Abstract

Social sustainability is the generation of significant behaviors through balanced levels of education, learning and awareness so that the population has a good standard of living, achieves self-improvement and supports society. This can be achieved with various strategies, one of which is learning through games, which has gained popularity in recent years due to positive results. This is effectively achieved through serious gaming, which is growing steadily, mostly in education and healthcare. This type of strategy has been typically used in young populations with a transparent interaction with technological processes that facilitate its application. However, one cannot neglect other populations such as the elderly, who may experience a technology gap and may not perceive this type of initiative in the best light. The purpose of this article is to identify the different motivations that can encourage older adults to use serious games to encourage learning processes through technology. For this purpose, different previous research on gaming experiences with older adults has been identified, from which it was possible to categorize a series of factors that motivate this population. Subsequently, we represented these factors by means of a model of motivation for the elderly and, to be able to use it, we have defined a set of heuristics based on this model. Finally, we used the heuristics by means of a questionnaire to evaluate the design of serious gaming for older adults, obtaining positive results for the use of these elements to guide the design and construction of serious games for learning in older adults.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

In recent years, considerable research has been conducted on the benefits of games in human development, starting at an early age and focusing on sensory and motor development. This later becomes a symbolic process developing language, fostering imagination and creativity through the simulation of situations, objects or characters [1]. Then, when a young person becomes an adult, the motivations that lead them to play change, particularly emotional goals, perceived benefits, participation, keeping busy, social interaction, gaining benefits, learning, and consolidating social sustainability [2,3,4,5]. With respect to sustainability, educational processes are key because they are a mechanism through which people are sensitized and taught and through which sustainable culture is applied. It is important to highlight their importance through fun and meaningful experiences that encourage processes of support to society and good daily practices [6]. Given these advantages, it is understandable that in recent years’ games have been explored as mechanisms for skill development or knowledge acquisition through learning in the field of education. This means that there are several educational games that have proven to be successful when used in schools, higher education and training institutions.

The historical events that occurred recently with the COVID-19 pandemic forced many people to embrace technology in various areas of knowledge such as health, socio-politics, economics and education. This has led to a generation of an ongoing digital transformation process. For younger populations who have had contact with technology from an early age, this may not have been a major challenge, however, for the older population who had this technological contact at a much older age, it posed a more difficult challenge. Some of the challenges faced by this population included the processes of training, learning and knowledge acquisition, which during this period were only possible via technology. Therefore, the first difficulty was encountered, since most of the technological experiences that have been developed are mainly focused on a younger population with different characteristics and needs. This can lead to rejection by the older population because they do not feel comfortable with the mechanisms provided or because of a lack of interest in giving these technological means a chance to satisfy their needs, and even more so if they are delivered through the concept of games.

That is why this article aims to identify the motivating factors of older adults that can lead to engaging in these experiences of serious games for knowledge acquisition and learning processes. The main objective is that older adults can access these games using technological elements and that they can be used in the best possible way. The document is organized as follows: Sect. 2 provides a brief description of the definition of serious games and their relationship with older adults, in addition to some related works; Sect. 3 provides a detailed explanation of the different motivational aspects that were identified in this population for the use of serious games; Sect. 4 focuses on describing the validation process concerning the motivational aspects identified in older adults; Sect. 5 presents the results obtained; finally, Sect. 6 presents our discussion, conclusions and future lines of work.

2 Related work: serious games and older adults

The concept of the first serious game appeared in 1970 [7], although in the context of board games and not digital games, and since then other authors have analyzed the concept of serious games according to different approaches and uses [8,9,10]. For example, Marczewski [11] defines a serious game as a complete game in which the purpose of playing is not pure entertainment, but educational, meaningful and purposeful. Although, as noted, education provides an ideal field for the development of serious games, it is not the only purpose for which they have been used and there are proposals for serious games in other disciplines or application areas [12,13,14]. With the support of motion-monitoring devices and advances in virtual and augmented reality, gaming can also incorporate physical challenges, allowing serious games to be enhanced by incorporating game-based experiences such as exergaming [15], geolocated games and pervasive gaming concepts [16].

The first paper on the application of digital games with a serious focus on older adults is from 1987. The objective of this paper was to evaluate the cognitive improvement that could be achieved through these games, specifically in response times for decision making [17]. From this research to date, the landscape has not changed much, with cognitive processing, physical activity and social interaction being the main focus. All this has been achieved by making use of different devices such as PCs, consoles, and sensors such as Kinect, and Nintendo Wii controllers, among others [18]. The constant innovation of new technologies in games that offer different experiences and sensations to players has become commonplace. This not only allows it to be applied for entertainment purposes but also enables it to be constantly improved in a serious way whether it is for learning or any other important approach [19].

Some previous research involving the application of serious games with an educational approach for older adults has focused on promoting learning for training in the use of technology, and promoting the social and digital inclusion of this target audience. In this case, they not only learn about the use of technology but also about the perceived benefits of using the games [2, 20,21,22,23,24]. Efforts have also focused on user-centered design processes in serious educational online games in order to provide usability elements targeted at this population [25]. Other initiatives focus on teaching older adults through serious educational games to take an active approach to aging by means of virtual tutoring systems [26].

Research on the identification of the motivations of older adults to experience serious games is not focused on the education sector, but on the promotion of physical activity and rehabilitation processes in older adults [27,28,29,30]. There are also review and research processes to identify motivation in older adults, but with digital games focused on fun and entertainment [4, 18, 20, 31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38]. Other research has focused on the motivations of older adults, but not in terms of serious games, but in terms of the use of technology [39]. Finally, there is some research aimed at identifying motivations in older adults based on existing models such as the Self Determination Theory model (SDT) [4, 5, 40, 41] and the Emotional Processes and Self-Regulation model. [42].

3 Motivation model in older adults

The experiences generated in the interaction of older adults and a technological product, in this case, games, are traditionally analyzed from the field of Human–Computer Interaction (HCI). To this end, techniques and tools designed to be used in a general population are applied to determine the impact of games on older adults [43]. Although there are different means of evaluation to measure this experience [44], the older adult population presents a series of unique features that make it necessary to adjust or add new elements to the available means of evaluation to generate an objective evaluation. However, these adjustments or adaptations prove insufficient to evaluate the context of games due to the area’s specific and subjective elements [45, 46], and even more so when the traditional concept of usability is used instead of the concepts of playability.

Some of these tools described above include the Game Experience Questionnaire (GEQ) [47], Player Experience Need Satisfaction (PENS) [48], System Usability Scale (SUS) [49], Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) [50], among others. Therefore, the particularities and motivations of older adults need to be identified in order to help determine the adjustments to be made or to generate new processes for the evaluation of the Player eXperience (PX) [45] of older adults in digital games on an objective and solid basis. To clearly understand the concept of playability and PX, two points of view must be considered. First of all, we will consider the game as a software product that needs to be analyzed in depth to determine its quality. Traditionally the property of “Playability” has been used for this purpose due to its capacity to adapt the property of usability to game systems and because it is a more accurate measure of how much fun a game is. Secondly, there is the quality of the “Player Experience”, which is directly related to the concept of User Experience (UX), but which, when referring to the context of games, should be treated differently, just like PX. Although the difference between the two is based on the experience that the game offers players, they should be addressed using more subjective and personal measures such as “emotion”, “satisfaction” or “engagement”, which are key to describing and improving the interactive experience that humans enjoy when playing games [45, 51].

Based on the above, older adults, like any other population, have their own particularities not only on a physical and cognitive level but also with respect to what motivates a person to play and interact with playful experiences by means of technology [52]. In the case of older adults, these motivations must be identified and understood in order to design serious games with a focus on learning that will truly appeal to them, generating enjoyable processes and positive experiences.

