Abstract

A remarkable number of new vertebrate species have been discovered in Tanzania in the last 30 years. These discoveries have mainly been centred in the montane highlands, particularly the Eastern Arc Mountains. More recently, research in the often difficult to access interior of Tanzania has begun to reveal a unique avian community with associated endemic taxa. One such endemic taxon is the collaris race of the White-headed Black Chat Myrmecocichla arnotti. First described by Reichenow in 1882, collaris was found to be morphologically distinct from the nominate form, in that females possess a complete white collar. However, due to a lack of knowledge about the development of adult plumage, the distributional range, and the lack of diagnostic features among males of the different White-headed Black Chat races, collaris specimens were generally considered aberrant, and the name largely disappeared from the literature by 1910. Here, we report the results of morphological and genetic analyses, and detailed observations of this chat in what we now know to be the centre of its distributional range in Ruaha National Park, Tanzania. Our results suggest that all birds from west of the Eastern Arc and southern Tanzanian highlands are of the white-collared form, which we suggest should be accorded species rank and named Myrmecocichla collaris, the Ruaha Chat.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tanzania, a country of 937,062 km2, comprises a surface relief that is far more varied than most other parts of the African continent. This surface relief results in a habitat mosaic ranging from coastal forests to montane sky islands, and includes the biologically rich Eastern Arc Mountains, as well as the volcanic highlands that track the eastern fault line of the Gregory Rift (Chorowicz 2005; Burgess et al. 2007). Recent intensive fieldwork in the Tanzanian highlands has resulted in several new species discoveries from a diverse range of vertebrate taxa (e.g. birds: Bowie et al. 2004, 2005, 2009; Bowie and Fjeldså 2005; Fjeldså et al. 2006; Fjeldså and Bowie 2008; mammals: Stanley et al. 2005; Olson et al. 2008; and amphibians: Muller et al. 2005; Menegon et al. 2008).

No less important are the lower elevation (100–1,500 m) ecosystems of Tanzania. Roughly 40% of Tanzania is comprised of Miombo (Brachystegia) woodland interspersed with seasonal wetlands induced by restricted river flow. Some of these seasonal wetlands attain lake-like proportions during the rainy season and are extremely rich in birdlife. Other lowland habitats include: savanna, open grassland, riverine thickets, swamps and forest. Due to elevational relief and extensive periods of rain, many lower elevation ecosystems are difficult to access and this inaccessibility has left vast portions of Tanzania comparatively under-studied. The limited exploration of this lowland habitat patchwork that has taken place has revealed a suit of associated range-restricted, and hence little known, species including: the Kilombero Weaver Ploceus burneiri, Olive-headed Weaver Ploceus olivaceiceps, Rufous-tailed Weaver Histurgops ruficaudus, White-winged Babbling Starling Neocichla gutturalis and the recently described Red-billed Hornbill Tockus ruahae (Kemp and Delport 2002; Sinclar and Ryan 2003; see also Glen et al. 2005).

The patchwork nature of habitats has also resulted in common African species being less well-studied in Tanzania. One of these species is the White-headed Black Chat Myrmecocichla arnotti. This species is common in central Africa and its distributional range is well documented (Keith et al. 1992; Collar 2005). However, given the patchwork nature of suitable habitat for this species in the interior of Tanzania, little detailed attention has been paid to the marked plumage variation in the populations in south-central Tanzania. This variation is only apparent in female birds, where birds distributed to the west of the Eastern Arc Mountain massif differ markedly in plumage from those birds to the east of the massif. In this publication, we describe the dramatic difference in plumage pattern among populations of M. arnotti in Tanzania and, together with molecular DNA sequence data, suggest that M. arnotti in Tanzania represents two different and incompatible species.

