Abstract

Although the use of bird-borne data loggers has become widespread in avian field research, the effects of capture and transmitter attachment on behavior and demographic rates are not often measured. Tag- and capture-induced effects on individual behavior, survival and reproduction may limit extrapolation of transmitter data to wider populations. However, measuring individual responses to capture and tagging is a necessary step in developing research techniques that minimize negative effects. We measured the short-term behavioral effects of handling and GPS transmitter attachment on Brown Pelicans under both captive and field conditions, and followed tagged individuals through a full breeding season to assess whether capture and transmitter attachment increased rates of nest abandonment or breeding failure. We observed slight increases in preening among tagged individuals 0–2 h after capture relative to controls that had not been captured or tagged, with a corresponding reduction in time spent resting. One to three days post-capture, nesting behavior of tagged pelicans resembled that of neighbors that had not been captured or tagged. Eighty-eight percent of tagged breeders remained at the same nest location for more than 48 h after capture, attending nests and chicks for an average of 49 days, and 51% were assumed to successfully fledge young. Breeding success was driven primarily by variation in location; however, sex and handling time also influenced the probability of successful breeding in tagged pelicans, suggesting that individual characteristics and the capture process itself can confound the effects of capture and transmitter attachment. We conclude that pelicans fitted with GPS transmitters exhibit comparable behaviors to untagged individuals within a day of capture and that GPS tracking is a viable technique for studying behavior and demography in this species. We also identify measures to minimize post-capture nest abandonment rates in tracking studies, including minimizing handling time and covering nests during processing.

Zusammenfassung

Auswirkungen der Besenderung auf Verhalten und Fortpflanzung von Braunpelikanen ( Pelecanus occidentalis ) auf drei zeitlichen Skalen

Die Besenderung von Vögeln mit Datenloggern ist in der Feld-Vogelforschung inzwischen weit verbreitet, doch die Auswirkungen von Fang und Anbringen des Transmitters auf Verhalten und Demographie werden oftmals nicht erfasst. Solche durch Besenderung und Fang hervorgerufenen Auswirkungen auf individuelles Verhalten, Überleben und Fortpflanzung könnten die Extrapolation von Transmitterdaten auf die allgemeine Population limitieren. Individuelle Reaktionen auf Besenderung und Fang zu messen, ist ein notwendiger Schritt für die Entwicklung von Verfahren, mögliche negative Effekte zu minimieren. Wir haben die kurzfristigen Auswirkungen von Handhabung und Besenderung mit GPS-Transmittern auf das Verhalten von Braunpelikanen in Gefangenschaft und im Freiland untersucht. Mit Transmittern ausgestattete Individuen wurden eine Brutsaison lang verfolgt, um abzuschätzen, ob Fang und Besenderung zu häufigerem Verlassen des Nests oder verstärktem Brutverlust führen. Besenderte Tiere verbrachten im Vergleich zu Kontrolltieren, die nicht gefangen oder besendert wurden, in den ersten zwei Stunden nach dem Fang etwas mehr Zeit mit Gefiederpflege und dementsprechend weniger Zeit mit Ruhen. In den ersten drei Tagen nach dem Fang ähnelte das Brutverhalten der besenderten Pelikane dem von Nachbarn, die nicht gefangen oder besendert worden waren. 88% der besenderten Brutvögel blieben nach dem Fang für mehr als 48 Stunden am selben Neststandort und kümmerten sich um Nest und Küken für durchschnittlich 49 Tage; für 51% wird angenommen, dass sie Flügglinge produzierten. Der Bruterfolg wurde hauptsächlich durch Variation im Neststandort bestimmt; Geschlecht und Dauer der Handhabung beeinflussten ebenfalls die Wahrscheinlichkeit einer erfolgreichen Brut bei besenderten Pelikanen, was darauf hindeutet, dass individuelle Merkmale und der Fang selbst die Effekte von Fang und Besenderung maskieren können. Wir schlussfolgern, dass mit GPS-Transmittern ausgestattete Pelikane bereits einen Tag nach dem Fang ähnliches Verhalten wie unbesenderte Tiere zeigen und dass GPS-Ortung eine praktikable Methode ist, um Verhalten und Demographie bei dieser Art zu untersuchen. Wir zeigen außerdem Maßnahmen auf, die das Verlassen des Nests nach dem Fang in Ortungsstudien minimieren, einschließlich Minimieren der Handhabungsdauer und Abdecken des Nests während der Handhabung der Vögel.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Traditionally, investigation of seabird foraging and wintering habitat has relied on ship-based surveys (reviewed in Ballance 2008), color-marking (Calvo and Furness 1992) or band recoveries (Schreiber and Mock 1998). Individual tracking has become increasingly popular because of its flexibility, ease of access and broad applicability in the marine environment (Wakefield et al. 2009). Unlike survey or mark-recapture techniques, telemetry-based studies (Boyd et al. 2004) integrate year-round habitat use by known individuals, offer individual- and location-specific information on preferred foraging and wintering habitat, and identify marine areas of particular conservation importance that might not otherwise be recognized (Tancell et al. 2013). Telemetry studies also have potential drawbacks, however, including high costs, small sample sizes and the need to accurately represent individual and geographic variation when scaling up to population-level patterns (Hebblewhite and Haydon 2010).

