Abstract

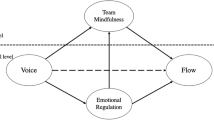

Team communication is considered a key factor for team performance. Importantly, voicing concerns and suggestions regarding work-related topics—also termed speaking up—represents an essential part of team communication. Particularly in action teams in high-reliability organizations such as healthcare, military, or aviation, voice is crucial for error prevention. Although research on voice has become more important recently, there are inconsistencies in the literature. This includes methodological issues, such as how voice should be measured in different team contexts, and conceptual issues, such as uncertainty regarding the role of the voice recipient. We tried to address these issues of voice research in action teams in the current literature review. We identified 26 quantitative empirical studies that measured voice as a distinct construct. Results showed that only two-thirds of the articles provided a definition for voice. Voice was assessed via behavioral observation or via self-report. Behavioral observation includes two main approaches (i.e., event-focused and language-focused) that are methodologically consistent. In contrast, studies using self-reports showed significant methodological inconsistencies regarding measurement instruments (i.e., self-constructed single items versus validated scales). The contents of instruments that assessed voice via self-report varied considerably. The recipient of voice was poorly operationalized (i.e., discrepancy between definitions and measurements). In sum, our findings provide a comprehensive overview of how voice is treated in action teams. There seems to be no common understanding of what constitutes voice in action teams, which is associated with several conceptual as well as methodological issues. This suggests that a stronger consensus is needed to improve validity and comparability of research findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Consider a junior employee at a marketing team meeting and a nurse working on an emergency response team who voice their concerns regarding incorrect procedures. Both speak up about work-related topics (Morrison 2014) with the intention of preventing negative consequences for the respective organization (Ashford et al. 2009). However, the consequences in the two work environments differ vastly. In case of the nurse, speaking up about errors and mistakes can help to identify hazards and prevent patient harm, in extreme cases death (Lin and Johnson 2015; Noort et al. 2019). Teams in settings such as this are commonly referred to as action teams that work in high-reliability organizations (e.g., in the high-hazard healthcare, military, or aviation domains; Sundstrom et al. 2000). Here, voice is vital to prevent mistakes that potentially threaten human life and well-being. In contrast, mistakes in other team settings, such as the marketing team in our example, might also lead to adverse outcomes, such as losing customers or damaging the organizations’ reputation, but errors in those settings usually have less severe consequences.

These situations—a junior employee and a nurse stating their concerns—are typical examples for the expression of “voice” at the workplace. In general, voice has been defined as “informal and discretionary communication by an employee of ideas, suggestions, concerns, information about problems, or opinions about work-related issues to persons who might be able to take appropriate action, with the intent to bring about improvement or change” (Morrison 2014, p. 174). From early on, voice research has emphasized the importance of voice in the team context (Van Dyne and LePine 1998). In this context, research has linked voice to improved team learning and better identification of problems and hazardous situations (Morrison and Milliken 2000; Burris 2012; Liang and Farh 2018). As a result, voice is nowadays regarded as an essential part of team communication that is beneficial for organizations (Howell et al. 2015). Particularly, in action teams that work in high-reliability environments, voice is important to maintain safety and team performance (Edmondson 2003; Kolbe et al. 2012). For example, if nurses observe that a surgeon is about to make a mistake such as incising the wrong leg (Kohn et al. 2000), it would be crucial that they express their concerns and thus prevent wrong procedures and patient harm.

Despite the clear importance of voice in action teams, the literature on this topic is rather heterogeneous and characterized by a plethora of different conceptual and methodological approaches to assess voice (Noort et al. 2019). Specifically, we see three potential inconsistencies in the voice literature: (1) the definition of voice, (2) the measurement of voice, and (3) the role of the voice recipient. First, “voice” is usually used interchangeably for “upward voice” or “speaking up”. Moreover, terms like “employee voice”, “upward communication”, or “upward feedback” (Bashshur and Oc 2015; Liang et al. 2012; Milliken et al. 2003) refer to the same or at least to very similar phenomenon as voice.Footnote 1 This is potentially problematic, as researchers seem to use not only different terms, but also different definitions (Morrison 2011).

Second, this apparent heterogeneity with regard to the definition of voice can lead to methodological issues when it comes to investigating voice empirically. Moreover, if the conceptual and methodological treatment of voice systematically differs across studies, aggregation of findings regarding voice in practice would be questionable, as measured constructs are difficult to compare (Burt 1976; Howell et al. 2007). This in turn might hinder the taking of appropriate steps, for instance the development of interventions that can improve effective communication (i.e., including voice) in action teams.

Third, another apparent neglect of voice research concerns the recipient. Simply voicing a concern does not always seem to be enough (Burris et al. 2013; Krenz et al. 2019). To stay with the example of leg surgery, expressing concerns about the surgeon’s procedure does not necessarily prevent patient harm. To actually prevent a serious mistake, the surgeon must react adequately (Morrison 2014). Therefore, highlighting the recipient of voice is important, because the recipient is co-responsible for the voice message’s outcome.

Taken together, we submit that the conceptual and methodological issues of empirical voice research make it difficult to compare and integrate findings across different fields, such as human resource management, industrial relations, and organizational behavior (Wilkinson et al. 2019). This is particularly problematic in action teams, where voice can help to avoid disastrous outcomes including plane crashes or patient deaths (Ashford et al. 2009).

Thus, following the call for bridging the gap between theory and practice (Salas et al. 2018), we aim to review the conceptual (i.e., definitions and role of the recipient) and methodological (i.e., type of measurements and instruments that were used) approaches in previous research on voice in action teams. Specifically, in the present review, we aim to provide an overview of how voice has been treated conceptually and methodologically in studies in the action team literature. We focus on the following questions: (a) How was voice defined? (b) How was voice assessed? and (c) How was the recipient operationalized (i.e., definitions and measurements)?

The goal of the current review of the literature is to provide an overview of how voice has been treated in empirical research, and in doing so, to illustrate potential methodological and conceptual inconsistencies. By identifying these gaps, we aim to contribute to the improvement of future research on voice in action teams as well as to the improvement of future training and interventions based on this research.

1.1 Theoretical background

1.1.1 Action team work

Action teams are characterized as teams that are typically composed of members with highly specialized skills (Sundstrom et al. 2000) that perform demanding tasks under high time pressure (Klein et al. 2006). In general, action team work is difficult to predict: situations like heart attacks or fires are time sensitive and cannot be scheduled or determined by the clock (i.e., epochality of the action team’s work; Ishak and Ballard 2012). Furthermore, team members’ actions are usually irreversible: Wrong treatments of patients are hard to reverse (i.e., finality of the work; Ishak and Ballard 2012). Although the high-reliability settings in which action teams operate involve the management of complex technologies, non-technical skills—also termed human factors—play a crucial role (Weick et al. 1999). For example, research has highlighted the importance of team processes and emergent states in these settings (Baker et al. 2006; Burtscher et al. 2018a, b; Salas et al. 2018). Similarly, team work failure and communication errors have been shown as one of the most frequent reasons for adverse event in both aviation and healthcare (Lingard et al. 2004; Kanki 2019; O’Connor et al. 2008; Williams et al. 2010).

1.1.2 Action teams and crew resource management

To address this issue, the aviation industry started to develop crew resource management (CRM) trainings focusing on non-technical skills in the 1980s that are now recommended by all large national and international airlines (Flin et al. 2008) and adopted by other action team environments, such as such as merchant navy, offshore oil industry, nuclear power, and medicine (Flin et al. 2002). Besides leadership, decision making, and situational awareness, communication has been identified as a core non-technical skill (European Union Aviation Safety Agency 2019; U.S. Department of the Air Force 2019). One important function of communication in CRM trainings represents the sending and receiving of information (Kanki 2019). Moreover, CRM training teaches action team members to communicate in an assertive manner and to be able insisting on one’s position until being convinced that other opinions are better (Salas and Cannon-Bowers 2001; Kanki 2019; Foushee and Helmreich 1993). In other words, communication is seen as an important non-technical skill in action teams (Omura et al. 2017; Morrison 2014).

