Abstract

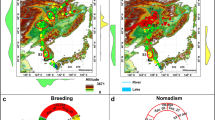

Understanding space use and how it changes over time is critical in animal ecology. The subadult period is the transition from juvenile to adult. Adults and subadults have different biological requirements in summer, resulting in differential space use patterns. We tagged 66 White-naped Cranes (Antigone vipio) in eastern Mongolia, including 22 adults and 44 hatch-year juveniles, using GPS/GSM trackers from July to August, 2017–2019. The objectives are to characterize and compare space use, especially home ranges of adults and subadults, of White-naped Cranes and to investigate patterns in summer. We split the entire summering period into 6 stages (pre-incubation, incubation/nestling, pre-molting, molting/post-molting, post-fledging, moving to another area before autumn migration) and estimated home ranges, core areas using kernel density estimates (KDE) and minimum convex polygons (MCPs). We found that subadults exhibit wider home range movements than adults and that subadults’ ranging areas (corresponding to the home range of adults) decreased from the first half to the second half of the summer. Breeding adults had the smallest home ranges, while one-year-old and two-year-old subadults had equally the largest ranging areas but which decreased significantly when subadults reached sexual maturity at three years old. Throughout the summer, the changing pattern of breeders was generally opposite to that of subadults. All subadult age groups had the largest ranging areas when breeders’ home ranges were the smallest during the incubation/nestling stage. This study highlights the difference between adults and subadults and contributes to subadult ecology.

Zusammenfassung

Jung, wild und frei—Junge Weißnackenkraniche ( Antigone vipio ) bewegen sich während des Sommers innerhalb eines größeren Areals als erwachsene, brütende Vögel

In der Tierökologie ist das Verständnis von Raumnutzung und deren Veränderung im Laufe der Zeit von entscheidender Bedeutung. Die subadulte Phase ist der Übergang vom Jungtier zum Erwachsenen, und ausgewachsene Tiere haben im Sommer andere biologische Erfordernisse als Jungtiere, was zu unterschiedlichen Mustern in der Raumnutzung führt. Von Juli bis August 2017 bis 2019 versahen wir in der östlichen Mongolei 66 Weißnackenkraniche (Antigone vipio), davon 22 adulte und 44 Jungtiere vom gleichen Jahr, mit GPS/GSM Peilsendern. Ziel war es, ihre jeweilige Raumnutzung zu erfassen und zu vergleichen, insbesondere die Heimatareale der Adulten und Subadulten, und die Muster über den Sommer hinweg zu untersuchen. Wir unterteilten die gesamte Sommerperiode in 6 Perioden (vor der Brutzeit, Brutzeit/Schlüpfen, vor der Mauser, Mauser/nach der Mauser, Abwanderung in andere Gebiete vor dem Herbstzug) und schätzten die Heimatgebiete und Kernbereiche anhand von Kernel-Dichte-Schätzungen (KDE) und minimaler konvexer Polygone (MCPs). Dabei stellten wir fest, dass die Jungtiere einen größeren Aktionsradius hatten als die adulten Tiere und dass die Aktionsbereiche der Subadulten (die den Heimatrevieren der Adulten entsprachen) von der ersten Hälfte des Sommers zur zweiten hin kleiner wurden. Brütende Tiere hatten den kleinsten Bewegungsradius, während ein und zwei Jahre alte Jungtiere ebenfalls die größten Aktionsgebiete hatten, die jedoch deutlich abnahmen, sobald sie im Alter von drei Jahren die Geschlechtsreife erreichten. Während des gesamten Sommers war der Wechsel im Verhalten der Brütenden im Allgemeinen dem der Jungtiere entgegengesetzt. Alle subadulten Altersgruppen hatten die größten Aktionsradien, während die der Brütenden während der Brutzeit/Nestlingsphase am kleinsten waren. Diese Untersuchung betont den Unterschied zwischen adulten und subadulten Tieren und leistet einen Beitrag zur Ökologie von Jungtieren.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to the protection of the White-naped Crane western population, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Batbayar N, Yi K, Zhang J, Natsagdorj T, Damba I, Cao L, Fox AD (2021) Combining tracking and remote sensing to identify critical year-round site, habitat use and migratory connectivity of a threatened waterbird species. Remote Sens 13:4049. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs13204049

