Abstract

Children’s mental health is deteriorating while access to child and adolescent mental health services is decreasing. Recent UK policy has focused on schools as a setting for the provision of mental health services, and counselling is the most common type of school-based mental health provision. This study examined the longer-term effectiveness of one-to-one school-based counselling delivered to children in UK primary schools. Data were drawn from a sample of children who received school-based counselling in the UK in the 2015/16 academic year, delivered by a national charitable organisation. Mental health was assessed at baseline, immediately post-intervention, and approximately 1 year post-intervention, using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) completed by teachers and parents. Paired t tests compared post-intervention and follow-up SDQ total difficulties scores with baseline values. Propensity score matching was then used to identify a comparator group of children from a national population survey, and linear mixed effects models compared trajectories of SDQ scores in the two groups. In the intervention group, teacher and parent SDQ total difficulties scores were lower at post-intervention and longer-term follow-up compared to baseline (teacher: baseline 14.42 (SD 7.18); post-intervention 11.09 (6.93), t(739) = 13.78, p < 0.001; follow-up 11.27 (7.27), t(739) = 11.92, p < 0.001; parent: baseline 15.64 (6.49); post-intervention 11.90 (6.78), t(361 = 11.29, p < 0.001); follow-up 11.32 (7.19), t(361) = 11.29, p < 0.001). The reduction in SDQ scores was greater in the intervention compared to the comparator group (likelihood ratio test comparing models with time only versus time plus group-by-time interaction: χ2 (3) = 24.09, p < 0.001), and model-predicted SDQ scores were lower in the intervention than comparator group for 2 years post-baseline. A one-to-one counselling intervention delivered to children in UK primary schools predicted improvements in mental health that were maintained over a 2 year follow-up period.

Similar content being viewed by others

Approximately half of adults with mental health disorders experienced their initial symptoms before the age of 14 [1, 2], and there is now convincing evidence that the mental health of children is in decline [3, 4]. Access to child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS) is decreasing as services struggle with increasing referrals and fewer resources [5, 6], and the COVID-19 pandemic is accelerating mental health changes in adults, particularly emerging adults, with children and young people predicted to be even more vulnerable [7,8,9]. Increased access to effective mental health intervention for children and adolescents should be a critical priority to prevent entrenchment of poor mental health into adolescence and early adulthood, but it is unlikely that CAMHS can expand sufficiently rapidly to meet this increased need.

Recent UK policy has focused on increasing the liaison between CAMHS and schools with the training of school-based mental health practitioners [10]. Schools provide an optimal setting for the provision of early-intervention mental health services given their near-universal access to children and families, including those considered hard-to-reach. Children who are well educated have better health and wellbeing, while those with better health, including better mental health, perform better at school [11]. Children with mental health problems have poorer academic attainment, greater school absences, and an increased risk of school exclusion compared to their mentally healthy peers [12,13,14]. Recent research by the Institute for Public Policy Research showed that parents would like greater priority to be given to school-based mental health support, while more than 70% of teachers believed greater access to onsite mental health support would improve student attainment [15].

Counselling is the most common type of school-based mental health provision and is currently offered in 60–70% of schools in England, although it is less likely to be available in primary compared to secondary schools [15,16,17]. Previous studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of school-based counselling at improving mental health post-intervention and for up to 3 months afterwards [18,19,20]. However, less is known about the longer-term impact of school-based counselling. A previous pilot study evaluated the effectiveness of school-based humanistic counselling delivered to 64 adolescents aged 11 to 18 years, and found that the benefits observed immediately post-intervention were not sustained at 6 or 9 month follow-up [21]. However, research has yet to examine the longer-term effectiveness of school-based counselling delivered to primary school children.

Place2Be is a mental health charity that provides mental health support, including one-to-one counselling, to children in schools across the UK. Previous research has demonstrated that this counselling intervention has a positive short-term impact on the mental health of primary school children [20], and also has economic benefits resulting from higher employment output and lower spending on public services, amounting to over £5700 per child [22]. However, the longer-term effectiveness of the counselling intervention on children’s mental health has yet to be explored.

The current study aims to examine the longer-term effectiveness of this school-based counselling intervention by addressing the following research questions:

-

1.