1.1.3 Voice

Voice is considered as an essential aspect of verbal communication within and between action teams (Edmondson 2003). Morrison (2014) defined employee voice as “informal and discretionary communication by an employee of ideas, suggestions, concerns, information about work-related issues to persons who might be able to take appropriate action, with the intent to bring about improvement or change” (p. 174). Morrison’s definition, which was based on previous empirical research (Detert and Burris 2007; Van Dyne and LePine 1998; Edmondson 2003), strongly influenced the conceptual frameworks of subsequent voice research (Farh and Chen 2018; Guenter et al. 2017; Noort et al. 2019; Weiss et al. 2018). Nevertheless, as mentioned above, the terms used and the definitions of voice vary in the literature. Especially in fields such as human resource management, organizational behavior, and industrial relations, the understanding of voice differs across disciplines (Wilkinson et al. 2019). Despite this, voice as a construct has attracted increasing research attention (Morrison and Milliken 2000; Pinder and Harlos 2001; Van Dyne and LePine 1998). Voice has been described as extra-role communication behavior (Van Dyne et al. 1995; Morrison 2014) and as distinct from related constructs such as issue selling, whistle blowing, or prosocial organizational behavior (Morrison 2011). Voice is considered as an aid to identifying problems, improving organizational effectiveness, facilitating innovation and learning, and discerning hazardous situations (Burris 2012; Liang and Farh 2018; Morrison and Milliken 2000). These organizational key outcomes led to researchers’ growing interest in what drives voice (Ng et al. 2019). As a result, studies have provided important insights into the antecedents of voice on the individual, team, and organizational level (Bashshur and Oc 2015; Knoll et al. 2016; Morrison 2011) that can motivate (e.g., assertiveness, psychological safety, ethical leadership) or inhibit (e.g., powerlessness, climate of fear, hierarchical structure) employee voice (Morrison 2014). In general, voice research has focused on the sender’s perspective: Studies have investigated personal traits (e.g., proactivity; Grant et al. 2011) or other factors that influence the sender’s willingness to express voice (e.g., leader behavior or voice climate within a work group; Chamberlin et al. 2017; Morrison et al. 2011), thereby identifying barriers and enablers of voice. It is only in more recent years that researchers have begun to consider the recipient’s perspective (Burris 2012; Detert and Burris 2007; Fast et al. 2014).

1.1.4 Recipient of voice

One of the most common examples of the importance of voice—or team communication in general—is the tragic airplane crash on the island of Tenerife in 1977, which led to the death of 583 passengers and crew members. Sound recordings from the airplane showed that a flight engineer had expressed his concerns to the captain as to whether the runway was clear for their departure. Unfortunately, the engineer’s voice was not assertive enough to keep the captain from starting the takeoff, which could have prevented the disaster. In the literature, this and similar examples of airplane disasters caused by communication breakdowns are well known (Bienefeld and Grote 2012; Edwards et al. 2009; Flin et al. 2002; Green et al. 2017; Salazar et al. 2014). Surprisingly, despite the clear importance of the role of the captain, who did not respond adequately to the engineer’s voice, this case has never been considered as an indicator of the importance of the recipient of voice. Similarly, the voice literature is somewhat limited due to its neglecting to consider the role of the voice recipient, even though recipients are clearly instrumental in determining the consequences of voice.

Although some studies have pointed out that voice is includes a sender (or “voicer”) and a recipient (or “receiver”; Bashshur and Oc 2015), underlining that voice is a two-sided process, there is a lack of clarity regarding the recipient. Morrison (2014) described the recipient of upward voice as a supervisor or a person in an organizationally higher status position, implying that the recipient is someone who can respond and act adequately. Interestingly, studies differ on the question of who can be the recipient of voice (Gao et al. 2011). Sometimes the recipient is a person on a higher hierarchical level (Nembhard and Edmondson 2006), and sometimes the recipient is a peer of the sender (Noort et al. 2019). Sometimes, the recipient seems to involve both (supervisor and peers), for example a whole team (Li et al. 2017). Additionally, it remains unclear if the recipient is limited to merely one person (Salazar et al. 2014) or if the recipient(s) can be multiple people (Sherf et al. 2018). In other words, conceptualizations of the recipient are inconsistent. Particularly in action teams, this is problematic, as hierarchical structures (i.e., implying a higher status position of the recipient) are suggested to be a significant barrier for team members’ voice (Friedman et al. 2015; Klein et al. 2006; Weiss et al. 2017). For instance, studies have shown that fear of being punished or rejected by someone with a formally higher status (Milliken and Lam 2009; Morrison 2014) is one of the most prevalent barriers to voicing concerns in healthcare (Morrow et al. 2016; Raemer et al. 2016; Weiss et al. 2017). However, if peers could be voice recipients, too, hierarchical barriers would be less relevant. It is therefore important to clearly define the (group of) recipients of voice in action teams. For that reason, we aim to identify the recipient both in terms of the definition of voice as well as in terms of the actual measurement of voice.

1.1.5 Measurement of voice

As one of the pioneers of voice research in action teams, Edmondson (2003) assessed the “ease of speaking up” in operating room teams by means of one single interview question. Edmondson’s approach apparently shaped subsequent research, in that voice has been investigated mostly via self-report (Burris 2012; Edmondson 2003; Nembhard and Edmondson 2006). The self-report measures usually investigate the sender’s or recipient’s perspective on perceived past, actual, or hypothetical voice behavior (Liang et al. 2012; Morrison 2011; Nembhard and Edmondson 2006). For hypothetical voice behavior, studies have used scenarios and vignettes to investigate peoples’ willingness to voice or how people think they would behave (Fast et al. 2014; Sayre et al. 2012). In the present review, we want to explore what instruments (i.e., self-constructed vs. validated scales or items) have been used to assess voice in action teams. Our aim is to investigate the comparability of instruments that have been used, including analysis of their contents.

Addressing the lack of investigating “real behavior”, a growing body of research has investigated team communication—especially in action team context—via behavioral observation (Edmondson 2003; Pattni et al. 2019; Waller and Kaplan 2018). For example, in healthcare, coding schemes such as Co-ACT (Kolbe et al. 2013), ANTS (Flin et al. 2010), and OTAS (Healey et al. 2004) have been developed for observing and assessing team communication behavior. Particularly in action teams, team training (e.g., CRM training) is conducted based on simulated emergency scenarios (Kanki 2019; O’Connor et al. 2008). With the help of these scenarios, team skills (i.e., technical skills and soft skills) can be further developed, including team communication (Schick et al. 2015). According to Marks et al.’s (2000) theoretical framework, team communication can be divided into two parts: communication quality and communication frequency. In the present review, we aim to explore what instruments have been used to assess voice in action teams during behavioral observation. Addressing this question, we use Marks et al. (2000) approach to distinguish between assessment of voice quality and voice frequency.

1.1.6 The present review

Taken together, voice represents a significant aspect of communication in action teams. Not only the sender, but also the recipient of voice is important, as the recipient needs to react adequately to the voice message. In the present literature review, we describe how voice has been treated conceptually as well as methodologically, thereby providing a critical perspective of previous voice research in action teams. This can aid identification of potential gaps in the common understanding of voice in action teams that could be considered in future research. Furthermore, this review provides a comprehensive overview of measurement instruments that have been used to investigate voice in action teams. This overview can facilitate the planning of new studies and support researchers and practitioners in their choice of suitable instruments. Moreover, we aim to convey a perspective that emphasizes voice as a dynamic process, considering the sender as well as the recipient. Future training and interventions might benefit from integrating both senders and recipients of voice.

2 Method

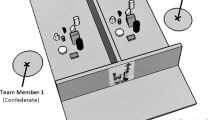

We included empirical works published up to May 2019 in our literature review. As our search strategy, we conducted a three-step procedure (Booth et al. 2016) to extract relevant empirical articles that investigated voice and action teams. Figure 1 summarizes the stepwise outcomes of the literature search.

