Abstract

Background and aims

Pathological studies indicate papillary adenocarcinomas are more aggressive than tubular adenocarcinomas, but a definitive diagnosis is difficult using conventional endoscopy alone. The vessels within an epithelial circle (VEC) pattern, visualized using magnifying endoscopy with narrow-band imaging (ME-NBI), may be a feature of papillary adenocarcinoma. The aims of our study were to investigate whether the VEC pattern is useful in the preoperative diagnosis of papillary adenocarcinoma and to determine whether VEC-positive adenocarcinomas are more malignant than VEC-negative lesions.

Patients and materials

From 395 consecutive early gastric cancers resected using the endoscopic submucosal dissection method, we analyzed 35 VEC-positive lesions and 70 VEC-negative control lesions matched for size and macroscopic type. We evaluated (1) the correlation between the incidence of VEC-positive cancers and the histological papillary structure and (2) differences in the incidence of coexisting undifferentiated carcinoma in VEC-positive and VEC-negative cancers and the incidence of submucosal and vascular invasion.

Results

Histological papillary structure was seen in 94 % (33/35) of VEC-positive and 9 % (6/70) of VEC-negative cancers, a significant difference (P < 0.001). The incidence of coexisting undifferentiated carcinoma was 23 % (8/35) in VEC-positive and 3 % (2/70) in VEC-negative cancers (P = 0.002). The incidence of submucosal invasion by the carcinoma was 26 % (9/35) in VEC-positive cancers and 10 % (7/70) in VEC-negative cancers (P = 0.045).

Conclusions

The VEC pattern as visualized using ME-NBI is a promising preoperative diagnostic marker of papillary adenocarcinoma. Coexisting undifferentiated carcinoma and submucosal invasion were each seen in approximately one fourth of VEC-positive cancers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background and aims

Papillary adenocarcinoma is a structural subtype of adenocarcinoma described in the World Health Organization (WHO) classification [1]. Basically, it is categorized as a structural subtype of differentiated cancer, together with tubular adenocarcinoma. Various histological studies have reported that papillary adenocarcinoma shows a higher degree of malignancy than tubular adenocarcinoma [2–9].

Specifically, rates of liver metastasis [2, 4, 5], lymph node metastasis [2–4, 6–8], and vascular invasion [8, 9], are reported to be higher for papillary adenocarcinoma than tubular adenocarcinoma. In some cases, during the growth phase both structural types have been reported to transform into undifferentiated carcinoma [2]. Furthermore, compared with tubular adenocarcinomas, papillary adenocarcinomas have a lower postoperative survival rate and poorer life expectancy [5, 6].

Comparison with tubular adenocarcinoma in this way indicates that papillary adenocarcinoma clearly shows more malignant biological behavior, sounding alarms that clinically it needs to be handled with care. However, it is not possible to make a preoperative diagnosis of papillary adenocarcinoma using conventional endoscopy.

We previously reported that magnifying endoscopy with narrow-band imaging (ME-NBI) enables endoscopists to diagnose early gastric cancer more accurately than with conventional endoscopy, because ME-NBI can visualize the microanatomy of the superficial part of the gastric mucosa [10–14]. In addition, we reported the characteristic findings of papillary adenocarcinoma as visualized using ME-NBI, with vessels within the circular intervening part surrounded by circular marginal crypt epithelium, that we have labeled the vessels within epithelial circle (VEC) pattern [15, 16]. However, no studies have systematically evaluated the usefulness of the VEC pattern in diagnosing papillary adenocarcinoma. The first aim of this study was to evaluate whether the VEC pattern is useful in the preoperative diagnosis of papillary adenocarcinoma, and the second aim was to compare and evaluate differences in the degree of malignancy between VEC-positive and VEC-negative early gastric cancers.

Materials and methods

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Early gastric cancers satisfying all the following inclusion and exclusion criteria were included in this study and analyzed. All study participants gave informed consent, and the study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Fukuoka University Chikushi Hospital.

Inclusion criteria

-

1.

Consecutive early gastric cancers endoscopically resected en bloc at Fukuoka University Chikushi Hospital between January 2006 and November 2011, for which detailed histopathological examination was possible.

-

2.

Lesions diagnosed as differentiated cancers through histopathological examination of preoperative biopsy specimens.

Exclusion criteria

-

1.