Does the school-based counselling intervention lead to improvements in primary school children’s mental health measured (a) immediately after counselling is completed, and (b) approximately 1 year later?

-

2.

How do the mental health trajectories of children who receive the counselling intervention compare to the trajectories of a matched group of children who did not receive a mental health intervention?

Methods

Participants

Intervention group

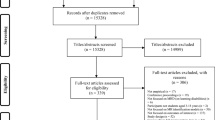

Data were drawn from 2612 primary school children who received the counselling intervention during the 2015/16 academic year. Follow-up assessments were carried out with the 1149 children who were in school years 1 to 5 (to reduce administrative burden associated with tracing children into secondary school), did not receive another intervention during the follow-up period, and had baseline and post-intervention Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaires (SDQs) available. Children were excluded from the follow-up analysis presented here if they had left the school or the school left the counselling service. This resulted in 826 and 612 children eligible for inclusion in the teacher and parent reported follow-up analysis, respectively, of which 740 (89.6%) and 362 (59.2%) provided follow-up data (see Fig. 1).

Comparator group

The 2004 British Child and Adolescent Mental Health Survey (BCAMHS) was a nationally representative population survey of young people in Great Britain aged 5 to 16 years, sampled via the Child Benefit register, which at that time was a universal benefit available to all parents. Four hundred and twenty-six postal sectors were randomly sampled by the Office for National Statistics, stratified by regional health authority and socio-economic group. A total of 10496 families were approached and 7977 completed a baseline interview. Full details of the survey methods are reported by Green and colleagues [23]. To identify a comparison sample of children for the current analysis, we excluded children who had been in contact with specialist mental health or education services in relation to the child’s mental health (n = 450). Of the remaining 7527 children, 6584 had an SDQ at baseline and at least one follow-up period, and were included into the pool for matching with the intervention group.

Procedure

Intervention group

Referral pathways into the counselling service varied, but children were most commonly referred by school staff (see Tables S4 and S5 in online supplementary information). Initial assessments were undertaken by school-based counsellors with the child, their parent/carer, and their main class teacher to determine reasons for referral, develop a clinical formulation, and obtain demographic and clinical information, including completion of the SDQ by the parent and teacher. The intervention is based on a combination of person-centred, psychodynamic and systemic therapeutic approaches. Sessions may involve talking, creative work, and play, and take place in a room at the school equipped with toys and creative materials. Children were offered 12 to 36 weekly sessions, which typically ended through mutual agreement between the child and therapist, although treatment could also end at the request of the parent or child, or if the child left the school or was excluded. On completion of counselling, post-intervention assessments were undertaken with the child, parent and teacher to assess the child’s progress, including completion of the SDQ. Teachers and parents were asked to complete a further SDQ approximately 1 year after the post-intervention assessment.

Comparator group

In the 2004 BCAMHS, face-to-face interviews were conducted with parents of all children at baseline and 36 month follow-up, while keep-in-touch postal questionnaires were mailed to parents at 6, 12 and 24 months. The SDQ was completed at each of these time-points. A postal questionnaire, including the SDQ, was also sent to teachers at baseline and 36 months, where parents provided consent.

Measures

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ)

In both the intervention and comparator samples mental health was assessed with the SDQ, which is a validated questionnaire that screens for common psychopathology in children aged 4 to 16 years [24]. Versions are available for completion by parents, teachers and young people aged 11 years or above. Due to the young age of participants, only teacher and parent reports were used for this study. The SDQ consists of 25 items grouped into five subscales: emotional problems, conduct problems, hyperactivity-inattention, peer problems, and prosocial behaviour. A total difficulties score is calculated by summing the totals of the first four subscales; a higher score indicates greater difficulties. An impact supplement asks teachers and parents about the impact of the child’s difficulties on peer relationships and classroom learning, and additionally asks parents about the impact on home life and leisure activities. The SDQ has satisfactory internal consistency (teacher α = 0.82; parent α = 0.80), test–retest reliability (teacher r = 0.84; parent r = 0.76), and parent/teacher inter-rater agreement correlation (0.44), and is able to discriminate between clinical and community samples [25].

