Abstract

Contrary to widespread presumption, a surprisingly large number of countries have been able to finance a significant fraction of their investment for extended periods using foreign finance. While many of these episodes are in countries where official finance is important, we also identify episodes where a substantial fraction of domestic investment is financed by private capital inflows. Although there is evidence of a positive growth effect of such inflows in the short run, that positive impact dissipates after 5 years and turns negative over longer horizons. Many such episodes end abruptly, with compression of the current account and sharp slowdowns in investment and growth. Summing over the inflow (current account deficit) episode and its aftermath, we find that growth is slower than when countries rely on domestic savings. The implication is that financing growth and investment out of foreign savings, while not impossible, is risky and too often counterproductive.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Although the difference in long-run growth between episodes and non-episodes is not always statistically significant.

Reinhart and Trebesch (2015) suggest that Greece’s long history of debt crisis is a classic example of the pitfalls of relying on external financing.

Adalet and Eichengreen (2007) document that current account reversals were relatively few before 1914, compared to the last quarter of the 20th century. This speaks to the third related literature considered in the next paragraph.

We use total net official flows and divide them by the current account balance. We set this variable equal to zero for country-years with negative official flows or a current account surplus.

These values are 1.2% of GDP when we look at 4% current account deficits, 1.6% of GDP for 6% current account deficits, 2.4% of GDP for 8% current account deficits, and 3% of GDP for 10% current account deficits.

Table O1 in the online appendix considers 6, 8 and 10% episodes.

In contrast, large and persistent current account deficits are associated with above-average FDI inflows. While portfolio inflows are also higher than in than control group cases, the difference is not large, and it is never statistically significant for developing countries. Whether large current account deficits financed mainly by FDI “turn out better”—whether or not followed by equally sharp changes in GDP growth—is a separate question, to which we turn in Sects. 4 and 5 below.

This is in line with the results of Table 2 showing that episodes are more frequent in developing countries.

It goes up to 3 percentage points in the 8% episodes, though the difference is not always statistically significant.

While there is much analysis of why some countries earn excess returns on their net foreign assets and whether these returns are sustainable (see inter alia Gourinchas and Rey 2007; Curcuru et al. 2007; Hausmann and Sturzenegger 2007; Eichengreen 2004), we simply note that countries may be able to run larger current account deficits when the return on their gross foreign assets is higher than that on their gross foreign liabilities.

There are instead no clear patterns for GDP growth. The real exchange rate tends to depreciate at the end of the episode but the effect is not statistically significant.

Balance of payments accounting distinguishes three main sources of external financing: (i) capital transfers (for example, grants and debt forgiveness by creditors) which are recorded in the capital account of the balance of payment; (ii) liabilities creating capital inflows (direct investment, portfolio investment, other investment, and changes in reserve assets) which are recorded in the financial account of the balance of payments; and (iii) net errors and omissions which is a residual category to insure that the balance of payments sums to zero.

The results of columns 7 and 8 and difficult to interpret because, when we consider 10% episodes, the dependent variable becomes collinear with the advanced economies and Asian dummies.

Tables O2 and O3 in the online appendix report results for 6, 8, and 10% episodes.

Results are essentially identical if we estimate this model without controlling for the saving rate.

We define as high FDI inflows periods where FDI inflows relative to GDP are above the sample median.

Since we have four models and four thresholds, we estimate a total of 320 regressions. Full regression results are in Tables O7–O22 in the online Appendix.

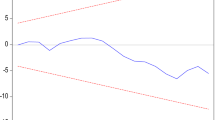

For instance, the top left panel of Fig. 3 plots the coefficients of the regressions reported in Table O7: when h = 1, EPI has a positive and statistically significant coefficient (the point estimate is 0.0205), the coefficient remains positive and statistically significant until h = 4, at h = 5 is positive but not significant, and at h = 6 it becomes negative but still insignificant. For h > 6, the coefficient remains negative but it is never statistically significant. The top-left panel of Fig. 7, instead, plots the coefficient reported in Table A12. In this case, the coefficient is always positive but not statistically significant when h > 6.

