Abstract

The Roadmap for Mental Health and Wellbeing Research in Europe (ROAMER) identified child and adolescent mental illness as a priority area for research. CAPICE (Childhood and Adolescence Psychopathology: unravelling the complex etiology by a large Interdisciplinary Collaboration in Europe) is a European Union (EU) funded training network aimed at investigating the causes of individual differences in common childhood and adolescent psychopathology, especially depression, anxiety, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. CAPICE brings together eight birth and childhood cohorts as well as other cohorts from the EArly Genetics and Life course Epidemiology (EAGLE) consortium, including twin cohorts, with unique longitudinal data on environmental exposures and mental health problems, and genetic data on participants. Here we describe the objectives, summarize the methodological approaches and initial results, and present the dissemination strategy of the CAPICE network. Besides identifying genetic and epigenetic variants associated with these phenotypes, analyses have been performed to shed light on the role of genetic factors and the interplay with the environment in influencing the persistence of symptoms across the lifespan. Data harmonization and building an advanced data catalogue are also part of the work plan. Findings will be disseminated to non-academic parties, in close collaboration with the Global Alliance of Mental Illness Advocacy Networks-Europe (GAMIAN-Europe).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The 2011 Roadmap for Mental Health and Wellbeing Research in Europe (ROAMER) [1,2,3] outlined six priorities for research in mental health, of which three are the focus of the EU funded Marie Skłodowska-Curie International Training Network CAPICE project: Childhood and Adolescence Psychopathology: unravelling the complex etiology by a large Interdisciplinary Collaboration in Europe:

-

(1)

Research into prevention, mental health promotion, and interventions in children, adolescents, and young adults;

-

(2)

Focus on the development and causal mechanisms of mental health symptoms, syndromes, and wellbeing across the lifespan (including older populations);

-

(3)

Develop and maintain international and interdisciplinary research networks and shared databases in the area of childhood and adolescence psychopathology.

To address these priorities, CAPICE brings together data from eight population-based birth and childhood cohorts, including twin cohorts, to focus on the causes of individual differences in childhood and adolescent psychopathology and its course (see Tables 1, 2). The CAPICE cohorts have collected longitudinal data on behavioral and emotional symptoms, lifestyle characteristics and environmental measures as well as genetic and epigenetic data (see Table 2), some also from parents. Data from other cohorts from the EArly Genetics and Life course Epidemiology (EAGLE) consortium [4], behaviour and cognition group, can also be involved in the studies, especially for genome-wide association meta-analysis (GWAMA). The EAGLE consortium is a collaboration of population-based birth, childhood and adolescent cohorts including the cohorts participating in CAPICE. These cohorts are mainly based in Western Europe and Australia as, to our knowledge, no comparable cohorts exist in other countries. If there are, they are very welcome to participate.

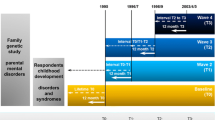

Efforts to prevent and treat childhood psychopathology need to be informed by a clear understanding of the aetiology of mental disorders, and factors that impact the development of a chronic course. Due to the genetically informative, longitudinal designs of the eight included cohorts, CAPICE is well positioned to address questions regarding the interplay of genetic and environmental factors in the development, course, and comorbidity patterns of child psychiatric conditions. Since CAPICE is an international training network, the analyses have been performed by 12 early stage researchers under the supervision of senior researchers at academic and non-academic sites across 5 European countries (Italy, The Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, and the United Kingdom). In this paper, we describe the six CAPICE objectives, as well as the methodological approaches that have been used and the initial results. The overview of the CAPICE research programme is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Overview of the CAPICE research programme: the aims are to investigate the influence of genetic, epigenetic, and transcriptomic variants on mental health symptoms, the interplay with the environment, and how these influences depend on age. Ultimately, these results will be integrated into a model predicting the persistence of symptoms

Objectives

-

(1)

Elucidate the role of genetic and environmental factors in mental health symptoms across childhood and adolescence, and to establish the overlap in genetic risk factors with other traits related to childhood mental health symptoms.

The projects that are part of this objective focus on the investigation of the overlap in genetic risk across phenotypes and ages, to explain comorbidity and persistence, respectively. Moreover, analyses will focus on disentangling the role of genetic and environmental factors in associations between childhood mental health symptoms and parental phenotypes or risk factors early in life.

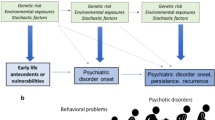

Previous research suggests that both genetic and non-genetic factors play a role in the development and persistence of mental health symptoms and disorders. Depending on age, gender, and type of mental health symptoms, genetic factors explain between 40 and 80% of their symptom variance between individuals [5], indicating that the contributions of genetic and environmental factors vary across disorders. Identifying mechanisms that underlie the persistence of symptoms and patterns of comorbidity are of specific importance in childhood psychopathology due to the potential impact of these disorders throughout the life course. Epidemiological studies have shown that about 50% of children with mental disorders still suffer from mental disorders in adulthood [6], including severe mental illnesses such as schizophrenia (SCZ) [7]. As comorbidity has been associated with worse prognosis [6, 8], it is essential to comprehend the mechanisms behind this.

