Abstract

Background

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) assessments are increasingly incorporated into oncological randomized controlled trials (RCTs). The quality of HRQoL reporting in RCTs concerning palliative systemic treatment for advanced esophagogastric cancer is currently unknown. Therefore, we conducted a systematic review to investigate the quality of HRQoL reporting over time.

Methods

PubMed, CENTRAL and EMBASE were searched for RCTs concerning systemic treatment for advanced esophagogastric cancer up to February 2017. The Minimum Standard Checklist for Evaluating HRQoL Outcomes in Cancer Clinical Trials was used to rate the quality of HRQoL reporting. Univariate and multivariate generalized linear regression analysis was used to investigate factors affecting the quality of reporting over time.

Results

In total, 37 original RCTs (N = 10,887 patients) were included. The quality of reporting was classified as ‘very limited’ in 4 studies (11%), ‘limited’ in 24 studies (65%), and ‘probably robust’ in 9 studies (24%). HRQoL reporting did not improve over time, and it did not improve following the publication of the CONSORT-PRO statement in 2013. The publication of HRQoL findings in a separate article and second-line treatment were associated with better reporting.

Conclusions

HRQoL reporting in RCTs concerning palliative systemic therapy for advanced esophagogastric cancer is limited and has not improved over time. This systematic review provides specific recommendations for authors to improve HRQoL reporting: formulate hypotheses a priori, clearly describe instrument administration, and handle missing data and interpret findings appropriately.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cancers of the esophagus and stomach are the second and sixth most common causes of cancer-related deaths worldwide [1]. Patients with unresectable locally advanced and metastatic disease can be offered palliative systemic treatment to prolong survival, to offer symptom relief, and to improve or maintain health-related quality of life (HRQoL) [2, 3].

Recognition of the importance of HRQoL is reflected in the fact that HRQoL is assessed in randomized clinical trials (RCTs) with increasing frequency. In the past decades, an increase in HRQoL assessments was shown of 3.6% of trials from all disciplines and 6.7% of cancer trials. However, considerable variation among these HRQoL assessments in the instruments used has been noted, and the reporting of methods and results has often been inadequate [4, 5]. Also, a more recent study has shown that even though more RCT reports are meeting the quality standards for HRQoL assessment, the analysis and reporting of data and the presentation of findings remain highly variable [6]. Inadequate reporting of HRQoL in clinical trials may lead to a loss of valuable information or may even mislead clinical decision-making [7].

In the field of oncological RCTs, Efficace and colleagues showed that the reporting of HRQoL in RCTs of high-incidence diseases (i.e., breast, colorectal, prostate, and lung cancers) has improved over the years [7]. In contrast, in the majority of studies investigating curative treatment for esophageal cancer (a disease with a low incidence), the reporting of HRQoL was limited [8]. The reporting of HRQoL in studies of palliative therapy for advanced esophagogastric cancer has not yet been investigated. Given the limited remaining life span of this patient group, an emphasis on HRQoL is paramount. Therefore, we systematically reviewed the literature to determine the quality of HRQoL reporting in RCTs that involve palliative systemic therapy for patients with esophagogastric cancer. The following research questions were formulated. (1) What is the quality of HRQoL outcome reporting in locally advanced esophagogastric cancer? (2) What aspects of HRQoL reporting require improvement in order to facilitate clinical decision-making? (3) Has the quality of HRQoL reporting improved over time? Given the increasing body of literature regarding patient-reported outcome research, we hypothesized that the reporting of HRQoL in unresectable locally advanced and metastatic esophagogastric cancer had improved over time.

Methods

The PRISMA statement guided the writing of the manuscript. We focused on items that are relevant to the research questions and excluded irrelevant ones (e.g., items related to potential bias with respect to treatment outcomes).

Search methods

The study protocol was not registered in advance. The online databases PubMed, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) as well as meeting abstracts from the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) were searched for RCTs on palliative systemic therapy for advanced esophagogastric cancer up to February 2017. Details regarding this search can be found in Online Resource 1 in the Electronic supplementary material (ESM). Prospective registration databases such as clinical trials.gov were not searched, as our aim was to assess published reports. For the same reason, no contact with study authors was sought for additional information. Titles, abstracts, and full texts were screened by EtV and NHM. Disagreements were discussed with JJvK until consensus was reached.

