Abstract

We propose a management strategy for acute cholangitis and cholecystitis according to the severity assessment. For Grade I (mild) acute cholangitis, initial medical treatment including the use of antimicrobial agents may be sufficient for most cases. For non-responders to initial medical treatment, biliary drainage should be considered. For Grade II (moderate) acute cholangitis, early biliary drainage should be performed along with the administration of antibiotics. For Grade III (severe) acute cholangitis, appropriate organ support is required. After hemodynamic stabilization has been achieved, urgent endoscopic or percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage should be performed. In patients with Grade II (moderate) and Grade III (severe) acute cholangitis, treatment for the underlying etiology including endoscopic, percutaneous, or surgical treatment should be performed after the patient’s general condition has been improved. In patients with Grade I (mild) acute cholangitis, treatment for etiology such as endoscopic sphincterotomy for choledocholithiasis might be performed simultaneously, if possible, with biliary drainage. Early laparoscopic cholecystectomy is the first-line treatment in patients with Grade I (mild) acute cholecystitis while in patients with Grade II (moderate) acute cholecystitis, delayed/elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy after initial medical treatment with antimicrobial agent is the first-line treatment. In non-responders to initial medical treatment, gallbladder drainage should be considered. In patients with Grade III (severe) acute cholecystitis, appropriate organ support in addition to initial medical treatment is necessary. Urgent or early gallbladder drainage is recommended. Elective cholecystectomy can be performed after the improvement of the acute inflammatory process.

Free full-text articles and a mobile application of TG13 are available via http://www.jshbps.jp/en/guideline/tg13.html.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

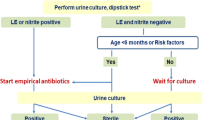

This article describes strategies for the management of acute cholangitis and cholecystitis including initial medical treatment flowcharts. We established a flowchart for the diagnosis and treatment of acute cholangitis and cholecystitis as reported in the Tokyo Guidelines 2007 [1]. Flowcharts for the management of acute cholangitis and cholecystitis have been revised in the updated Tokyo Guidelines (TG13).

We consider that the primary purpose of the flowcharts is to allow clinicians to grasp, at a glance, the outline of the management strategy of the disease. Flowcharts have been colored for easy access and rapid understanding, and most of the treatment methods are included in the flowcharts to achieve their primary purpose.

General guidance for the management of acute cholangitis

The general guidance for the management of acute biliary inflammation/infection including acute cholangitis is presented in Fig. 1.

Clinical presentations

Clinical findings associated with acute cholangitis include abdominal pain, jaundice, fever (Charcot’s triad), and rigor. The triad was reported in 1887 by Charcot [2] as the indicators of hepatic fever and has been historically used as the generally accepted clinical findings of acute cholangitis. All three symptoms are observed in about 50–70 % of the patients with acute cholangitis [3–6]. Reynolds’ pentad––Charcot’s triad plus shock and decreased level of consciousness––were presented in 1959 when Reynolds and Dargan [7] defined acute obstructive cholangitis. Reynolds’ pentad is often referred to as the findings representing serious conditions, but shock and a decreased level of consciousness are only observed in less than 30 % of patients with acute cholangitis [3–6]. A history of biliary diseases such as gallstones, previous biliary procedures, or the placement of a biliary stent is very helpful when a diagnosis of acute cholangitis is suspected [1].

Blood test

The diagnosis of acute cholangitis requires the measurement of white blood cell count, C-reactive protein, and liver function test including alkaline phosphatase, GGT, AST, ALT, and bilirubin [8]. The assessment of the severity of the illness requires knowledge of the platelet count, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, prothrombin time-international normalized ratio (PT-INR), albumin, and arterial blood gas analysis. Blood cultures are also helpful for selection of antimicrobial drugs [8–10]. Hyperamylasemia is a useful parameter for identifying complications such as choledocholithiasis causing biliary pancreatitis [11].

