Abstract

Psychiatric symptoms and stress are on the increase among Swedish adolescents. We aimed to study the potential effect and feasibility of two Internet-based self-help programmes, one mindfulness based (iMBI) and the other music based in a randomised controlled trial that targeted adolescents. A total of 283 upper secondary school students in two Swedish schools were randomised to either a waiting list or one of the two programmes, on their own incentive, on schooltime. General psychiatric health (Symptoms Checklist 90), sleep quality (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index), and perceived stress (Perceived Stress Scale) were assessed before and after the interventions. In total, 202 participants answered the questionnaires. Less than 20 logged into each intervention and only 1 performed a full intervention (iMBI). No significant differences in any of the scales were found between those who logged in and those who did not. The potential effect of Internet-based self-help programmes was not possible to examine due to low compliance rates. Adolescents seem to have a very low compliance with Internet-based self-help programmes if left to their own incentive. There were no associations between the psychiatric and stress-related symptoms at baseline and compliance in any of the intervention groups, and no evidence for differences in compliance in relation to the type of programme. Additional studies are needed to examine how compliance rates can be increased in Internet-based self-help mindfulness programmes in adolescents, as the potentially positive effects of mindfulness are partly related to compliance rates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Psychiatric symptoms and perceived stress have increased among Swedish adolescents in recent decades [1,2,3]. Furthermore, there is evidence of significant associations between stress and psychopathology in children and adolescents from both cross-sectional [4, 5] and longitudinal studies [6,7,8,9]. Psychiatric symptoms and stress in adolescents can result in negative effects on health, well-being, and academic achievement [10], and seem to be independent of both the academic proficiency and urbanicity of the school [11]. In addition, there is a well-established association between reduced sleep quality and psychiatric symptoms in adolescents. Low sleep quality in adolescents is associated with behavioural problems and impairments in cognitive functioning and mood [12,13,14], which partly could explain the suggested increase in psychiatric symptoms and stress in Swedish adolescents over time [1, 15].

Internet-based psychotherapy (iPT) seems to be a promising treatment alternative in targeting psychiatric health problems; iPTs are relatively easy to access and could provide therapy to many people at a low cost [16]. This form of therapy may be particularly suitable for adolescents, since young people in general are familiar with using the Internet and it could also help many adolescents who refrain from seeking help in regular health care [17]. The effects of, as well as the compliance to, iPTs in adolescents remain, however, largely unstudied as very few studies have been based on younger participants [18].

Mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) have been adapted to the Internet as a vehicle of delivery and could therefore be suitable for adolescents. MBIs are well-renowned and well-validated psychotherapies [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28], and a meta-analysis in non-clinical settings concluded that mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) can reduce stress levels in healthy people [29]. A recent randomised controlled trial (RCT) in Sweden was conducted on adults with anxiety, depression, and stress and adjustment disorders treated in primary health care. The RCT compared group-based mindfulness therapy with individual-based cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and found that both therapies resulted in significant decreases in psychiatric symptoms [30]. Mindfulness-based therapies can also be combined with CBT, i.e. mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) [31].

Two recent review articles concerning mindfulness on adolescents concluded that it holds promise for students, in terms of improving cognitive performance and resilience to stress [32, 33]. Another study concluded that there are few possibilities to deliver MBIs in schools as few teachers, or other school personnel, are able to provide MBIs to the students [34]. The use of Internet-based MBIs (iMBI) may therefore be promising in terms of accessibility [16]. Several studies on adults have shown promise in using the Internet as a vehicle of psychotherapy delivery [35,36,37,38,39,40]. A narrative review concluded that iMBIs are feasible in terms of effectiveness, acceptability, and economy, and that further research examining different modes of iMBIs is warranted [41]. To our knowledge, no iMBI study on the potential effects as well as compliance has been carried out on adolescents. However, an Australian qualitative study has proposed iMBI as something desired by many adolescents [42].

Some previous studies have examined the potential effects of iMBI as well as the compliance in adults. The included clinical diagnoses and outcomes were relapse of major depression [39] and depression, anxiety and stress and adjustment disorders [35, 36, 38, 40, 43]. In general, these studies have found positive effects of iMBI, although the compliance has varied.

The first aim of this study was to investigate whether there is an effect of iMBI, delivered as an Internet-based self-help programme, on psychiatric and stress-related symptoms in adolescents. The second aim was to investigate the feasibility, in terms of compliance, of the intervention. The third aim was to investigate whether there is any association between psychiatric and stress-related symptoms at baseline and compliance to the intervention in the adolescents.

Methods

Study population

In the process of choosing the population, we opted for two different schools in terms of academic performance and urbanicity, to obtain an adequate sample that could be considered relatively representative of Swedish upper secondary school students. This selection is more thoroughly described in the baseline cross-sectional study [11], which represents a larger randomised, controlled, single-blinded study (CHAMPS) aimed to investigate whether iMBI could be used to prevent psychiatric and stress-related symptoms.