Study selection

Studies were included that met the following criteria: (1) prospective phase II or III RCT design; (2) unresectable, metastatic, or recurrent esophageal, gastroesophageal junction (GEJ), or gastric cancer; (3) palliative systemic therapy (i.e., chemotherapy and/or targeted therapy); (4) full-text articles published in English; and (5) HRQoL was measured with validated questionnaires. Studies using self-constructed nonvalidated HRQoL questionnaires were not eligible because of their nonreproducible nature or a lack of information regarding their psychometric properties.

Data extraction

Data extraction was conducted by EtV and JJvK using Microsoft Excel. The following baseline characteristics of the included studies and patients were extracted: number of patients enrolled in the study, gender, age, performance status, tumor histology, tumor location, and disease status. The following characteristics regarding HRQoL reporting were extracted: the presence of a hypothesis a priori, the rationale for the HRQoL instrument, psychometric properties, cultural validity, HRQoL domains, instrument administration, baseline compliance, timing of assessments, documentation of missing data, and the clinical significance and presentation of the results in the discussion section. The quality of HRQoL reporting in each article was rated using the Minimum Standard Checklist for Evaluating HRQoL Outcomes in Cancer Clinical Trials checklist [9]. Articles were rated independently by EtV and JJvK. Discrepancies were discussed until a consensus was reached. The checklist consists of eleven items that can be scored as ‘yes’ (one point) or ‘no’ (zero points), and contains four domains: conceptual, measurement, methodology, and interpretation. Two items (‘a priori hypothesis stated’ and ‘cultural validity verified’) could also be evaluated as ‘not applicable’ (N/A) if the study explicitly stated that the HRQoL assessment was intended for exploratory investigations only or if the HRQoL measure was validated in the same population as that of the trial. When RCTs used validated measures for their study population, all items in the measurement domain (i.e., ‘psychometric properties reported,’ ‘cultural validity verified,’ and ‘adequacy of domains covered’) were scored as ‘yes.’ Three mandatory items of the checklist are: ‘psychometric properties reported,’ ‘baseline compliance reported,’ and ‘reasons for missing data reported.’ The checklist classifies the HRQoL reporting into the following categories: ‘very limited’ (score 0–4), ‘limited’ (score 5–7 or ‘no’ on one or more of the mandatory items), and ‘probably robust’ (score 8–11 and ‘yes’ on all mandatory items). Studies classified as ‘probably robust’ are most likely to have an impact on clinical decision-making [9].

Statistical analysis

For statistical analysis, the quality of HRQoL reporting—our main outcome—was expressed as an adjusted checklist score (ACS). The ACS was calculated for each study report by dividing the raw item score by the total number of applicable items. Higher ACS scores imply better quality of reporting. Descriptive statistics were used to gain insight into the quality of reporting. To assess the extent to which the quality of HRQoL reporting has improved over time, the variance and change in the ACS over time was graphically assessed using a scatterplot. Subsequently, a univariate generalized linear regression analysis with a binomial distribution, a logit link function, and robust standard errors was performed. Herewith, the independent variable ‘time’ is expressed as the year of publication and the dependent variable ‘quality of HRQoL reporting’ is expressed as the ACS. Predicted values in our model can range between 0 and 1. In order to investigate other associations of study characteristics with the quality of HRQoL reporting, the following covariates were considered in the regression analysis: (1) whether or not the study reported statistically significant differences in HRQoL results at any scale between arms or within arms over time (no vs yes); (2) if a separate article with HRQoL results was published (no vs yes); (3) the presence of an appendix or supplementary data (no vs yes); (4) intention-to-treat sample size (continuous); (5) type of endpoint (primary vs secondary); and (6) type of therapy line (first vs second vs third). Furthermore, we investigated if there were differences in the median ACS between studies that were published before versus after the publication of the CONSORT-PRO statement [10] using the Mann–Whitney U test. Statistical significance was reached at the 5% level and all analyses were performed using STATA version 14 for Windows.

Results

Literature search

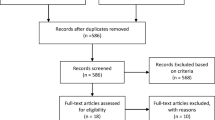

One hundred sixty-four RCTs investigating palliative systemic therapy for advanced esophagogastric cancer were eligible. Among these, 37 unique RCTs (N = 10,887 patients) reported on HRQoL [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56]. More details regarding the number of studies screened, assessed for eligibility, and included in the review can be found in Fig. 1. Eight studies (21.6%) published HRQoL findings separately. The year of publication of the studies ranged from 1997 to 2017. Major baseline characteristics of the included studies are shown in Table 1.

