Abstract

Background

Early esophagogastric junction (EGJ) cancer is currently being treated in the same way as early gastric cancer, by endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), but long-term outcomes are still unknown. Our aim was to retrospectively evaluate the safety and efficacy of ESD in treating early EGJ cancer and compare risk factors in curative and non-curative resection cases.

Methods

Forty-four cases of early EGJ cancer, defined as a Siewert’s type II tumor, in 44 patients with a mean age of 70.0 years and a male/female ratio of 90.9:9.1 % were treated by ESD between January 2004 and June 2010. There were 30 standard indication cases; the remaining 14 cases were expanded indication cases.

Results

Mean resected specimen and tumor sizes were 35 and 17 mm, respectively, and median procedure time was 121 min, with no bleeding or perforation complications. All cases were resected en bloc with an 84.1 % curative resection rate (37/44). The curative resection rates in the standard and expanded indication cases were 90.0 % (27/30) and 71.4 % (10/14), respectively. There were no significant differences in tumor location, tumor morphology, tumor size, histology of biopsy specimens, or standard versus expanded indication cases with regard to risk factors for curative and non-curative resections. However, submucosal invasion, positive tumor margins, lymphovascular invasion, and some components of poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas in just the submucosal layer were significantly more common in the non-curative resection cases.

Conclusions

ESD was a safe, effective, and minimally invasive treatment for early EGJ cancer. For tumors without any submucosal invasion findings, therefore, ESD is an acceptable treatment option, in addition to also being suitable for diagnostic purposes in evaluating the need for surgery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The incidence of esophagogastric junction (EGJ) adenocarcinoma has increased considerably in the United States and other Western countries recently [1–4] and there is a good possibility of the incidence of such EGJ cancer increasing in Japan in the foreseeable future [5]. In Japan, early EGJ cancer is currently being treated by endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), in the same way as early gastric cancer [6–8], but long-term outcomes are still unknown. Our aim was to retrospectively evaluate the safety and efficacy of ESD in treating early EGJ cancer.

Patients and methods

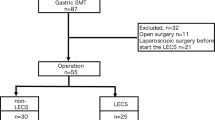

A total of 44 early EGJ cancers in 44 patients with a mean age of 70.0 years (range, 42–84) and a male/female ratio of 40: 4 (90.9:9.1 %) were treated by ESD between January 2004 and June 2010 at the Cancer Institute Hospital in Tokyo, Japan. EGJ cancer was defined as a type ΙΙ tumor according to Siewert’s classification, with the tumor center located within an area 1 cm above and 2 cm below the EGJ [9]. In an effort to clarify the clinical effectiveness of ESD for early EGJ cancer, we retrospectively investigated the clinical characteristics of the 44 patients and 44 early EGJ cancers, the ESD procedures that were performed, and the pathological features of the early EGJ cancers. We then assessed the complication, en-bloc resection, curative resection, local recurrence, and distant metastasis rates and compared risk factors in curative and non-curative resection cases to determine the long-term outcomes.

Indications for ESD

The indications for ESD were defined by the criteria of the Japan Gastric Cancer Association (JGCA) [10].

Standard guideline criteria for endoscopic resection

Differentiated adenocarcinoma or intramucosal cancer ≤20 mm in size without an ulcer finding.

Expanded indication criteria for endoscopic submucosal dissection

Differentiated adenocarcinoma regardless of tumor size with no apparent submucosal invasion finding and without an ulcer finding, or ≤30 mm in size with an ulcer finding.

Chromoendoscopy using indigo-carmine dye, magnification endoscopy with narrow-band imaging (ME-NBI), and circumferential lesion biopsies were used for determining lateral tumor margins, and endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) was performed for establishing invasion depth.