Background characteristics

In both samples parents were asked to report the child’s age, gender and ethnicity, as well as their highest qualification level and family structure. Teachers were asked to report whether the child had any Special Educational Needs or Disability (SEND) (referred to as Additional Support Needs in Scotland and Additional Learning Needs in Wales), which was collapsed into a binary variable in both groups (any versus no SEND). Parental mental health was assessed by asking parents whether they have a mental health problem (currently or in the last 6 months; 6 to 18 months ago; over 18 months ago; or no) in the intervention group, and via the 12-item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) in the comparison group. The GHQ-12 is a commonly used validated screening device for the identification of psychiatric disorders in the general population [26]. For the current study we created a binary parental mental health variable in both samples (GHQ-12 scores of 3 or higher in the comparison group [26], and answer “yes, currently or in the last 6 months” in the intervention group).

Analysis

Data were analysed using Stata 14 and 15 [27, 28]. Both samples were summarised using means and standard deviations for continuous variables and numbers and percentages for categorical variables. Descriptive statistics explored differences between children who did and did not have follow-up SDQs.

First, we tested whether mean teacher- and parent-reported SDQ total difficulties scores varied across time by comparing post-intervention and follow-up scores with pre-intervention values, using paired t tests on all available reports in the intervention group. Second, we used propensity score matching to identify a comparator group of children from the BCAMHS. All variables that were available in both datasets and are predictive of mental health difficulties and treatment utilisation (using previous literature and exploratory analyses with the BCAMHS data) were included as matching variables. These were: age, gender, ethnicity, family structure, baseline SDQ total difficulties and impact scores (parent- and teacher-reports), SEND status, parental qualifications, and parental mental health. Matching methods explored were: 1:1, 2:1, 3:1 and 4:1 nearest neighbour matching without replacement, caliper matching and radius matching. The model that achieved the best balance of covariates between the two groups was selected. To investigate the potential impact of residual confounding, informed by methods for sensitivity analysis suggested by VanderWeele and Arah [29], we explored the degree to which a binary unmeasured confounder would need to be associated with the intervention to move (a) the predicted difference in SDQ at 24 months to 0 and (b) the estimate of the lower confidence bound of the difference in SDQ at 24 months to 0. We explored this on a risk difference scale for the association between the binary unmeasured confounder and the treatment variable.

Once a comparator group was identified, we used linear mixed effects models (with command mixed in Stata) to identify trajectories of parent-reported SDQ total difficulties scores over time, and compared these between the intervention and comparator groups. Mixed effects models are ideal for investigating outcomes collected at repeated time-points, and benefit from being able to account for imbalanced and unstructured data (whereby individuals have data on a different number of occasions or collected at different times) [30], as well as implicitly accounting for data missing at random. This part of the analysis focused on parent reports because teacher SDQs were only collected at two time-points in the BCAMHS, and at least three data-points are required for trajectory analyses. All matching variables (described above) were included in multivariable models as level two covariates to adjust for residual confounding. Clustered standard errors were used to account for school-level clustering in the intervention group. Linear, quadratic and cubic models were tested and compared using likelihood ratio (LR) tests in a model without intervention status to describe the functional form of the time relationship. We then modelled the interaction between time and intervention status to allow estimation of treatment effect. Predictive margins with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were obtained and plotted. These represent model-predicted SDQ total difficulties scores for an average individual in the intervention and comparator groups.

Results

Sample characteristics

Table 1 summarises characteristics of the intervention and comparator groups. The mean duration of counselling was 26.0 sessions (SD 10.4), and the mean length of time between baseline and the post-intervention and longer-term follow-up assessments was 9.8 (SD 4.6) and 21.3 (SD 4.9) months, respectively. In the intervention group, there were no differences between children with missing and complete follow-up SDQ data in terms of gender, ethnicity, family structure, SEND, parental qualifications, parental mental health, receipt of pupil premium or free school meals, or care order or child protection plan (see Tables S2 and S3 in online supplementary information). Children with missing follow-up data were, however, older, had higher baseline SDQ total difficulties and impact scores, and were less likely to have been referred into the counselling service by their mother and more likely to have been referred by a learning mentor (see Tables S2 to S5 in online supplementary information). The intervention group were similar in terms of their mental health to children from the national survey who had been in contact with specialist mental health or education services in relation to their mental health (See Table S6 in online supplementary information).