Checklist

Conceptual issues

Only nine studies (24.3%) reported an a priori hypothesis, and two studies (5.4%) stated explicitly that the HRQoL assessment had an exploratory nature. No studies provided a rationale for selecting a specific HRQoL questionnaire (see Table 2). Checklist scores per item per RCT are provided in Online Resource 2 in the ESM.

Measurement issues

All studies used a culturally validated HRQoL questionnaire with previously published psychometric properties and adequate covering of HRQoL domains. The most frequently used questionnaire was the EORTC QLQ-C30 (32 studies, 86.5%) (Table 1). Additional disease-specific questionnaires (e.g., EORTC QLQ-OES18 for esophageal cancer, STO22 for gastric cancer, or OG25 for esophagogastric cancer) were used in addition to the QLQ-C30 (as recommended by the EORTC) in 12 of the 37 studies (32.4%). Five studies (13.5%) used the EQ-5D, four of which were employed in combination with the EORTC QLQ-C30. The Spitzer Quality of Life Index (a proxy-based questionnaire) was used solely in one study (2.7%).

Methodology

In eight studies (21.6%), the authors specified by whom and in which clinical setting the HRQoL instrument was administered. Baseline compliance was reported in 30 studies (81.1%), and the timing schedule of the HRQoL assessments was documented in 36 studies (97.3%). Only 13 studies (35.1%) provided reasons for missing data or the number of patients for whom data were missing during the study.

HRQoL interpretation

In 15 studies (40.1%), the authors addressed the clinical significance of the HRQoL findings. In 22 studies (59.5%), the authors provided any comments on the HRQoL assessment in their study, regardless of the results.

Overall quality of HRQoL reporting

Among the 37 studies, the quality of 4 studies (10.8%) was classified as ‘very limited,’ that of 24 studies (64.9%) was classified as ‘limited,’ and the quality of 9 studies (24.3%) was classified as ‘probably robust.’ Figure 2 shows that the adjusted checklist scores per study varied over time. A high variability in ACS scores over time and also within publication years can be seen. For all studies, the median quality score was 0.55 and ranged from 0.27 to 0.91. Univariate generalized linear regression analysis showed that the year of publication was not associated with an increased ACS (β = 0.004, SE = 0.007, P = 0.57). Moreover, there was no difference between the median ACS scores of studies published before [median ACS = 0.55, interquartile range (IQR) = 0.5–0.64, N = 20) and after (median ACS = 0.55, IQR = 0.55–0.82, N = 17) the publication of the CONSORT-PRO statement, z = 1.12, P = 0.26. Second-line therapy and the publication of HRQoL results in a separate article were found to be significantly associated with the quality of reporting in the multivariate analysis (Table 3). In addition, post hoc analysis showed similar results when the criterion with the lowest score (’rationale for instrument reported’) was omitted (data not shown).

Discussion

Although more than half of all the RCTs included in this systematic review were published in the past 5 years, the quality of HRQoL reporting in esophagogastric cancer RCTs involving palliative systemic therapy was limited and did not improve over time. This outcome is independent of the type of endpoint used in the RCT, the usage of supplementary data or appendices in the main publication, and, most importantly, the number of patients in the RCT. The latter indicates that shortcomings in reporting occur in both small and large phase III RCTs. Since larger and otherwise methodologically sound trials are the basis for guideline development and clinical decision-making, we advocate that care should be taken when interpreting HRQoL findings from these trials.

While most included studies report the timing schedule of the HRQoL assessments, describe compliance rates, and use validated questionnaires, the following aspects of HRQoL reporting require improvement: the formulation of a priori hypotheses, a clear description of how the instrument is administered, the interpretation of findings, and the number of missing data as well as how such data are handled (see Table 2). The latter in particular provides valuable information regarding potential bias in HRQoL estimates when there is nonrandom attrition. The importance of reporting missing data is reflected in the checklist, given that it is required before the study can be rated as high quality.

RCTs that presented HRQoL findings in a separate article were significantly more likely to be of better quality than studies that published their HRQoL findings along with the main clinical results. This pattern was also found in the systematic review of Brundage and colleagues [6]. Those authors emphasized that poorer reporting is most likely due to restrictions on manuscript length. Thus, omitting valuable HRQoL data to ensure that the word count is below a particular limit might lead to reporting bias and therefore hamper interpretation and clinical decision-making. Furthermore, publication bias could arise when findings are not significant and/or compliance rates in RCTs are low. Conversely, the publication of HRQoL data separately from the main clinical findings may reduce their clinical impact. For these reasons, one could consider reporting HRQoL findings in an extensive appendix or supplementary dataset along with the main article, so that valuable information regarding both clinical and HRQoL outcomes can be presented within one publication.