Diagnostic imaging

Abdominal ultrasound (US) and abdominal computerized tomography (CT) with intravenous contrast are very useful test procedures for evaluating patients with acute biliary tract disease. Abdominal US should be performed in all patients with suspected acute biliary inflammation/infection [1]. Ultrasonic examination has satisfactory diagnostic capabilities when performed not only by specialists but also by emergency physicians [12, 13]. The role of diagnostic imaging in acute cholangitis is to determine the presence of biliary obstruction, the level of obstruction, and the cause of the obstruction such as gallstones and/or biliary strictures [1]. The assessment should include US and CT. These studies complement each other and CT may yield better imaging of bile duct dilatation and pneumobilia.

Differential diagnosis

Diseases which should be differentiated from acute cholangitis are acute cholecystitis, liver abscess, gastric and duodenal ulcer, acute pancreatitis, acute hepatitis, and septicemia from other origins.

Q1. What is the initial medical treatment of acute cholangitis?

Early treatment, while fasting as a rule, includes sufficient infusion, the administration of antimicrobial and analgesic agents, along with the monitoring of respiratory hemodynamic conditions in preparation for emergency drainage [1].

When acute cholangitis has become more severe, that is, if any one of the following signs is observed such as shock (reduced blood pressure), consciousness disturbance, acute lung injury, acute renal injury, hepatic injury, and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) (decreased platelet count), emergency biliary drainage is carried out together with appropriate organ support (sufficient infusion and anti-microbial administration), and respiratory and circulatory management (artificial respiration, intubation, and use of vasopressors) [1].

Q2. Should the severe sepsis bundle be referred to for the early treatment of acute cholangitis accompanying severe sepsis?

Acute cholangitis is frequently accompanied by sepsis. As for the early treatment of severe sepsis, there is a detailed description in “Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines (SSCG)” published in 2004 and updated in 2008. To improve treatment results, a severe sepsis bundle (Table 1, http://www.ihi.org/knowledge/Pages/Changes/ImplementEffectiveGlucoseControl.aspx) has been presented in SSCG as the core part of the treatment for septic shock. However, there are reports of validation by several multi-institutional collaborative studies that have found a significant decrease in mortality rate in patients with a higher rate of compliance [14] or after the implementation of the severe sepsis bundle [15–17]. These studies include severe sepsis cases induced by a disease other than acute cholangitis [14–17]. However, the severe sepsis bundle should be referred to for the early treatment of acute cholangitis accompanying severe sepsis.

Flowchart for the management of acute cholangitis

A flowchart for the management of acute cholangitis is shown in Fig. 2. Treatment of acute cholangitis should be performed according to the severity grade of the patient. Biliary drainage and antimicrobial therapy are the two most important elements of treatment. When a diagnosis of acute cholangitis is determined based on the diagnostic criteria of acute cholangitis of TG13 [9], initial medical treatment including nil per os (NPO), intravenous fluid, antimicrobial therapy, and analgesia together with close monitoring of blood pressure, pulse, and urinary output should be initiated. Simultaneously, severity assessment of acute cholangitis should be conducted based on the severity assessment criteria for acute cholangitis of TG 13 [9] in which acute cholangitis is classified into Grade I (mild), Grade II (moderate), or Grade III (severe). Frequent reassessment is mandatory and patients may need to be re-classified into Grade I, II, or III based on the response to initial medical treatment. Appropriate treatment should be performed in accordance with the severity grade. Patients with acute cholangitis sometimes suffer simultaneously from acute cholecystitis. A treatment strategy for patients with both acute cholangitis and cholecystitis should be determined in consideration of the severity of those diseases and the surgical risk in patients.

Grade I (mild) acute cholangitis

Initial medical treatment including antimicrobial therapy may be sufficient. Biliary drainage is not required for most cases. However, for non-responders to initial medical treatment, biliary drainage should be considered. Endoscopic, percutaneous, or operative intervention for the etiology of acute cholangitis such as choledocholithiasis and pancreato-biliary malignancy may be performed after pre-intervention work-up. Treatment for etiology such as endoscopic sphincterotomy for choledocholithiasis might be performed simultaneously, if possible, with biliary drainage. Some patients who have developed postoperative cholangitis may require antimicrobial therapy only and generally do not require intervention.

