Abstract

An analytical and a numerical model are used to understand the response of velocity and sediment distributions over Gaussian-shaped estuarine cross-sections to changes in tidal forcing and water depth. The estuaries considered here are characterized by strong mixing and a relatively weak along-channel density gradient. It is also examined under what conditions the fast, two-dimensional analytical flow model yields results that agree with those obtained with the more complex three-dimensional numerical model. The analytical model reproduces and explains the main velocity and sediment characteristics in large parts of the parameter space considered (average tidal velocity amplitude, 0.1–1 m s − 1 and maximum water depth, 10–60 m). Its skills are lower for along-channel residual flows if nonlinearities are moderate to high (strong tides in deep estuaries) and for transverse flows and residual sediment concentrations if the Ekman number is small (weak tides in deep estuaries). An important new aspect of the analytical model is the incorporation of tidal variations in the across-channel density gradient, causing a double circulation pattern in the transverse flow during slack tides. The gradient also leads to a new tidally rectified residual flow component via net advection of along-channel tidal momentum by the density-induced transverse tidal flow. The component features landward currents in the channel and seaward currents over the slopes and is particularly effective in deeper water. It acts jointly with components induced by horizontal density differences, Coriolis-induced tidal rectification and Stokes discharge, resulting in different along-channel residual flow regimes. The residual across-channel density gradient is crucial for the residual transverse circulation and for the residual sediment concentration. The clockwise density-induced circulation traps sediment in the fresher water over the left slope (looking up-estuary in the northern hemisphere). Model results are largely consistent with available field data of well-mixed estuaries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Estuarine field studies reveal that tidal and residual currents vary considerably between cross-sections and in individual cross-sections over time (Friedrichs and Hamrick 1996; Chant and Wilson 1997; Valle-Levinson et al. 2000; Cácares et al. 2003). The residual suspended sediment concentration typically shows pronounced variations in the across-channel and vertical direction as well (e.g. Nichols 1972; Geyer et al. 1998; Fugate et al. 2007).

Understanding the transverse distributions of flow and sediment is of considerable ecological and economical importance. For example, the transverse structure of estuarine flows seems to significantly affect the along-channel transport of salt, contaminants and suspended sediment (Lacy et al. 2003; Lerczak and Geyer 2004, and references therein). High suspended sediment concentrations reduce biological activities (May et al. 2003; Talke et al. 2009) and cause siltation of navigation channels (De Jonge 2000).

To gain more physical understanding of the transverse distributions of flow and sediment in estuaries, several models have been developed. Most studies focus on the hydrodynamics (Wong 1994; Kasai et al. 2000; Lacy and Monismith 2001; Lerczak and Geyer 2004; Winant 2007, 2008; Li et al. 2008; Valle-Levinson 2008; Huijts et al. 2009). Several studies examine the lateral trapping of sediment as well (Huijts et al. 2006; Chen and Sanford 2009; Chen et al. 2009; Schramkowski et al. 2010). However, no studies have systematically explored how and why transverse distributions of flow and sediment respond to changes in tidal forcing or water depth. This is relevant, because tidal strength and water depth may vary considerably between estuarine cross-sections and in cross-sections over time. The present study therefore aims at quantifying and understanding the sensitivity of transverse patterns of flow and sediment to tidal forcing and water depth. This will be done for estuarine cross-sections where observed along-channel density gradients are of order \(1~\times~10^{-4}~\text{kg}\,\text{m}^{-4}\). A prototype example of such a system is the Western Scheldt estuary in the southwest of the Netherlands (cf. Arndt et al. 2007).

Two different shallow water models are used, which are a two-dimensional analytical model (assuming along-channel uniform conditions) and a three-dimensional numerical model. The former model is suited for sensitivity studies, as it is fast and flexible. In addition, its results can be decomposed into components induced by individual forcing mechanisms, such that effects of individual forcing mechanisms are identified systematically. The numerical model yields more realistic flow fields, as it solves the full three-dimensional shallow water equations and it is prognostic (rather than diagnostic) in the density. Horizontal density gradients, tidal discharge and Stokes discharge obtained with the numerical model are used as input for the analytical model. Both models use the same simple sediment transport model.

The analytical model applies to tidally dominated estuaries with arbitrary across-channel bed profile. Forcing conditions and bathymetry are assumed to be uniform in the along-channel direction. Density is prescribed and assumed to be well mixed over the vertical. The model extends that of Huijts et al. (2009): inspired by field data (Fugate et al. 2007; Kim and Voulgaris 2008), it accounts for semi-diurnal tidal variations in the across-channel density gradient. The baroclinic forcing introduces a new transverse tidal flow component as well as a new tidally rectified along-channel residual flow component. A Stokes discharge component is added here as well. Other forcing mechanisms in the analytical model are related to tidal forcing, residual horizontal density gradients, Coriolis-induced tidal rectification and the earth’s rotation. The numerical model used in this study is TRIWAQ (see e.g. Stelling 1984).

The previous analytical models were able to reproduce important features of flow and sediment distributions observed in several estuarine cross-sections. However, differences between model results and field data were also reported. These differences may be related to model assumptions that are not satisfied in a particular estuarine cross-section. This study therefore also investigates in what physical conditions the new analytical model yields reliable results.

Section 2 introduces the analytical and numerical model. Section 3 compares numerical and analytical velocity and sediment distributions for a range of conditions representing weak to strong tides in shallow to deep estuaries with a Gaussian-shaped cross-section. Particular focus is on the along-channel and transverse components of the residual and semi-diurnal tidal flow and the residual suspended sediment concentration. It is identified in what areas of the parameter space the analytical model performs well. In these areas, the variations of flow and sediment distributions to changes in tidal forcing and water depth is explained by using the individual forcing components in the analytical model. Section 4 discusses why the numerical and analytical model disagree in particular conditions. The new density-induced tidal rectification mechanism is examined in more detail, and it is discussed what potentially important mechanisms have not been examined in this study. Conclusions are given in Section 5.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Analytical flow model

The 2DV analytical flow model is derived from equations that describe tidal and residual flow in an estuarine cross-section with arbitrary bed profile. A Cartesian coordinate system (x,y,z) is used, where x is seaward, y is to the left if looking seaward and z is up (Fig. 1a). The location of the undisturbed water level is at z = 0. The equations of motion read

which are the horizontal momentum equations and a continuity equation. Here, t is time, u, v and w are the velocity components in the x-, y- and z-direction and η is the location of the free surface. The state variables are the velocity components u, v, w and the free surface gradients \({\partial\eta}/{\partial x},\) \({\partial\eta}/{\partial y}\). The model assumes that these variables do not vary in the along-channel direction. Furthermore, \(\rho=\rho_0+{\tilde\rho}(x,y,t)\) is the density, with ρ 0~1,\(000~\text{kg}~\text{m}^{-3}\) a reference density and \(\tilde\rho\) a density fluctuation that varies with salinity. Finally, \(g\sim 10~\text{m~s}^{-2}\) is the gravitational acceleration, f~10 − 4 s − 1 is the Coriolis parameter and \(A_z\sim 10^{-3}~\text{m}^2~\text{s}^{-1}\) is the vertical eddy viscosity coefficient. The model is diagnostic in the density, i.e., the along-channel and across-channel density gradients are prescribed.

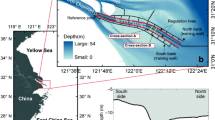

Sketch of the geometry of a the 2DV-analytical model and b the 3D-numerical model. The arrow indicates the Gaussian cross-section for which numerical model results are presented. The cross-section is situated at 800 km from the river boundary. Model geometries and variables are described in the main text

The corresponding boundary conditions are that the flow at the bed satisfies the no-slip condition and there is no flow through the bed,

At the surface, we assume that the water motion is stress free and satisfies the kinematic boundary condition. Using the rigid lid approximation (free surface variations are small compared with the water depth) yields

A semi-diurnal tidal discharge Q t = UA and a residual discharge Q s are imposed by

where U is the cross-sectionally averaged tidal velocity amplitude, A is the cross-sectional area and ω ~1.4×10 − 4 s − 1 is the angular frequency of the semi-diurnal tide.

