Abstract

Global navigation satellite system (GNSS) remote sensing of the troposphere, called GNSS meteorology, is already a well-established tool in post-processing applications. Real-time GNSS meteorology has been possible since 2013, when the International GNSS Service (IGS) established its real-time service. The reported accuracy of the real-time zenith total delay (ZTD) has not improved significantly over time and usually remains at the level of 5–18 mm, depending on the station and test period studied. Millimeter-level improvements are noticed due to GPS ambiguity resolution, gradient estimation, or multi-GNSS processing. However, neither are these achievements combined in a single processing strategy, nor is the impact of other processing parameters on ZTD accuracy analyzed. Therefore, we discuss these shortcomings in detail and present a comprehensive analysis of the sensitivity of real-time ZTD on processing parameters. First, we identify a so-called common strategy, which combines processing parameters that are identified to be the most popular among published papers on the topic. We question the popular elevation-dependent weighting function and introduce an alternative one. We investigate the impact of selected processing parameters, i.e., PPP functional model, GNSS selection and combination, inter-system weighting, elevation-dependent weighting function, and gradient estimation. We define an advanced strategy dedicated to real-time GNSS meteorology, which is superior to the common one. The a posteriori error of estimated ZTD is reduced by 41%. The accuracy of ZTD estimates with the proposed strategy is improved by 17% with respect to the IGS final products and varies over stations from 5.4 to 10.1 mm. Finally, we confirm the latitude dependency of ZTD accuracy, but also detect its seasonality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The global navigation satellite system (GNSS) signal delay depends on pressure, temperature, and water vapor content along the propagation path, which creates a link between GNSS and meteorology. Although troposphere delay is treated as an error source in precise GNSS positioning, there is a great potential of exploiting troposphere delays for weather and climate monitoring (Bianchi et al. 2016; Guerova et al. 2016). This is because the tropospheric wet delay is representative of the quantity of water vapor integrated along the signal path. As a result, the tropospheric delay estimates from GNSS measurements can be used to quantify the precipitable water (PW, in [mm]) or its equivalent—integrated water vapor (IWV, in [kg/m2]), using other well-determined meteorological data, i.e., pressure and temperature (Lee et al. 2013; Shi et al. 2015a).

GNSS remote sensing of the troposphere, called GNSS meteorology (Tralli and Lichten 1990; Bevis et al. 1992), provides observations with spatial and temporal resolutions that are higher than any other tropospheric sensing technique and operates in all weather conditions (Bennitt and Jupp 2012). Post-processing of GNSS observations can provide results with accuracies comparable to measurements of traditional precipitable water vapor sensors (Rocken et al. 1997; Haase et al. 2003; Satirapod et al. 2011). The main product of GNSS meteorology, the zenith total delay (ZTD), can be assimilated into numerical weather prediction (NWP) models, which leads to better initial states and thus improves the quality of forecasts, especially during severe weather conditions (Cucurull et al. 2004; Yan et al. 2009; De Haan 2013). In Europe, the E-GVAP project (https://egvap.dmi.dk/) was established for monitoring water vapor on a European scale with GNSS in near real time (latency < 90 min) for meteorological use (Elgered et al. 2005; Vedel et al. 2013). The reported accuracy of ZTD estimates from near real-time GPS data processing is 3–10 mm (Pacione et al. 2009; Douša and Bennitt 2013; Hadas et al. 2013) and products are usually delivered with a temporal resolution between 5 and 30 min. The threshold accuracy of ZTD products for NWP assimilation is 15 mm, while a target value of 10 mm is preferable (E-GVAP 2010; Dymarska et al. 2017).

The timely provision of GNSS ZTD estimates is limited by the latency of information for precise satellite orbits and clocks. New possibilities for GNSS meteorology became feasible in 2013, when the International GNSS Service (IGS) established its real-time service (RTS, https://www.igs.org/rts). A standard deviation of 5 to 18 mm for ZTD from real-time GPS data processing was early reported by Douša and Václavovic (2014), Li et al. (2014) and Yuan et al. (2014). The obtained accuracy is depending on the station and period are being studied; therefore, it is sensitive to weather conditions. A strong correlation could be noticed between the precision of the real-time satellite clock products and the real-time GPS ZTD solutions using the precise point positioning (PPP) technique (Shi et al. 2015b). Several real-time ZTD estimation software packages were compared by Ahmed et al. (2016), who noticed a major decrease in the accuracy when ignoring antenna reference point eccentricities and phase center offsets and variations. The improvement of ZTD estimation from integer ambiguity fixing was at the millimeter level only (Ahmed et al. 2016; Ding et al. 2017; Lu et al. 2018). Li et al. (2015) and Lu et al. (2015) reported significantly worse accuracy of real-time ZTD from GLONASS-only and BeiDou-only processing compared to GPS-only processing. Compared to GPS-only processing, GPS + GLONASS and multi-GNSS processing with empirical weighting factors obtained using variance component estimation method led to a ZTD accuracy improvement of up to 10 and 22%, respectively (Lu et al. 2017; Douša et al. 2018). Pan and Guo (2018) noticed that the retrieval accuracy of real-time ZTDs is latitude dependent due to varying water vapor contents in different latitude regions. Pan and Guo (2018) and Zhao et al. (2018) considered tropospheric azimuthal asymmetry, which only slightly improved the ZTD retrieval accuracy. However, horizontal gradients are sensitive to processing options and providing real-time gradients would require multi-GNSS constellation with high-accuracy real-time products (Kačmařík et al. 2019). Yuan et al. (2019) recommend using forecasted Vienna mapping functions 1 (VMF1-FC) for ZTD modeling in real-time GNSS applications.

