Abstract

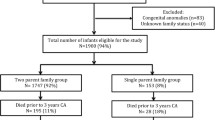

ADHD is more common in children born preterm than at term. The purpose of the study was to examine if, and to what extent, ADHD symptoms are associated with minor neurodevelopmental impairments (NDI) in extremely preterm children. In a national population-based cohort with gestational age 22–27 weeks or birth weight <1,000 g assessed at 5 years of age, scores on Yale Children’s Inventory (YCI) scales (seven scales) were related to normal functions vs. NDI defined as mild impairments in cognitive function (IQ 70–84), motor function (Movement Assessment Battery for children score > the 95th percentile or freely ambulatory cerebral palsy), vision (correctable), and hearing (no hearing aid). YCI was completed for 213 of 258 eligible children (83 %). Children with minor NDIs (n = 98) had significantly higher scores (more ADHD symptoms) than those without NDI (n = 115) on the YCI scales of Attention, Tractability, Adaptability and Total score. Increasing numbers of minor NDIs were associated with higher mean YCI scores. In multivariate analysis only decreased hearing, IQ, and male gender were significantly associated with scores on the Attention scale. Thirty-three children (16 %) had scores >3 on the Attention scale (probably ADHD), and the proportion was significantly higher for those with mild NDIs compared to those without (Odds ratio = 2.7, 95 % CI 1.3–6.0). Children born extremely preterm with minor NDIs were more likely to have ADHD symptoms than those with no NDI, and increasing number of minor NDIs were associated with more ADHD symptoms.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Samara M et al (2008) Pervasive behavior problems at 6 years of age in a total-population sample of children born at </= 25 weeks of gestation. Pediatrics 122(3):562–573

Delobel-Ayoub M et al (2009) Behavioral problems and cognitive performance at 5 years of age after very preterm birth: the EPIPAGE study. Pediatrics 123(6):1485–1492

Anderson PJ et al (2011) Attention problems in a representative sample of extremely preterm/extremely low birth weight children. Dev Neuropsychol 36(1):57–73

Elgen SK et al (2012) Mental health at 5 years among children born extremely preterm: a national population-based study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 21(10):583–589

Hack M et al (2009) Behavioral outcomes of extremely low birth weight children at age 8 years. J Dev Behav Pediatr 30(2):122–130

Lindstrom K, Lindblad F, Hjern A (2011) Preterm birth and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in schoolchildren. Pediatrics 127(5):858–865

Leversen KT et al (2011) Prediction of neurodevelopmental and sensory outcome at 5 years in Norwegian children born extremely preterm. Pediatrics 127(3):e630–e638

Johnson S et al (2009) Neurodevelopmental disability through 11 years of age in children born before 26 weeks of gestation. Pediatrics 124(2):e249–e257

Marlow N et al (2005) Neurologic and developmental disability at six years of age after extremely preterm birth. N Engl J Med 352(1):9–19

Bhutta AT et al (2002) Cognitive and behavioral outcomes of school-aged children who were born preterm: a meta-analysis. JAMA 288(6):728–737

Larroque B et al (2008) Neurodevelopmental disabilities and special care of 5-year-old children born before 33 weeks of gestation (the EPIPAGE study): a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet 371(9615):813–820

Hack M et al (2005) Chronic conditions, functional limitations, and special health care needs of school-aged children born with extremely low-birth-weight in the 1990s. JAMA 294(3):318–325

Kaptein S et al (2008) Mental health problems in children with intellectual disability: use of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire. J Intellect Disabil Res 52(Pt 2):125–131

Emerson E (2005) Use of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire to assess the mental health needs of children and adolescents with intellectual disabilities. J Intellect Dev Disabil 30(1):14–23

Markestad T et al (2005) Early death, morbidity, and need of treatment among extremely premature infants. Pediatrics 115(5):1289–1298

Westby Wold SH et al (2009) Neonatal mortality and morbidity in extremely preterm small for gestational age infants: a population based study. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 94(5):F363–F367

Palisano R et al (1997) Development and reliability of a system to classify gross motor function in children with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol 39(4):214–223

Wechsler D (1999) Wechsler preschool and primary scale of intelligence-revised, Swedish edn. Psykologförlaget AB, Stockholm

