Abstract

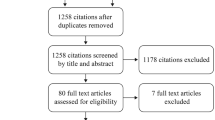

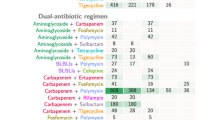

Carbapenems have not been comprehensively compared in clinical trials with fourth-generation cephalosporins (4GC) and antipseudomonal penicillins (APP) in the treatment of severe infections (SI) and febrile neutropenia (FN). A systematic review of CENTRAL, EMBASE, MEDLINE and JICST-EPlus for randomised controlled trials was conducted to establish the currently available evidence. Database searching was supplemented by hand searching and contacting conference organisers. Searching was completed in November 2006 and no restriction was placed on the language of publication. Data were extracted on clinical response, bacteriologic response, all-cause mortality and adverse events. Of the 265 papers identified, 12 were appropriate for meta-analysis (four 4GC and eight APP). The results showed that carbapenems are associated with a significant reduction in all-cause mortality (relative risk 0.62, 95% confidence interval: 0.41 to 0.95; p=0.03) compared to APP in the treatment of SI, and withdrawals due to adverse events (RR 0.65, 95% CI: 0.45 to 0.96; p=0.03) are also less common. When compared in the treatment of FN, carbapenems are associated with a significant increase in clinical response during the initial 72 h of treatment (RR 1.37, 95% CI: 1.09 to 1.74; p=0.008) and bacteriologic response (RR 1.73, 95% CI: 1.03 to 2.89; p=0.04). For all other outcomes, including all comparisons with 4GC, there were no significant differences between treatments. The use of carbapenems rather than APP could reduce mortality and, by simplifying treatment decisions, reduce the time before patients receive appropriate antibiotic treatment. The currently available evidence is insufficient for distinguishing between carbapenems and 4GC.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Department of Health (2003) Winning ways: working together to reduce healthcare associated infection in England. Department of Health, London

National Audit Office (2000) The management and control of hospital acquired infection in acute NHS trusts in England. The Stationery Office, London

Donowitz LG, Wenzel RP, Hoyt JW (1982) High risk of hospital-acquired infection in the ICU patient. Crit Care Med 10:355–357

Wenzel RP, Thompson RL, Landry SM et al (1983) Hospital-acquired infections in intensive care unit patients: an overview with emphasis on epidemics. Infect Control 4:371–375

Kollef MH, Sherman G, Ward S et al (1999) Inadequate antimicrobial treatment of infections: a risk factor for hospital mortality among critically ill patients. Chest 115:462–474

Rello J, Gallego M, Mariscal D et al (1997) The value of routine microbial investigation in ventilator-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Care Med 156:196–200

Kollef MH, Ward S (1998) The influence of mini-BAL cultures on patient outcomes: implications for the antibiotic management of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Chest 113:412–420

Meehan TP, Fine MJ, Krumholz HM et al (1997) Quality of care, process, and outcomes in elderly patients with pneumonia. JAMA 278:2080–2084

Houck PM, Bratzler DW, Nsa W et al (2004) Timing of antibiotic administration and outcomes for Medicare patients hospitalised with community-acquired pneumonia. Arch Intern Med 164:637–644

Kumar A, Roberts D, Wood KE et al (2006) Duration of hypotension before initiation of effective antimicrobial therapy is the critical determinant of survival in human septic shock. Crit Care Med 34:1589–1596

American Thoracic Society (1995) Hospital-acquired pneumonia in adults: diagnosis, assessment of severity, initial antimicrobial therapy, and preventative strategies. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 153:1711–1725

American Thoracic Society (2001) Guidelines for the management of adults with community-acquired pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 163:1730–1754

American Thoracic Society (2005) Guidelines for the management of adults with hospital-acquired, ventilator-associated, and healthcare-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 171:388–416