As observed previously, we found substantial variability in the quality of HRQoL reporting [4, 6, 7, 57]. The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials Regarding Patient-Reported Outcomes (CONSORT-PRO) statement provides detailed information on how to accurately and transparently report HRQoL in RCTs, and is endorsed by prominent journals. The current systematic review suggests that the CONSORT-PRO statement may not have had a significant impact on the reporting of HRQoL findings in esophagogastric cancer yet [10, 57].

Our study has some limitations. First, the Minimum Standard Checklist for Evaluating HRQoL Outcomes in Cancer Clinical Trials was published in 2003 and might not be as extensive as those published later, such as the CONSORT PRO or the ISOQOL-recommended PRO reporting standards (both published in 2013) [10, 58]. The advantage of the checklist used is the predefined scoring system. In addition, the checklist includes the majority of the essential items of the latter published statements and recommendations based on expert consensus by CONSORT PRO and ISOQOL, respectively. The checklist is based on a minimum set of criteria, whereas the CONSORT-PRO or the ISOQOL-recommended PRO reporting standards elaborate more extensively on different aspects of HRQoL assessments. Extensive tools may be more sensitive to change, which means that the results in the current study might be an underestimation of the true change that occurred over time [7].

Second, the search strategy was limited to reports in English. Consequently, we might have failed to include RCT reports published in other languages—thus limiting our international scope. However, since the major phase II/III trials are published in English, we believe the risk of language bias to be low.

Third, RCTs scored particularly poorly on the item ‘rationale for the instrument used.’ The validated EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaire is most frequently used in esophagogastric cancer, and this can be regarded as the ‘standard’ HRQoL instrument in esophagogastric cancer RCTs. Therefore, devaluing a RCT for not stating a rationale for the instrument used may be an excessively strict approach, as the EORTC questionnaire is consistently applied in order to permit fair comparisons between trials. However, post hoc analysis showed that the results were not different when the criterion ‘rationale for instrument reported’ was omitted. It should be emphasized that when authors use a newly developed or less frequently applied questionnaire, they should state the rationale.

Finally, one might dispute the interpretation of the outcome (ACS) as an interval scale. We adhered to the general practice of analyzing percentages or values between 0 and 1 to two decimal places using parametric statistical techniques.

To improve the quality of HRQoL reporting in future RCTs, we recommend that researchers and clinicians should involve a HRQoL expert in the trial design, execution, analysis, and reporting phases. When the word count is restricted by journals, an extensive appendix or supplementary dataset can be of value. In addition, we would like to affirm the comment by Brundage et al. [6] that researchers and clinicians in advisory positions can stimulate the acceptance of patient-reported outcome reporting standards—such as the CONSORT PRO—by involving editors, reviewers, and related stakeholders.

Conclusion

Although the number of RCTs on palliative systemic therapy for advanced esophagogastric cancer that include an HRQoL endpoint has increased, the quality of HRQoL reporting is highly variable, limited, and did not improve over time. This systematic review highlights the gaps in the current quality of HRQoL reporting in esophagogastric cancer RCTs. The formulation of a priori hypotheses, a clear description of how the instrument is administered, the number of missing data and how those data are handled, and the interpretation of findings are areas for improvement. We recommend that HRQoL should be extensively described in supplementary appendices if good HRQoL reporting is restricted by the word limit of the manuscript. As results from RCTs are crucial to daily practice, reliable and adequate reporting of HRQoL outcomes from RCTs is needed to facilitate clinical decision-making.

References

Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global Cancer Statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:87–108. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21262.

Haj Mohammad N, ter Veer E, Ngai L, Mali R, van Oijen MGH, van Laarhoven HWM. Optimal first-line chemotherapeutic treatment in patients with locally advanced or metastatic esophagogastric carcinoma: triplet versus doublet chemotherapy: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2015;34:429–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10555-015-9576-y.

Wagner AD, Unverzagt S, Grothe W, Kleber G, Grothey A, Haerting J, et al. Chemotherapy for advanced gastric cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;CD004064. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004064.pub3 .

Sanders C, Egger M, Donovan J, Tallon D, Frankel S. Reporting on quality of life in randomised controlled trials: bibliographic study. BMJ. 1998;317:1191–4.