Methods

During our bird survey expedition of October 2002 to the Isunkaviola Hills in the extreme west of Ruaha National Park at 07°48′S, 33°52′E (1,677 m asl) Susan Stolberger noticed a dramatic difference in the females of the White-headed Black Chat in this area, in comparison to nominate M. arnotti. To document this variation, one adult female and two sub-adult females were collected and study skins prepared. In addition, one sample was taken from a population 200 km west of Ruaha at Inyonga (06°48′S, 32°25′E). These specimens are deposited at the Natural History Museum, Tring. Specimens were also examined from the following institutions: Museum of Natural History, Tring (BMNH), Zoological Museum, University of Copenhagen (ZMUC), Field Museum of Natural History (FMNH), American Museum of Natural History (AMNH), Barrick Museum (MBM) and Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

Morphological methods

Vernier calipers were used to take all measurements, which included the length of the exposed culmen (from the bill tip to the base of the exposed bill on the skull), flattened wing-chord and tail-length (from the insertion point on the pygostyle to the tip of the longest feather).

Molecular methods

DNA was extracted from tissues using the DNeasy isolation kit (Qiagen, Valencia, California) following the manufacture’s animal tissue protocol, but with an overnight proteinase K digestion at 55°C. The NADH subunit 2 gene (ND2) was PCR-amplified using primers L5204 (TAACTAAGCTATCGGGCGCAT) and H6312 (CTTATTTAAGGCTTTGAAGGCC) under standard conditions. PCR products were electrophoresed on 1% agarose gels, stained with ethibium bromide and visualised under UV light. Amplicons of the appropriate length were cut out of the gel and purified. The purified product was cycle-sequenced using Big Dye terminator chemistry (Applied Biosystems) and run on an AB3100 automated DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems). Sequences were obtained from both strands of DNA for all individuals. All sequences were checked using the program Sequencher 4.7 (Gene Codes) and aligned to the chicken (Gallus gallus) mitochondrial DNA sequence to test for the presence of any insertions, deletions or stop codons. Sequences have been submitted to GenBank under accession number: HM595023-595027.

This sample was added to a dataset consisting of other Myrmecocichla arnotti samples, Myrmecocichla formicivora, and a suite of close relatives from the genera Oenanthe, Cercomela and Thamnolaea (Outlaw et al. 2010; Voelker and Bowie, unpublished data). Analyses of individual sequences were performed using maximum likelihood (ML) in PAUP*4.0b10 (Swofford 2002). We initiated ML searches from an initial neighbour-joining starting tree using the GTR + I + Γ model of sequence evolution. This analysis was allowed to run to completion. MRBAYES (Huelsenbeck and Ronquist 2001) was used to assess nodal support. Four separate runs of 2 million generations, each consisting of four Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) chains were conducted. These analyses were initiated from random trees, and the resulting trees were sampled every 100 generations, resulting in 20,000 trees per run. The first 500,000 generations (5,000 trees) from each analysis were removed as the burn-in. The remaining 60,000 trees were combined in PAUP* (Swofford 2002) and a 50% majority rule consensus tree was generated. Huelsenbeck and Ronquist (2001) suggest that any node possessing a posterior probability value of 95% or greater is well supported and we use that standard here.

Results and discussion

Geographical variation in morphology and song

In the female of M. arnotti the white of the upper breast extends to the throat and chin, while the head and neck are black. The cheeks are predominantly black but may have some diffuse white feathers. Based on our field observations of females, the white of the upper breast and throat extends over the cheeks (which can have some diffuse black feathers) and in adult females forms a complete white collar (Fig. 1). The black of the top of the head extends from the bill above the eye to the occiput.

Newly emerged young in our study area of central-western Tanzania are brownish-black and soon attain white wing-panels (Fig. 1). Males initially develop a white supercilium, a subsequent moult shortly after results in the formation of a distinctive white cap, like nominate M. arnotti. Females develop a white upper breast and throat, cheeks and the start of a collar as sub-adults. In this first plumage the white has a slight brownish tinge with some darker flecks. The black of the head extends down the back of the neck to join the mantle. Only at the end of the first moult to adult plumage does the complete white collar form and all breast, collar and most cheek areas become white (see Fig. 1).

