Abstract

Background

Currently, only trastuzumab, ramucirumab, and apatinib effectively treat gastric cancer. Thus, additional novel targets are required for this disease.

Methods

We investigated the immunohistochemical and fluorescence in situ hybridization expression of MET, ROS1, and ALK in four gastric cell lines and a cohort of 98 gastric cancer patients. Crizotinib response was studied in vitro and in vivo.

Results

Crizotinib potently inhibited in vitro cell growth in only one cell line, which also showed MET amplification. A positive correlation between crizotinib sensitivity and MET overexpression was observed (P = 0.045) in the histoculture drug response assay. Meanwhile, patient-derived tumor xenograft mouse models transplanted with tissues with higher MET protein expression displayed a highly selective sensitivity to crizotinib. In the 98 patients, MET overexpression was found in 42 (42.9 %) and MET was amplified in 4 (4.1 %). ROS1 and ALK overexpression were found in 25 (25.5 %) and 0 patients, respectively. However, none of the patients screened harbored ALK or ROS1 rearrangements. No significant association was found between overall survival and MET or ROS1 status. We also observed a stage IV gastric cancer patient with MET amplification who experienced tumor shrinkage and clinical benefit after 3 weeks of crizotinib as fourth-line treatment.

Conclusions

Crizotinib may induce clinically relevant anticancer effects in MET-overexpressed or MET-amplified gastric cancer patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There is increasing interest in the development of targeted therapies for gastric cancer after the encouraging results of trastuzumab in human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2)-positive populations. However, the reported incidence of HER2-positive gastric cancer patients varies from 7 to 34 % [1–6], leaving a considerable proportion of cases whose clinical regimens are limited to chemotherapy. Additional aberrantly activated receptors and downstream pathways are now being explored, including epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR-2), fibroblastic growth factor receptor (FGFR), and the MET proto-oncogene (MET), to assess their therapeutic potential in gastric cancer.

Crizotinib (PF-02341066), an oral small molecule inhibitor that targets both anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) and MET, has shown tremendous promise in the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) harboring either ALK [7, 8] or c-ros avian UR2 sarcoma virus oncogene homolog 1 (ROS1) [9] rearrangements or MET amplifications [10]. In addition to NSCLC, the oncogenic fusion gene of ALK has been identified in several types of cancer, such as anaplastic large-cell lymphoma [11] and neuroblastoma [12]. In lung cancer, ALK rearrangement is associated with the presence of signet ring cells [13]. However, a greater understanding of ALK in gastric cancer is required. Earlier studies failed to find ALK fusion in 555 gastrointestinal cancer samples [14] and in 432 gastric cancer samples [15].

Rearrangement in ROS1 has previously been found in 1–2 % of NSCLCs [16] and 8.7 % of cholangiocarcinomas [17]. However, ROS1 rearrangement is generally not expressed in the stomach; its incidence was only 0.6 % according to ROS1 break-apart fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) [18]. Due to the limited number of cases reported, no clinicopathological characteristics have been ascribed to this potentially unique molecular subset of gastric cancer. Pronounced clinical responses to crizotinib have been seen in NSCLC [10], gastric cancer [19], and glioblastoma [20] patients with MET amplification, which is consistent with its mechanism of action. MET gene mutations in the kinase domain are almost lacking in gastric carcinomas. Therefore, the MET gene abnormality is mostly attributed to gene amplification [21–23]. MET-amplified gastric cancer cells have shown marked sensitivity to crizotinib both in vitro and in vivo [24]. MET-positive tumors have been significantly associated with increased metastatic potential, increased depth of tumor invasion [25, 26], poor differentiation, advanced stage, and poor prognosis [18]. MET overexpression, examined by immunohistochemistry (IHC), has been reported in approximately 50–60 % of advanced gastric cancers [21, 25, 26].

Given that crizotinib might be a promising therapeutic agent in a specific group of gastric cancer patients, our present study was performed to examine the expression of MET, ROS1, and ALK in four gastric cancer cell lines and a single cohort of gastric cancer patients. Sensitivity and response to crizotinib were also determined using a histoculture cytotoxicity assay and patient-derived tumor xenograft mouse models.

Materials and methods

In vitro cytotoxicity studies

The cytotoxicity of crizotinib in the gastric cell lines MKN45, AGS, SNU-1, and N87 was determined by 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium (MTT) assay. Cells were seeded in 96-well plates (3000 cells per well) with antibiotic-free RPMI 1640 plus 10 % fetal bovine serum at 37 °C with 5 % CO2 for 24 h. The cells were then treated with crizotinib for another 72 h to determine the 50 % inhibition concentrations (IC50). Optical density was spectrophotometrically measured at 570 nM. Each experiment was carried out in triplicate and data are presented as geometric means.