Bennett AJ (1989) Movements and home ranges of Florida Sandhill Cranes. J Wildl Manage 53:830–836. https://doi.org/10.2307/3809221

BirdLife International (2021) Species factsheet: Antigone vipio. http://www.birdlife.org. Accessed 18 July 2021

Boulinier T, Danchin E (1997) The use of conspecific reproductive success for breeding patch selection in terrestrial migratory species. Evol Ecol 11:505–517. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10682-997-1507-0

Bradter U, Gombobaatar S, Uuganbayar C, Grazia TE, Exo K (2005) Reproductive performance and nest-site selection of White-naped Cranes Grus vipio in the Ulz river valley, north-eastern Mongolia. Bird Conserv Int 15:313–326. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959270905000663

Bradter U, Gombobaatar S, Uuganbayar C, Grazia TE, Exo K (2007) Time budgets and habitat use of White-naped Cranes Grus vipio in the Ulz river valley, north-eastern Mongolia during the breeding season. Bird Conserv Int 17:259–271. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959270907000767

Bridge ES, Thorup K, Bowlin MS, Chilson PB, Diehl RH, Fléron RW, Hartl P, Kays R, Kelly JF, Robinson WD, Wikelski M (2011) Technology on the move: recent and forthcoming innovations for tracking migratory birds. Bioscience 61:689–698. https://doi.org/10.1525/bio.2011.61.9.7

Burt WH (1943) Territoriality and home range concepts as applied to mammals. J Mamm 24:346–352. https://doi.org/10.2307/1374834

Buskirk WH (1980) Influence of meteorological patterns and trans-Gulf migration on the calendars of migrants to the Neotropics. In: Keast A, Morton ES (eds) Migrant birds in the Neotropics: ecology behavior, distribution, and conservation. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, DC, pp 485–493

Calenge C (2015) Home range estimation in R: the adehabitatHR Package. Office national de lasse et la faune sauvage Saint Benoist, Auffargis, France.

Chen J, John R, Sun G et al (2018) Prospects for the sustainability of social-ecological systems (SES) on the Mongolian plateau: five critical issues. Environ Res Lett 13:123004. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aaf27b

Cheng Y (2015) Home range and habitat selection of wintering White-naped Crane Grus vipio through GPS telemetry in Poyang Lake, China. Dissertation, Beijing Forestry University.

ESRI (2014) ArcGIS desktop: release 10.2.2. Environmental Systems Research Institute, Redlands, CA, USA.

Fujita G, Guan H, Ueta M, Goroshko O, Krever V, Ozaki K, Mita N, Higuchi H (2004) Comparing areas of suitable habitats along travelled and possible shortest routes in migration of White-naped Cranes Grus vipio in East Asia. Ibis 146:461–474. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1474-919X.2004.00286.x

Gavashelishvili A, McGrady M, Ghasabian M, Bildstein KL (2012) Movements and habitat use by immature cinereous vultures (Aegypius monachus) from the Caucasus. Bird Study 59:449–462. https://doi.org/10.1080/00063657.2012.728194

Gilbert M, Buuveibaarar B, Fine AE, Jambal L, Strindberg S (2016) Declining breeding populations of White-naped Cranes in Eastern Mongolia, a ten-year update. Bird Conserv Intern 26:490–504. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959270915000301

Gombobaatar S, Monks EM et al (2011) Mongolian red list of birds. Regional red list series, Vol. 7. Zoological Society of London, National University of Mongolia, Mongolian Ornithological Society. London and Ulaanbaatar.