This variation in plumage had been noted as early as 1880 when Fischer and Reichenow (1880) described Myrmecocichla leucolaema as having a white underthroat (chin) with the lower parts and sides of the head (ear coverts) also being white and hence different from all other species of Myrmecocichla known at the time. In their description, they designate the Nguru Mountains, which are part of the Eastern Arc Mountains in Tanzania, as the type locality. Unfortunately, Fischer and Reichenow (1880) did not designate a holotype, thus making it impossible to examine the exact specimen they describe. The description of leucolaema focuses on the diagnosis of white cheeks and makes no mention of a white collar. Given that our examination of specimens of arnotti indicate that white cheeks may not be a diagnostic character due to individual variation, we are unable to confidently diagnose leucolaema. Further, the Nguru Mountains are within a region where very little Miombo woodland occurs today. Instead, the region is mostly humid forest, with semideciduous forest on the western and northern slopes. Lastly, based on our observations, the Nguru Mountains are most likely encompassed by the range of the nominate race arnotti. However, we know from observing birds throughout the duration of their breeding cycle that sub-adult females of western Tanzania birds only have a partial collar which then fully develops in their second year (Fig. 1). Thus, it is also possible that Fischer and Reichenow’s (1880) description of leucolaema is referring to a sub-adult female collaris (see below).

Two years later, Reichenow (1882) described Myrmecocichla nigra var. collaris (he considered M. nigra and M. arnotii to be conspecific). Neunzig (1926) provides additional details and is thus the most complete description of the form collaris. Neunzig notes that this taxon differs from leucolaema by females having a complete white collar that stretches behind the white ear coverts further extending the white coloration of the chin and throat; both forms have white cheeks. The type locality for collaris is listed as Kakoma, and Neunzig (1926) assigned the holotype as: Museum für Naturkunde Berlin Cat No. 27329, female, which we were able to confirm still exists (Fig. 2). Neunzig further noted that, where white-collared birds were collected, female birds without the white collar were absent. In summary, we note that females of both the forms leucolaema and collaris have predominantly white cheeks but only collaris has a complete white collar. Males of the two forms appear to be identical, and do not differ in plumage from the nominate race arnotti. The type locality Kakoma is close to where we collected birds in Ruaha National Park, and the descriptions separating leucolaema from collaris appear to match our observations of plumage variation.

Since the publication of Neunzig’s (1926) paper on Myrmecocichla nigra and arnotti, scattered observations and collections have been made of the white-collared form. Surprisingly, in all cases, the conjecture has been that white-cheeked/collared birds were aberrant specimens. For example, eight specimens in the British Museum of Natural History at Tring, were observed to have white cheeks [91.6.25.1.(19.1), 1934.10.19.-55 (19.1), 1909.12.31.167. (19.1), 1947.5.29 (19), 1945.34-210 (19), 1939.5.9-18 (20), 99.3.1.92 (20), 1931.12 0.21.64 (20)]. None of these specimens had complete white collars, and, interestingly, label dates indicate that they were probably sub-adult birds taken when full plumage characteristics of collaris would not have been complete. All eight specimens were collected in south-central Tanzania, northern Zambia, and the Albertine Rift, and therefore agree with our findings of this western variation. Other interesting examples are the collection of a white-collared bird from Kagera, in the Kivu Region (AMNH 582811) of the Albertine Rift, as well as a specimen collected more recently from Lwiro, Southern Kivu Province, Democratic Republic of the Congo (FMNH 438821).

