Abstract

Differentiated instruction is considered to be an important teaching quality domain to address the needs of individual students in daily classroom practices. However, little is known about whether differentiated instruction is empirically distinguishable from other teaching quality domains in different national contexts. Additionally, little is known about how the complex skill of differentiated instruction compares with other teaching quality domains across national contexts. To gain empirical insight in differentiated instruction and other related teaching quality domains, cross-cultural comparisons provide valuable insights. In this study, teacher classroom practices of two high-performing educational systems, The Netherlands and South Korea, were observed focusing on differentiated instruction and other related teaching quality domains using an existing observation instrument. Variable-centred and person-centred approaches were applied to analyze the data. The study provides evidence that differentiated instruction can be viewed as a distinct domain of teaching quality in both national contexts, while at the same time being related to other teaching domains. In both countries, differentiated instruction was the most difficult domain of teaching quality. However, differential relationships between teaching quality domains were visible across teacher profiles and across countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Contemporary classrooms throughout the world are filled with students who have varying learning needs because of differences in prior knowledge or readiness, background, and motivation, to name a few. Policies focused on de-tracking, the inclusion of students from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds, and inclusive education have caused the learning needs of students within classrooms to differ considerably. In the same time, policymakers emphasize that all students should be supported to develop their knowledge and skills at their own level (Humphrey et al. 2006; Rock et al. 2008; Smale-Jacobse et al. in press; Tomlinson 2015). One way teachers could address these needs is by using differentiated instruction. Differentiation is a philosophy of teaching, implying that teachers value student diversity and are willing to make adaptations to their teaching to better meet the learning needs of diverse students (Tomlinson et al. 2003). When teachers apply these ideas to adapt the instruction in their lessons, we call it differentiated instruction. Addressing students’ learning needs by teaching adaptively within classrooms, as opposed to stratification between classrooms or schools, has been proposed as a desirable approach in a fair educational system (OECD 2012, 2018b). Within-class differentiated instruction may be implemented by pre-planned adaptations of content, process, product, learning environment, or learning time based on assessment of students’ readiness or another relevant characteristic influencing students’ learning (Tomlinson 2014).

To gain more insight in how differentiated instruction is implemented within classrooms, information from observations can provide us with meaningful information. Classroom observations are often used to understand teaching by identifying ‘dimensions’ of teaching and investigating how those dimensions contribute to outcomes such as student learning or motivation. In time, this can inform initiatives for improving teaching (Bell et al. 2019). Since differentiated instruction has been a topic of interest in different countries across the world, it would be insightful to see how differentiated teaching behaviour is observed in classrooms internationally. International comparisons of teaching between countries could give insights in whether teaching quality can be generalized from one context to another, and unveil whether relationships among teaching behaviours are the same across a full range of school and classroom contexts (Reynolds 2000; Reynolds et al. 2014). Therefore, in this study, we focus on cross-country comparisons of classroom observations of differentiated instruction.

Our study takes the form of an empirical and psychometric analysis of observed differentiation practices in two countries: South Korea and The Netherlands. In these two countries, differentiated instruction has gained prominent interest of educationalists and policymakers (see e.g. Kim, Cho & Lee, 2012; Ministry of Education, Culture and Science 2014, 2016). Both countries are ranked among the above average scoring countries with regard to student performance in popular comparative studies such as the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS), and Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) (Martin et al. 2016a, b; Mullis et al. 2017; OECD 2016d). Teachers in both countries generally see the benefits of differentiated instruction, but struggle with applying it in practice (Cha and Ahn 2014; Van Casteren et al. 2017). Naturally, there could also be differences between these countries that may affect how teachers differentiate, such as cultural values and the practical support teachers receive. Exploring similarities and differences in differentiated teaching across South Korea and The Netherlands may open up doors for learning from each other and further developing initiatives to boost differentiated teaching on a more global scale.

In international studies, the question whether constructs can be measured and interpreted in the same way in both contexts is of great importance (Van de Vijver and Tanzer 2004). Past research investigating teaching quality between The Netherlands and South Korea has provided a useful indication regarding comparability of interpretations (measurement invariance) and the feasibility of comparing teaching quality, including differentiation (Van de Grift et al. 2017). However, this previous study is subject to some limitations. First, the study relied mainly on the variable-centred approach treating the response categories as being continuous. Treating categorical variables as continuous may introduce bias because the distance between categories is assumed to be equal, while in reality this may not be the case. Second, the study included a relatively small sample from the Netherlands, including only experienced teachers. Third, the analysis included a student engagement measure in the simultaneous analysis of factor invariance, while conceptually student engagement is not a component of teachers’ teaching behaviour. In the present study, we aim to replicate these results by using larger samples and refined methodological approaches combining variable-centred and categorical multiple-group confirmatory factor analysis and person-centred (categorical latent class analysis) approaches. Moreover, the current study focuses specifically on differentiated instruction, which gives the possibility of further exploring this specific domain by studying how differentiated instruction is related to other domains of teaching. Because of its importance for practice and policy nowadays, it is helpful to know how differentiated instruction is related to other teaching quality domains and to see whether it is possible to distinguish different types of teachers with regards to their differentiated instruction.

In short, the present study aims to facilitate cross-national comparisons of differentiated instruction by studying how an observation scale measuring differentiated instruction is interpreted across countries, how differentiated instruction relates to other teaching domains and how teachers can be clustered with regards to their differentiated instruction. By doing this for the context of South Korea and The Netherlands with relatively large samples, we set out to extend and refine previous findings with regard to differentiated instruction in these countries.

Theoretical framework

Differentiated instruction

When teachers aim to differentiate their teaching, they may organize this by differentiating their instruction within the classroom or beyond the classroom (e.g. by tracking students between classrooms). Our focus is on differentiated instruction within classrooms. In differentiated instruction in the classroom, the primary focus is on the teaching practices and techniques teachers use and the content, processes or products they differentiate (McQuarrie et al. 2008; Valiande and Koutselini 2009) in respect to the assessment of students’ learning needs (Prast et al. 2015; Roy et al. 2013; Tomlinson 2014). Teachers may for instance adapt the complexity of the task, offer students different learning times, give extended instruction to subgroups of students or allow for variations in students’ output. Secondly, the organizational aspect of differentiated instruction entails the structure in which the differentiated instruction is embedded (for instance in homogeneous or heterogeneous groups) (Smale-Jacobse et al. in press). To enable differentiated instruction during a lesson, teachers should plan the period and lesson, assess students’ learning needs, prepare and execute the differentiated instruction during the lesson, evaluate students’ progress and use other effective teaching behaviours like classroom management and high-quality instruction that set the stage for differentiation (Keuning et al. 2017; Smale-Jacobse et al. in press).

Differentiated instruction has been related to better student outcomes in multiple meta-analyses of the literature, mostly having small to moderate effects (Deunk et al. 2018; Hattie 2009; Kulik et al. 1990; Smale-Jacobse et al. in press; Steenbergen-Hu et al. 2016), although some studies found no or limited empirical evidence for benefits of the approach (Sipe and Curlette 1996; Slavin 1990).