Solomkin JS, Mazuski JE, Baron EJ et al (2003) Guidelines for the selection of anti-infective agents for complicated intra-abdominal infections. Clin Infect Dis 37:997–1005

Stevens DS, Bisno AL, Chambers HF et al (2005) Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft-tissue infections. Clin Infect Dis 41:1373–1406

British Thoracic Society (2004) BTS guidelines for the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults—2004 update. Available online at: http://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/c2/uploads/MACAPrevisedApr04.pdf

Bodmann KF (2005) Current guidelines for the treatment of severe pneumonia and sepsis. Chemotherapy 51:227–233

Paul M, Silbiger I, Grozinsky S et al (2006) Beta lactam antibiotic monotherapy versus beta lactam-aminoglycoside antibiotic combination therapy for sepsis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev Issue 1. Art. No.: CD003344 DOI 10.1002/14651858.CD003344.pub2

Craig WA, Ebert SC (1994) Antimicrobial therapy in Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. In: Baltch AL, Smith RP (eds) Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections and treatment. Marcel Dekker, New York, pp 441–517

Goldstein FW (2002) Cephalosporinase induction and cephalosporin resistance: a longstanding misinterpretation. Clin Microbial Infect 8:823–825

Khan KS, Popay J, Kleijnen (2001) Development of a review protocol. In: Undertaking systematic reviews of research on effectiveness. CRD Report Number 4, 2nd edn. Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, York

Higgins JPT, Green S (eds) (2005) Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions 4.2.5 [updated May 2005]. In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 3. Wiley, Chichester, UK

Silagy C (1993) Developing a register of randomised controlled trials in primary care. BMJ 306:897–900

Chapman TM, Perry CM (2003) Cefepime: a review of its use in the management of hospitalized patients with pneumonia. Am J Respir Med 2:75–107

Timmers GJ, van Vuurden DG, Swart EL et al (2005) Cefpirome as empirical treatment for febrile neutropenia in patients with hematologic malignancies. Haematologica 90:1005–1006

Norrby SR, Geddes AM, Shah PM (1998) Randomized comparative trial of cefpirome versus ceftazidime in the empirical treatment of suspected bacteraemia or sepsis. Multicentre Study Group. J Antimicrob Chemother 42:503–509

BNF 52 (September 2006) Home page at: http://www.bnf.org (last accessed October 2006)

Occhipinti DJ, Pendland SL, Schoonover LL et al (1997) Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of two multiple-dose piperacillin-tazobactam regimens. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 41:2511–2517

Merck Sharp, Dohme Limited (2005) Invanz® summary of product characteristics, October 2005. Available at: http://emc.medicines.org.uk (last accessed October 2006)

Merck Sharp, Dohme Limited (2005) Primaxin® summary of product characteristics, October 2005. Available at: http://emc.medicines.org.uk (last accessed October 2006)

Hurst M, Lamb HM (2000) Meropenem: a review of its use in patients in intensive care. Drugs 59:653–680

Chalmers TC, Celano P, Sacks HS et al (1983) Bias in treatment assignment in controlled clinical trials. N Engl J Med 309:1358–1361

Schulz KF, Chalmers I, Hayes RJ et al (1995) Empirical evidence of bias. Dimensions of methodological quality associated with estimates of treatment effects in controlled trials. JAMA 273:408–412

Moher D, Pham B, Jones A et al (1998) Does quality of reports of randomised trials affect estimates of intervention efficacy reported in meta-analyses? Lancet 352:609–613

Shefet D, Robenshtok E, Paul M et al (2005) Empirical atypical coverage for inpatients with community-acquired pneumonia: systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med 165:1992–2000

Review Manager (RevMan) version 4.2.8 for Windows [computer program] (2003) The Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, England

StatsDirect Ltd. (2002) StatsDirect statistical software. StatsDirect Ltd., England. Home page at: http://www.statsdirect.com)