In all these instances, the variation in plumage characters were regarded as aberrant forms of nominate arnotti, probably as a consequence of white-collared forms only having been collected from the periphery of their presently known range (defined in this study; see Fig. 3 and below). In addition, all the early publications were in German (Fischer and Reichenow 1880; Reichenow 1882; Neunzig 1926), whereas the publication by Ogilvie-Grant (1908) was in English, and he considered the forms leucolaema and collaris to be synonyms of the nominate arnotti. As a consequence, both leucolaema and collaris have effectively disappeared from the modern ornithological literature. For example, there is no mention of these races in the Birds of Africa compendium (Keith et al. 1992) and they are only briefly mentioned in the generally extensive Handbook of the Birds of the World (Collar 2005); neither work makes mention of birds with white cheeks or white collars. Interestingly, in Macworth-Praed and Grant (1952), D.M. Henry illustrated the female M. arnotti arnotti with pure white cheeks. This suggests to us that he may unknowingly have used material from south-central Tanzania rather than nominate arnotti from east of the Eastern Arc divide (Figs 1 and 3).

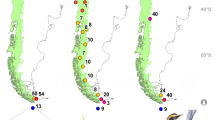

The distribution of Myrmecocichla arnotti to the east of the Eastern Arc Mountains and southern highlands (purple shading) and M. collaris to the west: 412 localities from 734 records. Note that the dots in each 0.5 × 0.5 grid cell correspond to the months in which observations were made for records from a particular grid cell, rather than an exact locality within the grid cell; see legend for further detail. The distribution of M. arnotti in the east and M. collaris in the west is coincident with the two primary blocks of Miombo woodland in Tanzania. Asterisk the putative location of the two Carnegie specimens of M. collaris we sequenced. The female was morphologically indistinguishable from M. collaris, although genetically quite divergent (3.5–5.5%). We thank the Tanzania Bird Atlas for permission to make use of this map (Neil and Elizabeth Baker, unpublished data)

The females have a loud piercing territory call but seldom sing a harmonious tune. This is in contrast to the males who will sing for hours, as an apparent form of courtship display or territorial defence. A playback experiment of nominate arnotti calls to several male collaris in Katavi National Park from as close as 15 m elicited no response. In contrast, playback of like calls elicited a rapid approach to the speaker (K. Hustler, unpublished data). Based on our detailed observations in southwestern Tanzania, examination of museum collections, the use of molecular DNA methods (see below) and song playback, we argue that the white-collared form of M. arnotti, should be considered as a valid taxon, M. collaris.

Geographical range

We have observed hundreds of the white-collared birds throughout Miombo woodland and peripheral habitats over an extensive study area in southwestern Tanzania (Fig. 3). At no time have any nominate M. arnotti been observed to the west of the Eastern Arc Mountains in Tanzania by us (the mountainous ridgeline running NE-SW in Fig. 3). In addition, surveys conducted as part of the Tanzania Bird Atlas (coordinated by Neil and Liz Baker; Fig. 3) have made many observations of white-collared birds over a large area of Miombo 200–300 km west of Ruaha National Park, and on no occasion did they observe nominate M. arnotti.

With the present information and locality records from museum specimens and observational databases, it is evident that M. collaris covers the expansive area of Tanzania which includes the Ruaha and Katavi National Parks, and the Tabora, Rukwa and Kigoma districts as well as a broader distribution that includes the extreme eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo, Akagera National Park Region of Rwanda (Peter Ryan, personal communication), Burundi (although records are very rare), northern Zambia and possibly northern Malawi. We do not at present know where (or if) M. collaris may meet M. arnotti in northern Zambia or northern Malawi as few specimens exist from those areas and no mention is made in either The Birds of Zambia (Dowsett et al. 2008) or The Birds of Malawi (Dowsett-Lemaire and Dowsett 2006) of the plumage variation in females as we report above. Establishing if these two forms do occur in sympatry should be a priority for future research.

Molecular data

Both individuals sequenced from the Isunkaviola Hills, Ruaha National Park, Tanzania, had identical mtDNA sequences, and were very similar (0.62% uncorrected-P distance) to a morphologically similar-looking bird collected in Lwiro, Southern Kivu Province, Democratic Republic of the Congo (FMNH 438821). These samples formed a reciprocally monophyletic group in maximum likelihood analyses (not shown). One bird of the nominate race M. arnotti arnotti collected from southern Malawi (MBM 11639) differed by 3.6% from our samples collected in Ruaha National Park, as well as from the bird collected at Lwiro near Lake Kivu (also 3.6%).