Although some aspects of a ZTD retrieval in real time have already been investigated independently, the reported accuracy did not improve over time significantly. The real-time campaign of the European Cooperation in Science and Technology (COST) Action GNSS4SWEC (advanced global navigation satellite systems tropospheric products for monitoring severe weather events and climate, https://gnss4swec.knmi.nl/) revealed that further research is still required (Jones et al. 2020). However, neither are these achievements combined in a single processing strategy, nor is the impact of other processing parameters on ZTD accuracy analyzed, e.g., the choice of PPP functional model, GNSS selection and combination, inter-system weighting, and elevation-dependent weighting function when using low elevation observations. Therefore, the presented results can be blurred by the non-optimal selection of other processing parameters. Moreover, results from multi-GNSS processing should be reviewed, due to recent improvements in Galileo’s space segment (Steigenberger and Montenbruck 2017; Chatre and Verhoef 2018) and progressing advances in GNSS orbit and clock modeling, including real-time products (Kazmierski et al. 2018b). It should be noted that, among the quoted papers, studies on real-time ZTD retrieval using multi-GNSS observations cover data analysis up to early 2017. Therefore, not only a former reference frame and antenna calibration models were applied, but also an immature Galileo constellation was used. Since early 2019, the Galileo constellation is almost complete, and the accuracy of Galileo-only real-time positioning is close to GPS-only positioning (Hadas et al. 2019). Therefore, not only a significant contribution of Galileo observations in a multi-GNSS solution is expected, but it is also possible to investigate single system real-time ZTD retrieval from all four GNSSs.

We investigate the sensitivity of real-time troposphere products on various processing parameters, i.e., PPP functional model, GNSS selection and combination, inter-system weighting, elevation-dependent weighting function, and gradient estimation. We define an advanced strategy dedicated to real-time GNSS meteorology, which combines recommended processing parameters. We evaluate the accuracy of real-time ZTD by comparing real-time products with the final IGS product and ZTD obtained from ray-tracing through a selected NWP.

Methodology

In the following subsections, we describe the test period and stations, provide sources of all data and products, introduce functional models of GNSS data processing and define the processing strategy with multiple variants.

Data and products

We select two test periods, both covering 31 consecutive days of observations. The winter test period starts on January 1, 2019 (day of year, DoY 1) and the summer test period starts on June 2 (DoY 183), 2019. For the evaluation of ZTD accuracy, we extend the test period to the entire year 2019.

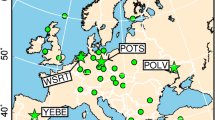

We use RINEX 3.0 × files from 20 globally distributed IGS stations of varying altitudes (Fig. 1). Among selected stations are 10 different receiver types from 4 different manufacturers and 12 different antenna types from 6 manufacturers. Stations ALGO and BIKO track GPS, GLONASS, and Galileo, station REYK tracks also BeiDou during the second test period, while the other 17 track all four GNSS during both periods. The antenna at station KERG misses GLONASS phase center offset (PCO) and variation (PCV) calibrations in the up-to-date igs14.atx ANTEX file. None of the antennas has PCO/PCV calibration for Galileo and BeiDou.

We use BKG’s Ntrip Client v 2.12 to record real-time broadcast ephemeris from the real-time service (RTS, https://www.igs.org/rts) stream RTCM3EPH and to store real-time multi-GNSS orbit and clock corrections, which are provided by the Centre National d’Études Spatiales (CNES) through CLK93 stream.

We use the official IGS final estimates, delivered by United States Naval Observatory (USNO) as a reference product for ZTD. The temporal resolution of the product is 5 min. Moreover, ZTD is modeled from the global forecast system (GFS) fields provided by U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration/National Centers for Environmental Prediction (NOAA/NCEP). ZTDs are derived by integrating vertical profiles of refractivity, which are interpolated from 0.5° × 0.5° horizontal grid using inverse distance weighting. Refractivity profiles are up-sampled to a high-resolution vertical grid (about 1 m in the troposphere) by cubic splines before computing ZTD from the numerical integration. Station-specific ZTDs are determined for predefined station location and attitude. A more detailed description of this procedure can be found in Kačmařík et al. (2017).

Functional model

We use the GNSS-WARP software (Hadas 2015) to process multi-GNSS, multi-frequency pseudorange (code) \(P\), and carrier phase \(L\) observations using the PPP technique. The data are processed using the standard ionospheric-free (IF) observation model (Malys and Jensen 1990; Zumberge et al. 1997) and undifferenced uncombined model (Schönemann 2014).