All Swedish-speaking students enrolled at the schools (adolescents aged 15–19 years) received information, initially through personal letters sent to their home addresses, and thereafter lectures in the schools (10-min oral information from the researchers in groups of 10–100 students with the possibility to ask questions).

We had three inclusion criteria: to be able to read and understand Swedish, to have an e-mail address, and to be willing to participate in an 8-week Internet-based self-help programme. A total of 1404 students were attending the two schools during the study period. The Swedish-speaking inclusion criterion excluded one subject, leaving 1403 possible participants. The second inclusion criterion did not lead to exclusion of any potential participants and the third criterion, willingness to participate in a stress reduction intervention, left 283 individuals all of whom gave written informed consent. The 283 participants were numbered consecutively after the arrival of their written consent form and were divided into seven groups, based on the three grades (first to third year of upper secondary school) and sex, to acquire all grades and both sexes in all intervention groups. This led to the construction of the following seven groups: first-grade male, first-grade female, second-grade male, second-grade female, third-grade male, third-grade female, and others. Others were classified as participants where grade and/or sex was missing. After being categorised in this way, the individuals in each of the seven groups were computer randomised into three intervention groups (A–C) by a statistician, i.e. each individual was assigned the letter A, B or C. The three treatment groups were iMBI, Internet-based music therapy (iMT), and waiting list. The initial seven groups were only created for randomisation purposes.

Of the 283 participants who gave written consent, 202 students—142 female, 50 male, and 10 where the information on sex and/or school was missing—also answered the Web-based questionnaires. The more rural school provided 45 students and the remaining 147 participants came from the more urban school. The mean age was 16.9 years and the median age 17 years (range 15–19 years).

Both intervention groups represented Internet-based self-help programmes and the coordinator at the institution handled all contact with the study subjects. This was to preserve the single-blindness of the intervention to the researchers. The participants were allowed by the schools to do a 10-min daily intervention during lesson time and were asked to do at least one intervention on each school day. There were no reminders given to the students, i.e. they had to participate in their appointed intervention on their own incentive. The 8-week interventions commenced on March 15, 2012. The participants could, via e-mail, contact two of the co-authors of this study (CA or FT), who are also physicians, if they felt that their psychiatric health deteriorated during the interventions.

Power was calculated for the main outcome of the study, improvement in global severity index (GSI) (see below) with the conventional values for significance level of 0.05 (α), and for power of 0.80 (β). With three groups to be compared, we used a one-way ANOVA pairwise two-sided equality calculation. We estimated a priori that with a population sample of 73 in each group, the GSI in the iMBI group would differ significantly from the waiting list group. This was based on a face-to-face mindfulness study in adults where GSI, our primary outcome, was measured [44]. In that study, the authors found an improvement in GSI from 0.91 (SD 0.71) to 0.53 (SD 0.51) and a median change of –43.2% after an 8-week MBSR course. According to the power calculation, we needed at least 219 participants, i.e. 73 in each group. To compensate for a presumed high pre-baseline dropout rate, we estimated the dropout rate before the first questionnaire to be 70%, based on two Swedish studies using GSI as an outcome in adolescents [45, 46]. We also made an estimation of the post-baseline dropout rate, of 44%, based on the responders that actually complied with an intervention in an adult iMBI study [43]. These assumptions led to an estimated total sample size of 1140 in the present study. We judged that the population of 1403 in the two chosen schools was adequate to address the study aims.

A recent systematic review of 36 studies [47] listed the different definitions/measures of dropout and engagement. As it does not seem as if a consensus has been reached on what terminology is most appropriate, we discriminated those who logged in with those who did not as follows: ‘logged in’ and ‘not logged in’. We believe that this represents the most accurate description of those students who enrolled in our study [47, 48].

Interventions

The two active interventions were Internet-based self-help programmes that were completely computerised without any human interference. They were based on modules of approximately 10 min and contained both video and audio material, but the focus was on the latter. Both interventions logged compliance in terms of log in identification, time at log in, and fulfilment of the session. They were accessible by any device that connects to the Internet, such as computers, smartphones, and tablets. All groups, including the waiting list group, got access to both interventions after all post-intervention questionnaires were completed. No further follow-up was performed.

Mindfulness-based intervention (iMBI)

The iMBI (In Swedish: Mindfulness Grundkurs 2.0 from Mindfulnesscenter AB, Sweden) was designed by Dr. Ola Schenström, a family physician and renowned national expert in Sweden on clinical mindfulness meditation. The programme is an 8-week course consisting of sessions of 10 min of mindfulness meditation twice daily, 6 days a week. The modules consist of standard mindfulness meditation techniques, such as body scan and mindfulness of breath, and other perceptions [49], and could be defined as an intervention based on mindfulness training [31]. The intervention incorporates elements from both MBSR [50] and more cognitively oriented parts from MBCT [51]. An iMBI, in a study on anxiety in adults, has used the same platform and guided meditations, but with cognitive material focused on anxiety [40]. For our study, a complete intervention was defined as at least 40 sessions, which is lower than the original programme but was deemed appropriate by the constructor of the programme.