It is also still unknown to what extent the associations between environmental factors and mental disorders are explained by causal processes, in which the environmental risk factor directly increases the risk for psychopathology, or by other processes such as, for example, gene–environment correlation, where the same genetic variants that influence a child’s risk for a mental disorder are associated with the child’s risk to be exposed to an unfavourable environment.

-

(2)

Identify genetic, epigenetic, and transcriptomic variants associated with mental health symptoms during childhood and adolescence.

There has been considerable progress in the field of psychiatric genetics with over two hundred genomic regions significantly associated with SCZ [9], bipolar disorder (BD) [10], depression [11, 12], attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) [13], and autism spectrum disorder (ASD) [14]. This has been achieved by large international collaborations such as the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium (PGC), performing meta-analyses with total sample sizes even up to 100,000 subjects [12]. The number of variants which have been associated with childhood psychopathology at genome-wide significance is still lower than for adult mental disorders [13, 14], but polygenic analyses have suggested that genetic variation in childhood mental disorders, as in adult disorders, is primarily due to many genetic variants of small effect [15]. This would mean that genome-wide association studies (GWAS) of child and adolescent psychopathology, which so far have been notably smaller than the large meta-analyses above, have likely been underpowered. By increasing the sample size and performing meta-analyses across the EAGLE cohorts, including the CAPICE cohorts, it may be possible to detect genome-wide significant associations.

In addition, because extended longitudinal data on mental health problems are available, it is possible to test whether genetic variants exert their influence across the lifespan or if their effect is restricted to a certain age period.

Finally, as previous work has also suggested that the impact of environmental factors on childhood psychopathology may be mediated by epigenetic variation (functional alterations in the genome that do not involve a change to DNA sequence [16]), identification of epigenetic differences associated to childhood mental disorders is also part of this objective.

-

(3)

Identify biological pathways associated with mental health symptoms and to validate potential drug targets based on these pathways.

The current identified genetic variants (SNPs) for psychiatric disorders only explain a small part of their variance [17,18,19]. However, the joint effect of all tested variants explains on average around 30% of the variance of psychiatric disorders [20], which makes it worth to investigate these variants further [21]. A key step in the pathway from variant identification in GWAS to the development of potential treatment or prevention approaches is the characterization of biologic pathways by which genetic variants affect disorders. For instance, follow-up analyses can specify whether associated variants are involved in the same biological pathways, which then can offer leads to novel drug targets or the repurposing of existing drugs that were initially developed for the treatment of other diseases [21,22,23].

In a recent study [22], a framework for drug repositioning is offered by associating transcriptomes imputed from GWAS data with drug-induced gene expression profiles from the Connectivity Map database. When applied to mental disorders, the method identified many candidates for repositioning, several upheld by preclinical or clinical evidence as they included known psychiatric medications or therapies considered in clinical trials [22]. Validation studies of these approaches have recognized antipsychotics as potential drug targets for mental disorders, confirming the approach may be a productive technique for developing drug therapies for childhood psychiatric conditions [24].

-

(4)

Build a prediction model that identifies children at the highest risk of developing chronic mental health symptoms.

To be able to provide treatment that takes into account the risk for persistence of symptoms, it is necessary to build a prediction model that supports stratifying children into groups at high and low risk for a severe, chronic symptom course. Similar risk calculators based on clinical symptoms and cognitive profiles have already been established for high-risk individuals for SCZ or BD [25,26,27]. Including environmental factors and multi-omic biomarkers may further improve the performance of the model [28].

-

(5)

Develop a sustainable international network of researchers in which collaboration is facilitated by data harmonization and information technology (IT) solutions enabling a joint analysis of data over cohorts.

The eight cohorts involved in CAPICE contain a wealth of data on childhood and adolescent mental health, but measures used to assess these traits differ across cohorts (see Table 2). One way to improve the power of studies combining results from multiple cohorts is to use common units of measurement. Using item-response theory (IRT) based test linking in these cohorts; it is possible to evaluate the extent to which dimensions from the individual instruments can be mapped onto dimensions that are shared across instruments. Such an analysis was successfully applied earlier to measures of personality [29].

-

(6)

Build a structure to disseminate the results to a broad audience of scientists, clinicians, patients and their parents, and the general public.

A limitation of research projects consists in the difficulty of properly disseminating their results, even if clinically relevant. Previous work has suggested that, even in targeted clinical research, it takes 17 years for 14% of discovery research to be integrated into physician practice [30]. Etiological research on mental disorders may include even broader dissemination gaps. To address this issue, CAPICE specifically aims to create structures allowing for the dissemination of project results to a broad audience, for instance, through a website and social network channels.

