Abstract

Objective

This study aims to clinically evaluate the treatment of mandibular class II furcation defects with enamel matrix derivative (EMD) and/or a bone substitute graft made of β-tricalcium phosphate/hydroxyapatite (βTCP/HA).

Materials and methods

Forty-one patients, presenting a mandibular class II buccal furcation defect, probing pocket depth (PPD) ≥4 mm and bleeding on probing, were included. They were randomly assigned to the groups: 1—EMD (n = 13); 2—βTCP/HA (n = 14); 3—EMD + βTCP/HA (n = 14). Plaque index (PI), gingival index (GI), relative gingival margin position (RGMP), relative vertical and horizontal attachment level (RVCAL and RHCAL), and PPD were evaluated at baseline and 6 and 12 months. The mean horizontal clinical attachment level gain was considered the primary outcome variable.

Results

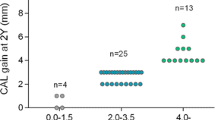

No significant intragroup differences were observed for RGMP, but significant changes were observed for RVCAL, RHCAL, and PPD for all groups (p < 0.05). After 12 months, the mean horizontal clinical attachment level gain was 2.77 ± 0.93 mm for EMD, 2.64 ± 0.93 mm for βTCP/HA, and 2.93 ± 0.83 mm for EMD + βTCP/HA, with no significant differences among the groups. At the end of the study, 85.3 % of the sites were partially closed; however, no complete closure was observed.

Conclusion

EMD + βTCP/HA does not provide a significant advantage when compared to the isolated approaches. All three tested treatments promote significant improvements and partial closure of class II buccal furcation defects. Based on its potential to induce periodontal regeneration, EMD may be considered an attractive option for this type of defect, but complete closure remains an unrealistic goal.

Clinical relevance

The partial closure of buccal furcation defects can be achieved after the three tested approaches. However, the combined treatment does not provide a significant benefit when compared to the isolated approaches.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Cattabriga M, Pedrazzoli V, Wilson TG (2000) The conservative approach in the treatment of furcation lesions. Periodontol 2000 22:133–153

Pontoriero R, Lindhe J (1995) Guided tissue regeneration in the treatment of degree II furcations in maxillary molars. J Clin Periodontol 22(10):756–763

Becker W, Becker BE, Mellonig J, Caffesse RG, Warrer K, Caton JG et al (1996) A prospective multi-center study evaluating periodontal regeneration for class II furcation invasions and intrabony defects after treatment with a bioabsorbable barrier membrane: 1-year results. J Periodontol 67(7):641–649

Mellonig JT (1999) Enamel matrix derivative for periodontal reconstructive surgery: technique and clinical and histologic case report. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 19(1):8–19

Haase HR, Bartold PM (2001) Enamel matrix derivative induces matrix synthesis by cultured human periodontal fibroblast cells. J Periodontol 72(3):341–348

Sculean A, Windisch P, Gc C, Donos N, Brecx M, Treatment RE et al (2001) Treatment of intrabony defects with enamel matrix proteins and guided tissue regeneration. J Clin Periodontol 28(5):397–403

Galli C, Macaluso GM, Guizzardi S, Vescovini R, Passeri M, Passeri G (2006) Osteoprotegerin and receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa B ligand modulation by enamel matrix derivative in human alveolar osteoblasts. J Periodontol 77(7):1223–1228

Walter C, Jawor P, Bernimoulin J (2006) Moderate effect of enamel matrix derivative (Emdogain W Gel) on Porphyromonas gingivalis growth in vitro. J Dent Res 171–176

Arweiler NB, Auschill TM, Donos N, Sculean A (2002) Antibacterial effect of an enamel matrix protein derivative on in vivo dental biofilm vitality. Clin Oral Investig 6(4):205–209

Keila S, Nemcovsky CE, Moses O, Artzi Z, Weinreb M (2004) In vitro effects of enamel matrix proteins on rat bone marrow cells and gingival fibroblasts. J Dent Res 83(2):134–138

Jepsen S, Heinz B, Jepsen K, Arjomand M, Hoffmann T, Richter S et al (2004) A randomized clinical trial comparing enamel matrix derivative and membrane treatment of buccal class II furcation involvement in mandibular molars. Part I: study design and results for primary outcomes. J Periodontol 75(8):1150–1160

Meyle J, Gonzales JR, Bödeker RH, Hoffmann T, Richter S, Heinz B et al (2004) Part II: secondary outcomes. 75(9)

Donos N, Glavind L, Karring T, Sculean A (2003) Clinical evaluation of an enamel matrix derivative in the treatment of mandibular degree II furcation involvement: a 36-month case series. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 23(5):507–512

Chitsazi MT, Mostofi Zadeh Farahani R, Pourabbas M, Bahaeddin N (2007) Efficacy of open flap debridement with and without enamel matrix derivatives in the treatment of mandibular degree II furcation involvement. Clin Oral Investig 11(4):385–389