We also sequenced toe-pads from two museum specimens (Carnegie Museum 146903 and 146922) that were collected from 65–80 km east of Kongwa, Dodoma District, Tanzania (ca. 06°25′S, 36°15′E; Fig. 3), which is on the western side of the Ukaguru Mountains and just south of the town of Mpwapwa (see Fig. 3). The female bird (146903) is morphologically indistinguishable from our Ruaha birds and the Field Museum bird from near Lake Kivu. However, the two Carnegie birds differ by between 3.5–5.5% from the neighbouring Ruaha birds and by 2.4–3.3% from the nominate form collected in southern Malawi. Based on present field surveys, no chats have been observed within this part of the Dodoma District in the recent past. Therefore, there was either a resident population/taxon in this area (which the DNA data suggest) or the locality may be incorrect for the two Carnegie Museum birds mentioned above. At present, we cannot determine which of the above hypotheses are correct, but given the morphological similarity, and that these birds occur on the western side of the Eastern Arc Mountains, we provisionally place this locality as an outlier of the range of M. collaris.

Re-description of Myrmecocichla collaris

We have been able to compare our specimens from western Tanzania with the type of M. collaris (Museum für Naturkunde in Berlin No. 27329; Fig. 2), and confirm that the morphological variants we have observed match this form. Below, we make reference to the type and describe the recently collected specimens as paratypes.

Holotype: Museum für Naturkunde Berlin, Cat. No. 27329, adult female collected by R. Böhm on the 19 March 1881, at Kakoma, Tanzania. Wing: 97 mm. Tail: 67 mm (measurements from Neunzig 1926). Description based on Reichenow 1882; Neunzig 1926; overall appearance (based on photos of the specimen; Fig. 2) matches our description of paratype BMNH 2010.12.1.

Paratype: BMNH 2010.12.1, adult female collected by R. Glen on 8 November 2003 from Isunkaviola Hills (07°48′S, 33°52′E), Ruaha National Park, Tanzania, at 1,605 m asl. Adult female with complete white collar. Ovary not enlarged. Skull fully ossified. Weight: 20 g. Wing-chord (flattened): 90.8 mm. Tarsus: 30 mm. Culmen: 15.4 mm. Tail: 71 mm. Bill: black. Palate: black. Eye: dark red-brown. Feet: black. Stomach contents: ants and other fine insect remains.

From forehead above eye to occiput black. Below eye, cheeks, hind-neck collar, throat and upper breast, white. Some terminal black tips to feathers on throat and at the lower edge of white breast. White upper breast and throat extend 38.5 mm from bill. Below lower edge of white breast, black feathers with white centers forming spots extending towards the end of the thoracic region, 16.5 mm. Lower chest, abdomen and under-tail coverts, black. Mantle black with a few random and very fine white edges. Lesser and median coverts white, with terminal white tips. Tertials black. Primaries and secondaries brownish-black. Rump and tail black.

Paratype: BMNH 2010.12.2, sub-adult female collected by R. Glen on 3 December 2005, 10 km west of Makinde in Ruaha National Park (07°42′S, 34°28′E) at 1,450 m asl. Ovary not enlarged. Skull not fully ossified. Weight: 29 g. Wing-chord (flattened): 92.4 mm. Tarsus: 28.1 mm. Culmen: 16.2 mm. Tail: 71 mm. Bill: black. Palate: black. Eye: dark brown. Feet: black. Stomach contents: entirely small black ants.

From forehead, through eye, occiput and mantle dark sooty brown. Cheeks, throat to upper breast, white. Cheeks with some dark streaks and some white feathers beginning to appear on hind neck. White of throat extends from under the bill to upper breast, 31.7 mm. Entire underside and under-tail coverts brownish black. Lesser and median coverts white with black tips on leading feathers. Primaries and secondaries dark brown. Tail brownish black.

