Abstract

Commercial trade is one of the leading threats to bears as they are targeted for trophies, food and medicines. While the threat from illegal trade and trafficking has been extensively studied in Asia, understanding of bear trade dynamics outside this region is limited. Poland is an end use destination for wildlife products such as trophies and wildlife-based traditional medicines. To gain an understanding of the bear trade in Poland, we conducted an analysis of (1) seizure data, (2) Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) trade data and (3) online surveys of Polish websites. We found that the trade of bears in Poland predominantly involves a demand for traditional bear-based medicines and, to a lesser extent, trophies. While trade in bear-based medicines and trophies is permissible with appropriate permits, illegal trade in such commodities is occurring in violation of CITES and European Union Wildlife Trade Regulations and in case of brown bear specimens—also national laws. This may possibly be due to a lack of public awareness regarding laws governing the import and export of bear parts and derivatives in which case education and awareness raising programmes might prove beneficial in eradicating trafficking of bear-based medicines and trophies. The use of bear bile for traditional medicine in Eastern Europe has not been previously documented and merits further research as to its scale, the source of bears used for these purposes and the potential impacts to bear populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Wild plants and animals are harvested around the globe for a variety of purposes, but most notably for commercial trade (Nijman 2010; Duckworth et al. 2012; Van Uhm 2016; D’Cruze et al. 2020; Morton et al. 2021). The trade in wildlife revolves around the demand for food, medicines, pets, entertainment, trophies, jewellery, clothing, luxury goods, ornamental items, charms or talismans (Nijman 2010; Alves et al. 2013; Auliya et al. 2016; Buscher and Ramutsindela 2016; Gaius 2018; Gomez 2021). These demands have resulted in a multibillion-dollar wildlife trade industry which has become a major threat to biodiversity, human health and economic security (TRAFFIC 2008; Van Uhm 2016; WAP 2020; Morton et al. 2021). An estimated 62% of birds, mammals and reptiles in trade show a decline in abundance in the wild (Morton et al. 2021). Based on the World Wildlife Trade Report released in November 2022, from 2011 to 2020, over 1.26 billion plants and 82 million animals and an additional 279 million kg of wildlife products were recorded in international trade (Secretariat CITES 2022). These volumes however only cover species listed in CITES that are traded internationally. These figures do not include domestic or illegal wildlife trade volumes. Discourse on the issue of unsustainable and illegal wildlife trade has intensified in recent years as we face a global biodiversity extinction crisis (Ceballos et al. 2010; Shivanna 2020). While there are numerous factors (e.g. deforestation, habitat loss and degradation) contributing to the extinction of species, Fukushima et al. (2020) reveal the pervasiveness of the global wildlife trade which encompasses species from almost all marine and terrestrial realms and habitats. Historically, wildlife has been harvested and hunted for subsistence, livelihood needs and trade (Milner-Gulland and Bennett 2003). But the human population is consistently expanding and intensifying the demand for natural resources. Over-hunting/harvesting is now rife in many parts of the world, and in some regions, widespread indiscriminate poaching for trade is fast becoming the main driver of species declines (Harrison 2011; Symes et al. 2018; Van Uhm 2016; Hughes et al. 2023).

Amongst the many species in peril are bears (Order: Carnivora, Family: Ursidae) with eight extant species in the world (Table 1). The demand for bears and their parts and derivatives is high and fuels both legal and black-market trade in the different species (Mills and Servheen 1994; Shepherd and Nijman 2007; Burgess et al. 2014; Shepherd et al. 2020; Gomez et al. 2021). They are killed for their gall bladder and bile which are highly coveted for use in traditional Asian medicines (Feng et al. 2009; Gomez et al. 2020). Their meat and paws are also considered delicacies in parts of the world, and their body parts (e.g. skins, skulls, claws, teeth) prized as trophies or talismans (Braden 2014; Gaius 2018; Shepherd et al. 2020). Live bears are captured for the pet trade, bear bile extracting facilities (otherwise known as bear farms) and wildlife entertainment industries (e.g. exhibitions, performances, bear baiting) (Gupta et al. 2007; D’Cruze et al. 2011; Livingstone et al. 2018). Such demands have led to the depletion of bear populations in some areas, particularly in Asia (Scotson 2012; Nijman et al. 2017; Crudge et al. 2018).