Younger players are most motivated by fantasy, as they look for engaging fantasy experiences that satisfy their inquisitiveness, their need to learn, and their imagination [53]. It is normal for young people to try to challenge themselves by achieving goals and pursuing rewards. Young adults are motivated by rewarding experiences with attractive multimedia elements. A wide variety of motivations can be found in the case of older adults given that they are a heterogeneous group [54,55,56], some of which include perceived benefits, participation, keeping busy, acquiring knowledge, or obtaining a benefit [2,3,4,5].

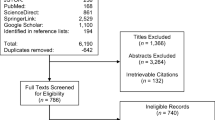

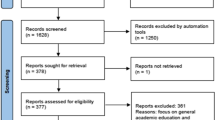

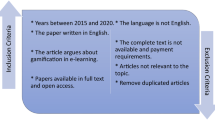

In order to obtain a model of what factors motivate older adults, a preliminary process was carried out to identify papers where older adults used game experiences. We conducted this identification process by means of a systematic review [57] in which we obtained detailed information on the different motivational elements in game-based systems for older adults, including serious games. This process aimed to answer different research questions targeting older adults, among which was their acceptance of the use of games via technology, and which game mechanics and dynamics were the most used and accepted by this population. To carry out this research, the methodology established by Kitchenham and Charters was applied [58], which defines a series of steps or phases for the application of systematic reviews in the field of software. For the selection of papers, a search string was defined using logical operators and relevant words to efficiently filter the results to be obtained. Following the basic methodology, a series of inclusion and exclusion criteria were defined to reduce the total number of articles to be addressed for the definition of what is proposed here (see Fig. 1). This process resulted in the identification of a series of aspects that help motivate older adults, as summarized in Fig. 2, and which will be described in detail below.

3.1 Meaning as a key motivational element in learning

Older adults play to satisfy a variety of needs [59]. However, one of the main motivations behind the experience of serious games for learning is the utility or benefit that can be obtained in the implementation of the proposed activities. If the older adult misperceives what a serious game is, they might not see any benefit in this type of experience, and see it as merely a mechanism of leisure and entertainment that does not offer any real utility, that is to say, a system without a meaning that encourages its use [60]. Different areas of interest have been identified in which older adults value the usefulness or benefit in the implementation of serious games, and are motivated them to try them out. These include learning processes that promote emotional/social well-being and improved health [61].

3.2 Learning

Learning engages older adults in a participatory and positive quality of life [62]. They want the knowledge to be practical and transferable to their daily lives, which is essential in the cost/benefit evaluation process of making the decision to play. When playing, an older adult values the learning experience over enjoying their free time and allow themselves play the game repeatedly [2]. Social interaction mechanisms are additional factors that reinforce motivation in a learning process, making it possible to connect with education and with other players. This is evidenced in the game experiences documented in the WorthPlay project. In addition, it is necessary to reinforce participants with positive comments that help them gain self-confidence. [63]. Finally, content-based challenges and graduated levels of practice should be included, as these are additional motivational elements in the learning process [64].

3.3 Emotional wellness

The public health emergency caused by the COVID-19 pandemic has led to increased social distancing and mandatory home confinement. This has led the general population to adopt a more sedentary routine and has favored the appearance of psychosocial disorders of anxiety, depression and stress. These problems have intensified when, due to work or for reasons of necessity, people have been forced to go out and risk their health [65]. Family and social support is helpful in addressing the emotional well-being of older adults, not only in this atypical situation but also under normal conditions when the family structure changes. It is normal for the family structure to change when grandchildren have to go to school, children leave home or, in the worst case, the loss of a partner. This has a negative impact on older adults, generating loneliness and isolation [66]. For this reason, when designing games it is important to keep in mind that they function as an escape from reality, and have a positive impact on the mental state, self-esteem and mood of the older adult, and there is empirical evidence that games offer better results on an emotional level than on a physical one [67, 68]. An example of the application of serious games for emotional wellness is HiGame (Horticultural Interaction Game), which focuses on learning about and caring for plants and vegetables, and generates a state of relaxation and emotional balance (see Fig. 3).

HiGame for the wellness of older adults [69]

3.4 Social wellness

Older adults enjoy games that allow them to connect with people, and even give them the opportunity to contribute to the wellness of others [70]. This type of connection can also be used to connect with people with similar hobbies, offering them additional social activities or simply a means of communication, as well as being applied to immobile older adults or those with some type of disability. Digital games that offer the possibility of generating social connections exert a positive influence and a sense of wellness by reducing the feeling of loneliness [68]. In addition, the socialization that occurs is not only focused on meeting new people, but also on the exchange of experiences while facing the same challenge together or in competition [71].

Some research shows that face-to-face environments are more motivating, as older adults enjoy online environments less, regardless of whether the game is cooperative, collaborative, coactive or competitive [31, 72]. This is because they do not want technology to replace face-to-face contact, but take it as a means to support such interaction processes.

3.5 Health

Other factors that motivate the use of gaming systems for older adults are health and self-care benefits [73]. If immediate or potential benefits are perceived, older adults are willing to participate in game-based systems and determine whether or not to continue using them [74]. For this reason, when designing serious games, efforts should be focused on showing the older player the potential effects of their use on health, bearing in mind that they are interested in both preserving and improving it [75].

In order to encourage self-care in older adults, self-management and self-monitoring should be encouraged as training mechanisms to keep them engaged in the game. This is so that they can obtain the best possible benefits by remaining active and taking responsibility for their own physical well-being. Accomplishing this requires older adults to have the knowledge to understand the benefits of this process, the safe and intuitive means to facilitate its execution, and self-motivation [76, 77], all supported by a persuasive process that motivates them.

3.6 Participation

Evidence indicates that older adults are more motivated to take part when they participate with a partner or counterpart [78]. This generates significant social participation in terms of empathy, positive affect and behavioral engagement, especially among extroverted older adults with higher cognitive abilities [79]. The process of jointly achieving objectives implies that players must coordinate, which stimulates social participation. In addition, new roles emerge depending on the skill level of the players, often one player will assume command of the team to instruct another player on how to carry out certain tasks [78]. Another influential factor is whether the process of collaboration or cooperation takes place on a split or shared screen, since when players share the same screen, they can help each other and coordinate actions in a much easier and friendlier way. On the other hand, having split screens and not sharing the field of vision of the game requires a higher cognitive level and coordination, which can generate stress in the older adult.

3.7 Intergenerational activity

The generation gap has become a social problem, in which people, including older adults, see this process of social disengagement with younger generations as a normal part of the aging process. Serious games provide an intergenerational experience that encourages social interactions between different groups. This provides an interactive environment that fosters collaboration and cooperation, contributing to the decrease of age discrimination. It also breaks down stereotypes by fostering inclusion and mutual respect between youth and older adults [80, 81].

Although intergenerational experiences are a motivational factor, when designing serious games it should be kept in mind that a large difference in experience and technological skills between younger and older adults can cause an imbalance in the experience [82]. In these cases, young people could assume the role of teachers, leaders, and caregivers, encouraging them and teaching them the dynamics and mechanics of the game, answering questions, and correcting mistakes. The older adults could take on the role of students, followers and even storytellers [83]. In the case of intergenerational activities, as in social activities, play experiences should include an adaptive difficulty. This would provide a balanced experience between older and younger adults when the skill level in play differs greatly.

3.8 Recognition

Older adults tend to need recognition and want not only to learn but to teach and share their wisdom, values and life experiences. This works well in intergenerational contexts where they can provide such experiences to their younger counterparts. In local multiplayer contexts, older adults focus on sharing, helping and supporting each other and other players by teaching, learning and sharing positive experiences [31, 84]. In addition, through serious games, learning can be encouraged in response to their needs in their daily lives, such as driving skills or safe medication [85]. These spaces provide the opportunity to learn and teach, generating connections and increasing wellness.