Western blotting

Western blotting analysis was performed in four gastric cell lines as described previously [27]. Cells were incubated in the absence or presence of 0.05 nM crizotinib for 48 h, after which cell lysates were prepared and subjected to western blotting analysis. Primary antibodies against phosphorylated MET (Tyr1234/1235), total protein kinase B (AKT), phosphorylated AKT, total extracellular signal regulated kinase (ERK), phosphorylated ERK, total and phosphorylated forms of signal transducers and activators of transcription 3 (STAT3) were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). Antibodies against total MET were from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA), and those against β-actin were from Sigma–Aldrich (Ronkonkoma, NY, USA). All antibodies were used at 1:1000 dilution with the exception of those to β-actin (1:200).

Patients

This study included 98 patients who underwent gastrectomy at the General Surgery Department of Drum Tower Hospital between 2010 and 2012. MET, ROS1, and ALK were examined in all samples. Of these, 40 samples that had sufficient freshly removed tumor tissues were further used for measurement of in vitro crizotinib sensitivity by histoculture drug response assay, and 30 samples had sufficient tumor tissues for further patient-derived tumor xenograft mouse model analysis. The present study was approved by the ethics committee of Drum Tower Hospital and informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Histoculture drug response assay (HDRA)

Sensitivity to crizotinib in vitro was examined in 40 tumor samples by histoculture drug response assay. Briefly, approximately 10-mg fresh tumor specimens were placed on prepared collagen surfaces in 24-well microplates. There were eight parallel culture wells for crizotinib testing and eight parallel culture wells for control. Plates were incubated for 7 days at 37 °C in the presence of crizotinib dissolved in RPMI 1640 medium containing 20 % fetal bovine serum to a concentration of 0.0625 µg/ml from a 50-µg/ml stock solution. An MTT assay was then used to examine the cytotoxicity. Absorbance per gram of cultured tumor tissue was determined using the mean absorbance of tissue from eight parallel culture wells. The weight of tumor tissue was determined before culture. The inhibition rate was calculated using the following formula: inhibition rate (%) = (1 − T/C) × 100, where T is the mean absorbance of treated tumor/weight and C is the mean absorbance of control tumor/weight.

In vivo antitumor efficacy in xenograft models

Thirty samples that had sufficient freshly removed tumor tissues were further used for measurement of in vivo crizotinib sensitivity by patient-derived tumor-xenograft mouse model antitumor studies. Balb/c nude mice (4–6 weeks old; Vital River, Beijing, China) weighing 18–22 g were raised under a specific pathogen-free environment. Each tumor sample was implanted into 10 mice. A fresh tumor specimen (approximately 27 mm3) was subcutaneously transplanted within 30 min into the lower right axilla of each moce. When 80 % of the tumors had reached a volume of 100 mm3, the mice were randomly divided into vehicle and treatment groups (five per group). Five tumors (17.8 %) grew in the immunodeficient mouse models. Tumor-bearing nude mice were treated with crizotinib 10 mg/kg/qd (treatment group) or 0.9 % saline (vehicle control group) by gavage. Subcutaneous tumor volumes and mice body weight were measured twice a week. Tumor volumes were calculated by the formula: tumor volume = [length × (width)2]/2. Relative tumor volumes were calculated by V/V1, where V is the absolute tumor volume and V1 is the average tumor volume of the group before the first crizotinib dosing.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

IHC analyses were performed on 2-mm-thick, formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections. Slides were deparaffinized and pretreated with 3 % hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) in methanol. Antigen retrieval was then performed with 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0 in a steam pressure cooker. MET (rabbit monoclonal, clone EP1454Y; Abcam), ROS1 (rabbit polyclonal; Abcam), and ALK (mouse monoclonal, clone 5A4; Abcam) antibodies were diluted to 1:100, 1:50, and 1:50, respectively, and the sections were incubated with the primary antibody at 4 °C overnight, followed by secondary antibody. All slides were counterstained with hematoxylin. The stained slides were separately reviewed by two pathologists who were blinded to the FISH results and the patients’ clinicopathologic characteristics. Slides were scored using HistoScore (H score), which depends on two parameters as described previously. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus review. The first parameter was the intensity of the stained cells (0–3, no evidence of staining to strong staining reaction) and the second parameter was an estimate of the percentage of the cells that were stained (≤5 % = 0, 6–25 % = 1, 26–50 % = 2, 51–75 % = 3, and >75 % = 4). H was the intensity score multiplied by the percentage of positive scores. The final IHC result was categorized as IHC 0 if H = 0, IHC1+ if H = 1–4, IHC 2+ if H = 5–8, and IHC 3+ if H was more than 8 [28]. A minimum of 100 cells were evaluated in calculating the H score. Patients with IHC 2–3+ were considered to be overexpressing the protein.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis

FISH analysis was performed on 4-mm-thick, formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections. MET/CEP7 FISH probe (Vysis MET SpectrumRed FISH probe kit and CEP7 Spectrum Green probe; Abbott Molecular, Abbot Park, IL, USA) was used to identify MET amplifications. For ALK and ROS1 testing, commercially available break-apart probes specific to the ALK and ROS1 genes (Vysis LSI Dual Color and Break Apart Rearrangement Probe, respectively; Abbott Molecular) were used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. FISH analysis was performed using an Olympus BX61 epifluorescence microscope (Olympus, NY, USA). At least 60 tumor nuclei were counted for each case. Images were captured using a charge-coupled device (CCD) camera and merged using dedicated software (CytoVision, Santa Clara, CA, USA). For MET analysis, tumors with a MET/CEP7 ratio of ≥2, the presence of tight gene clusters, or ≥15 copies of the gene in ≥10 % tumor cells were considered to show amplification, as previously reported [24, 29]. When samples displayed more than 15 % break-apart signals or isolated red signals in 50 tumor cells, ROS1 or ALK rearrangements were scored as positive [30, 31].

Statistical analysis

Spearman’s rank method was used to assess the correlation between the IHC results and in vitro crizotinib sensitivity. A two-sample t test was used to compare the tumor volumes of different groups. Characteristics of the two groups were compared using the chi-square test. The Mann–Whitney U test and the Kruskal–Wallis test were used to gauge the associations between crizotinib sensitivity and patients’ clinicopathological parameters. The survival distributions were obtained by the Kaplan–Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. All statistical calculations were performed with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences for Windows version 17 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). A two-sided P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

MET amplification is associated with increased sensitivity to crizotinib in gastric cancer cell lines

The cytotoxicity of crizotinib in four gastric cancer cell lines, as determined by MTT assay, as well as the MET, ROS1, and ALK statuses of the cell lines according to IHC and FISH are summarized in Table 1. A strong antiproliferative response to crizotinib was only achieved in the MKN45 cell line (IC50 value of 40 nM), which showed MET IHC 3+ and also MET amplification by FISH (Fig. 1a). All other cell lines showed minimal responses to crizotinib (IC50 values >1.4 µM). To assess the pharmacodynamic modulation of MET signaling using crizotinib in vitro, western blotting analysis was conducted. MET phosphorylation was only observed in MKN45; it was not seen in non-MET-amplified cell lines (Fig. 1b). Crizotinib inhibited the phosphorylation of MET and its downstream signal transducers AKT, ERK, and STAT3 in gastric cancer cell line MKN45, indicating that the antiproliferative effect of crizotinib is exerted through the inhibition of phospho-cMET and downstream signaling (Fig. 1c).

Effects of crizotinib on human gastric cancer cell lines classified according to MET amplification status. a Effects of crizotinib on cell growth as determined with the MTT assay. b MKN45, AGS, SNU-1, and N87 were subjected to western blotting analysis with antibodies to phosphorylated or total forms of MET. c MKN45 cell lines were subjected to western blotting analysis with antibodies to phosphorylated or total forms of AKT, ERK, or STAT3

Patient characteristics

All 98 patients had histologically proven gastric adenocarcinoma. The median age was 59.0 years (range 30–82). Most patients were male (72.4 %). Of the 98 patients, 2 (2.0 %) had stage I, 7 (7.1 %) had stage II, and 89 (90.8 %) had stage III disease at the time of diagnosis (Table 2).

MET protein overexpression is associated with increased sensitivity to crizotinib in histoculture drug response assay

Crizotinib sensitivity was successfully tested in 40 tumor samples. There were no significant associations between crizotinib sensitivity and clinical characteristics, including age (P = 0.09), sex (P = 0.73), histology (P = 0.17), tumor site (P = 0.55), stage (P = 0.28), or histological grade (P = 0.47). Of the 40 specimens, 21 (52.5 %) showed MET overexpression. Only one (2.5 %) specimen was MET positive in FISH analysis. Fourteen (35.0 %) tumors had ROS1 overexpression and none had ROS1 amplification. All samples were negative for ALK by IHC or FISH analysis. The inhibition rate in the histoculture drug response assay varied from 13 to 86 % (median 52 %). The inhibition rate of the only MET-amplified gastric cancer specimen was 69 %, meaning that it was considered sensitive to crizotinib. A significant difference could be observed between the inhibition rates of crizotinib in the MET IHC positive group and the MET IHC negative group (P = 0.027). A positive correlation was observed between crizotinib sensitivity and MET overexpression (P = 0.045, Fig. 2). No correlation was observed between crizotinib sensitivity and MET amplification (P = 0.966), probably due to the limited number of amplified cases. No correlation was observed between crizotinib sensitivity and ROS1 IHC results (P = 0.71).

