Abstract

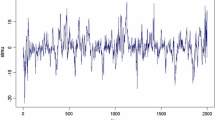

Structural change in any time series is practically unavoidable, and thus correctly detecting breakpoints plays a pivotal role in statistical modelling. This research considers segmented autoregressive models with exogenous variables and asymmetric GARCH errors, GJR-GARCH and exponential-GARCH specifications, which utilize the leverage phenomenon to demonstrate asymmetry in response to positive and negative shocks. The proposed models incorporate skew Student-t distribution and prove the advantages of the fat-tailed skew Student-t distribution versus other distributions when structural changes appear in financial time series. We employ Bayesian Markov Chain Monte Carlo methods in order to make inferences about the locations of structural change points and model parameters and utilize deviance information criterion to determine the optimal number of breakpoints via a sequential approach. Our models can accurately detect the number and locations of structural change points in simulation studies. For real data analysis, we examine the impacts of daily gold returns and VIX on S&P 500 returns during 2007–2019. The proposed methods are able to integrate structural changes through the model parameters and to capture the variability of a financial market more efficiently.

Similar content being viewed by others

Change history

05 December 2020

The layout of several tables was corrupted in the original publication. The table layout has been corrected.

References

Alberg D, Shalit H, Yosef R (2008) Estimating stock market volatility using asymmetric GARCH models. Appl Financ Econ 18:1201–1208

Bai J, Perron P (2003) Computation and analysis of multiple structural change models. J Appl Econ 18:1–22

Bollerslev T (1986) Generalized autoregressive conditional heteroskedasticity. J Econom 31:307–327

Bradley BO, Taqqu MS (2003) Financial risk and heavy tails. In: Handbook of heavy tailed distributions in finance, North-Holland, pp 35–103

Chen CWS, Chiang TC, So MKP (2003) Asymmetrical reaction to US stock-return news: evidence from major stock markets based on a double-threshold model. J Econ Bus 55:487–502

Chen CWS, Gerlach R, Liu FC (2011) Detection of structural breaks in a time-varying heteroscedastic regression model. J Stat Plan Inference 141:3367–3381

Chen CWS, So MKP (2006) On a threshold heteroscedastic model. Int J Forecast 22:73–89

Chiang TC, Chen CWS, So MKP (2007) Asymmetric return and volatility responses to composite news from stock markets. Multinatl Financ J 11:179–210

Chib S (1998) Estimation and comparison of multiple changepoint models. J Econom 86:221–242

Davis RA, Lee TC, Rodriguez-Yam GA (2006) Structural break estimation for nonstationary time series models. J Am Stat Assoc 101:223–239

Dong MC, Chen CWS, Lee S, Sriboonchitta S (2019) How strong is the relationship among gold and USD exchange rates? Analytics based on structural change models. Comput Econ 53:343–366

Engle RF (1982) Autoregressive conditional heteroscedasticity with estimates of the variance of United Kingdom inflation. Econometrica 50:987–1008

Fearnhead P, Liu Z (2005) On-line inference for multiple changepoints problems. J R Stat Soc Ser B Stat Methodol 69:589–605

Gelman A, Roberts GO, Gilks WR (1996) Efficient metropolis jumping rules. In: Bernardo JM, Berger JO, Dawid AP, Smith AFM (eds) Bayesian statistics, vol 5. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 599–608

Giordani P, Kohn R (2012) Efficient Bayesian inference for multiple change-point and mixture innovation models. J Bus Econ Stat 196:66–77

Giot P (2005) Relationships between implied volatility indices and stock index returns. J Portf Manag 31:92–100

Glosten LR, Jagannathan R, Runkle DE (1993) On the relation between the expected value and the volatility of the nominal excess return on stocks. J Financ 487:1779–1801

Hansen BE (1994) Autoregressive conditional density estimation. Int Econ Rev 35:705–730

Hastings WK (1970) Monte Carlo sampling methods using Markov chains and their applications. Biometrika 57:97–109

Inclán C (1993) Detection of multiple changes of variance using posterior odds. J Bus Econ Stat 11:289–300