First, to identify relevant empirical studies, we searched the literature using the databases Web of Science Core Collection, SCOPUS, and EBSCOhost (i.e., Medline, PsychIndex, and CINAHL). We combined search terms for voice (i.e., upward voice, lateral voice, speak(ing) up or speak(ing) out, upward communication, upward feedback, employee silence, or organizational silence) with terms for team composition (i.e., team, unit, crew, or department) and terms for action teams that work in high-reliability contexts (i.e., action, medical, emergency, surgical, rescue, fire, military, cockpit, air, or oil). This initial step yielded 1395 articles. In a second step, abstracts and titles were screened by the first author of this review. Each article that did not match the extent of this review was excluded. Concretely, we included empirical, peer-reviewed works that investigated voice (i.e., voice as a distinct measure) quantitatively in an action team context (i.e., professional teams only, no student samples). We excluded the article types meta-analysis, review articles or systematic reviews, conceptual/theoretical articles, qualitative articles, commentary without original results, book chapters without original results, and articles that were written in a language foreign to us (i.e., not English). In cases of ambiguity (e.g., title and abstract did not indicate if voice was examined in the context of an action team), articles were initially included. This second step resulted in 159 articles. In a third step, both authors of this review read titles, abstracts, and full texts carefully to identify relevant articles. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion. We also personally contacted voice researchers and performed a reference check of the existing reviews on voice to identify additional papers. A total of 26 articles met the inclusion criteria, including five articles identified through hand-searching.

3 Results

The literature research resulted in 26 studiesFootnote 2 published from 2006 to 2019. The studies were conducted in action teams in different domains: aviation (2 studies), healthcare (22), and military (2). The sample included 13 survey studies, 12 simulation studies, and one field study. Sample sizes ranged from 13 (Beament and Mercer 2016) to 1751 (Bienefeld and Grote 2012) participants. Of the 26 studies, 23 studies treated voice as an outcome variable, and three studies treated voice as a predictor, mediator, or moderator variable (Kolbe et al. 2012; Martínez-Córcoles et al. 2018; McClean et al. 2018). Table 1 summarizes characteristics of the studies reviewed. In the following, we use the term ‘voice’ as a collective term for all variables measured (e.g., past speaking up behavior, speaking up, challenging authority; for an overview see Table 1).

3.1 Voice definitions

Sixteen of 26 articles (62%) provided a definition of voice (i.e., see Table 1), whereas 10 articles (38%) did not explicitly clarify their main variable. For example, in the healthcare domain, voice was defined as “stating concerns (e.g., filing a report, sharing concerns with a supervisor or speaking directly with the individual(s) involved) rather than saying nothing” (Martinez et al. 2015, p. 1). In contrast, one study that was set in the aviation domain provided the following definition: “Speaking up in high-risk contexts is defined as an upward voice directed from lower to higher status individuals within and across teams, that challenges the status quo, to avert or mitigate errors” (Bienefeld and Grote 2012, p. 1). Appendix I provides an overview of all voice definitions.

Definitions included aspects such as sender, recipient, how voice should be made, context, content, and intention of voice. Of these aspects, only voice content was commonly mentioned in every definition. The proposed content of voice messages ranged from very precise (“individual’s willingness to inform attendings when they are struggling or stressed or when they have made an error”; O’Connor et al. 2013, p. 426) to less precise (such as the voice content proposed by Morrison (2011) describing “suggestions, ideas, opinions or concerns”; Weiss et al. 2018, p. 390). Notably, voice content was often associated with a critical nature that challenges actions and opinions of persons in higher status positions (Weiss et al. 2018) or, more generally, challenges the status quo (Bienefeld and Grote 2012).

3.2 Measurements

In our review, we distinguished between two types of measurement: self-report measures (n = 13) and behavioral observation (n = 13). Self-report was based mainly on self-assessments, whereas behavioral observation referred to an external evaluation (i.e., no self-assessment).

3.2.1 Self-report

Overall, self-report studies assessed 18 voice variables by means of 25 instruments (for an overview, see Table 2). Instruments that were used to investigate voice in action teams varied from validated scales and items (n = 11) to self-constructed scales and items (n = 7). Some scales were slightly adapted or modified versions of already validated scales (n = 3), whereas other scales represented a mixture of self-constructed items and validated items from already existing scales (n = 4). Three of 25 measurement instruments contained one single item to assess voice. The number of items on the instruments ranged from 1 to 27 (M = 7.27; SD= 7.34).

By analyzing the instruments used in self-report studies, we identified five key topics: past voice behavior (n = 4), attitudes toward voice (n = 5), current voice behavior (n = 4), voice climate (n = 7), and likelihood/willingness to voice (n = 5). In contrast to the other key topics, investigation of the likelihood/willingness to voice was always related to a vignette that illustrated typical situations (i.e., for the respective action team context) in which the expression of voice would have been necessary (Bienefeld and Grote 2014; Martinez et al. 2017; Schwappach and Gehring 2014). Table 3 shows example items for the five key topics.

3.2.2 Behavioral observation

Each of the 13 behavioral observation studies focused on a single voice variable that was assessed by a specific measurement instrument. Moreover, the instruments that were used to assess voice were mainly modified versions of already existing scales (n = 9). One study used a validated instrument (Kolbe et al. 2012), two studies used self-constructed instruments (Pian-Smith et al. 2009; Raemer et al. 2016), and one study did not report the instrument (Farh and Chen 2018). For a detailed description of studies that investigated voice by means of behavioral observation, see Table 4.

Measures in studies that examined voice via behavioral observation were divided into two main categories: event-focused (n = 7) and language-focused (n = 6). Event-focused voice refers to the identification of voice itself (i.e., whether or when did voice occur), whereas language-focused refers to studies in which the formulation of voice is analyzed in more detail (i.e., rating of the assertiveness of voice). Except for two studies (Raemer et al. 2016; Robb et al. 2015), the theoretical approach to event-focused voice was mainly based on Morrison (2011, 2014) and involved identifying suggestion-, problem-, doubt-, or opinion-focused expressions of voice (Farh and Chen 2018; Weiss et al. 2014) through behavioral observation. For example, Kolbe et al. (2012) coded speaking up by expressions such as “Are you sure you want to intubate right now?” (p. 3). Event-focused coding was mainly used to predict voice frequency as an outcome (n = 6). In only one case was event-focused coding used to also predict voice quality (Robb et al. 2015). Studies using a language-focused approach were all based on Pian-Smith et al.’s (2009) scoring system. This system initially considered challenges towards the: (a) attending surgeon, (b) nurse, or (c) anesthesiologist. Pian-Smith et al. distinguished between five levels of assertiveness, ranging from saying nothing to verbalization of advocacy and inquiry statements (e.g., “I’m wondering about risks of doing this when there’s a low platelet count. How do you decide how to proceed?”; p. 87). This scoring system was usually slightly modified in more recent studies (Friedman et al. 2015; Pattni et al. 2017). In contrast to event-focused voice, language-focused coding was used to predict voice quality as an outcome (n = 3) or a combination of voice quality and frequency (n = 2). In only one case was language-focused voice used to assess voice frequency (Oner et al. 2018).

3.3 Recipient of voice

In the present review, we distinguished three categories of recipients. The first category comprises recipients who clearly have a higher status (HS) in terms of being in higher positions in the organization. For example, “Junior team members should not question the decision made by senior personnel” (Kobayashi et al. 2006, p. 279). The second category considers a recipient in the sender’s “group” (G) who can be either a peer or a higher-status person, or also just the whole group (i.e., more detailed description of the recipient is lacking). For example, “In my clinical area, it is difficult to speak up if I have a patient safety concern” (Martinez et al. 2015, p. 5)”. The third category was used when the recipient was not mentioned and/or not identifiable (i.e., no specific recipient, or NSR). For example, “Over the last 4 weeks, how often did you address an error which—if uncaptured—could be harmful for patients?” (Schwappach and Richard 2018, Appendix). The three categories were not mutually exclusive, as particularly self-report studies employed scales in which the recipient varied between items. Table 5 shows the operationalization of the voice recipient in the studies. Operationalization of the recipient refers to holding definitions against actual measurements. As three studies (Martinez et al. 2015, 2017; Schwappach and Richard 2018) employed more than one instrument to assess voice, we identified 30 instruments in total (i.e., instead of 26). That is why in four cases, definitions were used twice (i.e., so as to be able to compare the additional instruments).

