Abstract

Environmental stress is a major factor structuring communities. An environmental stress model (ESM) predicts that overall species richness and diversity should follow a unimodal trend along the full stress gradient along which assemblages from a regional biota can occur (not to be confused with the intermediate disturbance hypothesis, which makes predictions only for basal species along an intermediate-to-high stress range). Past studies could only provide partial support for ESM predictions because of the limited stress range surveyed or a low sampling resolution. In this study, we measured overall species richness and diversity (considering all seaweeds and invertebrates) along the intertidal elevation gradient on two wave-sheltered rocky shores from Helgoland Island, on the NE Atlantic coast. In intertidal habitats, tides cause a pronounced gradient of increasing stress from low to high elevations. We surveyed up to nine contiguous elevation zones between the lowest intertidal elevation (low stress) and the high intertidal boundary (high stress). Nonlinear regression analyses revealed that overall species richness and diversity followed unimodal trends across elevations on the two studied shores. Therefore, our study suggests that the ESM might constitute a useful tool to predict local richness and diversity as a function of environmental stress. Performing tests on other systems (marine as well as terrestrial) should help to refine the model.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A central goal of ecology is to understand the factors that determine biodiversity. Biodiversity has been studied commonly in terms of species richness and diversity. Richness is the number of species in a community, whereas diversity is a measure of how likely two individuals selected at random from the community belong to different species (Krebs 1999). Both traits are important because they are often related to ecological stability and functioning (Hooper et al. 2005; Stachowicz et al. 2007; Gamfeldt and Hillebrand 2008; García and Martínez 2012).

Environmental stress is the negative forcing that the abiotic environment exerts on the performance of organisms, and it affects species richness and diversity mediated by interspecific interactions (Menge et al. 2002; Crain and Bertness 2006). Based on marine benthic research, an environmental stress model (ESM) predicts how the richness and diversity of primary-space holders (also termed basal species) should vary along the full stress gradient along which assemblages from a regional biota can occur (Menge and Sutherland 1987). On marine rocky shores, primary-space holders are the sessile species attached to the substrate (seaweeds and filter-feeding invertebrates). This model predicts that the richness and diversity of primary-space holders should follow a bimodal curve when competitive exclusion occurs at intermediate stress levels or a unimodal curve when niche partitioning occurs at such stress levels. In the bimodal curve, the unimodal half from low to intermediate stress represents the predation hypothesis, whereas the unimodal half from intermediate to high stress represents the intermediate disturbance hypothesis (Menge and Sutherland 1987). Such richness and diversity curves result from changes in the relative importance of interspecific interactions (competition, herbivory, and predation) along the stress gradient (Menge and Sutherland 1987).

A later ESM version incorporated facilitation and made predictions for secondary species, which include secondary-space holders (sessile species attached to the primary-space holders) and the associated mobile species (Bruno et al. 2003). That ESM considers that the primary-space holders that competitively exclude other basal species at intermediate stress levels often increase habitat complexity through their bodies, favouring the occurrence of many secondary species, which peak in richness at such stress levels. Although not specified in Bruno et al. (2003), even when the curve for primary-space holders is unimodal (due to niche partitioning at intermediate stress levels), a unimodal curve should also result for secondary species, since neither consumer pressure nor abiotic stress is too high in the middle of the stress gradient.

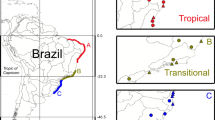

Ultimately, those ESM versions were combined to produce an ESM for overall species richness and diversity, that is, for basal and secondary species considered together. This ESM predicts that overall richness and diversity should follow a unimodal trend along the full stress gradient along which assemblages from a regional biota can occur (Scrosati and Heaven 2007; Fig. 1). This model should not be confused with the intermediate disturbance hypothesis (IDH), because the IDH curve (also unimodal) makes predictions only for primary-space holders and only between the intermediate and high levels of stress considered by the ESM (Menge and Sutherland 1987).