In the process of designing a serious game, it must be understood that recognition can also be given with phrases or motivational elements in a game that provides the desired encouragement or praise [86]. This recognition is also achieved with a process of feedback from the game to the older adult, thus showing that the actions being performed are being recognized. Providing facilitating mechanisms in serious games and continuous feedback processes according to the actions performed increases the motivation for participation in this type of experience. In addition, guided instructions can be incorporated to reduce confusion and anticipated frustration [87, 88] (see Fig. 4).

Support and feedback in older adults [89]

3.9 Match with interests

Although this is subjective and depends on the tastes of each person, if the theme of the serious game is related to personal interests, it generates greater motivation in the older adult. In addition, if it satisfies the need for feedback, the sense of accomplishment is valued by the older adult. This appreciation is reflected in the enjoyment of accomplishing objectives and as a means of challenging oneself and learning by monitoring one’s own progress and accomplishments [90].

3.9.1 Adaptation and customization

Many older adults have shown interest in using technological elements, but find them too complex to master for proper use. This is why it is necessary to give the impression from the beginning that serious games are easy to use in order to motivate the participants to use them [91, 92]. The limitations in user-friendliness are not only oriented towards an intuitive and eye-catching graphical interface but also have to do with the game mechanics involved. It is necessary to offer easy-to-play games that use few buttons and do not generate a psychological burden.

The cost–benefit evaluation made by older adults is often focused on the learning process that they must go through for basic mastery of the controls that will allow interaction with the game, evaluated against the benefit they will obtain. If the return is less than the effort they are going to make, then the usefulness of the digital game is zero, and the same happens with systems that are very accessible and easy to use, but that provide few benefits when using them [31]. Additionally, in order to offer a comfortable experience to the participant, the game design should offer the possibility of adjusting game parameters to customize the experience, for example, adjusting text size, brightness and colors [38].

3.9.2 Friendly interaction

Research has shown that older adults prefer to interact with mobile devices and PCs, rather than traditional consoles such as Play Station or Xbox that use traditional controllers [90]. This is due to the type of peripherals used to interact with the system. For example, there is greater acceptance and motivation for direct and natural input devices, such as touch screens, which require simple actions. Conversely, when using a console controller with multiple buttons and joysticks for motion control, the complexity of coordinating both elements for movement and game interaction increases [93]. Touch screen devices such as smartphones and tablets are also more widely accepted by older adults because they allow them to play whenever they want due to their portability, ease of use and low configuration. However, depending on the visual capacity of the user, this device can become an unappealing element due to the size of the screen, in which case consoles are a better option [94].

As for natural interaction devices that use motion sensors, acceptance is based on the ease of interacting with the game. Devices such as Sony’s Play Move are problematic to use because they require additional button presses over and above the natural body movement process. On the contrary, devices such as Microsoft’s Kinect and Nintendo Wii are well received by this population, since they do not require this additional interaction process [95,96,97]

3.9.3 Make sense

In the design of serious games, efforts should focus on providing make sense to the actions performed by the older adult in the game. This is achieved through a coherent and interesting narrative, which drives motivation[38]. This narrative can be presented by a character that makes the player feel at ease, documented cases have shown that a boy or girl portraying a grandchild can achieve this feeling [98] (see Fig. 5). The stories presented cannot be too simple or cliché, nor should they encourage depression or pessimism. This population appreciates empathetic stories that stimulate their inquisitiveness, provide useful knowledge [85] and generate surprise and expectation [99].

Child avatar which reminds the elderly of their family [98]

3.9.4 Technology familiarity

Familiarity with technology in a serious game refers to the actionable familiarity needed to interact with the symbolic and cultural elements in the game. While one might expect that the older adult population would not have a different mindset than the leisure population about the usefulness of “gaming”, this changes when it comes to gamers with some experience with these types of systems [22].

The lack of knowledge about the use of modern technologies has a strong influence on the decision to use serious games. This is because it generates confusion about their use, fear of the unknown and lack of confidence in them [100]. A previous study identified that when older adults have full control over the technological platform where the game was played, they enjoyed it and participated more, regardless of whether it was on a mobile device or a console [94].

4 Materials and methods

4.1 Design

The model generated with the motivational aspects for older adults when participating in serious games with a learning approach (see Sect. 3) was used to design and propose a set of heuristics that can be used in the analysis of serious gaming in older adults. These heuristics were validated through the application of an expert evaluation. This base model is expected to be part of a much larger model that will include various aspects of playfulness in older adults with respect to game-based systems. In this case, we have focused on serious games from an older adult education perspective. It should be noted that it has not been initially evaluated by older adults since it would be ideal to have a prototype that has been previously evaluated using the heuristics to be evaluated by end users, but this was not implemented in this research because of limited access to this population given that most of them live in isolation.

Based on the model of motivational aspects that encourage the use of serious games for learning in older adults described above, the following heuristics, detailed in Table 1, are established that should be taken into account in order to provide motivating game experiences that engage the older adult.

4.2 Participants

Fourteen evaluators were recruited to conduct the evaluation, all of whom are academics with graduate training at a MSc or PhD level, expert researchers in the field of HCI and reported to have experience in heuristic evaluation, many of them with experience in the field of digital games. These evaluators are familiar with the principles and design needs and expressed their interest in participating in the evaluation without receiving any compensation for their participation. The participating evaluators come from Universidad Pontificia and Universidad Católica de Valparaíso—Chile, Universidad de Caldas—Colombia, Universidad de Granada—Spain, Universidad de la Frontera—Chile, Universidad de Medellín—Colombia, Universidad Antonio José Camacho—Colombia, and Universidad San Buenaventura—Colombia. The group of evaluators included two experts in the care and technological interaction of older adults and two anthropologists in order to provide an evaluation based on the motivations of human beings. As neither the experts in elderly care nor the anthropologists had any prior experience in heuristics, a previous training process was necessary to be able to carry out the process adequately.

4.3 Questionnaires

Based on the heuristics defined, we proceeded to establish the questionnaire to be answered by the expert evaluators, taking as a basis the methodology defined by Quiñones et al. [134] which establishes not only how to define heuristics, but also how to carry out a process of validation and evaluation of the heuristics. The evaluation was carried out online by the participants via a web form where the reason for the questionnaire, the different heuristics and their evaluation process were explained in detail (see Appendix A). This questionnaire consisted of a total of 54 questions, of which there were 4 questions for each heuristic focused on evaluating them individually with respect to dimensions of usefulness, clarity, ease of use and the need for a checklist as a complementary element. These questions used a 5-point Likert scale where a value of 1 indicates that the heuristic does not comply with its dimension and a value of 5 indicates that it complies completely. Each heuristic had an optional question to obtain additional information that the evaluator would like to provide. Three (3) additional questions were added to analyze the heuristics as a group, evaluating their ease of use, intention of use by the evaluators and their completeness, also structured with a Likert scale. Finally, one (1) optional question was added in order to complement missing information and also to obtain qualitative results. Below is a brief description of the dimensions evaluated for each heuristic from D1 to D4. The questions aimed at evaluating the heuristics as a group from Q1 to Q3. The question provided in each heuristic with an open response to obtain qualitative information from H1 to H10. The question to obtain qualitative information regarding to additional heuristics is included in C1 (see Table 2).

