Abstract

To improve interfacial adhesion between wood veneer and high-density polyethylene (HDPE) film, wood veneer was thermally modified in an oven or chemically modified by vinyltrimethoxysilane. The wood veneers were used to prepare plastic-bonded wood composites (PBWC) in a flat-press process using HDPE films as adhesives. The results showed that both modifications reduced veneer hydrophilicity and led to enhancement in shear strength, wood failure, and water resistance of the resulting PBWC. The thermal treatment significantly decreased the storage modulus close to 130 °C (the melting temperature of plastic). Thermal-treated wood veneer maintains mechanical interlocking for bonding and veneer strength which then declined under thermal treatment due to hemicellulose degradation and cellulose de-polymerization. In the silane-treated PBWC, enhanced interlocking and a stronger bonding structure resulted from the reaction between the silane-treated veneer and HDPE. This strong bonding structure allowed thermal stability improvement demonstrated by high modulus and low tanδ values. However, the strength of silane-treated PBWC was still much lower than thermosetting resin-bonded composites at higher temperatures due to the melting behavior of thermoplastic polymer, precluding its use in certain applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Wood-based panels have long been used as alternative to solid wood in a variety of applications, such as housing construction and furniture manufacturing. However, formaldehyde emission is a growing concern associated with petroleum-based phenol–formaldehyde (PF) or urea–formaldehyde (UF) resin-bonded wood products, forcing the wood industry to develop alternative environmentally friendly wood adhesives and new bonding methods [1–3].

Recently, plastic film has been developed as a new generation, formaldehyde-free adhesive for wood composites, since it is inexpensive, relatively tough, and shows good dimensional stability when exposed to moisture [4, 5]. Compared with the conventional UF-bonded wood composites, plastic-bonded wood composites (PBWC) offer several advantages, such as relatively simple processing technology, improved water resistance, and, most importantly, environmentally safe. Compared with wood-plastic composites manufactured by extrusion or injection molding, flat-pressed PBWC allow higher wood loading with a variation of plastics providing significantly improved performance at lower density and cost. In addition, this method allows the production of larger sized products at lower pressure [6, 7]. PBWC are increasingly being utilized in some commodity and nonstructural applications, such as floors and automobile interior components.

However, these materials lose strength dramatically after being soaked in boiling water, which prevents their usage for outdoor and construction-related applications. This is due to the incompatibility of the hydrophilic wood with hydrophobic plastic materials, especially polyolefin plastic, such as polypropylene (PP) and polyethylene (PE) [8, 9]. This incompatibility can cause insufficient wetting of the plastic on the surface of wood which leads to weak interfacial adhesion between the two phases. In addition, due to the melting behavior of the thermoplastic polymer, PBWC strength is lost at higher temperatures especially when the temperatures approach the melting point of the plastic.

Numerous modification methods have been tested to counter the incompatibility between hydrophilic wood and hydrophobic thermoplastic, including the surface functionalization of wood [10–14] or addition of coupling agents [15–19]. Tran et al. [20] investigated surface treatments of rice and wheat husks and husk-reinforced poly lactic acid (PLA) bio-composites with alkaline or one of two kinds of organosilanes [γ-aminopropyltriethoxysilane (APS) and γ-glycidoxypropyltrimethoxysilane (GPS)]. They found that husks/PLA bio-composites with husks treated with alkaline (5 % for 24 h) followed by silane surface treatment had higher mechanical properties and thermal stability. Church et al. [21] demonstrated that the interfacial properties of cellulose-based bio-composites can be altered by the surface deposition and adsorption of polyethylene glycol (PEG)-based amphiphilic block copolymers using a greener alternative methodology. Improvements in flexural modulus of up to 54 and 115 % were observed for PLA- or high-density polyethylene (HDPE)-based bio-composites. Li [22] reported that fiber acetylation increased the surface free energy of eucalyptus wood fibers from 24.7 to 38.3 mJ m−2, higher than PP (29.4 mJ m−2). The acetylation facilitates the spreading of PP on the surface of wood fibers, allowing good interfacial adhesion between the acetylated eucalyptus wood fibers and PP. Liu et al. [23] introduced organo-montmorillonite (OMMT) to wood flour to form high-performance composites. This modification and its application with PLA composites showed reduced water swelling in both the modified wood flour and the resulting composites, and also improved flexural properties at a suitable OMMT loading.