There is no across-channel transport of water through the sides (y = 0 and y = B). It then follows from integration of the continuity equation (1c) and application of the appropriate boundary conditions that the across-channel transport of water vanishes anywhere in the cross-section,

Finally, a simple closure relation for the eddy viscosity coefficient A z is adopted, based on concepts discussed by Bowden et al. (1959), i.e.,

where we use \(c_v=2\times10^{-3}\) and H 0 is the mean depth of the cross-section.

The velocity is thus forced by a semi-diurnal tidal discharge, a residual discharge and by along- and across-channel gradients in water density. The density gradients are assumed to be independent of the vertical coordinate z, hence well-mixed conditions are considered. The along-channel density gradient consists of a residual component. The across-channel density gradient includes a residual component and a component that varies at the semi-diurnal tidal timescale. The latter component has not been considered in analytical studies before.

The next step in deriving reduced model equations concerns the formulation of assumptions with regard to the relative magnitude of different flow components. Consequently, not all terms in the equations above are of equal magnitude. This information can be subsequently used to derive approximate, analytical solutions. To proceed, define U and V as magnitudes of flow in the x and y direction, respectively. The key assumptions are now twofold. First, V ≪ U, which allows for the definition of ε ≡ V/U, where ε ≪ 1. Second, the along-channel residual flow is an order ε smaller than the along-channel tidal flow.

Approximate solutions of the equations are constructed as perturbation series in the small parameter ε. To lowest order this yields the equations for tidal flow variables, whilst at the next order the equations governing the residual flow are found. They are discussed in the next subsections.

2.1.1 Tidal flow

The semi-diurnal tidal flow is described by

Primes denote semi-diurnal tidal components.

The boundary conditions at surface and bottom, and the constraint on the across-channel tidal flow are identical to those of the total flow, as discussed above. A semi-diurnal tidal discharge is imposed by

The along-channel semi-diurnal tidal flow thus consists of a single component that is forced by the semi-diurnal tidal discharge. The transverse tidal flow consists of two components,

where (v f ′, w f ′) is a flow component induced by Coriolis forcing of the along-channel tidal flow (Coriolis-induced component) and (v ρ ′, w ρ ′) is a flow component forced by the semi-diurnal across-channel density gradient (density-induced component). The solution for the Coriolis-induced transverse tidal flow component can be found in Huijts et al. (2006). The density-induced transverse tidal flow component is new. The analytical solution for this component is presented in the Appendix.

2.1.2 Residual flow

The along-channel residual flow is described by

The bar denotes residual (tidally averaged) components. Again, boundary conditions at surface and bottom and the constraint on the across-channel flow are similar as those of the full flow. The corresponding constraint on the volume discharge is

The along-channel residual flow can be decomposed into four components,

The terms on the right-hand side represent the components that are forced by the residual along-channel density gradient, the Stokes discharge and two tidal rectification processes. Analytical solutions of the first three flow components were presented and discussed in Huijts et al. (2009). This includes \({\bar u}_\text{rect1}\), which is a tidally rectified along-channel flow that results from net advection of along-channel tidal momentum by Coriolis-induced transverse tidal currents. The fourth component, \({\bar u}_\text{ rect2}\), is a new tidal rectification process that results from net advection of along-channel tidal momentum by the density-induced transverse tidal flow.

The across-channel residual flow is decomposed into two components,

which are induced by Coriolis forcing of the along-channel residual flow (Coriolis-induced component) and by the residual across-channel density gradient (density-induced component).

The analytical model solutions apply to arbitrary across-channel bed profiles. In this study, the solutions are examined for a symmetric, single channel cross-section represented by a Gaussian-shaped bed profile (Fig. 1a),

In this expression, L is a bathymetric steepness parameter that determines the steepness of the across-channel bed profile. The steepness parameter is determined by the maximum and the minimum water depth in the cross-section.

2.2 Numerical flow model

The numerical model used in this study is TRIWAQ. The full nonlinear three-dimensional shallow water equations are solved using a finite difference method. In contrast to the analytical model, the numerical model also solves the salt balance equation, it uses a free surface and it allows for along-channel variations in the bed profile. The numerical model is set-up such that the velocity field, surface gradients and density gradients in the Gaussian cross-section at 800 km from the river boundary are approximately uniform in the along-channel direction. To this end, the model geometry is 1,200 km long and 5 km wide (Fig. 1b). It consists of a landward, an intermediate and a seaward region. In the landward part (first 500 km), the bottom has a constant slope in the along-channel direction, but depth does not vary in the across-channel direction. In the seaward part (last 100 km), the bottom is flat and horizontal. In the middle of the intermediate region (at 800 km from the landward boundary), the cross-section adopts the Gaussian-shaped bed profile as used in the analytical model. From there, the cross-section gradually changes over 300 km to the rectangular shapes of the landward and seaward region. The gradual changes in bathymetry allow the flow and salinity to adjust smoothly, such that velocity field and density gradients are approximately along-channel uniform in the Gaussian cross-section of interest. The domain is discretized using an orthogonal grid in the horizontal direction. The along-channel and across-channel grid size is 2.5 km and 250 m, respectively. Ten sigma layers are used in the vertical direction. From bed to surface, the layer thickness increases from 2% to 20% of the instantaneous and local water depth.

At the seaward boundary, an across-channel uniform sea surface is imposed that varies on the semi-diurnal tidal timescale, as well as a salt water salinity of 33.5 PSU. At the landward boundary, a vanishing river discharge is imposed as well as a fresh-water salinity of 0.5 PSU. A large horizontal eddy diffusion coefficient is used in the landward and seaward regions (Fig. 1b), such that the landward and seaward regions contain pure river or sea water. A horizontal eddy diffusion coefficient of \(10~\text{m}^2~\text{s}^{-1}\) is used in the intermediate zone, such that the density varies approximately linearly in the along-channel direction. By setting the extent of the intermediate zone, the numerical model is thus designed to generate a user-controlled value of the along-channel density gradient at the estuarine cross-section.

The closure scheme for vertical eddy viscosity and eddy diffusivity is identical to that used in the analytical model. Boundary conditions at the surface and bed are similar to those of the analytical model. The analytical model condition that there is no net mass transport through the sides, which results in condition (5), is not available in the numerical model. Instead, the numerical model requires that the across-channel velocity vanishes at impermeable walls. The different condition at the sides is not expected to cause significant differences in the flow fields, as velocities over the shallow sides are small.

2.3 Sediment model

Velocity fields obtained with the analytical and with the numerical model are used to compute transverse distributions of suspended sediment. A simple sediment model from Huijts et al. (2006) is adopted. The model considers non-cohesive sediment that is represented by a single settling velocity. The sediment mass balance equation reads

where c is either a residual component of the suspended sediment concentration, \(\bar c\), or a tidal component, c′. The settling velocity \(w_s\sim 0.3~\text{mm}~\text{s}^{-1}\) and the vertical diffusion coefficient for the sediment K z is assumed to be equal to the vertical eddy viscosity coefficient A z (6). We impose no sediment flux through the surface,

The entrained flux of sediment at the bed varies with the local bed shear stress τ b and availability of bed sediment a(y),

Here, ρ s and d s are the grain density and size, and g′ = g(ρ s − ρ 0)/ρ 0 is the reduced gravity. The absolute value of the bed shear stress is given by

where u is a vector containing the horizontal velocity components. The across-channel availability of sediment a(y) is calculated by imposing a morphodynamic equilibrium condition, as was used first in an along-channel sediment model by Friedrichs et al. (1998). The morphodynamic equilibrium condition ensures that that there is no net erosion or deposition of sediment at the bed, i.e.,

such that the residual bed profile does not evolve over time. The morphodynamic equilibrium condition reads

where \(T_{\text{M}_0}\) and \(T_{\text{M}_2}\) are the net advective sediment transport laterally induced by the residual flow and by the tidal flow, respectively, and \(T_{\text{dif\/f}}\) is the net diffusive transport laterally. In addition, \(K_{h}\sim10\ \text{m}^2\,\text{s}^{-1}\) is a horizontal eddy dispersion coefficient. Note that v′ and c′ are tidal components of velocity and sediment. The analytical model considers semi-diurnal tidal components only, whereas semi-diurnal and quarterly-diurnal tidal constituents are considered to compute sediment concentrations for the numerical flows. Equation 20 reveals that the system is in morphodynamic equilibrium if the net advective sediment transport balances the diffusive transport across the channel. To determine the sediment availability a(y) from the morphodynamic equilibrium condition, the equation is rewritten into a first order linear differential equation (see (12) in Huijts et al. 2006). To solve this equation, the across-channel average sediment availability, a *, has to be prescribed. The parameter a * is thus a tuning parameter (i.e., the scale of sediment concentrations is arbitrary).