5 Results

The results of the responses are as follows, focusing on the individual analysis of the heuristic with respect to usefulness, ease, clarity and need for a checklist (see Table 3). The results for D1—Usefulness indicate that the average usefulness is high (4.69) and heuristic 10 is considered the most useful overall. The overall standard deviation of D1 is low (its range is 0–0.76). As for the results of D2—Clarity, its average is also high (4.54), ranging from 4.29 and 4.71 where heuristic 9 is the clearest of all. Its standard deviation is also low, with the lowest value in heuristic 9 (0.47) and the highest value in heuristics 1, 3, 6, 8 (0.85). As for the results of D3–Ease, although the average is the lowest overall, it is still an acceptable value (3.89). Heuristics 5 and 9 are the least easy to use with values of (3.36)—(3.64) and heuristics 3, 4, 6, 7 and 10 are the easiest. Their variance is one of the most significant with a range of 3.36—4.21. Its lowest standard deviation occurs with heuristic 4 (0.62). Finally, in terms of the need for a checklist for more details, it is very high (4.34). All heuristics acquired a high mean value with a minimum value of 4.14. In addition, heuristic 5 stands out as having the highest value. The heuristic with the lowest value is heuristic 1, but with a high standard deviation, with a value of 1.17.

The perceptions of the experts are similar for all dimensions except for the need for a checklist for heuristics 1, 2, 4, 10 and the ease of application for heuristics 3, 5, 9. This is due to the participation of some participants without much experience in the field of the application of expert judgment and the use of heuristics, such as anthropologists and experts in the care of older adults. In addition, it is evident that heuristics 5 and 9 do not show that they are easy to apply, so a revision of these heuristics will be made to make them more easily applicable irrespective of the area of knowledge.

The overall perception of the heuristics with respect to easiness, completeness and intention to use can be seen in Table 4. The perception of the intention to use the heuristics was the highest rated item with an average of 4.57, making the application of the set of heuristics presented attractive for the evaluators. For both the easiness of use and the completeness of the heuristics, positive results were obtained with an average of 4.21 and 4.36 respectively, and a standard deviation of 0.5 to 0.6, also showing positive comments for both the intention to use and the completeness presented, although as will be seen in the qualitative results, there are elements that could be improved.

Regarding the optional questions asked for each of the heuristics, only one evaluator provided an opinion on heuristic 4. The evaluator expressed confusion regarding the inclusion process indicated in the heuristic, relating it to the disability of older adults and not to a process of inclusion in social interaction based on cooperation and collaboration. Once the process was completed, we clarified the true intention of the inclusion of this population to the evaluator. As for heuristics 5 and 9, which were rated as the most difficult to use, additional information on these heuristics was obtained with repetitive comments from the evaluators who provided feedback (see Table 5).

Finally, the answers obtained in the last question on the heuristic or missing elements presented by the experts allowed to make some observations. Table 6 shows these observations and specifies whether they warrant a future revision of the heuristics on a case-by-case basis. It should be noted that one of the expert evaluators was satisfied with the completeness of the elements contemplated in the heuristic.

A format of heuristic specifications was defined for each of them based on the different comments made by the evaluators (see Appendix B). These contain different elements such as their nomenclature, their name, their priority, their definition, their detailed explanation, the characteristics of the serious game they affect, the benefits of their application and their possible interpretation problems. Prioritization of these elements was established at three levels according to the guiding methodology defined by Quiñones et al. [134]: (1) useful, (2) important, (3) critical. A heuristic set such as (1) indicates that the heuristic, although useful, can be improved. A ranking of (2) states that the heuristic is important and should be considered, but is not mandatory because it depends on the application context. Finally, priority (3) establishes a key heuristic that must always be met.

6 Conclusions

The design and construction of serious games for learning processes are directed at a young public that does not adjust to the needs and particularities of older adults, nor to their motivations. This research offers advances in the design of serious games focused on learning in older adults, contributing a base model with different motivational aspects that should be taken into account to achieve greater use of these games by this population. This model was tested through an evaluation by experts in the field of HCI, achieving positive results. These results showed that the new heuristics were perceived as easy to use and useful and the participants expressed their intention to use them if working with the older adult population.

The responses were generally homogeneous and both quantitative and qualitative results were obtained. According to the feedback results of the evaluations, a set of new recommendations have been identified for the design and construction of serious games focused on learning in older adults, such as the inclusion of examples that guide the correct understanding and implementation of the heuristics, aspects of playability, game times, specification of adaptive elements, activities not only for groups but also for individuals, examples of game mechanics and some examples of specific application to a population with some type of disability.

Following a methodology in the process of defining and evaluating heuristics facilitates the tasks to be performed, since there are defined tasks and validation methods. The results obtained through the application of the chosen methodology also showed an aspect where there was no complete uniformity in the evaluators’ answers, related to the need for checklists as a complementary element to the design and implementation process. Heuristics 1, 2, 4 and 10 show deviations greater than 1, so this aspect should be reviewed in greater depth. This is also considered a difficulty in the execution process.

Although we did not proceed to an empirical validation with older adults through a functional prototype, the results obtained will facilitate and guide future construction of the prototype with the help of experts and end users. These results drive and encourage construction that is more centered on the needs and particularities of older adults. Future extensions of this research should include tests applied directly to end users supported by a functional prototype of a serious game focused on learning processes. In addition, although the initial results are promising, further research is needed to focus efforts not only on serious games with an educational focus but on game-based systems in general in order to identify a broader set of motivations in older adults and achieve a degree of satisfaction and enjoyment in them, further encouraging the use of new technologies. Finally, more complete heuristic specification forms should be generated, including checklists to guide inexperienced evaluators in the process, or, due to the complexity of the heuristic, provide an application guide.

References

Piaget, J., Inhelder, B.: Psicologia del niño. (1997).

Seah, E.T.W., Kaufman, D., Sauvé, L., Zhang, F.: Play, learn, connect: older adults’ experience with a multiplayer, educational, digital bingo game. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 56, 675–700 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1177/0735633117722329

Birk, M. V., Friehs, M.A., Mandryk, R.L.: Age-based preferences and player experience: A crowdsourced cross-sectional study. CHI Play 20170-Proc. Annu. Symp. Comput. Interact. Play. (2017). https://doi.org/10.1145/3116595.3116608.

Subramanian, S., Dahl, Y., Skjæret Maroni, N., Vereijken, B., Svanæs, D.: Assessing motivational differences between young and older adults when playing an exergame. Games Health J. 9, 24–30 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1089/g4h.2019.0082

Ryan, R.M., Deci, E.L.: Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 55, 68–78 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

Tsalapatas, H., Heidmann, O., Houstis, E.: A serious game for digital skill building among individuals at risk, promoting employability and social inclusion. In: de Carvalho, C., Escudeiro, P., Coelho, A. (eds.) Serious Games, Interaction and Simulation, pp. 91–98. Springer International Publishing, Cham (2017)

Wilson, J.P.: Serious games: The art and science of games that simulate life. New York: Viking Press. (1970). https://doi.org/10.1177/104687817000100406

Klabbers, J.H.G.: Terminological ambiguity: Game and simulation. Simul Gaming 40, 446–463 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1177/1046878108325500

Connolly, T.M., Boyle, E.A., MacArthur, E., Hainey, T., Boyle, J.M.: A systematic literature review of empirical evidence on computer games and serious games. Comput. Educ. 59, 661–686 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.COMPEDU.2012.03.004

Djaouti, D., Alvarez, J., Jessel, J.-P.: LudoScience - Classifying Serious Games: The G/P/S Model (Broacasting our studies), http://www.ludoscience.com/EN/diffusion/537-Classifying-Serious-Games-The-GPS-Model.html, last Accessed 2022 Jan 06.