Methodology and results

Cohorts description

Before describing the approaches and results of each objective, we provide a general summary of the data collection of the eight CAPICE cohorts (see Tables 1, 2). All longitudinal cohorts have started either at birth or in childhood and use quantitative measures of psychopathology. These measures have been associated with clinical diagnoses [31,32,33,34] and are therefore widely used in clinical practice. The advantage of these dimensional measures is that they capture more of the variation present in the common population than dichotomous measures that only specify the presence or absence of a diagnosis. For genome-wide SNP data, methods to impute the genotypes are widely available allowing for the same genetic variants to be analysed over cohorts. All cohorts have been described in more detail elsewhere: ALSPAC [35,36,37], TEDS [38], GenR [39, 40], NTR [41,42,43], TCHAD [44], NFBC’86 [45], CATSS [46, 47], MOBA [48]. For a link to cohort-specific websites and for a detailed description of the cohorts (see Table 1). All data used for the analyses were collected under protocols that have been approved by the appropriate ethics committees, and studies were performed in accordance with the ethical standards.

Objective 1: Elucidate the role of genetic and environmental factors in mental health symptoms across childhood and adolescence, and to establish the overlap in genetic risk factors with other traits related to childhood mental health symptoms.

We refer to several excellent overviews for a description of the methods that can be used in genetic epidemiological studies analysing twin/family data and/or molecular genetic data [15, 49, 50]. In short, twin and family studies estimate the proportion of variance in a trait attributable to genetic and environmental factors by comparing the resemblance between pairs of relatives that differ in their relatedness. For example, if monozygotic twins, who are essentially 100% genetically identical, are more alike than dizygotic twins, who share on average 50% of their co-segregating alleles, this is an indication that genetic factors play a role in explaining differences between individuals for a certain trait. This model can be extended to include other family members, to longitudinal or multivariate designs, and to study gene–environment interaction (G × E), even without a direct measure of the environment [51,52,53].

It is also possible to address these questions using genotypic data obtained for GWAS. In GWAS, common single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) (positions in the DNA sequence that vary between individuals) measured across the whole genome are tested for their association with a trait. Many complex traits, like mental disorders, are influenced by multiple genetic loci. In this case, polygenic analyses, taking into account many SNPs, can be applied to investigate the cumulative impact of these SNPs on a trait, as well as on the co-occurrence of phenotypes or the persistence of symptoms over time [15, 49]. To this point, CAPICE researchers have performed twin and polygenic risk score analyses of the correlation between common mental health symptoms, such as internalizing problems and ADHD problems, and the stability of symptoms over time, including into adulthood.

Regarding the co-occurrence of symptoms, the covariance could be explained by one common factor, the so-called p-factor, which was found to be for 50–60% heritable. Moreover, genetic factors explained stability in this factor across ages. A polygenic p-factor risk score based on adult psychiatric disorders was also associated with the childhood p-factor [54].

The genetic association between adult psychiatric disorders and childhood and adolescents traits was further investigated with polygenic analyses. The PGS for adult depression, neuroticism, BMI, and insomnia were significantly positively associated with childhood ADHD, internalizing and social problems, while the PGS for subjective well-being and educational attainment showed negative associations [55]. Only bipolar disorder PGS did not yield any significant associations. Effect sizes were in general similar across age and phenotype, although the PGS for educational attainment was more strongly associated with ADHD and the BMI PGS with ADHD and social problems [55]. A follow-up study is currently on the way, performing multivariate analyses to shed more light on the pattern of associations (https://osf.io/7nkw8).

Genetic data can also be leveraged to estimate the average causal effect of specific environmental factors, such as perinatal factors, on child or adolescent psychopathology, using a method known as Mendelian randomization (MR). Several ongoing CAPICE projects have applied this approach to estimate the effect of prenatal risk factors, such as maternal smoking, on childhood mental health problems. It is important to recognize that the assumptions that are required for MR may not hold for all prenatal exposures and offspring outcomes [56]. Therefore, methods to identify violations of the MR assumptions are also evaluated and approaches that require fewer assumptions are tested.

Another method to analyse the mechanisms underlying parent-offspring associations is maternal genome-wide complex trait analysis (M-GCTA), which can be applied when parental genotypic data are also available. M-GCTA can be used to calculate whether the association between parent and offspring psychopathology is explained by an environmental effect on top of the effect of the genetic transmission [57]. Applying this method to the MoBa data indicated no such effects for anxiety and depression at age 8 [58]. Analyses on a larger so more powerful sample and including externalizing problems are currently performed.

Objective 2: Identify genetic, epigenetic, and transcriptomic variants associated with mental health symptoms during childhood and adolescence.