Analytical solutions for the residual and for the semi-diurnal component of the suspended sediment concentration are given in the previously cited study. The residual and tidal component of the bed shear stress (18) and the morphodynamic equilibrium condition (20) for the analytical flow are computed from tidal and residual velocity components. Residual and tidal components of the numerical bed shear stress (18) are calculated directly from the full numerical flow fields.

2.4 Methods

Numerical and analytical experiments are performed for different estuarine conditions representing weak to strong tides in shallow to deep estuaries. This is done by varying the cross-sectionally averaged tidal velocity amplitude U and the maximum water depth \(H_\text{max}\). Both models use a single, fixed value for the average sediment availability a *, and for the channel width B and the minimum water depth \(H_\text{min}\) of the Gaussian cross-section (see Fig. 1).

Note that our numerical model is designed to generate a user-controlled value of the along-channel density gradient at the cross-section that we consider. Such an approach is also employed in other studies (cf. Burchard et al. 2011). Horizontal density gradients, mean tidal velocity amplitude and Stokes discharge are calculated from numerical model results and used as input for the analytical model. The Stokes discharge Q s is computed from numerical model results as follows,

In this expression, the semi-diurnal component of the along-channel velocity u ′ is evaluated at the surface z = 0, and η ′ is the semi-diurnal component of the free surface. Thus, Q s compensates for the net volume transport that is induced by the (partially) travelling tidal wave in the numerical model.

For each experiment, numerical and analytical model results are compared. Considered are the along- and across-channel components of the residual and tidal flow and the residual suspended sediment concentration. The amount of agreement between numerical and analytical model results is quantified using a correlation and a magnitude coefficient. The correlation coefficient R is used to quantify the amount of agreement in the transverse patterns of a numerical amplitude A N (y,z) and an analytical amplitude A A (y,z),

Here, brackets represent a cross-sectional average value, i.e.,

The correlation coefficient may take any value between 1 and − 1, reflecting a perfectly positive to a perfectly negative linear relationship between the transverse patterns of A N and A A . The magnitude coefficient compares the maximum values of a numerical and an analytical amplitude over the cross-section,

A visual comparison of numerical and analytical model results (tidal components evaluated at flood, ebb and slack tides as well as residual components) revealed that the main features of the numerical results are reproduced relatively well by the analytical model if the correlation coefficient of the amplitudes is larger than 0.7 and the magnitude coefficient of the amplitudes is between 1/3 and 3. Therefore, these values are selected to identify agreement and disagreement areas in the parameter space.

If the main features of a particular flow or suspended sediment component (e.g., the along-channel residual flow) are reproduced by the analytical model in a particular part of the parameter space (agreement area), analytical model results are used to interpret the sensitivity of the particular component to changes in tidal forcing and water depth in terms of physical mechanisms (Section 3). For the tidal forcing and water depth conditions in which the analytical model is not able to reproduce the main characteristics of a particular numerical flow or sediment component well enough (disagreement area), numerical and analytical model results are combined to investigate what physical mechanisms that are not in the analytical model are likely to be important for that component in those conditions (Section 4).

3 Results

A series of 25 experiments was performed with the numerical and with the analytical model. Numerical model results are presented for the estuarine cross-section with a Gaussian shape that is located at 400 km from the seaward boundary (Fig. 1b). The two input parameters that were varied are the maximum water depth of the Gaussian cross-section, \(H_\text{max}\), which was approximately 10, 15, 30 and 60 m and the cross-sectionally averaged tidal velocity amplitude U, which was around 0.1, 0.3, 0.6 and 1 ms − 1. The cross-sectional width was fixed at B = 5 km and the minimum water depth \(H_\text{min}=2\) m. Furthermore, the tidal frequency ω = 1.4×10 − 4 s − 1, the Coriolis parameter f = 1×10 − 4 s − 1, the horizontal dispersion parameter \(K_h=10~\text{m}^2\,\text{s}^{-1}\) and the settling velocity \(w_s=3\times 10^{-4}~\text{m}~\text{s}^{-1}\). Transverse distributions of velocity and sediment are displayed for a default experiment with \(H_\text{max}=30\) m and U = 0.6 ms − 1.

Important dimensionless numbers are related to the parameters U (via Eq. 6) and \(H_\text{max}\),

which are the Ekman number, the Stokes number and the inverse Strouhal number, respectively. Here, V is the maximum across-channel tidal velocity amplitude of a numerical experiment, and \(L_y=L^2/B\) is a bathymetric length scale that characterizes the across-channel variations in the bed profile (see Eq. 14). The Ekman number measures the ratio of the internal friction force and the Coriolis force, whilst the Stokes number represents the ratio of the oscillatory boundary layer thickness to the maximum water depth. Finally, the inverse Strouhal number NL measures the relative importance of the nonlinear advection terms and the local inertia (or tendency) term in the along-channel momentum equation (1a). The experiments cover Ekman numbers from 0.01 to 1 (not shown) and Stokes numbers from 0.1 to 0.6 (Fig. 2). The values of the inverse Strouhal number range from 0.1 (linear regime) to 2.5 (nonlinear regime).

Sensitivity of a the Stokes number and b the inverse Strouhal number as defined in Eq. 25 to changes in the cross-sectional mean tidal velocity amplitude U and maximum water depth \(H_\text{max}\). The Ekman number is not shown here, as it is closely related to the Stokes number. Black dots in these and subsequent figures represent the tidal forcing and water depth conditions that are used in the experiments. The large dot represent the default experiment (\(H_\text{max}=30~\) m and U = 0.6 m s − 1), for which E = 0.2, St = 0.4 and NL = 1.0

Results are presented as follows. Section 3.1 describes the numerical model output that is used as input for the analytical model. This concerns the along-channel residual density gradient, the Stokes discharge and the residual and tidal components of the across-channel density gradient. In Section 3.2, analytical and numerical velocity and sediment distributions over the cross-sections are compared for a range of tidal strength and water depth conditions. Agreement areas are identified for the tidal and residual components of the along-channel and the transverse velocity and for the residual suspended sediment concentration. In the agreement areas, the response of the transverse distributions of velocity and suspended sediment to changes in tidal forcing and water depth is described (Section 3.2) and explained in terms of physical mechanisms (Section 3.3). Disagreement areas will be discussed in Section 4.

3.1 Horizontal density gradients and Stokes discharge

This section presents input parameters for the analytical model that are calculated using numerical model output. The first parameter is the (cross-sectionally and tidally averaged) along-channel density gradient \(\partial\rho/\partial x\). The gradient is approximately 1×10 − 4 kg m − 4 in large parts of the parameter space, with somewhat smaller values in shallow water for strong tides (Fig. 3a). The gradient in the area of the Gaussian cross-section is approximately constant, because we choose a fixed length of the intermediate zone and a fixed value of the horizontal eddy diffusion coefficient in this zone. These choices have been made to keep the set-up of the experiments as simple as possible. Note that we consider U and \(H_{\text{max}}\) as two independent parameters in our study. We return to this aspect in the discussion. We further remark that the values for \({\partial\rho/\partial x}\), U and \(H_{\text{max}}\) that we use to define our default situation are representative for the lower reach of the Western Scheldt, a well-mixed estuary in the southwestern part of the Netherlands. Indeed, Schramkowski and De Swart (2002) analysed tidal velocity data in this area and found eddy viscosities of order \(0.05~\text{m}^2~\text{s}^{-1}\), whilst along-channel density gradients of order \(1~\times~10^{-4}~\text{kg}~\text{m}^{-4}\) are reported in Arndt et al. (2007).