Marczewski, A.: Game Thinking. In: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. (ed.) Even Ninja Monkeys Like to Play: Gamification, Game Thinking and Motivational Design. p. 15. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform (2015)

Dobrovsky, A., Borghoff, U.M., Hofmann, M.: Applying and augmenting deep reinforcement learning in serious games through interaction. Period. Polytech. Electr. Eng. Comput. Sci. 61, 198–208 (2017). https://doi.org/10.3311/PPee.10313

Kalogiannakis, M., Papadakis, S., Zourmpakis, A.I.: Gamification in science education. A systematic review of the literature. Educ. Sci. 11, 1–36 (2021). https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11010022

Guillén-Nieto, V., Aleson-Carbonell, M.: Serious games and learning effectiveness: The case of It’s a Deal! Comput. Educ. 58, 435–448 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.COMPEDU.2011.07.015

Tahmosybayat, R., Baker, K., Godfrey, A., Caplan, N., Barry, G.: Move Well: Design Deficits in Postural Based Exergames. What are We Missing? 2018 IEEE Games, Entertain. Media Conf. GEM 2018. (2018). https://doi.org/10.1109/GEM.2018.8516516.

Arango-López, J., Gallardo, J., Gutiérrez, F.L., Cerezo, E., Amengual, E., Valera, R.: Pervasive games: Giving a meaning based on the player experience. In: ACM International Conference Proceeding Series. pp. 1–4. Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA (2017). https://doi.org/10.1145/3123818.3123832.

Clark, J.E., Lanphear, A.K., Riddick, C.C.: The effects of videogame playing on the response selection processing of elderly adults. J. Gerontol. 42, 82–85 (1987). https://doi.org/10.1093/geronj/42.1.82

Rienzo, A., Cubillos, C.: Playability and player experience in digital games for elderly: A systematic literature review. Sensors (Switzerland). 20, 1–23 (2020). https://doi.org/10.3390/s20143958

Kasapakis, V., Gavalas, D.: Pervasive gaming: Status, trends and design principles. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 55, 213–236 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JNCA.2015.05.009

Possler, D., Klimmt, C., Schlütz, D., Walkenbach, J.: A Mature Kind of Fun? Exploring Silver Gamers’ Motivation to Play Casual Games – Results from a Large-Scale Online Survey. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. (including Subser. Lect. Notes Artif. Intell. Lect. Notes Bioinformatics). 10298, 280–295 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-58536-9_23.

Fiorini, J.M., Barros, D.J.R., M., Bento, E.B.: Gamification to promote digital inclusion of the elderly. Conf. Inf. Syst. Technol. Cist, Iber (2017). https://doi.org/10.23919/CISTI.2017.7975708

Greipl, S., Moeller, K., Kiili, K., Ninaus, M.: Different performance, full experience: A learning game applied throughout adulthood. Int. J. Serious Games. 7, 61–80 (2020)

Poulova, P., Simonova, I.: Blended Learning as Means of Support Within the Elderly People Education. In: Cheung, S.K.S., Kwok, L., Ma, W.W.K., Lee, L.-K., and Yang, H. (eds.) Blended Learning. New Challenges and Innovative Practices. pp. 3–14. Springer International Publishing, Cham (2017).

Wouters, E.J.M., Nieboer, M.E., Nieboer, K.A., Moonen, M.J.G.A., Peek, S.T.M., Sponselee, A.-M.A.G., van Hoof, J., van der Voort, C.S., Luijkx, K.G.: How to Guide the Use of Technology for Ageing-in-Place? An Evidence-Based Educational Module. In: Zhou, J. and Salvendy, G. (eds.) Human Aspects of IT for the Aged Population. Aging, Design and User Experience. pp. 486–497. Springer International Publishing, Cham (2017).

Sauvé, L., Kaufman, D.: User-Centered design: an effective approach for creating online educational games for seniors. Commun. Comput. Inf. Sci. 1220, 262–284 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-58459-7_13

Cesta, A., Cortellessa, G., De Benedictis, R., Fracasso, F.: ExPLoRAA: An intelligent tutoring system for active ageing in (Flexible) time and space. CEUR Workshop Proc. 2333, 92–109 (2019)

Smeddinck, J.D., Herrlich, M., Malaka, R.: Exergames for Physiotherapy and Rehabilitation: A Medium-Term Situated Study of Motivational Aspects and Impact on Functional Reach. In: Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. pp. 4143–4146. Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA (2015). https://doi.org/10.1145/2702123.2702598.

Seaborn, K., Pennefather, P., Fels, D.I.: Eudaimonia and hedonia in the design and evaluation of a cooperative game for psychosocial well-being. Human-Comput. Interact. 35, 289–337 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1080/07370024.2018.1555481

Kappen, D.L., Nacke, L.E., Gerling, K.M., Tsotsos, L.E.: Design strategies for gamified physical activity applications for older adults. Annu. Hawaii Int. Conf. Syst. Sci, Proc (2016). https://doi.org/10.1109/HICSS.2016.166

Marcos-Pardo, P.J., Martínez-Rodríguez, A., Gil-Arias, A.: Impact of a motivational resistance-training programme on adherence and body composition in the elderly OPEN. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-19764-6.

Nap, H.H., Kort, Y.A.W. De, IJsselsteijn, W.A.: Senior gamers: Preferences, motivations and needs. Gerontechnology. 8, 0–16 (2009). https://doi.org/10.4017/gt.2009.08.04.003.00.

Yu, R.W.L., Yuen, W.H., Peng, L., Chan, A.H.S.: Acceptance Level of Older Chinese People Towards Video Shooting Games. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. (including Subser. Lect. Notes Artif. Intell. Lect. Notes Bioinformatics). 12208 LNCS, 707–718 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-50249-2_50.

Ahmad, F., Zongwei, L., Ahmed, Z., Muneeb, S.: Behavioral profiling: a generationwide study of players’ experiences during brain games play. Interact. Learn. Environ. 0, 1–14 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2020.1827440.

De Vries, A.W., Van Dieën, J.H., Van Den Abeele, V., Verschueren, S.M.P.: Understanding Motivations and Player Experiences of Older Adults in Virtual Reality Training. Games Health J. 7, 369–376 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1089/g4h.2018.0008

Altmeyer, M., Lessel, P., Krüger, A.: Investigating gamification for seniors aged 75+. DIS 2018 - Proc. 2018 Des. Interact. Syst. Conf. 453–458 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1145/3196709.3196799.

Razak, F.H.A., Azhar, N.H.C., Adnan, W.A.W., Nasruddin, Z.A.: Exploring Malay older user motivation to play mobile games. (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-70010-6_44

Chesham, A., Wyss, P., Müri, R.M., Mosimann, U.P., Nef, T.: What older people like to play: Genre preferences and acceptance of casual games. JMIR Serious Games. 5, 1–11 (2017). https://doi.org/10.2196/games.7025

Carvalho, R.N.S. De, Ishitani, L.: Motivational Factors for Mobile Serious Games for Elderly Users. XI Simpósio Bras. Jogos e Entretenimento Digit. - SBGames 2012. 19–28 (2012).

Yang, H.L., Lin, S.L.: The reasons why elderly mobile users adopt ubiquitous mobile social service. Comput. Human Behav. 93, 62–75 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.12.005

Khalili-Mahani, N., de Schutter, B., Sawchuk, K.: The Relationship Between the Seniors’ Appraisal of Cognitive-Training Games and Game-Related Stress Is Complex: A Mixed-Methods Study. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. (including Subser. Lect. Notes Artif. Intell. Lect. Notes Bioinformatics). 12426 LNCS, 586–607 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-60149-2_45.

Khalili-Mahani, N., De Schutter, B.: Affective game planning for health applications: Quantitative extension of gerontoludic design based on the appraisal theory of stress and coping. JMIR Serious Games. 7, 1–18 (2019). https://doi.org/10.2196/13303

Carstensen, L.L., Hartel, C.R.: When I’m 64. National Academies Press (US) (2006). https://doi.org/10.17226/11474.