A possible solution to this problem would be estimating a full-fledged simultaneous equation model, but the estimation of such a model is well beyond the objective of this paper.

For 8 and 10% episodes, there seem to be no difference between episodes with large and small FDI flows.

We would like to thank an anonymous referee for suggesting to drop low income countries and intermediate cases.

The first stages of the IH regressions pass the standard weak instrument and specification tests. The Cragg Donald Wald F test is 14.87 for the regressions that focus on 4% episodes, 19.69 for 6% episodes, 20.39 for 8% episodes, and 13.95 for 10% episodes. The p value of the Sargan tests are 0.36, 0.71, 0.74, and 0.92, respectively.

That difference is statistically significant at year 11.

References

Adalet, M., & Eichengreen, B. (2007). Current account reversals: always a problem? In G7 current account imbalances: Sustainability and adjustment, Clarida. 2007.

Apergis, N., & Tsouimas, C. (2009). A survey of the Feldstein-Horioka puzzle: What has been done and where we stand. Research in Economics, 63, 64–76.

Bayoumi, T. (1990). Savings-investment correlations: Immobile capital, government policy or endogenous behavior? IMF Staff Papers, 37, 360–387.

Benigno, G., & Fornaro, L. (2014). The financial resource curse. Scandinavian Journal of Ecnoomics, 116, 58–86.

Blanchard, O. (2007). Adjustment within the Euro: The difficult case of Portugal. Portuguese Economic Journal, 6, 1–21.

Bussière, M., & Fratzscher, M. (2008). Financial openness and growth: Short-run gain, long-run pain? Review of International Economics, 16(1), 69–95.

Calvo, G., Izquierdo, A., & Mejía, L.-F. (2004). On the empirics of sudden stops: The relevance of balance-sheet effects. Paper presented at the conference “Emerging Markets and Macroeconomic Volatility: Lessons from a Decade of Financial Debacles,” San Francisco, United States, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, June 4–5.

Carlson, M., & Hernandez, L. (2002). Determinants and repercussions of the composition of capital inflows (International Finance Discussion Paper 717). Washington, DC, United States: United States Federal Reserve System.

Catão, L. A., & Milesi-Ferretti, G. M. (2014). External Liabilities and Crises. Journal of International Economics, 94, 18–32.

Cavallo, E., & Frankel, J. (2008). Does openness to trade make countries more vulnerable to external crises, or less? Using gravity to establish causality. Journal of International Money and Finance, 27, 1430–1452.

Cavallo, E., Powell, A., Pedemonte, M., & Tavella, P. (2015). A new taxonomy of sudden stops: Which sudden stops should countries be most concerned about? Journal of International Money and Finance, 51, 47–70.

Curcuru, S., Dvorak, T., & Warnock, F. (2007). The stability of large external imbalances: The role of returns differentials (NBER Working Paper 13074). Cambridge, United States: National Bureau of Economic Research.

De Long, J. B., & Summers, L. H. (1991). Equipment investment and economic growth. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 106(2), 445–502.

Edwards, S. (2004). Financial openness, sudden stops, and current-account reversals. American Economic Review, 94, 59–64.

Eichengreen, B. (1985). The Gold Standard since Alec Ford. In B. Eichengreen & M. Flandreau (Eds.), The Gold standard in theory and history (pp. 187–206). London: Routledge.

Eichengreen, B. (2004). Global imbalances and the lessons of Bretton Woods (NBER Working Paper 10497). Cambridge, United States: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Eichengreen, B., & Panizza, U. (2016). A surplus of ambition: Can Europe rely on large primary surpluses to solve its debt problem? Economic Policy, 31(85), 5–49.

Feldstein, M., & Horioka, C. (1980). Domestic saving and international capital flows. Economic Journal, 90(358), 314–329.

Fischer, Stanley. (1988). Real balances, the exchange rate, and indexation: Real variables in disinflation. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 103(1), 27–49.

Fischer, S. (1994). Comments on Dornbusch and Werner. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, No. 1, pp. 304–309.

Fischer, Stanley. (2003). Financial crises and reform of the international financial system. Review of World Economics/Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, 139(1), 1–37.