Before and after counselling and follow-up comparisons

In the intervention group, mean teacher SDQ total difficulties scores reduced from 14.42 (SD 7.18) at baseline to 11.09 (6.93) post-intervention (t(739) = 13.78, p < 0.001), and this improvement was maintained at longer-term follow-up (11.27 (7.27), t(739) = 11.92, p < 0.001) (see Table 2). Likewise, mean parent SDQ total difficulties scores reduced from 15.64 (6.49) at baseline to 11.90 (6.78) post-intervention (t(361) = 11.29, p < 0.001). This improvement was also maintained at longer-term follow-up (11.32(7.19), t(361) = 11.40, p < 0.001) (see Table 2).

Trajectories of mental health in the intervention and comparator groups

The matching method that achieved the best balance of covariates was 1:1 nearest neighbour matching without replacement, which reduced imbalance overall and for each covariate individually, with the exception of parental mental health (see Figure S1 in online supplementary information). Some degree of imbalance remained in four covariates: baseline teacher SDQ total difficulties and impact score, baseline parent SDQ impact score, and parental mental health (see Table 1). These were all in the direction of marginally worse child mental health in the intervention group, and a greater proportion of parents with mental health problems in the control group. All matching variables were included as level two covariates in the linear mixed effects model.

Likelihood ratio tests suggested that a cubic functional form was more appropriate than a quadratic one (χ2 (1) = 13.02, p < 0.001). Our sensitivity analysis suggested that with an unmeasured binary confounder associated with a 1.0 SD difference in the outcome (i.e. d = 1.0 for the unmeasured confounder, which is generally regarded as a large effect), the intervention and control group would need to be unbalanced with respect to this unmeasured confounder by 84 percentage points for the true effect to equal 0; for the lower confidence interval to include unity, this imbalance would be equal to 25 percentage points. This suggests that our analysis was highly robust to unmeasured confounding.

Table 3 displays results of the final linear mixed effects model. There was no difference in baseline parent SDQ total difficulties scores between the intervention and comparator groups (adjusted coefficient: − 0.57, 95% CI − 1.58 to 0.44, p = 0.27). Across both groups SDQ scores decreased over time, and a likelihood ratio test of models with and without the group-by-time interaction terms suggested a significant effect of group on SDQ trajectories (χ2 (3) = 24.09, p < 0.001).

Figure 2 displays predicted trajectories of parent SDQ total difficulties scores (predictive margins) in the two groups across the follow-up period. The data underlying Fig. 2 can be found in Table S7 of the online supplementary information. These show that predicted SDQ scores are significantly lower in the intervention compared to the comparator group at all time-points after baseline (p < 0.001 for 3 to 21 months; p = 0.005 at 24 months). These differences represent moderate-to-large effect sizes (e.g., Cohen’s d = 0.51 at 12 months and 0.84 at 24 months; see Table S7 in online supplementary information for effect sizes at all time-points between 3 and 24 months). A similar trend was observed between 24 and 36 months, but due to a small number of children with data beyond 24 months in the intervention group, confidence intervals were wide, effect estimates imprecise, and predicted SDQ scores fell below the minimum possible score of 0. These are, therefore, not included in the main results but can be found in Table S7 of the online supplementary information.

Discussion

This study evaluated the longer-term effectiveness of a one-to-one counselling intervention delivered to children in UK primary schools. Pre- and post-intervention analyses showed improvements in children’s mental health as reported by teachers and parents at post-intervention (mean 9.8 months after baseline) and longer-term follow-up (mean 21.3 months after baseline). Trajectories of children’s mental health difficulties as reported by parents, analysed with linear mixed effects models, showed that difficulties reduced more in the intervention group than in a matched comparator group of children, and remained lower over a 2 year follow-up period. Our findings support previous research highlighting the short-term benefit of school-based counselling on children’s mental health [18,19,20], and additionally provide the first evidence to suggest that these improvements persist over a longer-term follow-up period. In addition to the strong statistical significance, the difference in SDQ scores between the intervention and control groups (model-predicted difference of 3.47 points at 12 months and 5.65 at 24 months) represents a clinically meaningful reduction in children’s difficulties. These differences translate into effect sizes of 0.51 at 12 months and 0.84 at 24 months, which would be considered moderate and large respectively, and exceed that reported at between 4 and 8 months by CAMHS in the UK (0.40) [31]. A previous economic evaluation of the same counselling intervention examined in the present paper showed clear cost benefits amounting to over £5700 per child, but this economic evaluation assumed a “fading out” of mental health benefits over time [22]. Findings from the current study suggest that these economic benefits are likely to have been under-estimated.