3.3.1 Operationalization of the voice recipient

In 20 available definitions of voice, the recipient was explicitly mentioned as a higher-status person (n = 4), as someone in the group (n = 2), as higher status and not specified (n = 2), or not specified at all (n = 12). Compared to voice definitions, actual measurements of voice involved even more different combinations of voice recipients: higher status (n = 11), higher status and group (n = 6), higher status, group, and recipient not specified (n = 3), higher status and recipient not specified (n = 2), group (n = 5), and group and recipient not specified (n = 3). Finally, in only two of 30 measurements (7%), the recipient was both explicitly mentioned in the definition of voice and operationalized accordingly. Considering studies that did not provide a definition of voice but used terms for their measured variables such as “challenging authority” and “speaking up” that indicated hierarchical relationships between sender and recipient, there would be five additional cases in which the recipient was adequately operationalized (see Table 5).

4 Discussion

We reviewed original quantitative studies that investigated voice in action teams. In sum, our review of the literature yielded 26 separate studies, which were predominantly conducted in healthcare teams. Our findings show that only 16 out of 26 articles contained an explicit voice definition. An equal number of studies (i.e., 13 each) investigated voice by means of self-report and by behavioral observation. Whereas behavioral observation instruments were consistently based on either of two theoretical approaches, self-report instruments were more heterogeneous. Another issue concerns the voice recipients; recipients were not consistently defined or measured, which resulted in poor operationalization of the voice recipient. This is the first time that the treatment of voice in action teams has been systematically analyzed in terms of conceptual as well as methodological approaches. Our findings indicate several challenges and implications for voice research in action teams, which we discuss in the following sections.

4.1 Definition of voice

More than one-third of the articles reviewed do not provide a definition of voice. This is problematic, as in general variables that are investigated in research articles should be clarified and distinguished from similar constructs in advance (Suddaby 2010). A possible explanation for not defining the term voice could be that at a first glance, “upward voice”, “speaking up”, or “challenging authority” might appear to be self-explanatory and therefore not worth describing in more detail. However, different researchers’ approaches of that are in line with varying definitions and interpretations of voice (Wilkinson et al. 2019) demonstrate that voice as a concept is not self-explanatory. There is a great need for definitions to adequately operationalize the construct of voice and thus obtain valid and comparable measurements (Moosbrugger and Kelava 2012).

In addition, the aspects mentioned in definitions of voice vary considerably. For example, studies mention sender, recipient, how voice should be made, context, and intention of voice in different combinations and use them very inconsistently. Nevertheless, voice content represents the only common aspect of every definition. Although voice content is always mentioned, there is much room for interpretation, in particular when definitions were borrowed from Morrison (2014) (e.g., “suggestions, concerns, or information about a team’s task”; Farh and Chen 2018, p. 97). This “umbrella construct” of voice (Morrison 2011) is problematic, as more nuanced forms of voice content that specify the type of information conveyed would be valuable (Morrison 2011). Notably, one study—McClean et al. (2018)—examined the effects of different types of voice, such as promotive and prohibitive voice. Whereas promotive voice is associated to the expression of suggestions or new ideas, prohibitive voice is associated to the expression of concerns about incidents that can be harmful to the organization (Liang et al. 2012). Although the distinction between promotive and prohibitive voice has become established in the voice literature (see the meta-analysis in Chamberlin et al. 2017), this distinction is mostly absent in action team research. In action teams, however, we see a potential benefit of explicitly distinguishing voicing a concern from voicing an idea, as the former is more likely to prevent harm and might be more urgent (Lin and Johnson 2015).

4.2 Measurements of voice

Types of voice measurements (i.e., self-report measures and behavioral observation) were equally distributed in the studies in our literature review. The investigation of voice by means of self-report appears to be highly inconsistent, as the instruments varied from self-constructed items to validated scales.

In sum, nearly the half of the self-report studies used self-constructed instruments or even single items to investigate voice (Bienefeld and Grote 2012; Martinez et al. 2017). Although these self-constructed voice instruments are usually developed by experts in the respective field (Belyanski et al. 2011), comparability of different voice measurements is lacking, which leads to fragmentation of research findings.

In addition to the high inconsistency of self-report instruments, the contents of the instruments included different key topics, such as past voice behavior, attitudes toward voice, current voice behavior, voice climate, and likelihood/willingness of voice. These key topics make it difficult to integrate the contents of voice instruments across studies. This is problematic, as content differences between instruments lead to the conclusion that single instruments are possibly not relevant and representative enough to measure the same target construct (i.e., voice), suggesting a lack of content validity (Haynes et al. 1995).

Besides the inconsistency of self-report measures regarding construction and content, the use of post hoc measures as reliable data may be problematic when examining team dynamics (Kolbe and Boos 2019; Kozlowski 2015; Noort et al. 2019). For example, self-report data can be influenced by individuals’ espoused theories (theories involving their values, attitudes, and beliefs; Argyris and Schon 1974). These espoused theories do not necessarily represent actual theories-in-use (effectively applied theories; Argyris and Schon 1974). This discrepancy between how people think they would behave and how they actually behave is particularly noticeable when it comes to potentially threatening and embarrassing issues, which are prevalent in many voice situations (Argyris 1980). Thus, if research relied solely on self-report data, there would be still a lack of insight regarding when, whether, and how people show voice (Krenz et al. 2020).

Our findings show that the studies that investigate voice by means of behavioral observation can be divided into two categories: event-focused and language-focused. In most studies, event-focused voice referred to voice frequency as an outcome (Weiss et al. 2014), whereas language-focused voice was related to the assessment of voice quality (i.e., assertiveness; Pian-Smith et al. 2009). Moreover, 12 of 13 studies were conducted in simulated settings, usually representing parts of training or an intervention for professional healthcare teams (Raemer et al. 2016; Weiss et al. 2018). As a notable exception, Farh and Chen (2018) observed the voice behavior of medical teams conducting routine surgeries in the field. Although simulations are created as realistically as possible, team members’ behavior may differ from their behavior during real emergency situations, as they perceive training as psychologically safer than their work with real patients (Edmondson and Lei 2014). Thus, simulations could ease the barrier of speaking up (Weiss et al. 2018). Nevertheless, compared with self-report, the investigation of voice in action teams by means of behavioral observation (i.e., in simulated training courses or field settings) seems to be advantageous, as they capture real-time behaviors (e.g., voice) that can help to identify and understand influences of team phenomena (Waller and Kaplan 2018).

Another aspect is the differentiation between communication (i.e., voice) frequency and quality (Marks et al. 2000). More specifically, in the present review, voice frequency as an outcome is associated with the aggregation of voice occurrences (Kolbe et al. 2012; Raemer et al. 2016; Weiss et al. 2018), whereas voice quality is associated with the assertiveness of the respective voice (Friedman et al. 2015; Pattni et al. 2017; Sydor et al. 2013). Frequency measures demonstrate the actual occurrence of voice, which is, notably, not taken for granted in the context of high-reliability environments (Detert and Edmondson 2011; Barshi and Bienefeld 2018). However, these frequency measures provide less information about the explicit formulation of the voice message, whereas quality measures evaluate how assertively the sender has expressed his or her voice message. By investigating the assertiveness of voice, assertiveness implicitly refers to a counterpart (e.g., an attending anaesthesiologist; Pian-Smith et al. 2009). With that, assertiveness measures of voice address one important factor: the likelihood of being heard by the recipient.

4.3 Recipient of voice

Apart from a few exceptions, our findings indicate that the recipient of voice was not clearly defined in either definitions or measures. More specifically, most studies did not explicitly clarify who the potential recipient can be (i.e., higher status vs. peer) or if the recipient is a single person or a group (i.e., dyadic communication vs. team communication).

Previous research considers voice as challenging the status quo (Tangirala and Ramanujam 2012; Wilkinson et al. 2019), which refers to situations in which those who bear responsibility might feel offended (Detert and Burris 2007). In action teams, hierarchical differences are strongly emphasized through authority gradients, such as for example between nurses and physicians in healthcare (Weiss et al. 2017) or between first officers and captains in aviation (Bienefeld and Grote 2014). These authority gradients in action teams are considered to be significant barriers for the expression of voice (Friedman et al. 2015; Klein et al. 2006). Taken together, the concept of voice in action teams might be difficult to delineate from a hierarchical relationship between sender and recipient. Nevertheless, our results showed that more than half of the studies reviewed do not distinguish between peers or higher-status persons as potential voice recipients (Islam et al. 2019; McClean et al. 2018). This is problematic, as research findings that refer to different recipients are difficult to compare. Voicing concerns toward a peer might be easier because hierarchical barriers disappear. This could lead to a higher level of psychological safety of the sender that in turn facilitates the expression of voice (Edmondson 2003).

