Abstract

Water temperature has received considerable attention as steering factor for the genesis of different types of marine carbonate sediments. However, parameters other than temperature also strongly influence ecosystems and, consequently, the carbonate grain associations in the resulting carbonate rock. Among those factors are biological evolution, water energy, substrate, water chemistry, light penetration, trophic conditions, CO2 concentrations, and Mg/Ca ratios in the seawater. Increased nutrient levels in warm-water settings, for example, lead to heterotrophic-dominated associations that are characteristic of temperate to cool-water carbonates. Failure to recognize the influence of such environmental factors that shift the grain associations towards heterotrophic communities in low latitudes can lead to misinterpretation of climatic conditions in the past. Modern analogues of low-latitude heterozoan carbonates help to recognize and understand past occurrences of heterozoan warm-water carbonates. Careful analysis of such sediments therefore is required in order to achieve robust reconstructions of past climate.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction: carbonate sediments as environmental archives

The increasing public focus on climatic and global changes makes reliable environmental reconstructions of the past more crucial than ever. The record of the past is an important basis for understanding the processes, interactions and dynamics of changing environmental conditions. The short-term changes we observe today are but snap shots. Hence, for extrapolating current trends, for assessing causes, dynamics, and reaction strategies, a deep-time perspective is extremely valuable. Sedimentary rocks are the most important archives of environmental conditions during Earth history. Among sedimentary rocks, carbonates are particularly valuable, because they are mostly of biogenic origin and thus record environmental conditions with a wealth of different facets.

Until the end of the 1960s, it was generally accepted that the formation of volumetrically significant carbonate deposits is restricted to the tropical-subtropical climate belt. In fact, the approach to study modern systems as analogues for ancient deposits was developed in warm-water settings (Ginsburg 1956, 1957; Purdy 1961, 1963). It was only in the late 1960s when it was recognized that significant carbonate production also takes place outside the tropics in settings where terrigenous influx is restricted (Chave 1967). Generally, the region of tropical carbonate sedimentation is separated from extra-tropical regions of carbonate formation by the 20°C winter isotherm (e.g., Betzler et al. 1997); however, the distribution of modern coral reefs is constrained by winter minimum temperatures above 18°C (Newell 1971; Belasky 1996). In the 1980s, numerous studies have dealt with modern extra-tropical carbonates, in particular in the southern hemisphere (Nelson et al. 1988; James and Bone 1989; James et al. 1992; James 1997). During the 1990s, numerous studies focused on carbonate settings of polar regions (Henrich et al. 1992, 1997; Andruleit et al. 1996; Freiwald 1998; Rao et al. 1998). Modern deep-water carbonates came into focus with improved marine technology, and since the late 1990s, intensive research of benthic deep-water carbonates such as coral mounds takes place (see reviews of Roberts et al. 2006, 2009).

The approach to study modern analogues has greatly improved the interpretation of ancient carbonate rocks (e.g., Grammer et al. 2004). Studies of modern carbonate depositional systems establish relationships between external parameters that, in contrast to the geological past, can be directly measured (cf. Westphal et al. 2010). This includes oceanographic parameters such as seasonality, trophic conditions, temperature, and salinity (Lees and Buller 1972; Carannante et al. 1988). In contrast, studies of ancient carbonate systems have traditionally focused on the interpretation of temperature and relative sea-level position (e.g., Kendall and Schlager 1981; Handford and Loucks 1993). More recent studies of ancient carbonates emphasize the influence of trophic conditions and ocean chemistry among other factors (Pomar 2001a; Hallock 2001; Pomar et al. 2004).

While the actualistic concept of the three large carbonate realms (warm, cold, deep) is by now well established (see Schlager 2003), the large and diverse group of carbonates that do not fit into this scheme is currently strongly under-represented in the literature. Wright and Burgess (2005) developed the concept of a carbonate production continuum in order to include the latter. Carbonate sediments that do not fit into the traditionally recognized realms appear atypical from the actualistic point of view; for example, heterotrophic-dominated carbonate sediments in warm-water low-latitude settings are rare in the modern world. However, associations that are unusual today might have been typical during intervals of Earth history when different environmental boundary conditions or different biotic strategies prevailed.