Chu, K., Wong, C.Y., Khong, C.W.: Methodologies for evaluating player experience in game play. Commun. Comput. Inf. Sci. 173 CCIS, 118–122 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-22098-2_24.

Sánchez, J.L.G., Vela, F.L.G., Simarro, F.M., Padilla-Zea, N.: Playability: Analysing user experience in video games. Behav. Inf. Technol. 31, 1033–1054 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2012.710648

Salazar Cardona, J., Gutiérrez Vela, F.L., Lopez Arango, J., Gallardo, J.: Game-based systems: Towards a new proposal for playability analysis. CEUR Workshop Proc. 3082, 47–56 (2021)

González, J.L., Gutierrez, F.L.: Caracterización de la experiencia del jugador en videojuegos., (2010).

Ijsselsteijn, W.A., Kort, D., Poels, Y.A.W.&: GAME EXPERIENCE QUESTIONNAIRE. Technische Universiteit Eindhoven (2013).

Rigby, S., Ryan, R.: The Player Experience of Need Satisfaction (PENS) An applied model and methodology for understanding key components of the player experience. (2004).

Brooke, J.: SUS: A “Quick and Dirty” Usability Scale. In: Usability Evaluation In Industry. pp. 207–212 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1201/9781498710411-35.

Davis, F.D.: Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. Manag. Inf. Syst. 13, 319–339 (1989). https://doi.org/10.2307/249008

Isbister, K., Schaffer, N.: The Four Fun Keys. In: Game Usability. pp. 317–343. Elsevier (2008). https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-374447-0.00020-2.

Cota, T.T., Ishitani, L., Vieira, N.: Mobile game design for the elderly: A study with focus on the motivation to play. Comput. Human Behav. 51, 96–105 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.04.026

Xu, W., Liang, H.N., Yu, K., Baghaei, N.: Efect of Gameplay Uncertainty, Display Type, and Age on Virtual Reality Exergames. Conf. Hum. Factors Comput. Syst. - Proc. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1145/3411764.3445801.

Sayago, S., Rosales, A., Righi, V., Ferreira, S.M., Coleman, G.W., Blat, J.: On the conceptualization, design, and evaluation of appealing, meaningful, and playable digital games for older people. Games Cult. 11, 53–80 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412015597108

IJsselsteijn, W., Nap, H.H., De Kort, Y., Poels, K.: Digital game design for elderly users. Proc. 2007 Conf. Futur. Play. Futur. Play ’07. 17–22 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1145/1328202.1328206.

Santos, L.H., Okamoto, K., Hiragi, S., Yamamoto, G., Sugiyama, O., Aoyama, T., Kuroda, T.: Pervasive game design to evaluate social interaction effects on levels of physical activity among older adults. J. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. Eng. 6, 205566831984444 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1177/2055668319844443

Salazar, J.A., Arango, J., Gutiérrez, F.L., Moreira, F.: Older adults and games from a perspective of playability, game experience and pervasive environments: A systematics literature review. World Conf. Inf. Syst. Technol. 2022, 444–453 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-04819-7_42

Kitchenham, B., Charters, S.: Guidelines for performing systematic literature reviews in software engineering. Engineering 2, 1051 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1145/1134285.1134500

De Schutter, B., Malliet, S.: The older player of digital games: A classification based on perceived need satisfaction. Communications 39, 67–88 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1515/commun-2014-0005

Brown, J.A.: Digital gaming perceptions among older adult non-gamers. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. (including Subser. Lect. Notes Artif. Intell. Lect. Notes Bioinformatics). 10298, 217–227 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-58536-9_18.

Gerling, K.M., Mandryk, R.L., Linehan, C.: Long-term use of motion-based video games in care home settings. Conf. Hum. Factors Comput. Syst. - Proc. 2015-April, 1573–1582 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1145/2702123.2702125.

World Health Organization: WHO | 10 facts on ageing and the life course, https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/10-facts-on-ageing-and-health, last Accessed 2022 May 30.

Marston, H.R.: Design recommendations for digital game design within an ageing society. Educ. Gerontol. 39, 103–118 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1080/03601277.2012.689936

Kaufman, D., Sauvé, L., Renaud, L., Sixsmith, A., Mortenson, B.: Older Adults’ digital gameplay: patterns, benefits, and challenges. Simul. Gaming. 47, 465–489 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1177/1046878116645736

Leite Araujo, R., Da Silva Sena, T., Takako Endo, P.: Gamification applied to an elderly monitoring system during the COVID-19 pandemic. IEEE Lat. Am. Trans. 19, 1074–1082 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1109/tla.2021.9451254

Shao, D., Lee, I.J.: Acceptance and influencing factors of social virtual reality in the urban elderly. Sustain. 12, 1–19 (2020). https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229345

Rosenberg, D., Depp, C.A., Vahia, I.V., Reichstadt, J., Palmer, B.W., Kerr, J., Norman, G., Jeste, D.V.: Exergames for subsyndromal depression in older adults: A pilot study of a novel intervention. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 18, 221–226 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181c534b5

Kaufman, D.: Socioemotional Benefits of Digital Games for Older Adults. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. (including Subser. Lect. Notes Artif. Intell. Lect. Notes Bioinformatics). 10298, 242–253 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-58536-9_20.

Wu, Y.S., Chang, T.W., Datta, S.: HiGame: Improving elderly well-being through horticultural interaction. Int. J. Archit. Comput. 14, 263–276 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1177/1478077116663349

De Schutter, B., Vanden Abeele, V.: Designing meaningful play within the psycho-social context of older adults. ACM Int. Conf. Proceeding Ser. 84–93 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1145/1823818.1823827.

Goršič, M., Darzi, A., Novak, D.: Comparison of two difficulty adaptation strategies for competitive arm rehabilitation exercises. IEEE Int. Conf. Rehabil. Robot. 640–645 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICORR.2017.8009320.

Gajadhar, B.J., Nap, H.H., De Kort, Y.A.W., Ijsselsteijn, W.A.: Out of sight, out of mind: Co-player effects on seniors’ player experience. ACM Int. Conf. Proceeding Ser. 74–83 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1145/1823818.1823826.

Roberts, A.R., De Schutter, B., Franks, K., Radina, M.E.: Older Adults’ experiences with audiovisual virtual reality: perceived usefulness and other factors influencing technology acceptance. Clin. Gerontol. 42, 27–33 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1080/07317115.2018.1442380

Khalili-Mahani, N., Assadi, A., Li, K., Mirgholami, M., Rivard, M.E., Benali, H., Sawchuk, K., De Schutter, B.: Reflective and reflexive stress responses of older adults to three gaming experiences in relation to their cognitive abilities: Mixed methods crossover study. JMIR Ment. Heal. 7, (2020). https://doi.org/10.2196/12388.

Löckenhoff, C.E., Carstensen, L.L.: Socioemotionol selectivity theory, aging, and health: The increasingly delicate balance between regulating emotions and making tough choices. J. Pers. 72, 1395–1424 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00301.x

Merilampi, S., Koivisto, A., Sirkka, A., Raumonen, P., Virkki, J., Xiao, X., Min, Y., Ye, L., Chujun, X., Chen, J.: The cognitive mobile games for older adults-A Chinese user experience study. 2017 IEEE 5th Int. Conf. Serious Games Appl. Heal. SeGAH 2017. (2017). https://doi.org/10.1109/SeGAH.2017.7939280.