Grade II (moderate) acute cholangitis

Early endoscopic or percutaneous drainage, or even emergency operative drainage with a T-tube, should be performed in patients with Grade II acute cholangitis. A definitive procedure should be performed to remove a cause of acute cholangitis after the patient’s general condition has improved and following pre-intervention work-up.

Grade III (severe) acute cholangitis

Patients with acute cholangitis accompanied by organ failure are classified as Grade III (severe) acute cholangitis. These patients require appropriate organ support such as ventilatory/circulatory management (non-invasive/invasive positive pressure ventilation and use of vasopressor, etc.). Urgent biliary drainage should be anticipated. When patients are stabilized with initial medical treatment and organ support, urgent (as soon as possible) endoscopic or percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage or, according to the circumstances, an emergency operation with decompression of the bile duct with a T-tube should be performed. Definitive treatment for the cause of acute cholangitis including endoscopic, percutaneous, or operative intervention should be considered once the acute illness has resolved.

General guidance for the management of acute cholecystitis

The general guidance for the management of acute biliary inflammation/infection including acute cholecystitis is presented in Fig. 1.

Clinical presentations

Clinical symptoms of acute cholecystitis include abdominal pain (right upper abdominal pain), nausea, vomiting, and pyrexia [18–20]. The most typical symptom is right epigastric pain. Tenderness in the right upper abdomen, a palpable gallbladder, and Murphy’s sign are the characteristic findings of acute cholecystitis. A positive Murphy’s sign shows 79–96 % specificity [18, 20] for acute cholecystitis.

Blood test

There is no specific blood test for acute cholecystitis; however, the measurement of white blood cell count and C-reactive protein is very useful in confirming an inflammatory response [21]. The platelet count, bilirubin, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, prothrombin time-international normalized ratio (PT-INR), and arterial blood gas analysis are useful in assessing the severity status of the patient [21].

Diagnostic imaging

Abdominal ultrasound (US) and abdominal computerized tomography (CT) with intravenous contrast are very helpful procedures for evaluating patients with acute biliary tract disease. Abdominal US should be performed in every patient with suspected acute biliary inflammation/infection [1]. Ultrasonic examination has satisfactory diagnostic capability when it is performed not only by specialists but also by emergency physicians [12, 13]. Characteristic findings of acute cholecystitis include the enlarged gallbladder, thickened gallbladder wall, gallbladder stones and/or debris in the gallbladder, sonographic Murphy’s sign, pericholecystic fluid, and pericholecystic abscess [21]. Sonographic Murphy’s sign is a reliable finding of acute cholecystitis showing about 90 % sensitivity and specificity [22, 23], which is higher than those of Murphy’s sign.

Differential diagnosis

Diseases which should be differentiated from acute cholecystitis are gastric and duodenal ulcer, hepatitis, pancreatitis, gallbladder cancer, hepatic abscess, Fitz-Hugh–Curtis syndrome, right lower lobar pneumonia, angina pectoris, myocardial infarction, and urinary infection.

Q3. What is the initial medical treatment of acute cholecystitis?

Early treatment, with fasting as a rule, includes sufficient infusion, the administration of antimicrobial and analgesic agents, along with the monitoring of respiratory hemodynamics in preparation for emergency surgery and drainage [1].

When any one of the following morbidities is observed: further aggravation of acute cholecystitis, shock (reduced blood pressure), consciousness disturbance, acute respiratory injury, acute renal injury, hepatic injury, and DIC (reduced platelet count), then appropriate organ support (sufficient infusion and antimicrobial administration), and respiratory and circulatory management (artificial respiration, intubation, and use of vasopressors) are carried out together with emergency drainage or cholecystectomy [1].

