Abstract

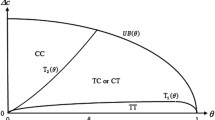

This study proposes a model of learning by supplying in an international outsourcing framework, where the supplier of a relationship-specific input can reverse engineer and become a competitor to its partner in the final goods market. Transmitting knowledge to a more capable supplier therefore creates competitive threat despite the benefits it brings within an outsourcing relationship. In particular, in markets with less differentiated products and for standard inputs that require less knowledge to be shared, choosing an intermediate capability level supplier prompts a strategic expansion of output to deter supplier entry in the final goods market, resulting in higher profits and welfare. A highly capable supplier is instead accommodated as a rival and is a source of royalty income when the relationship-specific input embeds more knowledge about the final product and when the competing varieties are differentiated.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Samsung developed its capability by undertaking GE’s production. Please refer to pp. 136–140 of Kim (1997), and pp. 202–206 of Cyhn (2002). The Korean automobile industry instead began from basic assembly and input production for foreign automobile companies. Please refer to Kim (1997), pp. 105–130, for details.

Chu (2009) provides a detailed illustration of the transition from OEM to OBM in East Asia, and finds that the Chinese and Korean firms tend to be more active in following this path than Taiwanese firms.

Boeing Japan’s report “Made with Japan: A Partnership on the Frontiers of Aerospace,”, page 6. Available online at: http://www.boeing.jp/resources/ja_JP/Boeing-in-Japan/Made-with-Japan/1122_boeing_cb13_final.pdf. According to the report, Mitsubishi also designs and produces the wings of the 787. Furthermore, this is the first time that Boeing has entrusted such a critical component to an outside supplier.

For an overview of the literature on IP rights as an alternative determinant of reverse-engineering costs, see among others Chin and Grossman (1990), Deardorff (1992), Helpman (2003), Vishwasrao (1994), Zigic (1998, 2000), Saggi (1999), Yang and Maskus (2001), Markusen (2001), Glass and Saggi (2002), Glass (2004), Grossman and Lai (2004), Mukherjee and Pennings (2004), Naghavi (2007), Leahy and Naghavi (2010), Mukherjee (2017), Ghosh et al. (2018), and Ghosh and Ishikawa (2018).

This assumption is justified by interpreting \(w_{j}\) as the productivity of labor in producing \(q_{0}\) in region j. In other words, we assume that, in the North, a unit of labor is capable of producing \(\theta _{N}\) units of \(q_{0}\), while in the South, a unit of labor can only produce \(\theta _{S}\) units of \(q_{0}\), where \(\theta _{N}>\theta _{S}\). Since the price for each unit of \(q_{0}\) is 1 and the homogeneous sector is perfectly competitive, it must be that the wage of each unit of labor is equal to its marginal productivity. In other words, \(p_{0}\theta _{N}=\theta _{N}=MPL_{N}=w_{N}\) and \(p_{0}\theta _{S}=\theta _{S}=MPL_{S}=w_{S}\). We can further normalize Southern productivity such that \(\theta _{N}>\theta _{S}=1\) and, hence, \(w_{N}>w_{S}=p_{0}=1\).

Note that supplier capability does not only apply to their effort within the relationship, but also to their learning and innovation capacity that determines their individual benefits. Firms can therefore obtain this information by observing supplier-specific characteristics, such as its history of patents.

We focus only on the interesting case where \(e<{\overline{e}}\).

Let \({\overline{e}}\equiv \frac{\sqrt{33}}{3}-1\approx 0.915\). \(\zeta ^{D}\) tends to infinity when \(e\rightarrow {\overline{e}}\) (Please refer to Online Appendix A.3). For \(\zeta \ge \zeta ^{P}\), when e is larger than \(\overline{e }\), the effect of e on \(q_{N}^{P}\left( e,\zeta \right)\) always dominates the effect of \(\zeta\), causing \(q_{N}^{P}\left( e,\zeta \right)\) to be very small. As a result, N would never prefer the Stackelberg scheme in this case and strategic predation always prevails.

This is reminiscent of Defever and Toubal (2013) who show profits from outsourcing to rise with firm productivity, with the effect magnified for contract intensive inputs, a proxy obtained by measuring input relation-specificity (Nunn 2007). In a parallel manner, pairing with a more capable supplier in our framework increases profits, but more so when sourcing more knowledge intensive inputs.

