Abstract

Purpose

The aim of the present study was to examine the natural history in patients with lumbar spinal stenosis. The incidence of surgery for this condition has increased considerably during the past decades in spite of a fairly favorable natural history in previous studies.

Methods

146 consecutive patients with clinical signs and image findings of lumbar spinal stenosis, who were not recommended surgical treatment, were followed; the reason as to why surgery was not recommended was a moderate symptom level. The follow-up rate was 89% after 3.3 years. Group values for comorbidities and diagnostic imaging were comparable to patients selected for surgery, with the exception of a lower frequency of degenerative spondylolisthesis among the non-operative patients. The mean age of those observed was 68 (21–91), and 58% were females.

Results

During the observation period spontaneous improvements were found for pain and health-related quality of life, but not for walking. Using the minimum clinically important difference for VAS, leg and back pain improved in 32 and 36% of patients, respectively, were unchanged in 55 and 54%, and worsened in 13 and 10%. Findings on diagnostic imaging did not influence patient outcome, except for stenoses with cross-sectional area <0.5 cm2 where spontaneous improvement was not seen. Revision of the decision not to operate occurred in 10 cases (7%).

Conclusions

The natural history of LSS with moderate symptom levels rarely shows symptom deterioration over a median of 3.3 years; in fact, a slight improvement of symptoms was seen at group levels. The treatment decision was revised for 7%, and for the rest an increase in pain was seen in 10–13%. The results support reluctance towards surgery, if the symptom levels are tolerable for the patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lumbar spinal stenosis (LSS) is, together with lumbar disk herniation, the most common specific disorder causing lower back pain and radiating leg problems [1]. The incidence in Sweden was reported to be 5 per 100,000 annually in the 1980s [2]. According to a national register study [3], the annual rate of surgery increased threefold in Sweden between 1987 and 1999. Increasing numbers of surgical procedures for spinal stenosis have also been reported from the United States [4]. According to data from the National Swedish Spine Register, the number of surgeries for LSS (central spinal stenosis) in Sweden during 2013 was 3834 [5]. With the population of Sweden at the end of that year standing at 9.6 million, the incidence of surgeries for LSS amounts to 40 per 100,000—thus, a marked increase in the rate of surgery for this condition is well established. Reasons for this may include factors such as increased knowledge of the condition, increased availability to diagnostic imaging, and/or increased demands on the activity from patients. Although good results from decompression surgery are well established, health care providers should also be aware of the natural history in the studies that exist, where rather favorable results without surgical treatment are described.

Johnsson followed 32 such patients and found symptoms to be unchanged in 70%, improved in 15%, and worse in 15% [6]. In a randomized controlled trial of surgical versus non-surgical treatment all patients improved, and though surgery was superior to non-surgical treatment the effect diminished with time after 2 years [7]. The same was noted for some symptoms in the Maine lumbar spine study; the relative benefits of surgery for low back pain, predominant symptom relief, and satisfaction with current state, found at 1 and 4 years were no longer present at 8–10 years although leg pain relief and back-specific function still favored surgical treatment [8]. Deteriorating results over time have also been reported by others [9, 10]. Interpretation of long-term outcome after comparative studies on surgical versus non-operative treatments is problematic since cross-overs are difficult to avoid and outcomes tend to converge over time [4, 7, 8].

Comorbidities are common in this group of elderly patients, and identifying them is an essential factor in the evaluation of function and operability in patients with LSS; especially as they have also been shown to influence the results after surgical treatment [11,12,13,14]. In order to provide the best possible advice regarding treatment of patients with LSS, a deeper knowledge of the natural history is needed. Identifying potential factors or symptom characteristics for good or bad prognoses would also help surgeons in the shared decision-making process with patients about surgery [15].

Objectives

The purpose of the present study was to perform a prospective follow-up of a population of patients with neurogenic claudication and diagnostic imaging demonstrating central LSS, who did not receive surgical treatment. A further aim was to study factors potentially influencing the natural history in such a population.