The illegal trade and trafficking of bears in Asia have been extensively studied and have revealed that these threats exist to bears in other parts of the world, e.g. Russia, the USA and New Zealand (Foley et al. 2011; Mills et al. 1995; Burgess et al. 2014). While targeted studies on the illegal trade of bears outside the Asian region are limited (Shepherd et al. 2020; Cassey et al. 2021), seizures of bear parts in Australia and New Zealand, countries with no native bear species, serve to highlight the far-reaching consequences commercial use has on bears (Cassey et al. 2021). Furthermore, an analysis of seizures in the Czech Republic revealed the international smuggling of bear parts and derivatives into the country involved countries and territories from as far away as Canada and Vietnam, to neighbouring Slovakia (Shepherd et al. 2020). Europe is an important destination market for wildlife (Kecse-Nagy et al. 2006; Van Uhm 2016; Altherr and Lameter 2020; Humane Society International 2021; Altherr et al. 2022). For example, the region is considered one of the biggest importers of wildlife trophies, including bears (Kecse-Nagy et al. 2006; Gaius 2018; Humane Society International 2021). Poland, in particular, was reported as the biggest importer of brown bear trophies in the European Union (EU) (Humane Society International 2021). An assessment of wildlife crime in Poland describes the country as mostly an end use destination for wildlife products and that the illegal market for traditional Asian medicines was growing (Paquel 2016). According to Duda (2018), one of the most frequently smuggled products of traditional Asian medicine into Poland was bear bile. Considering this, we have analysed the international trade of bears and their parts and derivatives in Poland to gain a deeper understanding of the country’s role in the trafficking of bear-based products and to raise awareness amongst enforcement agencies and other relevant stakeholders regarding appropriate mitigation measures that can reduce the illegal trade and exploitation of bears.

Methods

To assess the international illegal and legal trade of bears and their parts and derivatives in/into Poland, we conducted an analysis of (1) seizure data, (2) CITES trade data and (3) online surveys of Polish websites.

Seizure data

Seizure data involving bear parts and derivatives were obtained from the Polish Customs Service for the period 2000 to 2021. Polish Custom Service controls the borders of the territory with Ukraine, Belarus and Russia and focuses on the legality of imports and exports of goods. It should be noted that, during the period of time covered by this study, there were no seizures of bear products leaving Poland. Overwhelming majority of the seizures concern the imports of bear products into Poland, except in one incident, where Poland was a transit country. A “source country” is defined as the first known point of a trade route, a “transit country” is defined as a country which had functioned or was intended to function as both an importing and a re-exporting country in the trade route, and a “destination country” is defined as the last known or reported end point of a trade route.

From each record obtained, we extracted, where available, information pertaining to date of seizure, species of bear seized, commodity (body parts, bear bile derivatives, etc.), quantities of each commodity seized, purpose of hunting/trade (i.e. for consumption, pets and trophies) and origins (point of export) of seized items. Species identification was based on information extracted from seizure records obtained, and it is assumed to be accurate as further verification was not possible. Due to inherent biases in the way seizure data are reported, i.e. attributed to varying levels of law enforcement, reporting and recording practices, this dataset is interpreted with caution. It should be noted that the presented data set should not be assumed to encompass absolute trafficking volumes or scale of the bear trade in Poland given the inherently covert nature of the illegal wildlife trade.

CITES trade data

All bear species are listed on the CITES Appendix I or II and the EU Wildlife Trade Regulations (EU WTR) Annex A or B (Table 1), and therefore, all imports and exports of bear specimens and derivatives would require CITES permits which should be recorded in the CITES Trade Database (trade.cites.org), an open access database. Data on the international trade of bear species into and out of Poland were extracted from the CITES Trade Database in January 2023 using the search details in Table 2.

Online survey

A “snapshot” online survey of Polish auction sites, social media and advertising platforms was conducted to determine whether specimens of bears could be found for sale. This was conducted twice, once in January 2021 and once in November 2021. Google is a common search engine used for the online monitoring of wildlife trade (Hughes et al. 2021; Toomes et al. 2023), and we used this to search for current advertisements in local language with the following keywords: “bile”, “fat”, “skin”, “skull”, “trophy”, “fangs” and “claws”, in conjunction with the word differently inflected “bear”, “price”, “zloty” and “zl” (last two are Polish currency—full name and abbreviation). Data extracted from each advertisement included commodity for sale (parts, derivatives, etc.) and origin of item(s). Advertisements that did not display any intent of sale were left out of the data collection. No personal data about the sellers were collected, no interaction with sellers took place, and no products were purchased as part of this study. To avoid any inflation of numbers, care was taken to review every advertisement and eliminate all duplicates, including those that appeared with different dates.

Results

Seizure data

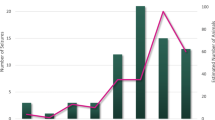

A total of 123 seizures involving bear parts and derivatives were obtained between 2000 and 2021. This encompassed 58 seizures of trophies (paws, skins, skulls, teeth) amounting to 75 items and 65 seizures of medicinal derivatives (bear fat, bear bile creams, ointments and powders, etc.) amounting to 5992 items (Table 3). The greatest number of seizures occurred in 2019 (n = 16 incidents) followed by 2015 and 2020 (both n = 10 incidents). But the largest seizures occurred in 2006 when 2580 vials of bear fat were confiscated by Polish customs which were in transit from Russia to Germany; in 2011, when 875 tubes of bear fat and bear bile imported from Ukraine were confiscated; and in 2015, when 2000 capsules with bear fat imported from Ukraine were confiscated.

The species of bear seized were reported in 55 incidents, the most predominant species being the brown bear (35.8% of seizures) followed by the American black bear (9.7% of seizures). The polar bear was reported seized in one incident. In remaining seizures (53.7%), species seized were only reported to family level, Ursidae, which is attributed to the fact that these seizures were mostly (89.4%) of medicinal products.