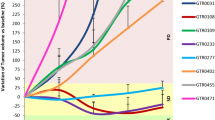

MET protein overexpression predicts selective sensitivity to crizotinib in vivo

Of the five freshly removed tumor tissues that were used to create patient-derived tumor xenograft mouse models, one tumor tissue was MET 2+/ROS1 2+/ALK 0+, three were MET 1+/ROS1 1+/ALK 0+, and the remaining sample was negative for MET, ROS1, and ALK by IHC. No samples showed amplification of MET or rearrangement of ROS1 and ALK by FISH analysis. Nude mice implanted with MET 2+/ROS1 2+/ALK 0+ showed statistically significant tumor regression when compared with vehicle controls (P < 0.001, Fig. 3a). In contrast, subcutaneous nude mice implanted with MET 1+/ROS1 1+/ALK 0+ (Fig. 3b) or triple-negative (Fig. 3c) tissue did not show significant tumor regression over the same period of crizotinib treatments.

Tumor volumes after crizotinib treatment in patient-derived tumor xenograft mouse models. a Nude mice bearing MET 2+/ROS1 2+/ALK 0+ human gastric cancer tissue (**P < 0.001), b nude mice bearing MET 1+/ROS1 1+/ALK 0+ human gastric cancer tissue, and c nude mice bearing MET 0+/ROS1 0+/ALK 0+ human gastric cancer tissue

MET, ROS1, and ALK gene alterations and overall survival

The prevalence of MET, ROS1, and ALK protein overexpression and gene amplification and their associations with clinicopathological characteristics and survival were evaluated in 98 patients. MET overexpression (as defined by IHC 2+ or 3+) was found in 42 patients (42.9 %) (Fig. 4a). FISH analysis showed a MET amplification rate of 4.1 % (4/98) (Fig. 4b, c). MET amplification was found in 4 out of 42 patients (9.5 %) with MET overexpression, but in none of the 56 patients with MET IHC scores of 0 or 1+. ROS1 staining was visible in the perinuclear area with a dot-like accentuation in gastric cancer. Twenty-five samples (25.5 %) exhibited ROS1 protein overexpression (Fig. 4d). Positive ROS1 IHC staining correlated with male sex (P = 0.01), signet ring cell carcinoma histology (P = 0.002), and advanced stage (P = 0.02). Although ROS1 IHC positivity was relatively common, no cases were positive for ROS1 in FISH analysis (Fig. 4e). In addition, ALK gene amplification and protein overexpression were not seen in any of these samples (Fig. 4f, g).

Representative gastric cancer cases with overexpression and amplification of MET, ROS1, and ALK. a Strong membrane and cytoplasmic staining (IHC 3+) for MET. b A case positive for MET amplification (red signal MET, green signal CEP7). c A case negative for MET amplification (red signal MET, green signal CEP7). d Strong ROS1 staining (IHC 3+) in the perinuclear area with dot-like accentuation. e ROS1 FISH without split signals. f A case negative for ALK IHC. g ALK FISH without split signals

The median overall survival was 14 months (95 % CI = 11.9–16.1 months) in the overall patient group. There were no significant associations between overall survival and age (P = 0.16), sex (P = 0.75), Lauren typing (P = 0.33), MET protein levels (P = 0.21), or ROS1 protein levels (P = 0.14).

Clinical responses to crizotinib in a MET-amplified gastric cancer patient

A 31-year-old female stage IV gastric cancer patient with MET amplification and MET overexpression (IHC 3+) (Fig. 5a, b, c) but without gene rearrangement and/or protein overexpression of ROS1 and ALK was treated with crizotinib 250 mg twice daily following progression after third-line chemotherapy. Tumor markers decreased rapidly after 3 weeks of treatment with crizotinib. Computed tomography scan showed a partial response to treatment with reduction of tumor burden (partial response by Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors; Fig. 5d, e). She also showed rapid pain relief and improved performance status after treatment.

Diagnostic features and response of a MET-amplified gastric cancer patient who responded to crizotinib. a Hematoxylin and eosin staining. b Strong MET staining (IHC 3+). c Positive for MET amplification (red signal MET, green signal CEP7). d Pretreatment image of the patient. e Partial response after 3 weeks of crizotinib (250 mg twice daily)

Discussion

Evidence exists for the role of MET in signaling pathways such as the PI-3-kinase/AKT, Ras/RAF/MEK/ERK, STAT, and FAK pathways, which are associated with cell proliferation, migration, invasion, and angiogenesis [32–34]. A number of novel agents targeting the MET/HGF axis have undergone clinical trials in gastric cancer patients, including MET antibodies such as onartuzumab (MetMab) and rilotumumab and small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as crizotinib, AMG337, INC280 and volitinib.