The standard ionospheric-free observation model is defined as:

with

where \(s\) denotes the satellite number and \(S\) is the corresponding GNSS (\(S \in \left\{ {G,R,E,C} \right\}\) for GPS, GLONASS, Galileo, and BeiDou, respectively); \(\rho_{0}^{s}\) is the geometric distance between the position of the satellite s antenna phase center \(\left( {X^{s} ,Y^{s} ,Z^{s} } \right)\) and the a priori position of the receiver r antenna phase center \(\left( {X_{r} ,Y_{r} ,Z_{r} } \right)\); c is the speed of the light; \(\delta t^{s}\) and \(\delta t_{r}\) are satellite and receiver clock offsets, respectively; \(m_{h}^{s}\) and \(m_{w}^{s}\) are the hydrostatic and wet mapping function, respectively; \(Z_{h}\) and \(Z_{w}\) are the zenith hydrostatic and wet delay, respectively; \(\Delta_{P}^{s}\) and \(\Delta_{L}^{s}\) are satellite, receiver, and site displacement effect corrections (Gérard and Luzum 2010) for pseudoranges and carrier phase measurements, respectively; e is the direction vector; \(\delta X\) is the position correction vector; \({\text{ISB}}_{S}^{G}\) is the receiver inter-system bias between \(S\) and \(G\) (for \(S = G\), it is set to 0); \(\lambda_{{{\text{IF}}}}^{s}\) is the ionospheric-free wavelength; \(B_{{{\text{IF}}}}^{s}\) is the ionospheric-free ambiguity (bias) parameter; \(i\) is the number of the frequency \(f\).

The undifferenced uncombined processing is performed using the following observation model:

Compared to the ionospheric-free model, in the undifferenced uncombined model pseudorange and carrier phase observations are processed unchanged. This requires the estimation of slant ionosphere delays \(I^{s}\) and allows estimating ambiguities \(N_{i}^{s}\) corresponding to their original wavelength \(\lambda_{i}\).

Horizontal gradients are estimated as random walk variables with a process noise an order of magnitude smaller than for ZTD. The gradient contribution term that has to be additionally included on the right-hand side of (1, 2, 7 and 8) is:

where \(G_{N}\) and \(G_{E}\) are horizontal components (north and east direction) of a tropospheric gradient, \(a\) is the azimuth, \({\text{mf}}^{G}\) is an elevation \(e\)-dependent gradient mapping function and can be expressed as (Chen and Herring 1997):

Alternative mapping functions are proposed and studied in great detail by MacMillan (1995) and Masoumi et al. (2017).

Strategy and variants

We surveyed all papers mentioned in the introduction which focus on real-time ZTD estimation, in order to identify the most popular settings of a processing strategy. In this way, a common processing strategy is defined (Table 1). This strategy is further modified in many ways, changing the following aspects: observation model, GNSS selection and inter-system weighting, elevation-dependent weighting, gradient estimation. In addition to the common solution, 11 alternative solutions are obtained (Table 2).

Differences between real-time results

Through a comparison of results obtained with the different processing strategies, we identify the significance and impact of selected processing parameter on real-time ZTD product. As a consequence, we define an advanced strategy for real-time ZTD estimation.

Observation model

The ZTD differences obtained for all test stations with ionospheric-free and undifferenced uncombined functional models are zero mean with the standard deviation smaller than 2.0 mm (Fig. 2). Detailed insights into the results reveal that extreme differences occur during the initialization of a PPP solution. They are also caused by slight differences that occur during the rejection of observation outliers. Therefore, the choice of the functional model is less critical, unless additional data are used, e.g., third frequency or ionosphere model. In such a case, the undifferenced uncombined model is recommended, as it allows to include ionospheric constraints (Banville et al. 2014) and is the key for efficient phase ambiguity resolution (Shi et al. 2015b). The model allows us to process multi-frequency data. However, such processing for precise applications would require antenna calibration information for all signals. Otherwise, missing PCO or PCV corrections may dramatically degrade the accuracy of estimated ZTD (Ahmed et al. 2016).

Single GNSS solution

Not only GPS, but also GLONASS, Galileo, and BeiDou are already mature enough to provide independent solutions themselves. A real-time PPP solution is limited by the accuracy and availability of real-time orbit and clock correction. The CLK93 stream supports all GPS and GLONASS satellites. For Galileo, the two satellites on elliptical orbits (E14 and E18) are not supported, due to missing navigation messages (Steigenberger and Montenbruck 2017). For BeiDou, the corrections are provided only for second-generation satellites.

During both test periods, the availability of real-time corrections varies among systems and is the largest for GPS, and the smallest for BeiDou (Fig. 3). For GPS and GLONASS, there are some incidents with missing corrections during both test periods. During the winter test period, the latest four Galileo satellites are not supported yet. For BeiDou, corrections are frequently missing during both periods, sometimes even for the entire constellation. There are few episodes with missing corrections for all GNSSs (DoY 10, 31, 200, and 206, 2019) due to a failure of the Internet connection at the user side. However, a similar episode at DoY 207, 2019 is caused by the stream provider.

