Abstract

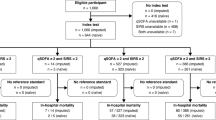

The aim of this study was to determine the accuracy of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), quick Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment (qSOFA) score and GYM score to predict 30-day mortality in older non-severely dependent patients attended for an episode of infection in the emergency department (ED). We performed an analytical, observational, prospective cohort study including patients 75 years of age or older, without severe functional dependence, attended for an infectious process in 69 Spanish EDs for 2-day three-seasonal periods. Demographic, clinical and analytical data were collected. The primary outcome was 30-day mortality after the index event. We included 1071 patients, with a mean age of 83.6 [standard deviation (SD) 5.6] years; 544 (50.8%) were men. Seventy-two patients (6.5%) died within 30 days. SIRS criteria ≥ 2 had a sensitivity of 65% [95% confidence interval (CI) 53.1–75.9] and a specificity of 49% (95% CI 46.0–52.3), a qSOFA score ≥ 2 had a sensitivity of 28% (95% CI 18.2–39.8) and a specificity of 94% (95% CI 91.9–95.1), and a GYM score ≥ 1 had a sensitivity of 81% (95% CI 69.2–88.6) and a specificity of 45% (95% CI 41.6–47.9). A GYM score ≥ 1 and a qSOFA score ≥ 2 were the cut-offs with the highest sensitivity (p < 0.001) and specificity (p < 0.001), respectively. The area under the curve (AUC) was 0.73 (95% CI 0.66–0.79; p < 0.001) for the GYM score, 0.69 (95% CI 0.61–0.76; p < 0.001) for the qSOFA score and 0.65 (95% CI 0.59–0.72; p < 0.001) for SIRS. A GYM score ≥ 1 may be the most sensitive score and a qSOFA score ≥ 2 the most specific score to predict 30-day mortality in non-severely dependent older patients attended for acute infection in EDs.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Angus DC, Linde-Zwirble WT, Lidicker J, Clermont G, Carcillo J, Pinsky MR (2001) Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Crit Care Med 29:1303–1310

Martin GS, Mannino DM, Eaton S, Moss M (2003) The epidemiology of sepsis in the United States from 1979 through 2000. N Engl J Med 348:1546–1554

Martínez Ortiz de Zárate M, González del Castillo J, Julián Jiménez A, Piñera Salmerón P, Llopis Roca F, Guardiola Tey JM et al (2013) Epidemiology of infections treated in hospital emergency departments and changes since 12 years earlier: the INFURG study of the Spanish Society of Emergency Medicine (SEMES). Emergencias 25:368–378

Kaukonen KM, Bailey M, Pilcher D, Cooper DJ, Bellomo R (2015) Systemic inflammatory response syndrome criteria in defining severe sepsis. N Engl J Med 372:1629–1638

Williams JM, Greenslade JH, Chu K, Brown AF, Lipman J (2016) Severity scores in emergency department patients with presumed infection: a prospective validation study. Crit Care Med 44:539–547

Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M et al (2016) The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA 315:801–810

Freund Y, Lemachatti N, Krastinova E, Van Laer M, Claessens YE, Avondo A et al (2017) Prognostic accuracy of Sepsis-3 criteria for in-hospital mortality among patients with suspected infection presenting to the emergency department. JAMA 317:301–308

Williams JM, Greenslade JH, McKenzie JV, Chu K, Brown AF, Lipman J (2017) Systemic inflammatory response syndrome, quick Sequential Organ Function Assessment, and organ dysfunction: insights from a prospective database of ED patients with infection. Chest 151:586–596. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2016.10.057

Martín-Sánchez FJ, González del Castillo J (2015) Sepsis in the elderly: are hospital emergency departments prepared? Emergencias 27:73–74

Opal SM, Girard TD, Ely EW (2005) The immunopathogenesis of sepsis in elderly patients. Clin Infect Dis 41:S504–S512

Martin GS, Mannino DM, Moss M (2006) The effect of age on the development and outcome of adult sepsis. Crit Care Med 34:15–21

González Del Castillo J, Escobar-Curbelo L, Martínez-Ortíz de Zárate M, Llopis-Roca F, García-Lamberechts J, Moreno-Cuervo Á et al (2017) GYM score: 30-day mortality predictive model in elderly patients attended in the emergency department with infection. Eur J Emerg Med 24:183–188

Seymour CW, Liu VX, Iwashyna TJ, Brunkhorst FM, Rea TD, Scherag A et al (2016) Assessment of clinical criteria for sepsis: for the Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA 315:762–774

Williams JM, Greenslade JH, McKenzie JV, Chu KH, Brown A, Paterson D et al (2011) A prospective registry of emergency department patients admitted with infection. BMC Infect Dis 11:27

Tudela P, Maria Mòdol J (2015) On hospital emergency department crowding. Emergencias 27:113–120

Monclús Cols E, Capdevila Reniu A, Roedberg Ramose D, Pujol Fontrodona G, Ortega Romero M (2016) Management of severe sepsis and septic shock in a tertiary care urban hospital emergency department: opportunities for improvement. Emergencias 28:229–234

Cohen JF, Korevaar DA, Altman DG, Bruns DE, Gatsonis CA, Hooft L et al (2016) STARD 2015 guidelines for reporting diagnostic accuracy studies: explanation and elaboration. BMJ Open 6:e012799

Churpek MM, Snyder A, Han X, Sokol S, Pettit N, Howell MD et al (2017) Quick Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment, systemic inflammatory response syndrome, and early warning scores for detecting clinical deterioration in infected patients outside the intensive care unit. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 195:906–911

Collins GS, Reitsma JB, Altman DG, Moons KG (2015) Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis (TRIPOD): the TRIPOD statement. Ann Intern Med 162:55–63

El Solh AA, Akinnusi ME, Alsawalha LN, Pineda LA (2008) Outcome of septic shock in older adults after implementation of the sepsis “bundle”. J Am Geriatr Soc 56:272–278

Doerfler ME, D’Angelo J, Jacobsen D, Jarrett MP, Kabcenell AI, Masick KD et al (2015) Methods for reducing sepsis mortality in emergency departments and inpatient units. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 41:205–211

Maxim LD, Niebo R, Utell MJ (2014) Screening tests: a review with examples. Inhal Toxicol 26:811–828

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

All authors contributed to the development of the study protocol. JGdC and FJMS planned the study concept and design. JGdC obtained ethics committee approval and performed the study supervision. The other authors and members of the Infectious Disease Group of the Spanish Emergency Medicine Society collected all data. FJMS and JGdC analysed and interpreted the data. FJMS and JGdC prepared the first manuscript draft. All authors contributed to manuscript revision and all approved of the final document.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

No financial support was used. The promoter of this study has been the Infectious Disease Group of the Spanish Emergency Medicine Society. This group has received financial support from Merck, Tedec-Meiji, Pfizer, Thermo Fisher, Laboratorios Rubio and Novartis in the last year to organise conferences and group meetings. None of the authors has received any financial compensation.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The Ethical Committee of the Clínico San Carlos Hospital approved the study.

Informed consent

All the patients or tutors provided informed consent to participate in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

González del Castillo, J., Julian-Jiménez, A., González-Martínez, F. et al. Prognostic accuracy of SIRS criteria, qSOFA score and GYM score for 30-day-mortality in older non-severely dependent infected patients attended in the emergency department. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 36, 2361–2369 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-017-3068-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-017-3068-7