Merilampi, S., Koivisto, A., Virkki, J.: Activation game for older adults - Development and initial user experiences. 2018 IEEE 6th Int. Conf. Serious Games Appl. Heal. SeGAH 2018. 1–5 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1109/SeGAH.2018.8401351.

Mace, M., Kinany, N., Rinne, P., Rayner, A., Bentley, P., Burdet, E.: Balancing the playing field: Collaborative gaming for physical training. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 14, 1–19 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12984-017-0319-x

Pereira, F., Bermudez I Badia, S., Jorge, C., Da Silva Cameirao, M.: Impact of Game Mode on Engagement and Social Involvement in Multi-User Serious Games with Stroke Patients. Int. Conf. Virtual Rehabil. ICVR. 2019-July, 1–14 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICVR46560.2019.8994505.

Zhou, J., Salvendy, G.: Human aspects of IT for the aged population applications, services and contexts: Third international conference, ITAP 2017 held as part of HCI international 2017 vancouver, BC, Canada, july 9–14, 2017 proceedings, Part II. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. (including Subser. Lect. Notes Artif. Intell. Lect. Notes Bioinformatics). 10298, (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-58536-9.

Cerezo, E., Blasco, A.C.: The Space Journey game: An intergenerational pervasive experience. Conf. Hum. Factors Comput. Syst. - Proc. 1–6 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1145/3290607.3313055.

Vanden Abeele, V., De Schutter, B.: Designing intergenerational play via enactive interaction, competition and acceleration. Pers. Ubiquitous Comput. 2009 145. 14, 425–433 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/S00779-009-0262-3.

Zhang, F.: Intergenerational Play Between Young People and Old Family Members: Patterns, Benefits, and Challenges. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. (including Subser. Lect. Notes Artif. Intell. Lect. Notes Bioinformatics). 10926 LNCS, 581–593 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92034-4_44.

Pearce, C.: The Truth About Baby Boomer Gamers: A Study of Over-Forty Computer Game Players. Games Cult. 142–174 (2008).

Wang, Y.L., Hou, H.T., Tsai, C.C.: A systematic literature review of the impacts of digital games designed for older adults. Educ. Gerontol. 46, 1–17 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1080/03601277.2019.1694448

Lee, S., Oh, H., Shi, C.K., Doh, Y.Y.: Mobile game design guide to improve gaming experience for the middle-Aged and older adult population: User-centered design approach. JMIR Serious Games. 9, 1–18 (2021). https://doi.org/10.2196/24449

Velazquez, A., Martínez-García, A.I., Favela, J., Ochoa, S.F.: Adaptive exergames to support active aging: An action research study. Pervasive Mob. Comput. 34, 60–78 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmcj.2016.09.002

Zhang, F., Hausknecht, S., Schell, R., Kaufman, D.: Factors affecting the gaming experience of older adults in community and senior centres. Commun. Comput. Inf. Sci. 739, 464–475 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-63184-4_24

Broneder, E., Weiß, C., Puck, M., Puck, S., Sandner, E., Papp, A., Fernández Domínguez, G., Sili, M.: TACTILE – A Novel Mixed Reality System for Training and Social Interaction. Commun. Comput. Inf. Sci. 1226 CCIS, 12–20 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-50732-9_2.

Tabak, M., De Vette, F., Van DIjk, H., Vollenbroek-Hutten, M.: A game-based, physical activity coaching application for older adults: Design approach and user experience in daily life. Games Health J. 9, 215–226 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1089/g4h.2018.0163

Loos, E.: Exergaming: Meaningful Play for Older Adults? Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. (including Subser. Lect. Notes Artif. Intell. Lect. Notes Bioinformatics). 10298, 254–265 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-58536-9_21.

Vasconcelos, A., Silva, P.A., Caseiro, J., Nunes, F., Teixeira, L.F.: Designing tablet-based games for seniors: The example of CogniPlay, a cognitive gaming platform. ACM Int. Conf. Proceeding Ser. 1–10 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1145/2367616.2367617.

Doroudian, A., Loos, E., Ter Vrugt, A., Kaufman, D.: Designing an Online Escape Game for Older Adults: The Implications of Playability Testing Sessions with a Variety of Dutch Players. (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-50249-2_42.

Jali, S.K., Arnab, S.: The perspectives of older people on digital gaming: Interactions with console and tablet-based games. Lect. Notes Inst. Comput. Sci. Soc. Telecommun. Eng. LNICST. 176 LNICST, 82–90 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-51055-2_11.

Niksirat, K.S., Silpasuwanchai, C., Ren, X., Wang, Z.: Towards cognitive enhancement of the elderly: A UX study of a multitasking motion video game. Conf. Hum. Factors Comput. Syst. - Proc. Part F1276, 2017–2024 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1145/3027063.3053105.

Wang, X., Niksirat, K.S., Silpasuwanchai, C., Wang, Z., Ren, X., Niu, Z.: How skill balancing impact the elderly player experience? Int. Conf. Signal Process. Proceedings, ICSP. 0, 983–988 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICSP.2016.7877976.

Pyae, A., Raitoharju, R., Luimula, M., Pitkäkangas, P., Smed, J.: Serious games and active healthy ageing: A pilot usability testing of existing games. Int. J. Netw. Virtual Organ. 16, 103–120 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1504/IJNVO.2016.075129

Mol, A.M., Silva, R.S., Ishitani, L.: Design recommendations for the development of virtual reality focusing on the elderly. Iber. Conf. Inf. Syst. Technol. Cist. 2019-June, 19–22 (2019). https://doi.org/10.23919/CISTI.2019.8760890.

Kari, T.: Exergaming experiences of older adults: A critical incident study. 32nd Bled eConference Humaniz. Technol. a Sustain. Soc. BLED 2019 - Conf. Proc. 639–654 (2020). https://doi.org/10.18690/978-961-286-280-0.34.

Broady, T., Chan, A., Caputi, P.: Comparison of older and younger adults’ attitudes towards and abilities with computers: Implications for training and learning. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 41, 473–485 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2008.00914.x

McLaughlin, A., Gandy, M., Allaire, J., Whitlock, L.: Putting fun into video games for older adults. Ergon. Des. 20, 13–22 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1177/1064804611435654

Eggenberger, P., Wolf, M., Schumann, M., de Bruin, E.D.: Exergame and balance training modulate prefrontal brain activity during walking and enhance executive function in older adults. Front. Aging Neurosci. 8, 1–16 (2016). https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2016.00066

Gorsic, M., Tran, M.H., Novak, D.: Cooperative Cooking: A Novel Virtual Environment for Upper Limb Rehabilitation. Proc. Annu. Int. Conf. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc. EMBS. 2018-July, 3602–3605 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1109/EMBC.2018.8513005.

Pyae, A., Joelsson, T., Saarenpää, T., Mika, L., Kattimeri, C., Pitkäkangas, P., Granholm, P., Smed, J.: Lessons Learned from Two Usability Studies of Digital Skiing Game with Elderly People in Finland and Japan. Int. J. Serious Games. 4, 37–52 (2017). https://doi.org/10.17083/ijsg.v4i4.183.

Jeremic, J., Zhang, F., Kaufman, D.: Older Adults’ perceptions about commercially available xbox kinect exergames. Springer International Publishing (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-22012-9_14

Borrego, G., Morán, A.L., Meza, V., Orihuela-Espina, F., Sucar, L.E.: Key factors that influence the UX of a dual-player game for the cognitive stimulation and motor rehabilitation of older adults. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10209-020-00746-3

Zhou, J., Salvendy, G.: Human aspects of IT for the aged population applications, services and contexts: Third international conference, ITAP 2017 held as part of HCI international 2017 vancouver, BC, Canada, july 9–14, 2017 proceedings, Part II. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. (including Subser. Lect. Notes Artif. Intell. Lect. Notes Bioinformatics). 10298, 217–227 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-58536-9.