One important, though often overlooked, component of interpreting telemetry data is assessing the extent to which carrying a payload (i.e., tracking device) impacts the survival, behavior and reproduction of individual birds (reviewed in Barron et al. 2010). Tag effects have the potential to restrict inferences drawn from tracking data if the activities of tagged birds differ from the behavior of untagged individuals (Igual et al. 2005). As the effects of both handling and tagging may vary among and within species (Barron et al. 2010; Vandenabeele et al. 2012), it is important to understand whether and how individual tracking data might be impacted by tag-induced behavioral changes for specific species under study. Moreover, tagging also has the potential to reduce breeding success or increase mortality rates, which are of particular concern in imperiled species (Carey 2009). For example, seabirds are among the most threatened avian taxa globally (Croxall et al. 2012), and their limited reproductive output—typically only 1–2 young per year—means that the survival and condition of breeding adults play a crucial role in population dynamics (Fredricksen et al. 2008). Despite these concerns, most tracking studies do not directly assess the impacts of the tags on the behavior or reproduction of seabirds (Vandenabeele et al. 2011).

Brown Pelicans (Pelecanus occidentalis) have long been a focal species for coastal conservation and oil spill restoration (Levy and Gopalakrishnan 2010). Their sensitivity to contaminants exposure (Blus et al. 1979) and high mortality and morbidity during oil spills (Anderson et al. 1996; Haney et al. 2014; Jernelöv and Lindén 1981), combined with their large population sizes and visibility and tendency to nest in dense colonies, make them a strong indicator species for studying ecological functioning of nearshore marine systems. In comparison to other seabirds, Brown Pelicans are considered unusually sensitive to human disturbance during breeding (Anderson 1988); however, recent research (e.g., Eggert et al. 2010; Sachs and Jodice 2009) has demonstrated that nestling pelicans can be studied at breeding colonies without inducing nest abandonment or negatively impacting breeding success. This raises the possibility of collecting individual data on pelican breeding biology and movement ecology as a baseline for studying the impacts of future perturbations. To date, most GPS tracking of adult Brown Pelicans has been conducted on non-breeding individuals away from breeding colonies (Croll et al. 1986; Evers et al. 2011; King et al. 2013). The only previous study in which breeding Brown Pelicans were captured and tracked at colony sites (Walter et al. 2014) recorded large-scale nest abandonment by GPS-tagged pelicans, indicating that the capture and tagging process may alter individual behavior. However, none of these studies tested for the presence of device effects, compared tracked pelicans to untagged controls or measured variation in individual responses to capture or device attachment.

To better understand how capture and tagging affects Brown Pelicans, we compared the behavior and breeding activity of adult pelicans that had been captured, handled and fitted with GPS transmitters to untagged individuals. Behavior data were collected both in a captive setting (rehabilitation center, 0–2 h post capture) and on breeding colonies (1–3 days post capture), while nesting duration and apparent nesting success were measured for breeding pelicans captured and fitted with GPS transmitters on colonies. Our study provides an opportunity to assess the impacts of a common research practice (individual tagging) on a species of conservation concern, evaluates factors contributing to variation in tag effects between individuals and provides a template for designing field- and captive-based studies of tag impacts on free-ranging and rehabilitated seabirds.

Methods

Transmitter type and attachment

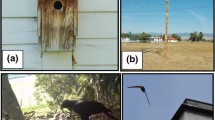

We tracked all individuals in this study using 65-g platform terminal GPS transmitters (GPS-PTTs: GeoTrak Inc.). Transmitters were constructed with sloped fronts to mimic pelican body contours and minimize resistance during movement (Bannasch et al. 1994). Transmitter weights as a percentage of body mass ranged from 1.5 to 1.7% (μ = 1.6%) in the captive trial and from 1.5 to 2.9% (μ = 1.9%) in the field trial, below the 3% threshold generally considered acceptable for seabirds (Phillips et al. 2003). We attached transmitters dorsally between the wings using a backpack-style Teflon ribbon harness (Fig. 1). The harness consisted of two loops of ribbon circling the body in front of and behind the wings and attached to one another with a short perpendicular connecting ribbon along the sternum, as described in Dunstan (1972). We custom-fitted harnesses at the time of attachment and secured the harness components using cyanoacrylate-covered square knots.

Behavioral effects: captive

On 11 June 2015, we fitted five adult California Brown Pelicans (P. californicus) with GPS transmitters at the Los Angeles Oiled Bird Care and Education Center rehabilitation facility in San Pedro, California. These individuals had been oiled during the Refugio Oil Spill on 19 May 2015, had undergone cleaning and rehabilitation and were being prepared for release at the time of transmitter attachment.