Due to different numbers of satellites per constellation, varying availability of real-time corrections and their inhomogeneous quality, the availability of single GNSS real-time PPP solution, hence the availability of real-time ZTD, varies (Fig. 4). For GPS, it ranges from 88.4% (KZN2, winter) to over 99.5% (8 stations in summer). For GLONASS, we notice a significant degradation of solution availability for stations located far west (FAA1, YEL2), in central and East Asia (BIK0, LHAZ, ULAB). These locations correspond to regions of low coverage of the RTS network (https://www.igs.org/network?network=rts). A small availability of Galileo-only solution for station KERG is caused by an insufficient number of observations at the E5a frequency. For Galileo, the average availability over both periods is similar. However, the second period was affected by the Galileo outage episode, which caused a 5-day-long unavailability of real-time solutions. Neglecting this episode, the estimated availability of Galileo-only solution would increase from 73.2 to over 87%. Therefore, the inclusion of four newest satellites in CLK93 stream was a major step for the performance of Galileo-only real-time PPP. The BeiDou-only solution is almost unavailable for stations on the Western Hemisphere. However, we can identify that there are BeiDou-only solutions for some high-latitude stations (YEL2, REYK, WROC, RDGD), which can also receive low-elevation signals from satellites located either on geostationary (GEO) or inclined geosynchronous orbit (IGSO). Solution availability grows the further east a station is, reaching a maximum of 49.1% and 50.0% for station PNGM during the winter and summer test periods, respectively.

We notice that time series of real-time ZTD obtained with various single GNSS solutions are quite consistent with each other, except often outlying BeiDou-only solutions (Fig. 5). The best agreement with the GPS-only solutions, by means of the correlation coefficient and the RMSE of ZTD differences, is found for Galileo-only solution (Table 3). Although none of the GNSS outperforms GPS by means of solution availability, a high consistency of GLONASS-only and Galileo-only solutions with GPS-only solution, expressed by the RMSE of ZTD differences below 10 mm, shows, that they can provide independent and reliable ZTD product if only the real-time corrections availability increases. For BeiDou, this should also be achieved when the third generation of satellites will be supported in the RTS.

Multi-GNSS solution

A combination of observations from four GNSSs in a multi-GNSS solution creates a tool that traces the troposphere with an outstanding resolution. Compared to a single GNSS solution, in multi-GNSS mode, the number of observations is at least twice as much (Fig. 6). However, as real-time product accuracy varies for different GNSS, this requires careful weighting of observations in a multi-GNSS solution. A multi-GNSS solution with equal weighting, compared to a GPS-only solution, either improves or degrades the internal accuracy of the adjustment, expressed by an average a posteriori error of unit weight (Fig. 7). On the other hand, for multi-GNSS solutions with inter-system weighting applied (Kazmierski et al. 2018a), there is an improvement from 7 to 37% (23% on average).

Differences of real-time ZTD between a GPS-only and a multi-GNSS solution reach up to 30 mm for a solution with equal weighting but are usually below 10 mm with inter-system weighting applied (Fig. 8). In multi-GNSS solutions, ZTD is usually underestimated by few millimeters with respect to GPS-only solutions. We justify this effect by the missing receiver PCO and PCV for Galileo and BeiDou, and the adoption of corresponding values from GPS or GLONASS (Table 1).

Elevation-dependent weighting

The choice of an elevation-dependent stochastic model affects solution precision and is particularly relevant for an accurate height determination (Jin et al. 2005; Luo et al. 2014). The three most commonly used functions to calculate the standard deviation \(\sigma\) of a GNSS observation are: sine (Dach et al. 2015), sine-type (King and Bock 2001) and exponential (Euler and Goad 1991; Li et al. 2016), which are defined as follows:

where \(e\) is the elevation angle, \(\sigma_{0}\) is a priori sigma of an observation (Table 1), the constant parameters are set to: \(\alpha_{1} = 0.64\), \(\beta_{1} = 0.36\), \(\alpha_{2} = 1\), \(\beta_{2} = 3.5\), \(e_{0} = 9^\circ\). The common feature of these functions is that they significantly down weight low elevation observations. This is an adverse effect of former characteristics of GNSS antennas and troposphere mapping functions. Therefore, we propose alternative, cosine-type function

with \(\alpha_{3} = 1\), \(\beta_{3} = 4\), \(n = 8\). We test all four elevation-dependent weighting function. The weighting factor \(\sigma /\sigma_{0}\) equals to 1 for \(e = 90^\circ\), but varies significantly for lower elevation angles (Fig. 9).

We find an impact of the weighting function on coordinate precision and a posteriori error of ZTD (Table 4). Exponential weighting function performs similarly and significantly better to sine-type function during winter and summer test periods, respectively. With the cosine-type function, a significant reduction of σZTD is reached in exchange for worse horizontal precision. We justify this as an impact of very low-elevation observations. The choice of weighting function causes differences in estimated ZTD (Fig. 10), which usually remain below 5 mm level, but may exceed 10 mm during initialization periods.

Gradient estimation

The magnitude and direction of estimated real-time tropospheric gradients vary over time and stations (Fig. 11). We usually observe smaller magnitudes for inland stations than we do for coastal and island stations. For both test periods, the gradients are close to zero mean and the clear effect of the atmospheric bulge, i.e., the diurnal variations of density of the neutral gas, is not observed. The a posteriori standard deviation of estimated gradients is usually within the range of 0.1 to 0.3 mm. Moreover, the a posteriori error of unit weight is reduced by 23% on average and the receiver height precision is improved by 27% on average, compared with a solution neglecting troposphere gradients.