Environmental stress model for overall species richness and diversity. The thick horizontal line indicates the stress range likely occurring across intertidal elevations on wave-sheltered shores in Helgoland, relative to the full stress gradient along which assemblages from the NE Atlantic cold-temperate biota can occur. High stress is expected at high elevations, whereas low stress is expected at low elevations. The dotted sections indicate possible local variation among shores

ESM predictions on overall species richness and diversity have been tested in rocky intertidal habitats, which are the coastal areas occurring between the highest and lowest tides. The first test was done in northern Nova Scotia, Canada (Scrosati and Heaven 2007). Rocky intertidal habitats exhibit a pronounced vertical gradient of increasing stress from low to high elevations. This gradient is caused by tides, as key ecological factors such as temperature and desiccation reach extreme values toward high elevations because of long aerial exposures (Raffaelli and Hawkins 1999; Menge and Branch 2001; Watt and Scrosati 2013). However, the full stress gradient that applies to a regional biota in the ESM is rarely found locally (Menge and Sutherland 1987). For instance, the shores of northern Nova Scotia are inhabited by species from the NW Atlantic cold-temperate biogeographic region, which extends from Newfoundland, Canada, to Cape Hatteras, Unites States (Searles 1984; Adey and Hayek 2005). However, in northern Nova Scotia, cold stress during winter low tides is higher than on shores from the geographic center of this range, which in turn exhibit lower levels of heat stress than shores farther south within this range (Jones et al. 2010; Tam and Scrosati 2011). In addition, disturbance of intertidal habitats by winter sea ice is common in northern Nova Scotia (annually on the Gulf of St. Lawrence coast and sporadically on the open Atlantic coast; Scrosati and Heaven 2006; Tam and Scrosati 2011). Thus, the Nova Scotia study surveyed approximately only intermediate-to-high stress levels for the NW Atlantic cold-temperate intertidal biota. Accordingly, overall species richness and diversity generally increased from high to low intertidal elevations in northern Nova Scotia (Scrosati and Heaven 2007), supporting ESM predictions. To test ESM predictions for lower stress levels, surveying more benign conditions for a regional biota was deemed necessary.

Thus, a study was carried out in rocky intertidal habitats from Helgoland Island, on the North Sea off mainland Germany (Scrosati et al. 2011). The NE Atlantic coast also exhibits a cold-temperate intertidal biota, which occurs between northern Norway and the northwestern coast of the Iberian Peninsula. The northern boundary of this biota is mainly determined by cold stress, while the southern boundary is determined by heat stress (Lüning 1990; Wethey et al. 2011). Helgoland is located near the center of this biogeographic range, so its shores experience relatively benign (neither too cold nor too hot) conditions. Thus, low stress levels for this regional biota should occur in Helgoland at low intertidal elevations (because of short emersion times) on wave-sheltered shores (because of low wave action), while high stress levels occur at high elevations due to long aerial exposures. In other words, vertical intertidal gradients on Helgoland’s sheltered shores offer the possibility to survey a wide range of stress that includes the intermediate stress level considered by the ESM (Fig. 1).

To test ESM predictions, the study by Scrosati et al. (2011) in Helgoland divided the intertidal range between chart datum and the high intertidal boundary into three elevation zones (high, middle, and low). Mean overall richness did follow a unimodal trend but, although richness significantly increased from the high zone to the middle zone, differences between the middle zone and the low zone were not significant, thus failing to fully support ESM predictions. That trend, nonetheless, suggested that increasing the spatial resolution of sampling might statistically reveal a unimodal pattern, as predicted by the ESM (Scrosati et al. 2011). Therefore, the present study investigates trends in overall richness and diversity along vertical intertidal gradients on Helgoland’s sheltered shores using a higher degree of spatial resolution. To further improve the new test, we surveyed a wider intertidal range than before, by sampling habitats occurring below chart datum but still above the lowest tide mark, indicating that such elevations are also intertidal. According to the ESM (Fig. 1), our hypotheses were that overall species richness and diversity would exhibit a unimodal trend along the intertidal elevation gradient.