Music therapy intervention (iMT)

We chose iMT as the active control to iMBI, as one meta-analysis on music therapy showed a good effect in stress reduction from listening to music both in itself and in combination with music-assisted relaxation techniques, and concluded that the best effect is on adolescents [52]. Listening to music is also something that adolescents are generally interested in and tend to do, of their own free will, when feeling stressed or emotionally challenged [53]. Furthermore, a small study on adolescents targeting depression with music therapy, which included active participation with instruments and interpretation in terms of painting, showed promising results [53]. In addition, the partial similarity between the two Internet-based self-help programmes makes these two groups comparable. For the present study, a complete intervention was defined as at least 40 sessions.

The iMT, Musikintervention, was designed with the aid of Professor Björn Ejdemo, MD, and visiting professor of music at the Australian National University, who made a preliminary selection of pieces of music. Per Vegfors, MD, specialist in child and adolescent psychiatry, assessed the appropriateness of the music from an adolescent psychiatric perspective. A total of ten non-vocal classical music pieces accessible on YouTube were chosen that met the criteria of (1) accessibility, i.e. being relatively easy to listen to for an untrained ear, (2) being of approximately 10 min in duration, and (3) recognisable as being calming or soothing. The programme Musikintervention (Paxx Media AB, Sweden) used streamed music videos from YouTube. See appendix for list of music and interpretations.

Questionnaires

We used three well-defined, well-validated, and reliable psychometric tests, before and after the intervention, that had previously been used on adolescents: the Symptoms Checklist 90 (SCL-90) [54], the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-14) [55], and the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) [56]. The combination of scales was chosen to give an insight into the students’ perceived stress (PSS-14) and likely outcomes of that stress, expressed as low-quality sleep (PSQI) and increased general psychiatric symptoms (SCL-90), as previous studies have shown bi-directionally stress-associated impairments in psychiatric symptoms and sleep [11]. The time required to fill in the questionnaires was adjusted to avoid questionnaire fatigue and keep good test–retest reliability.

Symptoms Checklist 90 (SCL-90)

To measure general psychiatric symptoms, we used the 90-item SCL-90, which uses a five-point Likert scale to assess overall psychiatric symptoms, including somatisation. The main outcome of the scale is the GSI, which is calculated as the total sum of the weights for each individual item divided by the total number of questions answered (with a minimum answer rate of 80%). The SCL-90 is commonly used in psychiatric evaluations and has a subscale measuring somatisation [54]. The SCL-90 has satisfactory internal consistency reliability [57, 58] and test–retest reliability over both a week [54] and 10 weeks [58]. The latter study also showed a good test–retest reliability coefficient for the GSI. The validity of the scale has been confirmed with regard to internal structure, factorial invariance, and convergent–discriminant validity [54, 57, 59, 60].

Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-14)

For measurement of perceived stress, we used the widely accepted 14-item PSS, constructed as a five-point Likert scale [55, 61]. The PSS only focuses on how the individual experiences the stressors and not on their magnitude. The PSS-14 scale has been shown to have good internal consistency and reliability (Cronbach’s alpha 0.75–0.89), and to have good test–retest reliability over 2 days to 4 weeks. It has been empirically validated in college students [62]. Measurements of perceived stress have higher ecological validity than physiological response parameters, self-report of psychiatric symptoms, and behavioural changes and stressors, such as major life changes [63].

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI)

We used the PSQI [56] to measure sleep quality. This index is an algorithm that calculates sleep quality based on nine parameters (one of which is divided into eight sub-items) and results in a numerical value with a cutoff level for low-quality sleep of more than five points. The PSQI has been shown to have good test–retest reliability for both the global score and the subscores in both short-term (2 days) and long-term (1–2 months) follow-ups, with an overall Cronbach’s alpha of 0.87. The PSQI has also shown good correlations with sleep logs and lower, but significant, correlations with polysomnography, confirming its validity [64].

The tests were sent via e-mail to the address given by each student when signing the informed consent document. The students were able to answer the tests when it suited them during a window of ten consecutive days. All questionnaires were handled by the Internet-based survey programme Inquisite Survey System (Inquisite Inc., Copenhagen, Denmark). Data were stored unidentified to guarantee privacy and blinding.

Statistical analysis

To examine aim 1, i.e. to investigate whether there was a potential effect of the Internet-based self-help programmes on psychiatric and stress-related symptoms assessed before and after the intervention, we aimed to compare the scores of the different scales before and after the intervention among the active participants. We also used Student’s t test to investigate whether the three groups differed at baseline. These comparisons were performed to check whether the randomisation procedure was successful. To examine aim 2, i.e. to investigate the feasibility in terms of compliance to the interventions with the two Internet-based self-help programmes, we used a CONSORT flowchart to display the dropout rates at the different steps of the study [65]. The comparison in dropout rate between the two intervention groups (iMBI and iMT) was done using Fisher’s two-tailed exact test calculated with the number of participants that were randomised to either intervention and the participants that finished at least one session of either intervention. The Fisher’s two-tailed exact test was used as we intended to analyse whether the relatively small samples deviated from the null hypothesis that there was a difference between the dropout rates between iMBI and iMT. To examine aim 3, i.e. to investigate whether there is any association between compliance to the intervention and psychiatric and stress-related symptoms at baseline, we compared the participants that logged in and completed at least one session and those who did not log into the self-help programme. We compared whether there was a difference in psychiatric and stress-related symptoms between those two groups, separately in each intervention group (iMBI and iMT). We used a scatter plot to check whether the distribution was skewed and used the non-parametric Wilcoxon rank-sum test if the distribution was skewed and the parametric Student’s t test when the data were normally distributed.