All GPS-tagged pelicans were released into a 6 × 13 × 5-m outdoor net enclosure containing a large pool and several perches 4 m in elevation, and filmed for 142 min pre- and 167 min post-transmitter attachment, for a total of ~5 h (309 min) per individual and 25 total observation hours. Staff rehabilitators used measured culmen length to determine the sex of individual birds. Four additional adult pelicans that did not receive transmitters, which had also been cleaned and rehabilitated following oiling in the Refugio spill, were housed in the same enclosure and filmed during the same period of time served as behavioral controls. Since handling and transmitter attachment were conducted in the early afternoon, the pre-tagging period coincided with mid-day, while the post-tagging period took place in late afternoon and evening. Sex of control pelicans was not determined.

We used EthoLog 2.2 software (Ottoni 2000) to record behaviors of all pelicans during the pre- and post-attachment phases. To minimize observer bias, all coding was done by the same observer (JSL). Behaviors included six mutually exclusive state events: resting (standing or crouching with neck folded and head down), loafing (standing or crouching with head up), perching (standing or crouching in a location accessible only by flight), preening (using beak or feet to rearrange feathers), swimming (floating or paddling on water) and flying. In addition, we recorded nine instant events that could occur during behavioral states: walking, flapping (extension and rapid movement of wings while standing), stretching (brief extension of neck, leg or wing), scratching, eating, shaking (brief, rapid movement while stationary), bathing (splashing in water), diving (completely underwater) and interacting (behaviors directed at or responding to other individuals). For state events, we recorded duration to the nearest second; for instant events, we recorded the total number of occurrences. We standardized the frequencies of observed behaviors by dividing the duration (state events) or number (instant events) by total observation time in seconds. To control for underlying differences in behavior during the two observation sessions, we calculated individual differences in each behavioral state before and after tagging and then calculated the mean and standard error of all pairwise comparisons of behavioral change between tagged and untagged pelicans.

Behavioral effects: field

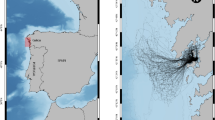

We captured and attached GPS transmitters to breeding adult Eastern Brown Pelicans (P. carolinensis) at nest sites in six colonies: two colonies per region in the eastern, central and western regions of the northern Gulf of Mexico (Fig. 2). Sixty pelicans were captured between 26 April and 3 July 2013, and 25 between 26 April and 29 May 2014, with a maximum of one adult captured per nest. All adults were captured on nests using leg nooses during the late incubation and early chick-rearing stages. At the time of capture, we recorded nest stage as late incubation (eggs), early chick-rearing (small chicks, no feathers or down, <1 week) or medium chicks (downy, 1–2 weeks). During the adult’s absence, a plastic laundry basket was placed over the nest to protect nest contents from weather and predation. Median handling time was 17.5 min from capture to release and included blood sampling, transmitter attachment and standard physiological measurements. We later used DNA from blood samples to determine the sex of all captured adults (Itoh et al. 2001). Blood sample volumes represented <0.1% of body weight, well below the recommended sampling volume and below levels at which blood sampling has been found to affect adult survival (Brown and Brown 2009; Sheldon et al. 2008).

During the 1–3 days following capture, we conducted 3-h behavioral observations of all GPS-tracked adults present at nests during return visits to the colony (N = 35 individuals; 105 observation hours). The remaining individuals (n = 50) were not available for observation during return visits within 3 days of capture, either because of nest failure (see “Results”) or because their mates were attending the nest at the time. We conducted all observations from outside the breeding area (~100 m from focal nests) using binoculars with 10× magnification. We approached observation points from the colony edge to limit disturbance at the focal nest and surrounding nests. If we observed a behavioral response (e.g., shifts from head-down resting to head-up alert posture) from any individuals in the focal group during approach, we increased the observation distance and did not begin observations until all individuals had returned to their original behavioral states.

Before beginning the observation, we paired each observed nest with a nearby (≤2 m distance) nest at the same phenological stage as each focal nest (i.e., incubation, small chick-rearing or large chick-rearing) to act as a control for comparison of behaviors. Because we were observing multiple birds during a single observation period, we used a snapshot approach to recording behavior. Every 5 min during the observation, we observed and recorded the instantaneous behavioral state of the tagged and control adults, classifying behaviors as resting (standing or crouching with neck folded and head down), alert (standing or crouching with head up), preening (using beak or feet to rearrange feathers) or agitated (alert and exhibiting signs of stress including walking, interacting or flapping). For each individual observed, we calculated the percent of observations assigned to each behavioral state. We then separated the data by behavior and used paired t tests to compare the frequency of each behavior between GPS-tagged and untagged individuals.

Nesting success

We calculated post-capture nest attendance and apparent nesting success using GPS location data from tagged individuals. Of the 85 transmitters deployed, we excluded transmitters that did not continue reporting for at least 60 days after inferred hatching dates (N = 11) resulting in a sample of 74 individuals (colony-specific sample sizes listed in Fig. 2). The excluded transmitters experienced abnormal transmission schedules and rapid loss of battery power despite GPS locations indicating normal movement, which suggests device failure rather than mortality.