Differentiated instruction as an aspect of teaching quality

In our study, we follow the conceptualization of differentiated instruction as being one of six domains of observable teaching behaviours that together indicate teaching quality: creating a safe learning climate, efficient classroom management, quality of instruction, activating teaching methods, teaching learning strategies and differentiated instruction (Van de Grift 2007). This categorization has been used to operationalize teaching quality in the International Comparative Analysis of Teaching and Learning (ICALT) instrument (Van de Grift 2014). These domains of teaching behaviours used in this instrument have been strongly grounded in the literature on teaching quality, and encompass nearly all teaching domains from other well-known instruments (Bell et al. 2019; Dobbelaer 2019; Van de Grift 2014), including the ones used by Pianta and Hamre (2009) and Danielson (Danielson 2013; see for a comparison Maulana et al. 2015). Additionally, the instrument is economic and user-friendly due to manageable number of items, comprehensible language use and simple format, which makes it highly attractive for researchers and teachers internationally. Moreover, the six-domain framework of teaching quality has been successfully applied in a previous study on comparisons of teaching across South Korea and the Netherlands (Van de Grift et al. 2017), as well as in other cross-national comparisons of teaching (Van de Grift et al. 2014), providing a justification for our stance.

Other well-known teaching quality models also include differentiated instruction into their conceptualizations. For instance, one conceptual framework uses three domains of teaching quality: classroom management, student support (including e.g. differentiation and feedback) and cognitive activation (including e.g. challenging tasks and support of learning strategies; Praetorius, et al. 2018). A recent review of frequently used observation measures for teaching quality identifies nine domains of teaching included in different teaching quality instruments: safe and stimulating learning climate, classroom management, involvement/motivation of students, explanation of subject matter, quality of subject matter representation, cognitive activation, assessment for learning, differentiated instruction, teaching learning and student self-regulation (Bell et al. 2019). Another study in which eleven observation instruments were compared shows that some operationalization of differentiated instruction was included in almost all of the content-generic and hybrid instruments, in combination with items on classroom- and time management, presentation of content, activation of students, teacher support, assessment and socio-emotional support (Praetorius and Charalambous 2018). Regarding the form and quality of the lessons, the domains of teaching typically include different effective teaching behaviours such as setting minimum goals, using clear and structured teaching, activating students, supporting students in the use of learning strategies, providing challenging feedback and support, regularly evaluating students’ learning progress, guiding students’ learning by means of modelling and questioning, providing students with subject-specific learning activities and providing differentiated instruction to meet students’ learning needs (Creemers, Scheerens, & Reynolds 2000; Creemers and Kyriakides 2006; Day et al. 2008; Hattie 2009; Klieme et al. 2009; Ko et al. 2013; Kyriakides et al. 2013; Muijs et al. 2014; Reynolds et al. 2014; Scheerens 2016; Seidel and Shavelson 2007; Van de Grift 2014). Some well-known examples of instruments of teaching quality including items on differentiated are the ISTOF instrument by Teddlie et al. (2006), the COS-R instrument by Van Tassel-Baska et al. (2006), the FFT instrument by Danielson (2013) and the ICALT instrument by Van de Grift et al. (2014). Alternatively, in some models of teaching quality, differentiation is taken up as an integral part of all teaching quality domains (Kyriakides et al. 2009). Based on a large-scale study on teaching quality across European, North-American, Pacific Countries, Canada and Australia, Reynolds et al. (2002) concluded that most factors known from national school- and teacher effectiveness research ‘work’ in different international contexts. However, the way they are operationalized in practice may vary across countries based on the teaching context.

Theoretically, other domains of teaching behaviour such as making sure the learning environment is encouraging for all students and managing classroom routines are expected to facilitate successful execution of differentiated instruction (Tomlinson 2014). Also, high-quality behaviours like explaining or questioning can be used in a differentiated manner, and in that way provide input for differentiated instruction (Smale-Jacobse et al. in press). In line with this theoretical relatedness, empirical studies have found that differentiated instruction was related to—but also empirically distinguishable from—other domains of teaching (Van de Grift et al. 2014, 2017; Van der Lans et al. 2017, 2018). There is evidence that teaching quality can be measured as a unidimensional construct including different domains that build up in a stage-like manner (Pietsch 2010; Van de Grift et al., 2014; Van der Lans et al. 2018).

Complexity of differentiated instruction

From the literature, we know that teachers often find differentiating instruction relatively challenging to implement in practice (Tomlinson et al. 2003; Subban 2006). This can also be traced back to the results of empirical studies on teaching quality. Previously, IRT modelling was used to distinguish the systematic ordering of observed teaching behaviours. In different contexts, a cumulative-hierarchical ordering of teaching behaviours has been found, suggesting that the probability of a teacher to implement differentiated instruction within classrooms increases when other teaching quality domains are better. In that sense, differentiated instruction is related to other domains in a stage-like manner in which differentiated instruction is one of the relatively demanding domains of teaching behaviours that is typically seen in the lessons of highly effective teachers who incorporate behaviours from other domains in their lessons too (Van de Grift et al. 2014, 2017; Pietsch 2010; Van der Lans et al. 2017, 2018). For example, teachers who are good in classroom management, clear explanation and activation of students are more likely to differentiate than teachers who facilitate a good classroom climate but cannot yet explain clearly. Teachers with relatively high teaching quality are more likely to teach in a student-centred manner and take into account student differences into their teaching (Pietsch 2010).

The current study

Study context

Findings from a previous study in the context of South Korea and the Netherlands show some evidence for the possibility to reliably measure differentiated instruction across national contexts and to relate it to other teaching behaviours (Van de Grift et al. 2017). This study shows that South Korean teachers may be more skilled in differentiating instruction than Dutch teachers. However, other studies have found mixed findings for the comparability of differentiated instruction across countries (OECD 2014b; Van de Grift 2014). When studying teaching across countries, the context matters (Van de Vijver and Tanzer 2004). In the following section, a description is given of the national contexts in which our study took place.

The Netherlands

Student performance

International comparisons in secondary and primary education show that students attending Dutch schools perform above average, comparable to other high-performing European and Asian educational systems (Martin et al. 2016a, b; Mullis et al. 2017; OECD 2016d). The majority of teenagers master at least the basic skills in reading, mathematics and science.

School system

The Dutch educational system is highly tracked (i.e. students are separated by ability in a large number of different educational tracks from the early age of twelve), does not apply a national curriculum and gives extensive autonomy to schools and teachers (OECD 2014a, c, d). The high level of decentralization is balanced by a strong school inspection mechanism and a national examination system.

Teaching profession

The teaching profession does not have an above average status, but the quality of teachers is generally high with the large majority mastering the basic teaching skills well (Inspectorate of Education 2018a; Schleicher 2016).

Issues and policies related to differentiated instruction

There are some concerns about the Dutch education system. For instance, the early tracking system creates obstacles for students to switch tracks flexibly. Even in a highly tracked system, teachers need to increase the use of differentiated instruction in order to support students with different learning needs within the tracks, to support permeability between the tracks, and to enhance student motivation (OECD 2016c). Next, there is a concern that excellent students may not be reaching their full potential (Ministry of Education, Culture and Science 2014; OECD 2016c). Moreover, there is a current debate about the limited opportunities of children of low socioeconomic status to compensate for their initial learning delays and perform according to their potential (Inspectorate of Education 2018a). Based on these issues, supporting performance and equity are important issues in Dutch education (OECD 2014a). Such policy trends have increased the demand for differentiated instruction practices with a focus on supporting underperforming students as well as on stimulating talented students (Ministry of Education, Culture and Science 2014, 2016). It is even taken up in national law that schools must align teaching to the learning needs of different students. The implementation of differentiated instruction is supervised by the Inspectorate of Education [Inspectie van het Onderwijs] (2018a, b).