Chassany O, Sagnier P, Marquis P, Fullerton S, Aaronson N. Patient-reported outcomes: the example of health-related quality of life—a European guidance document for the improved integration of health-related quality of life assessment in the drug regulatory process. Drug Inf J. 2002;36:209–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/009286150203600127.

Brundage M, Bass B, Davidson J, Queenan J, Bezjak A, Ringash J, et al. Patterns of reporting health-related quality of life outcomes in randomized clinical trials: implications for clinicians and quality of life researchers. Qual Life Res. 2011;20:653–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-010-9793-3.

Efficace F, Osoba D, Gotay C, Sprangers M, Coens C, Bottomley A. Has the quality of health-related quality of life reporting in cancer clinical trials improved over time? Towards bridging the gap with clinical decision making. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:775–81. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdl494.

Jacobs M, Macefield RC, Blazeby JM, Korfage IJ, Van Berge Henegouwen MI, De Haes HCJM, et al. Systematic review reveals limitations of studies evaluating health-related quality of life after potentially curative treatment for esophageal cancer. Qual Life Res. 2013;22:1787–803. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-012-0290-8.

Efficace F, Bottomley A, Osoba D, Gotay C, Flechtner H, D’haese S, Zurlo A. Beyond the development of health-related quality of life (HRQOL) measures. A checklist for evaluating HRQOL outcomes in cancer clinical trials: does HRQOL evaluation in prostate cancer research inform clinical decision-making? J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3502–11.

Calvert M, Blazeby J, Altman DG, Revicki DA, Moher D, Brundage MD, et al. Reporting of patient-reported outcomes in randomized trials. The CONSORT PRO extension. JAMA. 2013;309:814. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.879.

Ajani JA, Rodriguez W, Bodoky G, Moiseyenko V, Lichinitser M, Gorbunova V, et al. Multicenter phase III comparison of cisplatin/S-1 with cisplatin/infusional fluorouracil in advanced gastric or gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma study: the FLAGS trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1547–53. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2009.25.4706.

Bodoky G, Scheulen ME, Rivera F, Jassem J, Carrato A, Moiseyenko V, et al. Clinical benefit and health-related quality of life assessment in patients treated with cisplatin/S-1 versus cisplatin/5-FU: secondary end point results from the first-line advanced gastric cancer study (FLAGS). J Gastrointest Cancer. 2015;46:109–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12029-014-9680-1.

Al-Batran SE, Pauligk C, Homann N, Hartmann JT, Moehler M, Probst S, et al. The feasibility of triple-drug chemotherapy combination in older adult patients with oesophagogastric cancer: a randomised trial of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Internistische Onkologie (FLOT65 +). Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:835–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2012.09.025.

Kripp M, Al-Batran SE, Rosowski J, Pauligk C, Homann N, Hartmann JT, et al. Quality of life of older adult patients receiving docetaxel-based chemotherapy triplets for esophagogastric adenocarcinoma: a randomized study of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Internistische Onkologie (AIO). Gastric Cancer. 2014;17:181–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-013-0242-1.

Bouché O, Raoul JL, Bonnetain F, Giovannini M, Etienne PL, Lledo G, et al. Randomized multicenter phase II trial of a biweekly regimen of fluorouracil and leucovorin (LV5FU2), LV5FU2 plus cisplatin, or LV5FU2 plus irinotecan in patients with previously untreated metastatic gastric cancer: A Fédération Francophone de Cancérologie. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4319–28. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2004.01.140.

Bramhall SR, Hallissey MT, Whiting J, Scholefield J, Tierney G, Stuart RC, et al. Marimastat as maintenance therapy for patients with advanced gastric cancer: a randomised trial. Br J Cancer. 2002;86:1864–70. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6600310.

Curran D, Pozzo C, Zaluski J, Dank M, Barone C, Valvere V, et al. Quality of life of palliative chemotherapy naive patients with advanced adenocarcinoma of the stomach or esophagogastric junction treated with irinotecan combined with 5-fluorouracil and folinic acid: results of a randomised phase III trial. Qual Life Res. 2009;18:853–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-009-9493-z.

Dank M, Zaluski J, Barone C, Valvere V, Yalcin S, Peschel C, et al. Randomized phase III study comparing irinotecan combined with 5-fluorouracil and folinic acid to cisplatin combined with 5-fluorouracil in chemotherapy naive patients with advanced adenocarcinoma of the stomach or esophagogastric junction. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:1450–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdn166.