Lesions that could not be visualized using ME-NBI.

-

2.

Lesions diagnosed as undifferentiated carcinoma through histopathological examination of preoperative biopsy specimens.

-

3.

Lesions not biopsied preoperatively.

Endoscopic procedure

Endoscopies were performed by two experienced endoscopists (K.Y. and T.N.), who are familiar with this procedure and ME-NBI, using a high-resolution magnifying upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscope (GIF-Q240Z; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) or a high-definition magnifying upper GI endoscope (GIF-H260Z; Olympus), and an electronic endoscopy system (Evis Lucera Spectrum; Olympus), as described previously [10–14]. Before the examination, a soft black hood is mounted on the tip of the endoscope to enable the endoscopist to consistently fix the mucosa at a distance of approximately 2 mm, at which maximal magnification of the endoscopic image can be obtained. Because the tip of the hood is soft, it does not injure the mucosa. The lesion is visualized employing incremental movements of the tip of the endoscope to bring the image into focus, with a distally attached soft black hood to stabilize the tip of the endoscope without causing mucosal injury [10].

Definition of VEC pattern

We have defined the VEC pattern as the ME-NBI findings of vessels within the circular intervening part surrounded by circular marginal crypt epithelium (Fig. 1a–c). When a VEC pattern is seen in any part of a lesion, it is assessed as VEC positive. When no areas with a VEC pattern can be discerned within the area examined, it is assessed as VEC negative (Fig. 2a–c).

a Conventional white light imaging findings of early gastric cancer (0-IIa type). A superficial elevated lesion (arrow) is present on the lesser curvature of the gastric antrum. b ME-NBI findings. Within the demarcation line (arrows), the vessels within an epithelial circle (VEC) pattern can be seen. An irregular microvascular pattern is observed in the circular intervening part between crypts lined by circular marginal crypt epithelium. c ME-NBI findings. The circular marginal crypt epithelium has been traced. We can clearly see that blood vessels are present beneath the circular intervening part between crypts lined by circular marginal crypt epithelium. When a VEC pattern is seen in any part of a lesion, it is assessed as VEC pattern positive

a Conventional white light imaging findings of early gastric cancer (0-IIa type). A superficial elevated lesion (arrow) is present on the anterior wall of the gastric antrum. b ME-NBI findings. Within the demarcation line (arrows), a VEC pattern cannot be identified. c Magnifying endoscopy with narrow-band imaging (ME-NBI) findings. The marginal crypt epithelium has been traced, delineating its relationship with the vessels (arrows). The marginal crypt epithelium has a curved rather than circular morphology. Accordingly, no circular intervening parts can be visualized, and there is no consistent pattern to the epithelial and vascular patterns: this is therefore VEC pattern negative

VEC-positive pattern designation

As visualized by ME-NBI, when the lesion exhibited vessels within an epithelial circle surrounded by circular marginal crypt epithelium, it was assessed as a VEC-positive pattern (Fig. 1a–c) and assigned to the VEC-positive group. All lesions included in this study were reviewed using ME-NBI to determine whether a VEC pattern was present. If a VEC pattern was observed in any part of a lesion, it was assessed as a VEC-positive pattern.

VEC-negative pattern (control) designation

From the VEC-negative early gastric cancers as visualized using ME-NBI (Fig. 2a–c), for each VEC-positive early gastric cancer we selected two lesions with the same diameter and macroscopic type to serve as VEC-negative controls.

Endoscopic diagnosis

In this study, all ME-NBI findings were reviewed retrospectively by one endoscopist (K.Y., 13 years experience with upper gastrointestinal magnifying endoscopy), who was blinded to the histological findings, to determine whether they were VEC pattern positive or negative. Another endoscopist blinded to the independent histological findings (T.N., 8 years experience with upper gastrointestinal magnifying endoscopy) also read all endoscopic images placed in random order, to determine whether they were VEC pattern positive or negative, based on the VEC pattern definition. When the VEC pattern findings by the two endoscopists were not in agreement, we used the findings by K.Y. in light of his greater experience with ME-NBI. We then determined the interobserver variability for K.Y. and T.N.

Histopathological examination

Resected specimens obtained by ESD were stretched out and pinned onto a rubber plate. After fixation for 24 h in 20 % formalin solution, the specimen was sliced at 2-mm intervals. Each slice was coated in paraffin, then sliced into thicknesses of 5 μm, stained with hematoxylin and eosin, then histopathologically examined. Examinations were made by a pathologist (T.K.) blinded to the endoscopic findings.

