126–30 Occurrence Handle11355319 Occurrence Handle10.1007/s003840000276 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DC%2BD3M3mtlCnsQ%3D%3D

M Vieth M Grunewald C Niemeyer M Stolte (1998) ArticleTitleAdenocarcinoma in an ileal pouch after prior proctocolectomy for ulcerative pancolitis Virchow Arch 433 281–4 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaK1cvktVSluw%3D%3D

PL Roberts MC Veidenheimer S Cassidy ML Silverman (1989) ArticleTitleAdenocarcinoma arising in an ileostomy. Report of two cases and review of the literature Arch Surg 124 497–9 Occurrence Handle2539068 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaL1M7pt1ymtA%3D%3D

M Bruewer CF Krieglstein M Utech et al. (2003) ArticleTitleIs colonoscopy alone sufficient to screen for ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal carcinoma? World J Surg 27 611–5 Occurrence Handle12715233 Occurrence Handle10.1007/s00268-003-6639-y

VN Perisic D Filipovic (1988) ArticleTitleIleoscopy and its clinical role in the assessment of backwash ileitis in children with ulcerative pancolitis: Belgrade experience J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 7 146–8 Occurrence Handle3335979 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaL1c%2FptVamtg%3D%3D

SL Newman (1987) ArticleTitleIleoscopy, colonoscopy, and backwash ileitis in children with inflammatory bowel disease: quid pro quo? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 6 325–7 Occurrence Handle3430241 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DyaL1c7hvVShsQ%3D%3D

A Laghi O Borrelli P Paolantonio et al. (2003) ArticleTitleContrast enhanced magnetic resonance imaging of the terminal ileum in children with Crohn's disease Gut 52 393–7 Occurrence Handle12584222 Occurrence Handle10.1136/gut.52.3.393 Occurrence Handle1:STN:280:DC%2BD3s%2FntlCgug%3D%3D

AK Hara JA Leighton VK Sharma DE Fleischer (2004) ArticleTitleSmall bowel: preliminary comparison of capsule endoscopy with barium study and CT Radiology 230 260–5 Occurrence Handle14617764

DW Hommes SJ Deventer ParticleVan (2004) ArticleTitleEndoscopy in inflammatory bowel diseases Gastroenterology 126 1561–73 Occurrence Handle15168367 Occurrence Handle10.1053/j.gastro.2004.03.023

R Kiesslich J Burg M Veith et al. (2004) ArticleTitleConfocal laser endoscopy for diagnosing intraepithelial neoplasias and colorectal cancer in vivo Gastroenterology 127 706–13 Occurrence Handle15362025 Occurrence Handle10.1053/j.gastro.2004.06.050

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Mr. E. Grant, Head of the Department of Clinical Effectiveness, York Hospital, for his assistance with statistical analysis and Professor H. M. Zimaty, Director of the Gastroenterology Pathology Laboratory, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas, for reviewing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Reprints are not available.

About this article

Cite this article

Abdelrazeq, A., Wilson, T., Leitch, D. et al. Ileitis in Ulcerative Colitis: Is It a Backwash?. Dis Colon Rectum 48, 2038–2046 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10350-005-0160-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10350-005-0160-3