Reynolds MA, Aichelmann-Reidy ME, Branch-Mays GL (2010) Regeneration of periodontal tissue: bone replacement grafts. Dent Clin N Am 54(1):55–71

Stahl SS, Froum SJ (1987) Histologic and clinical responses to porous hydroxylapatite implants in human periodontal defects. Three to twelve months postimplantation. J Periodontol 58(10):689–695

Hashimoto-Uoshima M, Ishikawa I, Kinoshita A, Weng HT, Oda S (1995) Clinical and histologic observation of replacement of biphasic calcium phosphate by bone tissue in monkeys. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 15(2):205–213

Hamp SE, Almfeldt I, Millinger PA (1975) Programmed continuing education in periodontics. Tandlakartidningen 67(22):1293–1298

Armitage GC (1999) Development of a classification system for periodontal diseases and conditions. Ann Periodontol 4(1):1–6

Listgarten MA, Mao R, Robinson PJ (1976) Periodontal probing and the relationship of the probe tip to periodontal tissues. J Periodontol 47(9):511–513

Armitage GC, Svanberg GK, Löe H (1977) Microscopic evaluation of clinical measurements of connective tissue attachment levels. J Clin Periodontol 4(3):173–190

Garnick JJ, Spray JR, Vernino DM, Klawitter JJ (1980) Demonstration of probes in human periodontal pockets. J Periodontol 51(10):563–570

Garnick JJ, Keagle JG, Searle JR, King GE, Thompson WO (1989) Gingival resistance to probing forces. II. The effect of inflammation and pressure on probe displacement in beagle dog gingivitis. J Periodontol 60(9):498–505

Magnusson I, Listgarten MA (1980) Histological evaluation of probing depth following periodontal treatment. J Clin Periodontol 7(1):26–31

Isidor F, Karring T, Attström R (1984) Reproducibility of pocket depth and attachment level measurements when using a flexible splint. J Clin Periodontol 11(10):662–668

Aguero A, Garnick JJ, Keagle J, Steflik DE, Thompson WO (1995) Histological location of a standardized periodontal probe in man. J Periodontol 66(3):184–190

Jeffcoat M (2002) What is clinical significance? J Clin Periodontol 29(Suppl 2):30–32

Harris RJ (2003) Case series untreated periodontal disease: a follow-up on 30 cases case series. J Periodontol 74(5):672–678

Papapanou PN (1989) Patterns of alveolar bone loss in the assessment of periodontal treatment priorities. Swed Dent J Suppl 66:1–45

Mardas N, Kraehenmann M, Dard M (2012) Regenerative wound healing in acute degree III mandibular defects in dogs. Quintessence Int 43(5):e48–e59

Araújo MG, Lindhe J (1998) GTR treatment of degree III furcation defects following application of enamel matrix proteins. An experimental study in dogs. J Clin Periodontol 25(6):524–530

Sallum EA, Pimentel SP, Saldanha JB, Nogueira-filho GR, Casati MZ, Jr FHN et al (2004) Enamel matrix derivative and guided tissue regeneration in the treatment of dehiscence-type defects: a histomorphometric study in dogs. Image (Rochester, NY) 1357–1363

Casarin RCV, Ribeiro EDP, Nociti FH, Sallum AW, Ambrosano GMB, Sallum EA et al (2010) Enamel matrix derivative proteins for the treatment of proximal class II furcation involvements: a prospective 24-month randomized clinical trial. J Clin Periodontol 37(12):1100–1109

Allograft FB, Gurinsky BS, Mills MP, Mellonig JT (2004) Clinical evaluation of demineralized derivative alone for the treatment of periodontal osseous defects in humans. Matrix 1309–1318

Itoh N, Kasai H, Ariyoshi W, Harada E, Yokota M, Mechanisms NT (2006) Mechanisms involved in the enhancement of osteoclast formation by enamel matrix derivative. J Periodontal Res

Schwartz Z, Carnes DL, Pulliam R, Lohmann CH, Sylvia VL, Liu Y et al (2000) Porcine fetal enamel matrix derivative stimulates proliferation but not differentiation of pre-osteoblastic 2T9 cells, inhibits proliferation and stimulates differentiation of osteoblast-like MG63 cells, and increases proliferation and differentiation of normal human osteoblast NHOst cells. J Periodontol 71(8):1287–1296

Koop R, Merheb J, Quirynen M (2012) Periodontal regeneration with enamel matrix derivative in reconstructive periodontal therapy: a systematic review. J Periodontol 83(6):707–720

Houser BE, Mellonig JT, Brunsvold MA, Cochran DL, Meffert RM, Alder ME (2001) Clinical evaluation of anorganic bovine bone xenograft with a bioabsorbable collagen barrier in the treatment of molar furcation defects. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 21(2):161–169