Histological definition of papillary structure

In this study, the authors histopathologically defined the papillary structure as follows:

-

1.

Well-differentiated exophytic carcinoma with elongated finger-like processes lined by cylindrical or cuboidal cells supported by a fibrovascular connective tissue core (Fig. 3a).

Fig. 3 a Histopathological findings. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain, ×40). Well-differentiated exophytic carcinoma with elongated finger-like processes lined by cylindrical or cuboidal cells supported by a fibrovascular connective tissue core. b Histopathological findings. H&E stain, ×40. Cross-section view of a well-differentiated adenocarcinoma with a papillary structure shows a core of interstitial tissue lined by circular epithelium

-

2.

Cross section of well-differentiated adenocarcinoma with papillary structure of exophytic carcinoma with elongated and separate finger-like processes (Fig. 3b).

Lesions that exhibited features 1 and 2 were defined as papillary structure positive.

Assessed items

The VEC-positive group and VEC-negative groups were histopathologically assessed for the following endpoints.

Primary endpoint

Difference in the incidence of histological papillary structure in the VEC-positive and VEC-negative groups.

Secondary endpoints

-

1.

Difference in the incidence of coexisting histologically undifferentiated carcinoma in the VEC-positive and VEC-negative groups.

-

2.

Difference in the incidence of submucosal invasion by the carcinoma in the VEC-positive and VEC-negative groups.

-

3.

Difference in the incidence of lymphatic invasion by cancer in VEC-positive and VEC-negative groups.

-

4.

Difference in the incidence of vascular invasion by cancer in VEC-positive and VEC-negative groups.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables, presented as mean ± SD, were compared using Student’s t test. Categorical variables were compared using Fisher’s exact test. P values less than 0.05 were considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed using the statistical software package SPSS 16.0 for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

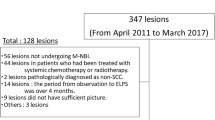

Analysis groups (Fig. 4)

Between January 2006 and November 2011, our Department excised 430 early gastric cancers using ESD in 365 patients. We excluded 35 lesions, comprising 21 lesions diagnosed as undifferentiated carcinoma on preoperative histological examination, 10 lesions not examined using ME-NBI, and 4 lesions not biopsied preoperatively. Accordingly, this study examined 395 lesions from 338 patients. On ME-NBI examination, 35 lesions in 33 patients were classified as VEC positive; there were 360 VEC-negative early gastric cancers. From these, 70 early gastric cancers from 67 patients were selected, matched for size and macroscopic type to VEC-positive lesions.

Clinical characteristics

Table 1 shows the clinical characteristics of patients with VEC-positive and VEC-negative cancers. No significant differences were seen between the two groups in any parameters.

Primary endpoint

The frequency of the histological papillary structure (Table 2) was 94.3 % (33/35) for VEC-positive lesions and 8.6 % (6/70) for VEC-negative lesions. The VEC pattern as detected using ME-NBI showed an extremely strong correlation with the presence of a histological papillary structure (P < 0.001). The VEC pattern detected by ME-NBI examination produced results of 84.6 % (33/39), 96.9 % (64/66), 94.2 % (33/35), and 91.4 % (64/70), respectively, for sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value for the diagnosis of papillary structure. The interobserver agreement rate for K.Y. and T.N. was 99 % (104/105), yielding a κ value of 0.96 (almost perfect agreement).

Secondary endpoints

-

1.

The frequency of coexisting undifferentiated carcinoma was 22.9 % (8/35) in the VEC-positive group and 2.9 % (2/70) in the VEC-negative group (Table 2). In other words, coexisting undifferentiated carcinoma was significantly more common in the VEC-positive than the VEC-negative group (P = 0.002). The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value for coexisting undifferentiated carcinoma in VEC-positive gastric cancers were 80.0 % (8/10), 71.6 % (68/95), 22.9 % (8/35), and 97.1 % (68/70), respectively.

-

2.

The frequency of submucosal invasion was 25.7 % (9/35) in the VEC-positive group, and 10 % (7/70) in the VEC-negative group (Table 2). In other words, submucosal invasion was significantly more common in the VEC-positive than the VEC-negative group (P = 0.045) (Fig. 5a–d).