Preliminary results from trials of MET inhibitors have generated both hope and disappointment. In a previous phase II study of rilotumumab in combination with epirubicin, cisplatin, and capecitabine (ECX) as first-line treatment in patients with advanced gastric or esophagogastric junction cancer, the addition of rilotumumab to ECX appeared to improve the progression-free survival (PFS) outcome. Patients with MET-positive cancer in the rilotumumab treatment arm had a longer median overall survival than patients in the ECX plus placebo treatment group (10.6 vs 5.7 months) [35]. However, a phase III study of rilotumumab (RILOMET-1) was stopped early due to an increased number of deaths in the rilotumumab and chemotherapy treatment arm when compared to the chemotherapy treatment arm [36]. Unfortunately, preliminary results of a phase II study of onartuzumab in combination with mFOLFOX6 in metastatic HER2-negative gastric cancer revealed a higher rate of serious toxicities in the experimental arm but a similar progression-free survival [37]. Due to these disappointing results, the METGastric phase III study was recently stopped. While results obtained using the monoclonal antibody appeared to be promising, late-stage clinical trials have pointed to discouraging outcomes. There is an urgent need for detailed results from these studies to clarify these inconsistent results. Conversely, treatment with MET tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) has yielded some encouraging results. Crizotinib has shown efficacy in esophagogastric adenocarcinoma with MET amplification [19]. In a phase I trial, two of four patients who had MET-amplified gastric or esophageal junction tumors experienced tumor shrinkage upon crizotinib treatment [19]. Meanwhile, in a phase I study of AMG 337, five of seven gastric cancer patients harboring MET amplification achieved an objective response [37]. Building on these promising results, a phase II study of AMG337 in gastric cancer is ongoing. An important challenge facing the effective development of MET-targeted agents is to pinpoint a methodology for identifying the population that could achieve maximal benefit. Success will be dependent on the accurate assessment of the genetic alterations in patients. Earlier clinical trials considering onartuzumab and rilotumumab used MET IHC overexpression as a patient selection approach. Later phase I/II gastric cancer trials of AMG337, INC280, and volitinib used MET amplification by FISH or a sequential approach that combined IHC and FISH. The present study, based on the use of IHC followed by confirmatory FISH analysis, is the first to comprehensively characterize MET, ROS1, and ALK oncogenic alterations in gastric cell lines and a cohort of gastric cancer patients.

We examined MET, ROS1, and ALK status in gastric cancer cell lines and compared the effects of crizotinib between a MET-amplified cell line and various cell lines that were negative for this genetic alteration. We confirmed that MKN45 was positive for MET amplification and displayed high sensitivity to the crizotinib-targeted agent in vitro, and that hypersensitivity to crizotinib was predominantly dependent on MET signaling through the inhibition of phospho-MET and the downstream signaling ERK, AKT, and STAT pathways—results that were largely consistent with those of previous reports [24, 32, 38].

A higher MET protein overexpression rate (42.9 %) was found in our current analysis compared with other studies in Chinese gastric cancer patients [24, 32]. These results are likely a consequence of higher proportion of advanced stage. In our study, 89 patients (90.8 %) had stage III disease. A previous study of advanced gastric cancer showed that approximately 50 % of the population had MET protein overexpression [26]. IHC could be considered a practical screening test for MET amplification. In our present study, MET amplification was found in only four patients, in accordance with the protein overexpression profile, which is a similar rate to that reported in a previous publication [32]. Although MET amplification has been described as an unfavorable factor for outcomes in gastric cancer, ovarian cancer, and NSCLC [39], a similar effect on overall survival was not observed in our current cohort, probably due to the small number of amplified patients. In our histoculture drug response assay tests, a positive correlation between crizotinib sensitivity and MET overexpression was observed. Furthermore, in vivo sensitivity to crizotinib was observed in nude mice transplanted with tumor tissues showing relatively high MET (IHC 2+) expression. We also observed that a patient with advanced gastric cancer with MET amplification experienced tumor shrinkage (partial response according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors) after 3 weeks of treatment with crizotinib following progression after third-line chemotherapy. All of these data support the notion that MET overexpression and amplification might represent a potential therapeutic subcategory in gastric cancer patients. These findings are in line with previously reported results that crizotinib possesses clinical activity towards esophageal and gastroesophageal adenocarcinomas harboring MET amplification [19], as well as recent parallel results in a NSCLC case [10].

Although the MET-amplified sample showed sensitivity to crizotinib in histoculture drug response assay tests, no correlation was observed between crizotinib sensitivity and MET amplification, probably because only one sample showed MET amplification. Furthermore, MET can be examined at both the gene and the protein level. Gene amplification by FISH is considered the gold standard at present. Meanwhile, IHC is the most useful technique for identifying protein expression. Unfortunately, a consensus on the evaluation criteria for MET positivity using IHC or FISH is not currently available. Moreover, whether IHC overexpression or FISH amplification truly represent genetic alterations remains unknown. In our study, we used a strict FISH-positive standard. Only tumors with a MET/CEP7 ratio of ≥2 or the presence of tight gene clusters or ≥15 copies of the gene in ≥10 % tumor cells were considered to show MET amplification. Samples with high polysomy were classified FISH negative. Samples that were FISH negative but showed MET overexpression might also be sensitive to crizotinib. When we compared the inhibition rate of crizotinib in the MET IHC 2–3+ group with that in the MET IHC 0–1+ group, a significant difference was found (P = 0.027). Nonetheless, histoculture drug response assays have some technical limitations, including cancer heterogeneity and treatment-associated adverse events. To overcome these problems, we utilized eight parallel culture wells containing materials drawn from different parts of a patient’s tumor sample for crizotinib sensitivity testing and eight parallel culture wells for the control.