There are many reports showing that remission can be achieved by conservative treatment only [24–26]. On the other hand, there is a report demonstrating that mild cases may not require antimicrobial agents; however, prophylactic administration should take place due to possible complications such as bacterial infection. Furthermore, there is a report that was unable to detect a difference in the positive rate of sonographic Murphy’s sign depending on the presence or absence of the use of analgesic agents [27]. The administration of analgesic agents should therefore be initiated in the early stage.

CQ4. Is the administration of NSAID for the attack of impacted stones gallstone attack effective for preventing acute cholecystitis?

Administration of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for gallstone attack is effective in preventing acute cholecystitis, and they are also widely known as analgesic agents. A NSAID such as diclofenac is thus used for early treatment. According to a report of a double blind randomized controlled trial (RCT) that compared the use of NSAIDs (diclofenac 75 mg intramuscular injection) with placebo [28] or hyoscine 20 mg intramuscular injection [29] for cases of impacted gallstone attack, NSAIDs prevented progression of the disease to acute cholecystitis and also reduced pain. Although NSAIDs have been effective for the improvement of gallbladder function in cases with chronic cholecystitis, there is no report showing that the administration of NSAIDs has contributed to improving the course of cholecystitis after its acute onset [30].

Flowchart for the management of acute cholecystitis

A flowchart for the management of acute cholecystitis is shown in Fig. 3. The first-line treatment of acute cholecystitis is early or urgent cholecystectomy, with laparoscopic cholecystectomy as a preferred method. In high-risk patients, gallbladder drainage such as percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder drainage (PTGBD), percutaneous transhepatic gallbladder aspiration (PTGBA), and endoscopic nasobiliary gallbladder drainage (ENGBD) is an alternative therapy in patients who cannot safely undergo urgent/early cholecystectomy [31, 32]. When a diagnosis of acute cholecystitis is determined based on the diagnostic criteria of acute cholecystitis in TG13 [33], initial medical treatment including NPO, intravenous fluids, antibiotics, and analgesia, together with close monitoring of blood pressure, pulse, and urinary output should be initiated. Simultaneously, severity assessment of acute cholecystitis should be conducted based on the severity assessment criteria for the acute cholecystitis of TG13 [33], in which acute cholecystitis is classified into Grade I (mild), Grade II (moderate), or Grade III (severe). Assessment of the operative risk for comorbidities and the patient’s general status should also be evaluated in addition to the severity grade.

After resolution of acute inflammation with medical treatment and gallbladder drainage, it is desirable that cholecystectomy is performed to prevent recurrence. In surgically high-risk patients with cholecystolithiasis, medical support after percutaneous cholecystolithotomy should be considered [34–36]. In patients with acalculous cholecystitis, cholecystectomy is not always required since recurrence of acute acalculous cholecystitis after gallbladder drainage is rare [31, 37].

Grade I (mild) acute cholecystitis

Early laparoscopic cholecystectomy is the first-line treatment. In patients with surgical risk, observation (follow-up without cholecystectomy) after improvement with initial medical treatment could be indicated.

Grade II (moderate) acute cholecystitis

Grade II (moderate) acute cholecystitis is often accompanied by severe local inflammation. Therefore, surgeons should take the difficulty of cholecystectomy into consideration in selecting a treatment method. Elective cholecystectomy after the improvement of the acute inflammatory process is the first-line treatment. If a patient does not respond to initial medical treatment, urgent or early gallbladder drainage is required. Early laparoscopic cholecystectomy could be indicated if advanced laparoscopic techniques are available. Grade II (moderate) acute cholecystitis with serious local complications is an indication for urgent cholecystectomy and drainage.

Grade III (severe) acute cholecystitis

Grade III (severe) acute cholecystitis is accompanied by organ dysfunction. Appropriate organ support such as ventilatory/circulatory management (noninvasive/invasive positive pressure ventilation and use of vasopressors, etc.) in addition to initial medical treatment is necessary. Urgent or early gallbladder drainage should be performed. Elective cholecystectomy may be performed after the improvement of acute illness has been achieved by gallbladder drainage.