Materials and methods

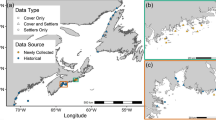

We surveyed two rocky shores on Helgoland Island: Nord-Ost Hafen (54°11′00″N, 7°53′34″E) and Kringel (54°10′60″N, 7°53′15″E; Fig. 2). Maximum water velocity (an index of wave exposure) was measured with spring-loaded dynamometers (see design in Bell and Denny 1994) between September 2009 and November 2011, yielding values of 1.7 ± 0.1 m s−1 (mean ± SE, n = 212, range = 1.1–2.6 m s−1) for Nord-Ost Hafen and 2.8 ± 0.1 m s−1 (n = 206, range = 1.4–4.8 m s−1) for Kringel (Lesniowski 2010, M. Molis, unpublished data). Thus, both shores are wave-sheltered, since values of maximum water velocity on coasts facing the open ocean in the North Atlantic reach 12 m s−1 (Hunt and Scheibling 2001). The substrate is granitic at Nord-Ost Hafen and a mixture of sandstone and concrete at Kringel.

To determine the richness and diversity trends across elevations, we divided the intertidal range into elevation zones. At Nord-Ost Hafen, the full intertidal range between the elevation of the lowest tide (−10 cm, relative to chart datum) and the highest elevation exhibiting sessile perennial organisms (the seaweed Fucus spiralis) was 2.6 m. Thus, we divided the intertidal range of Nord-Ost Hafen into nine elevation zones of 30 cm in vertical extent each one. At Kringel, the upper elevations had been altered shortly before our study because of construction, which resulted in such elevations consisting in new substrate that was mostly bare at the time of our survey. Thus, at Kringel, we sampled a smaller intertidal range, between the elevation of the lowest tide and an elevation of 1.7 m, which represented the range that exhibited pristine communities. We divided such a range into six elevation zones, each zone being 30 cm in vertical extent. We determined elevations using tide tables and a theodolite with a precision of 1 cm, indicating the boundaries between elevation zones in the field using metallic markers bolted to the rocky substrate.

At each elevation zone on each shore, we determined species richness and diversity for 12–13 replicate quadrats (30 cm × 30 cm) that were randomly placed following the coastline. In May–June 2010, we measured during low tides the percent cover of each algal and invertebrate species (>1 mm) found in the quadrats, using a sampling frame that was divided in 100 squares with monofilament line. If a species covered less than 1 % of the entire quadrat, we recorded its percent cover as 0.5 %. For each quadrat, we firstly took cover data for the canopy layer, then for the understory turf layer, and finally for the crustose layer. Thus, the sum of percent cover values for the different species present in any quadrat could exceed 100 %. We used field guides and taxonomic keys (Kornmann and Sahling 1977, 1994; Burrows 1991; Maggs and Hommersand 1993; Irvine and Chamberlain 1994; Stresemann 1994; Hayward and Ryland 1995; Brodie et al. 2007) for identifications. Organisms were identified to the species level or, for small species that looked very similar, to the lowest possible taxonomic level, as usually done in studies that survey all producers and consumers in communities (Kimbro and Grosholz 2006; Russell et al. 2006; Valdivia and Molis 2009). We measured percent cover to quantify species abundance because alternative measures of abundance (e.g., density of individuals) cannot always be determined reliably for clonal species (Scrosati 2005) or (e.g., biomass) would have required destructive sampling, which we avoided to minimize impact. Additionally, abundance was measured using the same metric for all species because that is a requirement to calculate diversity indices (Magurran 2004).

For each quadrat, we determined species richness (S) as the number of species found therein and calculated species diversity using the Shannon index (H′):

where p i was the proportional abundance of species i in the quadrat, that is, that species’ percent cover divided by the sum of percent cover values for all species in the quadrat (Magurran 2004). Given that the ESM predicted unimodal trends in richness and diversity along the elevation gradient, we did quadratic regression analyses separately for richness and diversity for the two studied shores. We calculated the parameters of the four quadratic equations through nonlinear least-squares regression (Quinn and Keough 2002). Before doing the regressions, we evaluated the possible existence of outliers by studying box plots for each elevation zone and data set, as a result of which we eliminated one extreme value of diversity for Kringel because it would otherwise have made pattern detection in the data difficult (Quinn and Keough 2002). We did the analyses with SYSTAT 5.2 for Macintosh (Wilkinson et al. 1992).

Results

We found 79 species in total, including 40 macroalgae and 39 invertebrates (Tables 1, 2). Nord-Ost Hafen had 69 species (36 macroalgae and 33 invertebrates), while Kringel had 61 species (29 macroalgae and 32 invertebrates). Eighteen species were only found at Nord-Ost Hafen (11 macroalgae and 7 invertebrates), while 10 species were only found at Kringel (6 macroalgae and 4 invertebrates).