We considered nests to be active for as long as adults continued to visit the nesting colony at least once a day. We determined approximate hatching dates from nest stage at date of capture, and, for the purposes of this study, considered breeding successful if adult attendance continued for at least 60 days after hatch. After this point, nestlings become flight-capable and may leave the breeding colony (Shields 2014), and although adults may continue to visit the colony, they generally cease to feed nestlings after 60 days of age (Montgomery and Martínez 1984). Our own observations indicate that mortality of nestlings older than 8 weeks is extremely rare, making 60 days an appropriate cutoff for determining that a nest has successfully fledged young (Lamb 2016). For pelicans that re-nested following capture, we interpreted the start of attendance at the new site as the beginning of incubation and used a 90-day cutoff for successful breeding, incorporating 30 days of incubation (Shields 2014) in addition to the 60-day fledging period. Thus, we were able to infer whether tagged adults successfully fledged at least one nestling (i.e., apparent nest success), but not how many nestlings were produced (i.e., fledging success or nest productivity). We compared inferred nest success rates to measured nest success of untagged individuals in the same study area in 2014–2015. To measure apparent nest success directly, we marked individual nests prior to hatching and recorded nestling presence/absence every 3–5 days from hatch through 60 days post-hatch. Nestlings were color-banded at 3–4 weeks of age to ensure that they could be followed after leaving the nest site. For full details of nest productivity monitoring methods and results, see Lamb (2016) and Lamb et al. (in review).

To assess factors influencing individual post-capture nest survival and breeding success, we used a generalized linear modeling framework to model the probability that parents would attend the nest for at least 60 days after hatch, which we interpreted as apparent nest success (binomial function, Bernoulli with logit link), as a function of individual, phenological, geographic and capture-related covariates. Individuals with malfunctioning transmitters (N = 11) and individuals that re-nested after capture (N = 6) were excluded from this portion of the analysis, leaving a sample of 68 individuals. Covariates included in our models included handling time, nest stage, sex, body condition index (BCI: residual of the linear relationship between mass and culmen length), payload (transmitter mass as percentage of body weight, standardized by sex), Julian date of capture, capture year and capture location (i.e., breeding colony) as predictor variables. Since handling time decreased during the breeding season, we detrended handling time prior to analysis by subtracting the linear relationship of handling time to capture date. We used a Hosmer-Lemeshow Goodness of Fit test to assess the fit of the global model and compared models using Akaike’s information criterion (AIC) values. Models were preferred if they resulted in a decrease in AIC of ≤2 relative to the best-fitting model (Burnham and Anderson 2004). We estimated means-parameterized model-averaged coefficients over the suite of preferred models, weighted by AIC weights.

Results

Behavioral effects

Before treatment, captive pelicans spent the majority of their time loafing (18–47%), preening (11–32%) or resting (20–49%). Swimming, perching and flying each occupied <10% of individual time budgets. In the first 1–2 h after receiving transmitters, GPS-tagged individuals spent an increased percentage of time preening (mean = +16.4%, F (1,7) = 6.41, p = 0.038) and decreased time resting (mean = −29.1%, p = 0.047, F (1,7) = 5.62) relative to individuals that had not been tagged or handled (Fig. 3). Changes in time spent swimming, flying, loafing and perching did not differ from zero (Fig. 3; Table S1). We did not find significant differences in frequency (events hour−1) after tagging for any of the instant events we quantified (Fig. 3b; Table S1). In free-ranging pelicans 1–3 days post-capture, we did not observe differences between tagged individuals and untagged neighbors in the proportion of observation time spent in preening (t 31 = −0.59, p = 0.56), resting (t 31 = −0.88, p = 0.38), alert/loafing (t 31 = 1.60, p = 0.12) or agitated (t 31 = −1.42, p = 0.17) behavioral states (Fig. 4).

Percentage time spent of Brown Pelicans in different behavioral states for tagged individuals (dark grey) and untagged neighbors (light grey) 1–3 days after capture in field trials in the northern Gulf of Mexico. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. All differences between tagged and untagged individuals were non-significant (p > 0.05)