Duffour J, Bouché O, Rougier P, Milan C, Bedenne L, Seitz JF, et al. Safety of cisplatin combined with continuous 5-FU versus bolus 5-FU and leucovorin, in metastatic gastrointestinal cancer (FFCD 9404 randomised trial). Anticancer Res. 2006;26:3877–83.

Glimelius B, Ekström K, Hoffman K, Graf W, Sjödén PO, Haglund U, et al. Randomized comparison between chemotherapy plus best supportive care with best supportive care in advanced gastric cancer. Ann Oncol. 1997;8:163–8. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008243606668.

Gubanski M, Johnsson A, Fernebro E, Kadar L, Karlberg I, Flygare P, et al. Randomized phase II study of sequential docetaxel and irinotecan with 5-fluorouracil/folinic acid (leucovorin) in patients with advanced gastric cancer: the GATAC trial. Gastric Cancer. 2010;13:155–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-010-0553-4.

Gubanski M, Glimelius B, Lind PA. Quality of life in patients with advanced gastric cancer sequentially treated with docetaxel and irinotecan with 5-fluorouracil and folinic acid (leucovin). Med Oncol. 2014;31:906. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12032-014-0906-7.

Guimbaud R, Louvet C, Ries P, Ychou M, Maillard E, André T, et al. Prospective, randomized, multicenter, phase III study of fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan versus epirubicin, cisplatin, and capecitabine in advanced gastric adenocarcinoma: a French intergroup (Fédération Francophone de Cancérologie Digestive. Féd J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3520–6. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2013.54.1011.

Nuemi G, Devilliers H, Le Malicot K, Guimbaud R, Lepage C, Quantin C. Construction of quality of life change patterns: example in oncology in a phase III therapeutic trial (FFCD 0307). Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2015;13:151. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-015-0342-1.

Hall PS, Lord SR, Collinson M, Marshall H, Jones M, Lowe C, et al. A randomised phase II trial and feasibility study of palliative chemotherapy in frail or elderly patients with advanced gastroesophageal cancer (321GO). Br J Cancer. 2017;116:472–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2016.442.

Hecht JR, Bang YJ, Qin SK, Chung HC, Xu JM, Park JO, et al. Lapatinib in combination with capecitabine plus oxaliplatin in human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive advanced or metastatic gastric, esophageal, or gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma: TRIO-013/LOGiC—a randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:443–51. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2015.62.6598.

Hwang IG, Ji JH, Kang JH, Lee HR, Lee HY, Chi KC, et al. A multi-center, open-label, randomized phase III trial of first-line chemotherapy with capecitabine monotherapy versus capecitabine plus oxaliplatin in elderly patients with advanced gastric cancer. J Geriatr Oncol. 2017;8:170–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2017.01.002.

Kim GM, Jeung HC, Rha SY, Kim HS, Jung I, Nam BH, et al. A randomized phase II trial of S-1-oxaliplatin versus capecitabine-oxaliplatin in advanced gastric cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:518–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2011.12.017.

Ohtsu A, Shah MA, Van Cutsem E, Rha SY, Sawaki A, Park SR, et al. Bevacizumab in combination with chemotherapy as first-line therapy in advanced gastric cancer: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3968–76. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2011.36.2236.

Park SH, Lee WK, Chung M, Lee Y, Han SH, Bang S-M, et al. Paclitaxel versus docetaxel for advanced gastric cancer: a randomized phase II trial in combination with infusional 5-fluorouracil. Anticancer Drugs. 2006;17:225–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001813-200602000-00015.

Park SH, Nam E, Park J, Cho EK, Shin DB, Lee JH, et al. Randomized phase II study of irinotecan, leucovorin and 5-fluorouracil (ILF) versus cisplatin plus ILF (PILF) combination chemotherapy for advanced gastric cancer. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:729–33. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdm502.

Rao S, Starling N, Cunningham D, Sumpter K, Gilligan D, Ruhstaller T, et al. Matuzumab plus epirubicin, cisplatin and capecitabine (ECX) compared with epirubicin, cisplatin and capecitabine alone as first-line treatment in patients with advanced oesophago-gastric cancer: a randomised, multicentre open-label phase II study. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:2213–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdq247.