There was a visible change in the type of contraband being transported over the years. In the beginning of the study period, seizures were mostly of different types of hunting trophies. In 2006, a notable shift from trophies to medicinal products was observed and subsequently dominated in terms of commodity seized (Fig. 1).

At least eight countries were implicated in the illegal trafficking of bear parts and derivatives into Poland (Fig. 2). Most of the seizures concerned exports from Ukraine (52%) and Russia (19.5%) and comprised mostly trophy items from Russia and traditional medicinal products from Ukraine. Fewer seizures concerned items exported from the USA (6.5% of all seizures), Canada (5.7% of all seizures) and Belarus (4.9% of all seizures).

The number of legal import records of bears and parts into Poland from 2000 to 2021 and countries of export: AM, Armenia; BY, Belarus; CA, Canada; DK, Denmark; EE, Estonia; EG, Egypt; GL, Greenland; HR, Croatia; NO, Norway; RO, Romania; RU, Russia; SK, Slovakia; UA, Ukraine; USA, United States of America; XX, unknown. This information has been extracted from the CITES Trade Database (https://trade.cites.org/)

CITES trade data

According to the CITES Trade Database, between 2000 and 2021, there were 283 records relating to imports of bears and their parts and derivatives to Poland, involving American black bear (141 records), brown bear (97 records) and the polar bear (45 records). The majority of imports were from Canada (60.4%) followed by Russia (19%) and the USA (10.2%) (Fig. 2; Table 4). Exports from other countries were occasional—these were the following: Armenia, Belarus, Croatia, Denmark, Egypt, Estonia, Greenland, Norway, Romania, Slovakia and Ukraine (Fig. 2).

Most imports were bear trophies (95%) such as whole bodies or their parts (bones, claws, skins, skulls and teeth) as well as garments and carvings, amounting to between 869 items (importer reported quantities) and 1223 items (exporter reported quantities) (Table 4). Other imports were of meat (3 records—28.3 kg), live bears (3 records—19 animals), derivatives (3 records—20 items + 12,000 mL) and specimens (4 records—23 items based on importer reported quantities and 8 items based on exporter reported quantities) (Table 4). Derivatives generally refer to processed wildlife parts such as medicines, while specimens are generally samples such as blood or hair that are sent for lab analysis. For all four records of specimens imported, the purpose code reported was “S”, meaning the transaction was scientific in nature. The majority of items were obtained from wild bears (94%), with the exception of live bears which were reported as captive-bred (source code C) and 12 items which were reported as being seized (source code I). Most of the goods with code I were different types of hunting trophies (e.g. bodies, skins, skulls, teeth) mainly from Russia and the USA followed by single records from Canada and Belarus, respectively. The other items with source code I included two exports of bear derivatives from Egypt and Ukraine.

In the same timeframe, there were 18 export records of bears and their parts and derivatives from Poland involving the brown bear (15 records), followed by the American black bear (2 records) and the spectacled bear (1 record). Majority of exports were of live bears (8 records) that were mostly from captive-bred sources (6 records) (Table 5). In one record, the source was reported as wild, and in another, the source was unknown. Live bears were exported primarily under the purpose code of circus/travelling exhibition (5 records) and zoos (2 records) and in one case for reintroduction into the wild (purpose code N). They were exported to Romania (2 records), Russia (2 records), Switzerland (2 records), Great Britain (1 record) and Uzbekistan (1 record). Of these eight records, five were re-exports from Russia (4 records) and Germany (1 records).

Hunting trophies (5 records) were exported to Norway (2 records) and the USA (2 records). These were all re-exports from Croatia (2 records), Canada (1 record) and the USA (1 records).

The only other items exported were samples (6 records), mostly hair, to Canada for scientific purposes.

Online trade

There were at least 12 Polish-language platforms with single offers openly selling products made of bear derivatives. This comprised eight online shops, two social media platforms, one online auction service and one advertisement service (Table S1). One of the shops had a Ukrainian domain, and prices were given in Ukrainian currency (hryvnia) or USD or EUR, but the description and web page were in Polish, and therefore, it was included in the analysis.

All products found for sale were traditional medicine. At least six different types of products were found, i.e. bear fat in 100-, 220- and 250-mL vials and bear bile balms in 100- or 125-mL tubes (Fig. S1). The most popular product was Radiculin, a balm produced in Russia, which in addition to bear bile contained also extract of the medicinal leech (CITES App. II, EU WTR Ann. B). The average price for Radiculin was 37 PLN (~ 8 USD) per 100-mL tube.

Discussion

This study provides the first account of the trade of bears in Poland. It reveals a demand for bear-based medicines and, to a lesser extent, trophies. While trade in bear-based medicines and trophies is permissible with appropriate permits, illegal trade in such commodities is occurring in violation of the CITES Convention and EU WTR and in case of brown bear specimens—also national laws.