Syed-Abdul, S., Malwade, S., Nursetyo, A.A., Sood, M., Bhatia, M., Barsasella, D., Liu, M.F., Chang, C.C., Srinivasan, K., Raja, M., Li, Y.C.J.: Virtual reality among the elderly: A usefulness and acceptance study from Taiwan. BMC Geriatr. 19, 1–11 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-019-1218-8

Hwang, M.Y., Hong, J.C., Hao, Y. wei, Jong, J.T.: Elders’ usability, dependability, and flow experiences on embodied interactive video games. Educ. Gerontol. 37, 715–731 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1080/03601271003723636.

Hera, T.D. la, Loos, E., Simons, M., Blom, J.: Benefits and factors influencing the design of intergenerational digital games: A Systematic Literature Review. Soc. 2017, Vol. 7, Page 18. 7, 18 (2017). https://doi.org/10.3390/SOC7030018.

Gerling, K., Mandryk, R.: Designing video games for older adults and caregivers. (2014).

Khoo, E.T., Merritt, T., Cheok, A.D.: Designing physical and social intergenerational family entertainment. Interact. Comput. 21, 76–87 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intcom.2008.10.009

De Oliveira Santos, L.H., Okamoto, K., Funghetto, S.S., Cavalli, A.S., Hiragi, S., Yamamoto, G., Sugiyama, O., Castanho, C.D., Aoyama, T., Kuroda, T.: Effects of social interaction mechanics in pervasive games on the physical activity levels of older adults: Quasi-experimental study. JMIR Serious Games. 7, (2019). https://doi.org/10.2196/13962.

Lankes, M., Hagler, J., Gattringer, F., Stiglbauer, B.: InterPlayces: Results of an intergenerational games study. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. (including Subser. Lect. Notes Artif. Intell. Lect. Notes Bioinformatics). 10622 LNCS, 85–97 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-70111-0_8.

Goršič, M., Cikajlo, I., Goljar, N., Novak, D.: A multisession evaluation of an adaptive competitive arm rehabilitation game. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 14, 1–16 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12984-017-0336-9

Goršič, M., Cikajlo, I., Novak, D.: Competitive and cooperative arm rehabilitation games played by a patient and unimpaired person: effects on motivation and exercise intensity. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 14, 1–18 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12984-017-0231-4

Buchem, I., Merceron, A., Kreutel, J., Haesner, M., Steinert, A.: Gamification designs in Wearable enhanced learning for healthy ageing. Proc. 2015 Int. Conf. Interact. Mob. Commun. Technol. Learn. IMCL 2015. 9–15 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1109/IMCTL.2015.7359545.

Seaborn, K., Fels, D.I.: Gamification in theory and action: A survey. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 74, 14–31 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2014.09.006

Ni, P.: 5 Ways to Motivate and Encourage Seniors. https://www.Psychologytoday.Com/Us/Blog/Communication-Success/201503/5-Ways-Motivate-and-Encourage-Seniors. 1–5 (2015).

Pan, Z., Miao, C., Yu, H., Leung, C., Chin, J.J.: The effects of familiarity design on the adoption of wellness games by the elderly. Proc. - 2015 IEEE/WIC/ACM Int. Jt. Conf. Web Intell. Intell. Agent Technol. WI-IAT 2015. 2, 387–390 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1109/WI-IAT.2015.198.

Ferreira, S.M., Sayago, S., Blat, J.: Towards iTV services for older people: Exploring their interactions with online video portals in different cultural backgrounds. Technol. Disabil. 26, 199–209 (2014). https://doi.org/10.3233/TAD-140419

Yang, Y.C.: Role-play in virtual reality game for the senior. ACM Int. Conf. Proceeding Ser. Part F1483, 31–35 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1145/3323771.3323812

Zhang, H., Wu, Q., Miao, C., Shen, Z., Leung, C.: Towards Age-friendly Exergame Design: The role of familiarity. CHI Play 2019 - Proc. Annu. Symp. Comput. Interact. Play. 45–57 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1145/3311350.3347191.

Zhang, H., Miao, C., Wang, D.: Familiarity design in exergames for elderly. Int. J. Inf. Technol. 22, 1–19 (2016)

Blocker, K.A., Wright, T.J., Boot, W.R.: Gaming preferences of aging generations. Gerontechnology. 12, 174–184 (2014). https://doi.org/10.4017/gt.2014.12.3.008.00

ESA ‘Entertainment Software Association’: 2019 ESSENTIAL FACTS About the Computer and Video Game Industry. (2019).

Kappen, D.L., Orji, R.: Gamified and persuasive systems as behavior change agents for health and wellness. XRDS Crossroads, ACM Mag. Students. 24, 52–55 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1145/3123750.

Rice, M., Koh, R., Liu, Q., He, Q., Wan, M., Yeo, V., Ng, J., Tan, W.P.: Comparing Avatar Game Representation Preferences across Three Age Groups. Conf. Hum. Factors Comput. Syst. - Proc. 2013-April, 1161–1166 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1145/2468356.2468564.

Kayama, H., Okamoto, K., Nishiguchi, S., Nagai, K., Yamada, M., Aoyama, T.: Concept software based on kinect for assessing dual-task ability of elderly people. Games Health J. 1, 348–352 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1089/g4h.2012.0019

Pyae, A., Luimula, M., Smed, J.: Investigating the usability of interactive physical activity games for elderly: A pilot study. 6th IEEE Conf. Cogn. Infocommunications, CogInfoCom 2015 - Proc. 185–193 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1109/CogInfoCom.2015.7390588.

Xu, W., Liang, H.N., Zhang, Z., Baghaei, N.: Studying the effect of display type and viewing perspective on user experience in virtual reality exergames. Games Health J. 9, 405–414 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1089/g4h.2019.0102

Boyle, E.A., Connolly, T.M., Hainey, T., Boyle, J.M.: Engagement in digital entertainment games: A systematic review. Comput. Human Behav. 28, 771–780 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2011.11.020

Carr, D.: Play and pleasure. Comput. Games Text Narrat. Play. Polity Press, UK Cambridge (2006)

Quiñones, D., Rusu, C., Rusu, V.: A methodology to develop usability/user experience heuristics. Comput. Stand. Interfaces. 59, 109–129 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csi.2018.03.002

Acknowledgements

This work has been supported by the PERGAMEX ACTIVE project, Ref. RTI2018-096986-B-C32, funded by the Ministry of Science and Innovation (MCI/AEI/FEDER, UE). We would like to thank the different expert evaluators who participated in the heuristic validation of this model from the Universidad Pontificia Católica de Valparaiso—Chile, Universidad de Granada—Spain, Universidad de Caldas—Colombia, Universidad de la Frontera—Chile, Universidad de Medellín—Colombia, Universidad Antonio José Camacho—Colombia and Universidad San Buenaventura—Colombia. Finally, we would like to thank MINCIENCIAS of government of Colombia for providing the necessary resources for the completion of this research.

Funding

This work was supported by PERGAMEX ACTIVE project, Ref. RTI2018-096986-B-C32, funded by the Ministry of Science and Innovation (MCI/AEI/FEDER, UE).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix A

Original evaluation questionnaire used by the different evaluators. This questionnaire is available in: https://bit.ly/3BwdxqY

Appendix B

Heuristic specification defined from the results and comments of the evaluators. This heuristics specification is available in: https://bit.ly/3QRj8xL

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Cardona, J.S., Lopez, J.A., Vela, F.L.G. et al. Meaningful learning: motivations of older adults in serious games. Univ Access Inf Soc (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10209-023-00987-y

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10209-023-00987-y