The success application of crizotinib in ALK-rearranged NSCLC [40, 41] has opened the door to the possible treatment of other ALK-rearranged carcinomas with crizotinib. Data from previous reports on lung cancer showed that most of the samples with ROS1 and ALK rearrangements had signet ring cell histology [13, 42]. Consistent with this evidence, the results of the present study also suggest that ROS1 protein overexpression is related to certain clinicopathologic features, such as male sex, advanced tumor stage, and signet ring cell carcinoma histology. Signet ring cell carcinoma is more common in gastrointestinal tumors that have different biological characteristics. Advanced signet ring cell carcinoma has long been thought to have a worse prognosis than other forms of gastric cancer due to a high risk of peritoneal metastasis [43]. Thus, exploring ROS1 and ALK rearrangements may lead to a breakthrough in the treatment of patients with signet ring cell carcinoma. However, none of our patients harbored ROS1/ALK rearrangement, suggesting that its prevalence in gastric cancer is low. Similar to our current results, a previous study of 1889 colorectal carcinoma patients reported that no cases were positive for ROS1 by IHC, and that only one case (0.05 %) showed ALK rearrangement [44]. Similarly, a study that was specifically performed to analyze the incidence of ALK translation in signet ring cell carcinoma failed to detect any ALK translocation in signet ring cell carcinomas of the upper gastrointestinal tract [45]. Another study failed to detect the presence of ALK fusion in 555 gastrointestinal cancer samples [14] and 432 gastric cancer samples [15]. We therefore conclude that ALK fusion is not present in gastrointestinal cancer and might be specific to NSCLC, particularly adenocarcinoma.

Novel ALK fusion genes, C2orf44-ALK [46] and CAD-ALK [15], were recently detected in colorectal cancer samples via next-generation sequencing. These findings suggest that a previously unrecognized ALK fusion subset may be overlooked by the existing FISH, RT-PCR, and IHC detection methods. Thus, whether the low frequency of ALK fusion is due to insufficiently sensitive detection methods or its inherent qualities remains to be determined. Although we found that 8 out of 98 samples (8.2 %) exhibited ROS1 IHC 3+, none of our samples were FISH positive. In contrast, it has been reported that rabbit monoclonal ROS antibodies (clone D4D6; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA) showed 100 % sensitivity and 93.4 % specificity for predicting ROS1 rearrangement in lung cancer [13]. It seems plausible that the rabbit monoclonal antibody is superior to the rabbit polyclonal antibody we used in this study. However, additional reasons for the lower prevalence of ROS1 rearrangement may contribute to different tumor types. Another study that used the same ROS1 antibody as our current study found that 23 out of 495 gastric cancer samples (4.6 %) exhibited IHC 3+. Nonetheless, the incidence of ROS1 rearrangement based on ROS1 break-apart FISH is estimated to be only 0.6 % (3/495) [18]. All of these data show that ROS1 and ALK rearrangements remain barely detectable in gastrointestinal tumors.

In conclusion, our current analyses reveal associations between the oncogenic drivers MET, ROS1, and ALK and the response of gastric cancer cells to the potent small molecule inhibitor crizotinib both in vitro and in vivo. Significantly, we also investigated MET, ROS1, and ALK gene amplifications in a cohort of gastric cancer patients. We found that crizotinib may induce clinically relevant anticancer effects in MET-overexpressing and MET-amplified gastric cancer patients.

References

Kim JW, Im SA, Kim M, Cha Y, Lee KH, Keam B, et al. The prognostic significance of HER2 positivity for advanced gastric cancer patients undergoing first-line modified FOLFOX-6 regimen. Anticancer Res. 2012;32:1547–53.

Janjigian YY, Werner D, Pauligk C, Steinmetz K, Kelsen DP, Jager E, et al. Prognosis of metastatic gastric and gastroesophageal junction cancer by HER2 status: a European and USA international collaborative analysis. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:2656–62.

Bang YJ, Van Cutsem E, Feyereislova A, Chung HC, Shen L, Sawaki A, et al. Trastuzumab in combination with chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for treatment of HER2-positive advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer (ToGA): a phase 3, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet (London, England). 2010;376:687–97.

Gravalos C, Jimeno A. HER2 in gastric cancer: a new prognostic factor and a novel therapeutic target. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:1523–9.

Hofmann M, Stoss O, Shi D, Buttner R, van de Vijver M, Kim W, et al. Assessment of a HER2 scoring system for gastric cancer: results from a validation study. Histopathology. 2008;52:797–805.