Statistical analysis was done using Stata IC 12 (Stata Corp, Texas, USA).

Results

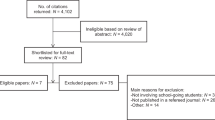

283 students were randomised into the three groups of the study: iMBI (n = 95), iMT (n = 94), or waiting list (n = 94); 1119 eligible candidates declined participation and 1 was excluded due to the language exclusion criterion. The randomisation worked well, as no significant differences were found between the three groups before the intervention in any of the scales. Of the 283 participants, 1 logged into both interventions and was excluded from the analysis. Of the 282 remaining students, 15 (15.8%) logged into the mindfulness intervention and 19 (20.4%) to the music intervention. Of the 19 persons who logged into the iMT, 4 did not complete any session, which was defined as playing at least 50% of the pieces of music. All but one person logging into the iMBI fulfilled at least one session. The flowchart is shown in Fig. 1. The distribution curve of sessions is shown in the supplementary Figure.

CONSORT flowchart of the study in terms of compliance to the interventions. The participant who logged into both interventions was excluded after the randomisation. The percentages in the intervention groups are the proportions of the randomised participants assigned to each intervention. Interventions: iMBI Internet-based mindfulness-based intervention, iMT Internet-based music therapy, and WL waiting list

Table 1 shows the comparisons between those who logged in and completed at least one session and those who did not log into the self-help programmes. No significant difference in any of the scales was found between those who logged in and completed at least one session and those who did not log into the self-help programmes.

Fisher’s exact test (two-tailed) gave a p value of 0.842 on comparing the number of participants who did at least one session of either intervention (iMBI or iMT), excluding the person who logged into both interventions.

The data below are only descriptive, since the compliance rate to the interventions was low. The compliance to the study protocol was 72% at baseline.

The only participant who did a complete intervention, defined as at least 40 sessions, performed 42 iMBI sessions and decreased the GSI by 31% (from 0.80 to 0.55). The same person decreased in PSQI from 8 to 7 and in PSS from 29 to 23. As regards the participants completing at least ten sessions (i.e. 25%), there were four in the iMBI group, three of whom answered the post-intervention questionnaires. In the iMT group, only one participant completed at least 25% of the sessions. The iMBI group decreased their mean GSI from 0.85 to 0.63 (SD 0.13 and 0.19, respectively). Their PSS decreased from 29.0 to 26.3 (SD 6.0 and 5.8, respectively). PSQI decreased from 9 to 8 (SD 4.6 and 5.5, respectively). The only iMT participant fared worse, with GSI increasing from 0.68 to 0.90, PSQI increasing from 6 to 7, but with PSS decreasing from 26 to 24.

None of the participants used the possibility to contact a physician via e-mail.

Discussion

Our main finding in this RCT is that the compliance rates of the two Internet-based self-help programmes were very low in adolescents (aim 2). This in itself is of interest, although the limited compliance did not allow us to investigate our first aim due to insufficient statistical power. However, the study provides useful information for the planning of future studies. We found no association between psychiatric and stress-related symptoms and compliance in any of the intervention groups (aim 3).

Our second aim, to determine feasibility in terms of compliance to the intervention, shows that the feasibility in conducting Internet-based self-help programmes in mindfulness may be limited in adolescents and that more research is needed on why the compliance is low in non-clinical samples. A limited compliance to an intervention may occur in several steps and present as failure to engage in the intervention or drop out from the protocol. In the present study, the low compliance after the randomisation/baseline assessment mainly occurred in two steps. First, a limited number of the adolescents actually logged in: only 15 of the 95 and 19 of the 94 adolescents logged into the iMBI and iMT, respectively. Second, the adolescents who actually logged in only completed a limited number of sessions and only one adolescent completed all 40 sessions.

The positive effects of mindfulness training are partly related to compliance rates. A recent meta-analysis on face-to-face MBIs in adolescents showed a positive correlation between minutes of mindfulness training and effect sizes [32]. Kuyken et al. reported that at least 50% attendance at the eight sessions of MBCT is considered necessary to receive an adequate treatment dose [66]. Thus, more knowledge is needed on the potential causes behind low compliance as well as methods to increase compliance with iMBI.

