Abstract

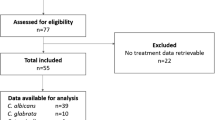

Candidemia is an increasing complication of the care of complex patients. Adherence to Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) guidelines for the treatment of candidemia was investigated to assess the impact of compliance on outcomes of therapy. Data on the epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment of patients with invasive fungal infections (IFIs) was extracted from the PATH Alliance registry, a prospective, multicenter, observational database of invasive fungal infections. Patients with proven candidemia were evaluated for adherence to the IDSA guidelines in terms of choice, dosage, and duration of antifungal therapy. Removal of central venous catheters and time to treatment initiation were assessed. Four-week survival data were compared. Of the 418 patients with candidemia who were included in the study, 361 patients with the necessary data sets were identified, of whom 262 (72.6%) were treated within the IDSA guidelines for the treatment of candidemia (IDSA group); the remaining 99 (27.4%) patients received treatment different from the guidelines (non-IDSA group). Kaplan-Meier (KM) survival analysis for patients in the IDSA and non-IDSA group showed mortality rates of 21.9 and 13.6%, respectively; the difference between the two groups was not statistically significant (P = 0.093). Following the exclusion of patients requiring mechanical ventilation or acute cardiac support, the modified survival KM curves were similar between the two groups. Significantly more patients in the IDSA group required mechanical ventilation and tunneled central catheters, had a concomitant IFI, and received caspofungin. The duration of treatment and inappropriate dosing did not appear to have had a significant impact on survival. Most of the deviations from IDSA guidelines were due to the inappropriate duration and dosing of therapy. No significant difference in mortality was noted between the IDSA and non-IDSA groups. The basis of these differences merit further study.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Marr KA (2004) Invasive Candida infections: the changing epidemiology. Oncology 18:9–14

Wey SB, Mori M, Pfaller MA, Woolson RF, Wenzel RP (1988) Hospital-acquired candidemia. The attributable mortality and excess length of stay. Arch Intern Med 148:2642–2645

Rex JH, Walsh TJ, Sobel JD, Filler SG, Pappas PG, Dismukes WE et al (2000) Practice guidelines for the treatment of candidiasis. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 30:662–678

Pappas PG, Rex JH, Sobel JD, Filler SG, Dismukes WE, Walsh TJ, Edwards JE (2004) Guidelines for treatment of candidiasis. Clin Infect Dis 38:161–189

Kullberg BJ, Sobel JD, Ruhnke M et al (2005) Voriconazole versus a regimen of amphotericin B followed by fluconazole for candidaemia in non-neutropenic patients: a randomised non-inferiority trial. Lancet 366:1435–1442

Mora-Duarte J, Betts R, Rotstein C, Colombo AL et al (2002) Comparison of caspofungin and amphotericin B for invasive candidiasis. N Engl J Med 347:2020–2029

Ascioglu S, Rex JH, de Pauw B, Bennett JE, Bille J, Crokaert F et al (2002) Defining opportunistic invasive fungal infections in immunocompromised patients with cancer and hematopoietic stem cell transplants: an international consensus. Clin Infect Dis 34:7–14

Edmond MB, Wallace SE, McClish DK, Pfaller MA, Jones RN, Wenzel RP (1999) Nosocomial bloodstream infections in United States hospitals: a three-year analysis. Clin Infect Dis 29:239–244

Wisplinghoff H, Bischoff T, Tallent SM, Seifert H, Wenzel RP, Edmond MB (2004) Nosocomial bloodstream infections in US hospitals: analysis of 24,179 cases from a prospective nationwide surveillance study. Clin Infect Dis 39:309–317

Patel M, Kunz DF, Trivedi VM, Jones MG, Moser SA, Baddley JW (2005) Initial management of candidemia at an academic medical center: evaluation of the IDSA guidelines. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 52:29–34

Reboli ARC, Pappas P et al (2005) Anidulafungin vs. fluconazole for treatment of candidemia and invasive candidiasis. In: Programs Abstr 45th Interscience Conf Antimicrobial Agents Chemotherapy. Washington D.C.

Pfizer (2006) Eraxis (anidulafungin) for injection. http://www.pfizer.com/pfizer/download/uspi_eraxis.pdf

Ruhnke MAKE, Chetchotisakd P et al (2005) Comparison of micafungin and liposomal amphotericin B for invasive candidiasis. In: Programs Abstr 45th Interscience Conf Antimicrobial Agents Chemotherapy. Washington D.C.

Gudlaugsson O, Gillespie S, Lee K, Vande Berg J, Hu J, Messer S, et al (2003) Attributable mortality of nosocomial candidemia, revisited. Clin Infect Dis 37:1172–1177

Zaoutis TE, Argon J, Chu J, Berlin JA, Walsh TJ, Feudtner C (2005) The epidemiology and attributable outcomes of candidemia in adults and children hospitalized in the United States: a propensity analysis. Clin Infect Dis 41:1232–1239

Acknowledgments

This project would not be possible without the support and guidance provided by Axiom Real-Time Metrics, Inc. and The Synapse Group, Ltd. The authors would like to thank Dr. Chi-Hsing Chang for the statistical analysis and gratefully acknowledge Karen Webster and Sue Elliott for their significant contribution in completing this project.

Financial support

Astellas provided assistance with the study design and statistical analysis.

Potential conflict of interest

D.H. has received grant support (research) from Astellas and Pfizer, has been a consultant for Astellas and on the speakers’ bureau for Astellas and Pfizer.

D.N. has received grant support (research) from Astellas.

J.F. has been a consultant to Gilead, Merck Inc., FDA/CBER-Xenotransplantation, Biogen-IDEC, Hoffman LaRoche, Athelas, ViroPharma, Astellas, Primera, is a member of the DSMB for Immune Tolerance Network-NIAID-NIH Transplantation Trials, has received grant support (educational/research) by Astellas, and has been on the speakers’ bureau for Astellas, Roche, Pfizer, and Gilead.

W.S. has served as consultant to Pfizer, Astellas, and Schering-Plough.

E.A. has been a consultant to and on the speakers’ bureau for Astellas, Pfizer, Gilead, Merck, and Schering-Plough.

K.A.M. has been a consultant to Pfizer, Merck, Enzon, Astellas, and Schering-Plough.

M.P. has been a consultant to and on the speakers’ bureau for Pfizer, Astellas, Merck, and Schering-Plough.

A.O. has been on the speakers’ bureau for Pfizer.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Horn, D., Neofytos, D., Fishman, J. et al. Use of the PATH Alliance database to measure adherence to IDSA guidelines for the therapy of candidemia. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 26, 907–914 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-007-0383-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-007-0383-4