Differentiated instruction in practice

Although Dutch teachers are aware of the general ideas behind differentiated instruction, they find it challenging to fully understand the concept and to appropriately use it in practice (Van Casteren et al. 2017). Nevertheless, differentiated instruction has been implemented to some extent. For instance, ability grouping within some classes is not uncommon (OECD 2016d). And a few years ago, about a quarter of students reported that their mathematics teacher ‘gives different work to students who have difficulties in learning and/or to those who can advance faster’ (Schleicher 2016). However, differentiation is often observed to be rather ad hoc and takes place outside of the classroom frequently. In both secondary and primary education, the implementation of differentiated instruction shows ample room for improvement (Inspectorate of Education [Inspectie van het Onderwijs] 2018a; OECD 2016c). The difficulties Dutch teachers experience seems to stem from issues of practical nature as well as limited professionalization; e.g. they do not receive much training in differentiated instruction and assessment skills, they feel that there is too little time available for developing and planning differentiated lessons and collaboration between colleagues is limited (OECD 2016c; Van Casteren et al. 2017). Furthermore, policy requirements asking teachers to both strive for equity by offering extra support to low-ability students and to promote excellence of top performers may result in dilemmas about how they should best spend their time (Denessen 2017).

South Korea

Student performance

The South Korean educational system is among the top-performing systems showing great improvements over time according to most of the PISA and TIMSS assessments (Martin et al. 2016a, b; OECD 2016e). This remarkable educational development contributed to a boost of human capital and economic growth (Akiba and Han 2007; Bermeo 2014). South Korea’s performance reveals a low percentage of underachieving students, and high percentages of excellent students.

School system

Tracking starts at the age of 14, which is the same as the OECD average, and grade repetition is rare (OECD 2016b). On average, class size is around 23 students (OECD 2018a). In general, in the Korean society, education is seen as top priority, which has deep roots in South Korea’s traditional respect for knowledge and ongoing development (Bermeo 2014). High academic achievement is greatly prized and is closely monitored using the evaluation and assessment framework defined by the Ministry of Education (OECD 2016b). One of the major learning resources in South Korean classes is government endorsed textbooks, and information and communication technology (ICT) is used frequently as well (Bermeo 2014; Heo et al. 2018).

Teaching profession

The South Korean system greatly emphasizes teaching quality and ongoing development in the teaching profession. Teachers are recruited from the top graduates, with strong financial and social incentives (social recognition as well as opportunities for career advancement and beneficial occupational conditions; Heo et al. 2018; Kang and Hong 2008; OECD 2016b; Sami 2013; Schleicher 2016). South Korean teachers participate frequently in after-school professionalization activities and work together relatively much by, for instance, sharing lesson plans, activities and student materials (Sami 2013).

Issues and policies related to differentiated instruction

There are some issues in the South Korean system that have raised the need for differentiated instruction. First, South Korea is experiencing a rapid growth in students from multicultural families, due to rising immigration and an increasing number of international marriages (OECD 2016b). Second, differences between students within classrooms are increasing due to ‘shadow education’ in the form of tutoring in private tutoring institutions called ‘hagwons’ (Byun and Kim 2010). The South Korean government offers supplementary educational material free of charge to all students (Heo et al. 2018; OECD 2016b). However, there is still the need to further develop policies targeted at supporting students from low-income and multicultural households (OECD 2016b). Third, there are concerns about students’ motivation and well-being (Kim 2003; OECD 2017). Since 2003, new policies regarding the ‘7th National Curriculum’ have been implemented to improve student centredness and student autonomy (Kim 2003). These changes are mostly aimed at between-class differentiation. One major initiative to improve differentiation within the classroom is the ‘SMART learning’ initiative from the Korean government. Smart Learning is an acronym for Self-directed, Motivated, Adaptive, Resource-enriched, and Technology-embedded intervention, including possibilities for differentiated instruction fostered by technology (Kim, Cho & Lee, 2012). Additionally, since 2009 the Zero Plan for Below-Basic-Level Pupils has been in place highlighting the focus for low achievers to meet educational standards (Lee 2016). Lastly, the ‘2015 revised subject curriculum’ has strengthened the focus on helping students to acquire a balanced set of subject competencies (Han et al. 2017). Competency-based teaching could provide opportunities for differentiated instruction, although this is not explicitly addressed in this respect.

Differentiated instruction in practice

Some studies report that South Korean teachers do acknowledge the need to differentiate in the classroom. In other studies, Korean teaching has been marked as relatively traditional and with little emphasis on differentiation (Lee 2016; Shin 2012). Just like Dutch teachers, teachers in Korea struggle with implementing differentiated instruction in practice (Cha and Ahn 2014). For instance, only about 16% of students in the PISA study of 2012 reported that their mathematics teacher gave ‘different work to students who have difficulties learning and/or to those who can advance faster’ (Schleicher 2016). However, policies like SMART education may open up more possibilities for differentiation in practice, and have already been implemented to some extent (Kim, Cho & Lee 2012). Also, publishers often provide supplementary materials for different levels that could be used to differentiate (e.g. for mathematics, Kim et al. 2013). Some issues teachers may have with differentiated instruction are for instance that they have to balance the quest for differentiated instruction with the very strong pressure to achieve excellence (in terms of high test results) from students and parents, which poses a serious challenge for them (Cha and Ahn 2014). In addition, the highly standardized national curriculum offers relatively limited autonomy for teachers (Schleicher 2016). Teachers do have some freedom to adapt learning content and instruction, but in general, Korean teachers follow the textbooks quite strictly (Heo et al. 2018). Lastly, given the Confucian cultural tradition of valuing groups over individuals, teachers may encounter resistance from students and parents who might be reluctant to acknowledge their differences.

To sum up, it is apparent that in both educational systems, teachers in general are competent, and students’ academic performance level is high. Nevertheless, teachers in both countries struggle to implement differentiated instruction, because of both practical reasons (both countries) and balancing cultural values (particularly Korea). To some extent, differentiated instruction has already been implemented into both educational systems (by means of e.g. ability grouping and SMART learning). Differentiated instruction is promoted at the policy level with the aim to address both concerns about equality of educational opportunities and about promoting excellence. One step forward to support differentiated instruction in both countries is to test the usefulness and relevance of an instrument measuring differentiated instruction and its correlates to enable cross-country comparisons.

Aims and research questions

The current study aims to investigate the factor structure of a differentiated instruction scale for classroom observation in comparison to other teaching quality domains, in order to gain empirical evidence regarding the relevance and adequacy of comparing differentiated instruction and its correlates across countries. Two complementary approaches to test the cross-national comparability (measurement invariance) of the differentiated instruction observation measure and its correlates were applied: (1) a variable-centred approach suitable to test the comparability of country average scores, and (2) a person-centred approach suitable to test the comparability of similar groups of teachers with similar scoring patterns in the two countries. Person-centred approaches may produce multiple sets of parameters, while variable-centred approaches produce a single set of group parameter (Howard and Hoffman 2018). Compared with variable-centred approaches, the results of person-centred approaches ‘provide a moderate amount of specificity, as multiple subpopulations are described separately rather than the entire sample together; and they provide a moderate amount of parsimony, as multiple sets of parameters are produced rather than only one’ (Howard and Hoffman 2018, p. 850).

To address this central aim, the research questions are specified as follows:

-

1.

Is differentiated instruction empirically distinguishable from other domains of teaching quality in both countries? (construct specificity)

-

2.

Is differentiated instruction interpreted identically in both countries? (variable-centred measurement invariance)

-

3.

How does differentiated instruction relate to other domains of teaching quality in both countries? (correlates)

-

4.

Are there differential relationships between differentiated instruction and other domains of teaching quality in both countries? (differential effect)

-

5.

Are different patterns of teaching quality identified from a simultaneous analysis of teacher practices equivalent across the two countries? (person-centred measurement invariance)

-

6.