Traditional medicine trade

Based on seizure data, a notable increase involving the confiscation of bear-based medicines in Poland was observed from 2006 onwards. Bear-based medicines were also the only commodity observed for sale online. This supports the findings of Paquel (2016) regarding a growing illegal market for traditional medicines in Poland. The harvesting of bears for use in traditional Asian medicine has been in practice for thousands of years, and its use is relatively well known and studied (Feng et al. 2009). Asians are considered the biggest consumers of bear bile medicines, and it is generally presumed that migrant Asian communities are responsible for the consumption of such products outside of Asia (Mills and Servheen 1991; WAP 2018; Shepherd et al. 2020). While there is a very minor Asian migrant population in Poland (GUS 2020), our data suggests an Eastern European market exists for bear-based medicines. The rise in seizures involving bear derivatives in Poland correlates with the increasing number of Eastern European migrants (mainly Ukrainians) to the country (GUS 2020). The rapid increase in the number of Ukrainians residing in Poland was first observed in 2014 (Górny et al. 2018; Wendt et al. 2018), after Russia invaded and annexed the Crimean Peninsula. In 2022, before the full-scale war in Ukraine had started, it was estimated that there were approximately 1.3 million economically active Ukrainian citizens in Poland (Duszczyk and Kaczmarczyk 2022). Bear-based medicines—mainly bear fat and gall—are known to be used in Ukraine. According to Sõukand and Pieroni (2016), bear fat is consumed to treat tuberculosis, or mixed with vodka or rubbed on the chest to treat a cold.

A significant proportion of bear derivatives seized in Poland were imports from Ukraine followed by imports from Russia. However, it appears that the country of origin for all items was Russia based on the labels of items seized which were in Russian. Russia has the biggest brown bear population in the world—believed to exceed 100,000 (McLellan et al. 2017), whereas the population of brown bears in Ukraine is small and restricted to the Carpathian regions (Gashchak et al. 2016). So, it is not surprising that Russia is the country of origin of seized bear parts. Furthermore, in parts of Russia, there is a popular demand for bear fat and bile which is used in traditional health care and aesthetic medicine (WWF 2020), and this is likely to have influenced consumers in neighbouring countries such as Ukraine, i.e. the border traffic between these two countries was intense prior to the Russian invasion in 2022.

Russia is a known source of bear parts in trade globally (Burgess et al. 2014; Gomez et al. 2023). While it is legal to hunt and trade in bear parts and derivatives in Russia, the legal export of such products requires CITES export permits which were absent, thus rendering the import of these products into Poland illegal. Furthermore, based on CITES trade data, there are no imports of bear-based medicines into Poland. As such, bear derivatives of Russian origin found for sale on Polish websites are also likely illegally imported. Another aspect that needs to be considered is whether the origins of these products are legal, as poaching of bears still occurs in Russia—in some regions of the Russian Far East, illegal harvest exceeds several times the legal harvest (Seryodkin 2006). It is possible that in many cases, people buy these products for personal consumption and are unaware of the illegality associated with bringing these products into Poland. Similarly, in many situations, citizens of Eastern Europe who bring these products into Poland without proper CITES permits may not realize that these products are subject to restrictions, especially since in their countries of origin trade, it is common and in accordance with applicable law. Potential solutions to mitigate the illegal trafficking of bear-based medicines may lie in education and awareness programmes regarding the laws governing the trade in bears and their parts and derivatives, i.e. people can only comply with laws if they know about them (Paudel et al. 2020). In-depth research on the utilisation of bear-based medicines in Eastern Europe is required to assess the scale, source of bears used for these purposes and potential impacts to bear populations.

The brown bear is a strictly protected species in Poland under the Nature Conservation Act, 2004. Therefore, many restrictions apply to this species, e.g. any specimens of this species cannot be transported in the country or across state borders, sold, offered for sale or owned. Non-native species of bears are not protected by Polish national legislation, but because all Ursidae family members are included in the EU WTR Annex A or B, commercial activities involving bears are prohibited unless appropriate EU certificate is issued (in case of Annex A species) or it can be proven that the specimen was acquired or introduced into EU in accordance with the legislation in force for the conservation of wild fauna (in case of Annex B species). There is no specific national legislation in Poland regulating online trade in wildlife, and this presents a loophole that needs to be amended. General prohibition of sale or offers of sale of specimens of protected species includes online trading. However, usually it is difficult to assess if the Internet offer of sale is legal or not. Therefore, some of the e-commerce platforms have introduced their own regulatory provisions to deal with this problem. According to the rules of the biggest internet auction service in Poland—Allegro (www.allegro.pl), it is prohibited to offer sale of any specimens of animal species covered by EU WTR Annexes A–D. Although the proper implementation of this provision is seriously enforced by the platform, there are cases where advertisements of protected animal specimens appear for a short time on the portal. The lack of appropriate legislative provisions on the national level and a coherent approach to this problem causes sellers to move to platforms that do not have internal regulations limiting trade in specimens of protected species.