GWAS have provided insight into the genetic basis of quantitative variation in complex traits in the past decade [20]. By increasing the sample size and performing meta-analyses across the EAGLE cohorts, including the CAPICE cohorts, it may be possible to detect genome-wide significant associations and to detect age effects. A large-scale GWAMA using a multivariate method to analyse summary statistics that are not independent [59] focused on identifying genetic variants that influence the development and course of internalising symptoms from ages 3 to 18 (https://osf.io/w5adg/). Three gene-wide significant effects were detected as well as significant genetic associations with adult depression and related traits as well as with childhood traits. Another study explores the effect of (ultra) rare and common variation in genes specific to brain cell types on neuropsychiatric disorders (https://osf.io/uyv2s).

Previous work has also suggested that the impact of environmental factors on childhood psychopathology may be mediated by epigenetic variation, which consists of functional alterations in the genome that do not involve a change to DNA sequence [16]. While there are several forms of epigenetic variation, most epigenetic studies have focused on alterations in DNA methylation. Epigenome-wide association studies (EWAS) are performed to test the effect of maternal mid-pregnancy vitamin D on offspring cord blood methylation and of the association between variation in child peripheral and cord blood methylation and the subsequent development of ADHD.

Under very strong assumptions, mediation of the possible average causal effect of prenatal exposures on offspring psychiatric outcomes might be tested using an extension of the MR approach, incorporating genetic variants as proposed instruments for a particular prenatal exposure and for methylation at a specific locus. In certain contexts, this might be considered as a follow up to the present studies.

The association of prenatal maternal smoking with offspring blood DNA methylation has been investigated in individuals aged 16–48 years, and MR and mediation analyses have been performed to evaluate whether methylation markers have causal effects on disease outcomes in the offspring [60]. 69 differentially methylated CpGs in 36 genomic regions (P-value < 1 × 10−7) were found to be associated with exposure to maternal smoking in adolescents and adults and MR analyses delivered evidence for a causal role of four maternal smoking-related CpG sites on an increased risk of SCZ or inflammatory bowel disease [60]. Further studies analyse whether alcohol, tobacco, and caffeine use in pregnancy might be causally related to ADHD in the offspring using negative control and MR approaches (https://osf.io/wxu58) (https://osf.io/aqrxp).

Objective 3: Identify biological pathways associated with mental health symptoms and to validate potential drug targets based on these pathways.

Applying drug pathway analyses to the CAPICE GWAS results may permit us to derive hypotheses about potential drug targets and consequently possibilities for drug repurposing. The GWAMA on internalizing problems did not detect biological pathways (https://osf.io/w5adg/) so could not identify drug targets. This is not surprising as there were not many significantly associated genes.

Objective 4: Build a prediction model that identifies children at the highest risk of developing chronic mental health symptoms.

Using cohort data, as well as Swedish registry data, studies have been performed to predict outcomes of psychiatric symptoms in childhood and adolescence, focusing not only on mental disorders but also on somatic medical outcomes. As part of these analyses, a machine learning model including 474 predictors has been developed that can predict mental health problems in adolescence using data from the Child and Adolescent Twin Study in Sweden (CATSS) [61]. The suggested model would not be appropriate for medical purposes, but it helps to build better models to predict mental health outcomes [61].

Moreover, longitudinal analyses of data from the Swedish and Dutch twin registers indicated that adolescent anxiety is associated with psychiatric disorders later in life, even when adjusting for other mental health issues [62].

Objective 5: Develop a sustainable international network of researchers in which collaboration is facilitated by data harmonization and information technology (IT) solutions enabling a joint analysis of data over cohorts.

Using Item-Response Theory (IRT) based test linking it has been evaluated whether internalizing and ADHD symptoms assessed by different instruments can be mapped onto dimensions that are shared across instruments. These analyses were possible as some of the EAGLE cohorts (ABCD [63], Raine [64], and TEDS [38]), had measured mental health symptoms of the same individuals at the same age with two or more instruments. This could allow combining individual raw item data from different instruments to maximize statistical power.

In addition, to facilitate data analyses over cohorts, a searchable data catalogue is created. The variables important for the current project include demographic and family characteristics, individual’s school achievements, mental health measures (both psychopathology as well as wellbeing) by various raters (mother, father, self-report, teacher), pregnancy/perinatal measures, several general health and anthropometric measures, parenting, parental mental health, and several genomic measures and biomarkers in children and parents. To build a search engine that returns items including the searched term as well as related terms, text mining of available data documentation has been used to identify relationships between words. These results can then be used to develop an advanced search engine for the data catalogue. If “mental health” is, for example, the search term, the results will also include “emotional problems”, “behavioural problems”, and “psychiatric history of the mother”.

Objective 6: Build a structure to disseminate the results to a broad audience of scientists, clinicians, patients and their parents, and the general public.

To engage the general public with the results from these studies, CAPICE researchers have also created content designed for a lay audience on the website (http://www.capice-project.eu/index), Twitter (https://twitter.com/capice_project), YouTube (https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCgq8uIHiHE69IlcHoYCjwKg/featured?view_as=subscriber), LinkedIn and Facebook. CAPICE was also represented at the Greenman Festival in Wales, UK, and ESRs presented multiple times on several international conferences.