Another aspect regarding the recipient of voice concerns clarification of the number of persons being addressed, ranging from one single person (Martínez-Córcoles et al. 2018) to the whole group (Islam et al. 2019). The number of recipients might affect not only the sender (Morrison 2011) but also the recipient of voice. From a sender’s perspective, multiple recipients (i.e., a whole group) could increase the barrier against speaking up, particularly if the group is composed of only higher-status persons who are associated with dominance (Islam and Zyphur 2005). On the other hand, if the group is widely composed of peers, perceived peer support might facilitate the expression of voice (Morrow et al. 2016). Moreover, from the recipients’ perspective, voice as “talking to the room”—that is, no explicit recipient is addressed but the room at large (Burtscher et al. 2018a, b)—could lead to a diffusion of responsibility (Kolbe et al. 2014), which in turn could lead to delayed responses. Taken together, the number of recipients might affect the sender’s voice on several levels.

Neither self-report studies nor behavioral observation studies considered the reaction of the voice recipient as a distinct construct. As a notable exception, Schwappach and Richard (2018) mentioned the reaction of the recipient in two items of their scale “Psychological safety for speaking up”, and Kolbe et al. (2012) observed the reaction of the recipient in terms of changes in coordination behavior. However, the recipient’s reaction is important, because for one, the recipient contributes to the outcome of voice (Burris et al. 2017) and for another, the recipient’s reactions could affect the likelihood of subsequent voice (King et al. 2019). Although the recipient’s reaction has been investigated with regard to the sender’s evaluation as an outcome (Burris et al. 2013; Crant et al. 2010; Whiting et al. 2012), there are still hardly any studies available on immediate outcomes of the recipient’s reaction, such as the implementation or rejection of voice. This might be particularly important in the action team context, as the implementation or rejection of voice is likely to have significant consequences, ranging to decisions concerning life-threatening crises (Sydor et al. 2013). Moreover, the recipient’s reaction will probably affect subsequent voice, whether voiced suggestions were endorsed or not (King et al. 2019). In particular, adequate responses in terms of interpersonal fairness, including respectful treatment of the sender (Tangirala and Ramanujam 2009), could more likely lead to subsequent voice. In sum, although adequate responses to voice seems to be crucial for the whole communication process, there is there are barely any studies examining the recipient’s reaction to voice.

4.4 Implications

Our review contributes to the investigation of voice in action teams and has several implications. First, we provide a critical perspective on the treatment of voice in previous action team literature. The research suffers from heterogeneous conceptualizations and measurements, which indicates a need for a more standardized approach to voice research. Studies would benefit from explicitly defining voice variables. Furthermore, stronger consensus among studies, including conceptual approaches (e.g., definitions and the role of the recipient) and methodological approaches (e.g., standardized and validated instruments) would be important to increase the validity and comparability of results of investigations of voice in action teams.

Second, our review offers the opportunity to gain insight into the measurement instruments that have been used to assess voice in action teams. This contributes to an overview of existing methodological approaches and thereby supports the planning of future studies. Moreover, the overview might provide information on the advantages and disadvantages of instruments, indicating that behavioral observation could be more suitable than self-report (Noort et al. 2019) when examining voice in practice.

Third, training and interventions could benefit from the distinction between voice contents, such as promotive (e.g., suggestions and ideas) and prohibitive voice (e.g., preventing hazardous situations; Liang et al. 2012). Depending on the team situation (e.g., emergency situation), prohibitive voice might be more urgent and trainees could be encouraged to express it more assertively than promotive voice. As adequate responses to voice (e.g., leader’s explanation for rejecting voice) would be valuable with regard to promoting subsequent voice (King et al. 2019), it could be beneficial to organizations to train not only the sender’s voice but also the recipient’s response to critical feedback. Taking a step back, research on the reaction to voice itself would be valuable, including the question of what makes a reaction a good reaction. In sum, we would recommend a stronger focus on the recipient of voice. Finally, to investigate effects of the recipient’s response to voice, considering voice as dynamic team process would be useful. In this context, we suggest that voice research would benefit from better integrating emergent states such as team mental models or intra-team trust, which have been shown to play an important role in action teams (Burtscher and Manser 2012; Burtscher et al. 2018a, b). For example, the dynamics of voice and its relationship to team performance may well be contingent on the level of trust among team members.

4.5 Limitations and future research

Our work has several limitations. First, our study focused on voice in action teams and did not involve other team settings. Broadening the range of literature would have led to a more comprehensive conceptual and methodological overview. However, by highlighting the importance of voice in action teams, we concentrated on research in high-reliability environments. Second, we are aware of potential search terms that we did not employ in our literature search. For example, there are similar concepts to voice such as assertiveness or assertive communication that have been associated with error detection and challenging authority in earlier aviation literature (Chute and Wiener 1996; Orasanu et al. 1998). However, we decided to strictly follow the inclusion criteria and explicitly focus on the established concept of voice (Morrison 2011, 2014). Third, teams that work in high-reliability organizations, such as in healthcare, aviation, or military settings, do not necessarily always involve actual action team work. For example, questionnaires that are sent through wards in hospitals might be answered by individuals that do not deal directly with emergency situations. Another aspect leading to the limited generalizability of our results concerns the reviewed studies that were—apart from a few exceptions—mainly conducted in the healthcare domain. Finally, we investigated different types of voice measures but did not rate the quality of methods that were used (Prisma Checklist; Moher et al. 2009). However, the present review did not focus on evaluation of single studies, but instead aimed to provide a bigger picture of how voice has been treated conceptually and methodologically in action team literature.

In addition to the issues mentioned above, future research on voice in action teams might profit from considering the role of non-verbal behavior—both in expressing concerns as well as in receiving voice. In the context of healthcare action teams, non-verbal behaviors such as monitoring other team members (Burtscher et al. 2001) and hand gestures (Härgestam et al. 2016) have been shown to be important aspects of teamwork. Against this background, it would be worthwhile to investigate how specific hand gestures might relate to voice expression and effectiveness.

5 Conclusion

This is the first systematic review of the literature on voice in action teams, which also critically considers the treatment of voice in practice. First, our review highlights that concepts and methods are very heterogeneous. For this reason, we would like to emphasize the need for developing a shared understanding of voice in future studies such that a better comparability and integration of research findings will be possible. Second, by showing which instruments have been employed to measure voice, we hope to contribute to an overview—especially for practitioners—that supports future research on voice in action teams. Finally, our review indicates that high-reliability organizations could benefit from conceptualizing voice as a dynamic team process, which includes considering both sender as well as recipient. We hope that this review contributes to a more complete understanding of voice in action teams, particularly regarding the challenges associated with investigating voice in field settings. Ideally, the review should help closing the gap between research and practice and thus contribute to error reduction and improved organizational performance.

Notes

For simplicity, we use "voice" as an umbrella term.

We found 26 articles, each containing one study. McClean et al. (2018) represents an exception, as it includes two studies. In our review, we refer to McClean et al.'s study 1, as it is the only one that is set in an action team context (and therefore fulfills our selection criteria).