Paratype: BMNH 2010.12.3, sub-adult female collected by R. Glen on 3 December 2005, 10 km west of Makinde in Ruaha National Park (07°42′S, 34°28′E) at 1,450 m asl.

Ovary not enlarged. Skull not fully ossified. Weight: 32.4 g. Wing-chord (flattened): 97.2 mm. Tarsus: 32.1 mm. Culmen: 19.5 mm. Tail: 75 mm. Bill: black. Eye: dark brown. Feet: black. Stomach contents: small black ant remains.

Forehead through eye to occiput, sooty black. Throat to upper breast, cheeks and collar white. Some black feather bases are flecked on the throat. White on under throat to upper breast extends down 37 mm. Some white centered black feathers extending as spots, 20 mm below white upper breast. Lesser and median coverts white with black terminal tips. Rest of underside including undertail coverts and tail black. Mantle black. Primaries and secondaries brownish-black.

Paratype: BMNH 2010.12.4, sub-adult male collected by R. Glen on 4 September 2005, 30 km east of Inyonga (06°43′49″S, 32°03′40″E), Rukwa Region, Tanzania at 1,192 m asl. Testes not enlarged. Skull not fully ossified. Weight: 32.5 g. Wing-chord (flattened): 97.8 mm. Tarsus: 30 mm. Culmen: 14.2 mm. Tail: 68.5 mm. Bill: black. Palate: Black. Eye: dark brown. Feet: black. Stomach contents: ant remains and one cricket.

Forehead to occiput, over eye, white. White not solid but some black feather bases showing. Lesser and median coverts white with black terminal tips. Otherwise, complete upper parts, underside, primaries and secondaries black with brown tinge. Tail: black.

Natural history observations of Myrmecocichla collaris

Two breeding seasons occur at the breeding site located within the Isunkaviola Hills of Ruaha National Park, Tanzania (April–May and October–November). Nesting locations are at least 200 m apart in mature Miombo woodland (Brachystegia) and are at least 500 m apart in peripheral woodlands. Young are incubated and fed from a nest located within a nest hole in a tree 1–4 m above the ground.

In a given year, young from both breeding seasons remain in the territory together with the adult pair until the next season. During this period, all individuals are involved in group-feeding and are vocal. Birds spend a considerable amount of time hawking insects. During feeding, they will always take a small hop forwards, bow the head with tail up, and flick the wings. If there is high food availability, it appears that female birds will typically not feed at the same time as the males, or will feed apart. The females seem to chase off the young males if the young males do not observe this feeding practice. The adult male will always fly off if the female arrives and vice versa. Why they exhibit this behaviour is not at present known.

Conclusions

As is often the case, the differences we report in female collaris plumage (males are not distinguishable in plumage) have simply been overlooked. From our observations, all the birds east of the eastern Arc Massif and southern highlands are of nominate M. arnotti, while all the birds observed west of the mountain divide are of the white-collared form, which we suggest should be accorded species rank and named M. collaris. We suggest the vernacular name Ruaha Chat.

Zusammenfassung

Regionale Gefiedervariationen zwischen Populationen der Arnott-Schmätzer (Myrmecocichla arnotti) in Tanzania bestätigen die Rasse ‘collaris’ als eigenständiges Taxon