Potential causes behind and ways to overcome low compliance rates

According to Christensen et al. [67], there are three general approaches to investigate compliance in Internet-based interventions for anxiety and depression; these approaches can also be used in other types of patients and interventions. The first involves the examination of correlations to personality, demographic, and service delivery factors. The second includes the use of post-test qualitative investigations to obtain retrospective analyses of peoples’ perceptions of trial participation and barriers to the use of the Internet intervention, and the third involves experimental manipulation of variables thought to change compliance. The first approach has shown that lower compliance is associated with higher levels of emotional distress [67], certain types of conditions (higher compliance in chronic headache patients than in weight control patients), and male sex combined with lower GSI in cardiac patients [68]. Kabat-Zinn and Chapman-Waldrop found, however, no association between compliance and GSI in referred somatic and psychiatric patients [68]. Compliance rates may decrease in Internet-based [18, 69], longer, and preventive (rather than treatment) interventions in healthy population-based samples [70]. We found no evidence of an association between compliance rates and psychiatric and stress-related symptoms in our study population of non-clinical Swedish adolescents, which is in accordance with the study by Kabat-Zinn and Chapman-Waldrop who concluded that “there was no indication that severity of symptoms or illness affected outcome in terms of programme completion”. It is possible that feelings of shame or embarrassment could have been behind our students’ reluctance to log into the interventions during class time, although it also was possible for the students to log in outside class time. Another possibility is that some students may have found the intervention to be anxiety inducing, as previous studies have shown that emotional distress [67] decreases compliance.

The second and third approaches for compliance investigation according to Christensen et al. were not included as part of our study. Anecdotally, some students found the intervention ‘boring’ and others said that they did not complete the intervention due to lack of time. A teacher, school nurse, and school counsellor were of the opinion that stress, due to school issues, made the students less compliant to such interventions. Both students and personnel mentioned that stress interventions should be part of the curriculum to increase compliance and decrease stress. In an RCT conducted in Belgian schools, where mindfulness classes were part of the curriculum, the compliance rate was 85% [71].

Previous studies have examined how compliance to iPTs can be increased. For example, an Australian study found that compliance to iCBT in adults could be increased with e-mail reminders [69]. Some studies have found that guidance by trained psychotherapists augments the participation rate [72], while other studies, including university students, have found no such effect [73]. Material incentives have been shown to enhance compliance in children and adolescents as well as adults [74,75,76,77].

These potential causes and potential ways to increase compliance (see above) may be more or less salient during the different phases of the intervention, i.e. there may be different types of resistance towards entering and staying in the programme or, in this case, to log in or not log into the Internet-based self-help programme. For example, embarrassment and shame, gender, or a wish to belong to a specific intervention may deter students from logging in, whereas at later stages in the study other factors may lead to dropouts, such as psychological distress/anxiety, programme content, and lack of incentives. Some factors may lead to low compliance during the entire intervention, such as lack of time and stress, which may call for the inclusion of stress interventions into the curriculum.

Limitations and strengths

There are several limitations with the present study. We had no strategy to address any low compliance in the present study apart from our attempts to increase the sample size. However, an important aim was to study the potential feasibility of the two Internet-based self-help programmes in an RCT that targeted students in their adolescence, which represents a novel contribution. The low compliance rate did not allow for sufficient power to investigate our primary aim regarding the potential effect of the two interventions. In addition, we have only anecdotal information on why the adolescents dropped out. The use of questionnaires could have led to self-report bias, but questionnaires have been found to provide reliable data in Nordic adolescents [78]. Another limitation of this intervention is that it might be dubious to introduce stress management methods, such as mindfulness, with a sole focus on the individual while neglecting the overall organisation and structures in the school setting, which in itself may entail stress-inducing characteristics. Instead, a relational approach, which sees mindfulness as a socially contingent resource for communities, has been suggested as an alternative to the more common focus on the individual [79, 80]. Finally, although not being a direct limitation of the study, one could argue that all types of school interventions might compete with other important activities, such as schoolwork.

However, there are also several strengths that could be useful in future studies. For example, we included an active control group, listening to music, which is something that adolescents tend to do when feeling stressed or emotionally challenged [53]. A focus on listening is sometimes included in MBI, as in MBCT [51], and the partial similarity between the two interventions [81] makes these two groups comparable in terms of focus, although the focus in mindfulness is purposeful and without judgment. Another strength is that we evaluated the compliance in several steps [67]. The study design included reliable, well-validated questionnaires, and no adverse reactions to any of the interventions were reported. Finally, this is the first RCT that aimed to compare two different Internet-based self-help programmes in both male and female adolescents.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the compliance rates of the two Internet-based self-help programmes were very low in adolescents, which did not allow us to investigate our primary aim. The study provides, however, useful information for the planning of future studies in adolescents. Future studies need to examine potential causes behind why compliance rates may be low in Internet-based self-help programmes and how compliance rates can be increased in adolescents, as the potentially positive effects of mindfulness programmes on psychiatric symptoms and stress most likely are related to compliance rates.