Stokes discharge and horizontal density gradients calculated from numerical model output and used as input for the analytical model. Displayed are a the cross-sectional average of the along-channel residual density gradient (in \(\text{kg}~\text{m}^{-4}\)), b the Stokes discharge (in 1,000 m3 s − 1), and c, d residual and e, f tidal components of the vertically averaged across-channel density gradient (in \(\text{kg}~\text{m}^{-4}\)). The contour plots show how magnitudes vary with tidal forcing and water depth. c, e Maximum density gradients. d Across-channel profiles of the residual across-channel density gradient. The solid line (default experiment) is representative for most runs in the agreement area of the across-channel residual flow (see Section 3.2.2). Two runs in this agreement area, U = 0.1 ms − 1 and \(H_\text{max}=10,15\) m, have a different profile (dashed line). f The across-channel profiles of the tidal gradient at maximum flood (dotted line) and at high water slack (solid line) for the default experiment. The profiles are representative for the entire agreement area of the across-channel tidal flow

The second parameter, the Stokes drift, increases from almost zero for weak tides to 5 ×103 m3 s − 1 for strong tides (Fig. 3b). Both the residual along-channel density gradient and the Stokes drift force the along-channel residual flow in the analytical model.

Next, the depth- and tidally averaged across-channel density gradient is considered, which forces the transverse residual flow in the analytical model. Its magnitude and across-channel profile are presented in Fig. 3c and d. The solid line in panel d is obtained from the default experiment (\(U=0.6~\text{ms}^{-1}\) and H = 30 m) and is representative for most experiments in the agreement-area of the across-channel residual flow (see Section 3.2.2). The profile reflects that water density increases towards the right (looking into the estuary) and that the largest density gradients occur in the channel. The dashed line represents a different profile that is found for small tidal flow and water depth conditions (\(U=0.1~\text{ms}^{-1}\), \(H_\text{max}=10,15\) m). For these conditions, the maximum density occurs in the central region of the cross-section. The physics resulting in these characteristics is discussed in Section 3.3.1.

Finally, the tidal component of the across-channel density gradient is shown in Fig. 3e, f. The gradient is small during maximum flood and ebb (dotted line) but significant during slack tides (solid line). Its magnitude increases with tidal forcing and water depth. During slack tides, the largest gradients are found over the slopes and are of opposite sign.

3.2 Transverse distributions of flow and sediment

3.2.1 Tidal velocity

The along-channel tidal velocity computed with the analytical and numerical model agree well in the entire parameter space. The correlation coefficient of the tidal velocity amplitude is always above 0.99, and the magnitude coefficient ranges between 0.95 and 1.03 (not shown), indicating that the models agree both on the transverse pattern and on the magnitude of the along-channel tidal velocity in the entire parameter space.

The transverse structure of the along-channel tidal flow varies with the Stokes number. Figure 4 displays a typical pattern for moderate to large Stokes numbers at maximum flood (left panels) and at high water slack (right panels). Top (bottom) panels display numerical (analytical) model results. Note that the numerical model results show a cut-off region near the surface. This is because variations of the free surface cause points near the surface to be submerged during part of the tidal cycle. In the analysis, points which are dry during more than 30% of the tidal cycle have been left out. The along-channel tidal flow pattern features currents increasing from bed to surface and reversing earlier close to the bed than higher up in the water column. The ebb and low water slack pattern of this and other semi-diurnal quantities is equal and opposite to the flood and high water slack pattern. For small Stokes numbers, the velocity distribution becomes almost uniform in the interior, and velocity shear is confined to a thin boundary layer near the bottom (not shown).

Along-channel semi-diurnal tidal velocity at maximum flood (left panels) and at high water slack (right panels) obtained with the numerical model (top panels) and with the analytical model (bottom panels) in cm s − 1. The patterns are shown for the default experiment, which are representative for most of the parameter space (except for the smallest Stokes numbers, see text). Orientation of this and subsequent figures is looking landward. Positive (red) currents are seaward, whereas negative (blue) currents are landward. Note the difference in scale between the across-channel and the vertical axis. The numerical model results show a cut-off region near the surface: points which are dry during more than 30% of the tidal cycle are not considered as part of the model domain

Next, results are presented for the across-channel and vertical components of the semi-diurnal tidal flow (Fig. 5). Panels a and b show that the correlation and magnitude coefficients are sufficiently close to 1 (above 0.7 and between 1/3 and 3, respectively; see Section 2.4) in large parts of the parameter space. A small disagreement area can be identified for the across-channel tidal velocity for weak tidal forcing in large water depth (i.e., small Stokes numbers). The disagreement area is displayed in panel c and other figures by a gray-shaded area to indicate where analytical model results of this component are not satisfactory (as will be done for disagreement areas of other velocity and sediment components).

Variability of agreement coefficients, magnitude and transverse patterns of the transverse semi-diurnal tidal velocity with changes in tidal forcing and water depth. a Correlation coefficient; contour interval is 0.05 and values larger than 0.7 indicate agreement about the numerical and the analytical pattern. b Magnitude coefficient; values between 1/3 and 3 indicate agreement about the order of magnitude of the currents. c Largest across-channel tidal velocity in the numerical experiments in cm s − 1. The gray-shaded area indicates disagreement (see Section 2.4). Transverse structure of the across-channel tidal velocity d at maximum flood and e at high water slack computed with the numerical (top) and analytical (bottom) model. The patterns are displayed for the default experiment, which are representative for the agreement area. Positive (red) represents currents to the left (looking landward), whereas negative (blue) are currents to the right. Transverse circulation patterns are represented by schematic arrows

Figure 5c shows that across-channel tidal currents increase with tidal forcing and water depth. Typical transverse distributions of the lateral tidal flow at maximum flood and at high water slack are shown in Fig. 5d, e. Both models show a single cell circulation pattern during flood and ebb, and two counter-rotating circulation cells during slack tides. The double circulation pattern was not found with earlier analytical models (Huijts et al. 2006, 2009).

3.2.2 Residual velocity

The correlation between the along-channel residual velocity in the analytical and numerical experiments is shown in Fig. 6a. The correlation coefficient is generally high (above 0.7), indicating that the analytical model captures the main characteristics of the along-channel residual flow pattern quite well in large parts of the parameter space. The magnitude coefficient in panel b shows that the magnitude of the along-channel residual flow is also well modelled, except for strong tides in deep water (the nonlinear regime, see Fig. 2).

Variability of agreement coefficients, magnitude and transverse pattern of the along-channel residual velocity with changes in tidal forcing and water depth. a Correlation coefficient. b Magnitude coefficient. c Maximum along-channel residual velocity in the numerical experiments in cm s − 1. Note the presence of two regimes with opposite dependence of the maximum along-channel residual flow on tidal forcing. Regimes I and II represent weak tides and stronger tides, respectively. d Distribution of the along-channel residual velocity over the cross-section for the default experiment, computed with the numerical (top) and analytical (bottom) model. Orientation is looking landward; blue (red) colours indicate landward (seaward) flow. Note that the transverse patterns differ over the agreement area as described in the main text

Figure 6c reveals two major regimes in the along-channel residual velocity. In regime I (weak tides, U < 0.3 m s − 1), the along-channel residual flow decreases with tidal forcing, whereas in regime II (stronger tides, U > 0.3 m s − 1) it increases with tidal forcing. In both regimes, along-channel residual velocities increase with water depth. This behaviour will be explained in Section 3.3.3. We already remark here that the value of U that separates the two regimes applies depends on the along-channel density gradient that is imposed. Here, this gradient is of order \(1 \times 10^{-4}~\text{kg}\,\text{m}^{-4}\), which is representative for the Western Scheld, whilst in estuaries like the Hudson and James River this gradient is often stronger. This issue is further discussed in Section 4.