However, most previous work focused on wood fiber or wood powder. Since both wood fiber (powder) and wood veneer have reactive hydroxyl groups, there is significant interest in the application of these methods for the improvement of wood veneer. Previous work showed increased compatibility between wood veneer and plastic film by spraying silane agent on veneers [24, 25], but this chemical-based method was limited in its industrial use because of high modification costs and relatively complicated processing. Thus, there is an urgent need to develop other methods.

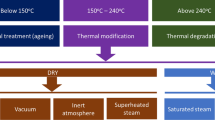

Thermal treatment is another relatively benign modification method that is being explored as a strategy to improve the compatibility of wood and hydrophobic thermoplastic without contaminating the environment. To date, there are reports of improved dimensional stability, water resistance, and biological resistance, but no improvement of mechanical properties, including strength, has been reported [26–28]. Since there may be advantages and disadvantages of the chemical and thermal approaches, it is necessary to compare these processes side-by-side. To the best of authors’ knowledge, such a comparison of the two methods has not been reported in the literature, and thus, there is little evidence to indicate either method is better than the other for the improvement of interfacial adhesion between wood veneer and plastic film. Here, poplar veneers were either thermally treated in the oven or sprayed by silane agents before being composited with HDPE films. We investigated the effect of these treatment methods on veneer surface properties and the physical–mechanical performance of the resulting panels. Our results will guide further efforts to prepare cost-effective and high-performance non-formaldehyde panels.

Materials and methods

Materials

Rotary poplar veneers measuring 300 × 300 × 1.6 mm were purchased from Zuo Gezhuang (Hebei, China). All the veneers before modified and pressed were stored at 25 °C under 45 % relative humidity (RH) to reach an approximate equilibrium moisture content of 8 %. HDPE film was provided by Environment-Protecting Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) and had a thickness of 0.06 mm and a density of 0.92 g cm−3. Silane A-171 (vinyltrimethoxysilane) was provided by Guangzhou Zhongjie Chemical Technology Co., Ltd and dicumyl peroxide (DCP) was purchased from JK Chemical and used as surface modifier for poplar veneers.

Veneer surface modification

Poplar veneers (T0) were modified either by the physical method or by chemical method. For physical modification (T1), veneers were exposed to 200 °C in an oven for 30 min. For the chemical method (T2), veneers were sprayed with silane solutions composed of ethanol/de-ionized water (9:1 by volume) with a 2 % silane (weight percent compared to the veneers) and a small fraction of DCP (0.05 % of the HDPE dosage) until the silane solution concentration reached 4 % at a pH value of 3–3.5. After spraying the silane solution, veneer samples were air-dried for at least 24 h and finally treated at 120 °C in the convection oven for 2 h.

Veneer characterization

Contact angles (CA)

Wood veneers were cut into small strips of 70 × 10 × 1.5 mm (Longitudinal × Tangential × Radial), and the CA of the wood veneers were measured with OCA 20 (Data Physics Instruments, Germany) using distilled water. Room temperature and RH were controlled at 25 °C and 50 %, respectively. Ten repetitions were tested with three drops for each sample. The average contact angles gained after 5 s from the time, the water droplet was dropped on the surface, were compared.

Dynamic vapor sorption (DVS)

Isotherm analyses were performed using dynamic vapor sorption apparatus ((DVS Intrinsic, Surface Measurement System Ltd., London, United Kingdom). The schedule for the DVS was set to ten different RH values: 0, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80, and 90 %. The temperature was constant 25 °C during the entire experiment. The DVS is designed to accurately measure the change in mass of a sample, as it sorbs precisely controlled concentrations of water vapors in nitrogen carrier gas. At each RH, an algorithm was used to ensure that equilibrium had been reached when the slope of an adjusted tangent line was <0.002 % min−1 relative to the curve of mass change with respect to time for the last 10 min of data collection. Data on mass change were acquired every 60 s. Three sorption cycles were run for each veneer sample.