ESD procedures

The ESDs were performed by expert endoscopists certified by the Japan Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. The procedures were performed using an insulation-tipped knife (IT knife) (KD-610L; Olympus Optical, Tokyo, Japan) or an IT knife 2 (KD-611L; Olympus) and a single-channel upper gastrointestinal endoscope (GIF-Q260J, GIF-H260; Olympus) with a transparent hood (D-201-11804; Olympus) attached to the tip of the endoscope. An electrosurgical current was applied using a standard electrosurgical generator (VIO300D; ERBE, Tübingen, Germany, or ESG100; Olympus). All procedures were conducted in patients who received intravenous anesthesia using midazolam and pethidine hydrochloride. Tumor identification was followed by circumferential marking around the tumor, using argon plasma coagulation based on previous biopsy scarring (Fig. 1a, b). Glyceol® (10 % glycerol and 5 % fructose in a normal saline solution; Chugai Pharmaceutical, Tokyo, Japan) or hyaluronic acid (MucoUp®; Johnson & Johnson Japan, Tokyo, Japan) was then injected into the submucosal layer to lift the mucosa at the oral side of the tumor, using the retroflex view, because controlling the scope was difficult with the forward endoscopic view owing to the narrow lumen of the EGJ. An initial cut, referred to as a pre-cut incision, was made with a standard needle-knife on the oral side of the tumor, followed by a circumferential mucosa incision around the tumor, using the IT knife or IT knife 2 (Fig. 1c–e). The tumor was then completely removed by submucosal dissection, using the IT knife or IT knife 2, performed from the anal side of the tumor, using the retroflex view (Fig. 1f).

Endoscopic submucosal dissection procedure. a Reddish elevated tumor located at the esophagogastric junction (EGJ). b Circumferential marking performed around the tumor, using argon plasma coagulation based on previous biopsy scarring. c Hyaluronic acid injected into the submucosal layer to lift the mucosa at the oral side of the tumor, using retroflex view. Pre-cut incision made with standard needle-knife on the oral side of the tumor. d Circumferential mucosa incision around the tumor made using an insulation-tipped knife (IT knife; KD-610L; Olympus Optical) or an IT knife 2 (KD-611L; Olympus). e Submucosal dissection using IT knife or IT knife 2 performed from the anal side of the tumor using retroflex view. f Completely resected tumor

Pathological assessment of resected specimens

Early EGJ cancers were categorized according to location, i.e., the anterior wall (AW), greater curvature, posterior wall (PW), and lesser curvature (LC). The Paris endoscopic classification of superficial neoplastic lesions was used to characterize the surface morphology of the tumors [11]. Resected specimens were mounted on boards with pins and fixed in 10 % formalin for 24 h. After fixation, all resected specimens were cut into longitudinal slices 2 mm in width and then embedded in paraffin and stained with hematoxylin–eosin. Pathological assessments, including tumor size, depth of invasion, and the presence of lymphovascular invasion, were performed microscopically. Based on these assessments, a curative resection was regarded as an en-bloc resection with the lateral margin free of neoplasma, with no lymphatic or vascular invasion, and depth of invasion of ≤500 μm from the muscularis mucosa. A tumor was also considered to be curatively resected when some components of a poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma or signet-ring cell carcinoma were found during the pathological examination. The ESD procedure time was defined as the time interval between endoscope insertion and removal.

Ethics

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the study protocol was approved by the medical ethics committee of our hospital. The risks and benefits of ESD were explained beforehand and written informed consent was obtained from all 44 patients.