Nesting success

Overall, GPS-tagged pelicans (N = 74) continued attending nests for an average of 50 (SD ± 34; range 0–113) days after capture, with a 51% apparent success rate for breeding (N = 38 successful nests). Apparent success rates of tagged breeders was slightly lower than, but did not differ significantly from, success rates of untagged adults measured in the same colonies in 2014–15 (62%; N = 482; \(\chi^{2}_{1}\) = 3.46; p = 0.06). The majority (88%; N = 65) continued breeding at their original nest sites following capture. The remaining adults either abandoned the breeding colony within 1 day of capture and did not re-nest that season (N = 3), re-nested at a different nest site in the same breeding colony (N = 3) or re-nested at different breeding colonies between 30 and 65 km from the original nesting colony (N = 3) (Table 1). Successful breeders attended colony sites for an average of 83 days after hatch (SD ± 13 days) while unsuccessful breeders attended on average 18 days (SD ±14.7 days). We observed successful breeding in pelicans that re-nested elsewhere as well as pelicans that remained at their original nest sites (Table 1). Breeding success was similar in the eastern (76%) and central (67%) regions and lower in the western (15%) region (Fig. 5). In the eastern region, breeding success of tagged pelicans in 2013–14 was similar to that of untagged pelicans at the same study colonies in 2015 (72%: \(\chi^{2}_{1}\) = 0.23; p = 0.63). In the western region, breeding success was lower in tagged pelicans in 2013–14 than in untagged pelicans in 2014 (45%; \(\chi^{2}_{1}\) = 9.91; p = 0.002). We did not measure breeding success of untagged pelicans at the central colonies in any of the 3 study years.

The global model predicting breeding success of tagged birds was a good fit for the observed data, indicating that the full suite of parameters effectively explained variation in breeding success (\(\chi^{2}_{8}\) = 1.85, p = 0.99). The four best-performing models for breeding success included capture location (Table 2), an index of underlying regional variability. The model-averaged coefficient estimates (±SE) for location, with the eastern region set as the reference location, were −0.43 ± 0.66 for the central region and −2.83 ± 0.75 for the western region. Two of the top models also included handling time (−0.64 ± 0.54), and two included sex (0.67 ± 0.56). Phenological variables (capture date and nest stage), year of capture, physical condition (BCI) and percent body mass of transmitters were not included in the best-performing models for breeding success. Handling time at capture was significantly longer in unsuccessful than successful breeders (t 55 = 1.7, one-tailed p = 0.047), with a significant decrease in breeding success among birds that were handled for more than 20 min (Fig. 5: Fisher’s exact test, one-tailed p = 0.045). Sex did not differ significantly between successful and unsuccessful breeders (Fig. 5: Fisher’s exact test, one-tailed p = 0.33); however, females were more likely than males to abandon or re-nest within 1 day of capture (Fisher’s exact test, one-tailed p = 0.045).

Discussion

We observed short-term behavioral effects of handling and transmitter attachment in a captive setting 1–2 h post-release, but not in a field setting 1–3 days post-release. Captive and free-ranging groups were observed under different conditions and had different histories, and, because of these differences, the behavioral patterns we observed in captive birds may differ from those of free-ranging individuals. However, both captive and free-ranging pelicans were observed relative to control individuals under the same conditions that were not captured or GPS-tagged. The fact that we observed behavioral changes immediately after transmitter attachment but did not observe similar changes within several days of capture suggests that behaviors indicative of stress or discomfort in our study, whether due to the attached device, the harness, the capture process or any combination of the above, diminished rapidly. Although we did not separate handling from device effects (i.e., include procedural controls), the process of fitting an individual with a transmitter inevitably involved both handling and device effects. A meta-analysis by Barron et al. (2010) found that behavioral effects of transmitter attachment are generally indistinguishable between studies with and without procedural controls, indicating that most effects can be attributed to the device alone.

Immediately after transmitter attachment, we observed differences in tagged captive birds in time spent preening and resting relative to controls. Since both handling and harness attachment may disrupt plumage and reduce waterproofing, increased preening behavior suggests an attempt to restore feather structure and represents a potential short-term increase in energy expenditure following handling and transmitter attachment. Other behaviors (swimming, perching, flying, loafing and instantaneous events) did not increase or decrease following transmitter attachment. As swimming and flight are particularly critical to foraging, migrating, provisioning chicks and escaping predators, these behaviors are often tested for adverse effects of transmitter attachment (Pennycuick et al. 2012; Matyjasiak et al. 2016). Our results suggest that individuals fitted with external transmitters continued to engage in swimming and flight at similar rates to control individuals immediately post-capture. However, our observations are limited to captive birds in a small enclosure, and we did not measure foraging movements or flight and swimming behavior in the field. Further, we did not assess the speed or efficiency of either swimming or flight, which can be altered by the presence of an external transmitter (Barron et al. 2010; Vandenabeele et al. 2011).

All supported models for breeding success included capture location as a predictor variable, which may result from underlying regional differences in breeding success rather than from capture and tracking. Currently, there are limited data on factors affecting productivity in Brown Pelicans throughout their range. However, Walter et al. (2014) also reported regional differences within the state of Louisiana in failure rates of nests of Brown Pelicans following capture and GPS-tagging, suggesting that nesting success may vary spatially depending on underlying conditions such as prey distribution, habitat availability and environmental conditions. In 2015, we recorded similar apparent brood success rates of untagged Brown Pelicans in the eastern region to those recorded for tagged pelicans in 2013–2014. However, at the two Texas colonies included in this study, we measured apparent nest success in 2014 of 45% among untagged breeders, significantly greater than the 15% success rate observed among tagged breeders at the same locations. Thus, while overall breeding success in the western region appeared to be lower among untagged as well as tagged individuals, individuals in the western region may also have experienced greater negative effects of tagging on breeding success. It is important to note that measured rates of nest success for Brown Pelicans in previous studies have ranged widely between years and locations (Shields 2014), and direct comparisons are limited by likely inter-annual variation and the small sample size of tagged pelicans relative to untagged individuals. Further assessment of the environmental factors underlying regional variation in nest productivity could help to elucidate the conditions under which tagging may depress nesting success.