Tsao Y-P, Neiva R, Al-Shammari K, Oh T-J, Wang H-L (2006) Effects of a mineralized human cancellous bone allograft in regeneration of mandibular class II furcation defects. J Periodontol 77(3):416–425

Lekovic V, Kenney EB, Carranza FA, Danilovic V (1990) Treatment of class II furcation defects using porous hydroxylapatite in conjunction with a polytetrafluoroethylene membrane. J Periodontol 61(9):575–578

Carranza FA, Jolkovsky DL (1991) Current status of periodontal therapy for furcation involvements. Dent Clin N Am 35(3):555–570

Anderegg CR, Alexander DC, Freidman M (1999) A bioactive glass particulate in the treatment of molar furcation invasions. J Periodontol 70(4):384–387

Bowers GM, Schallhorn RG, McClain PK, Morrison GM, Morgan R, Reynolds MA (2003) Factors influencing the outcome of regenerative therapy in mandibular class II furcations: part I. J Periodontol 74(9):1255–1268

Trombelli L (2005) Which reconstructive procedures are effective for treating the periodontal intraosseous defect? Periodontol 2000 37:88–105

Reynolds MA, Aichelmann-Reidy ME, Branch-Mays GL, Gunsolley JC (2003) The efficacy of bone replacement grafts in the treatment of periodontal osseous defects. A systematic review. Ann Periodontol 8(1):227–265

Blomlöf J, Lindskog S (1995) Periodontal tissue-vitality after different etching modalities. J Clin Periodontol 22(6):464–468

Blomlöf J, Jansson L, Blomlöf L, Lindskog S (1995) Long-time etching at low pH jeopardizes periodontal healing. J Clin Periodontol 22(6):459–463

Blomlöf J, Jansson L, Blomlöf L, Lindskog S (1996) Root surface etching at neutral pH promotes periodontal healing. J Clin Periodontol 23(1):50–55

Mayfield L, Söderholm G, Norderyd O, Attström R (1998) Root conditioning using EDTA gel as an adjunct to surgical therapy for the treatment of intraosseous periodontal defects. J Clin Periodontol 25(9):707–714

Blomlöf L, Jonsson B, Blomlöf J, Lindskog S (2000) A clinical study of root surface conditioning with an EDTA gel. II. Surgical periodontal treatment. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 20(6):566–573

Sculean A, Berakdar M, Willershausen B, Arweiler NB (2006) Effect of EDTA root conditioning on the healing of intrabony defects treated with an enamel matrix protein derivative. Therapy 1167–1172

Bittencourt S, Ribeiro EDP, Sallum EA, Sallum AW, Nociti FH, Casati MZ (2007) Root surface biomodification with EDTA for the treatment of gingival recession with a semilunar coronally repositioned flap. J Periodontol 78(9):1695–1701

Harrel SK, Nunn ME (2001) Longitudinal comparison of the periodontal status of patients with moderate to severe periodontal disease receiving no treatment, non-surgical treatment, and surgical treatment utilizing individual sites for analysis. J Periodontol 72(11):1509–1519

Hak DJ (2007) The use of osteoconductive bone graft substitutes in orthopaedic trauma. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 15(9):525–536

AlGhamdi AS, Shibly O, Ciancio SG (2010) Osseous grafting part I: autografts and allografts for periodontal regeneration—a literature review. J Int Acad Periodontol 12(2):34–38

AlGhamdi AS, Shibly O, Ciancio SG (2010) Osseous grafting part II: xenografts and alloplasts for periodontal regeneration—a literature review. J Int Acad Periodontol 12(2):39–44

Peres MFS, Ribeiro EDP, Casarin RCV, Ruiz KGS, Junior FHN, Sallum EA et al (2013) Hydroxyapatite/β-tricalcium phosphate and enamel matrix derivative for treatment of proximal class II furcation defects: a randomized clinical trial. J Clin Periodontol 40(3):252–259

Pietruska M, Pietruski J, Nagy K, Brecx M, Arweiler NB, Sculean A (2012) Four-year results following treatment of intrabony periodontal defects with an enamel matrix derivative alone or combined with a biphasic calcium phosphate. Clin Oral Investig 16(4):1191–1197

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Joao Sangiorgio and Dr. Renato Casarin for the assistance with the statistical analysis and suggestions to the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Research involving human participants

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Ethical Committee of the Piracicaba Dental School—University of Campinas—UNICAMP and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in this study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Queiroz, L.A., Santamaria, M.P., Casati, M.Z. et al. Enamel matrix protein derivative and/or synthetic bone substitute for the treatment of mandibular class II buccal furcation defects. A 12-month randomized clinical trial. Clin Oral Invest 20, 1597–1606 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-015-1642-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00784-015-1642-x