The transverse pattern of the along-channel residual flow significantly varies with tidal forcing as well. In the weak tidal regime, the along-channel residual flow is relatively symmetric about the mid-axis of the channel. Currents are landward in the channel and seaward over the shoals (not shown). For stronger tides (e.g., in the default case), the pattern is more anti-symmetric about the mid-axis of the channel (Fig. 6d). Currents are generally landward in the right and seaward in the left part of the cross-section (looking landward in a Northern Hemisphere estuary), with stronger seaward than landward currents. An exception is found for strong tides in shallow water, where the along-channel residual velocity resembles a river flow.

Next, the across-channel residual velocity is considered in Fig. 7. The top panels display the sensitivity of the correlation and magnitude coefficients to tidal forcing and water depth. The panels reveal that the analytical model captures the main features of the across-channel residual flow (following the correlation and magnitude criteria introduced in Section 2.4) in large parts of the parameter space. Disagreement is found for weak tides in deep water (i.e., small Ekman and Stokes numbers).

Variability of agreement coefficients, magnitude and transverse pattern of the transverse residual velocity, displayed as in Fig. 6. In (d), orientation is looking landward. The patterns shown here are representative for the entire agreement area, except for weak tides in shallow water (see main text)

The across-channel residual velocity increases with tidal strength and water depth (Fig. 7c). In the agreement area, the transverse pattern generally features a single clockwise circulation (looking landward in a Northern Hemisphere estuary), as it is shown for the default experiment in Fig. 7d. Exceptions occur in the case of weak tides in shallow water (U = 0.1 ms − 1 and \(H_{\text{max}}=10\) and 15 m), where the transverse residual velocity is characterized by two counter-rotating circulation cells.

3.2.3 Sediment distribution

The top panels of Fig. 8 show the correlation and magnitude coefficients of the residual suspended sediment concentration. Analytical and numerical sediment patterns agree well in large parts of the parameter space. Disagreement occurs for small Stokes and Ekman numbers, and for strong tides in shallow water.

Variability of agreement coefficients, magnitude and transverse pattern of the residual suspended sediment concentration in mg l − 1, displayed as in Fig. 6. The transverse sediment pattern in (d) is shown for the default experiment, which are representative for the agreement area. Here, orientation is looking landward. Recall that the average sediment availability is prescribed (Section 2.3; fixed value for all experiments). The scale of the sediment concentration is therefore arbitrary

In the agreement regime, residual sediment concentrations roughly increase with tidal forcing (panel c). The transverse structure is similar to the pattern for the default experiment shown in panel d. The panel shows that sediments trapping occurs over the left slope of the channel.

3.3 Analysis of density, flow and sediment distributions

This section aims at explaining the response described above of density, flow and sediment patterns to changes in tidal forcing and water depth. This is done by decomposing analytical velocity constituents (e.g., the along-channel residual flow) into components induced by individual mechanisms. The individual components are discussed and used to explain the variability of a particular constituent with changes in tidal forcing and water depth. Focus is still on the agreement areas.

3.3.1 Density distribution

Although the focus of this study is not on the density field, as the analytical model is diagnostic in the density, it is important to discuss briefly the characteristics of the density field, as calculated by the numerical model, which is used as input in the analytical model. Figure 3d shows that for the default parameter setting, a positive mean lateral density gradient occurs over the cross-section. Thus, water is denser in the channel and towards the right bank than in the area near the left bank (when looking into the estuary). There are two processes that contribute to this distribution. First, the along-channel residual flow induces advection of mean salinity. As landward flow occurs in and to the right of the channel and outflow near the left bank (see Fig. 6d), this leads to saltier water at the right of the cross-section and fresher water at the left. Second, as explained in Schramkowski et al. (2010), the correlation between the transverse tidal flow and the tidal component of the density field causes a net density flux towards the right bank. The more symmetrical lateral density profile in Fig. 3d, which occurs for smaller depth and weaker tidal flow, represents denser water in the channel. This is caused by a more symmetrical along-channel residual flow (discussed below), with inflow in the channel and outflow over the shoals.

The tidal across-channel density gradient, as it is shown in Fig. 3f, seems to be related to differential advection of salt water by the along-channel tidal flow (Nunes and Simpson 1985; Lerczak and Geyer 2004). As tidal currents are generally stronger in deeper water, the semi-diurnal component of the density field is high (low) in the deep channel and lower (higher) towards the shallower sides. At the end of a flood tide or ebb tide, differential advection has resulted in maximum density differences between channel and the shoals. The result are lateral density gradients (solid line in Fig. 3f) that are strong compared with those at maximum flood or maximum ebb (dashed line in Fig. 3f).

3.3.2 Tidal flow mechanisms

Section 3.2.1 showed that the analytical model was able to capture the main characteristics of the numerical along-channel tidal flow over the entire parameter space. The along-channel tidal flow obtained with the analytical model consists of a single component, which is forced by a semi-diurnal tidal discharge (Eq. 8). The good agreement thus reveals that local inertia, the barotropic pressure gradient and friction (Eq. 7a) capture the dominant balance for the parameter range considered here. Other terms including the Coriolis and advection terms thus play a minor role for the along-channel tidal flows here.

To understand the sensitivity of the transverse tidal velocity to tidal forcing and water depth, as it is described in Section 3.2.1, the analytical across-channel tidal velocity is decomposed into a Coriolis-induced component, v f ′, and a density-induced component, v ρ ′ (see Eq. 9). The two components are induced by Coriolis deflection of the along-channel tidal flow and by the lateral tidal density gradient, respectively. The Coriolis-induced transverse tidal currents increase with tidal forcing and water depth (Fig. 9a), whereas the density-induced transverse tidal currents increase with water depth only (Fig. 9b). The Coriolis-induced component is larger than the density-induced component in large parts of the parameter space (except for small Ekman and Stokes numbers). However, the density-induced component significantly affects the transverse tidal flow in large parts of the parameter space as well. The increase of the across-channel tidal velocity with tidal forcing (Fig. 5c) is thus caused by the Coriolis-induced component (Fig. 9a). The increase with water depth in Fig. 5c is a result of both mechanisms. Note that the competition between the Coriolis-induced component and the density-induced component seems to vary with the Ekman and Stokes numbers (compare Fig. 2a to the dashed contours in Fig. 9a, b). This also implies that the relative importance of the density-induced component increases from spring to neap tide (represented by a decrease in tidal velocity and constant water depth).

Physical components of the transverse tidal velocity in the analytical model. The components are forced by Coriolis deflection of the along-channel tidal flow (left panels) and by the semi-diurnal component of the across-channel density gradient (right panels). Top panels display the magnitude (largest current in cm s − 1) as a function of tidal strength and water depth. Dashed contours indicate the relative contribution of the components (in %). Middle panels show the transverse patterns at maximum flood (orientation is landward) for the default experiment, which are representative for the agreement area. Bottom panels show the transverse patterns at high water slack

The Coriolis-induced component of the transverse tidal flow typically features a single circulation cell, as is shown for maximum flood in Fig. 9c, and at high water slack in Fig. 9e. The density-induced transverse tidal flow is very weak at maximum flood (Fig. 9d), whilst at high water slack it is significant and organized in two counter-rotating cells (Fig. 9f). During flood and ebb, the Coriolis-induced component of the transverse tidal flow is dominant over the density-induced component. Both components contribute significantly to the transverse tidal flow during slack tides. The Coriolis mechanism considered here thus causes the single transverse tidal circulation pattern during ebb and flood (Fig. 5c), and the dominant cell during slack tides (Fig. 5d). Tidal variations in the across-channel density gradient cause the double circulation pattern during slack tides (Fig. 5d).

3.3.3 Residual flow mechanisms

To understand the variability of along-channel residual flow as described in Section 3.2.2, the analytical along-channel residual flow is decomposed into four components (Eq. 12). The components are forced by the along-channel residual density gradient, \({\bar u}_{\partial\rho/\partial x}\), Stokes discharge, \({\bar u}_{\rm St}\), Coriolis-induced tidal rectification, \({\bar u}_\text{rect1}\) and density-induced tidal rectification, \({\bar u}_\text{rect2}\). Recall that the Coriolis-induced (density-induced) tidally rectified flow component originates from net advection of along-channel tidal momentum by the Coriolis-induced (density-induced) transverse tidal velocity (Section 2.1.2).