Materials and methods

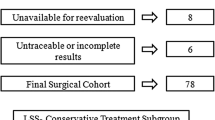

Two hundred and thirty-eight patients with LSS, consecutively collected from a computerized data interview from 1999 to 2001, were primarily included. Baseline data from all patients were collected routinely by way of the computerized interview system [16]; review of all medical records was performed, collecting information on comorbidities and reported imaging findings. LSS was defined as findings of central spinal stenosis with dural sac area (DSA) of <1.0 cm2 on cross-sectional images from magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computer tomography (CT), in association with typical clinical symptoms (neurogenic claudication and/or radiating leg pain). The localization of the vertebral level of the stenosis, the number of affected levels and dural sac area (DSA), and the presence of degenerative spondylolisthesis or degenerative scoliosis (Cobb angle >10°) were registered from radiological reports. Cases with isolated lateral (recess or foraminal) lumbar spinal stenosis only and isthmic spondylolisthesis were excluded. Previous lumbar surgery, with the exception of discectomy more than 2 years earlier, was also included in the exclusion criteria. In some analyses, the DSA was divided into severe and less severe stenosis, with the cut-off arbitrarily set at 0.5 cm2.

Comorbidities were quantified according to Davies [17], evaluated across seven domains: malignancy, ischemic heart disease, peripheral vascular disease, left ventricular dysfunction, diabetes mellitus, systemic collagen vascular disease, and other significant pathology. The comorbidity score for each patient is the number of domains affected, giving a theoretical maximum of 7. Grade 0 (low risk) is a zero score, grade 1 (medium risk) is a score of 1–2, and grade 2 (high risk) is a cumulative score of >3.

A computerized interview was performed in the hospital during the first evaluation visit. This validated system employs a touchscreen for the input of data [16]. Collected data included age, gender, intensity of leg and back pain using a visual analog scale (VAS) of 0–100 [18, 19], walking distance in four categories (<100 m, 100–500 m, 500 m–1 km, and >1 km), health-related quality of life (HRQL) monitored by the Short Form 36 survey (SF-36) and Euroqol (EQ 5D) [20,21,22], and depressive symptoms using the Zung depression scale (ZDS) [23]. SF-36 values from a Swedish age-matched general population were used for comparative demonstrations [24]. The minimum clinically important difference for VAS used in some analyses was defined according to Hagg [25].

146 patients were, in a shared decision-making process, not scheduled for surgery because the symptom levels were moderate and did not justify surgical treatment. This population was followed in order to study the natural history of LSS (with moderate symptoms). Comparisons with those who were scheduled for surgery (n = 92) were made, validating that the natural history group had the same baseline characteristics.

A paper-based questionnaire with identical sets of data was mailed to the patients in the natural history population for follow-up. At this time, 120 patients were eligible. 14 were deceased, 2 were mentally disabled, and 10 had been scheduled for surgery for LSS during the follow-up period. The cases scheduled for surgery during the follow-up period were comparable concerning age and sex, and had a somewhat higher degree of comorbidity and more affected levels compared to the rest of the natural history cohort. They also had a degree of slip comparable to that of the surgical cohort. Answers were received from 107 patients, a response rate of 89%. The follow-up was performed at a certain point in time, with primary visits spread out over approximately 2.5 years, giving varying follow-up times with a median of 3.3 years (2.1–5.1).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the statistical package for social sciences (SPSS).

Numerical data were compared with t tests. Where paired data were available, paired t tests were used. Nominal scale variables were compared with the χ 2 test or Wilcoxon signed-rank test (paired data).

Results

146 patients were included in the natural history cohort; 58% female with a mean age of 70 years (21–91), and 42% male with a mean age of 67 years (31–87). Baseline characteristics showed a mean intensity of leg pain (VAS) of 57 and a mean intensity of back pain (VAS) of 61. Walking ability was <500 m in 56%. Mean EQ-5D was 38. The mean score for ZDS was 41. Comorbidity according to Davis was grade 0 in 41%, grade 1 in 51%, and grade 2 in 8% with a mean grade of 0.66. 53% had one stenotic level, 33% had two levels, and 14% had three levels or more, with a mean of 1.63 stenotic levels per case. Mean DSA at the most stenotic levels was 0.50 cm2. Degenerative scoliosis was present in 26% and degenerative spondylolisthesis in 26% (Table 1). The most frequent levels affected by LSS were L3–L4 and L4–L5 (Fig. 1).

The baseline values differed from those of the group of patients selected for surgery in that, for the surgical cases, VAS levels for leg and back pain were higher: 73 and 70 respectively, compared to 57 and 61. Walking ability was less with 81% not able to walk 500 m; the rate of degenerative spondylolisthesis was also 37% in the surgery group, compared to 26% in the non-operative group (Table 1). HRQL described by SF-36 domains showed lower values in the physical function domains (PF and RF) and bodily pain (BP) for the patients scheduled for surgery. Apart from these differences, the natural history cohort was comparable to the group of patients selected for surgery (Table 1; Fig. 2).