Petitti DB (2000) Meta-analysis, decision analysis, and cost-effectiveness analysis: methods for quantitative synthesis in medicine, 2nd edn. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M et al (1997) Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 315:629–634

Solomkin JS, Yellin AE, Rotstein OD et al (2003) Ertapenem versus piperacillin/tazobactam in the treatment of complicated intraabdominal infections: results of a double-blind, randomized comparative phase III trial. Ann Surg 237:235–245

Zanetti G, Bally F, Greub G et al (2003) Cefepime versus imipenem-cilastatin for treatment of nosocomial pneumonia in intensive care unit patients: a multicenter, evaluator-blind, prospective, randomized study. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 47:3442–3447

Raad II, Escalante C, Hachem RY et al (2003) Treatment of febrile neutropenic patients with cancer who require hospitalization: a prospective randomized study comparing imipenem and cefepime. Cancer 98:1039–1047

Cherif H, Björkholm M, Engervall P et al (2004) A prospective, randomized study comparing cefepime and imipenem-cilastatin in the empirical treatment of febrile neutropenia in patients treated for haematological malignancies. Scand J Infect Dis 36:593–600

Niinikoski J, Havia T, Alhava E et al (1993) Piperacillin/tazobactam versus imipenem/cilastatin in the treatment of intra-abdominal infections. Surg Gynecol Obstet 176:255–261

Klein SR, Clark K, Speth J et al (1999) A randomized, double-blind, multicenter comparison of piperacillin-tazobactam (4 g/500 mg) and imipenem/cilastatin (1 g/1 g) administered intravenously every eight hours to treat intra-abdominal infections in hospitalized patients. Presented at the 37th Annual Meeting of the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA’99), Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, November 1999

Graham DR, Lucasti C, Málafaia O et al (2002) Ertapenem once daily versus piperacillin-tazobactam 4 times per day for treatment of complicated skin and skin-structure infections in adults: results of a prospective, randomized, double-blind multicenter study. Clin Infect Dis 34:1460–1468

Roy S, Higareda I, Angel-Muller E et al (2003) Ertapenem once a day versus piperacillin-tazobactam every 6 hours for treatment of acute pelvic infections: a prospective, multicenter, randomized, double-blind study. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol 11:27–37

Dela Pena AS, Asperger W, Köckerling F et al (2006) Efficacy and safety of ertapenem versus piperacillin-tazobactam for the treatment of intra-abdominal infections requiring surgical intervention. J Gastrointest Surg 10:567–574

Schmitt DV, Leitner E, Welte T et al (2006) Piperacillin/tazobactam vs imipenem/cilastatin in the treatment of nosocomial pneumonia—a double blind prospective multicentre study. Infection 34:127–134

Namias N, Solomkin JS, Jensen EH et al (2007) Randomized, multicenter, double-blind study of efficacy, safety, and tolerability of intravenous ertapenem versus piperacillin/tazobactam in treatment of complicated intra-abdominal infections in hospitalized adults. Surg Infect 8:15–28

Oppenheim BA, Morgenstern GR, Chang J et al (2001) Safety and efficacy of piperacillin/tazobactam versus meropenem in the treatment of febrile neutropenia. J Infect 43:A67

Reich G, Cornely OA, Sandherr M et al (2005) Empirical antimicrobial monotherapy in patients after high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation: a randomised, multicentre trial. Brit J Haematol 130:265–270

Fukushima R, Matsushima T, Kawane H et al (1986) A comparative study of MK-0787/MK0-0791 and piperacillin against respiratory tract infections. J Jpn Assoc Infect Dis 60:345–374

Brismar B, Malmborg AS, Tunevall G et al (1992) Piperacillin-tazobactam versus imipenem-cilastatin for treatment of intra-abdominal infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 36:2766–2773

Jhee SS, Gill MA, Yellin AE et al (1995) Pharmacoeconomics of piperacillin/tazobactam and imipenem/cilastatin in the treatment of patients with intra-abdominal infections. Clin Therapeu 17:126–135