Figure 10 presents the transverse patterns (top and bottom panels) and magnitudes (middle panels) of the four individual flow components. The transverse patterns are displayed for the default experiment, but are representative for all experiments in the agreement area. The density driven flow pattern is characterized by landward flow in the channel and seaward flow over the shallower sides (panel a). The density driven currents increase with a decrease in the Stokes number (panel c). The Stokes return flow is seaward over the entire cross-section as shown in b and is stronger for larger tides in shallower water (panel d). The Coriolis-induced tidally rectified flow component is characterized by landward flow in the right part of the domain and seaward flow in the left part (looking up-estuary in the northern hemisphere) and is therefore anti-symmetric with respect to the center axis (panel g). In contrast, the density-induced tidally rectified flow is symmetric with respect to the center axis, with landward flow in the deeper part of the channel, flanked by narrow regions of seaward flow over the shoals (panel h). The tidally rectified flows increase with tidal forcing and water depth as shown in panels e and f. The first three mechanisms have been discussed in Huijts et al. (2006, (2009). The new density-induced tidal rectification mechanism will be explained in Section 4.2.

Physical components of the along-channel residual velocity in the analytical model. The components are forced by the along-channel residual density gradient (top left panels), Stokes discharge (top right panels), Coriolis-induced tidal rectification (bottom left panels) and density-induced tidal rectification (bottom right panels). The tidal rectification mechanisms result from net advection of along-channel tidal momentum by the Coriolis-induced transverse tidal flow and by the density-induced transverse tidal flow, respectively. Inside panels display the magnitude (largest current in cm s − 1) as a function of tidal strength and water depth. Dashed contours indicate the relative contribution of the components (in %). Outside panels show the transverse patterns for the default experiment (orientation is looking landward), which are representative for the agreement area. Blue (red) colours indicate landward (seaward) flow

Two major regimes were identified in Section 3.2.2 for the along-channel residual velocity. In the weak tidal regime (\(U<0.3~\text m~\text{s}^{-1}\), for our value of the along-channel density gradient), the residual currents were landward over the channel and seaward over the shoals and stronger for weaker tides in deeper water (i.e., Ekman number smaller). Figure 10a and c reveal that this variability is caused by the along-channel density gradient, which is the dominant forcing in the weak tidal regime. In the stronger tidal regime (\(U>0.3~\text{m}~\text{s}^{-1}\)), the residual currents were generally landward to the right and seaward to the left with relatively strong seaward currents and increased with tidal forcing and water depth (i.e., a larger inverse Strouhal number). Figure 10e and f reveal that these characteristics are caused by the two tidal rectification mechanisms. In particular, the Coriolis-induced component causes the anti-symmetric pattern, whereas the density-induced component explains the relatively strong seaward currents. Note that the density-induced tidal rectified flow is particularly important in the deeper experiments (\(H_\text{max}>30\) m). A third along-channel residual flow pattern was found for strong tides in shallow water. Panels b and d show that this river flow pattern is caused by Stokes return flow. Note the minor role of the along-channel density gradient in the stronger tidal regime. This explains why the classical estuarine scaling, which relates the magnitude of the along-channel residual flow to along-channel density gradients (cf. Hansen and Rattray 1965; Scully et al. 2009), is no longer valid here. Again, we emphasize here that the border between the weak and stronger tidal regime depends on the value of the along-channel density gradient.

To understand the variability of the across-channel residual flow with tidal forcing and water depth, as is presented in Fig. 7, the analytical flow is decomposed into two components (see Eq.13). The components are induced by the residual across-channel density gradient and by Coriolis deflection of the along-channel residual flow, respectively. The top panels of Fig. 11 show that the density-induced component is dominant in the agreement area. The residual across-channel density gradient therefore explains why the transverse residual flow in the agreement area of Fig. 7c increases with water depth.

Physical components of the across-channel residual velocity in the analytical model. The components are forced by the across-channel residual density gradient (left panels) and by Coriolis deflection of the along-channel residual flow. Top panels display the magnitude (largest current in cm s − 1) as a function of tidal strength and water depth. Dashed contours indicate the relative contribution of the components (in %). Bottom panels show the transverse patterns for the default experiment; orientation is looking landward. The density-induced pattern is representative for the agreement area, but the Coriolis-induced component is not (see main text)

The density-induced component features a single clockwise circulation pattern as shown in Fig. 11c in most of the agreement area. The pattern results from residual water density increasing towards the right (solid line in Fig. 3d)). Exception is weak tides in shallow water (U = 0.1 ms − 1 and \(H_{\text{max}}=10\) and 15 m), where the density-induced component is characterized by two counter-rotating circulation cells (not shown). This pattern results from relatively dense water in the channel (dashed line in Fig. 3d). The across-channel residual flow patterns in the agreement area are therefore determined by the across-channel profile of the across-channel residual density gradient.

The Coriolis-induced component features different patterns over the parameter space (e.g, default experiment in Fig. 11d), because of different along-channel residual flow patterns. The patterns are not further discussed here, as the Coriolis-induced component plays a minor role in the agreement range.

3.3.4 Sediment trapping mechanisms

In the agreement area, residual sediment concentrations increase with tidal strength, and sediments are trapped in the fresher water over the left slope of the channel (Fig. 8). These characteristics can be explained as follows. Sediments are eroded from the bed by a bed shear stress and transported laterally by across-channel currents (see the sediment model in Section 2.3). This results in a net advective sediment transport across the channel. The advective transport is balanced by a turbulent diffusive transport laterally, such that sediment distributions are in morphodynamic equilibrium (Eq. 20).

The net advective sediment transport in Eq. 20 consists of a component induced by residual currents, \(T_{\text{M}_0}\), and a component induced by tidal currents, \(T_{\text{M}_2}\). Analysis of numerical and analytical model output in the agreement area reveals that the tidally induced transport is relatively small (at most 20%, not shown). These results are consistent with those of Huijts et al. (2006) and Schramkowski et al. (2010). To understand lateral trapping of sediment, we can therefore focus on transport of the residual sediment concentration by the residual across-channel velocity, \(T_{\text{M}_0}\).

The magnitude of the residual sediment concentration depends on sediment availability and on the residual bed shear stress (Eq. 17). The average sediment availability is fixed in the experiments, such that concentrations mainly vary with the residual bed shear stress. The residual bed shear stress mainly results from the along-channel tidal flow (not shown), explaining why stronger tides induce larger residual sediment concentrations.

In most of the agreement area, the across-channel residual flow feature a clockwise circulation, which mainly results from the residual across-channel density gradient (Section 3.3.3). The clockwise density-induced circulation transports sediment towards the left close to the bed and to the right higher up in the water column. As sediment concentrations increase towards the bed, this results in trapping of sediments in the fresher water over the left slope of the channel.

4 Discussion

4.1 Disagreement areas

To understand why the analytical and numerical model disagree in particular areas, we consider three important assumptions used in the analytical model. Assumed is that (1) tidal currents dominate over residual currents, (2) along-channel currents are much larger than across-channel currents and (3) horizontal density gradients are relatively uniform over the vertical. The first two assumptions require that the ratios \([\bar u]/U\) and V/U are small, where \([\bar u]\) and V represent the order of magnitude of the along-channel residual flow and of the across-channel tidal flow (largest value in a numerical experiment). Analysis revealed that relatively uniform horizontal density gradients were found over the vertical (third assumption) if the bulk Richardson number,

is smaller than 0.25 (representing well-mixed conditions). Here, Δρ is the maximum top-to-bottom density difference in a numerical experiment and H 0 the average depth of the cross-section.

Figure 12 reveals that the flow is tidally dominated over the entire parameter space, except for weak tides in deep water (small Ekman and Stokes numbers). The across-channel tidal velocity is significantly smaller than the along-channel tidal velocity over the entire parameter space. Horizontal density gradients were relatively uniform over the vertical, except for weak tides in deep water (small Ekman and Stokes numbers).