Gorlov PI, Matsyura AV (2017) Pre-migratory congregations of red-crowned (Grus japonensis), White-naped (G. vipio) and Hooded (G. monacha) cranes in the Muraviovka Park for sustainable land use in 1992. Biosyst Divers 25:132–140. https://doi.org/10.15421/011720

Goroshko O, Tseveenmyadag N (2002) Status and conservation of cranes in Daurian steppes (Russia and Mongolia). China Crane News 6:5–7

Harris J, Su L, Higuchi H, Ueta M, Zhang Z, Zhang Y, Ni X (2000) Migratory stopover and wintering locations in eastern China used by White-naped Cranes Grus vipio and Hooded Cranes G. monacha as determined by satellite tracking. Forktail 16:93–99

Hayes MA (2015) Dispersal and population genetic structure in two flyways of Sandhill Cranes (Grus canadensis). Dissertation, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Hereford SG, Grazia TE, Phillips JN, Olsen GH (2010) Home range size and habitat use of Mississippi Sandhill Crane colts. In: Hartup BK (ed) Proceedings of North American Crane Workshop, September 23–27, 2008, Wisconsin Dells, Wisconsin. North American Crane Working Group, p 205

IBM (2017) IBM SPSS statistics for windows, version 25.0. IBM, Armonk, New York

Jia Y, Zhang Y, Lei J, Jiao S, Lei G, Yu X, Liu G (2019) Activity patterns of four cranes in Poyang Lake, China: indication of habitat naturalness. Wetlands 39:45–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13157-017-0911-7

Johns BW, Goossen JP, Kuyt E, Craig-Moore L (2005) Philopatry and dispersal in Whooping Cranes. In: Chavez-Ramirez F (ed) Proceedings of the Ninth North American Crane Workshop, January 17–20, 2003, Sacramento, California. North American Crane Working Group, pp. 117–126

Juggins S (2019) Rioja: analysis of quaternary science data [Internet]. https://cran.r-project.org/package=rioja

King DT, Fischer J, Strickland B, Walter WD, Cunningham FL, Wang G (2016) Winter and summer home ranges of American White Pelicans (Pelecanus erythrorhynchos) captured at loafing sites in the Southeastern United States. Waterbirds 39:287–294. https://doi.org/10.1675/063.039.0308

Lameris TK, Brown JS, Kleyheeg E, Jansen PA, van Langevelde F (2018) Nest defensibility decreases home-range size in central place foragers. Behav Ecol 29:1038–1045. https://doi.org/10.1093/beheco/ary077

Lang X, Purev-Ochir G, Terbish O, Khurelbaatar D, Erdenechimeg B, Gungaa A, Mi C, Guo Y (2020) Luan river upper reaches: the important stopover site of the White-naped Crane (Grus vipio) western population. Biodiv Sci 28:1213–1221. https://doi.org/10.17520/biods.2020100

Li F, Li P (1999) A comparative study on territories of White-naped Crane and Red-crowned Crane. Chin J Ecol 6:33–37

Li F, Li P, Yu X (1991) The primary study on territories of White-naped Cranes. Zool Res 12:29–34

Literák I, Raab R, Škrábal J, Vyhnal S, Dostál M, Matušík H, Makoň K, Maderič B, Spakovszky P (2022) Dispersal and philopatry in Central European Red Kites Milvus milvus. J Ornithol 163:469–479. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-021-01950-5

Liu F (2008) Habitat use of White-naped Crane (Grus vipio) in Zhalong wetland. Dissertation, Northeast Forestry University.

Liu W, Jin Y, Wu Y, Zhao C, He X, Wang B, Ran J (2020) Home range and habitat use of breeding Black-necked Cranes. Animals 10:1975. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10111975

López-López P, Perona AM, Egea-Casas O, Morant J, Urios V (2021) Tri-axial accelerometry shows differences in energy expenditure and parental effort throughout the breeding season in long-lived raptors. Curr Zool 68:57–67. https://doi.org/10.1093/cz/zoab010

Månsson J, Nilsson L, Hake M, Sveriges L (2013) Territory size and habitat selection of breeding common Cranes (Grus grus) in a boreal landscape. Ornis Fennica 90:65–72

Marques PAM, Sowter D, Jorge PE (2010) Gulls can change their migratory behavior during lifetime. Oikos 119:946–951. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0706.2009.18192.x

McCann KI, Benn GA (2006) Land use patterns within Wattled Crane (Bugeranus carunculatus) home ranges in an agricultural landscape in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Ostrich 77:186–194. https://doi.org/10.2989/00306520609485532

Mongolian Bird Conservation Center (2020) A report on surveys of the cranes along the Kherlen and Ulz rivers, eastern Mongolia – 2020. MBCC annual report – Eastern Mongolia