References

Alingh CW, Van Wijngaarden JDH, Van De Voorde K et al (2019) Speaking up about patient safety concerns: the influence of safety management approaches and climate on nurses’ willingness to speak up. BMJ Qual Saf 28:39–48. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2017-007163

Argyris C (1980) Making the undiscussable and its undiscussability discussable. Public Adm Rev 40:205–213. https://www.jstor.org/stable/975372

Argyris C, Schon D (1974) Theory in practice: increasing professional effectiveness. Jossey-Bass, Oxford

Ashford SJ, Sutcliffe KM, Christianson MK (2009) Speaking up and speaking out: the leadership dynamics of voice in organizations. In: Greenberg J, Edwards MS (eds) Voice and silence in organizations. Emerald Group Publishing, Bingley, pp 175–202

Baker DP, Day R, Salas E (2006) Teamwork as an essential component of high-reliability organizations. Health Serv Res 41:1576–1598. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00566.x

Barshi I, Bienefeld N (2018) When silence is not golden. In: Hagen J (ed) How could this happen? Managing errors in organizations. Springer Nature Switzerland AG, Berlin, pp 45–57

Bashshur MR, Oc B (2015) When voice matters: a multilevel review of the impact of voice in organizations. J Manage 41:1530–1554. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314558302

Beament T, Mercer SJ (2016) Speak up! Barriers to challenging erroneous decisions of seniors in anaesthesia. Anaesthesia 71:1332–1340. https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.13546

Belyanski I, Martin T, Prabhu A et al (2011) Poor resident-attending intraoperative communication may compromise patient safety. J Surg Res 171:386–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2011.04.011

Bienefeld N, Grote G (2012) Silence that may kill. Aviat Psychol Appl Hum Factors 2:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1027/2192-0923/a000021

Bienefeld N, Grote G (2014) Speaking up in ad hoc multiteam systems: individual-level effects of psychological safety, status, and leadership within and across teams. Eur J Work Organ Psychol 23:930–945. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2013.808398

Booth A, Sutton A, Papaioannou D (2016) Systematic approaches to a successful literature review, 2nd edn. SAGE Publications, London

Bould MD, Sutherland S, Sydor ST et al (2015) V. Residents’ reluctance to challenge negative hierarchy in the operating room: a qualitative study. Can J Anaesth 62:576–586. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-015-0364-5

Burris ER (2012) The risks and rewards of speaking up: managerial responses to employee voice. Acad Manag J 55:851–875. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.0562

Burris ER, Detert JR, Romney AC (2013) Speaking up vs. being heard: the disagreement around and outcomes of employee voice. Organ Sci 24:22–38. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1110.0732

Burris ER, Rockmann K, Kimmons Y (2017) The value of voice (to managers): employee identification and the content of voice. Acad Manag J 60:2099–2125. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2014.0320

Burt RS (1976) Interpretational confounding of unobserved variables in structural equation models. Sociol Methods Res 5:3–52

Burtscher MJ, Manser T (2012) Team mental models and their potential to improve teamwork and safety: a review and implications for future research in healthcare. Saf Sci 50:1344–1354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2011.12.033

Burtscher MJ, Kolbe M, Wacker A et al (2001) Interactions of team mental models and monitoring behaviors predict team performance in simulated anesthesia inductions. J Exp Psychol Appl 17:257–269. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025148

Burtscher MJ, Jordi-Ritz EM, Kolbe M (2018a) Differences in talking-to-the-room behaviour between novice and expert teams during simulated paediatric resuscitation: a quasi-experimental study. BMJ STEL 4:165–170. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjstel-2017-000268

Burtscher MJ, Meyer B, Jonas K et al (2018b) A time to trust? The buffering effect of trust and its temporal variations in the context of high-reliability teams. J Organ Behav. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2271

Chamberlin M, Newton DW, Lepine JA (2017) A meta-analysis of voice and its promotive and prohibitive forms: identification of key associations, distinctions, and future research directions. Pers Psychol 70:11–71. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12185

Chute RD, Wiener EL (1996) Cockpit-cabin communication: II. Shall we tell the pilots? Int J Aviat Psychol 6:211–231

Crant JM, Kim T, Wang J et al (2010) Dispositional antecedents of demonstration and usefulness of voice behavior. J Bus Psychol 26:285–297. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-010-9197-y

Detert JR, Burris ER (2007) Leadership behavior and employee voice: is the door really open? Acad Manag J 50:869–884. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMJ.2007.26279183

Detert JR, Edmondson AC (2011) Implicit voice theories: taken-for-granted rules of self-censorship at work. Acad Manag J 54:461–488

Edmondson A (2003) Speaking up in the operating room: how team leaders promote learning in interdisciplinary action teams. J Manag Stud 40:1419–1452. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6486.00386

Edmondson AC, Lei Z (2014) Psychological safety: the history, renaissance, and future of an interpersonal construct. Annu Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav 1:23–43. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091305

Edwards MS, Ashkanasy NM, Gardner J (2009) Deciding to speak up or to remain silent following observed wrongdoing: the role of discrete emotions and climate of silence. In: Greenberg J, Edwards MS (eds) Voice and silence in organizations. Emerald Group Publishing, Bingley, pp 83–109

European Union Aviation Safety Agency (2019) Easy Access Rules for Air Operations, Regulations (EU) No 965/2012.https://www.easa.europa.eu/sites/default/files/dfu/EasyAccessRuleforAirOperations-Oct2019.pdf

Farh CIC, Chen G (2018) Leadership and member voice in action teams: test of a dynamic phase model. J Appl Psychol 103:97–110. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000256

Fast NJ, Burris ER, Bartel CA (2014) Managing to stay in the dark: managerial self-efficacy, ego defensiveness, and the aversion to employee voice. Acad Manag J 57:1013–1034. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2012.0393

Flin R, O’Connor P, Mearns K (2002) Crew resource management: improving team work in high reliability industries. Team Perform Manag An Int J 8:68–78. https://doi.org/10.1108/13527590210433366

Flin R, Patey R, Glavin R, Maran N (2010) Anaesthetists’ non-technical skills. Br J Anaesth 105:38–44. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aeq134

Flin RH, O'Connor P, Crichton M (2008) Safety at the sharp end: a guide to non-technical skills. Ashgate Publishing Ltd

Friedman Z, Hayter MA, Everett TC et al (2015) Power and conflict: the effect of a superior’s interpersonal behaviour on trainees’ ability to challenge authority during a simulated airway emergency. Anaesthesia 70:1119–1129. https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.13191

Foushee HC, Helmreich RL (1993) Why crew resource management? Empirical and theoretical bases of human factors training. In: Weiner EL, Kanki BG, Helmreich RL (eds) Cockpit Resource Management. Academic Press, San Diego, pp 3–45

Gao L, Janssen O, Shi K (2011) Leader trust and employee voice: the moderating role of empowering leader behaviors. Leadersh Q 22:787–798. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2011.05.015

Grant AM, Hofmann DA, Carolina N (2011) Reversing the extraverted leadership advantage: the role of employee proactivity. Acad Manag J 54:528–550. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMJ.2011.61968043

Green B, Oeppen RS, Smith DW, Brennan PA (2017) Challenging hierarchy in healthcare teams: ways to flatten gradients to improve teamwork and patient care. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 55:449–453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjoms.2017.02.010

Guenter H, Schreurs B, van Emmerik IH, Sun S (2017) What does it take to break the silence in teams: authentic leadership and/or proactive followership? Appl Psychol 66:49–77. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12076

Härgestam M, Hultin M, Brulin C et al (2016) Trauma team leaders’ non-verbal communication: video registration during trauma team training. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 24:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13049-016-0230-7

Haynes S, Richard D, Kubany E (1995) Content validity in psychological assessment: a functional approach to concepts and methods. Psychol Assess 7:238–247. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.7.3.238

Healey AN, Undre S, Vincent CA (2004) Developing observational measures of performance in surgical teams. Qual Saf Heal Care 13:33–40. https://doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2004.009936

Howell RD, Breivik E, Wilcox JB (2007) Reconsidering formative measurement. Psychol Methods 12:205–218. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.12.2.205

Howell TM, Harrison DA, Burris ER, Detert JR (2015) Who gets credit for input? Demographic and structural status cues in voice recognition. J Appl Psychol 100:1765–1784. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000025

Ishak AW, Ballard DI (2012) Time to re-Group: a typology and nested phase model for action teams. Small Gr Res 43:3–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046496411425250

Islam G, Zyphur MJ (2005) Power, voice, and hierarchy: exploring the antecedents of speaking up in groups. Gr Dyn 9:93–103. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2699.9.2.93

Islam T, Ahmed I, Ali G (2019) Effects of ethical leadership on bullying and voice behavior among nurses: mediating role of organizational identification, poor working condition and workload. Leadersh Heal Serv 32:2–17. https://doi.org/10.1108/LHS-02-2017-0006

Kanki B (2019) Communication and crew resource management. In: Kanki B, Helmreich R, Anca J, eds. Crew Resource Management. 2nd edition. pp 111–146

King DD, Ryan AM, Van Dyne L (2019) Voice resilience: fostering future voice after non-endorsement of suggestions. J Occup Organ Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12275