Only isolated modern examples of such “atypical” carbonates have been studied in detail so far. Thus, comparison to and interpretation of ancient occurrences remain difficult. The recognition of such carbonates, however, is of utmost importance for paleoclimate research. For example, misinterpretation of fossil carbonates formed in the tropics under elevated nutrient conditions as cool-water carbonates would lead to wrong paleoclimatic reconstructions that might ultimately be used as input for climate modelling. For achieving reliable climatic and environmental reconstructions, the differentiation of the various environmental influences is required. Classical carbonate sedimentological tools for the definition of carbonate facies and carbonate grain associations can be inadequate if the spectrum of external influences is not included in the interpretation (e.g., hydrography, productivity), as well as the biological reactions to environmental change in time and space (physiological adaptation, shifts in the species spectra; e.g., Henrich et al. 1995). An understanding of the carbonate depositional systems is also important for reservoir rock characterization. Architecture, ecological accommodation, facies distribution and diagenetic potential sensibly react to changes of the biological community (Pomar 2001a, b; Knörich and Mutti 2006).

In spite of the increasing recognition of influences beyond temperature, the literature is still dominated by temperature or paleolatitude interpretations of carbonate grain associations. One reason is that a concept of heterozoan and transitional photozoan-heterozoan (cf. Halfar et al. 2006) carbonates in warm-water low-latitude settings has not yet been formally established. The aim of this paper is therefore to provide an overview of these heterozoan warm-water carbonates and the control mechanisms leading to their specific composition.

Carbonate grain associations as climate and latitudinal indicators

Classical tropical carbonates are largely produced by autotrophic and mixotrophic biota such as zooxanthellate corals and calcareous green algae. They are restricted to oligotrophic waters, because the strategy of photosymbiosis and internal recycling is most successful under nutrient-limited conditions (Hallock 1981; Wood 1993). Also, photoautotrophic organisms are adapted to low nutrient levels and are suppressed in high-nutrient settings (Hallock and Schlager 1986; Hallock 1987; Schlager 2003).

In the modern world, carbonate sediments that are mainly produced by heterotrophic organisms are dominant in temperate to polar regions (see James 1997). However, they also occur in the tropics where the oceanographic situation suppresses typical tropical chlorozoan carbonates (Logan et al. 1969; Simone and Carannante 1988; Hallock et al. 1988; Carannante et al. 1988). Controls that influence the formation of heterozoan versus chlorozoan carbonates in the tropics include temperature, salinity, water depth, trophic conditions, oxygen and CO2 concentrations and Mg/Ca ratio in the seawater, alkalinity, morphology and bathymetry of the sea-floor, the type of substrate, transparency of the water column, internal waves and water stratification (Hallock and Schlager 1986; Hallock et al. 1988; Carannante et al. 1988; Bourrouilh-Le Jan and Hottinger 1988; Stanley and Hardie 1998; Pomar and Ward 1995, 1999; Pomar 2001a; Mutti and Hallock 2003; Pomar et al. 2004; Wright and Burgess 2005). Some of these conditions are strongly influenced by coupled atmospheric and oceanographic circulation patterns. For example, trade wind cells and the stable subtropical gyres of the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans cause upwelling preferably along the western sides of continents; the formation of the near-equatorial oceanic upwelling belt follows the Intertropical Convergence Zone. Other factors, such as eustacy, tectonics, and sea-floor morphology determine the accommodation space, the extension and the morphology of the carbonate factory (e.g., Handford and Loucks 1993; Reijmer et al. 1992). Trophic conditions, temperature, and water energy determine the biotic associations (e.g., Hallock and Schlager 1986). Type and location of the carbonate production determine the base level of sediment accumulation and thus the platform morphology and dynamics (Pomar 2001b).

Lees and Buller (1972) and Lees (1975) already emphasized that modern foramol sediments are not restricted to extratropical areas but occur also in the tropics and subtropics (Fig. 1). Similarly, James (1997) pointed out that while cool-water carbonates are always heterozoan carbonates, the heterozoan association is not indicative of cool-water carbonates. An exception is the distribution of phototrophic calcareous red algae. These Corallinaceae differ from typical chlorozoan elements in that they tolerate higher nutrient levels than other phototrophic or symbiotic organisms, and their genera are adapted to temperatures that span from tropical to polar conditions (e.g., Freiwald 1998).