Verification or falsification of analytical model assumptions over the parameter space. Assumed is that: a tidal currents dominate over residual currents, or \([\bar u]/U\ll1\), b along-channel currents are much larger than across-channel currents, or V/U ≪ 1, and c horizontal density gradients are relatively uniform over the vertical, which occurs if the bulk Richardson number Ri ≪ 1 (see main text). Here, \([\bar u]\) and V are the magnitudes (largest numerical currents) of the along-channel residual flow and of the across-channel tidal flow, respectively

The previous section showed that the analytical model was not able to capture the main features of the transverse tidal flow, the transverse residual flow and the residual suspended sediment concentration for small Stokes and Ekman numbers. In this area of the parameter space, two analytical model assumptions are violated: the flow is not tidally dominated and the horizontal density gradients are not relatively uniform over the vertical (Fig. 12). Some of the terms in the shallow water equations (1) that have been neglected by the analytical model might therefore be important here. For example, the local inertia term might be important for the transverse tidal velocity in this area. Vertical differences in the horizontal density gradients affect the transverse distribution of the residual and tidal transverse velocity as well. As the velocity field affects the suspended sediment concentration, differences in the velocity field (in particular the across-channel residual velocity) leads to deviations in the sediment concentration. Note that despite violation of two assumptions, the analytical model was able to reproduce the main features of the along-channel tidal flow and the along-channel residual flow in this area.

The analytical model was not able to reproduce the main features of the numerical along-channel residual flow for strong tides in deep water (Fig. 6). In this regime, the flow is nonlinear (Fig. 2). Advective processes that have been neglected in the analytical model by assuming weakly nonlinear flow may therefore be important. In particular, self-advection of residual along-channel momentum by the transverse residual flow, i.e. \({\bar v}\partial\bar u/\partial y+{\bar w}\partial\bar u/\partial z\), is a potentially important mechanism here (Fig. 13).

Comparison of a self-advection of along-channel residual momentum by the transverse residual flow, \({\bar v}\partial\bar u/\partial y+{\bar w}\partial\bar u/\partial z\), and b net tidal-advection of the along-channel tidal momentum by the transverse tidal flow, \(\overline{{v^\prime}\partial {u^\prime}/\partial y}+\overline{{w^\prime}\partial {u^\prime}/\partial z}\), in m s − 2. The advection components are computed using residual and tidal velocity from the most nonlinear numerical experiment (\(H_\text{max}=60\) m, \(U=1~\text{m~s}^{-1}\)). Orientation is looking landward

Disagreement was also found for the residual suspended sediment concentration for strong tides in shallow water. In the same area, the along-channel residual velocity and the across-channel residual and tidal velocity show some differences as well (e.g. Fig. 7). This is likely caused by a combination of factors. First, the along-channel tidal velocity in the numerical model shows significant overtides, as the incoming tidal wave is distorted because of the strong velocities in shallow water. These overtides not only affect the water motion, but also the sediment concentration through for example a different advection of sediment laterally and an increased erosion of sediment at the bed (the bed shear stress in the analytical model is underestimated by 25%). Second, surface fluctuations are relatively large compared with the water depth, such that the rigid lid approximation used in Eq. 3 may cause deviations. Also, numerical harmonic quantities have to be extrapolated over a large area, which may cause errors in the numerical constituents.

4.2 Density-induced tidal rectification mechanism

The previous section showed that the new density-induced tidal rectified flow component \({\bar u}_\text{rect2}\) is important for the along-channel residual flow in particular conditions. Therefore, the density-induced tidal rectification process is considered here in more details.

The component is forced by net advection of along-channel tidal momentum by the density-induced transverse tidal flow (the advection terms in the residual along-channel momentum equation (10a) with v′ = v ρ ′ and w′ = w ρ ′),

Here, \(F_\text{rect2}\) is the residual force per unit mass. The density-induced tidal rectified flow thus obeys

Boundary conditions are similar to those for the full tidal flow as described in Section 2.1.1. The analytical solution for the density-induced tidal rectified flow is obtained by substituting the analytical expressions for the density-induced transverse tidal flow (see Appendix) in Eq. 27b, integrating the result twice over the vertical coordinate, and using the appropriate boundary conditions. The solution is similar to that for the Coriolis-induced tidal rectified flow in the Electronic supplementary material E.2.4 of Huijts et al. (2009), if subscript ‘rect’ is replaced by ‘rect2’.

The density-induced tidal rectification processes are examined in more detail in Fig. 14. The graphic representations in panel b are introduced first. The representations are similar in the other three upper panels. Panel b shows the along-channel and vertical components of the semi-diurnal tidal velocity at high water slack. Red arrows out of the page (red circles with dot) and blue arrows into the page (blue circles with cross) represent ebb and flood directed currents, respectively. The gray contour line represents zero along-channel tidal velocity. During slack after flood, currents are still flooding in the channel higher up in the water column (see Fig. 4b). Closer to the bed and over the shoals, tidal currents started ebbing. The vertical black arrows symbolize the density-induced vertical tidal currents. During slack after flood, the transverse tidal velocity features two counter-rotating circulation cells as displayed in Fig. 5e. The vertical tidal currents are therefore downward in the channel and upward over the slopes of the channel and over the shoals. Panel b also displays the instantaneous force (per unit of mass) resulting from vertical advection of along-channel tidal momentum by the density-induced tidal flow, \(-w_{\rho}'(\partial u'/\partial z)\), at high water slack. The force is represented by filled arrows into and out of the page. The direction of the force is displayed similarly as the along-channel velocity.

Generation of along-channel residual flow by the tidal rectification processes resulting from advection of along-channel tidal momentum by the density-induced transverse tidal flow. In all panels, orientation is looking landward and blue (red) colours indicate landward (seaward) flow. The top four panels examine the instantaneous force (per unit mass) caused by vertical (a, b) and across-channel advection (d, e) of along-channel tidal momentum during slack tides. Red arrows out of the page (circles with dot) and blue arrows into the page (circles with cross) represent ebb and flood directed currents, respectively. The gray contour line represents zero along-channel tidal velocity. The black arrows symbolize the density-induced across-channel and vertical tidal currents. The density-induced tidal rectification processes intensify or weaken along-channel momentum as indicated by the filled arrows into and out of the page, resulting in the residual force patterns displayed in (c) and (f). Adding these patterns for the default experiment yields the tidally rectified force in g, which results in the along-channel residual flow component shown in h

Panels a–c consider how the density-induced tidal rectification process \(-w_{\rho}'(\partial u'/\partial z)\) intensifies or weakens along-channel momentum (filled arrows into and out of the page). Important are the vertical shear in the along-channel tidal flow (vertical differences in size and direction of the arrows into and out of the page), and the direction of the vertical tidal velocity (direction of the black arrows). During slack after ebb (panel a), ebb-directed currents and down-estuary tidal momentum over the shoals decrease from surface to bed (unfilled blue arrows). The density-induced tidal flow over the shoals is downward (black arrows) and transports a relative excess of down-estuary tidal momentum (filled blue arrows) towards the bed. Therefore, \(-w_{\rho}'(\partial u'/\partial z)\) is an down-estuary force during slack after ebb over the shoals. During slack after flood (panel b), the upward density-induced tidal flow over the shoals (black arrow) transports relatively slow up-estuary tidal momentum to the surface (compare size of unfilled red arrows), resulting again in a down-estuary force (filled blue arrows). The result of the up-estuary forces over the shoals during both slack tides is a residual force \(-\overline{w_{\rho}'(\partial u'/\partial z)}\) over the shoals that is up-estuary as well (panel c). The down-estuary residual force in the deep channel and the up-estuary residual force over the shoals in panel c can be explained in a similar manner. The residual force pattern (panel f) resulting from lateral advection of along-channel momentum by the density-induced tidal flow follows from panels d and e in a similar way. Adding the two forces in panels c and f yields the total residual force that is shown in panel g. The force results in the residual flow pattern displayed in panel h and Fig. 10h.