Overall species richness followed a significant unimodal (quadratic) trend along the vertical intertidal gradient on the two studied shores, peaking at a relatively low elevation (Fig. 3). Overall species diversity also exhibited a significant unimodal pattern across intertidal elevations on the two studied shores and also peaked at a relatively low elevation (Fig. 3). The results of the four regression analyses are summarized in Table 3, where 95 % confidence intervals indicate that all four quadratic terms were significant, as the intervals did not include zero under a significance level of 0.05.

Trends in overall species richness (a, b) and diversity (c, d) along the vertical intertidal gradient at Nord-Ost Hafen and Kringel, respectively. At Nord-Ost Hafen, surveys were carried out at elevation zones 1 (between −10 cm and 20 cm of elevation relative to chart datum), 2 (20–50 cm), 3 (50–80 cm), 4 (80–110 cm), 5 (110–140 cm), 6 (140–170 cm), 7 (170–200 cm), 8 (200–230 cm), and 9 (230–260 cm). At Kringel, only elevation zones 1–6 were surveyed (see “Materials and Methods” for explanation). The quadratic function of best fit is shown for each relationship (see “Results” for statistics)

Discussion

The ESM has correctly predicted a unimodal trend for overall species richness and diversity along intertidal elevation gradients in Helgoland. Previous studies could only offer partial support for such predictions because of the limited range of environmental stress available for testing (Scrosati and Heaven 2007) or the coarse sampling resolution employed (Scrosati et al. 2011). By using a high spatial resolution to sample the vertical intertidal range on shores far away from the extreme cold and heat stresses that limit the biogeographic distribution of cold-temperate species, our study provides for the first time the evidence of the existence of unimodal trends in overall richness and diversity along environmental stress gradients, as predicted by the ESM.

Interestingly, overall richness and diversity followed a similar trend across intertidal elevations. Despite both variables being different (albeit related), they have often been used interchangeably in ecology (Whittaker et al. 2001; Wilsey et al. 2005; Stachowicz et al. 2007). However, sometimes they may show different trends across environmentally different habitats (Kimbro and Grosholz 2006; Scrosati and Heaven 2007; Wilsey and Stirling 2007). Although the factors that may prompt trend decoupling remain not fully understood, our results support the notion that richness and diversity may indeed be predictable from one another in some natural systems.

The trend in overall richness and diversity predicted by the ESM (Scrosati and Heaven 2007) results from changes in the relative importance of species interactions along stress gradients (Menge and Sutherland 1987; Bruno et al. 2003). Thus, it is worth discussing our species abundance data in search of possible mechanisms underlying the observed patterns in richness and diversity. Firstly, we note that the combined cover of all species was lowest at the two highest elevation zones on both studied shores (see “relevant group information” in Tables 1, 2). Such results agree with the ESM prediction that species performance (and ultimately richness) should be limited largely by abiotic stress in very stressful habitats (Menge and Sutherland 1987).

At Kringel, the peaks in overall richness and diversity occurred at a similar elevation at which the combined cover of canopy-forming algae (Fucus spp., Mastocarpus stellatus, and Chondrus crispus) peaked (see “relevant group information” in Table 2). Intertidal algal canopies provide shelter, substrate, and food for many species (Bertness et al. 1999; Figueiredo et al. 2000; Bruno and Bertness 2001). Thus, those macroalgae could be playing an important role in determining the peaks in richness and diversity. These dominant seaweeds coexisted along a wide elevational range, without any basal species monopolizing any elevation zone. Thus, these results lend support to the ESM version based on niche diversification among primary-space holders (Menge and Sutherland 1987), which seems to enhance overall richness when these algae become most abundant. At Nord-Ost Hafen, the combined cover of Fucus spp., M. stellatus, and C. crispus remained similarly high along a wider elevational range (see “relevant group information” in Table 1) than at Kringel, the lower boundary of this range occurring near the elevation where richness and diversity peaked. The cover of Fucus spp. did peak approximately where richness and diversity were highest. M. stellatus was most abundant at higher elevations, but the higher stress levels expected at such places may have limited the ability of this alga to enhance local richness. Studies on the potentially different ability of these canopy-forming seaweeds to enhance local richness as a function of abiotic stress should clarify their relative contribution in this sense.