Latitudinal distribution of carbonate facies as a function of water depth modified from Carannante et al. (1988). The axis indicating increasing water depth (and thus decreasing water temperature and light) in the original figure here also serves for other parameters such as increasing nutrient concentrations

The influence of trophic conditions has been increasingly recognized in carbonate sedimentology over the past decades (Hallock and Schlager 1986; Carannante et al. 1988; Birkeland 1987; Hallock 1988, 2001; Pomar et al. 2004). The most important biolimiting nutrients for carbonate depositional systems are phosphorous, iron, silica and nitrogen (Brasier 1995a). Nutrients can be introduced into the sedimentary system by several processes including oceanic upwelling, fluvial transport, wind transport and volcanic eruptions (Vogt 1989; Mutti and Hallock 2003; J. Michel, G. Mateu-Vicens, H. Westphal, 2010, Eutrophic tropical carbonate grain associations—the Golfe d’Arguin, Mauritania, submitted). Changes in trophic conditions result in shifts in the diversity, composition, trophic structure and stability of the biological community (Valentine 1971; Stanton and Dodd 1976, Brasier 1995a, b).

The systematic paleoecological interpretation of ancient carbonate rocks usually applies the characterization of grain associations, that is, the characteristic combinations of remains of carbonate secreting organisms (Lees 1975). The coralgal association is composed of skeletal remains of corals and green algae; the chloralgal association is dominated by green algae. Together they are typical for oligotrophic tropical conditions (Lees and Buller 1972) and correspond to the chlorozoan group (James 1997). Foramol (Lees and Buller 1972), rhodalgal and molechfor (Carannante et al. 1988), bryomol (Nelson et al. 1988), and bryohyalosponge (Beauchamp 1994) associations correspond to the heterozoan group of James (1997) and are well known from the extra-tropics. Henrich et al. (1995) have shown in studies of arctic and subarctic carbonates that a distinction between tropical and arctic carbonates simply on the basis of component associations is impossible. They conclude that the interpretation of grain associations is insufficient without considering the trophic conditions and without including knowledge of the biogeographical affinities of genera or species involved in carbonate sedimentation. This can be exemplified by the cosmopolitan group of coralline algae. While today Sporolithaceae are characteristic of low latitude, mainly deep-water settings, melobesioid corallinaceans occur also in high latitude, shallow-water settings, whereas lithophylloid and mastophoroid corallinaceans are characteristic of mid to low latitudinal shallow waters (Aguirre et al. 2000). Hence, the incorporation of taxonomic knowledge to carbonate-grain association promises a very valuable source of information but this often remains unrecognized in sedimentological studies.

Biological evolution, however, limits the applicability of modern grain associations as analogues for interpreting past latitudinal position or paleotemperatures. For example, Carannante et al. (1995) have shown that in certain stratigraphic intervals, foramol associations have even dominated the tropics, as for example in Upper Cretaceous rudist bearing limestones, which have formed in the tropics. Therefore, caution is required when interpreting ancient carbonate grain associations in terms of latitudes or temperatures without considering taxonomic evidence and other environmental parameters.

Modern heterozoan warm-water carbonates

In contrast to oligotrophic tropical carbonate depositional systems, modern heterozoan tropical carbonates are comparably rare. Generally, temperature and nutrient levels are anticorrelated in modern oceans (e.g., Halfar et al. 2006). In settings with enhanced fluvial input, increased nutrient levels are generally accompanied by a decrease in salinities and an increase in sediment load. However, there are few examples where cool upwelling waters warm up on broad shallow tropical shelves while staying saline and meso- and eutrophic. Such examples allow for singling out the effects of trophic conditions.

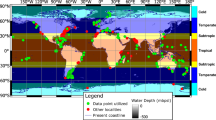

In the following, modern heterozoan warm-water carbonate depositional systems are described. Study of modern systems has the great advantage that environmental parameters can be directly measured, allowing for linking sediment parameters to environmental (oceanographic, ecologic) conditions. Therefore, modern analogue studies are a crucial step for understanding heterotrophic warm-water carbonates in the rock record. The following modern occurrences of warm-water heterozoan carbonates are categorized according to the dominant steering mechanisms (Figs. 2, 3).