We can easily show that \(\frac{CS^{P}\left( \zeta ^{D}\right) }{CS^{D}}=\frac{ 4\left( 4-4e^{2}+e\left( 4-3e^{2}\right) +2e\sqrt{e\left( 1-e\right) \left( 4-3e^{2}\right) }\right) ^{2}}{e^{2} \left( 128-32e-156e^{2}+36e^{3}+33e^{4}\right) }>1\) holds throughout \(e\in \left[ 0,{\overline{e}}\right)\).

To see this, in Online Appendix A.7 and A.9 we show that the Stackelberg limit profit and total surplus are independent of \(\gamma\), while the maximum profit and total surplus with strategic predation are always increasing in \(\gamma\), and outperform those under Stackelberg if e is sufficiently large.

Note that learning by supplying in this case raises the consumer surplus but reduces the producer surplus. To see that the consumer surplus increases in this case, recall that the consumer surplus equals \(\frac{1}{2} \left( a-p_{N}\right) q_{N}\) for \(\zeta <\zeta ^{D}\). Because \(q_{N}^{P}\left( e,\zeta \right) >q_{N}^{M}\) and hence \(p\left( q_{N}^{M} \right) >p\left( q_{N}^{P}\left( e,\zeta \right) \right)\), it follows that \(CS^{D}\ge CS_{no}\). To see that the producer surplus decreases for \(\zeta \in \left[ \zeta ^{M},\zeta ^{D}\right)\), note that \(q_{N}^{P}>q_{N}^{M}\) implies that \(R^{M}\left( q_{N}\right) \ge R^{M}\left( q_{N}^{P}\right)\). Since \(PS^{no}\) equals to the profit under natural monopoly, it follows that \(PS^{no}\ge \Pi _{N}^{*}\).

To see that the consumer surplus increases, note that direct comparison between \(CS^{D}\) and \(CS^{no}\) shows that \(CS^{D}\ge CS^{no}\) if and only if \(-3e^{4}+36e^{3}-60e^{2}-32e+64\ge 0\). It is readily checked that this condition holds for \(e\in \left( 0,1\right)\). To see the possibility that the producer surplus can decrease, note that \(PS^{no}\) equals to the profit under natural monopoly, and is greater than \(\Pi _{N}\left( q_{N}^{P}\left( e, \zeta \right) \right)\) for all \(\zeta\). Recall from Proposition 3 that at \(\zeta ^{D}\), \(\Pi _{N}^{*}\) jumps downwards from \(\Pi _{N}\left( q_{N}^{P}\left( e,\zeta ^{D}\right) \right)\) to \(\Pi _{N}\left( q_{N}^{D},\zeta ^{D}\right)\), we conclude that \(PS^{no}\ge \Pi _{N}\left( q_{N}^{D},\zeta \right)\) holds for some range of \(\zeta >\zeta ^{D}\).

This is done by simply comparing \(\pi _{NH}\) with the maximum profit in each market structure when outsourcing emerges, i.e., \(\Pi \left( \zeta ^{P}\right)\) for natural monopoly, (26) for strategic predation, and (27) for Stackelberg.

We can rewrite equation (21) as \(2\Pi _{N}^{*}\ge \frac{m^{2}}{4}-w_{S}f_{M}\). Observe that its left-hand side depends on \(\zeta\), while its right-hand side is a constant independent of \(\zeta\). Therefore, the condition for outsourcing to emerge is derived by replacing \(\Pi _{N}^{*}\) on the left-hand side of (21) with the maximum profit in each market structure, i.e., \(\Pi \left( \zeta ^{P} \right)\) for natural monopoly, (26) for strategic predation, and (27) for Stackelberg.

References

Acemoglu, D., Antras, P., & Helpman, E. (2007). Contracts and technology adoption. American Economic Review, 97, 916–943.

Alcacer, J., & Oxley, J. (2014). Learning by supplying. Strategic Management Journal, 35, 204–223.

Antràs, P. (2003). Firms, contracts, and trade structure. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(4), 1375–1418.

Antràs, P. (2005). Incomplete contracts and the product cycle. American Economic Review, 95, 1054–1073.

Antràs, P. (2014). Grossman-Hart (1986) Goes global: Incomplete contracts, property rights, and the international organization of production. Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, 30, 118–175.

Arnold, J. M., & Javorcik, B. (2009). Gifted kids or pushy parents? Foreign direct investment and plant productivity in Indonesia. Journal of International Economics, 79(1), 42–53.