SF-36 domains of patients with LSS comparing the natural history cohort to the surgical cases. For comparison, age-matched normal controls of a Swedish population are shown. PF physical functioning, RP physical role functioning, BP bodily pain, GH general health perceptions, VT vitality, SF social role functioning, RE emotional role functioning, MH mental health. Statistics by t test

Among the questionnaire follow-ups of the natural history cohort, improved VAS levels of pain were noted, with a mean leg pain of 47 and back pain of 52. HRQL also improved to a mean EQ-5D of 49. There was no difference in the proportion of patients with walking ability <500 m. ZDS showed a slightly higher value at follow-up (Table 2). Comparing HRQL measured by SF-36 at baseline and follow-up, there was a significant increase in the domains representing physical function (PF and RP) and pain (BP). There were no changes in the other domains (GH, VT, RE, MH) (Fig. 3).

SF-36 domains of patients with LSS comparing the baseline values to the follow-up values of the natural history cohort. PF physical functioning, RP physical role functioning, BP bodily pain, GH general health perceptions, VT vitality, SF social role functioning, RE emotional role functioning, MH mental health. Statistics by t test

At an individual level, using the minimum clinically important difference (MCID) for VAS (±20 units), leg and back pain were unchanged at follow-up in 55 and 54% respectively, improved in 32 and 36%, and worse in 13 and 10%. Thus leg and back pain were unchanged or improved clinically at follow-up in 87 and 90%, respectively in the natural history group (Figs. 4, 5). Walking distance categories were unchanged in 49%, improved in 29%, and worse in 22% (Fig. 6).

Comparing radiological and clinical data, we found that spinal stenosis patients with lumbar degenerative scoliosis had significantly more back pain and lower HRQL (EQ-5D) at baseline and follow-up, compared to those without. Presence of degenerative spondylolisthesis, degree of stenosis, or number of stenotic levels in the lumbar spine did not influence clinical symptoms or HRQL at baseline or follow-up (Table 3). In cases of high-grade spinal stenosis (DSA <0.5 cm2), the improvement in pain and HRQL otherwise noted over the natural course of the condition was not present. Degenerative spondylolisthesis, degenerative scoliosis, or multi-level spinal stenosis did not affect the natural course of the condition as reflected by the differences in values from baseline to follow-up (Table 3).

Discussion

Symptomatic degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis is a common reason for lumbar spine surgery, and the incidence of surgery has been shown to increase over time [3,4,5]. The natural history of the condition has been the subject of some studies [6, 26, 27] and has generally been described as good. In spite of this, the incidence of spinal stenosis surgery continues to increase [5].

This study was performed in order to further describe the natural history of this condition focusing on our patient population. The aim was also supported by the scarce literature on the subject and the importance of knowledge of natural history in counseling patients [8, 15]. The cohort followed comprised patients who were referred to a spinal surgery unit for LSS but also who subsequently were not scheduled for surgical treatment. This in turn was the result of a shared decision-making process between the surgeon and the patient based on symptom levels of neurogenic claudication and pain.

Limitations of the study were that a mix of CT and MRI examinations were used at the time; some cases may have received non-operative treatment measures, and others not, and this was not monitored. Strengths were the prospectivity in data collection and a high follow-up rate (89%).

To analyze differences between populations with symptomatic LSS, with and without the indication for surgery, baseline data from questionnaires and medical records were collected for all patients with LSS consecutively examined at the spinal surgery unit during a 3-year period. The two populations were comparable concerning age, sex, depressive symptoms, HRQL, and comorbidities (Table 1; Fig. 2). The populations also had the same findings on diagnostic imaging concerning lumbar degenerative scoliosis, dural sac area, and distribution segments involved (Table 1; Fig. 2).

The patients selected for surgery had—as expected—a higher pain level, shorter walking distance, and lower physical function. They also had a somewhat higher rate of degenerative spondylolisthesis (Table 1) although this did not influence clinical symptoms (Table 3). Despite this we found it reasonable to use this non-operative population with moderate but typical symptoms of LSS and follow them with identical questionnaires as were used at baseline, in order to study development over time describing the natural history.

The studied natural history population included cases with degenerative spondylolisthesis, as well as with degenerative lumbar scoliosis. These findings may imply differences in symptomatology [28], but since they are common findings in the cohorts of patients with LSS we have chosen to include them in order to study their potential influence on the natural history.