Location of modern heterozoan warm-water carbonates discussed in text. White letters indicate high-nutrient setting; black letters indicate settings where factors other than trophic conditions suppress typical tropical photozoan communities. (A) Mauritania; (B) Yucatan; (C) Nicaragua Rise; (D) West Florida Shelf; (E) Gulf of California; (F) Fernando de Noronha; (G) Persian Gulf; (H) Shark Bay, W-Australia; (I) Cocos Island; (J) Galapagos Islands; (K) NE Brazilian shelf; (L) Eastern Mediterranean. Map shows primary production based on chlorophyll concentrations (annual average, September 1997—August 1998) (http://marine.rutgers.edu/opp/swf/Production/results/all2_swf.html)

Nutrient-temperature scheme modified after Halfar et al. (2006). Examples discussed in text are indicated (where chlorophyll-a values were available) with letters as in Fig. 3. The geographical gradients of (E) and (G) are indicated by arrows. Note that several examples discussed in text plot in the photozoan field; these are the examples where steering factors other than nutrients and temperature suppress the development of a photozoan community. The plot was originally designed for normal-marine salinities; examples with elevated salinities therefore here are marked by grey letters. Temperature and chlorophyll values are from Halfar et al. (2006) or from description of examples in text

Trophic conditions

Nutrients can stimulate growth of phytoplankton that reduces water transparency, limiting depth ranges of zooxanthellate corals and calcareous algae, and thereby reducing phototrophic carbonate production (Hallock and Schlager 1986). Hence, if nutrient and food resources are plentiful, small fast growing groups including filamentous algae, barnacles, and bryozoans among others are superior competitors for space to corals (Birkeland 1987). A modest increase in nutrient flux causes a shift from coral to mixed coral-algal domination, and a substantial increase in nutrient flux produces a shift from coral to filter-feeding domination with non-symbiotic and heterotrophic biota (Hallock 2001).

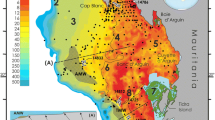

NW-African shelf of Northern Mauritania

The generally narrow continental shelf of most parts of NW-Africa (<65 km) widens off N-Mauritania to some 150 km at the Golfe d’Arguin. This extensive gulf hosts the shallow Banc d’Arguin with water depths of less than 10 and in many areas less than 1 m. The waters off N-Mauritania are among the most productive marine areas (3 mg * m−3 Chl-a (chlorophyll-a), e. g., Marañón and Holligan 1999) in the world and are important fishing grounds. The reason for the high productivity lies in the elevated nutrient levels caused by oceanic upwelling and by additional fertilization by high desert dust input. Cold oceanic upwelling along the NW African coastline stretches from 12°N to 33°N (Mittelstaedt 1991; Van Camp et al. 1991) and gives rise to the formation of cool-water carbonates that dominate most of this region (Summerhayes et al. 1976). An exception is the Golfe d’Arguin, where the upwelling waters warm up to subtropical-tropical temperatures that on the Banc d’Arguin can exceed 25°C in summer and do not drop below 18°C in winter; where the upwelling waters enter the bank, minimum temperatures are at 16°C (Peters 1976, Koopmann et al. 1979). At the same time trophic levels remain high, thus producing eutrophic warm-water conditions.

In the shallow northern part of the Golfe d’Arguin, the Baie du Lévrier, the elevated nutrient levels result in a sediment grain association composed of barnacles, worm tubes, red algae, bryozoans, and alcyonarians; in settings below the wave base, ostracods, foraminifers, echinoderms, sponge spicules, diatoms and fish remains prevail (Koopmann et al. 1979). The originally cold temperature of the upwelling waters is documented by cool-water planktonic foraminifers such as Neogloboquadrina pachyderma that are transported onto the bank and into the bay (Koopmann et al. 1979; J. Michel, G. Mateu-Vicens, H. Westphal, 2010, Eutrophic tropical carbonate grain associations—the Golfe d’Arguin, Mauritania, submitted).

South of the Baie du Lévrier the sediment is dominated by bivalves with abundant fish remains and serpulid tubes (Fig. 4a; J. Michel, G. Mateu-Vicens, H. Westphal, 2010, Eutrophic tropical carbonate grain associations—the Golfe d’Arguin, Mauritania, submitted). Organisms typical of oligotrophic tropical settings (e.g., zooxanthellate corals and green algae) are absent. The species spectrum of the molluscs is very narrow as typical for high-nutrient settings. The bivalve Crassatina sp. and gastropods like Prunum annulatum, Persicula cingulata, and Marginella sebastiani demonstrate that tropical water temperatures prevail (Fig. 4b). The minor role of red algae has been explained by a lack of hard substrate (Milliman 1977) and by the low light transparency (J. Michel, G. Mateu-Vicens, H. Westphal, 2010, Eutrophic tropical carbonate grain associations—the Golfe d’Arguin, Mauritania, submitted; J. Michel, H. Westphal, R. von Cosel, 2010, The mollusk fauna of soft sediments from the tropical, upwelling-influenced shelf of Mauritania (NW Africa), submitted).