References

Bremberg S (2006) Ungdomar, stress och psykisk ohälsa. Analyser och förslag till åtgärder. SOU 2006:77 (Official Report of the Swedish Government) Stockholm, Sweden

Petersen S (2010) Barns och ungdomars psykiska hälsa i Sverige : en systematisk litteraturöversikt med tonvikt på förändringar över tid. The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, Stockholm, Sweden

Wiklund M, Malmgren-Olsson E-B, Öhman A, Bergström E, Fjellman Wiklund A (2012) Subjective health complaints in older adolescents are related to perceived stress, anxiety and gender: a cross-sectional school study in Northern Sweden. BMC Public Health 12(1):993–1005

Compas BE (1987) Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence. Psychol Bull 101(3):393–403

Compas BE, Connor-Smith JK, Saltzman H, Thomsen AH, Wadsworth ME (2001) Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence: problems, progress, and potential in theory and research. Psychol Bull 127(1):87–127

Hammen C, Goodman-Brown T (1990) Self-schemas and vulnerability to specific life stress in children at risk for depression. Cogn Ther Res 14(2):215–227

Hilsman R, Garber J (1995) A test of the cognitive diathesis-stress model of depression in children: academic stressors, attributional style, perceived competence, and control. J Pers Soc Psychol 69(2):370–380

Rudolph KD, Lambert SF, Clark AG, Kurlakowsky KD (2001) Negotiating the transition to middle school: the role of self-regulatory processes. Child Dev 3:929

Schmeelk-Cone KH, Zimmerman MA (2003) A longitudinal analysis of stress in African American youth: predictors and outcomes of stress trajectories. J Youth Adolesc 32(6):419–430

Schraml K, Perski A, Grossi G, Makower I (2012) Chronic stress and its consequences on subsequent academic achievement among adolescents. J Educ Dev Psychol 2(1):69

Antonson C, Thorsén F, Sundquist K, Sundquist J (2014) Stress-related symptoms in Swedish adolescents: a study in two upper secondary schools. J Educ Dev Psychol 4(2):65–73

O’Brien LM (2009) The neurocognitive effects of sleep disruption in children and adolescents. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin North Am 18(4):813–823

Millman RP (2005) Excessive sleepiness in adolescents and young adults: causes, consequences, and treatment strategies. Pediatrics 115(6):1774–1786

Fallone G, Owens JA, Deane J (2002) Sleepiness in children and adolescents: clinical implications. Sleep Med Rev 6(4):287–306

Thorsén F, Antonson C, Sundquist J, Sundquist K (2016) Levels of perceived stress and psychiatric symptoms in Swedish adolescents. J Educ Dev Psychol 6(2):183–194

Andersson G (2009) Using the internet to provide cognitive behaviour therapy. Behav Res Ther 47(3):175–180

Hoek W, Schuurmans J, Cuijpers P, Koot HM (2009) Prevention of depression and anxiety in adolescents: a randomized controlled trial testing the efficacy and mechanisms of internet-based self-help problem-solving therapy. Trials 10:93

Aardoom JJ, Dingemans AE, Spinhoven P, Furth EF (2013) Treating eating disorders over the internet: a systematic review and future research directions. Int J Eat Disord 46(6):539–552

Chiesa A, Serretti A (2010) A systematic review of neurobiological and clinical features of mindfulness meditations. Psychol Med 40(8):1239–1252

Chiesa A, Serretti A (2011) Mindfulness based cognitive therapy for psychiatric disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res 187(3):441–453

Fjorback LO, Arendt M, Ørnbøl E, Fink P, Walach H (2011) Mindfulness-based stress reduction and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy—a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Acta Psychiatr Scand 124(2):102–119

Piet J, Hougaard E (2011) The effect of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for prevention of relapse in recurrent major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 31(6):1032–1040

Piet J, Würtzen H, Zachariae R (2012) The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on symptoms of anxiety and depression in adult cancer patients and survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol 80(6):1007–1020

Shennan C, Payne S, Fenlon D (2011) What is the evidence for the use of mindfulness-based interventions in cancer care? A review. Psycho-Oncolgy 20(7):681–697

Vøllestad J, Nielsen MB, Nielsen GH (2012) Mindfulness- and acceptance-based interventions for anxiety disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Psychol 51(3):239–260

Mars TS, Abbey H (2010) Mindfulness meditation practise as a healthcare intervention: a systematic review. Int J Osteopath Med 13(2):56–66

McCarney RW, Schulz J, Grey AR (2012) Effectiveness of mindfulness-based therapies in reducing symptoms of depression: a meta-analysis. Eur J Psychother Couns 14(3):279–299

Merkes M (2010) Mindfulness-based stress reduction for people with chronic diseases. Aust J Prim Health 16(3):200–210

Chiesa A, Serretti A (2009) Mindfulness-based stress reduction for stress management in healthy people: a review and meta-analysis. J Altern Complement Med 15(5):593–600

Sundquist J, Lilja A, Palmer K, Memon AA, Wang X, Johansson LM, Sundquist K (2015) Mindfulness group therapy in primary care patients with depression, anxiety and stress and adjustment disorders: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry 206(2):128–135