Handling time appeared in two of the top models for breeding success. Longer handling periods resulted in a decrease in breeding success, with sharply reduced breeding success among birds that were handled for more than 20 min. Adults handled for longer periods of time spent more time away from the nest during handling, which resulted in longer exposure of eggs to ambient temperature and may have affected egg viability. Longer periods of high stress resulting from handling may also have affected adult condition and likelihood of returning to the nest site. Effects of increased handling time on behavior have also been observed by Jodice et al. (2003) for Black-legged Kittiwakes (Rissa tridactyla). Handling time decreased during the course of our study, suggesting that researcher experience is an important factor in minimizing the effects of capture and tagging.

Sex also appeared as a predictor in two of the four top models. Although we did not observe a significant difference in breeding success between tagged male and female pelicans, our results indicate that females may be more likely than males to abandon immediately after being captured and fitted with GPS transmitters. As pelicans are sexually dimorphic, the percentage of body weight represented by a transmitter is higher for females (μ = 2.2 ± 0.2%) than for males (μ = 1.7 ± 0.1%). However, sex alone remained the strongest individual-level predictor of breeding success and transmitter mass, and neither body condition nor transmitter payload improved model fit. Transmitter weight represented <3% of body mass for all individuals included in this study, which is generally considered an acceptable payload for seabirds (Phillips et al. 2003, although see Vandenabeele et al. 2012 for discussion of the limitations of this rule). There is limited evidence that females of some seabird species may take longer than males to recover from disturbance (Weimerskirch et al. 2002) and may be more sensitive to environmental conditions (Jodice et al. 2003). Female seabirds can also exhibit higher baseline corticosterone levels than males following the physiologically intensive egg-laying process (Goutte et al. 2010; Lormée et al. 2003), which may exacerbate the effects of stressors such as capture and handling.

We did not observe the high rates of nest failure previously reported in GPS-tagged Brown Pelicans in the northern Gulf of Mexico following transmitter attachment (Walter et al. 2014). Our study included pelicans from a much broader geographic range, but among breeders from the central region of our study, comparable to the Louisiana study area in Walter et al. 2014, we also observed a lower rate of relocation and nest failure (48% in our study vs. 94% in Walter et al. 2014), a lower rate of abandonment within 48 h of tagging (19 vs. 44%) and a longer duration of nesting among breeders that remained on their original nest sites but eventually failed (40 ± 9 days in our study, vs. 7 ± 10 days in Walter et al. 2014). Both studies used the same capture method, transmitter weight and profile, attachment location and harness shape. However, average handling times were significantly shorter in our study (18.8 ± 6.5 min) compared to the previous study (ca. 45 min: S. Walter, personal communication.). This was likely due to differences in harness attachment methods. While the previous study used metal clamps and sutures to fasten harnesses, our study used knots covered in cyanoacrylate, which could be secured more rapidly. Additionally, following observations by the authors of the previous study that neighboring pelicans would often destroy unattended nests, we used a plastic mesh basket to protect nest contents while captured adults were absent from the nest. These differences may have contributed to lower rates of abandonment and egg loss in our study. Future tracking studies of nesting Brown Pelicans might include such precautions to ensure that nest contents are protected during the tagging process and to improve the likelihood of successful breeding by tracked adults.

Our study suggests that capture and GPS-tagging in Brown Pelicans results in short-term behavioral effects, but that these effects are minimal and do not persist into the days following transmitter attachment. According to our data, behavioral changes resulting from the transmitter attachment process could be accounted for by excluding locations obtained during the first 24 h after transmitter attachment in order to avoid biased inference in GPS data analysis. Our study also indicates that tagged individuals can continue breeding and successfully raise young following capture and that efforts to minimize handling time and protect nest contents during capture may contribute to improved nesting success. However, female breeders and individuals in relatively poor breeding locations may be more likely to abandon after capture and transmitter attachment. Since our study included only the breeding season following capture, we did not assess long-term effects of transmitter attachment on adult overwinter or inter-annual survival or on lifetime fitness. While reproductive and survival values are key to understanding the demographic effects of perturbations such as researcher disturbance, baseline data on these parameters are lacking in this and many seabird species. Future studies are needed on long-term impacts of carrying a GPS transmitter on site fidelity, survival and reproductive success in the years following transmitter attachment in pelicans and other seabirds.