Mueller HC, Berger DD, Mueller NS (2003) Age and sex differences in the timing of spring migration of hawks and falcons. Wilson Bull 115:321–324. https://doi.org/10.1676/03-011

Murray DL, Sandercock BK (eds) (2020) Population ecology in practice. Wiley-Blackwell, New Jersey

Nesbitt SA, Williams KS (1990) Home range and habitat use of Florida Sandhill Cranes. J Wildl Manag 54:92–96. https://doi.org/10.2307/3808907

Newton I (2008) The migration ecology of birds. Academic Press, London

Ozaki K (2002) Ages of first breeding of Hooded and White-naped Cranes according to color banding research. In: Abstracts of international crane symposium, Beijing, China, 9 August 2002.

Patten MA, Pruett CL, Wolfe DH (2011) Home range size and movements of Greater Prairie-Chickens. In: Sandercock BK, Martin K, Segelbacher G (eds) Ecology, conservation, and management of grouse. Studies in Avian biology. University of California Press, Berkeley, pp 51–62

Peery MZ (2000) Factors affecting interspecies variation in home-range size of raptors. Auk 117(2):511–517. https://doi.org/10.1093/auk/117.2.511

Pickens BA, King SL, Vasseur PL, Zimorski SE, Selman W (2017) Seasonal movements and multiscale habitat selection of Whooping Crane (Grus americana) in natural and agricultural wetlands. Waterbirds 40:322–333. https://doi.org/10.1675/063.040.0404

R Core Team (2019) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/.

Reading RP, Azua J, Garrett T, Kenny D, Lee H, Paek WK, Reece N, Tsolmonjav P, Willis MJ, Wingard G (2020) Differential movement of adult and juvenile Cinereous vultures (Aegypius monachus) in Northeast Asia. J Asia Pac Biodivers 13:156–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.japb.2020.01.004

Rühmann J, Soler M, Pérez-Contreras T, Ibáñez-Álamo JD (2019) Territoriality and variation in home range size through the entire annual range of migratory great spotted cuckoos (Clamator glandarius). Sci Rep 9:6238. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-41943-2

Seaman DE, Millspaugh JJ, Kernohan BJ, Brundige GC, Raedeke KJ, Gitzen RA (1999) Effects of sample size on kernel home range estimates. J Wildl Manage 63:739–747. https://doi.org/10.2307/3802664

Simonoff JS (1996) Smoothing methods in statistics. Springer, New York

Sokolov VA, Lecomte N, Sokolov AA, Rahman ML, Dixon A (2014) Site fidelity and home range variation during the breeding season of peregrine falcons (Falco peregrinus) in Yamal, Russia. Polar Biol 37:1621–1631. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00300-014-1548-0

Son S, Kang J, Lee S, Kim I, Yoo J (2020) Breeding and wintering home ranges of the Black-faced Spoonbill Platalea minor. J Asia Pac Biodivers 13:7–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.japb.2020.01.001

Su L, Xu J, Zhou D (1991) Breeding habits of White-naped Cranes at Zhalong Nature Reserve. Proceedings of the 1987 International Crane Workshop. In: Harris JT (ed) Proceedings 1987 International Crane Workshop, May 1–10, 1987, Qiqihar, Heilongjiang Prov, China. International Crane Foundation, pp. 51–58

Subedi TR, Pérez García JM, Sah SAM, Gurung S, Baral HS, Poudyal LP, Lee H, Thomsett S, Virani MZ, Anadón JD (2020) Spatial and temporal movement of the Bearded vulture using GPS telemetry in the Himalayas of Nepal. Ibis 162:563–571. https://doi.org/10.1111/ibi.12799

Thompson LJ, Barber DR, Bechard MJ et al (2020) Variation in monthly sizes of home-ranges of Hooded vultures Necrosyrtes monachus in western, eastern and southern Africa. Ibis 162:1324–1338. https://doi.org/10.1111/ibi.12836

Ueta M, Higuchi H (2002) Difference in migration pattern between adult and immature birds using satellites. Auk 119:832–835. https://doi.org/10.1093/auk/119.3.832

Ueta M, Higuchi H, Ozaki K (2001) The timing of family break-up in White-naped Cranes. J Field Ornithol 19:141–148