The estimation of tropospheric gradients has an impact on the estimated ZTD (Fig. 12). ZTD differences between solutions with and without gradient estimation exceed 10 mm in extreme cases, e.g., after solution initialization, but are usually smaller than 2–5 mm, depending on a station. The larger a gradient magnitude is, the larger a corresponding ZTD difference can be, but also large magnitude gradients can have a small impact on ZTD. This means that other estimated parameters, i.e., receiver clock error or height, can absorb this effect.

Advanced strategy

Following the abovementioned results, a state-of-the-art strategy for real-time ZTD determination with GNSS should differ from the common approach (Table 1). The recommended strategy is based on the undifferenced uncombined functional model, applies inter-system weighting for multi-GNSS observations, uses elevation-dependent cosine-type weighting function and estimates horizontal gradients.

We notice significant differences in ZTD between the two strategies. The advanced strategy allows reducing the average a posteriori error of estimated ZTD (Fig. 13). The reduction varies from 10% for station KERG to 53% for station CAS1 during the winter test period, and from 13% for station JPLM to 50% for station RGDG during the summer test period. The ZTD differences between both strategies usually remain within ± 10 mm range but reach up to 50 mm during the initialization period or limited availability of RTS corrections (Fig. 14). We find an average offset between the two solutions, which equals -2.6 mm and − 2.0 mm for winter and summer test periods, respectively. All of this confirms that significant differences can be found in ZTD depending on the processing strategy, as the optimal accuracy for ZTD should be 5 mm (https://egvap.dmi.dk/support/formats/egvap_prd_v10.pdf).

Accuracy of real-time ZTD

We assess the consistency of ZTD from the two reference products. Then, the accuracy of ZTD obtained with the advanced strategy is compared against the accuracy of results obtained with the common processing strategy.

Assessment of reference products

The agreement between ZTD from the two reference products depends on the station and time (Fig. 15). Although the general variability of ZTD is reflected in both products, major differences between the two products are also present. The smallest standard deviation of ZTD differences over the entire year 2019 is 5.1 mm for station CAS1, the largest is 22.4 mm for station BIK0. On average, the standard deviation of ZTD differences is 12.7 mm, which agrees with (Lu et al. 2016). Moreover, we notice incidental large peaks and frequent midnight discontinuities in the time series of the final ZTD, which exceed 10 mm. This is far more than the 2–3 mm uncertainty, which is reported for the IGS final ZTD and questions the few-millimeter-level precision of this product.

Validation of real-time products against reference products

When comparing to the IGS final product (Fig. 16, top), the standard deviation of ZTD differences is reduced in the advanced strategy for all stations by 11% on average. The multi-GNSS product is underestimated with respect to the GPS-only product, resulting in a smaller average offset with respect to the IGS final product. The average RMSE of ZTD differences improves from 9.5 mm in the common strategy to 7.9 mm in the advanced strategy (17%) over the entire year 2019. When comparing against the GFS model (Fig. 16, bottom) significantly higher standard deviations of ZTD differences are observed than for the comparison with the IGS products. Still the 5% of improvement is found when changing from the common strategy to the advanced strategy.

IGS final products originate from post-processing of GPS-only observations in the double-differenced mode and real-time ZTD are estimated with the PPP technique. They should not be considered as totally independent and a small bias is expected. However, midnight discontinuities of the final ZTD and a processing strategy, which was defined already several years ago, can justify the limited improvement with respect to IGS product. On the other hand, GFS is an independent source of ZTD which implies that worse consistency of real-time products with GFS can be expected. In particular, station and NWP-specific biases can occur and are justified by a deficiency of the NWP orography representation (Kačmařík et al. 2017). However, when comparing GNSS ZTD to NWP model products, a bias should not be considered as a quality indicator, because station-specific GNSS ZTD biases are removed prior to ZTD assimilation (Mile et al. 2019).

Conclusions

With a total number of 20 different real-time solutions for a worldwide spatially distributed set of stations and two time periods, we investigate the impact of PPP processing parameters on estimated ZTD. We show that for dual-frequency and ionosphere-unconstrained processing, the choice of functional model between ionospheric-free and undifferenced uncombined is not critical. We show that all four GNSSs can provide real-time ZTD solutions independently. The best agreement with GPS-only solution is found for Galileo-only solution, whereas the performance of BeiDou-only solution is the worst. We also show that a multi-GNSS solution, with inter-system weighting based on the SISRE parameter, reduces the a posteriori standard deviation of estimated ZTD by up to 37%. We propose a cosine-type elevation-dependent weighting function, which reduces the a posteriori error of estimated ZTD. We confirm that the estimation of real-time gradients improves height precision by 27% on average and can significantly affect ZTD estimates. Real-time gradients are estimated with an uncertainty of 0.1–0.3 mm, but their accuracy with respect to an NWP model or post-processing results is not investigated in this study. Based on the abovementioned conclusions, we define an advanced strategy dedicated to real-time GNSS meteorology.