Our findings highlight the promising role of primary schools as a setting for the provision of intervention for childhood mental health problems, and provide support for continued calls for schools to play a role in young people’s mental health [10, 15]. This is likely to be important in the coming years given that children’s mental health is in decline and may be further adversely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, alongside increased referrals and fewer resources distributed to CAMHS [3,4,5,6,7, 9]. Counselling is the most common mental health provision currently offered in schools, but is more likely to be implemented in secondary rather than primary schools [16, 17]. Our findings suggest that greater consideration should be given to the provision of counselling in primary schools. Early intervention at this young age, before mental health problems become entrenched in adolescence and young adulthood, may help to prevent the long-term impacts of childhood mental health problems, including adverse educational outcomes [12,13,14]. Children who received the counselling intervention were similar in terms of their mental health to individuals from a national population survey who had been in contact with specialist mental health and/or education services (see Table S6 in online supplementary information). Expanding primary school counselling services could increase access to support and reduce the pressure on oversubscribed CAMHS.

The counselling service analysed here is a targeted intervention that is offered within a universal whole-school mental health framework. The universal service has an ‘activating systems’ element, bringing into effect the engagement of parents and teachers in increasing wider mental health awareness and understanding in practice. The bolstering effect of the whole-school mental health provision could be a contributory factor to the positive outcomes demonstrated in this paper and there would be value in further research to explore the therapeutic effect of this universal approach on building on and sustaining these positive outcomes.

Strengths and limitations

Convergence of evidence from our analyses using different statistical methods and multiple informants provides strong support for the effectiveness of the school-based counselling intervention, while propensity score matching enabled us to identify a comparator group of children with similar characteristics to the intervention group but who had not received specialist mental health intervention. The study benefitted from use of the SDQ which is a validated and commonly used measure for the assessment of psychopathology in young people [24, 25], and the use of both parent and teacher reports strengthened our analysis. We were, however, unable to utilise teacher reports for the second part of the analysis examining trajectories of mental health, because these were not collected at enough time-points in the survey from which the comparator group was drawn. Given that our analysis focused only on primary schools, it is also unknown whether the counselling intervention would confer similar benefits for secondary school aged students, and this should be a priority for future research.

Propensity score matching is able to reduce the impact of imbalance in pre-treatment characteristics and thus enables more robust and less biased estimation of treatment effects in instances where a randomised controlled trial (RCT) cannot or has not been conducted. A limitation of propensity score matching is that it is unable to account for imbalance in unmeasured covariates where this imbalance cannot be addressed through correlation with measured covariates. However, a comparison of results from RCTs and observational studies using propensity scores in the field of cardiovascular disease found that while the magnitude of effects were often more extreme in observational studies, they were rarely different to a statistically significant degree from those reported in RCTs [32]. Furthermore, our sensitivity analysis (informed by methods proposed by VanderWeele and Arah [29]) suggested that our analysis was highly robust to unmeasured confounding. We were unable to match on socioeconomic factors such as household income or eligibility for free school meals as these were not measured in comparable ways in the two groups, although we were able to adjust for parental qualifications, which is a broad indicator of socioeconomic status [33]. Some imbalance between our two samples remained after matching, specifically in terms of child mental health, which was marginally worse in the intervention group, and parental mental health, which was worse in the comparator group. These variables were, however, included as covariates in the multi-level models.

Conclusions

Our findings demonstrate that a one-to-one counselling intervention delivered to children in UK primary schools leads to improvements in children’s mental health above and beyond that observed in a matched comparator group of children. These improvements in mental health were maintained over a 2 year follow-up period.

Availability of data and materials

The data from this study are not available for use by the wider research community at this time.

Code availability

The Stata code for this analysis is available from the authors on request.