References

Miura F, Takada T, Kawarada Y, Nimura Y, Wada K, Hirota M, et al. Flowcharts for the diagnosis and treatment of acute cholangitis and cholecystitis: Tokyo Guidelines. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2007;14:27–34. (clinical practice guidelines: CPGs).

Charcot M. De la fievre hepatique symptomatique—comparaison avec la fievre uroseptique. Paris: Bourneville et Sevestre; 1877.

Boey JH, Way LW. Acute cholangitis. Ann Surg. 1980;191:264–70.

Csendes A, Diaz JC, Burdiles P, Maluenda F, Morales E. Risk factors and classification of acute suppurative cholangitis. Br J Surg. 1992;79:655–8.

Welch JP, Donaldson GA. The urgency of diagnosis and surgical treatment of acute suppurative cholangitis. Am J Surg. 1976;131:527–32.

O’Connor MJ, Schwartz ML, McQuarrie DG, Sumer HW. Acute bacterial cholangitis: an analysis of clinical manifestation. Arch Surg. 1982;117:437–41.

Reynolds BM, Dargan EL. Acute obstructive cholangitis; a distinct clinical syndrome. Ann Surg. 1959;150:299–303.

Wada K, Takada T, Kawarada Y, Nimura Y, Miura F, Yoshida M, et al. Diagnostic criteria and severity assessment of acute cholangitis: Tokyo Guidelines. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2007;14:52–8. (clinical practice guidelines: CPGs).

Kiriyama S, Takada T, Strasberg SM, Solomkin JS, Mayumi T, Pitt HA, et al. New diagnostic criteria and severity assessment of acute cholangitis in revised Tokyo guidelines. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2012;19:548–56.

Tsuyuguchi T, Sugiyama H, Sakai Y, Nishikawa T, Yokosuka O, Mayumi T, et al. Prognostic factors of acute cholangitis in cases managed using the Tokyo Guidelines. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2012;19:557–65.

Abboud PA, Malet PF, Berlin JA, Staroscik R, Cabana MD, Clarke JR, et al. Predictors of common bile duct stones prior to cholecystectomy: a meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44:450–5.

Rosen CL, Brown DF, Chang Y, Moore C, Averill NJ, Arkoff LJ, et al. Ultrasonography by emergency physicians in patients with suspected cholecystitis. Am J Emerg Med. 2001;19:32–6.

Kendall JL, Shimp RJ. Performance and interpretation of focused right upper quadrant ultrasound by emergency physicians. J Emerg Med. 2001;21:7–13.

Levy MM, Dellinger RP, Townsend SR, Linde-Zwirble WT, Marshall JC, Bion J, et al. The Surviving Sepsis Campaign: results of an international guideline-based performance improvement program targeting severe sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:367–74.

Ferrer R, Artigas A, Levy MM, Blanco J, Gonzalez-Diaz G, Garnacho-Montero J, et al. Improvement in process of care and outcome after a multicenter severe sepsis educational program in Spain. JAMA. 2008;299:2294–303.

El Solh AA, Akinnusi ME, Alsawalha LN, Pineda LA. Outcome of septic shock in older adults after implementation of the sepsis “bundle”. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:272–8.

Nguyen HB, Corbett SW, Steele R, Banta J, Clark RT, Hayes SR, et al. Implementation of a bundle of quality indicators for the early management of severe sepsis and septic shock is associated with decreased mortality. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:1105–12.

Eskelinen M, Ikonen J, Lipponen P. Diagnostic approaches in acute cholecystitis; a prospective study of 1333 patients with acute abdominal pain. Theor Surg. 1993;8:15–20.

Staniland JR, Ditchburn J, De Dombal FT. Clinical presentation of acute abdomen: study of 600 patients. Br Med J. 1972;3:393–8.

Trowbridge RL, Rutkowski NK, Shojania KG. Does this patient have acute cholecystitis? JAMA. 2003;289:80–6.

Hirota M, Takada T, Kawarada Y, Nimura Y, Miura F, Hirata K, et al. Diagnostic criteria and severity assessment of acute cholecystitis: Tokyo Guidelines. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2007;14:78–82. (clinical practice guidelines: CPGs).