Fig. 5 a Conventional white light imaging findings of early gastric cancer (0-IIa type). A superficial elevated lesion (arrow) is present on the lesser curvature of the gastric antrum. b ME-NBI findings. Within the demarcation line (yellow arrows), a VEC pattern (white arrows) can be seen in this carcinoma. c Histopathological findings. H&E stain, ×20. The surface part of the lesion shows cancerous tissue with a papillary structure. In the deep submucosa, the degree of differentiation decreases, and invasion of the submucosa is accompanied by a large quantity of mucus. d Histopathological findings. H&E stain, ×200. Signet-ring cells can be seen in the deep layers of the mucosa

-

3.

The frequency of lymphatic invasion was 22.9 % (8/35) in the VEC-positive group, and 10 % (7/70) in the VEC-negative group (Table 2). No significant difference was seen between groups (P = 0.086).

-

4.

The frequency of vascular invasion (Table 2) was 2.9 % (1/35) in the VEC-positive group, and 1.4 % (1/70) in the VEC-negative group, with no significant difference seen between groups (P > 0.999).

Discussion

The results of this study demonstrated that the VEC pattern as detected using ME-NBI is an extremely effective marker for the diagnosis of the histological papillary structure. It was not clear before this study whether the histological papillary structure could be diagnosed preoperatively from the endoscopic findings alone. As shown in Fig. 6, the circular intervening part surrounded by circular marginal crypt epithelium visualized using ME-NBI is thought to correspond histologically to the papillary intervening part. The ME-NBI findings of microvessels within the epithelial circle are thought to correspond histologically to vessels proliferating within the stroma of the narrow intervening part with a histological papillary structure. Although few in number, there were some exceptions. In two lesions, the histological papillary structure was not seen despite a VEC-positive pattern. When the ME-NBI findings of these two lesions were reviewed in detail, it was determined that only a small part of the lesion exhibited the VEC pattern. Accordingly, the reason why the papillary structure could not be histologically proven was thought to be that the part containing the histological papillary structure corresponding to the VEC pattern was not included in the sections actually examined histologically.

Relationship between the VEC pattern and the histopathological papillary structure. Upper image shows VEC pattern as visualized using ME-NBI; lower image shows the histological findings corresponding to the VEC pattern. The circular intervening part surrounded by circular marginal crypt epithelium visualized using ME-NBI corresponds histologically to the papillary intervening part. Microvessels within epithelial circles as visualized using ME-NBI correspond histologically to vessels proliferating beneath the intervening part epithelium. MCE marginal crypt epithelium, IP intervening part

Conversely, in six lesions the histological papillary structure was recognized despite a VEC-negative pattern. Of these, three lesions were macroscopically type 0-I located in the gastric antrum. ME-NBI generally does not permit adequate observation on the anal side of raised lesions in the gastric antrum. Accordingly, limitation of the field of view was considered the reason the VEC pattern could not be detected. For two lesions, the reason was considered to be that the tumor diameters were large at 115 and 47 mm. When the ME-NBI images of these lesions were reviewed, the entire margin of each lesion was examined under magnification, but the central part of the lesion was not. Furthermore, histologically the lesion margins consisted entirely of tubular adenocarcinoma. Accordingly, the fact that the central part containing the histological papillary structure was not examined using ME-NBI was considered the cause for the false-negative result. For the remaining lesion, the VEC pattern was overlooked at the ME-NBI examination. In other words, following the histological findings, when the ME-NBI images were reviewed in detail, a single area with a VEC pattern was recognized.

To clarify the differences in malignancy potential between VEC-positive and VEC-negative patterns, we performed further histological evaluations.

The frequency of coexisting undifferentiated carcinoma was significantly higher at 22.9 % in the VEC-positive than in the VEC-negative group. Accordingly, under ME-NBI examination, approximately one fourth of VEC-positive carcinomas contain coexisting undifferentiated carcinoma, indicating a higher degree of malignancy than other differentiated gastric cancers.

The frequency of submucosal invasion in the VEC-positive pattern was also significantly higher at 25.7 % in the VEC-positive than in the VEC-negative group. Accordingly, VEC-positive carcinomas are considered to have higher invasive potential than VEC-negative carcinomas.