Trophy hunting trade

Bear trophies accounted for the majority of legal imports and to a lesser extent illegal imports into Poland. Both CITES and seizure records showed a decreasing number of records involving bear trophies over the study period. That said, a recent study on the EU’s role in the trade of wildlife trophies, Poland was ranked in the top 10 EU countries of significance and showed an overall increase in trophy imports encompassing at least 36 CITES listed species between 2014 and 2018 (Humane Society International 2021). The top three species imported were brown bears, African lions and American black bears. Poland was also noted as the top EU importer of brown bear trophies which were predominantly from Russia (Humane Society International 2021).

Our study shows that Canada, Russia and the USA were the biggest exporters of bear trophies to Poland both legally and illegally. All three countries have been shown to be a key source of illegal bear parts in trade (Foley et al. 2011; Braden 2014; Burgess et al. 2014; IFAW 2016; Gaius 2018; Shepherd et al. 2020). These countries allow the hunting of bears with a permit and the export of bear trophies with a CITES permit. Nevertheless, illegal hunting and export of bear trophies persist from these countries (Foley et al. 2011; Braden 2014; Burgess et al. 2014; IFAW 2016; Gaius 2018; Shepherd et al. 2020). Possible reasons for this include illegal harvest, poaching for commercial trade, invalid/lack of hunting permits, avoidance of permit fees or import duties, or ignorance of legal requirements (Gaius 2018; MNR 2020; Skidmore 2021). For example, despite an EU-implemented ban on the imports of brown bear trophies from British Columbia (Canada) due to unsustainable hunting pressure from EU residents, illegal imports still occurred (Gaius 2018). In March 2020, 10 people (3 Canadian and 7 US nationals) were convicted for illegally killing black bears in Canada including falsifying records and illegally transporting hides to the USA for taxidermy (MNR 2020). In Russia, Skidmore (2021) revealed how hunting permits can be purchased for any legal game though there were no checks in place to make sure the permit correlated with the species hunted.

Trophy hunting is a multibillion-dollar global commercial industry that is plagued by corruption and poor management raising conservation concerns for threatened species (Eliason 2012; Bird 2018; Gaius 2018; Dellinger 2019; Heinrich et al. 2022). This study also shows trophy hunting leaves room for fraudulent activities such as illegal trade. Hellinx and Wouters (2020) further note the challenges in regulating trophy hunting under the current national and international legal framework governing the industry. As such, we strongly recommend the authorities in Poland increase their vigilance and scrutinize all imports of wildlife declared as trophies in the future.

Data limitations

There are several limitations to our study including the restrictive nature of using seizure data in understanding the magnitude of trade or even the impacts such trade has on wild populations due to the fact that seizures only encompass incidents of trafficking that have been detected. Nevertheless, it provides a baseline for the illegal bear trade in Poland which has not been previously captured. The use of the CITES Trade Database is also challenging (D’Cruze and MacDonald 2016; Robinson and Sinovas 2018), as reported trade levels by importing and exporting countries often differ significantly. This is due to the fact that some countries report based on the actual imported or exported quantities while others report trade based on permits issued which does not always translate to the actual number of animals included in a transaction (Foster et al. 2016; Robinson and Sinovas 2018). Furthermore, while CITES trade data does technically refer to legal trade, studies have revealed weaknesses in the CITES permitting system that enables the laundering of wild animals falsely declared as captive-bred (Nijman and Shepherd 2015; Poole and Shepherd 2017; Outhwaite 2020; Janssen and Gomez 2021). Similarly, it is impossible to know the authenticity of bear products for sale online from pictures or description provided by sellers alone or quantities that are sold. For this study, we assumed that the products advertised were genuine but acknowledge that this may not always be true.

Conclusion

Poland has an active trade in bear parts and derivatives which revolves around the domestic demand for trophies and traditional medicines. Trade is occurring both legally and illegally highlighting a need for greater monitoring and regulation. In particular, the demand for bear-based traditional medicines appears to be growing and is resulting in the illegal trafficking of such products from Russia and Ukraine into Poland. To mitigate the threat of illegal trade and potential poaching of bears in neighbouring countries to meet demand for bear-based medicines, greater research into the source of bears used for this purpose and scale of use is needed to ensure that wild bear populations are not being negatively impacted. Furthermore, enforcement of regulations regarding trade in bear-based medicines is warranted to ensure the required permits for and legal sourcing of such products are taking place. This includes the sale of these products on online platforms which provide consumers easy access to wildlife products regardless of illegality. Improved regulation and enforcement as well as enhanced scrutiny of online wildlife traders are needed to ensure that the sourcing, advertising and sale of wildlife products are occurring legally. Educating consumers on the laws governing the use, trade and cross-border movement of bear-based medicines will also be essential in reducing illegal trade of bear parts and derivatives into Poland, as will the enforcement of penalties afforded under the law for transgressions. Similarly, the illegal trade in hunting trophies reveals a crucial need for more stringent monitoring, regulation and enforcement of the industry especially since illegal exploitation persists in most if not all places that permit hunting wildlife for sport, e.g. Africa, Canada, Europe and USA (Gaius 2018; IFAW 2016).