Ross P, Nicolson M, Cunningham D, Valle J, Seymour M, Harper P, et al. Prospective randomized trial comparing mitomycin, cisplatin, and protracted venous-infusion fluorouracil (PVI 5-FU) with epirubicin, cisplatin, and PVI 5-FU in advanced esophagogastric cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1996–2004. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2002.08.105.

Roth AD, Fazio N, Stupp R, Falk S, Bernhard J, Saletti P, et al. Docetaxel, cisplatin, and fluorouracil; docetaxel and cisplatin; and epirubicin, cisplatin, and fluorouracil as systemic treatment for advanced gastric carcinoma: a randomized phase II trial of the Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3217–23. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2006.08.0135.

Ryu MH, Baba E, Lee KH, Park YI, Boku N, Hyodo I, et al. Comparison of two different S-1 plus cisplatin dosing schedules as first-line chemotherapy for metastatic and/or recurrent gastric cancer: a multicenter, randomized phase III trial (SOS). Ann Oncol. 2015;26:2097–101. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdv316.

Sadighi S, Mohagheghi MA, Montazeri A, Sadighi Z. Quality of life in patients with advanced gastric cancer: a randomized trial comparing docetaxel, cisplatin, 5-FU (TCF) with epirubicin, cisplatin, 5-FU (ECF). BMC Cancer. 2006;6:274. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-6-274.

Tebbutt NC, Norman A, Cunningham D, Iveson T, Seymour M, Hickish T, et al. A muticentre, randomised phase III trial comparing protracted venous infusion (PVI) 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) with PVI 5-FU plus mitomycin C in patients with inoperable oesophago-gastric cancer. Ann Oncol. 2002;13:1568–75. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdf273.

Tebbutt NC, Cummins MM, Sourjina T, Strickland A, Van Hazel G, Ganju V, et al. Randomised, non-comparative phase II study of weekly docetaxel with cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil or with capecitabine in oesophagogastric cancer: the AGITG ATTAX trial. Br J Cancer. 2010;102:475–81. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6605522.

Tebbutt NC, Price TJ, Ferraro DA, Wong N, Veillard AS, Hall M, et al. Panitumumab added to docetaxel, cisplatin and fluoropyrimidine in oesophagogastric cancer: ATTAX3 phase II trial. Br J Cancer. 2016;114:505–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2015.440.

Ajani JA, Moiseyenko VM, Tjulandin S, Majlis A, Constenla M, Boni C, et al. Quality of life with docetaxel plus cisplatin and fluorouracil compared with cisplatin and fluorouracil from a phase III trial for advanced gastric or gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma: the V-325 study group. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3210–6. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2006.08.3956.

Van Cutsem E, Moiseyenko VM, Tjulandin S, Majlis A, Constenla M, Boni C, et al. Phase III study of docetaxel and cisplatin plus fluorouracil compared with cisplatin and fluorouracil as first-line therapy for advanced gastric cancer: a report of the V325 Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4991–7. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2006.06.8429.

Wadler S, Brain C, Catalano P, Einzig AI, Cella D, Benson III AB. Randomized phase II trial of either fluorouracil, parenteral hydroxyurea, interferon-α-2a, and filgrastim or doxorubicin/docetaxel in patients with advanced gastric cancer with quality-of-life assessment: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group study E6296. Cancer J. 2002;8:282–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/00130404-200205000-00013.

Waters JS, Norman A, Cunningham D, Scarffe JH, Webb A, Harper P, et al. Long-term survival after epirubicin, cisplatin and fluorouracil for gastric cancer: results of a randomized trial. Br J Cancer. 1999;80:269–72. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6690350.

Webb A, Cunningham D, Scarffe JH, Harper P, Norman A, Joffe JK, et al. Randomized trial comparing epirubicin, cisplatin, and fluorouracil versus fluorouracil, doxorubicin, and methotrexate in advanced esophagogastric cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:261–70.

Yoshino S, Nishikawa K, Morita S, Takahashi T, Sakata K, Nagao J, et al. Randomised phase III study of S-1 alone versus S-1 plus lentinan for unresectable or recurrent gastric cancer (JFMC36-0701). Eur J Cancer. 2016;65:164–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2016.06.012.

Dutton SJ, Ferry DR, Blazeby JM, Abbas H, Dahle-Smith A, Mansoor W, et al. Gefitinib for oesophageal cancer progressing after chemotherapy (COG): a phase 3, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:894–904. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70024-5.