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS)

The XPS spectra of the untreated and treated veneers were recorded on a Thermo ESCALAB 250 Xi spectrometer using Al Kα (hv = 1486.6 eV) at 150 W. Binding energies were calibrated with C1s of 284.8 eV, and the analysis of the spectra was performed using the commercial curve-fitting software. Three replicates were used for each veneer.

PBWC manufacturing and testing

Five-layer laboratory PBWC panels of dimension 300 × 300 × 8 mm were first assembled with one piece of HDPE film between every two veneers (treated or untreated). The panels were prepared with opposing tight-side and loose-side veneers in all the glue lines, and were stacked with the grain directions of the two adjacent veneers perpendicular to each other. PBWC panels were hot-pressed at 1 MPa pressure and 160 °C for 8 min followed by a cold-press stage at 1 MPa performed at room temperature for 5 min, which was used to reduce the distortion and stress of the panel. At the same time, sandwich specimens (two-layer PBWC with one piece of HDPE film between two parallel veneers) were also prepared at 1 MPa pressure and 160 °C for 3 min followed by a cold-press stage performed at room temperature for 5 min, for dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA) and scanning electron microscope (SEM) observation.

Water absorption (immersion in water at 20 °C for 24 h), shear strength (immersion in boiling water for 4 h, then drying at 63 ± 3 °C in the drying oven for 20 h, then immersion in boiling water for 4 h), wood failure, and three-point bending strength, including modulus of rupture (MOR) and modulus of elasticity (MOE), were evaluated according to Chinese National Standard GB/T 17657-2013 [29]. Mechanical properties were measured using a Multi-Function Mechanical Testing machine (Jinan Shijin Co.Ltd, 10 kN), with a crosshead speed of 5 mm min−1. Eighteen specimens (100 × 25 mm) for the shear strength test, fifteen specimens (220 × 50 mm) for the measurement of MOR and MOE, and twelve specimens (100 × 100 mm) for the water absorption (WA) test were cut from three replicate panels, respectively. Before testing, all samples were conditioned at 25 °C and 65 % RH for 1 week.

DMA

DMA measurements were conducted of the sandwich specimens of about 60 × 12 × 3.2 mm (Longitudinal × Tangential × Radial) in three-point bending mode at a span of 50 mm on a TA Instruments Q2980 with a frequency of 1 Hz and constant amplitude of 0.03 mm. Temperature ramp experiments were performed at a heating rate of 3 °C min−1 from room temperature to 200 °C with triplicates.

SEM

The interface morphology of the sandwich specimens of about 10 × 10 mm (length × width) was assessed by coating with gold and examination using an S-4800 scanning electron microscope at different magnification factors.

Results and discussions

Characterization of surface modified veneers

The surface chemistry and wettability of different veneer samples were evaluated using XPS, CA, and DVS.

XPS

XPS allows the determination of surface composition and the chemical environment for different veneers. Figure 1 shows the electron intensity as a function of binding energy for untreated (T0), thermal-treated (T1), and silane-treated (T2) poplar veneers, and the specific values are presented in Table 1. As expected, O1s and C1s occur at 533 and 285 eV, respectively, and are the predominant species for lignocellulosic material [30, 31]. The T0 and T1 veneers show similar XPS spectra as expected based on their equivalent chemical composition. However, “T1 veneers show a relative increase in carbon content and a relative reduction in oxygen content when compared to the data of T0 veneer.” The slight decrease in the O/C ratio is likely due to hemicellulose decomposition and lignin plasticization leading to a reorganization of lignocellulosic polymeric components of wood. For T2 veneers, an increased O/C ratio and the presence of silicon (2.2 % presented in Table 1) indicated that prehydrolyzed silane deposited on the veneer allowing interactions of Si–OH bonds with hydroxyl groups on the veneer surface. Condensation reaction between silane and wood veneer also took place, which can be detected from the characteristic emission peaks in the region between 150 and 155 eV for Si2s and 99 and 104 eV for Si2p, as shown in the insert of Fig. 1.