Results

All data on patient characteristics and pathological features are summarized in Table 1. Of the 44 patients with early EGJ cancer, only four (9.1 %) were females. The mean age of the cohort was 70.0 years (range, 42–84). Twenty-four (54.5 %) tumors were located on the LC of the EGJ, 11 (25.0 %), on the PW, and nine (20.5 %) on the AW. Twenty-three tumors (52.3 %) were elevated and 10 (22.7 %) of these tumors also had a central depression. Twenty (45.5 %) of the other 21 tumors were depressed, but only one (2.3 %) of these tumors had an elevated mucosa (which was reddish in color and located in the center of the depression). The one (2.3 %) remaining tumor was a protruded lesion. Biopsy specimens in all 44 cases revealed differentiated adenocarcinoma, but only three cases included some components of poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma. There were 30 standard indication cases; the remaining 14 cases were expanded indication cases. All cases were planned for curative treatment. The mean resected specimen and tumor sizes were 35 mm (range, 15–58) and 17 mm (range, 5–47), respectively. The median procedure time was 121 min (range, 49–272), and 13 tumors (29.5 %) were pathologically suspected of having developed from short-segment Barrett’s esophagus. All 44 tumors were primarily differentiated adenocarcinomas, although five tumors (11.4 %) included some components of a poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma in either just the submucosal layer (two tumors, 4.5 %) or just the mucosal layer (three tumors, 6.8 %). Biopsy specimens from two of these five tumors indicated differentiated adenocarcinomas prior to ESD, but pathological examinations of the two tumors revealed some poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma components in just the submucosal layer of each tumor. There were no complications such as bleeding or perforation and all cases were successfully resected en bloc, with a curative resection rate of 84.1 % (37/44). The curative resection rates of the standard and expanded indication cases were 90.0 % (27/30) and 71.4 % (10/14), respectively. There were no instances of stenosis in any case after ESD. No recurrent or distant metastatic carcinomas were detected during a mean follow-up period of 33 months (range, 6–64) and only two patients, both of whom had undergone curative resections for intramucosal tumors, died (from other cancer-related causes).

The details of the seven non-curative cases are summarized in Table 2. One non-curative resection case was pathologically revealed to be oral lateral margin-positive (case 1, Fig. 2a–d), but the patient declined surgery. Another non-curative resection case (case 2) involved both slight submucosal invasion <500 μm (SM1) and venous invasion, but this patient also declined subsequent gastrectomy. The tumor in this case, in fact, included some components of a poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma located in just the submucosal layer. The remaining five non-curative resection cases all had deep submucosal invasion ≥500 μm (SM2) (cases 3–7) with two of these cases also involving lymphatic invasion (cases 3 and 4) and one of them being vertical margin-positive as well (case 3). The other SM2 case with lymphatic invasion involved some components of a poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma located in just the submucosal layer (case 4, Fig. 3a–d). Another SM2 case was also oral lateral margin-positive (case 5), while the remaining two SM2 cases involved only submucosal deep invasion (cases 6 and 7). All five SM2 non-curative resection patients underwent laparoscopic gastrectomy, with no residual tumors or lymph node metastases revealed pathologically. In conclusion, there were no significant differences in tumor location, tumor morphology, tumor size, histology of biopsy specimens, or standard versus expanded indication cases with regard to risk factors for curative and non-curative resection. However, submucosal invasion, positive tumor margins, lymphovascular invasion, and some components of poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas in just the submucosal layer were significantly more common in non-curative resection cases (Table 3).

Non-curative resection case 1 involved the development of adenocarcinoma below the squamous epithelium. a Conventional endoscopy revealed reddish depressed mucosa at the EGJ. b Chromoendoscopic view of tumor with indigo-carmine dye. c Histological mapping of the resected specimens, with red lines indicating cancerous tumor. AW anal wedge, OW oral wedge. d Pathological examination revealed adenocarcinoma that had developed approximately 330 μm below the squamous epithelium. H&E, ×40

Non-curative resection case 4 included some poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma components located in just the submucosal layer. a Conventional endoscopy revealed reddish depressed mucosa at the EGJ. b Chromoendoscopic view of tumor with indigo-carmine dye. c Histological mapping of the resected specimens, with red lines indicating the cancerous tumor and the shaded portion indicating the submucosal invasion lesion. AW anal wedge, OW oral wedge. d Pathological examination revealed mixed primarily differentiated adenocarcinoma with some poorly differentiated components located in just the submucosal layer. H&E, ×100

Discussion

An increasing number of EGJ cancers have recently been diagnosed in Western countries. For many years, total gastrectomy with a transhiatal resection of the distal esophagus was regarded as the gold standard treatment for all EGJ cancer patients [12]. Such surgery entails the risk of overtreatment and reduces postoperative patient quality of life, however, so the necessity for performing such an extensive resection has been questioned in patients with early EGJ cancers.