No significant difference was found between the VEC-positive and VEC-negative groups in the rates of lymphatic and vascular invasion. Among intramucosal carcinomas, Hirota et al. [5] reported no significant differences in lymphatic metastatic rates between papillary and tubular adenocarcinomas. Because the lesions examined in the current study were clinically diagnosed as intramucosal carcinoma, inclusion of gastric cancers of all stages, as well as surgically removed lesions, might further elucidate this issue.

In general, papillary adenocarcinoma as a structural type is diagnosed when papillary components are seen to be dominant. Ito et al. [8] reported that malignancy was stronger in differentiated gastric cancers that included some component of papillary adenocarcinoma, even if it was not the dominant structural type. In this study, we have assessed it as a VEC-positive pattern when a VEC pattern was recognized in any part of the lesion. Accordingly, the results of this study strongly agree with those of Ito et al.

This was designed as a case-controlled retrospective study. To minimize sampling bias, we selected as a control group VEC-negative early gastric cancers of the same diameter and macroscopic type. The reason for selecting the same tumor diameters was reports that the malignancy of gastric cancers depends on their size. Otsuji et al. [17] reported, for early gastric cancers, that a diameter of 4 cm or more was a risk factor for lymphatic metastasis. The reason for selecting the same macroscopic type was that it has been reported that the protruded type and superficial elevated type are common among papillary adenocarcinomas. Koseki et al. [9] reported that compared to tubular adenocarcinomas, papillary adenocarcinomas have more type 0-I (protruded type) and type 0-IIa (superficial elevated type), and less depressed type.

One limitation of this study is that we examined early gastric cancers excised using ESD. The reason for this is that in our Department of Endoscopy, ESD is indicated in all early gastric cancers, and ME-NBI is used to visualize the lesion over its entire circumference and delineate the margins, as we previously reported [12]. However, lesions indicated for surgical resection, where the carcinoma has invaded deeper than the submucosal layer, are not examined in detail using magnified endoscopy. Accordingly, this study studied only early gastric cancers clinically diagnosed as intramucosal carcinoma. In the future, to accurately evaluate the degree of malignancy of VEC-positive gastric cancers, it will be necessary to study gastric cancers of all stages, including those indicated for surgical resection. However, the results of this study, obtained just from cancers clinically diagnosed as intramucosal carcinomas, indicate that VEC-positive early gastric carcinomas have a higher degree of malignancy and an increased risk of submucosal invasion. We anticipate that further studies comparing gastric cancers at more advanced stages with submucosal carcinomas will demonstrate an increased degree of malignancy and risk of invasion for VEC-positive gastric cancers. Another limitation of this study was that we were unable to compare all endoscopic images with their corresponding histological findings. In a future study, we need to mark the vicinity of any areas with a VEC pattern visualized using ME-NBI and determine whether the VEC pattern corresponds to the histological papillary structure.

In clinical practice, the presence of a VEC pattern is a warning sign that can be part of a preoperative assessment strategy for early gastric cancer. If a VEC pattern is detected using ME-NBI, we recommend further investigations. To determine the horizontal extent of undifferentiated carcinoma, we recommend taking multiple biopsies because chromoendoscopy and ME-NBI are of limited diagnostic value in cases of undifferentiated carcinoma, as previously reported [12, 18]. Accordingly, even when the preoperative histological diagnosis from a biopsy specimen is of differentiated carcinoma, we should take multiple biopsies from the apparently nonneoplastic mucosa to confirm histologically that there are no cancerous cells as soon as we detect a VEC pattern using ME-NBI. In addition, we should make an accurate diagnosis of the depth of submucosal invasion using endoscopic ultrasound [18], because the VEC pattern is a warning sign for possible invasive cancer.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that for early gastric cancers diagnosed preoperatively as differentiated carcinoma by histological investigation of biopsy specimens, the VEC pattern as visualized by ME-NBI is useful in diagnosing the histological papillary structure. Furthermore, coexisting undifferentiated carcinoma and submucosal invasion were each seen in approximately one fourth of VEC-positive early gastric cancers, indicating that the VEC pattern can become an effective marker for the preoperative prediction of a high degree of malignancy in cancers. In future, it will be necessary to perform a prospective evaluation of multiple cases of gastric carcinoma, including all stages, to elucidate the clinical significance of the VEC pattern as a marker.