References

Anderson D (1988) Dose–response relationship between human disturbance and Brown Pelican breeding success. Wildlife Soc Bull 16(339–345):432

Anderson DW, Gress F, Fry DM (1996) Survival and dispersal of oiled brown pelicans after rehabilitation and release. Mar Pollut Bull 32:711–718

Ballance LT (2008) Understanding seabirds at sea: why and how? Mar Ornithol 35:127–135

Bannasch R, Wilson RP, Culik B (1994) Hydrodynamic aspects of design and attachment of a back-mounted device in penguins. J Exp Biol 194:83–96

Barron DG, Braun JD, Weatherhead PJ (2010) Meta-analysis of transmitter effects on avian behaviour and ecology. Meth Ecol Evol 1:180–187

Blus L, Cromartie E, McNease L, Joanen T (1979) Brown pelican: population status, reproductive success, and organochlorine residues in Louisiana, 1971–1976. B Environ Contam Tox 22:128–134

Boyd IL, Kato A, Roper-Coudert Y (2004) Bio-logging science: sensing beyond the boundaries. Memoirs Nat Inst Polar Res 58:1–14

Brown MB, Brown CR (2009) Blood sampling reduces annual survival in cliff swallows (Petrochelidon pyrrhonota). Auk 126:853–861

Burnham KP, Anderson DR (2004) Multimodel inference: understanding AIC and BIC in model selection. Sociol Meth Res 33:261–304

Calvo B, Furness RW (1992) A review of the use and the effects of marks and devices on birds. Ring Migrat 13:129–151

Carey MJ (2009) The effects of investigator disturbance on procellariiform seabirds: a review. N Z J Zool 36:367–377

Croll DA, Balance LT, Würsig BG, Tyler WB (1986) Movements and daily activity patterns of a Brown Pelican in central California. Condor 88:258–260

Croxall JP, Butchart SH, Lascelles B, Stattersfield AJ, Sullivan B, Symes A, Taylor P (2012) Seabird conservation status, threats and priority actions: a global assessment. Bird Cons Int 22:1–34

Dunstan TC (1972) A harness for radio-tagging raptorial birds. Inland Bird Banding News 44:4–8

Eggert LMF, Jodice PGR, O’Reilly KM (2010) Stress response of Brown Pelican nestlings to ectoparasite infestation. Gen Comp Endocr 166:33–38

Evers D, Jodice PGR, Frederick PC, Eggert L, Meyer KD, Yates M, Flegel CS, Meattey JD, Duron M, Goyette J, McKay J (2011) Final pre-assessment data report: estimating oiling and mortality of breeding colonial waterbirds from the deepwater horizon oil spill, NRDA Deepwater Horizon (MC 252) Oil Spill (Bird Study#4). Page 42. Deepwater Horizon Trustee Council, Fairhope

Fredricksen M, Daunt F, Harris MP, Wanless S (2008) The demographic impact of extreme events: stochastic weather drives survival and population dynamics in a long-lived seabird. J Anim Ecol 77:1020–1029

Goutte A, Angelier F, Chastel CC, Trouvé C, Moe B, Bech C, Gabrielsen GW, Chastel O (2010) Stress and the timing of breeding: glucocorticoid-luteinizing hormones relationships in an arctic seabird. Gen Comp Endocr 169:108–116

Haney JC, Geiger HJ, Short JW (2014) Bird mortality from the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. II. Carcass sampling and exposure probability in the coastal Gulf of Mexico. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 513:239–252

Hebblewhite M, Haydon DT (2010) Distinguishing technology from biology: a critical review of the use of GPS telemetry data in ecology. Philos Trans R Soc Lond Biol Sci 365:2303–2312

Igual JM, Ferrero MG, Taveccia G, Gonzalez-Solis J, Martinez-Abrain A, Hobson KA, Ruiz X, Oro D (2005) Short-term effects of data loggers on cory’s shearwater (Calonectris diomedia). Mar Biol 146:619–624

Itoh Y, Suzuki M, Ogawa A, Munechika I, Murata K, Mizuno S (2001) Identification of the sex of a wide range of carinatae birds by PCR using primer sets selected from chicken EE0.6 and its related sequences. J Hered 92:315–321

Jernelöv A, Lindén O (1981) Ixtoc I: a case study of the world’s largest oil spill. Ambio 10:299–306

Jodice PGR, Roby DD, Suryan R, Irons DB, Kaufmann AM, Turco KR, Visser GH (2003) Variation in energy expenditure among black-legged kittiwakes: effects of activity-specific metabolic rates and activity budgets. Physiol Biochem Zool 76:375–388

King DT, Goatcher BL, Fischer JW, Stanton J, Lacour JM, Lemmons SC, Wang G (2013) Home ranges and habitat use of Brown Pelicans (Pelecanus occidentalis) in the northern Gulf of 486 Mexico. Waterbirds 36:494–500

Lamb JS (2016) Ecological drivers of Brown Pelican movement patterns and reproductive success in the Gulf of Mexico. Dissertation, Clemson University, Clemson