Discussion

Genetic research, including psychiatric genetics, has substantially moved forward due to large-scale collaborations in consortia, with meta-analyses being the rule rather than the exception. Due to developments in methodology, it is also possible to use the genome-wide genotypic data for purposes other than the identification of genetic risk variants. Given the small effect sizes, these analyses need large samples to achieve adequate statistical power. The cohorts brought together in CAPICE and the close collaboration with the EAGLE behavior and cognition group (https://www.eagle-consortium.org/) has provided an opportunity to perform these analyses and progress the field of child psychiatry by addressing essential questions like “Which genetic variants and biological pathways underlie the continuity of symptoms from childhood into adulthood?”; “Which factors explain the associations of childhood psychopathology with early life and familial risk factors?”; “What is the role of epigenetic factors in the development of the child and adolescent psychopathology?”; “Can we predict which children are at higher risk for poorer outcomes?”.

The ultimate aim is that these results will inform the development of future treatment and prevention efforts, including supporting the identification of novel targets for existing pharmacological agents. Moreover, having better prediction tools will bring precision medicine closer for child psychiatry as it provides the opportunity to test interventions specifically targeted at children at high or at low risk for the persistence of symptoms.

We acknowledge that the studies performed in the framework of CAPICE are largely restricted to children and families with a Western European genetic ancestry. Extending genetic data collection to children and families from other backgrounds is essential to gain knowledge on similarities and differences between groups from various backgrounds.

These analyses have all been performed as part of a training program for Early Stage Researchers. These researchers receive not only mentoring from senior academics on their specific projects but also a structured curriculum of workshops on child psychiatry, statistics, and dissemination strategy throughout the grant period. These workshops as well as the secondments at other participating institutions aim to build a new generation of creative and innovative researchers who might exert a relevant impact on academic and non-academic organizations.

In conclusion, CAPICE provides a broad package of training in the field of psychiatric genetics, going from harmonizing the phenotypes, the creation of facilities for analyses across cohorts and the actual state-of-the-art analyses, to the translation of the results for drug target validation or prediction models that can be used in the clinic for targeted interventions.

References

Wykes T, Haro JM, Belli SR et al (2015) Mental health research priorities for Europe. Lancet Psychiatry 2:1036–1042. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00332-6

Haro JM, Ayuso-Mateos JL, Bitter I et al (2014) ROAMER: roadmap for mental health research in Europe. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 23:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.1406

ROAMER. http://www.roamer-mh.org/index.php?page=1_1. Accessed 19 Jun 2019

Middeldorp CM, Felix JF, Mahajan A et al (2019) The early growth genetics (EGG) and EArly Genetics and Lifecourse Epidemiology (EAGLE) Consortia: design, results and future prospects. Eur J Epidemiol 34:9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-019-00502-9

Polderman TJC, Benyamin B, De Leeuw CA et al (2015) Meta-analysis of the heritability of human traits based on fifty years of twin studies. Nat Publ Gr 47:702. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.3285

Costello EJ, Maughan B (2015) Annual research review: optimal outcomes of child and adolescent mental illness. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 56:324. https://doi.org/10.1111/JCPP.12371

Maibing CF, Pedersen CB, Benros ME et al (2015) Risk of schizophrenia increases after all child and adolescent psychiatric disorders: a nationwide study. Schizophr Bull 41:963–970. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbu119

Angold A, Costello EJ, Erkanli A (1999) Comorbidity. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 40:57–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00424

Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium SWG of the PG, Ripke S, Neale BM et al (2014) Biological insights from 108 schizophrenia-associated genetic loci. Nature 511:421–427. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13595

Stahl EA, Breen G, Forstner AJ et al (2019) Genome-wide association study identifies 30 loci associated with bipolar disorder. Nat Genet 51:793–803. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-019-0397-8

Wray NR, Ripke S, Mattheisen M et al (2018) Genome-wide association analyses identify 44 risk variants and refine the genetic architecture of major depression. Nat Genet 50:668–681. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-018-0090-3

Howard DM, Adams MJ, Clarke T-K et al (2019) Genome-wide meta-analysis of depression identifies 102 independent variants and highlights the importance of the prefrontal brain regions. Nat Neurosci 22:343–352. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-018-0326-7

Demontis D, Walters RK, Martin J et al (2019) Discovery of the first genome-wide significant risk loci for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Nat Genet 51:63–75. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-018-0269-7

Grove J, Ripke S, Als TD et al (2019) Identification of common genetic risk variants for autism spectrum disorder. Nat Genet 51:431–444. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-019-0344-8

Wray NR, Lee SH, Mehta D et al (2014) Research review: polygenic methods and their application to psychiatric traits. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 55:1068–1087. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12295