References

Lauwers GY, Carnerio F, Graham DY, et al. Tumours of the stomach. In: Bosman FT, Carnerio F, Hruban RH, editors. WHO classification of tumors of the digestive system. Lyon: IARC; 2010. p. 46–80.

Kaibara N, Kimura O, Nishidoi H, et al. High incidence of liver metastases in gastric cancer with medullary growth pattern. J Surg Oncol. 1985;28:195–8.

Mita T, Shimoda T. Risk factors for lymph node metastasis of submucosal invasive differentiated type gastric carcinoma: clinical significance of histological heterogeneity. J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:661–8.

Yasuda K, Adachi Y, Shiraishi N, et al. Papillary adenocarcinoma of the stomach. Gastric Cancer. 2000;3:33–8.

Hirota T, Ochiai A, Itabashi M, et al. Significance of histopathological type of gastric carcinoma as a prognostic factor [in Japanese with English abstract]. Stomach Intest. 1991;26:1149–58.

Uefuji K, Ichikura T, Tamakuma S. Clinical and prognostic characteristics of papillary clear cell carcinoma of stomach. Jpn J Surg. 1996;26:15–163.

Ito E, Takizawa T. Differentiated adenocarcinoma of the gastric and intestinal phenotype: histological appearance and biological behavior [in Japanese with English abstract]. Stomach Intest. 2003;38:701–6.

Ito T, Takizawa T, Horiguchi S, et al. Gastric adenocarcinoma with submucosal invasion: histological appearance and biological behavior [in Japanese with English abstract]. Stomach Intest. 2007;42:7–13.

Koseki K, Takizawa T, Koike M, et al. Distinction of differentiated type early gastric carcinoma with gastric type mucin expression. Cancer (Phila). 2000;89:724–32.

Yao K, Anagnostopoulos GK, Ragunath K. Magnifying endoscopy for diagnosing and delineating early gastric cancer. Endoscopy. 2009;41:462–7.

Yao K, Iwashita A, et al. White opaque substance within superficial elevated gastric neoplasia as visualized by magnification endoscopy with narrow-band imaging: a new optical sign for differentiating between adenoma and carcinoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:574–9.

Nagahama T, Yao K, Maki S, et al. Usefulness of magnifying endoscopy with narrow-band imaging for determining the horizontal extent of early gastric cancer when there is an unclear margin by chromoendoscopy (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:1259–67.

Ezoe Y, Muto M, Uedo N, et al. Magnifying narrowband imaging is more accurate than conventional white-light imaging in diagnosis of gastric mucosal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:2017–25.

Maki S, Yao K, Nagahama T, et al. Magnifying endoscopy with narrow-band imaging is useful in the differential diagnosis between low-grade adenoma and early cancer of superficial elevated gastric lesions. Gastric Cancer. 2013;16:140–6.

Yao K. VS classification for the diagnosis of early gastric cancer (in Japanese). In: Yao K, editor. Magnifying endoscopy in the stomach. Tokyo: Nihon Medical Center; 2009. p. 107–81.

Uedo N. Early gastric cancer (differentiated type): 0-IIc (in Japanese). In: Muto M, Yao K, Sano Y, editors. The atlas of endoscopy with narrow band imaging. Tokyo: Nankodo; 2011. p. 166–7.

Otsuji E, Ichikawa D, Ochiai T, et al. Prediction of lymph node metastasis by size of early gastric carcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology. 2007;54:602–5.

Yao K, Nagahama T, Matsui T, et al. Detection and characterization of early gastric cancer for curative endoscopic submucosal dissection. Dig Endosc. 2013;25(suppl 1):44–54.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Uedo (Department of Gastrointestinal Oncology, Osaka for Cancer and Cardiovascular Diseases, Osaka Japan) for valuable academic contributions, and Dr. Mark Preston (Access Medical Communications) for correcting the English used in this manuscript. This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (# 21590882), and funding from the Central Research Institute of Fukuoka University (I) and Central Research Institute of Fukuoka University for Endoscopy.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kanemitsu, T., Yao, K., Nagahama, T. et al. The vessels within epithelial circle (VEC) pattern as visualized by magnifying endoscopy with narrow-band imaging (ME-NBI) is a useful marker for the diagnosis of papillary adenocarcinoma: a case-controlled study. Gastric Cancer 17, 469–477 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-013-0295-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-013-0295-1