References

Altherr S, Lameter K (2020) The rush for the rare: reptiles and amphibians in the European pet trade. Animals 10(11):2085

Altherr S, Silvestre ID, Swabe J (2022) Stolen wildlife IV: the EU – a destination market for wildlife traffickers. Pro Wildlife, IFAW, HIS Europe (eds.); Munich (Germany), The Hague (Netherlands), Brussels (Belgium)

Alves RRN, Vieira WLS, Santana GG, Vieira KS, Montenegro PFGP (2013) Herpetofauna used in traditional folk medicine: conservation implications. In: Animals in Traditional Folk Medicine. Springer 109–133

Auliya M, García-Moreno J, Schmidt BR, Schmeller DS, Hoogmoed MS, Fisher MC, Pasmans F, Henle K, Bickford D, Martel A (2016) The global amphibian trade flows through Europe: the need for enforcing and improving legislation. Biodivers Conserv 25:2581–2595

Bird M (2018) Stolen trophies: hunting in Africa perpetuates neo-colonial attitudes and is an ineffective conservation tool. Journal of Integrative Research and Reflection 1:37–46

Braden K (2014) Illegal recreational hunting in Russia: the role of social norms and elite violators. Eurasian Geogr Econ 55(5):457–490. https://doi.org/10.1080/15387216.2015.1020320

Burgess EA, Stoner SS, Foley KE (2014) Bring to bear: an analysis of seizures across Asia (2000 - 2011). TRAFFIC, Petaling Jaya, Selangor

Buscher B, Ramutsindela M (2016) Green violence: rhino poaching and the war to save Southern Africa’s peace parks. Afr Aff 115(458):1–22

Cassey P, Gomez L, Heinrich S, García-Díaz P, Stoner S, Shepherd CR (2021) Bearing all down under: the role of Australasian countries in the illegal bear trade. Pac Conserv Biol 28(6):472–480

Ceballos G, García A , Ehrlich PR (2010) The sixth extinction crisis: loss of animal populations and species. J Cosmol 8:31

Crudge B, Nguyen T, Cao TT (2020) The challenges and conservation implications of bear bile farming in Viet Nam. Oryx 54(2):252–259

D’Cruze N, Macdonald D (2016) A review of global trends in CITES live wildlife confiscations. Nature Conservation 15: 47–63. https://doi.org/10.3897/natureconservation.15.10005

D’Cruze N, Sarma UK, Mookerjee A, Singh B, Louis J, Mahapatra RP, Jaiswal VP, Roy TK, Kumari I, Menon V (2011) Dancing bears in India: a sloth bear status report. Ursus 22(2):99–105

D’Cruze N, Green J, Elwin A, Schmidt-Burbach J (2020) Trading tactics: time to rethink the global trade in wildlife. Animals 10(12):2456

Dellinger M (2019) Trophy hunting-a relic of the past. J Envtl L Litig 34:25

Duckworth JW, Batters G, Belant JL, Bennett EL, Brunner J, Burton J et al (2012) Why South-East Asia should be the world’s priority for averting imminent species extinctions, and a call to join a developing cross-institutional programme to tackle this urgent issue. SAPIENS 5:77–95

Duda M (2018) Cites crimes in Poland–causes, manifestations, prevention. Kriminalističke teme–Časopis za kriminalistiku, kriminologiju i sigurnosne studije 18(5–6):95–103

Duszczyk M, Kaczmarczyk P (2022) The war in Ukraine and migration to Poland: outlook and challenges. Intereconomics 57(3):164–170

Eliason SL (2012) Trophy poaching: a routine activities perspective. Deviant Behav 33(1):72–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2010.5482

Feng Y, Siu K, Wang N, Ng KM, Tsao SW, Nagamatsu T, Tong Y (2009) Bear bile: dilemma of traditional medicinal use and animal protection. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed 5(2). https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-4269-5-2

Foley KE, Stengel CJ, Shepherd CR (2011) Pills, powders, vials and flakes: the bear bile trade in Asia. TRAFFIC Southeast Asia, Petaling Jaya, Selangor

Foster S, Wiswedel S, Vincent A (2016) Opportunities and challenges for analysis of wildlife trade using CITES data–seahorses as a case study. Aquat Conserv Mar Freshwat Ecosyst 26(1):154–172

Fukushima CS, Mammola S, Cardoso P (2020) Global wildlife trade permeates the Tree of Life. Biol Cons 247:108503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108503

Gaius J (2018) Grizzly trophies in Europe: are B.C. grizzly bear parts being unlawfully imported into the EU? David Suzuki Foundation (14 May 2020). https://davidsuzuki.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Grizzly-Trophies-in-Europe-DSF-report-July2018-final.pdf

Gashchak S, Gulyaichenko Y, Beresford NA, Wood MD (2016) Brown bear (Ursus arctos L.) in the Chornobyl exclusion zone. Proceedings of the Theriological School 14(2016):71–84. https://doi.org/10.15407/ptt2016.14.071

Gomez L (2021) The illegal hunting and exploitation of porcupines for meat and medicine in Indonesia. Nature Conservation 43:109

Gomez L, Shepherd CR, Khoo MS (2020) Illegal trade of sun bear parts in the Malaysian states of Sabah and Sarawak. Endanger Species Res 41:279–287. https://doi.org/10.3354/esr01028