Baer RA (2003) Mindfulness training as a clinical intervention: a conceptual and empirical review. Clin Psychol Sci Pract 10(2):125–143

Zenner C, Herrnleben-Kurz S, Walach H (2014) Mindfulness-based interventions in schools—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychol 5:603. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00603

Felver JC, Celis-de Hoyos CE, Tezanos K, Singh NN (2016) A systematic review of mindfulness-based interventions for youth in school settings. Mindfulness 7(1):34–45

Crane RS, Kuyken W, Hastings RP, Rothwell N, Williams JMG (2010) Training teachers to deliver mindfulness-based interventions: learning from the UK experience. Mindfulness 1(2):74–86

Sjödin L, Vesa N (2013) Ett webbaserat kortprogram i mindfulness: Effekter på upplevd stress. University of Umeå, Umeå

Krusche A, Williams JMG, Cyhlarova E, King S (2012) Mindfulness online: a preliminary evaluation of the feasibility of a web-based mindfulness course and the impact on stress. BMJ Open 2(3):e000803

Lilja JL, Frodi-Lundgren A, Hanse JJ, Josefsson T, Lundh L-G, Sköld C, Hansen E, Broberg AG (2011) Five facets mindfulness questionnaire—reliability and factor structure: a Swedish version. Cogn Behav Ther 40(4):291–303

Cavanagh K, Strauss C, Cicconi F, Griffiths N, Wyper A, Jones F (2013) A randomised controlled trial of a brief online mindfulness-based intervention. Behav Res Ther 51(9):573–578

Dimidjian S, Beck A, Felder JN, Boggs J, Gallop R, Segal ZV (2014) Web-based mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for reducing residual depressive symptoms: an open trial and quasi-experimental comparison to propensity score matched controls. Behav Res Ther 63:83–89

Boettcher J, Åström V, Påhlsson D, Schenström O, Andersson G, Carlbring P (2014) Internet-based mindfulness treatment for anxiety disorders: a randomized controlled trial. Behav Ther 45(2):241–253

Krolikowski AM (2013) The Effectiveness of internet-based mindfulness interventions for physical and mental illnesses: a narrative review. Int J Cyber Behav Psychol Learn 3(4):84–96

Monshat K, Vella-Brodrick D, Burns J, Herrman H (2012) Mental health promotion in the internet age: a consultation with Australian young people to inform the design of an online mindfulness training programme. Health Promot Int 27(2):177–186

Glück TM, Maercker A (2011) A randomized controlled pilot study of a brief web-based mindfulness training. BMC Psychiatry 11:175

Carmody J, Reed G, Kristeller J, Merriam P (2008) Mindfulness, spirituality, and health-related symptoms. J Psychosom Res 64(4):393–403

Engström I, Norring C (2001) Risk for binge eating in a nonclinical Swedish adolescent sample: a repeated measure study. Eur Eat Disord Rev 9(6):427–441

Engström I, Norring C (2002) Estimation of the population “at risk” for eating disorders in a non-clinical Swedish sample: a repeated measure study. Eat Weight Disord Stud Anorex Bulim Obes 7(1):45

Beatty L, Binnion C (2016) A systematic review of predictors of, and reasons for, adherence to online psychological interventions. Int J Behav Med 23(6):776–794

Melville KM, Casey LM, Kavanagh DJ (2010) Dropout from internet-based treatment for psychological disorders. Br J Clin Psychol 49(4):455–471

Kabat-Zinn J (1982) An outpatient program in behavioral medicine for chronic pain patients based on the practice of mindfulness meditation: theoretical considerations and preliminary results. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 4(1):33–47

Kabat-Zinn J (2013) Full catastrophe living: using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness, 2nd edn. Piatkus, London

Segal ZV, Williams JG, Teasdale JD (2002) Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: a new approach to preventing relapse. Guilford, New York, London

Pelletier CL (2004) The effect of music on decreasing arousal due to stress: a meta-analysis. J Music Ther 41(3):192–214

Hendricks CB, Robinson B, Bradley LJ, Davis K (1999) Using music techniques to treat adolescent depression. J Humanist Couns Educ Dev 38(1):39

Derogatis LR (1994) SCL-90-R administration, scoring, and procedures manual—third edition. NCS Pearson Inc, Minneapolis

Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R (1983) A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav 24(4):385–396

Buysse DJ, Reynolds Iii CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ (1989) The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res 28(2):193–213

Derogatis LR, Rickels K, Rock AF (1976) The SCL-90 and the MMPI: a step in the validation of a new self-report scale. Br J Psychiatry 128(3):280–289

Horowitz LM, Rosenberg SE, Baer BA, Ureño G, Villaseñor VS (1988) Inventory of interpersonal problems: psychometric properties and clinical applications. J Consult Clin Psychol 56(6):885–892

Koeter MWJ (1992) Validity of the GHQ and SCL anxiety and depression scales: a comparative study. J Affect Disord 24(4):271–279