The results of the study showed that the natural history of LSS with moderate symptoms was good. This is supported by the fact that the proportion of patients who reported unchanged symptoms or improvement during the follow-up was high. Roughly one-third of the patients reported improvement of pain and walking ability, with half of the patients unchanged. Worsening was noted in 10–13% for pain levels and 22% for walking ability (Figs. 4, 5, 6). Mean values for the whole study were improved in all studied respects except for walking (Table 2; Fig. 3). The decision not to treat surgically was revised in 10 of the 146 cases (7%). This is a low rate of cross-over and as such a low failure rate of a non-operative regime although a higher figure would be the result if one were to include the patients experiencing deterioration of symptoms. Also supporting an initial non-operative attitude is a recent study by Zweig et al. [29] which showed that the duration of pre-operative conservative treatment was not associated with the ultimate outcome of decompression surgery. Thus, recommending conservative treatment due to moderate symptom levels could be done safely, with little risk of deterioration and a good outcome should surgery be needed at a later stage.

We also studied the relationship between findings on diagnostic imaging and clinical symptoms and could not observe that a high degree of stenosis, a multi-level involvement, or a degenerative spondylolisthesis corresponded to higher pain levels or worse HRQL. Presence of degenerative scoliosis in the lumbar spine, however, did correspond to more back pain and lower HRQL at baseline and follow-up (Table 3). This implies that the co-presence of a degenerative scoliosis of the lumbar spine constitutes a different pathology from LSS, with different symptom characteristics (more back pain and lower HRQL), that warrants other considerations in surgical evaluation. Finally, we also studied the predictive value of findings on diagnostic imaging on the natural history. Neither degenerative spondylolisthesis, degenerative scoliosis, nor the number of stenotic levels influenced the natural history but we found that the spontaneous improvement in VAS values, otherwise noted, was present in patients with DSA ≥0.5 cm2 but not if DSA was <0.5 cm2 (Table 3). A very tight LSS thus predicts absence of spontaneous improvement and may be used as a factor in favor of surgical treatment.

Conclusions

The natural history in LSS from other studies is confirmed. Since worsening of pain and walking capacity are rare, reluctance towards surgery in patients with tolerable symptom levels is warranted. Presence of a degenerative lumbar scoliotic deformity implies a partially different pathology with higher symptom levels. Findings on diagnostic imaging do not influence the clinical development over time, except for patients with a very narrow dural sac area (<0.5 cm2) where spontaneous improvement is not to be expected.

References

Verbiest H (1954) A radicular syndrome from developmental narrowing of the lumbar vertebral canal. J Bone Jt Surg Br 36-B(2):230–237

Johnsson KE (1995) Lumbar spinal stenosis. A retrospective study of 163 cases in southern Sweden. Acta Orthop Scand 66(5):403–405

Jansson KA, Blomqvist P, Granath F, Nemeth G (2003) Spinal stenosis surgery in Sweden 1987–1999. Eur Spine J 12(5):535–541. doi:10.1007/s00586-003-0544-9

Atlas SJ, Keller RB, Robson D, Deyo RA, Singer DE (2000) Surgical and nonsurgical management of lumbar spinal stenosis: 4-year outcomes from the maine lumbar spine study. Spine 25(5):556–562

Stromqvist B, Fritzell P, Hagg O, Knutsson B, Sandén B (2014) Swespine, the swedish spine register. Annual register report 2014. http://www.swespine.se. Accessed 30 Nov 2016

Johnsson KE, Rosen I, Uden A (1992) The natural course of lumbar spinal stenosis. Clin Orthop Relat Res 279:82–86

Malmivaara A, Slatis P, Heliovaara M, Sainio P, Kinnunen H, Kankare J, Dalin-Hirvonen N, Seitsalo S, Herno A, Kortekangas P, Niinimaki T, Ronty H, Tallroth K, Turunen V, Knekt P, Harkanen T, Hurri H (2007) Surgical or nonoperative treatment for lumbar spinal stenosis? A randomized controlled trial. Spine 32(1):1–8. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000251014.81875.6d

Atlas SJ, Keller RB, Wu YA, Deyo RA, Singer DE (2005) Long-term outcomes of surgical and nonsurgical management of lumbar spinal stenosis: 8–10 year results from the maine lumbar spine study. Spine 30(8):936–943

Amundsen T, Weber H, Nordal HJ, Magnaes B, Abdelnoor M, Lilleas F (2000) Lumbar spinal stenosis: conservative or surgical management? A prospective 10-year study. Spine 25(11):1424–1435 (discussion 1435–1426)