Antràs, P., & Chor, C. (2013). Organizing the global value chain. Econometrica, 81, 2127–2204.

Antràs, P., & Helpman, E. (2004). Global sourcing. Journal of Political Economy, 112, 552–580.

Becker, G. (1964). Human capital. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Blalock, G., & Gertler, P. J. (2008). Welfare Gains from foreign direct investment through technology transfer to local suppliers. Journal of International Economics, 74(2), 402–421.

Chen, Y., Dubey, P., & Sen, D. (2011). Outsourcing induced by strategic competition. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 29, 484–492.

Chen, Y., Ishikawa, J., & Yu, Z. (2004). Trade liberalization and strategic outsourcing. Journal of International Economics, 63, 419–436.

Chin, J., & Grossman, G. (1990). Intellectual property rights and North–South trade. In R. Jones & A. O. Krueger (Eds.), The political economy of international trade. Cambridge: Basil Blackwell.

Chu, W. W. (2009). Can Taiwan’s second movers upgrade via branding? Research Policy, 38, 1054–1065.

Crespo, N., & Fontoura, M. P. (2007). Determinant factors of FDI spillovers ? What do we really know? World Development, 35(3), 410–425.

Cyhn, J. W. (2002). Technology transfer and international production: the development of the electronics industry in Korea. Cheltenham: Elgar.

Deardorff, A. V. (1992). Welfare effects of global patent protection. Economica, 59, 35–51.

Defever, F., & Toubal, F. (2013). Productivity, relationship-specific inputs and the sourcing modes of multinationals. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 94, 345–357.

Ghosh, A., & Ishikawa, J. (2018). Trade liberalization, absorptive capacity and the protection of intellectual property rights. Review of International Economics, 26, 997–1020.

Ghosh, A., Kato, T., & Morita, H. (2017). Incremental innovation and competitive pressure in the presence of discrete innovation. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 135, 1–14.

Ghosh, A., Morita, H., & Nguyen, X. (2018). Technology spillovers, intellectual property rights, and export-platform FDI. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 151, 171–190.

Glass, A. J., & Saggi, K. (2002). Intellectual property rights and foreign direct investment. Journal of International Economics, 56, 387–410.

Glass, A. J. (2004). Outsourcing under imperfect protection of intellectual property. Review of International Economics, 12, 867–884.

Gilbert, R., & Kristiansen, E. G. (2018). Licensing and innovation with imperfect contract enforcement. Journal of Economics and Management Strategy, 27, 297–314.

Görg, H., & Greenaway, D. (2004). Much ado about nothing? Do domestic firms really benefit from foreign direct investment? World Bank Research Observer, 19(2), 171–197.

Goswami, A. (2013). Vertical FDI versus outsourcing: the role of technology transfer costs. North American Journal of Economics and Finance, 25, 1–21.

Green, J. R., & Scotchmer, S. (1995). On the division of profit in sequential innovation. RAND Journal of Economics, 26, 20–33.

Grossman, G., & Helpman, E. (2002). Integration vs. outsourcing in industry equilibrium. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117, 85–120.

Grossman, G., & Helpman, E. (2003). Outsourcing versus FDI in industry equilibrium. Journal of the European Economic Association, 1, 317–327.

Grossman, G., & Helpman, E. (2005). Outsourcing in global economy. Review of Economic Studies, 72, 135–159.

Grossman, G., & Lai, E. L.-C. (2004). International protection of intellectual property. American Economic Review, 94, 1635–1653.

Guadalupe, M., Kuzmina, O., & Thomas, C. (2012). Innovation and foreign ownership. American Economic Review, 102(7), 3594–3627.

Haskel, J. E., Pereira, S. C., & Slaughter, M. J. (2007). Does inward foreign direct investment boost the productivity of domestic firms? Review of Economics and Statistics, 89(3), 482–496.

Helpman, E. (2003). Innovation, imitation, and intellectual property rights. Econometrica, 61, 1247–1280.

Helpman, E. (2006). Trade, FDI, and the organization of firms. Journal of Economic Literature, 44, 589–639.

Hobday, M. (2000). East versus Southeast Asian innovation systems: comparing OEM- and TNC- led growth in electronics. In L. Kim & R. R. Nelson (Eds.), Technology, learning and innovation: experiences of newly industrializing economies (pp. 129–169). Cambridge: Harvard Business School Press.