Consumers may also be relevant players in structuring communities. On North Atlantic rocky shores, periwinkles (Littorina spp.) are important grazers (Watson and Norton 1981; Janke 1990; Lauzon-Guay and Scheibling 2009) and can also remove invertebrate recruits through bulldozing (Buschbaum 2000). At Kringel, the abundance of Littorina spp. increased from high to low elevations, which agrees with the ESM expectation that consumer pressure should increase as stress decreases (Menge and Sutherland 1987). At Nord-Ost Hafen, periwinkle abundance remained similar across elevations and was lower than at Kringel, which suggests a weaker grazing role at Nord-Ost Hafen. Dogwhelks (Nucella lapillus) and green crabs (Carcinus maenas) are important predators on North Atlantic rocky shores (Ropes 1968; Menge 1976; Eschweiler et al. 2009; Wong et al. 2012). At Kringel, both species increased in abundance toward low elevations, which also agrees with the ESM expectation of an increasing consumer pressure with decreasing stress (Menge and Sutherland 1987). However, at Nord-Ost Hafen, dogwhelks were absent and crabs were rare. Thus, although data on consumer abundance alone may not predict consumer pressure accurately (Menge 1978), our data seem to support ESM expectations on consumers for Kringel, but remain unclear for Nord-Ost Hafen. Clearly, the links between interspecific interactions and the elevational trends in species richness and diversity in Helgoland need to be determined experimentally.

Recent studies confirm that human activities are causing biodiversity losses globally, with negative consequences for ecosystem services (Cardinale et al. 2012; Hooper et al. 2012). Thus, renewed calls are being made to reduce anthropogenic impacts (Peh and Lewis 2012). To accurately evaluate the magnitude of such impacts across space and time, being able to predict local species richness and diversity as a function of environmental stress would be useful. Our study indicates that the ESM may be a valuable tool for such a purpose. To refine the model and increase its predicting ability, extending model testing to other seashores and adapting predictions for other systems (marine as well as terrestrial) should be a useful undertaking.

References

Adey WH, Hayek LC (2005) The biogeographic structure of the western North Atlantic rocky intertidal. Cryptogamie, Algol 26:35–66

Bell EC, Denny MW (1994) Quantifying “wave exposure”: a simple device for recording maximum velocity and results of its use at several field sites. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 181:9–29

Bertness MD, Leonard GH, Levine JM, Schmidt PR, Ingraham AO (1999) Testing the relative contribution of positive and negative interactions in rocky intertidal communities. Ecology 80:2711–2726

Brodie J, Maggs CA, John DM (2007) Green seaweeds of Britain and Ireland. British Phycological Society, London

Bruno JF, Bertness MD (2001) Habitat modification and facilitation in benthic marine communities. In: Bertness MD, Gaines SD, Hay ME (eds) Marine community ecology. Sinauer, Sunderland, pp 201–218

Bruno JF, Stachowicz JJ, Bertness MD (2003) Inclusion of facilitation into ecological theory. Trends Ecol Evol 18:119–125

Burrows EM (1991) Seaweeds of the British Isles, vol 2. Chlorophyta, British Museum (Natural History), London

Buschbaum C (2000) Direct and indirect effects of Littorina littorea (L.) on barnacles growing on mussel beds in the Wadden Sea. Hydrobiologia 440:119–128

Cardinale BJ, Duffy JE, González A, Hooper DU, Perrings C, Venail P, Narwani A, Mace GM, Tilman D, Wardle DA, Kinzig AP, Daily GC, Loreau M, Grace JB, Larigauderie A, Srivastava DS, Naeem S (2012) Biodiversity loss and its impact on humanity. Nature 486:59–67

Crain CM, Bertness MD (2006) Ecosystem engineering across environmental gradients: implications for conservation and management. Bioscience 56:211–218

Eschweiler N, Molis M, Buschbaum C (2009) Habitat-specific size structure variations in periwinkle populations (Littorina littorea) caused by biotic factors. Helgol Mar Res 63:119–127