Chang Y, Singer DE, Wu YA, Keller RB, Atlas SJ (2005) The effect of surgical and nonsurgical treatment on longitudinal outcomes of lumbar spinal stenosis over 10 years. J Am Geriatr Soc 53(5):785–792. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53254.x

Arinzon ZH, Fredman B, Zohar E, Shabat S, Feldman JS, Jedeikin R, Gepstein RJ (2003) Surgical management of spinal stenosis: a comparison of immediate and long term outcome in two geriatric patient populations. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 36(3):273–279

Cassinelli EH, Eubanks J, Vogt M, Furey C, Yoo J, Bohlman HH (2007) Risk factors for the development of perioperative complications in elderly patients undergoing lumbar decompression and arthrodesis for spinal stenosis: an analysis of 166 patients. Spine 32(2):230–235. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000251918.19508.b3

Katz JN, Stucki G, Lipson SJ, Fossel AH, Grobler LJ, Weinstein JN (1999) Predictors of surgical outcome in degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis. Spine 24(21):2229–2233

Slover J, Abdu WA, Hanscom B, Weinstein JN (2006) The impact of comorbidities on the change in short-form 36 and oswestry scores following lumbar spine surgery. Spine 31(17):1974–1980. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000229252.30903.b9

Kurd MF, Lurie JD, Zhao W, Tosteson T, Hilibrand AS, Rihn J, Albert TJ, Weinstein JN (2012) Predictors of treatment choice in lumbar spinal stenosis: a spine patient outcomes research trial study. Spine 37(19):1702–1707. doi:10.1097/BRS.0b013e3182541955

Frennered K, Hagg O, Wessberg P (2010) Validity of a computer touch-screen questionnaire system in back patients. Spine 35(6):697–703. doi:10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181b43a20

Davies SJ, Russell L, Bryan J, Phillips L, Russell GI (1995) Comorbidity, urea kinetics, and appetite in continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis patients: their interrelationship and prediction of survival. Am J Kidney Dis 26(2):353–361

Carlsson AM (1983) Assessment of chronic pain. I. Aspects of the reliability and validity of the visual analogue scale. Pain 16(1):87–101

Jensen MP, Karoly P (1992) Selfreported scales and procedures for assessing pain in adults. In: Turk DC, Melzack R (eds) Handbook of pain assessment. Guilford Press, New York, pp 15–34

The EuroQol Group (1990) EuroQol—a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy 16(3):199–208

McHorney CA, Ware JE Jr, Raczek AE (1993) The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): II. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Med Care 31(3):247–263

Ware JE Jr, Sherbourne CD (1992) The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care 30(6):473–483

Zung WW (1965) A self-rating depression scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry 12:63–70

Sullivan M, Karlsson J, Taft C, Ware JE (2002) The Swedish SF-36 Health Survey. Swedish Manual and Interpretation Guide, Second edn. Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Gothenburg

Hagg O, Fritzell P, Nordwall A (2003) The clinical importance of changes in outcome scores after treatment for chronic low back pain. Eur Spine J 12(1):12–20. doi:10.1007/s00586-002-0464-0

Benoist M (2002) The natural history of lumbar degenerative spinal stenosis. Jt Bone Spine (revue du rhumatisme) 69(5):450–457

Johnsson KE, Uden A, Rosen I (1991) The effect of decompression on the natural course of spinal stenosis. A comparison of surgically treated and untreated patients. Spine 16(6):615–619

Pearson A, Blood E, Lurie J, Tosteson T, Abdu WA, Hillibrand A, Bridwell K, Weinstein J (2010) Degenerative spondylolisthesis versus spinal stenosis: does a slip matter? Comparison of baseline characteristics and outcomes (SPORT). Spine 35(3):298–305. doi:10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181bdafd1

Zweig T, Enke J, Mannion AF, Sobottke R, Melloh M, Freeman BJ, Aghayev E, Spine Tango C (2017) Is the duration of pre-operative conservative treatment associated with the clinical outcome following surgical decompression for lumbar spinal stenosis? A study based on the Spine Tango Registry. Eur Spine J 26(2):488–500. doi:10.1007/s00586-016-4882-9

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Wessberg, P., Frennered, K. Central lumbar spinal stenosis: natural history of non-surgical patients. Eur Spine J 26, 2536–2542 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-017-5075-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-017-5075-x