In contrast, remarkable progress has recently been made in Japan in the development of various methods of endoscopic resection [13–15]. In particular, the introduction of ESD has made possible the en-bloc resection of larger tumors, as well as tumors in difficult locations such as the EGJ [16, 17]. The en-bloc resection rate has risen to nearly 90 % with the maturation of this procedure in major Japanese medical facilities regularly performing ESDs [18]. Consequently, we believe that ESD is an indispensable treatment method because it is possible to pathologically evaluate the risks of recurrence and metastasis more accurately. ESD does, however, have several limitations, including being a time-consuming procedure with a relatively high complication rate owing to bleeding and perforations. The risk of complications is even higher in more difficult cases such as those involving EGJ tumors, although our ESD technique using the IT knife 2 with the retroflex view is not usually affected by respiratory movement. Injecting hyaluronic acid into the submucosal layer also usually lifts the mucosa enough so that the muscularis propria and the vessels running through it can be identified more easily and the submucosal layer can be dissected without cutting any of these vessels. As a result, ESD has been demonstrated to be a safe and effective treatment method despite a somewhat higher risk of complications, such as bleeding and perforation, particularly in more technically difficult locations.

We compared risk factors between curative and non-curative resection cases. Before the ESDs, there were no significant differences in any risk factors, including tumor location, tumor morphology, tumor size, histology of biopsy specimens, or standard versus expanded indications. However, the tumors were larger, the histology of biopsy specimens included some components of poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas, and expanded indication cases were more common in the non-curative cases. We believe the reason there were no statistically significant differences in these risk factors was that we did not have a large number of patients with EGJ cancer who underwent ESDs in our hospital. After the ESDs, significant differences between the curative and non-curative cases were shown in tumor depth, tumor margin, lymphovascular invasion, and some components of poorly differentiated adenocarcinomas in just the submucosal layer. Although it is possible to accurately predict some components of differentiated and undifferentiated adenocarcinomas in the mucosal layer using ME-NBI [19, 20], it is impossible to use this method to diagnose the existence of adenocarcinomas in just the submucosal layer, because ME-NBI microvascular pattern findings apply only to the superficial mucosal layer [21]. Transhiatal esophagectomy for adenocarcinoma of the distal esophagus and cardia may be more invasive treatment in node-negative cancer. We should therefore plan to perform ESDs first to evaluate the pathology of the tumor to avoid unnecessary treatment if we do not suspect deep submucosal invasion of the tumor.

In conclusion, ESD was shown to be a safe, effective, and minimally invasive treatment for early EGJ cancer. For tumors without any submucosal invasion findings, therefore, ESD is an acceptable treatment option, in addition to also being suitable for diagnostic purposes in evaluating the need for surgery.

References

Blot WJ, Devesa SS, Kneller RW, Fraumeni JF Jr. Rising incidence of adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and gastric cardia. JAMA. 1991;265:1287–9.

Blot WJ, Devesa SS, Fraumeni JF Jr. Continuing climb in rates of esophageal adenocarcinoma: an update. JAMA. 1993;270:1320.

Pera M, Cameron AJ, Trastek VF, Carpenter HA, Zinsmeister AR. Increasing incidence of adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and esophagogastric junction. Gastroenterology. 1993;104:510–3.

Ekstrom AM, Signorello LB, Hansson LE, Bergstrom R, Lindgren A, Nyren O. Evaluating gastric cancer misclassification: a potential explanation for the rise in cardia cancer incidence. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:786–90.

Kusano C, Gotoda T, Khor CJ, Katai H, Kato H, Taniguchi H, Shimoda T. Changing trends in the proportion of adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction in a large tertiary referral center in Japan. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:1662–5.