Is there evidence to support that differentiated instruction is shown to be the most demanding domain compared with other teaching quality domains in both countries? (complexity level)

Methods

Participants and procedure

The present study included secondary school teachers in The Netherlands (Nteachers = 609, Nschools = 160) and in South Korea (Nteachers = 376, Nschools = 26) respectively. Of the Dutch teachers in the sample, 22.1% taught science-related subjects, 58.6% were female and 62.4% were inexperienced. The average class size was 22.33 (SD = 9.45). Of the South Korean teachers, 34.3% taught science-related subjects, 51.3% were female and 30.9% were inexperienced. The average class size was 29.12 (SD = 7.15).

In both countries, similar procedures were applied. Initially, a stratified random sampling was used. Due to low response rates, however, convenience sampling was applied. Invitations to participate followed the common practice in each country. In the Netherlands, schools were invited directly to participate by the principal researchers. In South Korea, schools were invited through the formal educational district office. All teachers participated on a voluntary basis, after an agreement was made between researchers and the participating schools. The participating teachers from The Netherlands came from 12 out of 25 educational regions of the Dutch education system. The participating South Korean teachers were from three provinces (Daejon, Chungbuk and Chungnam) that are among the total 17 local educational authorities, which represent the average characteristics of schools and lessons in the country.

Typical lessons of the participating teachers were observed in the natural setting by trained national observers during the academic year of 2017. Observers observed a full lesson. In South Korea, one lesson was 45 minutes in junior secondary education and 50 minutes in senior secondary education. In The Netherlands, one lesson was 50 minutes in secondary education. The lesson of each participating teacher was observed once.

Measure

An observation instrument called the International Comparative Analysis of Teaching and Learning (ICALT, Van de Grift, et al. 2014) was applied to observe teaching quality, including differentiated instruction. The instrument is organized into six domains of teaching quality captured by 32 items: safe and stimulating learning climate (4 items), efficient classroom management (4 items), clarity of instructions (7 items), intensive and activating teaching (7 items), differentiated instruction (4 items), and teaching learning strategies (6 items). Items were rated on a 4-point Likert scale: ‘1 = mostly weak’, ‘2 = more often weak than strong’, ‘3 = more often strong than weak’ and, ‘4 = mostly strong’.

Differentiated instruction includes items referring to teacher behaviour such as ‘[the teacher] offers weaker learners extra study and instruction time’ and ‘[the teacher] adjusts instructions to relevant inter-learner differences’ (see Appendix A for a listing and descriptive statistics of all items of teaching behaviour, and Appendix B for particular items (high-inference structures) measuring differentiated instruction and the corresponding examples of good practices (low-inference structures)). Each item was rated on a 4-point Likert scale with the following categories: ‘1 = mostly weak/missing’, ‘2 = more often weak than strong’, ‘3 = more often strong than weak’ and ‘4 = mostly strong’. In both countries, the scale reliability is good: between 0.74 and 0.87 (Netherlands), and between 0.79 and 0.87 (South Korea). For the analysis reported here, response categories were recoded into three categories: ‘1 = mostly weak and more often weak than strong’, ‘2 = more often strong than weak’ and ‘3 = mostly strong’. This was done due to low response rates on the first category (‘mostly weak’) on a large proportion of items in both countries. In about 40% of the total items, only 5% were scored mostly weak (in some items, a score 1 was as low as 0.3%). Recoding improved model identification and fit in both sets of analyses (Wang and Wang 2012).

Observer training

In both countries, observers were trained extensively using the same training format and standards. Only observers that were certified in the training were allowed to observe teachers’ teaching practices in the classroom. All observers were experienced teachers knowledgeable about effective classroom practices. The training was organized in two phases. In the first phase, an introduction to the roots and the theoretical foundations of the instrument was provided. The observation guidelines were intensively discussed, and existing misapprehension of contents and constructs were clarified. In the second phase, the observation instrument was applied and practiced by using two different video recordings of teaching behaviours in the classroom until consensus of at least 0.70 across the whole observation instrument was reached. The differences in scores were discussed in detail adding to the clarification of the concepts and observation difficulties. In addition, the consensus estimate between the observers and the expert norm scores was calculated.

We used consensus estimates of inter-rater reliability. Consensus estimates are ‘useful when different levels of the rating scale are assumed to represent a linear continuum of the construct, but are ordinal in nature (i.e., Likert scale) (Stemler 2004)’. The ICALT observation instrument used in this study has those characteristics. We applied a popular method for computing a consensus estimate of inter-rater reliability by using a simple agreement percentage: a product of adding up the number of items that received identical ratings by all raters and dividing that number by the total number of items rated by all raters (Stemler 2004). The percentage of agreement (consensus estimates) from the observer training was between 0.70 (first video) and 0.86 (second video), indicating a satisfactory level of consensus estimates of inter-rater reliability between observers. The consensus estimate between the observers and the expert norm ranged from 0.71 to 0.86, indicating a satisfactory level of inter-rater reliability.

Data analyses

We combined the variable-centred approach using categorical confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and the person-centred approach using categorical latent class analysis (LCA). Combining both approaches is beneficial because both approaches provide complementary, but uniquely informative, perspectives to measurement invariance (Gillet et al. 2019). Specifically, ‘Variable-centered analyses operate under the assumption that all participants are drawn from a single population for which a single set of “average” parameters can be estimated. Person-centered analyses explicitly relax this assumption by considering the possibility that the sample might include multiple subpopulations characterized by different sets of parameters’ (Gillet et al. 2019, p. 241). To answer the first research question, categorical CFA models of teaching quality with the six correlated factors were conducted separately for each country sample. The six-factor solution was compared with the competing one-factor solution where all items loaded on only one factor.

To answer research questions 2–4, measurement invariance testing using the categorical multiple-group CFA (MGCFA) was conducted. The six-factor model was estimated simultaneously for the two country samples. Three competing models were tested including configural, metric and scalar invariance. The configural invariance model tests whether the six teaching quality domains and the set of items associated with each domain have a similar factor structure across countries. The metric invariance model tests whether the factors have the same meaning and the same measurement unit in both countries by assuming that factor loadings are the same in both groups. At the scalar invariance, factor loadings (estimating the meaning of the constructs) and item thresholds (the levels of the categorical items) are assumed to be equal in both countries. Reaching this level of measurement invariance allows for valid cross-country comparisons of factor scores (scale means). Subsequently, mean scores and the corresponding standard deviations of the six teaching quality domains could be estimated.

To answer the remaining research questions (5, 6), multiple-group LCA (MGLCA) was applied to the 32 items. In contrast to factor analysis (in which the aim is to identify interrelated items that describe a continuous latent variable), latent class analysis is a person-centred approach used to identify groups of individuals (categorical latent variable) based on similarities in their item scores and estimate the conditional response probabilities for each item and latent class (Magidson and Vermunt 2004). The LCA approach ‘aims to identify groups with as little variation within a group and as much variation between groups as is possible based on the number of groups that are defined’ (McMullen et al. 2018, p. 73). Groups of teachers can differ on some dimensions (e.g., teaching experience, gender, subject taught), but ‘if similarities can be observed in international comparisons despite those factors, one may argue that there is a relative level of universality’ (McMullen et al. 2018, p. 72) in the groups identified by this analysis.

An initial step in assessing measurement invariance in this framework involves establishing the optimal number of latent classes in each country (Collins and Lanza 2010). Therefore, a series of models with increasing numbers of class solutions (varying between one and five for this analysis) were fitted to the data in each of the two samples as well as on the full merged dataset. The best-fitting class solution was selected and tested in the subsequent measurement invariance analysis.