Tanner M, Hollmen M, Junttila TT, Kapanen AI, Tommola S, Soini Y, et al. Amplification of HER-2 in gastric carcinoma: association with Topoisomerase IIalpha gene amplification, intestinal type, poor prognosis and sensitivity to trastuzumab. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:273–8.

Shaw AT, Yeap BY, Solomon BJ, Riely GJ, Gainor J, Engelman JA, et al. Effect of crizotinib on overall survival in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring ALK gene rearrangement: a retrospective analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:1004–12.

Kwak EL, Bang YJ, Camidge DR, Shaw AT, Solomon B, Maki RG, et al. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase inhibition in non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1693–703.

Shaw AT, Solomon BJ. Crizotinib in ROS1-rearranged non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:683–4.

Ou SH, Kwak EL, Siwak-Tapp C, Dy J, Bergethon K, Clark JW, et al. Activity of crizotinib (PF02341066), a dual mesenchymal-epithelial transition (MET) and anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) inhibitor, in a non-small cell lung cancer patient with de novo MET amplification. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:942–6.

Kutok JL, Aster JC. Molecular biology of anaplastic lymphoma kinase-positive anaplastic large-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:3691–702.

George RE, Sanda T, Hanna M, Frohling S, Luther W 2nd, Zhang J, et al. Activating mutations in ALK provide a therapeutic target in neuroblastoma. Nature. 2008;455:975–8.

Cha YJ, Lee JS, Kim HR, Lim SM, Cho BC, Lee CY, et al. Screening of ROS1 rearrangements in lung adenocarcinoma by immunohistochemistry and comparison with ALK rearrangements. PLoS One. 2014;9:e103333.

Fukuyoshi Y, Inoue H, Kita Y, Utsunomiya T, Ishida T, Mori M. EML4-ALK fusion transcript is not found in gastrointestinal and breast cancers. Br J Cancer. 2008;98:1536–9.

Lee J, Kim HC, Hong JY, Wang K, Kim SY, Jang J, et al. Detection of novel and potentially actionable anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) rearrangement in colorectal adenocarcinoma by immunohistochemistry screening. Oncotarget. 2015;6(27):24320–32.

Davies KD, Doebele RC. Molecular pathways: ROS1 fusion proteins in cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:4040–5.

Gu TL, Deng X, Huang F, Tucker M, Crosby K, Rimkunas V, et al. Survey of tyrosine kinase signaling reveals ROS kinase fusions in human cholangiocarcinoma. PLoS One. 2011;6:e15640.

Lee J, Lee SE, Kang SY, Do IG, Lee S, Ha SY, et al. Identification of ROS1 rearrangement in gastric adenocarcinoma. Cancer. 2013;119:1627–35.

Lennerz JK, Kwak EL, Ackerman A, Michael M, Fox SB, Bergethon K, et al. MET amplification identifies a small and aggressive subgroup of esophagogastric adenocarcinoma with evidence of responsiveness to crizotinib. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4803–10.

Chi AS, Batchelor TT, Kwak EL, Clark JW, Wang DL, Wilner KD, et al. Rapid radiographic and clinical improvement after treatment of a MET-amplified recurrent glioblastoma with a mesenchymal-epithelial transition inhibitor. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:e30–3.

Nakajima M, Sawada H, Yamada Y, Watanabe A, Tatsumi M, Yamashita J, et al. The prognostic significance of amplification and overexpression of c-met and c-erb B-2 in human gastric carcinomas. Cancer. 1999;85:1894–902.

Hara T, Ooi A, Kobayashi M, Mai M, Yanagihara K, Nakanishi I. Amplification of c-myc, K-sam, and c-met in gastric cancers: detection by fluorescence in situ hybridization. Lab Invest J Tech Methods Pathol. 1998;78:1143–53.

Tsugawa K, Yonemura Y, Hirono Y, Fushida S, Kaji M, Miwa K, et al. Amplification of the c-met, c-erbB-2 and epidermal growth factor receptor gene in human gastric cancers: correlation to clinical features. Oncology. 1998;55:475–81.

Liu YJ, Shen D, Yin X, Gavine P, Zhang T, Su X, et al. HER2, MET and FGFR2 oncogenic driver alterations define distinct molecular segments for targeted therapies in gastric carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:1169–78.

Huang TJ, Wang JY, Lin SR, Lian ST, Hsieh JS. Overexpression of the c-met protooncogene in human gastric carcinoma—correlation to clinical features. Acta Oncol (Stockholm, Sweden). 2001;40:638–43.

Janjigian YY, Tang LH, Coit DG, Kelsen DP, Francone TD, Weiser MR, et al. MET expression and amplification in patients with localized gastric cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20:1021–7.

Okamoto W, Okamoto I, Yoshida T, Okamoto K, Takezawa K, Hatashita E, et al. Identification of c-Src as a potential therapeutic target for gastric cancer and of MET activation as a cause of resistance to c-Src inhibition. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9:1188–97.