Barker ED, Walton E, Cecil CAM (2018) Annual research review: DNA methylation as a mediator in the association between risk exposure and child and adolescent psychopathology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 59:303–322. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12782

Duncan LE, Ostacher M, Ballon J (2019) How genome-wide association studies (GWAS) made traditional candidate gene studies obsolete. Neuropsychopharmacology 44:1518–1523. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-019-0389-5

Sullivan PF, Daly MJ, O’Donovan M (2012) Genetic architectures of psychiatric disorders: the emerging picture and its implications. Nat Rev Genet 13:537–551. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg3240

Collins AL, Sullivan PF (2013) Genome-wide association studies in psychiatry: what have we learned? Br J Psychiatry 202:1–4. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.112.117002

Visscher PM, Wray NR, Zhang Q et al (2017) 10 Years of GWAS discovery: biology, function, and translation. Am J Hum Genet 101:5–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.06.005

Breen G, Li Q, Roth BL et al (2016) Translating genome-wide association findings into new therapeutics for psychiatry. Nat Neurosci 19:1392–1396. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.4411

So H-C, Chau CK-L, Chiu W-T et al (2017) Analysis of genome-wide association data highlights candidates for drug repositioning in psychiatry. Nat Neurosci 20:1342–1349. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.4618

Gaspar HA, Breen G (2017) Drug enrichment and discovery from schizophrenia genome-wide association results: an analysis and visualisation approach. Sci Rep 7:12460. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-12325-3

Gaspar HA, Gerring Z, Hübel C et al (2019) Using genetic drug-target networks to develop new drug hypotheses for major depressive disorder. Transl Psychiatry 9:117. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-019-0451-4

Birmaher B, Merranko JA, Goldstein TR et al (2018) A risk calculator to predict the individual risk of conversion from subthreshold bipolar symptoms to bipolar disorder I or II in youth. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 57:755-763.e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2018.05.023

Hafeman DM, Merranko J, Goldstein TR et al (2017) Assessment of a person-level risk calculator to predict new-onset bipolar spectrum disorder in youth at familial risk. JAMA Psychiatry 74:841–847. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.1763

Cannon TD, Yu C, Addington J et al (2016) An individualized risk calculator for research in prodromal psychosis. Am J Psychiatry 173:980–988. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.15070890

Chatterjee N, Shi J, García-Closas M (2016) Developing and evaluating polygenic risk prediction models for stratified disease prevention. Nat Rev Genet 17:392–406. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg.2016.27

van den Berg SM, de Moor MHM, McGue M et al (2014) Harmonization of neuroticism and extraversion phenotypes across inventories and cohorts in the genetics of personality consortium: an application of item response theory. Behav Genet 44:295–313. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10519-014-9654-x

Brownson RC, Kreuter MW, Arrington BA, True WR (2006) Translating scientific discoveries into public health action: how can schools of public health move us forward? Public Health Rep 121:97–103. https://doi.org/10.1177/003335490612100118

Achenbach T (2000) Manual for the ASEBA preschool forms & profiles : an integrated system of multi-informant assessment child behavior checklist for ages 1 1 2-5 language development survey caregiver-teacher. Univ. of Vermont Research Center for Children Youth & Families, Burlington Vt

Achenbach T (2001) Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms & profiles : an integrated system of multi-informant assessment. ASEBA, Burlington VT

Achenbach TM, Becker A, Döpfner M et al (2008) Multicultural assessment of child and adolescent psychopathology with ASEBA and SDQ instruments: research findings, applications, and future directions. J Child Psychol Psychiatry Allied Discip 49:251–275

Goodman R (1997) The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: a research note. J Child Psychol Psychiatry Allied Discip 38:581–586. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01545.x

Boyd A, Golding J, Macleod J et al (2013) Cohort Profile: the ‘Children of the 90s’—the index offspring of the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children. Int J Epidemiol 42:111–127. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dys064

Fraser A, Macdonald-Wallis C, Tilling K et al (2013) Cohort profile: the avon longitudinal study of parents and children: ALSPAC mothers cohort. Int J Epidemiol 42:97–110. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dys066

Northstone K, Lewcock M, Groom A et al (2019) Open peer review the avon longitudinal study of parents and children (ALSPAC): an update on the enrolled sample of index children in 2009. Wellcome Open Res 4:51. https://doi.org/10.12688/wellcomeopenres.15132.1

Haworth CMA, Davis OSP, Plomin R (2013) Twins early development study (TEDS): a genetically sensitive investigation of cognitive and behavioral development from childhood to young adulthood. Twin Res Hum Genet 16:117–125. https://doi.org/10.1017/thg.2012.91

Kooijman MN, Kruithof CJ, van Duijn CM et al (2016) The Generation R Study: design and cohort update 2017. Eur J Epidemiol 31:1243–1264. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-016-0224-9