Ford HER, Marshall A, Bridgewater JA, Janowitz T, Coxon FY, Wadsley J, et al. Docetaxel versus active symptom control for refractory oesophagogastric adenocarcinoma (COUGAR-02): an open-label, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:78–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70549-7.

Fuchs CS, Tomasek J, Yong CJ, Dumitru F, Passalacqua R, Goswami C, et al. Ramucirumab monotherapy for previously treated advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (REGARD): an international, randomised, multicentre, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2014;383:31–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61719-5.

Lee KW, Kim BJ, Kim MJ, Han HS, Kim JW, Park YI, Park SR. A multicenter randomized phase II study of docetaxel vs. docetaxel plus cisplatin vs. docetaxel plus S-1 as second-line chemotherapy in metastatic gastric cancer patients who had progressed after cisplatin plus either S-1 or capecitabine. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51:S432.

Li J, Qin S, Xu J, Xiong J, Wu C, Bai Y, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial of apatinib in patients with chemotherapy-refractory advanced or metastatic adenocarcinoma of the stomach or gastroesophageal junction. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1448–54. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2015.63.5995.

Li J, Qin S, Xu J, Guo W, Xiong J, Bai Y, et al. Apatinib for chemotherapy-refractory advanced metastatic gastric cancer: results from a randomized, placebo-controlled, parallel-arm, phase II trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3219–25. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2013.48.8585.

Ohtsu A, Ajani JA, Bai Y-X, Bang Y-J, Chung H-C, Pan H-M, et al. Everolimus for previously treated advanced gastric cancer: results of the randomized, double-blind, phase III GRANITE-1 study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3935–43. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2012.48.3552.

Al-Batran SE, Van Cutsem E, Oh SC, Bodoky G, Shimada Y, Hironaka S, et al. Quality-of-life and performance status results from the phase III RAINBOW study of ramucirumab plus paclitaxel versus placebo plus paclitaxel in patients with previously treated gastric or gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:673–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdv625.

Wilke H, Muro K, Van Cutsem E, Oh SC, Bodoky G, Shimada Y, et al. Ramucirumab plus paclitaxel versus placebo plus paclitaxel in patients with previously treated advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (RAINBOW): a double-blind, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:1224–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70420-6.

Bang YJ, Van Cutsem E, Feyereislova A, Chung HC, Shen L, Sawaki A, et al. Trastuzumab in combination with chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for treatment of HER2-positive advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer (ToGA): a phase 3, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;376:687–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61121-X.

Satoh T, Bang Y-J, Gotovkin EA, Hamamoto Y, Kang Y-K, Moiseyenko VM, et al. Quality of life in the Trastuzumab for Gastric Cancer trial. Oncologist. 2014;19:712–19. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0058.

Efficace F, Fayers P, Pusic A, Cemal Y, Yanagawa J, Jacobs M, et al. Quality of patient-reported outcome reporting across cancer randomized controlled trials according to the CONSORT patient-reported outcome extension: a pooled analysis of 557 trials. Cancer. 2015;121:3335–42. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.29489.

Brundage M, Blazeby J, Revicki D, Bass B, De Vet H, Duffy H, et al. Patient-reported outcomes in randomized clinical trials: development of ISOQOL reporting standards. Qual Life Res. 2013;22:1161–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-012-0252-1.

Acknowledgements

All authors had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors gave final approval for the submission of the manuscript.

Author contributions

Study concepts: EtV, JJvK, MS, MvO, HvL. Study design: EtV, JJvK, MS, MvO, HvL. Data acquisition; EtV, JJvK. Quality control of data and algorithms: EtV, JJvK. Data analysis and interpretation: JJvK, EtV, MS, NHM, MvO, HvL. Statistical analysis: JJvK, EtV. Manuscript preparation: JJvK, EtV. Manuscript editing: JJvK, EtV, MS, NHM, MvO, HvL. Manuscript review: JJvK, EtV, MS, NHM, MvO, HvL.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the Dutch Cancer Society (KWF), grant number UVA 2014-7000.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethics statement

In all studies that were included in this systematic review, it was declared that all procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and later versions. Also, in all studies it was declared that informed consent or a substitute for it was obtained from all patients before they were included in the studies.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

ter Veer, E., van Kleef, J.J., Sprangers, M.A.G. et al. Reporting of health-related quality of life in randomized controlled trials involving palliative systemic therapy for esophagogastric cancer: a systematic review. Gastric Cancer 21, 183–195 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-018-0792-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-018-0792-3