Wiznitzer M, Verhulst FC, Van den Brink W, Koeter M (1992) Detecting psychopathology in young adults: the young adult self report, the general health questionnaire and the symptom checklist as screening instruments. Acta Psychiatr Scand 86(1):32–37

Cohen S, Janicki-Deverts D, Miller GE (2007) Psychological stress and disease. JAMA J Am Med Assoc 298(14):1685–1687

Lee EH (2012) Review of the psychometric evidence of the Perceived Stress Scale. Asian Nurs Res 6(4):121–127

Lavoie JAA, Douglas KS (2012) The Perceived Stress Scale: evaluating configural, metric and scalar invariance across mental health status and gender. J Psychopathol Behav Assess 34(1):48–57

Backhaus J, Junghanns K, Broocks A, Hohagen F, Riemann D (2002) Test-retest reliability and validity of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index in primary insomnia. J Psychosom Res 53(3):737–740

Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG, Group* C (2001) The consort statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomized trials. Ann Intern Med 134(8):657–662

Kuyken W, Watkins E, Holden E, White K, Taylor RS, Byford S, Evans A, Radford S, Teasdale JD, Dalgleish T (2010) How does mindfulness-based cognitive therapy work? Behav Res Ther 48(11):1105–1112

Christensen H, Griffiths KM, Farrer L (2009) Adherence in internet interventions for anxiety and depression. J Med Internet Res 11(2):e13

Kabat-Zinn J, Chapman-Waldrop A (1988) Compliance with an outpatient stress reduction program: rates and predictors of program completion. J Behav Med 11(4):333–352

Titov N, Dear BF, Johnston L, Lorian C, Zou J et al (2013) Improving adherence and clinical outcomes in self-guided internet treatment for anxiety and depression: randomised controlled trial. PLoS ONE 8(7):e62873. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0062873

Stice E, Shaw H, Bohon C, Marti CN, Rohde P (2009) A meta-analytic review of depression prevention programs for children and adolescents: factors that predict magnitude of intervention effects. J Consult Clin Psychol 77(3):486–503

Raes F, Griffith JW, Gucht K, Williams JMG (2014) School-based prevention and reduction of depression in adolescents: a cluster-randomized controlled trial of a mindfulness group program. Mindfulness 5(5):477–486

Andersson G, Cuijpers P, Carlbring P, Riper H, Hedman E (2014) Guided internet-based vs. face-to-face cognitive behavior therapy for psychiatric and somatic disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World Psychiatry 13(3):288–295

Tillfors M, Carlbring P, Andersson G, Furmark T, Lewenhaupt S, Spak M, Eriksson A, Westling BE (2008) Treating university students with social phobia and public speaking fears: internet delivered self-help with or without live group exposure sessions. Depression Anxiety 25(8):708–717

Bogels S, Hoogstad B, van Dun L, de Schutter S, Restifo K (2008) Mindfulness training for adolescents with externalizing disorders and their parents. Behav Cogn Psychother 36(2):193–209

Giuffrida A, Torgerson DJ (1997) Should we pay the patient? Review of financial incentives to enhance patient compliance. Br Med Assoc 315:703–707

Yokley JM, Glenwick DS (1984) Increasing the immunization of preschool children; an evaluation of applied community interventions. J Appl Behav Anal 17(3):313–325

Smith PB, Weinman ML, Johnson TC, Wait RB (1990) Incentives and their influence on appointment compliance in a teenage family-planning clinic. J Adolesc Health Care 11(5):445–448

Breidablik HJ, Meland E, Lydersen S (2009) Self-rated health during adolescence: stability and predictors of change (Young-HUNT study, Norway). Eur J Pub Health 19(1):73–78

Arthington P (2016) Mindfulness: a critical perspective. Community Psychol Glob Perspect 1(2):87–104

Stanley S (2012) Mindfulness: towards a critical relational perspective. Soc Pers Psychol Compass 6(9):631–641

Graham R (2010) A cognitive-attentional perspective on the psychological benefits of listening. Music Med Interdiscip J 2(3):167–173

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank both the staff and the students of the two participating schools: Bergska Skolan and Gymnasieskolan Spyken. We would also like to thank Patrick Reilly for correcting the language in the draft and Karolina Palmér for statistical aid. We are furthermore most obliged to Ola Schenström at Mindfulnesscenter AB, who provided the mindfulness intervention free of charge and also for giving us access to its log files. We are also indebted to Professor Björn Ejdemo, who chose the music, and Dr Per Vegfors who analysed the music from an adolescent psychiatric perspective.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding

The Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life, and Welfare (In Swedish: Forte) and the Swedish Research Council to Jan Sundquist.

Ethical standards

We obtained the ethical permission for the study from the local ethics committee (Etikprövningsnämnden) in Lund, Sweden (Reference No. 2011/345). The study was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov before it commenced (Reference No. NCT01457222). The study was designed and performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was provided by each participant.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Antonson, C., Thorsén, F., Sundquist, J. et al. Upper secondary school students’ compliance with two Internet-based self-help programmes: a randomised controlled trial. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 27, 191–200 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-017-1035-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-017-1035-6