Van Schmidt ND, Barzen JA, Engels MJ, Lacy AE (2014) Refining reintroduction of Whooping Cranes with habitat use and suitability analysis. J Wildl Manag 78:1404–1414. https://doi.org/10.1002/jwmg.789

van Velden JL, Altwegg R, Shaw K, Ryan PG (2017) Movement patterns and survival estimates of Blue Cranes in the Western Cape. Ostrich 88:33–43. https://doi.org/10.2989/00306525.2016.1224782

Veltheim I, Cook S, Palmer GC, Hill FAR, McCarthy MA (2019) Breeding home range movements of pre-fledged brolga chicks, Antigone rubicunda (Gruidae) in Victoria, Australia – implications for wind farm planning and conservation. Glob Ecol Conserv 20:e00703. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2019.e00703

Walter WD, Fischer JW, Baruch-Mordo S, VerCauteren KC (2011) What is the proper method to delineate home range of an animal using today’s advanced GPS telemetry systems: the initial step. In: Krejcar O (ed) Modern telemetry. IntechOpen, Rijeka, pp 249–268

Wang Z (2020) Molt timing and habitat distribution of White-naped Crane (Grus vipio) based on field observation and GPS-GSM tracking. Dissertation, Beijing Forestry University.

Wang W, Fraser JD, Chen J (2019) Distribution and long-term population trends of wintering waterbirds in Poyang Lake, China. Wetlands 39:125–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13157-017-0981-6

Wang Z, Dou Z, Se Y, Yang J, Na S, Yu F, Guo Y (2020) Autumn migration route and stopover sites of Black-necked Crane breeding in Yanchiwan Nature Reserve, China. Waterbirds 43:94–100. https://doi.org/10.1675/063.043.0110

Wen L (2017) Predicting White-naped Crane breeding habitat distribution and testing by GPS-GSM tracking data. Dissertation, Beijing Forestry University.

Wickham H (2016) Ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. Springer, New York

Winkler DW (2005) How do migration and dispersal interact? In: Greenberg R, Marra PP (eds) Birds of two worlds: the ecology and evolution of migration. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore and London, pp 401–413

Wolfson DW, Fieberg JR, Andersen DE (2020) Juvenile Sandhill Cranes exhibit wider ranging and more exploratory movements than adults during the breeding season. Ibis 162:556–562. https://doi.org/10.1111/ibi.12786

Worton BJ (1989) Kernel methods for estimating the utilization distribution in home-range studies. Ecology 70:164–168. https://doi.org/10.2307/1938423

Wu Q, Zou H, Ma J (2014) Nest site selection of white-naped crane (Grus vipio) at Zhalong National Nature Reserve, Heilongjiang, China. J For Res 25:947–952. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11676-014-0541-3

Wu H, Jin J, Nymbayar B, Li F, Ding C (2018) Wintering home range variation of White-naped Cranes Grus vipio and its correlation with water level and temperature in Poyang Lake. Chin J Zool 53:497–506. https://doi.org/10.13859/j.cjz.201804001

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the tireless efforts of the staff of Eastern Mongolian Protected Area Administration in crane capture and field observation. We thank Chunrong Mi for guidance on data analysis and review comments on this manuscript. Special thanks go to our friend herder family Dashdorj and Khurlee and their families and also to our great drivers Bundaa and Bayasaa.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant number 31770573]; Ministry of Science and Technology of the Republic of China [grant number G20190001114]; and the National Forestry and Grassland Administration of China.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. YG proposed ideas, supervised the research, and collected data. MG analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. BE helped with information searching. GPO helped with review and revision. BE, GPO, and AG helped with bird capture, satellite tracking and monitoring. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethical approval

This study was conducted under Mongolian laws on bird capture and handling. Capture and tracking work was performed under the licenses of the Ministry of Environment and Tourism of Mongolia (permission number: 06/2376, 06/2248).

Additional information

Communicated by N. Chernetsov.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, M., Erdenechimeg, B., Purev-Ochir, G. et al. Young, wild, and free—Subadult White-naped Crane (Antigone vipio) exhibit wider home range movements than breeding adults during the summering period. J Ornithol 164, 561–572 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-023-02053-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-023-02053-z