Furthermore, measurement invariance was tested with a multiple-group LCA analysis where a series of increasingly restricted models estimated simultaneously in all groups were compared (Bialowolski 2016; Kankaras et al. 2011; Magidson and Vermunt 2004). The unrestricted or completely heterogeneous model assumes that the only similarity between countries is the number of classes identified and allows that response patterns (conditional probabilities) and class sizes vary among countries. Although the number of classes in both countries may be the same, direct between-country comparisons is not permitted in this step because the meaning of latent classes may be substantially different. The partially homogeneous model addresses this issue and restricts the measurement part of the model (conditional probabilities) to be equal in both country samples. For each country, the meaning of latent classes is invariant of the country and cross-country comparisons in this respect are meaningful. However, the size of the classes (i.e. the relative importance of each class) may still vary. The completely homogeneous model further restricts the probabilities of class membership to be equal in both country samples (i.e. the percentage of individuals assigned to different classes will be equal in both samples). This last assumption implies that the identified groups of teachers with similar scoring patterns are identical in the two country samples with identical numbers of teachers assigned to each group. Meeting this last assumption ensures the highest level of cross-country comparability, but is difficult to achieve in cross-national studies measuring teaching quality such as the current study.

The common model-data goodness-of-fit indices for the categorical CFA and MGCFA models include the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), the comparative fit index (CFI), and the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), and adhere to common guidelines (i.e., CFI and RMSEA & lower and upper for 90% confidence interval of RMSEA <0.08; CFI >0.90; TLI >0.90) for an acceptable model fit (Brown 2014; Desa 2016; Wang and Wang 2012). In addition, to evaluate competing models, changes in CFI (ΔCFI), TLI (ΔTLI) and RMSEA (ΔRMSEA) of < 0.01 were applied (Cheung & Rensvold, 2012; Desa 2016; Wang and Wang 2012). For MGLCA, the most commonly used goodness-of-fit indices were applied, as well as the Bayesian information criterion (BIC). Smaller values of the BIC indicate better model fit, suggesting that the model with the lowest value characterizes the most representation of the data. To assess the quality of class membership classifications, the entropy criterion information was used. The values of the entropy criterion range from 0.0 to 1.0, with values closer to 1.0 indicating a better classification (Muthén and Muthén 2007). Entropy values above 0.6 are considered sufficient. All analyses were conducted using a statistical program Mplus version 7.4 (Muthén & Muthén, 2018).

Results

The reliability of the differentiated instruction scale (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.78) and other teaching quality scales are good (Cronbach’s alpha > 0.70). The six-factor CFA models indicate a better fit for the competing one-factor model (see Table 1, upper part). The fit indices of the six-factor model of teaching quality is satisfactory, with CFIs = 0.93 and 0.97, TLIs = 0.92 and 0.96 and RMSEAs = 0.06 and 0.006 for Dutch and South Korean samples, respectively. Factor loadings derived from CFA results for both samples indicate that all items load sufficiently (> 0.60) on the corresponding domains. Particularly, items measuring differentiated instruction have high factor loadings in both country data, ranging from 0.73 to 0.87 (see Table 2). These results suggest that the hypothesized six domains of teaching behaviour, which distinguishes differentiated instruction from other teaching quality domains, is confirmed for both Dutch and South Korean samples. This means that differentiated instruction is empirically distinguishable from the other domains of teaching quality in each country (research question 1).

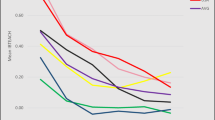

The latent factor structure of teaching quality is similar across the two national samples (see Table 1, lower part), as indicated by good indices at the configural, metric and scalar levels of invariance (CFIs and TLIs > 0.90, RMSEAs < 0.08) as well as by the comparative assessments of relative fit indices (ΔRMSEAs, ΔCFIs, ΔTLIs < 0.01). This confirms that all domains of teaching quality are invariant, and interpreted and responded to in a similar manner in both countries. This indicates that differentiated instruction (and also the other five domains of teaching behaviour) in the two national samples can be compared on latent mean scores (research question 2). The results in Table 3 show that differentiated instruction was observed more frequently in South Korean teachers’ classrooms compared with Dutch teachers (p < 0.01). To give general information about differentiated instruction in comparison to other domains, mean scores and the corresponding standard deviations of the six teaching quality domains are presented (see Table 4).

Furthermore, results show that differentiated instruction is significantly and positively related to other domains of teaching behaviour, and this applies to both national contexts (see Table 5). Higher performance in differentiated instruction is associated with higher performance in other domains of teaching behaviour, and vice versa (research question 3). In both countries, the activating teaching domain appears to be the strongest correlate of differentiated instruction, followed by teaching learning strategies, clarity of instruction, classroom management and learning climate.

Results also reveal differential relationships between differentiated instruction and other domains of teaching quality in both countries (see Table 5). Compared with the Netherlands, the relationships between differentiated instruction and the other domains of teaching quality in South Korea are considerably stronger (research question 4).

Moreover, MGLCA results show that the partially homogeneous model seems to be the best model representing the data compared with the completely heterogeneous and completely homogeneous models, as indicated by the BIC index (see Table 6, lower-right part, M2) and by the high entropy value of 0.95. This means that in both national contexts, four comparable types (classes) of teachers in terms of the patterns of their teaching quality can be identified. These four types describe similar scoring patterns of teaching behaviour, but the relative number of teachers assigned to these groups varies across both national contexts. This result confirms that the determined profiles are sufficiently equivalent across the two countries (research question 5).

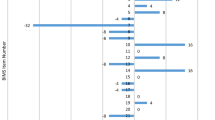

The four classes were labelled further as groups A, B, C and D (see Fig. 1). In the Dutch sample, groups A and B consisted of a relatively small number of teachers (NA,NL = 78; NB,NL = 69). Group C was the largest (NC,NL = 287) and accounted for almost 50% of the entire sample, while Group D contained 28% of the sample (ND,NL = 172). In the Korean sample, groups A, B and D contained roughly 30% of the sample each (NA,KOR = 105; NB,KOR = 119; ND,KOR = 112). Group C was the smallest with only 10% of the sample (NC,KOR = 37).

The visual representation of conditional probabilities of the four classes/groups shows that teaching quality domains appear to be ordered in terms of level of complexity (see Fig. 1). In all four classes/groups, differentiated instruction is shown to be the most demanding domain compared with other teaching quality domains. This pattern applies to both national samples (research question 6).

Further inspection of patterns in the four classes/groups indicates that group A is characterized by teachers who are good in all domains of teaching behaviour. In contrast, group D is marked by teachers who are weak in all domains of teaching behaviour. Furthermore, teachers in group A and B share similar characteristics in their mastery of teaching behaviour. Both groups appear to be weak in the more demanding teaching quality domains. Particularly, both groups do not master differentiated instruction, while group C seems to struggle with teaching learning strategies in their classrooms as well.

Conclusions and discussion

The current study aims to add to the body of knowledge regarding the adequacy of comparing differentiated instruction practices across countries by examining the factor structure of differentiated instruction in comparison to other teaching quality domains.

Using the categorical CFA framework, differentiated instruction can be distinguished empirically from other domains of teaching behaviour. Hence, our study supports the theoretical idea that differentiated instruction is a specific construct that can be viewed as a distinct domain of teaching quality (Van de Grift 2007). The construct specificity of differentiated instruction is empirically evident in both Dutch and South Korean samples. The two national contexts represent two diverse cultures and educational systems. Hence, our findings add to the ecological validity of the differentiated instruction operationalization specifically, and teaching quality constructs more generally. Also, from the variable-centred approach of measurement invariance using the categorical MGCFA framework, evidence indicates that the differentiated instruction construct is interpreted in a similar way in The Netherlands and South Korea. This suggests that the differentiated instruction construct, though conceptually complex (Smale-Jacobse et al. in press), appears to be a relevant construct in the two diverse cultural settings.