In den letzten 30 Jahren wurde in Tansania eine bemerkenswerte Zahl neuer Wirbeltierarten entdeckt. Diese Entdeckungen wurden hauptsächlich in den bergigen Regionen gemacht, besonders in den ‚Eastern Arc Mountains’. Unlängst haben Untersuchungen im schwer erreichbaren Inland Tansanias eine einzigartige Vogelfauna mit einigen endemischen Taxa enthüllt. Eines dieser endemischen Taxa ist die Rasse ‘collaris’ beim Arnott-Schmätzer. Nachdem die Rasse ‘collaris’ von Reichenow im Jahre 1882 erstmals beschrieben wurde, hat sich gezeigt, dass sich diese durch einen komplett weißen Kragen bei den Weibchen von der Nominatform morphologisch unterscheidet. Aufgrund mangelnden Wissens über die Entwicklung des adulten Gefieders, des Verbreitungsgebietes und mangelnder Erkennungsmerkmale der Männchen der verschiedenen Arnott-Schmätzer Rassen, wurde ‘collaris’ meist nicht anerkannt und der Name verschwand nach 1910 aus der Literatur. In diesem Artikel werden die Ergebnisse der morphologischen und genetischen Untersuchungen und eingehender Beobachtungen dieses Schmätzers im Zentrum seines Verbreitungsgebietes, Ruaha National Park in Tansania, beschrieben. Die Ergebnisse zeigen, dass alle Vögel westlich der ‚Eastern Arc Mountains’ und südlich des Hochlandes Tansanias zu der Weißkragen-Form gehören, welche unserer Meinung nach als eigene Art anerkannt werden sollte, mit dem Namen Ruahaschmätzer Myrmecocichla collaris.

References

Bowie RCK, Fjeldså J (2005) Genetic and morphological evidence for two species in the Udzungwa Forest Partridge Xenoperdix udzungwensis. J East Afr Nat Hist 94:191–201

Bowie RCK, Fjeldså J, Hackett SJ, Crowe TM (2004) Systematics and biogeography of double-collared sunbirds from the Eastern Arc Mountains, Tanzania. Auk 121:660–681

Bowie RCK, Voelker G, Fjeldså J, Lens L, Hackett SJ, Crowe TM (2005) Systematics of the Olive Thrush Turdus olivaceus species complex with reference to the taxonomic status of the endangered Taita Thrush T. helleri. J Avian Biol 36:391–404

Bowie RCK, Fjeldså J, Kiure J (2009) Multilocus molecular DNA variation in Winifred’s Warbler Scepomycter winifredae suggests cryptic speciation and the existence of a threatened species in the Rubeho-Ukaguru Mountains of Tanzania. Ibis 151:709–719

Burgess ND, Butynski TM, Cordeiro NJ, Doggart NH, Fjeldså J, Howell KM, Kilahama FB, Loader SP, Lovett JC, Mbilinyi B, Menegon M, Moyer DC, Nashanda E, Perkin A, Rovero F, Stanley WT, Stuart SN (2007) The biological importance of the Eastern Arc Mountains of Tanzania and Kenya. Biol Conserv 134:209–231

Chorowicz J (2005) The East African rift system. J Afr Earth Sci 43:379–410

Collar N (2005) Family Turdidae (Thrushes). In: del Hoyo J, Elliot A, Christie DA (eds) Handbook of the birds of the world, vol 10. Lynx, Barcelona, pp 514–807

Dowsett RJ, Aspinwall DR, Dowsett-Lemaire F (2008) The birds of Zambia. Tauraco Press and Aves

Dowsett-Lemaire F, Dowsett RJ (2006) The birds of Malawi. Tauraco Press and Aves

Fischer, Reichenow A (1880) Neue vögel aus Ost-Afrika. Ornithologisches Centralblatt

Fjeldså J, Bowie RCK (2008) New perspectives on the origin and diversification of Africa’s forest avifauna. Afr J Ecol 46:235–247

Fjeldså J, Bowie RCK, Kiure J (2006) The Forest Batis, Batis mixta, is two species: description of a new, narrowly distributed Batis species in the Eastern Arc biodiversity hotspot. J Ornithol 147:578–590

Glen R, Mthaiko M, De Leyser L, Stolberger S (2005) Bird records from the Isunkaviola Hills Ruaha National Park, Tanzania. Scopus 25:61–66

Huelsenbeck JP, Ronquist F (2001) MrBayes: Bayesian inference of phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics 17:754–755

Keith SE, Urban K, Fry CH (1992) The Birds of Africa: Vol. 4. Broadbills to Chats. Academic, London