4.3 Comparison with field data

In this subsection, we briefly compare the results of the new model with these and other available field data, and we discuss the effect of adding tidal variations in lateral density gradients on the skill of the model. The modelled distribution of tidal flow, shown in Fig. 4, agrees with field observations presented in Valle-Levinson et al. (2000), Fugate et al. (2007) and Waterhouse and Valle-Levinson (2010), and references therein. With regard to the transverse tidal flow, it should be noticed that the previous version of the analytical model was not able to show the alternation between a single cell structure during flood and a double cell structure during ebb. The results obtained with the new model and shown in Fig. 5d and e suggest that this feature can be at least partly explained by accounting for tidal variations in the lateral density gradient. Other factors may play a role as well, in particular variations in mixing conditions during the tidal cycle caused by e.g. tidal straining of the density field (see next subsection).

The modelled residual along-channel circulation pattern features, for a considerable range of parameter settings, a dipole structure. Left of the main channel (when looking into the estuary) a band of outward flow occurs, whilst in the channel and towards the right bank a band of weaker inflow occurs. This feature is also visible in the data presented by Valle-Levinson et al. (2000) and Fugate et al. (2007). There are also noticeable differences, one of them being that the observed landward along-channel flows \(\overline{u}\) frequently show a subsurface maximum, whereas the \(\overline{u}\) for the default case in this study attains its maximum at the surface. An explanation is that in some estuaries, wind driven flow and gravitational circulation are important components of the along-channel residual flow, causing a subsurface maximum of landward flow. An example of such a system is presented in Huijts et al. (2009). Also, the distribution of flow will be affected by self-advection processes, relaxing the rigid lid approximation and by using a different formulation for eddy viscosity.

Regarding the transverse residual flow, we note that the modelled patterns are consistent with those shown in Valle-Levinson et al. (2000). To obtain agreement with field data of for example Upper Chesapeake Bay, it would be necessary to account for channel curvature and wind.

Finally, the distribution of tidally averaged density over the Gaussian cross-section, as is computed by the numerical model and used as input in the analytical model, is such that dense water is found in and to the right of the main channel, whereas lighter water occurs near the left bank (when looking into the estuary). Such density distributions are also observed in the field (Valle-Levinson et al. 2000; Fugate et al. 2007) and their physical origin has been discussed in Section 3.3.1.

4.4 Model assumptions and physical consequences

Although this study considers several mechanisms in a range of tidal forcing and water depth conditions, other potentially important mechanisms exist, and other parameters (including settling velocity and estuarine width) may affect the results. This study focuses on relatively straight tidal estuaries with a single channel in the middle, whereas bathymetry may be more complex. In addition, the analytical model presented here does not consider processes like wind forcing and channel curvature, which can be important in natural systems (Li et al. 2008; Kim and Voulgaris 2008).

Another discussion item is that in the set-up of our numerical experiments we have chosen a fixed extent of the intermediate zone, in which the longitudinal density gradient occurs. Moreover, the horizontal eddy diffusivity in this domain is constant and fixed. Consequently, the mean longitudinal density gradient will be only weakly dependent on the tidal flow amplitude U and maximum depth H max of the cross-section. This has been done to investigate the response of the system to two parameters only, thereby keeping the analysis as simple as possible. In our analysis, we consider U and \(H_{\text{max}}\) as independent parameters. At first sight this may seem inconsistent with classic estuarine theory (cf. MacCready and Geyer 2010), which reveals that, for the present formulation of vertical eddy viscosity and eddy diffusivity, the longitudinal salinity gradient scales as \(\rho^{1/3}\,U/H_{\rm max}^{5/3}\). However, a key point of our model approach is that we use our numerical model to generate user-specified values of the along-channel density gradient at the estuarine cross-section that we consider (see Section 2.4). In other words, the location of this cross-section in a real estuary is considered as a free parameter, and so \(\partial\rho/\partial x\), U and \(H_{\text{max}}\) are mutually independent.

The limitation of our work concerns the fact that our analysis has been done for relatively small along-channel density gradients (of order \(1~\times~10^{-4}~\text{kg~m}^{-4}\)) and strong mixing. Such conditions are typical for e.g. the Western Scheldt (Schramkowski and De Swart 2002; Arndt et al. 2007). To obtain a broader insight into the sensitivity of flow and sediment distributions at estuarine cross-sections, similar experiments would be needed for other values of \(\partial\rho/\partial x\) and eddy viscosity A z . For example, in the James River and Hudson typical values of \(\partial\rho/\partial x\) are three to four times larger, and eddy viscosities are about five times smaller than what is considered in this study (Huijts et al. 2006; Scully et al. 2009). The reduction in mixing is due to larger density stratification in such systems. Consequently, results as presented in Fig. 6 would be different. In particular, the border between the weak and the stronger tidal regime will shift towards larger U, as larger \(\partial\rho/\partial x\) and smaller A z result in stronger gravitational circulation.

The present study used an idealized turbulence closure scheme (constant eddy viscosity and diffusion coefficients) and a no-slip condition at the bed. Schramkowski et al. (2010) recently showed that adopting partial slip can have a profound influence on sediment trapping, as it enhances the relative contribution of the tide-induced net lateral sediment transport \(T_{\text{M}_2}\) to the total net lateral transport. Another improvement would be to let A z , K z depend on density stratification, as measured by the bulk Richardson number Ri, defined in Eq. 26. To investigate its consequences on the results, we performed additional numerical experiments in which A z , K z were explicit functions of Ri, following Munk and Anderson (1948). We chose our new formulations in such a way that for our default parameter setting the values for A z and K z remained unchanged. We then run the numerical model for a smaller tidal current (\(U=0.3~\text{ms}^{-1}\)). The results are that A z , K z become smaller, the along-channel tidal flow shows more boundary layer behaviour, the transverse tidal flow is stronger, residual flows increase by about 40%, whereas the structure of the mean sediment concentration is hardly affected. Subsequent runs with the analytical model confirmed the results of the numerical model, and revealed that the decrease in mixing caused larger vertical shears and thus larger transverse velocities and larger tidally rectified flows. The overall skill of the analytical model, as defined by correlation coefficients and magnitude coefficients of the different flow variables and mean sediment concentration, remains high.

More sophisticated turbulence closure schemes (e.g. Burchard et al. 2008, and references herein) would lead to additional flow and sediment transport mechanisms. An example is residual flow driven by strain-induced periodic stratification (Simpson et al. 1990; Stacey et al. 2008; Cheng et al. 2010), and the associated net sediment transport by ebb-flood asymmetries (Jay and Musiak 1994). Other possibly important processes include drying and flooding (Friedrichs and Aubrey 1994), resuspension of sediment by waves (Anderson 1972; Schoellhamer 1995), and flocculation of fine suspended sediment (Winterwerp 2002). These aspects will be addressed in future studies.

5 Conclusions

An analytical and a numerical model were combined to gain understanding of the response of flow and sediment distributions over estuarine cross-sections to changes in tidal forcing and water depth. This was done for estuaries that are characterised by strong mixing and along-channel density gradients of order \(1~\times~10^{-4}~\text{kg~m}^{-4}\). A prototype of such a system is the Western Scheldt. It was also examined in what conditions the fast, two-dimensional (across-channel and vertical) analytical model yields results that agree with those of the more realistic three-dimensional numerical model. The analytical model applies to tide-dominated estuaries with arbitrary across-channel bed profile. Along-channel forcing conditions and bathymetry are assumed to be relatively uniform and the velocity field weakly nonlinear. The model extends a previous analytical model (Huijts et al. 2006) by including tidal variations in the across-channel density gradient. The new forcing induces both transverse tidal flow and (via tidal rectification processes) along-channel residual flow.

Experiments were performed for a range of conditions representing weak to strong tides in shallow to deep estuaries (average tidal velocity amplitude U and maximum water depth \(H_\text{max}\) between 0.1 and 1 m s − 1 and 10 and 60 m, respectively) with a Gaussian shape. The analytical model was able to reproduce and explain important features of the flow and sediment distributions in large parts of the parameter space (agreement areas).