Differentiated instruction appeared to be observed more frequently in South Korea compared with The Netherlands, confirming results of past research (Van de Grift et. al 2017). Reasons for this finding are not straightforward. As discussed earlier, South Korean teachers seem to struggle with differentiated instruction, just as their Dutch colleagues. Indeed, both scores show room for improvement. However, apparently, there are context-specific factors that may explain why in South Korea differentiated instruction was observed more than in The Netherlands. One possible explanation may be found in the quality of teacher professionalization in South Korea. In general, South Korean teachers engage in ongoing professionalization frequently (Heo et al. 2018; Sami 2013) and they experience relatively much support from peer networks (Schleicher 2016) which may help them in the development of their teaching. Conversely, teachers in The Netherlands experience relatively little support from school leaders and peers when it comes to differentiated instruction (Van Casteren, 2017). South Korea has a very high-quality and competitive licensing assessment for secondary school teachers (National Center on Education and the Economy 2018). Teacher salaries increase along with increasing quality of teaching, time spent on guiding students and continuous professional development (Choi and Park 2016) which could provide an incentive for implementing high-quality teaching behaviours such as differentiated instruction. In South Korea, technology is often used in classrooms (Bermeo 2014; Heo et al. 2018), and initiatives like SMART learning have opened up possibilities for better accommodating students’ learning needs by means of ICT (Kim, Cho & Lee 2016). In Dutch education, most teachers use ICT too, but specifically using applications to facilitate extra practice, for instance, is less common (Kennisnet 2017). Dutch teachers have relatively little planning time and may perceive their classrooms as relatively homogeneous due to the existence of external forms of differentiation and (ability) tracking in secondary education, which may (in part) explain why they differentiate less (Van Casteren et al., 2017). Additionally, government initiatives in Korea like the ‘Zero Plan’ may affect differentiated instruction, although in Dutch education, there are government incentives to support low-achieving students and talented students too (Ministry of Education, Culture and Science 2014, 2016). Lastly, a major learning resource in Korean classes is government-endorsed textbooks, and workbooks (Heo et al. 2018). The quality of these materials may also have added to our findings. More in-depth research would be needed to unravel the content and sources used in differentiated instruction across the countries to add to our understanding of differences between countries. In addition, future research can benefit from adding important personal and contextual factors that may explain differences in differentiated instruction in both countries. Our findings on differences between countries are a first step in comparing differentiated instruction across contexts. Combining such quantitative findings about the quality of differentiated instruction with more in-depth descriptions of best practices in differentiated teaching could provide practically relevant input for teachers across countries to learn from one another.

Concerning the relationship of differentiated instruction and other teaching domains, results showed that learning climate, classroom management, clarity of instruction, activating learning and teaching learning strategies are correlates of differentiated instruction in both countries. Higher performance in differentiated instruction is linked to higher performance in the mentioned domains of teaching quality, and vice versa. This suggests that teachers practicing differentiated instruction are likely to master and apply other domains of teaching quality in their classroom practices. This finding is consistent with the findings of prior studies in the Dutch context showing the interrelationship between differentiated instruction and other domains of teaching quality (Maulana et. al 2015; Van de Grift et al., 2014; Van der Lans et al. 2017, 2018), and extends the evidence beyond the Dutch context in secondary education. Our findings show that activating learning and teaching learning strategies are the two strongest correlates of differentiated instruction in both countries. This suggests that teachers’ differentiated instruction practices are connected to taking an active and stimulating approach to students’ learning, as well as promoting learning strategies for more active and independent learning, which is in line with the student-centred focus of the construct (Tomlinson 2014). Cognitive activation of students has theoretically and empirically been related to student achievement and student interest and also to approaches to teaching matching the premises of differentiated instruction such as student-centred teaching and using formative assessment (Echazarra et al. 2016; Klieme et al. 2009; Praetorius et al. 2018). Additionally, a cognitive analysis of teaching behaviours of expert teachers shows that teachers who differentiate tend to stimulate students to participate in regulation of the learning process (Keuning et al. 2017), which may explain the relatively strong relation between learning strategies and differentiation. Moreover, activating teaching, teaching learning strategies and differentiation have all been found to be relatively demanding compared with other teaching behaviours (Van der Lans et al. 2018). The relationship between differentiated instruction and the other five domains of teaching quality in South Korea is stronger compared with the Netherlands. This suggests that good practices of learning climate, classroom management, clarity of instruction, activating learning and teaching learning strategy are beneficial for differentiated instruction in both countries, and vice versa.

By applying a person-centred approach of measurement invariance using the MGLCA framework, four comparable teacher profiles in both countries were found, which differ in the proportion of teachers assigned to each group in both samples. These profiles represent a group of teachers with high teaching quality including a high level of differentiated instruction (group A), a group with low teaching quality profile including a low level of differentiated instruction (group D) and two groups in which teachers have a reasonably good level of basic teaching skills (i.e. learning climate, classroom management, clarity of instruction), but struggle with mastering the more demanding domains such as differentiated instruction (group B) as well as teaching learning strategies (group C). This finding provides a further confirmation regarding the measurement invariance of differentiated instruction and the five related teaching quality domains that was established using the variable-centred approach. Hence, the person-centred approach is useful not only for measurement invariance testing but also for identifying groups of teachers that vary in their quality of instruction. This could help to develop and apply tailored group interventions. Furthermore, results also show that differentiated instruction appears to be the most demanding domain of teaching behaviour, and this applies to both countries. The results indicate a clear pattern of teaching domains ordered in terms of level of difficulty. Past studies with Dutch pre-service teachers (Maulana et al. 2015) and Dutch experienced teachers (Van der Lans et al. 2017) applying item response theory techniques are consistent with the current study, indicating that differentiated instruction appears to be relatively difficult to master. The MGLCA approach appears to be a potential technique for testing the complexity levels of teaching behaviour, which complements other techniques such as item response theory (Rasch modelling).

To conclude, more proficient teachers might exhibit more connected behavioural domains in comparison to less effective teachers. This might be reflected at a national level, too. Differentiated instruction appears to be the most difficult domain of teaching behaviours in both national contexts. Because differentiated instruction is strongly linked to other five teaching quality domains, this implies that studying and supporting differentiated instruction should be done in connection to other teaching quality domains. The most challenging of all might be the fine-tuning of teaching quality in the different domains into a coherent whole adding to more effective classroom practices.

Limitations

The current study has strengths as regards measuring actual differentiated instruction and the associated teaching quality domains using an objective observation instrument, employing a robust theoretical framework, focusing on secondary education across two countries where scarce studies are available and using relatively novel and complementary methodological approaches. However, there are also some limitations.

Although the data from both countries are sufficiently large and relatively representative, teachers participated on a voluntary basis. This means that the current sample may not include specific groups of teachers which should be included for making inferences at the country level. Hence, caution against the generalization of findings to the country level is warranted until replication studies with broader and more representative sample are available.

Furthermore, the observation instrument used in this study does not capture all aspects of differentiated instruction. The concept was captured using a few specific items and relating these to other teaching quality domains. This overarching approach increased the breadth of the instrument, but diminishes the depth of the measurement of the respective domains, including differentiated instruction. The focus in the observation instrument was on convergent differentiation (aimed at supporting weaker students) and on differentiation of instructions and processing. Other forms of differentiated instruction such as differentiation of learning materials, end product and learning environment are underrepresented. Future refinement of the instrument could help to capture a more comprehensive operationalization of differentiated instruction.