We question the few millimeters accuracy of ZTD final products from the IGS, noticing centimeter-level jumps at the day boundary. The standard deviation of ZTD differences between GFS ray-tracing and IGS product exceeds 12 mm. Despite that, we compare real-time ZTD obtained with the common and advanced strategies against both reference products. The advanced strategy is superior to the common one, i.e., it has 0.9% more results over the entire year 2019, and the a posteriori error of estimated ZTD is reduced by 41% on average. The accuracy with respect to the IGS final product improves by 17% and varies over stations from 5.4 to 10.1 mm. Such performance will legitimate real-time ZTD estimates for assimilation into NWP.

Data availability

RINEX 3.0 × files and IGS final ZTD are available at public repositories: ftp://igs.bkg.bund.de, ftp://cddis.nasa.gov. NOAA/NCEP GFS forecast products can be downloaded from https://nomads.ncdc.noaa.gov/data/gfs4/. Real-time multi-GNSS orbit and clock products are available in CNES repository https://www.ppp-wizard.net/products/REAL_TIME/. The same products, but recorded directly from CLK93 stream, are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Change history

10 September 2020

In the original version of this article, equation (9) was displayed incorrectly.

References

Ahmed F, Václavovic P, Teferle FN, Douša J, Bingley R, Laurichesse D (2016) Comparative analysis of real-time precise point positioning zenith total delay estimates. GPS Solut 20(2):187–199. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10291-014-0427-z

Banville S, Collins P, Zhang W, Langley RB (2014) Global and regional ionospheric corrections for faster PPP convergence. Navig J Inst Navig 61(2):115–124. https://doi.org/10.1002/navi.57

Bennitt GV, Jupp A (2012) Operational assimilation of GPS zenith total delay observations into the met office numerical weather prediction models. Mon Weather Rev 140(8):2706–2719. https://doi.org/10.1175/MWR-D-11-00156.1

Bevis M, Businger S, Herring T, Rocken C, Ware RH (1992) GPS meteorology: remote sensing of atmospheric water vapor using the global positioning system. J Geophys Res 97(D14):15787–15801. https://doi.org/10.1029/92JD01517

Bianchi CE, Pedro Oscar Mendoza L, Isabel Fernández L, Natali MP, Meza AM, Moirano JF (2016) Multi-year GNSS monitoring of atmospheric IWV over central and South America for climate studies. Ann Geophys 34(7):623–639. https://doi.org/10.5194/angeo-34-623-2016

Chatre E, Verhoef P (2018) Galileo programme status update. In: Proceedings of ION GNSS 2018, Institute of Navigation, Miami, FL, USA, September 24–28, pp 733–767

Chen G, Herring TA (1997) Effects of atmospheric azimuthal asymmetry on the analysis of space geodetic data. J Geophys Res 102:20489–20502. https://doi.org/10.1029/97jb01739

Cucurull L, Vandenberghe F, Barker D (2004) Three-dimensional variational data assimilation of ground-based GPS ZTD and meteorological observations during the 14 December 2001 storm event over the Western Mediterranean Sea. Mon Weather Rev 132:749–763. https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0493(2004)1322.0.CO;2

Dach R, Lutz S, Walser P, Fridez P (2015) Bernese GNSS software version 5.2. User manual, Astronomical Institute, University of Bern, Bern Open Publishing. https://doi.org/10.7892/boris.72297. ISBN: 978-3-906813-05-9

De Haan S (2013) Assimilation of GNSS ZTD and radar radial velocity for the benefit of very-short-range regional weather forecasts. Q J R Meteorol Soc 139(667):2097–2107. https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.2087

Ding W, Teferle FN, Kazmierski K, Laurichesse D, Yuan Y (2017) An evaluation of real-time troposphere estimation based on GNSS precise point positioning. J Geophys Res 122(5):2779–2790. https://doi.org/10.1002/2016JD025727

Douša J, Bennitt GV (2013) Estimation and evaluation of hourly updated global GPS zenith total delays over ten months. GPS Solut 17(4):453–464. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10291-012-0291-7

Douša J, Václavovic P (2014) Real-time zenith tropospheric delays in support of numerical weather prediction applications. Adv Sp Res 53(9):1347–1358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asr.2014.02.021

Douša J, Václavovic P, Zhao L, Kačmařík M (2018) New adaptable all-in-one strategy for estimating advanced tropospheric parameters and using real-time orbits and clocks. Remote Sens 10(2):232. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs10020232

Dymarska N, Rohm W, Sierny J, Kapłon J, Kubik T, Kryza M, Jutarski J, Gierczak J, Kosierb R (2017) An assessment of the quality of near-real time GNSS observations as a potential data source for meteorology. Meteorol Hydrol Water Manage 5(1):3–13. https://doi.org/10.26491/mhwm/65146

E-GVAP (2010) EIG EUMETNET GNSS water vapour programme (E-GVAP-II). product requirements document. Met Office. https://egvap.dmi.dk/support/formats/egvap_prd_v10.pdf. Accessed 15 Jul 2020

Elgered G, Plag HP, Van der Marel H, Barlag S, Nash J (2005) COST action 716: exploitation of ground-based GPS for operational numerical weather prediction and climate applications. Official Publications of the European Communities, Luxembourg