Inclán C, Tiao GC (1994) Use of cumulative sums of squares for retrospective detection of changes of variance. J Am Stat Assoc 89:913–923

Kim CJ, Nelson CR, Piger J (2004) The less-volatile US economy: a Bayesian investigation of timing, breadth, and potential explanations. J Bus Econ Stat 22:80–93

Lai TL, Xing H (2013) Stochastic change-point ARX-GARCH models and their applications to econometric time series. Stat Sin 23:1573–1594

Mandelbrot BB (1963) The variation of certain speculative prices. J Bus 36:392–417

Metropolis N, Rosenbluth AW, Rosenbluth MN, Teller AH, Teller E (1953) Equation of state calculations by fast computing machines. J Chem Phys 21:1087–1092

Nelson DB (1991) Conditional heteroscedasticity in asset pricing: a new approach. Econometrica 59:347–370

Pesaran MH, Pettenuzzo D, Timmermann A (2006) Forecasting time series subject to multiple structural breaks. Rev Econ Stud 73:1057–1084

Pesaran MH, Timmermann A (2004) How costly is it to ignore breaks when forecasting the direction of a time series? Int J Forecast 20:411–425

Poon SH, Granger CWJ (2003) Forecasting volatility in financial markets: a review. J Econ Lit 41:478–539

Ray BK, Tsay RS (2002) Bayesian methods for change-point detection in long-range dependent processes. J Time Ser Anal 23:687–705

Spiegelhalter DJ, Best NG, Carlin BP, Van der Linde A (2002) Bayesian measures of model complexity and fit (with discussion). J R Stat Soc Ser B Stat Methodol 64:83–616

Stock J, Watson M (1996) Evidence on structural instability in macroeconomic time series relations. J Bus Econ Stat 14:11–30

Than-Thi H, Dong MC, Chen CWS (2019) Bayesian modelling structural changes on housing price dynamics. In: Kreinovich V, Sriboonchitta S (eds) Structural changes and their econometric modeling. Studies in computational intelligence, vol 808. Springer, Cham, pp 83–104

Tsay RS (2013) An introduction to analysis of financial data with R. Wiley, Hoboken

Zeileis A, Kleiber C, Krämer W, Hornik K (2003) Testing and dating of structural changes in practice. Comput Stat Data Anal 44:109–123

Acknowledgements

We thank the editor, the associate editor, and the anonymous referees for their valuable time and careful comments on our paper, which have led to an improved version of it. We acknowledge a valuable discussion with Professor S. Sriboonchitta. Cathy W.S. Chen’s research is funded by the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (MOST107-2118-M-035-005-MY2).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

We assume \({\varvec{\phi }}_{1}\) \(\sim\) N\(({\varvec{\phi }}_{10},{\varvec{\varSigma }}_1)\). Let \({\varvec{\theta }}_{-{\phi }}\) be the parameter vector excluding the element \({\varvec{\phi }}\). The conditional posterior distribution of \({\varvec{\phi }}_{1}\) is :

In this case, when \(\varepsilon _t\) is a normal distribution, we can write the conditional posterior as:

and

The definitions of \({\varvec{Z}}\), \(\varvec{r}\), and \({\varvec{H}}\) for regime I are as follows.

The conditional posterior in Eq. (8) is not a standard form. We employ it to obtain new estimates. In other words, we draw estimates \({\varvec{\phi }}_{1}\) from a truncated Gaussian density \(N_{B_1}({\varvec{\phi }}^*,{\varvec{\varSigma }}^*)\), where \(B_1=\{ |\phi _1^{(1)}|<1\}\), to get new iterates and apply the random walk MH algorithm to decide whether or not to update the previous estimates. One can usually select a suitable value with good convergence properties by having an acceptance rate of 25–50%, as Gelman et al. (1996) indicate, which represents good convergence performance.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, C.W.S., Lee, B. Bayesian inference of multiple structural change models with asymmetric GARCH errors. Stat Methods Appl 30, 1053–1078 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10260-020-00549-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10260-020-00549-z