Examples of modern heterozoan warm-water carbonate grain associations: a, b Foramol sediment from the Golfe d’Arguin, Mauritania. a Coarse-fraction shows abundant fish remains indicating high biological productivity, and a dominance of the bivalve Donax burnupi. b Tropical gastropod Persicula cingulata demonstrates the warm-water conditions. c, d) Modern heterozoan sediment from the Gulf of California. c Red-algal-dominated sediment from mesotrophic section of gulf, d Bryomol sediment from eutrophic northern Gulf of California

Yucatan Shelf off Mexico

On the Yucatan Shelf (20–23°N) in the Gulf of Mexico, photozoan carbonates (reef buildups with Porites and Acropora) with well-developed coral reefs form in direct vicinity of heterozoan tropical carbonates (Logan 1969; Logan et al. 1969). Topographical upwelling in the east of the Yucatan Shelf is thought to be responsible for the suppression of photozoan carbonates on the eastern shelf. The Yucatan Shelf receives no terrigenous input, because no fresh water reaches the coastline of the highly karstified hinterland (Merino 1997). Sea surface temperatures average between 24 and 30°C, but cool, nutrient-rich upwelling waters (17–18°C) from the Yucatan channel periodically (in spring and early summer) reach the eastern side of the shelf (Merino 1997), leading to temporarily increased primary production on the order of 1 mg * m−3 Chl-a, which corresponds to meso-/eutrophic conditions (Martínez-López and Zavala-Hidalgo 2009). While the waters warm up on the shelf, the trophic level remains elevated. The resulting carbonate sediment is characterized by foramol composition. Down to water depths of 50–80 m the sediment consists of bivalves, gastropods, Halimeda plates, and red algal fragments, plus peneroplids and miliolids (Logan et al. 1969). No information is available on the sediment composition in the easternmost part of the Yucatan Shelf where the upwelling water masses hit the shelf. Aragonite mud, an important component of classical tropical carbonates, is restricted to the western Yucatan Shelf where coral reefs prevail (Hoskin 1963). Because the Yucatan Shelf is not protected by a continuous reef barrier, the sedimentary system is strongly influenced by high water energies caused by currents and storms.

Nicaragua Rise

On the Nicaragua Rise, carbonate accumulation on the shallow platforms of the Nicaragua Rise has not kept pace with Holocene sea-level rise, despite a tropical location remote from terrigenous sedimentation (Hallock et al. 1988). Topographical upwelling causes elevated nutrient levels on the western Nicaragua Rise (Roberts and Murray 1983; Hine et al. 1987; Hallock et al. 1988; Triffleman et al. 1992). The decreasing trophic resources from west to east are accompanied by a gradient in the association of carbonate producers (Hallock et al. 1988). On the western platforms of the Nicaragua Rise, trophic resources exceed levels favouring coral-reef development, and sponge-algal communities predominate (cf. Hallock and Schlager 1986). Carbonate sediment on the western platforms is produced by calcareous green algae such as Halimeda (Hine et al. 1987), which makes the western Nicaragua Rise a chloralgal tropical carbonate system characterized by an absence of corals. This is in contrast to the well-developed coral reefs along the Jamaican coast on the eastern Nicaragua Rise.

West Florida Shelf

On the West Florida Shelf (26–28°N), high fluvial input of fine-grained terrigenous material raises nutrient levels (Gould and Steward 1956; Doyle 1986), while tropical water temperatures persist (20–30°C; Gorsline 1963). This results in a suppressed coral carbonate production, accompanied by high percentages of green algal-dominated carbonates. Hence, an impoverished photozoan carbonate community persists under elevated trophic resources, but tropical sea surface temperatures.