Jaccard C, Troillet N, Harbarth S et al (1998) Prospective randomized comparison of imipenem-cilastatin and piperacillin-tazobactam in nosocomial pneumonia or peritonitis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 42:2966–2972

Marra F, Reynolds R, Stiver G et al (1998) Piperacillin/tazobactam versus imipenem: a double-blind, randomized formulary feasibility study at a major teaching hospital. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 31:355–368

Allo MD, Bennion RS, Kathir K et al (1999) Ticarcillin/clavulanate versus imipenem/cilistatin for the treatment of infections associated with gangrenous and perforated appendicitis. Am Surg 65:99–104

Bradford PA, Testa RT, Clark K et al (1999) Randomised, double-blind comparison efficacy study of piperacillin/tazobactam (PTZ) and imipenem/cilastatin (IPM) administered intravenously q8h to treat intra-abdominal patients (IAI). Presented at the 39th Annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy (ICAAC’99), San Francisco, California, September 1999

Naber KG, Savov O, Slamen HC (2002) Piperacillin 2 g/tazobactam 0.5 g is as effective as imipenem 0.5 g/cilastatin 0.5 g for the treatment of acute uncomplicated pyelonephritis and complicated urinary tract infections. Int J Antimicrob Agents 19:95–103

Erasmo AA, Crisostomo AC, Yan L-N et al (2004) Randomized comparison of piperacillin/tazobactam versus imipenem/cilastatin in the treatment of patients with intra-abdominal infection. Asian J Surg 27:227–235

Lipsky BA, Armstrong DG, Citron DM et al (2005) Ertapenem versus piperacillin/tazobactam for diabetic foot infections (SIDESTEP): prospective, randomised, controlled, double-blinded, multicentre trial. Lancet 366:1695–1703

Biron P, Fuhrmann C, Kheder R et al (1997) Cefepime (CEF) vs imipenem-cilastatin (IMP) as empiric monotherapy in 400 febrile patients with short duration neutropenia. Presented at the 37th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy (ICAAC’97), Toronto, Ontario, Canada, September/October 1997

Cornely OA, Reichert D, Buchheidt D et al (2001) Three-armed multicenter randomized study on the empiric treatment of neutropenic fever in a high risk patient population (PEG Study III). Abstract presented at the 41st Interscience Conference on Antimicrobials and Chemotherapy (ICAAC 2001), Chicago, Illinois, December 2001

Tamura K, Matsuoka H, Tsukada J et al (2002) Cefepime or carbapenem treatment for febrile neutropenia as a single agent is as effective as a combination of 4th-generation cephalosporin + aminoglycosides: comparative study. Am J Hematol 71:248–255

Paul M, Yahav D, Fraser A et al (2006) Empirical antibiotic monotherapy for febrile neutropenia: systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled randomized trials. J Antimicrobial Chemother 57:176–189

Figuera A, Rivero N, Pajuelo F et al (2001) Comparative study of piperacillin/tazobactam versus imipenem/cilastatin in febrile neutropenia (1994–1996). Med Clin (Barc) 116:610–611

Simmonds MC, Higgins JPT, Stewart LA et al (2005) Meta-analysis of individual patient data from randomized trials: a review of methods used in practice. Clin Trials 2:209–217

Keating GM, Perry CM (2005) Ertapenem: a review of its use in the treatment of bacterial infections. Drugs 65:2151–2178

Acknowledgements

SJE and CEE are employees of AstraZeneca UK Ltd., the distributor of the carbapenem, Meronem®, who provided some support for their work on this review. SW and MJC are both funded by the UK Department of Health and received no support or funding from AstraZeneca UK Ltd.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Edwards, S.J., Clarke, M.J., Wordsworth, S. et al. Carbapenems versus other beta-lactams in treating severe infections in intensive care: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 27, 531–543 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-008-0472-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-008-0472-z