Kipnis D, Schmidt SM, Wilkinson I (1980) Intraorganizational influence tactics: explorations in getting one's Way. J Appl Psychol 65:440–452

Klein KJ, Ziegert JC, Knight AP (2006) Dynamic delegation: action teams. Adm Sci Q 51:590–621. https://doi.org/10.2189/asqu.51.4.590

Knoll M, Wegge J, Unterrainer C et al (2016) Is our knowledge of voice and silence in organizations growing? Building bridges and (re)discovering opportunities. Ger J Hum Resour Manag 30:161–194. https://doi.org/10.1177/2397002216649857

Kobayashi H, Pian-Smith MCM, Sato M et al (2006) A cross-cultural survey of residents’ perceived barriers in questioning/challenging authority. Qual Saf Heal Care 15:277–283. https://doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2005.017368

Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Molla S (2000) To err is human: building a safer health system. National Academies Press, Washington

Kolbe M, Boos M (2019) Laborious but elaborate: the benefits of really studying team dynamics. Front Psychol 10:1–16. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01478

Kolbe M, Burtscher MJ, Wacker J et al (2012) Speaking up is related to better team performance in simulated anesthesia inductions: an observational study. Anesth Analg 115:1099–1108. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0b013e318269cd32

Kolbe M, Burtscher MJ, Manser T (2013) Co-ACT-A framework for observing coordination behaviour in acute care teams. BMJ Qual Saf 22:596–605. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001319

Kolbe M, Grote G, Waller MJ et al (2014) Monitoring and talking to the room: autochthonous coordination patterns in team interaction and performance. J Appl Psychol 99:1254–1267. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037877

Kozlowski SWJ (2015) Advancing research on team process dynamics: theoretical, methodological, and measurement considerations. Organ Psychol Rev 5:270–299. https://doi.org/10.1177/2041386614533586

Krenz HL, Burtscher MJ, Kolbe M (2019) “Not only hard to make but also hard to take:” team leaders’ reactions to voice. Grup Interaktion Organ Zeitschrift fur Angew Organ. 50:3–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11612-019-00448-2

Krenz HL, Burtscher MJ, Grande B, Kolbe M (2020) Nurses’ voice: the role of hierarchy and leadership. Leadersh Heal Serv 1:12–26. https://doi.org/10.1108/LHS-07-2019-0048

Leonard M, Graham S, Bonacum D (2004) The human factor: the critical importance of effective teamwork and communication in providing safe care. Qual Saf Health Care 13:i85–i90. https://doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2004.010033

Le Pine JA, Van Dyne L (2001) Voice and cooperative behavior as contrasting forms of contextual performance: evidence of differential relationships with big five personality characteristics and cognitive ability. J Appl Psychol 86:326–336. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-9010.86.2.326

Li AN, Liao H, Tangirala S, Firth BM (2017) The content of the message matters: the differential effects of promotive and prohibitive team voice on team productivity and safety performance gains. J Appl Psychol 102:1259–1270. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000215

Liang J, Farh CIC (2018) Differential implications of team member promotive and prohibitive voice on innovation performance in research and development project teams: a dialectic perspective. J Organ Behav. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2325

Liang J, Farh CIC, Farh JL (2012) Psychological antecedents of promotive and prohibitive Voice: a two-wave examination. Acad Manag J 55:71–92. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.0176

Liao ML, Etchegaray JM, Williams ST et al (2014) Assessing medical students’ perceptions of patient safety: the medical student safety attitudes and professionalism survey. Acad Med 89:343–351. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000124

Lin S, Johnson RE (2015) A suggestion to improve a day keeps your depletion away: examining promotive and prohibitive voice behaviors within a regulatory focus and ego depletion framework. J Appl Psychol 100:1381–1397. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000018

Lingard L, Espin S, Whyte S et al (2004) Communication failures in the operating room: an observational classification of recurrent types and effects. BMJ Qual Saf 13:330–334

Lyndon A, Sexton JB, Simpson K et al (2012) Predictors of likelihood of speaking up about safety concerns in labour and delivery. BMJ Qual Saf 21:791–799. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs.2010.050211

Marks MA, Zaccaro SJ, Mathieu JE (2000) Performance implications of leader briefings and team-interaction training for team adaptation to novel environments. J Appl Psychol 85:971–986. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.85.6.971

Martinez W, Etchegaray JM, Thomas EJ et al (2015) ‘Speaking up’ about patient safety concerns and unprofessional behaviour among residents: validation of two scales. BMJ Qual Saf. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004253

Martinez W, Lehmann LS, Thomas EJ et al (2017) Speaking up about traditional and professionalism-related patient safety threats: a national survey of interns and residents. BMJ Qual Saf 26:869–880. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2016-006284

Martínez-Córcoles M, Stephanou KD, Schöbel M (2018) Exploring the effects of leaders’ individualized consideration in extreme contexts. J Risk Res. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2018.1517385

McClean E, Martin SR, Emich KJ, Woodruff CO (2018) The social consequences of voice: an examination of voice type and gender on status and subsequent leader emergence. Acad Manag J 61:1869–1891. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2016.0148

Milliken FJ, Lam N (2009) Making the decision to speak up or to remain silent: implications for organizational learning. In: Greenberg J, Edwards MS (eds) Voice and silence in organizations. Emerald Group Publishing, Bingley, pp 225–244

Milliken FJ, Morrison EW, Hewlin PF (2003) An exploratory study of employee silence: issues that employees don’t communicate upward and why. J Manag Stud. 40:1453–1476. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6486.00387

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J et al (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement (reprinted from annals of internal medicine). Phys Ther 89:873–880. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Moosbrugger H, Kelava A (2012) Qualitätsanforderungen an einen psychologischen Test (Testgütekriterien). In: Testtheorie und Fragebogenkonstruktion. pp 1–30

Morrison E (2011) Employee voice behavior: integration and directions for future research. Acad Manag Ann 5:373–412. https://doi.org/10.1080/19416520.2011.574506

Morrison E (2014) Employee voice and silence. Annu Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav 1:173–197. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091328

Morrison E, Milliken FJ (2000) Organizational silence: a barrier to change and development in a pluralistic world. Aca Manag Rev 25:706–725. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2000.3707697

Morrison EW, Wheeler-Smith SL, Kamdar D (2011) Speaking up in groups: a cross-level study of group voice climate and voice. J Appl Psychol 96:183–191. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020744

Morrow KJ, Gustavson AM, Jones J (2016) Speaking up behaviours (safety voices) of healthcare workers: a metasynthesis of qualitative research studies. Int J Nurs Stud 64:42–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2016.09.014

Nembhard IM, Edmondson AC (2006) Making it safe: the effects of leader inclusiveness and professional status on psychological safety and improvement efforts in health care teams. J Organ Behav 27:941–966. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.413

Ng TWH, Hsu DY, Parker SK (2019) Received respect and constructive voice: the roles of proactive motivation and perspective taking. Advance online publication, J Manag Stud. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206319834660

Noort MC, Reader TW, Gillespie A (2019) Speaking up to prevent harm: a systematic review of the safety voice literature. Saf Sci 117:375–387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2019.04.039

O’Connor P, Long WM (2011) The development of a prototype behavioral marker system for US Navy officers of the deck. Saf Sci 49:1381–1387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2011.05.009

O’Connor P, Campbell J, Newon J et al (2008) Crew resource management training effectiveness: a meta-analysis and some critical needs. Int J Aviat Psychol 18:353–368. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508410802347044

O’Connor P, Byrne D, Dea AO et al (2013) “Excuse me”: teaching interns to speak up. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 39:426–431. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1553-7250(13)39056-4

O’Connor P, Jones DW, McCauley ME et al (2012) An evaluation of the effectiveness of the U.S. Navy’s Crew Resource Management program. Int J Hum Factors Ergon 1:21–40. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJHFE.2012.045272

Okuyama A, Wagner C, Bijnen B (2014) Speaking up for patient safety by hospital-based health care professionals: a literature review. BMC Health Serv Res 14:1–8. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6963/14/61

Omura M, Maguire J, Levett-Jones T et al (2017) The effectiveness of assertiveness communication training programs for healthcare professionals and students: a systematic review. Int J Nurs 76:120–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.09.001