Eueler HJ, Goad CC (1991) On optimal filtering of GPS dual frequency observations without using orbit information. Bull Géodésique 65:130–143. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00806368

Gérard P, Luzum B (2010) IERS conventions (2010). (IERS Technical Note; 36) Frankfurt am Main: Verlag des Bundesamts für Kartographie und Geodäsie, 2010. p 179. ISBN 3-89888-989-6

Guerova G, Jones J, Douša J, Dick G, de Haan S, Pottiaux E, Bock O, Pacione R, Elgered G, Vedel H, Bender M (2016) Review of the state of the art and future prospects of the ground-based GNSS meteorology in Europe. Atmos Meas Tech 9(11):5385–5406. https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-9-5385-2016

Haase J, Ge M, Vedel H, Calais E (2003) Accuracy and variability of GPS tropospheric delay measurements of water vapor in the western Mediterranean. J Appl Meteorol 42(11):1547–1568. https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0450(2003)042<1547:AAVOGT>2.0.CO;2

Hadas T (2015) GNSS-warp software for real-time precise point positioning. Artif Satell 50:59–76. https://doi.org/10.1515/arsa-2015-0005

Hadas T, Kaplon J, Bosy J, Sierny J, Wilgan K (2013) Near-real-time regional troposphere models for the GNSS precise point positioning technique. Meas Sci Technol 24(5):055003. https://doi.org/10.1088/0957-0233/24/5/055003

Hadas T, Kazmierski K, Sośnica K (2019) Performance of Galileo-only dual-frequency absolute positioning using the fully serviceable Galileo constellation. GPS Solut 23(4):108. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10291-019-0900-9

Hadas T, Teferle FN, Kazmierski K et al (2017) Optimum stochastic modeling for GNSS tropospheric delay estimation in real-time. GPS Solut 21(3):1069–1081. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10291-016-0595-0

Jin S, Wang J, Park PH (2005) An improvement of GPS height estimations: Stochastic modeling. Earth Planets Sp 57:253–259. https://doi.org/10.1186/BF03352561

Jones J, Guerova G, Douša J, Dick G, de Haan S, Pottiaux E, Bock O, Pacione R, van Malderen R (2020) Advanced GNSS tropospheric products for monitoring severe weather events and climate. Springer International Publishing, Berlin

Kačmařík M, Douša J, Dick G, Zus F, Brenot H, Möller G, Pottiaux E, Kapłon J, Hordyniec P, Václavovic P, Morel L (2017) Inter-technique validation of tropospheric slant total delays. Atmos Meas Tech 10:2183–2280. https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-10-2183-2017

Kačmařík M, Douša J, Zus F, Václavovic P, Balidakis K, Dick G, Wickert J (2019) Sensitivity of GNSS tropospheric gradients to processing options. Ann Geophys 37:429–446. https://doi.org/10.5194/angeo-37-429-2019

Kazmierski K, Hadas T, Sośnica K (2018a) Weighting of multi-GNSS observations in real-time precise point positioning. Remote Sens 10(1):84. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs10010084

Kazmierski K, Sośnica K, Hadas T (2018b) Quality assessment of multi-GNSS orbits and clocks for real-time precise point positioning. GPS Solut 22(1):11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10291-017-0678-6

King RW, Bock Y (2001) Documentation for the GAMIT GPS software analysis, release 10.05. Mass. Inst. of Technol. Cambridge. Atmospheric, and Planetary Science. University of California at San Diego

Lee SW, Kouba J, Schutz B, Kim DH, Lee YJ (2013) Monitoring precipitable water vapor in real-time using global navigation satellite systems. J Geod 87:923–934. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00190-013-0655-y

Li B, Lou L, Shen Y (2016) GNSS elevation-dependent stochastic modeling and its impacts on the statistic testing. J Surv Eng 142(2):04015012. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)SU.1943-5428.0000156

Li X, Dick G, Ge M, Heise S, Wickert J, Bender M (2014) Real-time GPS sensing of atmospheric water vapor: precise point positioning with orbit, clock, and phase delay corrections. Geophys Res Lett 41(10):3615–3621. https://doi.org/10.1002/2013GL058721

Li X, Dick G, Lu C, Ge M, Nilsson T, Ning T, Wickert J, Schih H (2015) Multi-GNSS meteorology: real-time retrieving of atmospheric water vapor from BeiDou, Galileo, GLONASS, and GPS observations. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens 53(12):6385–6393. https://doi.org/10.1109/TGRS.2015.2438395

Lu C, Chen X, Liu G, Dick G, Wickert J, Juang X, Zheng K, Schuh H (2017) Real-time tropospheric delays retrieved from multi-GNSS observations and IGS real-time product streams. Remote Sens 9(12):1317. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs9121317

Lu C, Li X, Cheng J, Dick G, Ge M, Wickert J, Schuh H (2018) Real-time tropospheric delay retrieval from multi-GNSS PPP ambiguity resolution: validation with final troposphere products and a numerical weather model. Remote Sens 10(3):481. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs10030481