Javorcik, B. (2004). Does foreign direct investment increase the productivity of domestic firms? In search of spillovers through backward linkages. American Economic Review, 94(3), 605–627.

Kim, L. (1997). Imitation to innovation: The dynamics of Korea’s technological learning. Cambridge: Harvard Business School Press.

Kugler, M. (2006). Spillovers from foreign direct investment: Within or between industries? Journal of Development Economics, 80(2), 444–477.

Leahy, D., & Naghavi, A. (2010). Intellectual property rights and entry into a foreign market: FDI vs. joint ventures. Review of International Economics, 18, 633–649.

Liu, Z. (2008). Foreign direct investment and technology spillovers: Theory and evidence. Journal of Development Economics, 85(1–2), 176–193.

Markusen, J. (2001). Contracts, intellectual property rights, and multinational investment in developing countries. Journal of International Economics, 53, 189–204.

Mukherjee, A., & Pennings, E. (2004). Imitation, patent protection and welfare. Oxford Economic Papers, 56, 715–733.

Mukherjee, A., & Tsai, Y. (2013). Multi-sourcing as an entry deterrence strategy. International Review of Economics and Finance, 25, 108–112.

Mukherjee, A. (2017). Patent protection and R&D with endogenous market structure. Journal of Industrial Economics, 65, 220–234.

Naghavi, A. (2007). Strategic intellectual property right policy and North–South technology transfer. Review of World Economics, 143, 55–78.

Naghavi, A., & Ottaviano, G. (2009). Offshoring and product innovation. Economic Theory, 38, 517–532.

Naghavi, A., Peng, S. K., & Tsai, Y. (2017). Outsourcing, relationship-specific investments, and supplier heterogeneity. Review of International Economics, 25, 626–648.

Neary, J. P., & Tharakan, J. (2012). International trade with endogenous mode of competition in general equilibrium. Journal of International Economics, 86, 118–132.

Nunn, N. (2007). Relationship-specificity, incomplete contracts and the pattern of trade. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 122(2), 569–600.

Pack, H., & Saggi, K. (2001). Vertical technology transfer via international outsourcing. Journal of Development Economics, 65, 389–415.

Rodríguez-Clare, A. (1996). Multinationals, linkages, and economic development. American Economic Review, 86(4), 852–873.

Saggi, K. (1999). Foreign direct investment, licensing, and incentives for innovation. Review of International Economics, 7, 699–714.

Schwarz, C., & Suedekum, J. (2014). Global sourcing of complex production processes. Journal of International Economics, 93, 123–139.

Singh, N., & Vives, X. (1984). Price and quantity competition in a differentiated duopoly. Rand Journal of Economics, 15, 546–554.

Van Biesebroeck, J., & Zhang, L. (2014). Interdependent product cycles for globally sourced intermediates. Journal of International Economics, 94, 143–156.

Vishwasrao, S. (1994). Intellectual property rights and the mode of technology transfer. Journal of Development Economics, 44, 381–402.

Wang, J.-W., & Blomström, M. (1992). Foreign investment and technology transfer: A simple model. European Economic Review, 36(1), 137–155.

Yang, G., & Maskus, K. E. (2001). Intellectual property rights, licensing, and innovation in an endogenous product-cycle model. Journal of International Economics, 53, 169–187.

Yu, H. H., & Shih, W. C. (2014). Taiwan’s PC Industry, 1976–2010: The evolution of organizational capabilities. Business History Review, 88, 329–357.

Zigic, K. (1998). Intellectual property rights violations and spillovers in North–South trade. European Economic Review, 42, 1779–1799.

Zigic, K. (2000). Strategic trade policy, intellectual property rights protection, and North–South trade. Journal of Development Economics, 61, 27–60.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Tse-Chien Hsu, Wen-Tai Hsu, Ching-I Huang, Bih-Jane Liu, Yasuhiro Sato, Takatoshi Tabuchi, Jacques Thisse, Tsung-Sheng Tsai, Cheng-Chen Yang, and the participants of 2016 Osaka Conference on Spatial and Urban Economics for very helpful comments. Financial support from the Academia Sinica IA-105-H04 is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, YF., Naghavi, A. & Peng, SK. Learning by supplying and competition threat. Rev World Econ 157, 121–148 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-020-00386-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-020-00386-y

Keywords

- International outsourcing

- Supplier heterogeneity

- Competitive threat

- Reverse engineering

- Strategic predation

- Technological capability

- Learning by supplying

- Royalty payment

- Knowledge intensity