In Table 1, the values of emission peaks for carbon atoms in the different veneer samples are also presented. All three samples showed at least two different emission peaks, indicating the presence of more than one compound on the veneer surface. Nevertheless, the deconvolution of the peak corresponding to carbon atoms in the XPS spectrum for T1 and T2 veneers revealed a major difference related to the C1 peak at 284 eV when compared to the pattern of untreated samples; an increase from 57.50 % to 59.28 and 74.2 %, respectively. This is likely because the two treating methods eliminated carbohydrate from the wood veneer and thus decreased the veneer polarity. This effect was more pronounced for the T2 veneers, as indicated by the presence of a new C3 peak at 288 eV representing the emission of C–O–Si bond on the veneer surface, which further confirmed the presence of the silane group deposited on the surface and able to react with the wood veneers.

DVS

DVS apparatus is a relatively new technique developed to collect continuous weight change over time at any desired RH value between 0 and 95 % within a short period of time. As shown in Fig. 2, the adsorption/desorption properties of different wood veneers exhibited classic Type II sigmoidal isotherms. However, there were considerable differences in the total amount of moisture in the samples at a given RH, and the T1 sample showed the lowest hygroscopicity. For example, at a target RH of 90 %, the unmodified wood veneer exhibited the highest EMCs (15.36 %), followed by T2 veneer (14.71 %) and T1 veneer (13.3 %).

Adsorption of water was thought to depend on OH groups on the wood veneer surface. It can be studied by evaluating the quantity and the state of the OH groups, which acted as the adsorption sites according to Hailwood–Horrobin (HH) model [32]. Based on the HH model [33], molecular weight per sorption site for T0, T1, and T2 veneers were calculated, that was 308.74, 484.28, and 349.36, respectively. The reduced sorption capacity of treated veneers was a consequence of the conversion of OH groups to less hydrophilic groups.

In the HH model, monolayer water that was H-bonded to the cell wall polymeric OH groups can change over the whole range of RH and is thus a much more appropriate description for an evolving surface associated with a material that changes dimension as sorption proceeds [34]. Therefore, the accessible OH content of the three kinds of veneer was determined by each water molecule in the monolayer, which is shown in the insert graph of Fig. 2. Veneers after thermal-treated at 200 °C presented the lowest OH concentrations of 1.56 m moles g−1, 40 % less than the untreated sample. It should be noted that the value of OH concentration cannot be accurately controlled, and was only used for comparison.

CA

The effect of the modification methods on the wettability measured on different wood surfaces is shown in Fig. 3. The two treatments altered the naturally hydrophilic poplar veneer to become rather hydrophobic, making it easier to be wetted by melted plastic films. Both T1 and T2 veneers showed a higher average contact angle than the control samples, as average contact angles increased from 28° for untreated veneers up to 119° for the thermally modified and 97° for the silane-treated samples. In addition, the contact angles of the untreated veneers decreased approximately to zero degree within 20 s but changed only several degrees from the time of dropping a water droplet on the surface to its time of stabilization for both the T1 and T2 surfaces. This behavior was expected, because the thermal treatment reduced the interaction of wood with many liquids, including water, and the silane agent interacted with the hydroxyl on the veneer surface.

Taken together, these findings indicate that both methods can decrease the hygroscopicity of poplar veneers and thus improve the interfacial compatibility between wood veneers and plastic film. Thermal treatment is better able to reduce the polarity of wood veneers, while chemical reaction allowed silane modifications.

Physical–mechanical properties

The mean values of shear strength, wood failure, MOR, MOE, and WA of PBWC are summarized in Table 1. Both surface modifications showed a highly positive effect on shear strength and wood failure (Fig. 4). The shear strength of untreated panel was only 0.44 MPa, much lower than the requirement for Type I grade plywood of GB/T 9846.3-2004 [35]. In addition, its wood failure value was less than 5 %. The highest shear strength values for PBWC were obtained with 2 % silane A-171, an increase of 330 % in comparison with the non-treated panels due to the chemical reaction between silane-treated veneers and HDPE radicals generated by the dicumyl peroxide at an elevated temperature during hot-pressing (Fig. 5). The mechanical properties of thermal-treated PBWC were relatively low, probably because HDPE film could only interact with the wood veneers by enhanced mechanical interlocking rather than chemical bonding.