Lu C, Li X, Nilsson T, Ning T, Heinkelmann R, Ge M, Glaser S, Schuh H (2015) Real-time retrieval of precipitable water vapor from GPS and BeiDou observations. J Geod 89:843–856. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00190-015-0818-0

Lu C, Zus F, Ge M, Heinkelmann R, Dick G, Wickert J, Schuh H (2016) Tropospheric delay parameters from numerical weather models for multi-GNSS precise positioning. Atmos Meas Tech 9:5965–5973. https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-9-5965-2016

Luo X, Mayer M, Heck B, Awange JL (2014) A realistic and easy-to-implement weighting model for GPS phase observations. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens 52(10):6110–6118. https://doi.org/10.1109/TGRS.2013.2294946

MacMillan DS (1995) Atmospheric gradients from very long baseline interferometry observations. Geophys Res Lett 22(9):1041–1044

Malys S, Jensen PA (1990) Geodetic Point positioning with GPS carrier beat phase data from the CASA UNO experiment. Geophys Res Lett 17(5):651–654

Masoumi S, McClusky S, Koulali A, Tregoning P (2017) A directional model of tropospheric horizontal gradients in global positioning system and its application for particular weather scenarios. J Geophys Res Atmos 122(8):4401–4425. https://doi.org/10.1002/2016JD026184

Mile M, Benáček P, Rózsa S (2019) The use of GNSS zenith total delays in operational AROME/Hungary 3D-var over a central European domain. Atmos Meas Tech 12:1569–1579. https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-12-1569-2019

Pacione R, Vespe F, Pace B (2009) Near real-time GPS zenith total delay validation at E-GVAP super sites. Boll Geod Sci Affini 1

Pan L, Guo F (2018) Real-time tropospheric delay retrieval with GPS, GLONASS Galileo and BDS data. Sci Rep 8:17067. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-35155-3

Rocken C, Van Hove T, Ware R (1997) Near real-time GPS sensing of atmospheric water vapor. Geophys Res Lett 24:3221–3224. https://doi.org/10.1029/97GL03312

Satirapod C, Anonglekha S, Choi YS, Lee HK (2011) Performance assessment of GPS-sensed precipitable water vapor using IGS ultra-rapid orbits: a preliminary study in Thailand. Eng J 15:1–8. https://doi.org/10.4186/ej.2011.15.1.1

Schönemann E (2014) Analysis of GNSS raw observations in PPP solutions. Dissertation, Technische Universität Darmstadt

Shi J, Xu C, Guo J, Gao Y (2015a) Real-time GPS precise point positioning-based precipitable water vapor estimation for rainfall monitoring and forecasting. IEEE Trans Geosci Remote Sens 53:3452–3459. https://doi.org/10.1109/TGRS.2014.2377041

Shi J, Xu C, Li Y, Gao Y (2015b) Impacts of real-time satellite clock errors on GPS precise point positioning-based troposphere zenith delay estimation. J Geod 89:747–756. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00190-015-0811-7

Steigenberger P, Montenbruck O (2017) Galileo status: orbits, clocks, and positioning. GPS Solut 21(2):319–331

Tralli DM, Lichten SM (1990) Stochastic estimation of tropospheric path delays in global positioning system geodetic measurements. Bull Géodésique 64:127–159. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02520642

Vedel H, De Haan S, Jones J, Bennitt G, Offiler D (2013) E-GVAP third phase. Geophys Res Abstr 15:EGU2013–10919

Yan X, Ducrocq V, Poli P, Hakam M, Jaubert G, Walpersdorf A (2009) Impact of GPS zenith delay assimilation on convective-scale prediction of Mediterranean heavy rainfall. J Geophys Res Atmos. https://doi.org/10.1029/2008JD011036

Yuan Y, Zhang K, Rohm W, Choy S, Norman R, Wang CS (2014) Real-time retrieval of precipitable water vapor from GPS precise point positioning. J Geophys Res Atmos 119(16):10044–10057. https://doi.org/10.1002/2014jd021486

Yuan Y, Holden L, Kealy A, Choy S, Hordyniec P (2019) Assessment of forecast Vienna mapping function 1 for real-time tropospheric delay modeling in GNSS. J Geodesy 93:1501–1514. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00190-018-1203-6

Zhao Q, Yao Y, Yao W, Li Z (2018) Real-time precise point positioning-based zenith tropospheric delay for precipitation forecasting. Sci Rep 8:7939. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-26299-3

Zumberge JF, Heflin MB, Jefferson DC, Watking MM, Webb FH (1997) Precise point positioning for the efficient and robust analysis of GPS data from large networks. J Geophys Res Solid Earth 102(B3):5005–5017. https://doi.org/10.1029/96JB03860

Acknowledgements

Open Access funding provided by Projekt DEAL. This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Grant Agreement No. 835997. We acknowledge CNES for providing multi-GNSS real-time orbit and clock products, IGS (USNO) for providing ZTD final products, NOAA/NCEP for providing GFS atmospheric model. We thank Ela Lasota for her technical assistance and help in preparing GFS model datasets.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hadas, T., Hobiger, T. & Hordyniec, P. Considering different recent advancements in GNSS on real-time zenith troposphere estimates. GPS Solut 24, 99 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10291-020-01014-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10291-020-01014-w