Figueiredo MA, Kain JM, Norton TA (2000) Responses of crustose corallines to epiphyte and canopy cover. J Phycol 36:17–24

Gamfeldt L, Hillebrand H (2008) Biodiversity effects on aquatic ecosystem functioning—maturation of a new paradigm. Int Rev Hydrobiol 93:550–564

García D, Martínez D (2012) Species richness matters for the quality of ecosystem services: a test using seed dispersal by frugivorous birds. Proc R Soc B 279:3106–3113

Hayward PJ, Ryland JS (1995) Handbook of the marine fauna of north-west Europe. Oxford University Press, New York

Hooper DU, Chapin FS, Ewel JJ, Hector A, Inchausti P, Lavorel S, Lawton JH, Lodge DM, Loreau M, Naeem S, Schmid B, Setälä H, Symstad AJ, Vandermeer J, Wardle DA (2005) Effects of biodiversity on ecosystem functioning: a consensus of current knowledge. Ecol Monogr 75:3–35

Hooper DU, Adair EC, Cardinale BJ, Byrnes JEK, Hungate BA, Matulich KL, González A, Duffy JE, Gamfeldt L, O’Connor MI (2012) A global synthesis reveals biodiversity loss as a major driver of ecosystem change. Nature 486:105–108

Hunt HL, Scheibling RE (2001) Patch dynamics of mussels on rocky shores: integrating process to understand pattern. Ecology 82:3213–3231

Irvine LM, Chamberlain YM (1994) Seaweeds of the British Isles, Volume 1 Rhodophyta, Part 2B Corallinales. Hildenbrandiales, British Museum (Natural History), London

Janke K (1990) Biological interactions and their role in community structure in the rocky intertidal of Helgoland (German Bight, North Sea). Helgol Meeresunters 44:219–263

Jones SJ, Lima FP, Wethey DS (2010) Rising environmental temperatures and biogeography: poleward range contraction of the blue mussel, Mytilus edulis L., in the western Atlantic. J Biogeogr 37:2243–2259

Kimbro DL, Grosholz ED (2006) Disturbance influences oyster community richness and evenness, but not diversity. Ecology 87:2378–2388

Kornmann P, Sahling PH (1977) Meeresalgen von Helgoland: benthische Grün-, Braun- und Rotalgen. Helgol Meeresunters 29:1–289

Kornmann P, Sahling PH (1994) Meeresalgen von Helgoland: zweite Ergänzung. Helgol Meeresunters 48:365–406

Krebs CJ (1999) Ecological methodology. Benjamin Cummings, Menlo Park

Lauzon-Guay JS, Scheibling RE (2009) Food-dependent movement of periwinkles (Littorina littorea) associated with feeding fronts. J Shellfish Res 28:581–587

Lesniowski T (2010) Modulation trophischer Interaktionen zwischen Mesoherbivoren und Makroalgen durch abiotische Stressoren. Ruhr Universität, Dissertation

Lüning K (1990) Seaweeds. Their environment, biogeography, and ecophysiology. John Wiley & Sons, New York

Maggs CA, Hommersand MH (1993) Seaweeds of the British Isles: Volume 1 Rhodophyta, Part 3A Ceramiales. The Natural History Museum, London

Magurran AE (2004) Measuring biological diversity. Blackwell Publishing, London

Menge BA (1976) Organization of the New England rocky intertidal community: role of predation, competition, and environmental heterogeneity. Ecol Monogr 46:355–393

Menge BA (1978) Predation intensity in a rocky intertidal community: effect of an algal canopy, wave action, and desiccation on predator feeding rates. Oecologia 34:17–35

Menge BA, Branch GM (2001) Rocky intertidal communities. In: Bertness MD, Gaines SD, Hay ME (eds) Marine community ecology. Sinauer, Sunderland, pp 221–251

Menge BA, Sutherland JP (1987) Community regulation: variation in disturbance, competition, and predation in relation to environmental stress and recruitment. Am Nat 130:730–757

Menge BA, Olson AM, Dahlhoff EP (2002) Environmental stress, bottom-up effects, and community dynamics: integrating molecular-physiological and ecological approaches. Integr Comp Biol 42:892–908