T1 and T2 PBWC both showed improved water resistance. WA value decreased by 28 and 32 % for T1 and T2 PBWC, respectively, when compared to the untreated sample. However, MOR and MOE values of the specimens were adversely influenced by the surface treatments, especially the thermal treatment. Thermal-treated PBWC had 28 and 21 % lower MOR and MOE values, respectively, than those of control samples. This could be related to the oxidation reaction and higher hemicellulose degradation in the wood that reduced the strength of the wood veneer. The weight loss under the condition of thermal modification reached 9.7 %.

Of the two methods considered in this work, thermal treatment is more suitable for improving dimensional stability because of the resulting decreased polarity of wood veneers, while silane treatment is more effective in increasing interface adhesion and thus shear strength and wood failure, which may be due to the strong bond formed between the organo-functional group of the silane-treated veneer and vinyl radicals of HDPE generated by the dicumyl peroxide.

DMA

The storage modulus and typical loss factor (tanδ) of PBWC with respect to temperature are shown in Fig. 6a and b, and Table 1. Over the range of temperatures investigated, silane-treated PBWC exhibited the best thermal stability, especially in the range of 120–140 °C. A sharp decrease (43 %) in storage modulus for untreated PBWC near 130 °C was observed, which may be due to the melting behavior of HDPE film. At this stage, the bondline in the PBWC began to slip and the mechanical interlock formed in the wood veneer gradually weakened. In the case of silane treatment, dominant interfacial bonding mechanism between wood veneer and HDPE film changed from mechanical interlocking to chemical bonding. This allowed only a 15 % decrease in storage modulus when the temperature rose to 130 °C, compared to a much more significant decrease in storage modulus (66 %) for the thermally treated sample, although there was a reduction in veneer polarity and better adhesive bonding. This may be attributed to the formation of soluble acidic chemical from hemicellulose degradation that accelerated the de-polymerization of the celluloses.

As expected, the silane treatment resulted in a more rigid interface showing the lowest tanδ value (0.06) at 130 °C and the highest temperature (180 °C) arriving at tanδ peak value. Low tanδ value near the melted point of HDPE for silane-treated PBWC corresponded to better wood/plastic adhesion and compatibility. However, their practical value would be still lost at much higher temperature. For example, modulus retention rate for silane-treated PBWC was less than 40 % at 200 °C. The case was completely different for thermosetting resin-bonded composites. Take UF resins, for example, decrease of storage modulus was less than 5 % in the whole stage. This is because thermosetting polymer would never melt or soften again once cured [6]. A tiny part of decreased modulus was caused by the decomposition of UF bondline at high temperature.

SEM

In Fig. 7a, it can be seen that melted HDPE flowed and penetrated into the vessels of wood veneer, forming a continuous bondline and mechanical interlock structure. However, there were wide gaps on the interface, indicating poor interfacial adhesion. This weak interface as well as the interlock can be seen more clearly in Fig. 7b. Weak interfacial adhesion allowed the debonding of the HDPE adhesive from the wood veneer, and thus, the shear strength after soaking in the boiling water was extremely low.

Although the compatibility of the wood veneer and HDPE film was improved under thermal treatment, this is by increasing the ability of HDPE molecules to fill the small cavities on the veneer to form mechanical interlock. The bonding interface remained poor as reflected in the gap on the interface in Fig. 7c and the relatively low mechanical properties. Enhanced interlock and a stronger wood/plastic interface were observed in the silane-treated PBWC sample (Fig. 7d). This clearly demonstrated that silane A-171 successfully improved interfacial adhesion by tethering one end to the veneer surface allowing the functionality at the other end to react with the HDPE in the presence of peroxide initiators, which should increase the mechanical properties of the composites, as shown in Table 1.