Gulf of California, Mexico

Located in a low-latitude setting (23° to 30°N), the Gulf of California is characterized by warm-temperate conditions (minimum monthly water temperatures in the south of 19°C and in the north 10°C; Alvarez-Borrego 1983) and encompasses nutrient regimes from oligo-mesotrophic in the south to eutrophic in the north (Alvarez-Borrego and Lara-Lara 1991; Halfar et al. 2006). Along with increasing nutrients, depth of light penetration decreases. Accordingly, carbonate production ranges from coral- dominated shallow-water areas in the south to extensive rhodolith-dominated, inner shelf carbonate production in the central gulf, and to molluscan-bryozoan inner- to outer-shelf environments in the northern gulf (Fig. 4b, c; Halfar et al. 2006). With respect to modern rhodolith-dominated carbonates, the Gulf of California is one of the best-studied regions in the world (Steller and Foster 1995; Hetzinger et al. 2006). While zooxanthellate corals are present throughout the gulf, they form a reef-like structure only in the southernmost oligotrophic setting (Riegl et al. 2007). Other photozoan carbonate producers such as green algae are not found in the sediment, even though sparse living plants have been observed in the southern gulf (Halfar et al. 2006). In contrast to classical coralgal sediments, the carbonates and coral structures from the Gulf of California are poorly cemented (Halfar et al. 2001). While the Gulf of California carbonates were calibrated against in situ measured nutrient and temperature time series in order to highlight the influence of increasing trophic conditions along a gradient of carbonate systems, the accompanying trend of decreasing temperatures complicated the interpretation.

Water energy

Water energy also has a suppressing effect on zooxanthellate reefs. In continuously or sporadically high-energy settings, other photozoan organisms (red algae, stromatolites) replace the typical tropical coralgal association.

Fernando de Noronha (Brazil)

The island (3°25′S) off the Brazilian coast is exposed to extremely high water energy related to tidal forces (Jindrich 1983). Because of unrestricted wave fetch, ocean swell creates heavy surf with a spring tide range of 255 cm (Jindrich 1983). The carbonate framework here is composed of calcareous algae (Neogoniolithon, Sporolithon) and vermetid gastropods (Dendropoma) complemented by other encrusters such as Homotrema, bryozoans, serpulids and barnacles (Branner 1904; Kempf and Laborel 1968; Laborel 1969; Jindrich 1983). Halimeda and hermatypic corals locally form dense structures but no true reefs (Jindrich 1983). In addition to the high tidal energy, the geographical isolation could play a role in inhibiting coral reef development by hindering larval dispersal. Early cementation by aragonite and HMC is pervasive and is interpreted to be a result of the high tidal energy (Jindrich 1983).

Salinity

Lees and Buller (1972) already pointed out the role of salinity for the development of the different carbonate grain associations. The optimum range for chlorozoan associations is roughly at 31–40‰; outside this range the community shifts towards an association of euryhaline opportunists.

Persian Gulf, Red Sea, Tunisian Shelf

The Persian Gulf is characterized by high seasonal temperature variations, high salinity, low clarity and nutrient-poor water. Salinity is a major controlling factor determining the composition of carbonate-producing biota. Persian Gulf corals have partly adjusted to this high variability and can tolerate higher salinity and temperature changes. In areas with >50‰ salinity, corals, calcareous algae and echinoderms and most of the foraminifers are absent (Poiriez et al. 2010; Purser 1973).

In contrast, in the Red Sea, salinities are also elevated (40–46‰; Piller and Rasser 1996); however, green algae are present, albeit in rather low abundance and coral reefs are developed (Piller and Mansour 1990; Gabrié and Montaggioni 1982). Green algae are also abundant components in the sediments on the hypersaline Tunisian Shelf (Burollet 1981) and the Tunisian Ghar El Melh lagoon that shows strongly elevated salinities (44‰ in summer with extreme values of up to 54‰; Shili et al. 2002). The relationship between elevated salinities and the occurrence of calcareous green algae thus is not clear.

Shark Bay, W-Australia

Shark Bay shows a strong salinity gradient from normal-salinity tropical waters to extremely hypersaline waters in Hamelin Pool (56–65‰; Logan 1961). The high salinities in Hamelin Pool lead to a strong restriction of multicellular benthic organisms (mainly the zooxanthellate bivalve Fragum erugatum; Berry and Playford 1997), thus giving way to the formation of algal mat-mediated stromatolites. These stromatolites with their living cyanobacterial surface were the first modern stromatolites described (Logan 1961). It is now well known that stromatolites also prosper in normal-marine salinities where competing benthos is restricted, e.g., by mechanical stress as for the Bahamian stromatolites that grow in high-energy, ooid-loaded waters (Reid et al. 1995).