Peh KSH, Lewis SL (2012) Conservation implications of recent advances in biodiversity—functioning research. Biol Conserv 151:26–31

Quinn GP, Keough MJ (2002) Experimental design and data analysis for biologists. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Raffaelli D, Hawkins S (1999) Intertidal ecology. Chapman & Hall, London

Ropes JW (1968) The feeding habits of the green crab, Carcinus maenas (L.). US Fish Wildl Serv Fish Bull 67:183–203

Russell R, Wood SA, Allison G, Menge BA (2006) Scale, environment, and trophic status: the context dependency of community saturation in rocky intertidal communities. Am Nat 167:E158–E170

Scrosati R (2005) Review of studies on biomass-density relationships (including self-thinning lines) in seaweeds: main contributions and persisting misconceptions. Phycol Res 53:224–233

Scrosati R, Heaven C (2006) Field technique to quantify intensity of scouring by sea ice in rocky intertidal habitats. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 320:293–295

Scrosati R, Heaven C (2007) Spatial trends in community richness, diversity, and evenness across rocky intertidal environmental stress gradients in eastern Canada. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 342:1–14

Scrosati RA, Knox AS, Valdivia N, Molis M (2011) Species richness and diversity across rocky intertidal elevation gradients in Helgoland: testing predictions from an environmental stress model. Helgol Mar Res 65:91–102

Searles RB (1984) Seaweed biogeography of the mid-Atlantic coast of the United States. Helgol Meeresunters 38:259–271

Stachowicz JJ, Bruno JF, Duffy JE (2007) Understanding the effects of marine biodiversity on communities and ecosystems. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst 38:739–766

Stresemann E (1994) Exkursionsfauna von Deutschland, Band 1: Wirbellose (ohne Insekten). Spektrum Akademischer Verlag, Berlin

Tam JC, Scrosati RA (2011) Mussel and dogwhelk distribution along the northwest Atlantic coast: testing predictions derived from the abundant-centre model. J Biogeogr 38:1536–1545

Valdivia N, Molis M (2009) Observational evidence of a negative biodiversity–stability relationship in intertidal epibenthic communities. Aquat Biol 4:263–271

Watson DC, Norton TA (1981) The habitat and feeding preferences of Littorina obtusata (L.) and L. mariae Sacchi et Rastelli. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 112:61–72

Watt CA, Scrosati RA (2013) Bioengineer effects on understory species richness, diversity, and composition change along an environmental stress gradient: experimental and mensurative evidence. Estuar, Coast Shelf Sci, in press. doi:10.1016/j.ecss.2013.02.006

Wethey DS, Woodin SA, Hilbish TJ, Jones SJ, Lima FP, Brannock PM (2011) Response of intertidal populations to climate: effects of extreme events versus long-term change. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 400:132–144

Whittaker RJ, Willis KJ, Field R (2001) Scale and species richness: towards a general, hierarchical theory of species diversity. J Biogeogr 28:453–470

Wilkinson L, Hill MA, Vang E (1992) SYSTAT: Statistics, Version 5.2 Edition. SYSTAT, Evanston

Wilsey B, Stirling G (2007) Species richness and evenness respond in a different manner to propagule density in developing prairie microcosm communities. Plant Ecol 190:259–273

Wilsey BJ, Chalcraft DR, Bowles CM, Willig MR (2005) Relationships among indices suggest that richness is an incomplete surrogate for grassland biodiversity. Ecology 86:1178–1184

Wong MC, d’Entremont J, Barbeau MA (2012) An approach for quantifying effects of multiple predators that forage on different time scales. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 420–421:100–109

Acknowledgments

We thank an anonymous reviewer for providing constructive comments on the manuscript. Our research was supported by funds awarded to MM by Biologische Anstalt Helgoland (Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research, AWI) and by grants awarded to RAS by the Canada Research Chairs (CRC) program, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC, Discovery Grant), and the Canada Foundation for Innovation (CFI).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by L. Giménez.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zwerschke, N., Bollen, M., Molis, M. et al. An environmental stress model correctly predicts unimodal trends in overall species richness and diversity along intertidal elevation gradients. Helgol Mar Res 67, 663–674 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10152-013-0352-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10152-013-0352-5