Conclusions

In the present work, we studied the effects of two veneer surface treatments on the physical–mechanical and interfacial properties of the resulting PBWC. In general, both methods reduced the hydrophilicity of poplar veneers and the PBWC showed increased shear strength and water resistance. Chemical reaction was only observed in the silane treatment. Due to the strong bond formed between the organo-functional group of the silane-treated veneer and vinyl radicals of HDPE generated by the dicumyl peroxide, silane-treated PBWC possesses the best bonding structure as reflected by the highest shear strength, wood failure, and thermal stability compared to the heat-treated PBWC. Thermal treatment reduces the polarity of wood veneers, and thermal-treated PBWC showed the lowest MOR and MOE value as well as modulus retention rate due to hemicellulose degradation and celluloses de-polymerization.

Although the two treated PBWC both meet the requirement for Type I grade plywood of GB/T 9846.3-2004 [35], they are not able to totally replace the traditional thermosetting resin-bonded composites because of their low strength at high temperature. The two methods cannot change the melting characteristics of plastic, and thus, it is necessary to use new plastic types or modify the plastic in some way to broaden the application of these materials.

References

Demirkir C, Colak S, Aydin I (2013) Some technological properties of wood–styrofoam composite panels. Compos B Eng 55:513–517

Moubarik A, Pizzi A, Allal A, Charrier F, Charrier B (2009) Cornstarch and tannin in phenol–formaldehyde resins for plywood production. Ind Crop Prod 30:188–193

Cheng HN, Dowd MK, He Z (2013) Investigation of modified cottonseed protein adhesives for wood composites. Ind Crop Prod 46:399–403

Wang Z, Guo WJ (2001) Production technical of environmental-friendly plywood. Patent, CN 1292320 A

Fang L, Chang L, Guo WJ, Chen YP, Wang Z (2013) Manufacture of environmentally friendly plywood bonded with plastic film. Forest Prod J 63:283–287

Fang L, Chang L, Guo WJ, Ren YP, Wang Z (2013) Preparation and characterization of wood-plastic plywood bonded with high density polyethylene film. Holz Roh Werkst 71:739–746

Wang Z, Guo WJ, Gao L (2005) Properties, applications and development trends of wood-plastic composite particleboard. China Wood-Based Panels 5:12–15

Xie YJ, Hill CAS, Xiao ZF, Militz H, Mai C (2010) Silane coupling agents used for natural fiber/polymer composites: a review. Compos Part A-Appl S 41:806–819

Tang L, Zhang ZG, Qi J, Zhao JR, Feng Y (2011) The preparation and application of a new formaldehyde-free adhesive for plywood. Int J Adhes Adhes 31:507–512

Zhang H (2014) Effect of a novel coupling agent, alkyl ketene dimer, on the mechanical properties of wood–plastic composites. Mater Design 59:130–134

Zhang HH, Cui Y, Zhang Z (2013) Chemical treatment of wood fiber and its reinforced unsaturated polyester composites. J Vinyl Addit Techn 19:18–24

Goriparthi BK, Suman KNS, Rao NM, Goriparthi BK, Suman KNS, Rao NM (2012) Effect of fiber surface treatments on mechanical and abrasive wear performance of polylactide/jute composites. Compos Part A-Appl S 43:1800–1808

Dányádi L, Móczó J, Pukánszky B (2010) Effect of various surface modifications of wood flour on the properties of pp/wood composites. Compos Part A-Appl S 41:199–206

Wei LQ, Mcdonald AG, Freitag C, Morrell JJ (2013) Effects of wood fiber esterification on properties, weatherability and biodurability of wood plastic composites. Polym Degrad Stabil 98:1348–1361

González-Sánchez C, Martínez-Aguirre A, Orden MUDL, Fonseca-Valero C (2014) Use of residual agricultural plastics and cellulose fibers for obtaining sustainable eco-composites prevents waste generation. J Clean Prod 83:228–237

Ifuku S, Yano H (2015) Effect of a silane coupling agent on the mechanical properties of a microfibrillated cellulose composite. Int J Biol Macromol 74:428–432

Xu KM, Li KF, Zhong TH, Guan LT, Xie CP, Li S (2014) Effects of chitosan as biopolymer coupling agent on the thermal and rheological properties of polyvinyl chloride/wood flour composites. Compos B Eng 58:392–399