Zimmermann KC, Sarbia M, Weber AA, Borchard F, Gabbert HE, Schror K. Cyclooxygenase-2 expression in human esophageal carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1999;59:198–204.

Koeppen H, Yu W, Zha J, Pandita A, Penuel E, Rangell L, et al. Biomarker analyses from a placebo-controlled phase II study evaluating erlotinib±onartuzumab in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: MET expression levels are predictive of patient benefit. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:4488–98.

Bergethon K, Shaw AT, Ou SH, Katayama R, Lovly CM, McDonald NT, et al. ROS1 rearrangements define a unique molecular class of lung cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:863–70.

Li Y, Pan Y, Wang R, Sun Y, Hu H, Shen X, et al. ALK-rearranged lung cancer in Chinese: a comprehensive assessment of clinicopathology, IHC, FISH and RT-PCR. PloS One. 2013;8:e69016.

Gavine PR, Ren Y, Han L, Lv J, Fan S, Zhang W, et al. Volitinib, a potent and highly selective c-Met inhibitor, effectively blocks c-Met signaling and growth in c-MET amplified gastric cancer patient-derived tumor xenograft models. Mol Oncol. 2015;9:323–33.

Matsumoto K, Nakamura T. Emerging multipotent aspects of hepatocyte growth factor. J Biochem. 1996;119:591–600.

Humphrey PA, Zhu X, Zarnegar R, Swanson PE, Ratliff TL, Vollmer RT, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor and its receptor (c-MET) in prostatic carcinoma. Am J Pathol. 1995;147:386–96.

Iveson T, Donehower RC, Davidenko I, Tjulandin S, Deptala A, Harrison M, et al. Rilotumumab in combination with epirubicin, cisplatin, and capecitabine as first-line treatment for gastric or oesophagogastric junction adenocarcinoma: an open-label, dose de-escalation phase 1b study and a double-blind, randomised phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:1007–18.

Zhu M, Tang R, Doshi S, Oliner KS, Dubey S, Jiang Y, et al. Exposure-response analysis of rilotumumab in gastric cancer: the role of tumour MET expression. Br J Cancer. 2015;112:429–37.

Marano L, Chiari R, Fabozzi A, De Vita F, Boccardi V, Roviello G, et al. c-Met targeting in advanced gastric cancer: an open challenge. Cancer Lett. 2015;365:30–6.

Kawakami H, Okamoto I, Arao T, Okamoto W, Matsumoto K, Taniguchi H, et al. MET amplification as a potential therapeutic target in gastric cancer. Oncotarget. 2013;4:9–17.

Appleman LJ. MET signaling pathway: a rational target for cancer therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4837–8.

Solomon BJ, Mok T, Kim DW, Wu YL, Nakagawa K, Mekhail T, et al. First-line crizotinib versus chemotherapy in ALK-positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:2167–77.

Shaw AT, Kim DW, Nakagawa K, Seto T, Crino L, Ahn MJ, et al. Crizotinib versus chemotherapy in advanced ALK-positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2385–94.

Mescam-Mancini L, Lantuejoul S, Moro-Sibilot D, Rouquette I, Souquet PJ, Audigier-Valette C, et al. On the relevance of a testing algorithm for the detection of ROS1-rearranged lung adenocarcinomas. Lung Cancer (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2014;83:168–73.

Kwon KJ, Shim KN, Song EM, Choi JY, Kim SE, Jung HK, et al. Clinicopathological characteristics and prognosis of signet ring cell carcinoma of the stomach. Gastric Cancer. 2014;17:43–53.

Houang M, Toon CW, Clarkson A, Sioson L, de Silva K, Watson N, et al. ALK and ROS1 overexpression is very rare in colorectal adenocarcinoma. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2015;23:134–8.

Miller J, Peng Z, Wilcox R, Evans M, Ades S, Verschraegen C. Absence of anaplastic lymphoma kinase translocations in signet ring cell carcinomas of the upper gastrointestinal tract. Gastrointest Cancer Res. 2014;7:39–41.

Lipson D, Capelletti M, Yelensky R, Otto G, Parker A, Jarosz M, et al. Identification of new ALK and RET gene fusions from colorectal and lung cancer biopsies. Nat Med. 2012;18:382–4.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 81220108023, 81370064, 81572329), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (20620140729), Jiangsu Provincial Program of Medical Science (BL2012001), and the Distinguished Young Investigator Project of Nanjing (JQX12002). The funding sources had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest to disclose.

Ethical statement

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and later versions. Informed consent or a substitute for it was obtained from all patients before they were included in the study. Meanwhile, all institutional and national guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals were followed.

Additional information

Y. Yang and N. Wu contributed equally to this work.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, Y., Wu, N., Shen, J. et al. MET overexpression and amplification define a distinct molecular subgroup for targeted therapies in gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer 19, 778–788 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-015-0545-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-015-0545-5