Medina-Gomez C, Felix JF, Estrada K et al (2015) Challenges in conducting genome-wide association studies in highly admixed multi-ethnic populations: the Generation R Study. Eur J Epidemiol 30:317–330. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-015-9998-4

Van Beijsterveldt CEM, Groen-Blokhuis M, Hottenga JJ et al (2013) The young Netherlands twin register (YNTR): Longitudinal twin and family studies in over 70,000 children. Twin Res Hum Genet 16:252–267. https://doi.org/10.1017/thg.2012.118

Middeldorp CM, Hammerschlag AR, Ouwens KG et al (2016) A genome-wide association meta-analysis of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms in population-based pediatric cohorts. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 55:896-905.e6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2016.05.025

Kan KJ, Dolan CV, Nivard MG et al (2013) Genetic and environmental stability in attention problems across the lifespan: evidence from the Netherlands twin register. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 52:12–25. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329171400213X

Lichtenstein P, Tuvblad C, Larsson H, Carlström E (2007) The Swedish twin study of child and adolescent development: the TCHAD-study. Twin Res Hum Genet 10:67–73. https://doi.org/10.1375/twin.10.1.67

Järvelin MR, Hartikainen-Sorri A-L, Rantakallio P (1993) Labour induction policy in hospitals of different levels of specialisation. BJOG An Int J Obstet Gynaecol 100:310–315. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.1993.tb12971.x

Anckarsäter H, Lundström S, Kollberg L et al (2011) The child and adolescent twin study in Sweden (CATSS). Twin Res Hum Genet 14:495–508. https://doi.org/10.1375/twin.14.6.495

Brikell I, Larsson H, Lu Y et al (2020) The contribution of common genetic risk variants for ADHD to a general factor of childhood psychopathology. Mol Psychiatry 25:18091821. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-018-0109-2

Magnus P, Birke C, Vejrup K, et al (2016) Cohort profile update: the Norwegian mother and child cohort study (MoBa). Int J Epidemiol 382–388. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyw029

Maier RM, Visscher PM, Robinson MR, Wray NR (2018) Embracing polygenicity: a review of methods and tools for psychiatric genetics research. Psychol Med 48:1055–1067. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291717002318

Boomsma D, Busjahn A, Peltonen L (2002) Classical twin studies and beyond. Nat Rev Genet 3:872–882. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg932

Molenaar D, Dolan CV (2014) Testing systematic genotype by environment interactions using item level data. Behav Genet 44:212–231. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10519-014-9647-9

Molenaar D, van der Sluis S, Boomsma DI, Dolan CV (2012) Detecting specific genotype by environment interactions using marginal maximum likelihood estimation in the classical twin design. Behav Genet 42:483–499. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10519-011-9522-x

Schwabe I, van den Berg SM (2014) Assessing genotype by environment interaction in case of heterogeneous measurement error. Behav Genet 44:394–406. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10519-014-9649-7

Allegrini AG, Cheesman R, Rimfeld K et al (2020) The p factor: genetic analyses support a general dimension of psychopathology in childhood and adolescence. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 61:30–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13113

Akingbuwa WA, Hammerschlag AR, Jami ES et al (2020) Genetic associations between childhood psychopathology and adult depression and associated traits in 42998 individuals: a meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 77:715-728. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.0527

Evans DM, Davey Smith G (2015) Mendelian randomization: new applications in the coming age of hypothesis-free causality. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet 16:327–350. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-genom-090314-050016

Eaves LJ, Pourcain BS, Smith GD et al (2014) Resolving the effects of maternal and offspring genotype on dyadic outcomes in genome wide complex trait analysis ("M-GCTA"). Behav Genet 44:445–455. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10519-014-9666-6

Jami ES, Eilertsen EM, Hammerschlag AR et al (2020) Maternal and paternal effects on offspring internalizing problems: Results from genetic and family-based analyses. Am J Med Genet Part B Neuropsychiatr Genet 183:258–267. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.b.32784

Baselmans BML, Jansen R, Ip HF et al (2019) Multivariate genome-wide analyses of the well-being spectrum. Nat Genet 51:445–451. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-018-0320-8

Wiklund P, Karhunen V, Richmond RC et al (2019) DNA methylation links prenatal smoking exposure to later life health outcomes in offspring. Clin Epigenetics 11:97. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13148-019-0683-4

Tate AE, McCabe RC, Larsson H et al (2020) Predicting mental health problems in adolescence using machine learning techniques. PLoS ONE 15:e0230389. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0230389

Doering S, Lichtenstein P, Gillberg C et al (2019) Anxiety at age 15 predicts psychiatric diagnoses and suicidal ideation in late adolescence and young adulthood: results from two longitudinal studies. BMC Psychiatry 19:363. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-019-2349-3

van Eijsden M, Vrijkotte TG, Gemke RJ, van der Wal MF (2011) Cohort profile: the Amsterdam born children and their development (ABCD) study. Int J Epidemiol 40:1176–1186. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyq128

Straker L, Mountain J, Jacques A et al (2017) Cohort profile: the Western Australian pregnancy cohort (Raine) study-generation 2. Int J Epidemiol 46:308. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyw308

Acknowledgements

All cohorts are grateful to all families and participants who took part in these studies. We also acknowledge and appreciate the unique efforts of the research teams and practitioners contributing to the collection of this wealth of data. We thank Sonja Swanson for her contribution.