Ralls PW, Halls J, Lapin SA, Quinn MF, Morris UL, Boswell W. Prospective evaluation of the sonographic Murphy sign in suspected acute cholecystitis. J Clin Ultrasound. 1982;10:113–5.

Soyer P, Brouland JP, Boudiaf M, Kardache M, Pelage JP, Panis Y, et al. Color velocity imaging and power Doppler sonography of the gallbladder wall: a new look at sonographic diagnosis of acute cholecystitis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;171:183–8.

Indar AA, Beckingham IJ. Acute cholecystitis. BMJ. 2002;325:639–43.

Law C, Tandan V. Gallstone disease: surgical treatment. In: Based Evidence, editor. Gastroenterology and hepatology. London: BMJ Books; 1999. p. 260–70.

Cameron IC, Chadwick C, Phillips J, Johnson AG. Acute cholecystitis—room for improvement? Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2002;84:10–3.

Noble VE, Liteplo AS, Nelson BP, Thomas SH. The impact of analgesia on the diagnostic accuracy of the sonographic Murphy’s sign. Eur J Emerg Med. 2010;17:80–3.

Akriviadis EA, Hatzigavriel M, Kapnias D, Kirimlidis J, Markantas A, Garyfallos A. Treatment of biliary colic with diclofenac: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:225–31.

Kumar A, Deed JS, Bhasin B, Thomas S. Comparison of the effect of diclofenac with hyoscine-N-butylbromide in the symptomatic treatment of acute biliary colic. Aust NZ J Surg. 2004;74:573–6.

Goldman G, Kahn PJ, Alon R, Wiznitzer T. Biliary colic treatment and acute cholecystitis prevention by prostaglandin inhibitor. Dig Dis Sci. 1989;34:809–11.

Sugiyama M, Tokuhara M, Atomi Y. Is percutaneous cholecystostomy the optimal treatment for acute cholecystitis in the very elderly? World J Surg. 1998;22:459–63.

Chopra S, Dodd GD 3rd, Mumbower AL, Chintapalli KN, Schwesinger WH, Sirinek KR, et al. Treatment of acute cholecystitis in non-critically ill patients at high surgical risk: comparison of clinical outcomes after gallbladder aspiration and after percutaneous cholecystostomy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176:1025–31.

Yokoe M, Takada T, Strasberg SM, Solomkin JS, Mayumi T, Gomi H, et al. New diagnostic criteria and severity assessment of acute cholecystitis in revised Tokyo guidelines. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2012;19:578–85.

Inui K, Nakazawa S, Naito Y, Kimoto E, Yamao K. Nonsurgical treatment of cholecystolithiasis with percutaneous transhepatic cholecystoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1988;83:1124–7.

Boland GW, Lee MJ, Mueller PR, Dawson SL, Gaa J, Lu DS, et al. Gallstones in critically ill patients with acute calculous cholecystitis treated by percutaneous cholecystostomy: nonsurgical therapeutic options. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1994;162:1101–3.

Majeed AW, Reed MW, Ross B, Peacock J, Johnson AG. Gallstone removal with a modified cholecystoscope: an alternative to cholecystectomy in the high-risk patient. J Am Coll Surg. 1997;184:273–80.

Shirai Y, Tsukada K, Kawaguchi H, Ohtani T, Muto T, Hatakeyama K. Percutaneous transhepatic cholecystostomy for acute acalculous cholecystitis. Br J Surg. 1993;80:1440–2.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our deep gratitude to the Japanese Society for Abdominal Emergency Medicine, the Japan Biliary Association, Japan Society for Surgical Infection, and the Japanese Society of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Surgery, which provided us with great support and guidance in the preparation of the Guidelines.

Conflict of interest

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

About this article

Cite this article

Miura, F., Takada, T., Strasberg, S.M. et al. TG13 flowchart for the management of acute cholangitis and cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 20, 47–54 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00534-012-0563-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00534-012-0563-1