Kemp AC, Delport W (2002) Comments on the status of subspecies within the Red-billed Hornbill Tockus erythrorhynchus complex (Aves: Bucerotidae), with description of a new taxon endemic to Tanzania. Ann Transvaal Museum 39:1–8

Macworth-Praed CW, Grant CH (1952) Birds of East Africa. Butler and Tanner, London

Menegon M, Doggart N, Nisha O (2008) The Nguru Mountains of Tanzania, an outstanding hotspot of herpetofaunal diversity. Acta Herpetol 3:107–127

Muller H, Measey GJ, Loader SP, Malonza PK (2005) A new species of Boulengerula Tornier (Amphibia: Gymnophiona: Caeciliidae) from an isolated mountain block of the Taita Hills, Kenya. Zootaxa 1004:37–50

Neunzig R (1926) Die formenkreise Myrmecocichla nigra und arnotti. J Ornithol LXXIV:749–755

Ogilvie-Grant WR (1908) On a collection of birds made by Mr. Douglas Curruthers during his journey from Uganda to the mouth of the Congo. Ibis 50:264–317

Olson LE, Sargis EJ, Stanley WT, Hildebrandt KBP, Davenport TRB (2008) Additional molecular evidence strongly supports the distinction between the recently described African primate Rungwecebus kipunji (Cercopithecidae, Papionini) and Lophocebus. Mol Phylogenet Evol 48:789–794

Outlaw RK, Voelker G, Bowie RCK (2010) Shall we chat? Evolutionary relationships in the genus Cercomela (Muscicapidae) and its relation to Oenanthe reveals extensive polyphyly among chats distributed in Africa, India and the Palearctic. Mol Phylogenet Evol 55:284–292

Reichenow A (1882) Neue arten aus Ost-Afrika. J Ornithol XXX:211–212

Sinclar I, Ryan PG (2003) Birds of Africa south of the Sahara. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Stanley WT, Rogers MA, Hutterer R (2005) A new species of Congosorex from the Eastern Arc Mountains, Tanzania, with significant biogeographical implications. J Zool (Lond) 265:269–280

Swofford D (2002) PAUP* 4.0. Phylogenetic analysis using parsimony* and other methods. Sinauer, Sunderland

Acknowledgments

We thank Sylke Frahnert (Museum für Naturkunde Berlin), Robert Prys-Jones and Mark Adams (Museum of Natural History, Tring), Paul Sweet (American Museum of Natural History), David Willard, John Bates and Shannon Hackett (Field Museum of Natural History), John Klicka (Barrick Museum), Stephen Rogers (Carnegie Museum of Natural History) and Jon Fjeldså (Zoological Museum, Copenhagen) for loan of specimens and tissues, and their willingness to take photographs of key specimens for our use. Christine Giannoni from the Field Museum library provided invaluable help in sourcing and scanning some rare old manuscripts for our use. We thank TANAPA (Tanzania National Parks) and Ruaha National Park for allowing our long-term observation of chats in Ruaha National Park and for permission to collect the specimens described in this paper. Special thanks to Neil and Liz Baker who freely offered their knowledge of the distribution of the two forms of chat in Tanzania and to all the contributors to the Tanzania Bird Atlas who reported the plumage variation and shared an interest in the results of this study. We thank Jon Fjeldså for his comments on an earlier version of this manuscript that greatly helped to improve it. The laboratory work was funded by National Science Foundation grant DEB0613668 to G.V. and R.C.K.B. This is publication number 1221 of the Texas Cooperative Wildlife Collection and number 181 of the Center for Biosystematics and Biodiversity, both at Texas A&M University. All experiments comply with the current laws of the Republic of Tanzania.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by J. Fjeldså.

R. Glen and R. C. K. Bowie contributed equally to this work.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Glen, R., Bowie, R.C.K., Stolberger, S. et al. Geographically structured plumage variation among populations of White-headed Black Chat (Myrmecocichla arnotti) in Tanzania confirms the race collaris to be a valid taxon. J Ornithol 152, 63–70 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-010-0548-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-010-0548-2