Funding

This work has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie CAPICE Project grant agreement number 721567 CAPICE.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author(s) have no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC)

The UK Medical Research Council and Wellcome (Grant ref: 102215/2/13/2) and the University of Bristol provide core support for ALSPAC. A comprehensive list of grants funding is available on the ALSPAC website. (http://www.bristol.ac.uk/alspac/external/documents/grant-acknowledgements.pdf).

GWAS data was generated by Sample Logistics and Genotyping Facilities at Wellcome Sanger Institute and LabCorp (Laboratory Corporation of America) using support from 23andMe.

The Child and Adolescent Twin Study in Sweden study (CATSS)

CATSS was supported by the Swedish Council for Working Life, funds under the ALF agreement, the Söderström Königska Foundation and the Swedish Research Council (Medicine, Humanities and Social Science, and SIMSAM).

Generation R study

The generation and management of GWAS genotype data for the Generation R Study was done at the Genetic Laboratory of the Department of Internal Medicine, Erasmus MC, the Netherlands. We thank Pascal Arp, Mila Jhamai, Marijn Verkerk, Lizbeth Herrera and Marjolein Peters for their help in creating, managing and QC of the GWAS database. The general design of Generation R Study is made possible by financial support from the Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Erasmus University Rotterdam, the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMw), the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO), the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport and the Ministry of Youth and Families. This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreements No 633595 (DynaHEALTH) and 733206 (LIFECYCLE).

The Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study (MOBA)

MOBA are supported by the Norwegian Ministry of Health and Care Services and the Ministry of Education and Research, NIH/NIEHS (contract noN01-ES-75558), NIH/NINDS (Grant No.1 UO1 NS 047537-01 and Grant No.2 UO1 NS 047537-06A1). Genotyping and data access was funded by the the Research Council of Norway grant agreements 229624 “HARVEST”, 223273 “NORMENT”, and 262177 “Intergenerational Transmission of Internalizing and Externalizing Psychopathological Spectra”.

The Netherlands Twin Register (NTR)

Data collection in the NTR was supported by NWO: Twin-family database for behavior genetics and genomics studies (480-04-004); “Spinozapremie” (NWO/SPI 56-464-14192; “Genetic and Family influences on Adolescent psychopathology and Wellness” (NWO 463-06-001); “A twin-sib study of adolescent wellness” (NWO-VENI 451-04-034); ZonMW “Genetic influences on stability and change in psychopathology from childhood to young adulthood” (912-10-020); “Netherlands Twin Registry Repository” (480-15-001/674); “Biobanking and Biomolecular Resources Research Infrastructure” (BBMRI-NL (184.021.007). We acknowledge FP7-HEALTH-F4-2007, grant agreement no. 201413 (ENGAGE), and the FP7/2007–2013 funded ACTION (grant agreement no. 602768) and the European Research Council (ERC-230374). Part of the genotyping was funded by the Genetic Association Information Network (GAIN) of the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health, Rutgers University Cell and DNA Repository (NIMH U24 MH068457-06), the Avera Institute, Sioux Falls, South Dakota (USA) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH R01 HD042157-01A1, MH081802, Grand Opportunity grants 1RC2 MH089951 and 1RC2 MH089995).

The Northern Finland Birth Cohorts 1986 (NFBC1986)

NFBCC1986 study has received financial support from EU QLG1-CT-2000-01643 (EUROBLCS) Grant no. E51560, NorFA Grant no. 731, 20056, 30167, USA/NIHH 2000 G DF682 Grant no. 50945, NIHM/MH063706, H2020-633595 DynaHEALTH action and Academy of Finland EGEA-project (285547).

Twin study of Child and Adolescent Development (TCHAD)

Supported by The Swedish Council for Working Life and the Swedish Research Council.

Twins Early Development Study (TEDS)

TEDS is supported by a program grant to RP from the UK Medical Research Council (MR/M021475/1), with additional support from the US National Institutes of Health (AG046938). The research leading to these results has also received funding from the European Research Council under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007–2013)/grant agreement no. 602768. RP is supported by a Medical Research Council Professorship award (G19/2).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rajula, H.S.R., Manchia, M., Agarwal, K. et al. Overview of CAPICE—Childhood and Adolescence Psychopathology: unravelling the complex etiology by a large Interdisciplinary Collaboration in Europe—an EU Marie Skłodowska-Curie International Training Network. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 31, 829–839 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-020-01713-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-020-01713-2