Henderson S, Sugden D (1996) The movement assessment battery for children, Swedish edn. Psykologförlaget AB, Stockholm

Shaywitz SE et al (1986) Yale Children’s Inventory (YCI): an instrument to assess children with attentional deficits and learning disabilities. I. Scale development and psychometric properties. J Abnorm Child Psychol 14(3):347–364

Shaywitz SE, Shaywitz BA, Jamner AH, Gillespie SM (1986b) Diagnosis of attention deficit disorder: development and validation of a diagnostic rule utilizing the Yale Children’s inventory. Annals of Neurology 20:415 (abstract)

Shaywitz SE et al (1988) Concurrent and predictive validity of the Yale Children’s Inventory: an instrument to assess children with attentional deficits and learning disabilities. Pediatrics 81(4):562–571

Shaywitz BA, Shaywitz SE (1989) Pediatric neurology, principles and practice. Learning disabilities and attention disorders. Mosby Company, St. Louis

Shaywitz SE, Holahan JM, Marchione KE, Sadler AE and Shaywitz BA (1992) The Yale Children’s Inventory: normative data and their implications for the diagnosis of attention deficit disorder in children. In: Shaywitz SE and Shaywitz BA (eds) Attention deficit disorder comes of age; toward the 21st century. Pro’ed, Series Editors

Sommerfelt K et al (2001) Behavior in term, small for gestational age preschoolers. Early Hum Dev 65(2):107–121

Johnson S et al (2010) Psychiatric disorders in extremely preterm children: longitudinal finding at age 11 years in the EPICure study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 49(5):453–463 e1

Arnaud C et al (2007) Prevalence and associated factors of minor neuromotor dysfunctions at age 5 years in prematurely born children: the EPIPAGE study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 161(11):1053–1061

Smits-Engelsman B, Hill EL (2012) The relationship between motor coordination and intelligence across the IQ range. Pediatrics 130(4):e950–e956

Acknowledgments

The study was funded by the Norwegian Foundation for Health and Rehabilitation through The Unexpected Child Death Society of Norway, the Research Council of Norway, Helse Vest Hospital Trust, University of Bergen, and Uni Health Center for Child and Adolescent Mental Health. Other members of the Norwegian Extreme Prematurity Study are as follows: Pediatrics: Arild Rønnestad, Oslo University Hospital, Rikshospitalet, Oslo; Per Ivar Kaaresen, University Hospital of North Norway, Tromsø; Theresa Farstad, Akershus University Hospital, Lørenskog; Janne Skranes, Oslo University Hospital, Ullevål University Hospital, Oslo; Ragnhild Støen, St Olav‘s Hospital, Trondheim University Hospital, Trondheim; Siren Rettedal, Stavanger University Hospital, Stavanger, and Haukeland University Hospital, Bergen; Lorentz M Irgens, University of Bergen, Bergen; Sven Harald Andersen, Østfold Hospital, Fredrikstad; Jørgen Hurum, Innlandet Hospital, Lillehammer; Sveinung Slinde, Telemark Hospital, Skien; Jorunn Ulriksen and Kåre Danielsen, Sørlandet Hospital, Kristiansand; Jon Skranes, Sørlandet Hospital, Arendal; Sabine Brügman, Buskerud Hospital, Drammen; Lars Tveiten, Innlandet Hospital, Elverum; Fabian Bergqvist, Førde Hospital, Førde; Andreas Andreassen, Fonna Hospital, Haugesund, Lutz Nietsch, Ålesund Hospital, Ålesund; Ingebjørg Fagerli, Nordland Hospital, Bodø; Bjørn Myklebust, Levanger Hospital, Levanger. For technical assistance, we thank Inger Elise Engelund and Magnhild Viste, Medical Birth Registry of Norway, Locus of Registry-Based Epidemiology. The authors thank biostatistician Geir Egil Eide for advice on statistics.

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical standards

This study has been approved by the Regional Committee on Medical Research Ethics and the Norwegian Data Inspectorate, and has, therefore, been performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. Prior to their inclusion in the study, parents gave written informed consent.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Elgen, S.K., Sommerfelt, K., Leversen, K.T. et al. Minor neurodevelopmental impairments are associated with increased occurrence of ADHD symptoms in children born extremely preterm. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 24, 463–470 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-014-0597-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-014-0597-9