References

Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE (2005) Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 62(6):593–602. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593

Kim-Cohen J, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Harrington H, Milne BJ, Poulton R (2003) Prior juvenile diagnoses in adults with mental disorder: developmental follow-back of a prospective-longitudinal cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry 60(7):709–717. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.60.7.709

Collishaw S (2015) Annual research review: secular trends in child and adolescent mental health. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 56(3):370–393. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12372

Sadler K, Vizard T, Ford T, Marcheselli F, Pearce N, Mandalia D, Davis J, Brodie E, Forbes N, Goodman A, Goodman R, McManus S (2018) Mental health of children and young people in England, 2017: summary of key findings. Mental Health of Children and Young People in England, 2017. NHS Digital, London. https://files.digital.nhs.uk/A6/EA7D58/MHCYP%202017%20Summary.pdf

Hagell A, Coleman J, Brooks F (2015) Key data on adolescence 2015. Association for Young People’s Health, London

YoungMinds (2018) Children’s mental health funding: where is it going? https://youngminds.org.uk/blog/childrens-mental-health-fundingwhere-is-it-going/. Accessed 1 Nov 2020

Holmes EA, O’Connor RC, Perry VH, Tracey I, Wessely S, Arseneault L, Ballard C, Christensen H, Cohen Silver R, Everall I, Ford T, John A, Kabir T, King K, Madan I, Michie S, Przybylski AK, Shafran R, Sweeney A, Worthman CM, Yardley L, Cowan K, Cope C, Hotopf M, Bullmore E (2020) Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1

Pierce M, Hope H, Ford T, Hatch S, Hotopf M, John A, Kontopantelis E, Webb R, Wessely S, McManus S, Abel KM (2020) Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population. Lancet Psychiatry 7(10):883–892. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30308-4

Vizard T, Sadler K, Ford T, Newlove-Delgado T, McManus S, Marcheselli F, Davis J, Williams T, Leach C, Mandalia D, Cartwright C (2020) Mental health of children and young people in England, 2020: wave 1 follow up to the 2017 survey. NHS Digital, London

Department of Health & Department for Education (2017) Transforming children and young people’s mental health provision: a green paper. Department of Health and Department for Education, London

Bonell C, Humphrey N, Fletcher A, Moore L, Anderson R, Campbell R (2014) Why schools should promote students’ health and wellbeing. BMJ 348:g3078. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g3078

Finning K, Ford T, Moore DA, Ukoumunne O (2020) Emotional disorder and absence from school: findings from the 2004 British Child and Adolescent Mental Health Survey. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 29(2):187–198. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-019-01342-4

Lereya ST, Patel M, dos Santos JPGA, Deighton J (2019) Mental health difficulties, attainment and attendance: a cross-sectional study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 28:1147–1152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-018-01273-6

Parker C, Tejerina-Arreal M, Henley W, Goodman R, Logan S, Ford T (2019) Are children with unrecognised psychiatric disorders being excluded from school? A secondary analysis of the British Child and Adolescent Mental Health Surveys 2004 and 2007. Psychol Med 49(15):2561–2572. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291718003513

Quilter-Pinner H, Ambrose A (2020) The ‘new normal’: the future of education after Covid-19. Institute for Public Policy Research, London

Sharpe H, Ford T, Lereya ST, Owen C, Viner RM, Wolpert M (2016) Survey of schools’ work with child and adolescent mental health across England: a system in need of support. Child Adolesc Mental Health 21(3):148–153. https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12166

Marshall L, Wishart R, Dunatchik A, Smith N (2017) Supporting mental health in schools and colleges: quantitative survey. Department for Education. DFE-RR697b

Baskin TW, Slaten CD, Crosby NR, Pufahl T, Schneller CL, Ladell M (2010) Efficacy of counselling and psychotherapy in schools: a meta-analytic review of treatment outcome studies 1Ψ7. Couns Psychol 38(7):878–903. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000010369497

Fox CL, Butler I (2009) Evaluating the effectiveness of a school-based counselling service in the UK. Br J Guid Couns 37(2):95–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069880902728598

Lee RC, Tiley CE, White JE (2009) The Place2Be: measuring the effectiveness of a primary school-based therapeutic intervention in England and Scotland. Couns Psychother Res 9(3):151–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733140903031432