Kakushima N, Yahagi N, Fujishiro M, Kodashima S, Nakamura M, Omata M. Efficacy and safety of endoscopic submucosal dissection for tumors of the esophagogastric junction. Endoscopy. 2006;38:170–4.

Yoshinaga S, Gotoda T, Kusano C, Oda I, Nakamura K, Takayanagi R. Clinical impact of endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial adenocarcinoma located at the esophagogastric junction. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:202–9.

Ikeda K, Isomoto H, Oda H, Shikuwa S, Mizuta Y, Iwasaki K, Kohno S. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of a minute intramucosal adenocarcinoma in Barrett’s esophagus. Dig Endosc. 2009;21:34–6.

Siewert JR, Stein HJ. Classification of adenocarcinoma of the oesophagogastric junction. Br J Surg. 1998;85:1457–9.

Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Guidelines for gastric cancer treatment. Tokyo: Kanehara-shuppan; 2004.

The Paris endoscopic classification of superficial neoplastic lesions: esophagus, stomach, and colon: November 30 to December 1, 2002. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:S3–43.

Rudiger Siewert J, Feith M, Werner M, Stein HJ. Adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction: results of surgical therapy based on anatomical/topographic classification in 1,002 consecutive patients. Ann Surg. 2000;232:353–61.

Ono H, Kondo H, Gotoda T, Shirao K, Yamaguchi H, Saito D, Hosokawa K, Shimoda T, Yoshida S. Endoscopic mucosal resection for treatment of early gastric cancer. Gut. 2001;48:225–9.

Oyama T, Tomori A, Hotta K, Morita S, Kominato K, Tanaka M, Miyata Y. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of early esophageal cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:S67–70.

Fujishiro M, Yahagi N, Kakushima N, Kodashima S, Ichinose M, Omata M. Successful endoscopic en bloc resection of a large laterally spreading tumor in the rectosigmoid junction by endoscopic submucosal dissection. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:178–83.

Miyamoto S, Muto M, Hamamoto Y, Boku N, Ohtsu A, Baba S, Yoshida M, Ohkuwa M, Hosokawa K, Tajiri H, Yoshida S. A new technique for endoscopic mucosal resection with an insulated-tip electrosurgical knife improves the completeness of resection of intramucosal gastric neoplasms. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:576–81.

Yamamoto H, Kawata H, Sunada K, Satoh K, Kaneko Y, Ido K, Sugano K. Success rate of curative endoscopic mucosal resection with circumferential mucosal incision assisted by submucosal injection of sodium hyaluronate. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:507–12.

Oda I, Saito D, Tada M, Iishi H, Tanabe S, Oyama T, Doi T, Otani Y, Fujisaki J, Ajioka Y, Hamada T, Inoue H, Gotoda T, Yoshida S. A multicenter retrospective study of endoscopic resection for early gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2006;9:262–70.

Yao K, Oishi T, Matsui T, Yao T, Iwashita A. Novel magnified endoscopic findings of microvascular architecture in intramucosal gastric cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:279–84.

Kaise M, Kato M, Urashima M, Arai Y, Kaneyama H, Kanzazawa Y, Yonezawa J, Yoshida Y, Yoshimura N, Yamasaki T, Goda K, Imazu H, Arakawa H, Mochizuki K, Tajiri H. Magnifying endoscopy combined with narrow-band imaging for differential diagnosis of superficial depressed gastric lesions. Endoscopy. 2009;41:310–5.

Nakayoshi T, Tajiri H, Matsuda K, Kaise M, Ikegami M, Sasaki H. Magnifying endoscopy combined with narrow band imaging system for early gastric cancer: correlation of vascular pattern with histopathology (including video). Endoscopy. 2004;36:1080–4.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Omae, M., Fujisaki, J., Horiuchi, Y. et al. Safety, efficacy, and long-term outcomes for endoscopic submucosal dissection of early esophagogastric junction cancer. Gastric Cancer 16, 147–154 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-012-0162-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-012-0162-5