Lamb JS, O’Reilly KM, Jodice PGR (2016) Physical condition and stress levels during early development reflect feeding rates and predict pre- and post-fledging survival in a nearshore seabird. Cons Physiol (In review)

Levy JK, Gopalakrishnan C (2010) Promoting ecological sustainability and community resilience in the US Gulf coast after the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill. J Nat Resour Policy Res 2:297–315

Lormée H, Jouventin P, Trouve C, Chastel O (2003) Sex-specific patterns in baseline corticosterone and body condition changes in breeding red-footed boobies Sula sula. Ibis 145:212–219

Montgomery GG, Martínez ML (1984) Timing of Brown Pelican nesting on Taboga Island in relation to upwelling in the Bay of Panama. Colon Waterbirds 7:10–21

Ottoni EB (2000) EthoLog2.2: a tool for the transcription and timing of behavior observation sessions. Behav Res Meth Ins C 32:446–449

Pennycuick CJ, Fast PL, Ballerstädt N, Rattenborg N (2012) The effect of an external transmitter on the drag coefficient of a bird’s body, and hence on migration range, and energy reserves after migration. J Ornithol 153:633–644

Phillips RA, Xavier JC, Croxall JP (2003) Effects of satellite transmitters on albatrosses and petrels. Auk 120:1082–1090

Sachs EB, Jodice PGR (2009) Behavior of parent and nestling Brown Pelicans during early brood-rearing. Waterbirds 32:276–281

Schreiber RW, Mock PJ (1988) Eastern Brown Pelicans: what does 60 years of banding tell us? J Field Ornithol 59:171–182

Sheldon LD, Chin EH, Gill SA, Schmaltz G, Newman AEM, Soma KK (2008) Effects of blood collection on wild birds: an update. J Avian Biol 39:369–378

Shields M (2014) Brown Pelican (Pelecanus occidentalis), The Birds of North America Online (A. Poole, Ed.). Ithaca, NY: Cornell Lab of Ornithology. http://bna.birds.cornell.edu/bna/species/609. Accessed 4 June 2016

Tancell C, Phillips RA, Xavier JC, Tarling GA, Sutherland WJ (2013) Comparison of methods for determining key marine areas from tracking data. Mar Biol 160:15–26

Vandenabeele SP, Wilson RP, Grogan A (2011) Tags on seabirds: how seriously are instrument- induced behaviors considered? Anim Welf 20:559–571

Vandenabeele SP, Shepard EL, Grogan A, Wilson RP (2012) When three per cent may not be three percent; device-equipped seabirds experience variable flight constraints. Mar Biol 159:1–14

Wakefield ED, Phillips RA, Matthiopoulos J (2009) Quantifying the habitat use and preferences of pelagic seabirds using individual movement data: a review. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 391:165–182

Walter ST, Leberg PL, Dindo JJ, Karubian JK (2014) Factors influencing Brown Pelican (Pelecanus occidentalis) foraging movement patterns during the breeding season. Can J Zool 92:885–891

Weimerskirch H, Shaffer SA, Mabille G, Martin J, Boutard O, Rouanet JL (2002) Heart rate and energy expenditure of incubating wandering albatrosses: basal levels, natural variation, and the effects of human disturbance. J Exp Biol 205:475–483

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the US Department of the Interior, Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Environmental Studies Program, Washington, DC, through Inter-Agency Agreement Number M12PG00014 with the US Geological Survey. Field research was conducted with permission from the Clemson University Animal Care and Use Committee (2013-026). Permitting for field data collection was provided by the US Geological Survey Bird Banding Laboratory (22408), Texas Parks and Wildlife (SPR-0113-005), Audubon Texas, The Texas Nature Conservancy, Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries (LNHP-13-058 and LNHP-14-045) and the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (LSSC-13-00005). E. Ford and S. Desaivre helped conduct behavioral observations and capture pelicans in the Gulf of Mexico. A. MacMillan and L. Besaury assisted with genetic sexing of pelicans. Additional support was provided by T. King, S. Walter, T. and P. Wilkinson, M. Dumesnil and B. Hardegree. California GPS tracking was funded by the Oiled Wildlife Care Network. Assistance was provided by M. Ziccardi, K. Mills-Parker, R. McMorran, R. Golightly, L. Henkel and the International Bird Rescue staff at the Los Angeles Oiled Bird Care and Education facilities. Videos were recorded by J. Cox of the One Health Institute, University of California, Davis. We thank R. Ronconi, R. Baldwin, Y. Kanno and R. Suryan for comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript. The South Carolina Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit is jointly supported by the US Geological Survey, South Carolina DNR and Clemson University. Any use of trade, firm or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the US Government. All research was conducted in concordance with current laws of the US.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by C. Barbraud.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Lamb, J.S., Satgé, Y.G., Fiorello, C.V. et al. Behavioral and reproductive effects of bird-borne data logger attachment on Brown Pelicans (Pelecanus occidentalis) on three temporal scales. J Ornithol 158, 617–627 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-016-1418-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-016-1418-3