Hong HQ, Liao HY, Zhang HY, He H, Liu T, Jia D (2014) Significant improvement in performance of recycled polyethylene/wood flour composites by synergistic compatibilization at multi-scale interfaces. Compos Part A-Appl S 64:90–98

Faludi G, Dora G, Renner K, Móczó J, Pukánszky B (2013) Improving interfacial adhesion in pla/wood biocomposites. Compos Sci Technol 89:77–82

Tran TPT, Bénézet JC, Bergeret A (2014) Rice and einkorn wheat husks reinforced poly (lactic acid) (pla) biocomposites: effects of alkaline and silane surface treatments of husks. Ind Crop Prod 58:111–124

Church JS, Voda AS, Sutti A, George J, Fox BL, Magniez K (2015) A simple and effective method to ameliorate the interfacial properties of cellulosic fibre based bio-composites using poly (ethylene glycol) based amphiphiles. Eur Polym J 64:70–78

Li Y (2014) Characterization of acetylated eucalyptus wood fibers and its effect on the interface of eucalyptus wood/polypropylene composites. Int J Adhes Adhes 50:96–101

Liu R, Luo SP, Cao JZ, Peng Y (2010) Characterization of organo-montmorillonite (OMMT) modified wood flour and properties of its composites with poly(lactic acid). Compos Part A-Appl S 51:33–42

Fang L, Chang L, Guo WJ, Chen YP, Wang Z (2014) Influence of silane surface modification of veneer on interfacial adhesion of wood-plastic plywood. Appl Surf Sci 288:682–689

Fang L, Wang Z, Xiong XQ, Wang XH, Wu ZH (2016) Effects of initiator on properties of silane modified poplar veneer/high density polyethylene (HDPE) film composites. J Nanjing For Univ (Natural Sciences Edition) 40:133–136

Follrich J, Müller U, Gindl W (2006) Effects of thermal modification on the adhesion between spruce wood (Picea abies Karst.) and a thermoplastic polymer. Holz Roh Werkst 64:373–376

Ayrilmis N, Jarusombuti S, Fueangvivat V, Bauchongkol P (2011) Effect of thermal-treatment of wood fibres on properties of flat-pressed wood plastic composites. Polym Degrad Stabil 96:818–822

Kaboorani A, Faezipour M, Ebrahimi G (2008) Feasibility of using heat treated wood in wood/thermoplastic composites. J Reinf Plast Comp 27:1689–1699

GB/T 17657-2013 (2014) Test methods of evaluating the properties of wood-based panels and surface decorated wood-based panels. Chinese National Committee for standardization, Beijing, PR China, pp 27–29

Valadez-Gonzalez A, Cervantes-Uc JM, Olayo R, Herrera-Franco PJ (1999) Chemical modification of henequén fibers with an organosilane coupling agent. Compos B Eng 30:321–331

Abdelmouleh M, Boufi S, Salah AB, Belgacem MN, Gandini A (2002) Interaction of silane coupling agents with cellulose. Langmuir 18:3203–3208

Hill CAS, Norton A, Newman G (2009) The vapor sorption behavior of natural fibers. J Appl Polym Sci 112:1524–1537

Zaihan J, Hill CAS, Curling S, Hashim WS, Hamdan H (2009) Moisture adsorption isotherms of acacia mangium and endospermum malaccense using dynamic vapour sorption. J Trop For Sci 21:277–285

Hailwood AJ, Horrobin S (1946) Absorption of water by polymer analysis in terms of a simple model. Trans Faraday Soc 42:84–102

GB/T 9846.3-2004 (2004) General specification for plywood for general use. Chinese National Committee for standardization, Beijing, PR China, p 14

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This study was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (CN) (No. BK20150881), the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (PAPD), Innovation Fund for Young Scholars of Nanjing forestry University, China (No. CX2015020), and the Starting Foundation of Nanjing forestry University, China (No. GXL024).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

About this article

Cite this article

Fang, L., Xiong, X., Wang, X. et al. Effects of surface modification methods on mechanical and interfacial properties of high-density polyethylene-bonded wood veneer composites. J Wood Sci 63, 65–73 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10086-016-1589-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10086-016-1589-9