Pearce P, Sewell R, Cooper M, Osman S, Fugard AJB, Pybis J (2017) Effectiveness of school-based humanistic counselling for psychological distress in young people: pilot randomized controlled trial with follow-up in an ethnically diverse sample. Psychol Psychother Theory Res Pract 90(2):138–155. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12102

Pro Bono Economics (2018) Economic evaluation of Place2Be’s counselling service in primary schools: a Pro Bono Economics report for Place2Be. Pro Bono Economics, London

Green H, McGinnity A, Meltzer H, Ford T, Goodman R (2005) Mental health of children and young people in Great Britain, 2004. The Office for National Statistics, London

Goodman R (2001) Psychometric properties of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 40(11):1337–1345. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200111000-00015

Stone LL, Otten R, Engels RCME, Vermulst AA, Janssens JMAM (2010) Psychometric properties of the parent and teacher versions of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire for 4- to 12-year-olds: a review. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 13(3):254–274. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-010-0071-2

Goldberg DP, Gater R, Sartorius N, Ustun TB, Piccinelli M, Gureje O, Rutter C (1997) The validity of two versions of the GHQ in the WHO study of mental illness in general health care. Psychol Med 27(1):191–197. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291796004242

StataCorp (2015) Stata statistical software: release 14. StataCorp LP, College Station

StataCorp (2017) Stata statistical software: release 15. StataCorp LP, College Station

Vanderweele TJ, Arah OA (2011) Bias formulas for sensitivity analysis of unmeasured confounding for general outcomes, treatments, and confounders. Epidemiology 22(1):42–52. https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181f74493

Singer JB, Willett JB (2003) Applied longitudinal data analysis: modelling change and event occurrence. Oxford University Press, New York

Wolpert M, Görzig A, Deighton J, Fugard AJB, Newman R, Ford T (2015) Comparison of indices of clinically meaningful change in child and adolescent mental health services: difference scores, reliable change, crossing clinical thresholds and ‘added value’—an exploration using parent rated scores on the SDQ. Child Adolesc Mental Health 20(2):94–101. https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12080

Dahabreh IJ, Sheldrick RC, Paulus JK, Chung M, Varvarigou V, Jafri H, Rassen JA, Trikalinos TA, Kitsios GD (2012) Do observational studies using propensity score methods agree with randomized trials? A systematic comparison of studies on acute coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J 33(15):1893–1901. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehs114

Galobardes B, Shaw M, Lawlor DA, Lynch JW, Davey Smith G (2006) Indicators of socioeconomic position (part 1). J Epidemiol Community Health 60(1):7–12. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2004.023531

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the counsellors at Place2Be for their diligent data collection, and the parents/carers who allowed us to learn from their child’s experience. We are grateful for the advice of the charity’s Research Advisory Group on this manuscript. We would also like to thank Nikhil Naag and Becky Salter from the Research and Evaluation Team for their support and help during the research process.

Funding

KF was funded by Place2Be and Research England’s Strategic Priorities Fund. The initial research for this manuscript was conducted as a service evaluation by Place2Be’s in-house evaluation team, and the addition of the comparator sample and subsequent analysis forms part of Policy@Exeter—a scoping programme that seeks to build the University of Exeter’s external profile and internal capacity for policy engaged research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SG and TF conceived the idea for the study in collaboration with Place2Be’s Research Advisory Group. JW managed the data collection process for Place2Be, KT conducted the pre- and post-intervention analyses, and KF performed the propensity matching and linear mixed effects models with support from GJMT and TF. All authors contributed to preparation of the manuscript for publication, which was led and coordinated by KF. KT and KF have verified the underlying data used for this analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

JW, KT and SG are employed by Place2Be, and KF’s time for the analysis involving propensity matching and linear mixed effects models was part-funded by Place2Be. TF works as an unpaid advisor to Place2Be.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Place2Be obtained parent/carer consent to collect and use their child’s data for evaluation purposes. Only anonymised data were used, in line with the charity’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) compliance. The BCAMHS had approval from Medical Research Ethics Committees. Ethical approval for the analysis presented here was granted by the University of Exeter College of Medicine and Health Ethics Committee (ref May20/D/241).

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Finning, K., White, J., Toth, K. et al. Longer-term effects of school-based counselling in UK primary schools. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 31, 1591–1599 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-021-01802-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-021-01802-w