Oner C, Fisher N, Atallah F et al (2018) Simulation-based education to train learners to “speak up” in the clinical environment. Simul Healthc J Soc Simul Healthc 13:404–412. https://doi.org/10.1097/SIH.0000000000000335

Orasanu J, Fischer U, McDonnel LK, et al (1998) How do flight crews detect and prevent errors? Findings from a flight simulation study. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society, 42nd annual meeting

Pattni N, Bould MD, Hayter MA et al (2017) Gender, power and leadership: the effect of a superior’s gender on respiratory therapists’ ability to challenge leadership during a life-threatening emergency. Br J Anaesth 119:697–702. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aex246

Pattni N, Arzola C, Malavade A et al (2019) Challenging authority and speaking up in the operating room environment: a narrative synthesis. Br J Anaesth 122:233–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bja.2018.10.056

Pian-Smith MCM, Simon R, Minehart RD et al (2009) Teaching residents the two-challenge rule: a simulation-based approach to improve education and patient safety. Simul Healthc 4:84–91. https://doi.org/10.1097/SIH.0b013e31818cffd3

Pinder CC, Harlos KP (2001) Employee silence: quiescence and acquiescence as responses to perceived injustice. Research in personnel and human resources management. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 331–369

Raemer DB, Kolbe M, Minehart RD et al (2016) Improving anesthesiologists’ ability to speak up in the operating room: a randomized controlled experiment of a simulation-based intervention and a qualitative analysis of hurdles and enablers. Acad Med 91:530–539. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001033

Richard A, Pfeiffer Y, Schwappach D (2017) Development and psychometric evaluation of the speaking up about patient safety questionnaire. J Patient Saf. https://doi.org/10.1097/PTS.0000000000000415

Robb A, White C, Cordar A et al (2015) A comparison of speaking up behavior during conflict with real and virtual humans. Comput Human Behav 52:12–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.05.043

Salas E, Reyes DL, McDaniel SH (2018) The science of teamwork: progress, reflections, and the road ahead. Am Psychol 73:93–600. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000334

Salazar MJB, Minkoff H, Bayya J et al (2014) Influence of surgeon behavior on trainee willingness to speak up: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Coll Surg 219:1001–1007. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2014.07.933

Salas E, Cannon-Bowers AJ (2001) The science of training: a decade of progress. Annu Rev Psychol 52:471–99. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.471

Sayre MM, McNeese-Smith D, Leach LS (2012) An educational intervention to behaviors in nurses and improve patient safety. 27:154–160. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCQ.0b013e318241d9ff

Schick CJ, Weiss M, Kolbe M et al (2015) Simulation with PARTS (Phase-augmented research and training scenarios): a structure facilitating research and assessment in simulation. Simul Healthc 10:178–187. https://doi.org/10.1097/SIH.0000000000000085

Schwappach D, Gehring K (2014) Silence that can be dangerous: a vignette study to assess healthcare professionals’ likelihood of speaking up about safety concerns. 9:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0104720

Schwappach D, Richard A (2018) Speak up-related climate and its association with healthcare workers’ speaking up and withholding voice behaviours: a cross-sectional survey in Switzerland. BMJ Qual Saf 27:827–835. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2017-007388

Sexton JB, Helmreich RL, Neilands TB et al (2006) The safety attitudes questionnaire: psychometric properties, benchmarking data, and emerging research. BMC Health Serv

Sherf EN, Sinha R, Tangirala S, Awasty N (2018) Centralization of member voice in teams: its effects on expertise utilization and team performance. J Appl Psychol 103:813–827. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000305

Smits M, Christiaans-Dingelhoff I, Wagner C et al (2008) The psychometric properties of the ‘Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture’ in Dutch hospitals. BMC Health Serv Res 8:230. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-8-230

Srivastava R (2013) Speaking up-when doctors navigate medical hierarchy. N Engl J Med 368:302–5. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1212410

Suddaby R (2010) Editor’s comments: construct clarity in theories of management and organization. Acad Manag Rev 35:346–357. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2010.51141319

Sundstrom E, McIntyre M, Halfhill T, Richards H (2000) Work groups: from the hawthorne studies to work teams of the 1990s and beyond. Gr Dyn Theory, Res Pract 4:44–67. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2699.4.1.44

Sydor DT, Bould MD, Naik VN et al (2013) Challenging authority during a life-threatening crisis: the effect of operating theatre hierarchy. 110:463–471. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aes396

Tangirala S, Ramanujam R (2009) The sound of loyalty: voice or silence? In: Greenberg J, Edwards MS (eds) Voice and silence in organizations. Emerald Group Publishing, Bingley, pp 203–224

Tangirala S, Ramanujam R (2012) Ask and you shall hear (but not always): examining the relationship between manager consultation and employee voice. Pers Psychol 65:251–282. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2012.01248.x

U.S. Department of the Air Force (2019) Air Force Guidance Memorandum to AFI 11-290, Cockpit/crew resource management program

Van Dyne L, LePine J (1998) Helping and voice extra-role behaviors: evidence of construct and predictive validity. Acad Manag J 41:108–119. https://doi.org/10.5465/256902

Van Dyne L, Cummings LL, Parks JM (1995) Extra-role behaviors: in pursuit of construct and definitional clarity (A bridge over muddied waters). In: Cummings LL, Staw BM (eds) Research in organizational behavior. JAI Press, Greenwich, pp 215–285

Waller MJ, Kaplan SA (2018) Systematic behavioral observation for emergent team phenomena: key considerations for quantitative video-based approaches. Organ Res Methods 21:500–515. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428116647785

Weick KE, Sutcliffe KM, Obstfeld D (1999) Organizing for high reliability: processes of collective mindfulness. Res Organ Behav 3:81–123

Weiss M, Kolbe M, Grote G et al (2014) Agency and communion predict speaking up in acute care teams. Small Gr Res 45:290–313. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046496414531495

Weiss M, Kolbe M, Grote G et al (2017) Why didn’t you say something? Effects of after-event reviews on voice behaviour and hierarchy beliefs in multi-professional action teams. Eur J Work Organ Psychol 26:66–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2016.1208652

Weiss M, Kolbe M, Grote G et al (2018) We can do it! Inclusive leader language promotes voice behavior in multi-professional teams. Leadersh Q 29:389–402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2017.09.002

Whiting SW, Maynes TD, Podsakoff NP, Podsakoff PM (2012) Effects of message, source, and context on evaluations of employee voice behavior. J Appl Psychol 97:159–182. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024871

Wilkinson A, Barry M, Morrison E (2019) Toward an integration of research on employee voice. Hum Resour Manag Rev 3:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2018.12.001

Williams M, Hevelone N, Alban RF et al (2010) Measuring communication in the surgical ICU: better communication equals better care. J Am Coll Surgeons 210:17–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.09

Acknowledgement

: Open access funding provided by University of Zurich. Schweizerischer Nationalfonds zur Förderung der Wissenschaftlichen Forschung.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix I Overview: voice definitions

Appendix I Overview: voice definitions

Author, year | Voice definition |

|---|---|

Bienefeld and Grote (2012) | “Speaking up in high-risk contexts is defined as an upward voice directed from lower to higher status individuals within and across teams, that challenges the status quo, to avert or mitigate errors” (p. 1) |

Bienefeld and Grote (2014) | “Speaking up is defined as un upward voice, directed from subordinates to superiors, that challenges actions or decisions of superiors”a (p. 930) |

Pian-Smith et al. (2009) | No definition |

Kolbe et al. (2012) | “In accordance with the literature, we define speaking up as explicitly communicating task-relevant observations, requesting clarification, or explicitly challenging or correcting a task-relevant decision or procedure”a (p. 2) |

Sydor et al. (2013) | No definition |

Weiss et al. (2014) | “By combining Morrison’s (2011) and Edmonson’s (1999) definition of speaking up, we use both terms interchangeably and defined speaking up as explicit communication of suggestions, problems, opinions or doubts that challenge the status quo” (p. 291) |

Robb et al. (2015) | No definition |

Friedman et al. (2015) | No definition |

Raemer et al. (2016) | No definition |

Beament and Mercer (2016) | “For the purposes of this article, we define ‘speaking up’ as communicating other team members’ doubts, differing opinions or potential problems about decision or course of action in medical care” (p. 1332) |

Pattni et al. (2017) | No definition |