Fishlow, A. (1985). Lessons from the past: Capital markets during the 19th century and the interwar period. International Organization, 39, 383–439.

Frankel, J. A., & Rose, A. K. (1996). Currency crashes in emerging markets: An empirical treatment. Journal of International Economics, 41, 351–366.

Freund, C., & Warnock, F. (2007). Current account deficits in industrial countries: The bigger they are, the harder they fall? In G7 current account imbalances: Sustainability and adjustment, Clarida, 2007.

Ghosh, A., & Ramakrishnan, U. (2017). Current account deficits? Is there a Problem? Finance and Development. http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/basics/current.htm.

Gopinath, G., Kalemli-Ozcan, S., Karabarbounis, L., & Villegas-Sanchez, C. (2016). Capital allocation and productivity in South Europe. Quarterly Journal of Economics (forthcoming).

Gourinchas, P-O., & Rey, H. (2007). From world banker to world venture capitalist: U.S. external adjustment and the exorbitant privilege. In R. Clarida (Ed.), G7 current account imbalances: Sustainability and adjustment, Chicago, United States.

Gourinchas, P.-O., Valdes, R., & Landerretche, O. (2001, January). Lending Booms: Latin America and the World. Economic Journal of the Latin American and Caribbean Economic Association.

Hausmann, R., & Sturzenegger, F. (2007). The missing dark matter in the wealth of nations and its implications for global imbalances. Economic Policy, 22, 469–518.

Hogan, V. P., & Rigobón, R. (2003). Using heteroscedasticity to estimate the returns to education (Working Papers 200301). Dublin, Ireland: University College Dublin, School of Economics.

Jordà, Ò. (2005). Estimation and inference of impulse responses by local projections. American Economic Review, 95, 161–182.

Jordà, Ò., Schularick, M., & Taylor, A. (2011). Financial crises, credit booms and external imbalances: 140 Years of lessons. IMF Economic Review, 59, 340–378.

Laeven, L., & Valencia, F. (2012). Systemic banking crises database: An update (IMF Working Paper 12/163). Washington, DC, United States: International Monetary Fund.

Lewbel, A. (2012). Using heteroscedasticity to identify and estimate mismeasured and endogenous regressor models. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics, 30(1), 67–80.

Milesi Ferretti, G. M., & Razin, A. (2000). Current account reversals and currency crises: Empirical regularities. In Currency Crises, Krugman, 2000.

Prasad, E., Rajan, R., & Subramanian, A. (2007). Foreign capital and economic growth. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Economic Studies Program, The Brookings Institution, vol. 38(2007-1), pp. 153–230.

Ranciere, R., Tornell, A., & Westermann, F. (2006). Decomposing the effects of financial liberalization: Crises vs. growth. Journal of Banking & Finance, 30, 3331–3348.

Reinhart, C., & Trebesch, C. (2015). The pitfalls of external dependence: Greece, 1829–2015. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity (Fall), 307–328.

Reisen, H. (1997). The limits of foreign savings. In R. Hausmann & H. Reisen (Eds.), Promoting savings in Latin America (pp. 233–264). Washington/Paris: IDB/OECD.

Schularick, M., & Steger, T. (2010). Financial integration, investment and economic growth: Evidence from two eras of financial globalization. Review of Economics and Statistics, 92, 756–758.

Taylor, A. (1994). Domestic saving and international capital flows reconsidered (NBER Working Paper 4892). Cambridge, United States: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Taylor, A. (2013). External imbalances and financial crises (IMF Working Paper no. WP/13/260).

Tornell, A., & Westermann, F. (2002). Boom-bust cycles in middle income countries: Facts and explanation. IMF Staff Papers, Palgrave Macmillan, vol. 49(Special i), pp. 111–155.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Luis Servén, and two anonymous referees for very useful comments and Kailin Chen, Matías Marzani and Juan Espinosa for research assistance. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Inter-American Development Bank, its Board of Directors, or the countries they represent.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

About this article

Cite this article

Cavallo, E., Eichengreen, B. & Panizza, U. Can countries rely on foreign saving for investment and economic development?. Rev World Econ 154, 277–306 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-017-0301-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-017-0301-5