Gomez L, Wright B, Shepherd CR, Joseph T (2021) An analysis of the illegal bear trade in India. Global Ecology and Conservation 27:e01552

Gomez L, Toropov P, Shepherd CR (2023) Bears in the Russian Far East illegally exploited for meat, medicine and trophies. Tropical Conservation Science 16:19400829231191060

Górny A, Kaczmarczyk P, Szulecka M, Bitner M, Okólski M, Siedlecka U, Stefańczyk A (2018) Imigranci w Polsce w kontekście uproszczonej procedury zatrudniania cudzoziemców. Raport z badań. Warszawa: WISE Europa i Ośrodek Badań nad Migracjami UW. https://www.migracje.uw.edu.pl/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/raport-power.pdf. Accessed 9 Mar 2023

Gupta BK, Singh R, Satyanarayan K, Seshamani G (2007) Trade in bears and their parts in India: threats to conservation of bears. In: Williamson, D. (Ed)., Proceedings of the Fourth International Symposium on the Trade in Bear Parts. TRAFFIC East Asia-Japan

GUS (2020) Sytuacja demograficzna Polski do 2019 r. Migracje zagraniczne ludności w latach 2000–2019. Demographic situation in Poland up to 2019. International migration of population in 2000–2019. Główny Urząd Statystyczny Statistics Poland https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/ludnosc/migracje-zagraniczne-ludnosci/sytuacja-demograficzna-polski-do-roku-2019-migracje-zagraniczne-ludnosci,16,1.html. Accessed 9 Mar 2023

Harrison RD (2011) Emptying the forest: hunting and the extirpation of wildlife from tropical nature reserves. Bioscience 61(11):919–924

Heinrich S, Gomez L, Green J, de Waal L, Jakins C, D’Cruze N (2022) The extent and nature of the commercial captive lion industry in the Free State province, South Africa. Nat Conserv 50:203–225

Hellinx E, Wouters J (2020) An international lawyer’s field guide to trophy hunting. J Int Wildl Law Policy 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/13880292.2020.1768

Hughes AC, Marshall BM, Strine CT (2021) Gaps in global wildlife trade monitoring leave amphibians vulnerable. Elife 10:e70086

Hughes LJ, Morton O, Scheffers BR, Edwards DP (2023) The ecological drivers and consequences of wildlife trade. Biol Rev 98(3):775–791

Humane Society International (2021) Trophy hunting by the numbers: the European Union’s role in the global trophy hunting. https://www.hsi.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Trophy-hunting-numbers-eu-report.pdf. Accessed 9 Feb 2023

IFAW (2016) Killing for trophies: an analysis of global hunting trade. International Fund for Animal Welfare, USA

Janssen J, Gomez L (2021) An examination of the import of live reptiles from Indonesia by the United States from 2000 to 2015. J Nat Conserv 59:125949

Kecse-Nagy K, Papp D, Knapp A, von Meibom S (2006) Wildlife trade in Central and Eastern Europe. A review of CITES implementation in 15 countries. TRAFFIC Europe report, Budapest, Hungary. https://www.traffic.org/site/assets/files/10072/wildlife-trade-in-central-and-eastern-europe.pdf

Livingstone E, Gomez L, Bouhuys J (2018) A review of bear farming and bear trade in Lao People’s Democratic Republic. Global Ecology and Conservation 13:e00380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2018.e00380

McLellan BN, Proctor MF, Huber D, Michel S (2017) Ursus arctos (amended version of 2017 assessment). The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2017:e.T41688A121229971 https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-3.RLTS.T41688A121229971.en. Accessed 25 Mar 2023

Mills JA, Chan S, Ishihara A (1995) The bear facts: the East Asian market for bear gall bladder. TRAFFIC International, Cambridge, UK

Mills JA, Servheen C (1991) The Asian trade in bears and bear parts. World Wildlife Fund Inc, USA

Mills J, Servheen C (1994) The Asian trade in bears and bear parts: impacts and conservation recommendations. Bears: Their Biology and Management 1:161–7

Milner-Gulland EJ, Bennett EL (2003) Wild meat: the bigger picture. Trends Ecol Evol 18(7):351–357

MNR (2020) Illegal hunts result in lifetime hunting-licence suspensions and almost $60,000 in fines. https://mnrwatch.com/illegal-hunts-result-in-lifetime-hunting-licence-suspensions-and-almost-60000-in-fines/. Accessed 24 Mar 2021

Morton O, Scheffers BR, Haugaasen T, Edwards DP (2021) Impacts of wildlife trade on terrestrial biodiversity. Nature, Ecology and Evolution 5:540–548. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-021-01399-y

Nijman V (2010) An overview of international wildlife trade from Southeast Asia. Biodivers Conserv 19(4):1101–1114

Nijman V, Oo H, Shwe NM (2017) Assessing the illegal bear trade in Myanmar through conversations with poachers: topology, perceptions and trade links to China. Hum Dimens Wildl. https://doi.org/10.1080/10871209.2017.1263768