Although the current study applied a sophisticated and advance multigroup CFA and multigroup LCA, the nested structure of the data was not fully taken into account. The convenience sampling procedure resulted in imbalanced teacher-school data, which also varied between countries. In addition, applying a multilevel structure in the categorical CFA and LCA approaches is very complex. Because of the highly expensive costs and demanding nature of natural classroom observations in both countries, it was not possible to collect data from a random sample using a balance sample principle for all nested levels. Future research should attempt to employ a better sampling procedure and employ multilevel CFA and multilevel LCA, if possible, to increase the accuracy of the estimates (Pornprasertmanit et al. 2014). In addition, the current study did not take covariates into account in the multigroup LCA analyses. This choice is justified because the aim is to provide the first attempt regarding clusters at the country level as a person-centred approach of measurement invariance. One may argue that groups of teachers may differ on some characteristics (e.g. gender, teaching experience) which may affect grouping results. Future research aiming at examining more detailed investigation of latent profiles across countries beyond the measurement invariance test will benefit from taking important covariates into account. In addition to frequentist approach of latent class analysis, the Bayesian framework may also be used to gain more insights into differentiated instruction profiles across countries.

Finally, the use of a single measure can also be a limitation for tapping differentiated instruction more comprehensively. Triangulating different sources of information from different stakeholders (e.g. students, teachers, principals) may enrich the understanding of differentiated instruction practices more. Although observation is considered as more objective compared with teacher and student reports (Van de Grift et. al 2017), there could possibly be differences due to the ‘cultural lens’ of observers (compare Aldridge and Fraser 2000). More insight into how teaching quality is understood across national contexts is needed to corroborate findings of the present study. This could for instance be achieved by adding qualitative information and student-level measures in future research.

Implications and future directions

Strong policy support for differentiated instruction and high-quality teaching behaviours is gaining more momentum in international efforts to promote excellence and equal opportunities in education. Yet, comparative research on the topic is still in an incipient stage. Studying differentiated instruction in a comparative context offers the possibility for understanding mechanisms supporting its successful practices which can potentially be translated and adopted (with proper adaptation) across cultural contexts.

The observation measure used in this study is proven to be a valid and reliable tool for tapping actual differentiated instruction practices in both countries, specifically targeted at aspects of content, process, assessment and commonly practiced convergent differentiation. Hence, the measure provides unique information regarding specific areas of improvement and can be used as a diagnostic tool to improve differentiated instruction practices. The measure might potentially be useful for other countries beyond South Korea and The Netherlands as well.

Furthermore, the finding that differentiated instruction appeared to be the most difficult skill to master in both countries implies that schools and educational researchers should pay even more attention to this aspect of teaching behaviour. Because other domains of teaching quality are significant correlates of differentiated instruction, and the six domains of teaching quality follow a systematic order of complexity level, efforts to improve differentiated instruction skills should take into account the other five domains of teaching quality following the notion of zone of proximal development. This can be done by guiding and coaching teachers using the current instrument focusing on domains they are still struggling with step by step towards the differentiated instruction domain.

The current study offers valuable information for future country comparisons and improvement efforts in differentiated instruction and its correlates. Future research will benefit from moving beyond the investigation of measurement properties and taking into account universally relevant and context-specific malleable factors supporting differentiated instruction and its impact on various student outcomes. Studies from the American context indicate that factors such as essentialist curriculum influences, orchestrated teaching materials, high-stakes assessments and reward systems for teachers favouring compliance hinder teachers to practice differentiated instruction (Olsen and Sexton 2009), while fewer restrictive prescriptions to teaching (content) facilitates differentiated instruction (Hoffman and Duffy 2016). In future country comparisons on differentiated instruction, the mentioned hindering and facilitators should be taken into account to confirm their relevance in different cultural contexts.

References

Akiba, M., & Han, S. (2007). Academic differentiation, school achievement and school violence in the USA and South Korea. Compare: A Journal of Comparative Education, 37(2), 201–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057920601165561.

Aldridge, J., & Fraser, B. (2000). A cross-cultural study of classroom learning environments in Australia and Taiwan. Learning Environments Research, 3(2), 101–134. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026599727439.

Bell, C. A., Dobbelaer, M. J., Klette, K., & Visscher, A. (2019). Qualities of classroom observation systems. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 30(1), 3–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2018.1539014.

Bermeo, E. (2014). South Korea’s successful education system: lessons and policy implications for Peru. Korean Social Science Journal, 41(2), 135–151. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40483-014-0019-0.

Bialowolski, P. (2016). The influence of negative response style on survey-based household inflation expectations. Quality and Quantity, 50(2), 509–528. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-015-0161-9.

Brown, T. A. (2014). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. Methodology in the Social Sciences. London: Guilford.

Byun, S., & Kim, K. (2010). Educational inequality in South Korea: The widening socioeconomic gap in student achievement. Globalization, changing demographics, and educational challenges in east Asia (pp. 155-182). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1479-3539(2010)0000017008.

Cha, H. J., & Ahn, M. L. (2014). Development of design guidelines for tools to promote differentiated instruction in classroom teaching. Asia Pacific Education Review, 15, 511–523. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-014-9337-6.

Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2012). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling: A multidisciplinary journal, 9, 233–255.

Choi, H. J., & Park, J.-H. (2016). An analysis of critical issues in Korean teacher evaluation systems. CEPS Journal, 6, 151–171.

Collins, L. M., & Lanza, S. T. (2010). Multiple-group latent transition analysis and latent transition analysis with covariates. Latent Class and Latent Transition Analysis, 41, 225–265. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470567333.ch8.

Creemers, B. P. M., & Kyriakides, L. (2006). Critical analysis of the current approaches to modelling educational effectiveness: the importance of establishing a dynamic model. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 17(3), 347–366. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243450600697242.

Danielson, C. (2013). The framework for teaching: evaluation instrument. Princeton, NJ: The Danielson Group.

Day, C., Sammons, P., Kington, A., & Regan, E. K. (2008). Effective classroom practice (ECP): a mixed method study of influences and outcomes. Swindon: ESRC.

Denessen, E. J. P. G. (2017). Verantwoord omgaan met verschillen: Social-culturele achtergronden en differentiatie in het onderwijs. [Soundly dealing with differences: Social cultural background and differentiation in education]. (Inaugural lecture). Leiden, the Netherlands: Leiden University. Retrieved from Retrieved from https://openaccess.leidenuniv.nl/handle/1887/51574.

Desa, D. (2016). Understanding non-linear modeling of measurement invariance in heterogeneous populations. Advances in Data Analysis and Classification, 1-25. https://doi.org/10.1007/SII634-016-0240-3.

Deunk, M. I., Smale-Jacobse, A. E., de Boer, H., Doolaard, S., & Bosker, R. J. (2018). Effective differentiation practices: a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies on the cognitive effects of differentiation practices in primary education. Educational Research Review, 24, 31–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2018.02.002.

Dobbelaer, M. J. (2019). The quality and qualities of classroom observation systems. Enschede: Ipskamp Printing. https://doi.org/10.3990/1.9789036547161.

Echazarra, A., Salinas, D., Méndez, I., Denis, V. & Rech, G. (2016). How teachers teach and students learn: successful strategies for school. OECD Education Working Paper No. 130. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Retrived from: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/how-teachers-teach-and-students-learn_5jm29kpt0xxx-en.

Gillet, N., Caesens, G., Morin, A. J. S., & Stinglhamber, F. (2019). Complementary variable- and person-centered approaches to the dimensionality of work engagement: a longitudinal investigation. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 28, 239–258. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2019.1575364.

Han, H. C., et al. (2017). Issues and implementation of the 2015 revised curriculum. Seoul: Korea Institute for Curriculum and Evaluation.

Hattie, J. (2009). Visible learning. A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. Oxon: Routledge.

Heo, H., Leppisaari, I., & Lee, O. (2018). Exploring learning culture in Finnish and south Korean classrooms. The Journal of Educational Research, 111(4), 459–472. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2017.1297924.