Nijman V, Shepherd CR (2015) Trade of ‘captive-bred’ birds from the Solomon Islands: a closer look at the global trade in hornbills. Malay Nat J 67(2):260–266

Outhwaite W (2020) Addressing corruption in CITES documentation processes. Available from https://www.traffic.org/site/assets/files/12675/topic-brief-addressing-corruption-in-cites-documentation-processes.pdf. Accessed 6 Mar 2020

Paudel K, Potter GR, Phelps J (2020) Conservation enforcement: insights from people incarcerated for wildlife crimes in Nepal. Conservation Science and Practice 2(2):e137

Paquel K (2016) Wildlife crime in Poland. Policy Department A: Economic and Scientific Policy, European Parliament, European Union, 2016. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/IDAN/2016/578960/IPOL_IDA(2016)578960_EN.pdf

Poole CM, Shepherd CR (2017) Shades of grey: the legal trade in CITES-listed birds in Singapore, notably the globally threatened African grey parrot Psittacus erithacus. Oryx 51(3):411–417

Robinson JE, Sinovas P (2018) Challenges of analyzing the global trade in CITES-listed wildlife. Conserv Biol 32(5):1203–1206

Scotson L (2012) Status of Asiatic black bears and sun bears in Xe Pian National Protected Area, Lao PDR. Int Bear News 2012:21(1)

Secretariat CITES (2022) World wildlife trade report 2022. Switzerland, Geneva

Seryodkin I (2006) The biology and conservation status of brown bears in the Russian Far East. Understanding Asian bears to secure their future. Japan Bear Network, Ibaraki, Japan

Shepherd CR, Kufnerová J, Cajthaml T, Frouzová J, Gomez L (2020) Bear trade in the Czech Republic: an analysis of legal and illegal international trade from 2005 to 2020. Eur J Wildl Res 66(6):1–10

Shepherd CR, Nijman V (2007) The trade in bear parts from Myanmar: an illustration of the ineffectiveness of enforcement of international wildlife trade regulations. Biodiversity Conservation 17:35–42

Shivanna KR (2020) The sixth mass extinction crisis and its impact on biodiversity and human welfare. Resonance 25(1):93–109

Skidmore A (2021) Uncovering the nuances of criminal motivations and modus operandi in the Russian Far East: a wildlife crime case study. Methodological Innovations 14(2):20597991211022016

Sõukand R, Pieroni A (2016) The importance of a border: medical, veterinary, and wild food ethnobotany of the Hutsuls living on the Romanian and Ukrainian sides of Bukovina. J Ethnopharmacol 185:17–40

Symes WS, Edwards DP, Miettinen J, Rheindt FE, Carrasco LR (2018) Combined impacts of deforestation and wildlife trade on tropical biodiversity are severely underestimated. Nat Commun 9(1):4052

Toomes A, Moncayo S, Stringham OC, Lassaline C, Wood L, Millington M, Drake C, Jense C, Allen A, Hill KG, García-Díaz P (2023) A snapshot of online wildlife trade: Australian e-commerce trade of native and non-native pets. Biol Cons 282:110040

TRAFFIC (2008) What’s driving the wildlife trade? A review of expert opinion on economic and social drivers of the wildlife trade and trade control efforts in Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao PDR and Vietnam. East Asia and Pacific Region Sustainable Development Discussion Papers. East Asia and Pacific Region Sustainable Development Department, World Bank, Washington, DC

Van Uhm D (2016) Illegal wildlife trade to the EU and harms to the world. In Environmental Crime in Transnational Context (pp. 59–82). Routledge

WAP (2018) Unbearable: the international bear bile trade. Wordl Animal Protection. https://www.worldanimalprotection.us/sites/default/files/media/us_files/unbearable-the-international-bear-bile-trade-sept-2018.pdf

WAP (2020) Cruel cures: the industry behind bear bile production and how to end it. World Animal Protection. https://www.dropbox.com/s/2kzpdkfjn4vh347/Bear%20Bile%20Re-port_Cruel%20Cures_FINAL_compressed.pdf?dl=0

Wendt JA, Lewandowska I, Wiskulski T (2018) Migranci ukraińscy w Polsce w latach 2014–2017. Scientific Papers of Silesian University of Technology 126:223–236

WWF (2020) Wildlife trade in the Russian Federation. WWF Russia, Moscow

Acknowledgements

We thank the Polish Customs Service for sharing seizure data with us and Karine and Anna Hauser for their continuous support and funds that makes our work on bears possible. We also thank Loretta Shepherd for helpful comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript.

Funding

This project was funded by a private donor.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Project funding was secured by Chris R. Shepherd. Data collection was done by Borys Kala, and data analysis were performed by Lalita Gomez and Borys Kala. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Lalita Gomez and all authors subsequently contributed to writing, editing and review of all versions of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gomez, L., Kala, B. & Shepherd, C.R. Bear trade in Poland: an analysis of legal and illegal international trade from 2000 to 2021. Eur J Wildl Res 69, 106 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10344-023-01737-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10344-023-01737-4