Hoffman, J. V., & Duffy, G. G. (2016). Does thoughtfully adaptive teaching actually exist? A challenge to teacher educators. Theory Into Practice, 55, 172–179. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2016.1173999.

Howard, H. C., & Hoffman, M. E. (2018). Variable-centred, person centred, and person-specific approaches: Where theory meets the methods. Organizational Research Methods, 21, 846–876.

Humphrey, N., Bartolo, P., Ale, P., Calleja, C., Hofsaess, T., Janikov, V., … Wetso, G.(2006). Understanding and responding to diversity in the primary classroom: an international study. European Journal of Teacher Education, 29(3), 305-318. doi https://doi.org/10.1080/02619760600795122.

Inspectorate of Education [Inspectie van het Onderwijs]. (2018a). De staat van het onderwijs. Utrecht: Inspectie van het Onderwijs, Ministerie van Onderwijs, Cultuur en Wetenschap Retrieved from https://www.onderwijsinspectie.nl/onderwerpen/staat-van-het-onderwijs.

Inspectorate of Education [Inspectie van het Onderwijs] (2018b). ONDERZOEKSKADER 2017 voor het toezicht op het voortgezet onderwijs. Retrieved from https://www.onderwijsinspectie.nl/onderwerpen/onderzoekskaders/documenten/rapporten/2018/07/13/onderzoekskader-2017-voor-het-toezicht-op-het-voortgezet-onderwijs.

Kang, N., & Hong, M. (2008). Achieving excellence in teacher workforce and equity in learning opportunities in South Korea. Educational Researcher, 37(4), 200–207. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X08319571.

Kankaras, M., Vermunt, J. K., & Moors, G. (2011). Measurement equivalence of ordinal items: a comparison of factor analytic, item response theory, and latent class approaches. Sociological Methods & Research, 40(2), 279–310. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124111405301.

Kennisnet (2017). Vier in balans-monitor 2017: de hoofdlijn. Retrieved from https://www.kennisnet.nl/publicaties/vier-in-balans-monitor/.

Keuning, T., van Geel, M., Frèrejean, J., van Merriënboer, J., Dolmans, D., & Visscher, A. J. (2017). Differentiëren bij rekenen: Een cognitieve taakanalyse van het denken en handelen van basisschoolleerkrachten. Pedagogische Studieën, 94(3), 160–181.

Kim, M. (2003). Teaching and learning in Korean classrooms: the crisis and the new approach? Asia Pacific Education Review, 4(2), 140–150. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03025356.

Kim, T., Cho, J.Y., Lee, B.G. (2012). Evolution to smart learning in public education: a case study of Korean public education. Paper presented at the IFIP WG 3.4 International Conference, OST 2012, Tallinn, Estonia, July 30 – August 3.

Kim, J., Han, I., Park, M., & Lee, J. K. (2013). Mathematics education in Korea. In Curricular and teaching and learning practices. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Co. Ptd. Ltd..

Klieme, E., Pauli, C., & Reusser, K. (2009). The Pythagoras study. Investigating effects of teaching and learning in Swiss and German mathematics classrooms. In T. Janik (Ed.), The power of video studies in investigating teaching and learning in the classroom (pp. 137–160). Münster: Waxmann.

Ko, J., Sammons, P., & Bakkum, L. (2013). Effective teaching: a review of research and evidence. CfBT Education Trust.

Kulik, C. C., et al. (1990). Effectiveness of mastery learning programs: a meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 60(2), 265–299. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543060002265.

Kyriakides, L., Creemers, B. P. M., & Antoniou, P. (2009). Teacher behaviour and student outcomes: suggestions for research on teacher training and professional development. Teaching and Teacher Education, 25, 12–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2008.06.001.

Kyriakides, L., Christoforou, C., & Charalambous, C. Y. (2013). What matters for student learning outcomes: a meta-analysis of studies exploring factors of effective teaching. Teaching and Teacher Education, 36, 143–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2013.07.010.

Lee, B. (2016). Secondary science teachers’ concepts of good science teaching. Journal of the Korean Association for Science Education, 36(1), 103–112. https://doi.org/10.14697/jkase.2016.36.1.0103.

Magidson, J., & Vermunt, J. K. (2004). Laten class model. In D. Kaplan (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of quantitative methodology for social sciences. SAGE. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412986311.n10.

Martin, M. O., Mullis, I. V. S., Foy, P., & Hooper, M. (2016a). TIMSS 2015 international results in mathematics. Boston: TIMMS & PIRLS International Study Center, Lynch School of Education, Boston College.

Martin, M. O., Mullis, I. V. S., Foy, P., & Hooper, M. (2016b). TIMSS 2015 international results in science. Boston: TIMMS & PIRLS International Study Center, Lynch School of Education.

Maulana, R., Helms-Lorenz, M., & Van de Grift, W. (2015). Development and evaluation of a questionnaire measuring pre-service teachers’ teaching behaviour: A Rasch modelling approach. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 26, 169–194.

McMullen, J., van Hoof, J., Degrande, T., Verschaffel, L., & van Dooren, W. (2018). Profiles of rationale number knowledge in Finnish and Flemish students – a multigroup latent class analysis. Learning and Individual Differences, 66, 70–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2018.02.005.

McQuarrie, L., McRae, P., & Stack-Cutler, H. (2008). Differentiated instruction provincial research review. Edmonton: Alberta Initiative for School Improvement.

Ministry of Education, Culture and Science. (2014). Plan van aanpak toptalenten 2014 - 2018. The Hague: Ministry of Education, Culture and Science.

Ministry of Education, Culture and Science. (2016). Actieplan gelijke kansen in het onderwijs. The Hague: Ministry of Education, Culture and Science.

Muijs, D., Kyriakides, L., van de Werf, G., Creemers, B., Timperley, H., & Earl, L. (2014). State of the art -- teacher effectiveness and professional learning. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 25(2), 231–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2014.885451.

Mullis, I. V. S., Martin, M. O., Foy, P., & Hooper, M. (2017). PIRLS 2016 international results in reading. Boston: TIMSS & PIRLS International Study Center, Lynch School of EducationBoston College and International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA).

Muthén, L.K, & Muthén, B.O. Re: What is a good value of entropy. 2007 [Online comment]. Retrieved from http://www.statmodel.com/discussion/messages/13/2562.html?1237580237.

Muthen, L. A., & Muthen, B. O. (2018). Mplus user’s guide. Eight edition. Los Angeles, CA. Retrieved from https://www.statmodel.com/download/usersguide/MplusUsersGuideVer_8.pdf.

National Center on Education and the Economy. (2018). South Korea: teacher and principal quality. Retrieved October 15, 2018 from http://ncee.org/what-we-do/center-on-international-education-benchmarking/top-performing-countries/south-korea-overview/south-korea-teacher-and-principal-quality/.

OECD (2012). Equity and quality in education. supporting disadvantaged students and schools. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264130852-en

OECD. (2014a). Education policy outlook: Netherlands. Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2014b). Talis 2013 results: an international perspective on teaching and learning. Paris: TALIS, OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2016b). Education policy outlook Korea. Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2016c). Netherlands 2016: foundations for the future. reviews of national policies for education. Paris: OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264257658-en.

OECD. (2016d). PISA 2015 results. In Policies and practices for successful schools (volume II). Paris: PISA, OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264267510-en.

OECD. (2016e). PISA 2015 results (volume I): excellence and equity in education. Paris: PISA, OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2017). PISA 2015 results: Students’ well-being. volume III. Paris: PISA, OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2018a). Education at a glance 2018: OECD indicators. Paris: OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/eag-2018-en.

OECD. (2018b). The resilience of students with an immigrant background. factors that shape well-being. Paris: OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264292093-en.