Oscillating oceanographic conditions

Tropical East Pacific

The tropical East Pacific is a region of poor coral-reef development due to a shallow thermocline, internal wave oscillations, slightly reduced salinity in areas close to coastlines, and high seasonal turbidity (Dana 1975). The impoverished nature of eastern Pacific coral communities is most likely a result of temporal and spatial isolation from source areas of high diversity, and of frequent disturbances that are peculiar to this region (Glynn 1996). Specifically, coral-reef development is suppressed by sporadically occurring cold-water intrusions associated with a shallowing of the thermocline during El Nino events (Glynn 1994). In the Gulf of Chiriquí at the Costa Rican Pacific Coast, temperature changes related to thermocline variability reach some 7°C; changes that should be detrimental to hermatypic coral growth (Dana 1975). In fact, the 1982/83 El Nino event resulted in 95–99% mortality of the coral communities in Galapagos (0°32′S) and Cocos Islands (5°32′N), with recovery being slow (Glynn 1997). Instead, carbonate producers that are more tolerant to temperature changes, such as coralline red algae and barnacles, have established flourishing communities, with barnacles (Balanus tintinnabulum and Tetraclita sp.) forming reef-like accumulations around Cocos Island (Glynn and Wellington 1983; Senn and Glasstetter 1989). Individual balanids reach sizes of 80 mm in height and form thick accumulations as a result of gregarious settlement. Coralline red algae stabilize the barnacle aggregations. Coralline algae are important ecosystem components in many areas of the Galapagos (Glynn and Wellington 1983) where they locally form rhodolith beds (Foster 2001).

A recently discussed factor adding to the impoverished nature of Eastern Pacific coral communities is the low pH and low aragonite saturation state of the seawater in this area (Manzello et al. 2008). This low pH is the consequence of upwelling mixing CO2-enriched deep waters into the surface layers along the shallow thermocline (e.g., Manzello et al. 2008). It results in poor cementation of coral reef structures and may favour the high bioerosion rates previously reported for Eastern Tropical Pacific reefs (Eakin 1996). However, elevated nutrients in upwelled waters may also limit cementation and/or stimulate bioerosion (Manzello et al. 2008). Conditions leading to aragonite undersaturation are even more pronounced during recurring El Nino events that force enhanced upwelling of CO2-rich deep water. Hence, tropical carbonate systems similar to the ones of the East Pacific might become more common globally with an expected increase in ocean acidification (De’ath et al. 2009).

Geographical situation

NE-Brazilian shelf

On the tropical Brazilian shelf between 0 and 15°S, carbonate sediments are dominated by Halimeda and ramiform red algae with subordinate encrusting red algae, rhodolites, bryozoans and large benthic foraminifers (Amphistegina, Archaias) (Milliman and Summerhayes 1975; Vicalvi and Milliman 1977; Carannante et al. 1988). Zooxanthellate corals are rare with a low diversity and a high degree of endemism (Spalding et al. 2001, p. 173).

Between 15 and 23°S, encrusting red algae and rhodoliths dominate. Here, zooxanthellate corals are entirely absent. While parts of the tropical Brazilian shelf are influenced by fluvial runoff, in the semiarid NE of Brazil, only little sediment load from the Amazon and San Francisco rivers reach the shelf, and the waters are clear, show temperatures of 26.5–28.5°C and normal salinity (Testa and Bosence 1999). These conditions would be expected to favour the development of typical tropical carbonates that in fact are largely absent here. The reason is thought to be an oceanographic blocking of the southward transport of coral planulae from the Caribbean to the Brazilian shelf by the low-salinity and high-sediment load plume of the Amazon river (Spalding et al. 2001, p. 173). Testa and Bosence (1999) suggest that additionally the extremely high water energy and the continuous movement of sediment counteracts benthic settling. Wilson (1986, 1988) has pointed out that low-diversity benthic communities are characteristic for strongly moving sediments and high water energy conditions.

Eastern Mediterranean

The oligotrophic (Patara et al. 2009) Eastern Mediterranean with its subtropical water temperatures (14–28°C) and salinites (>37‰; Morel 1971) largely lacks zooxanthellate coral reefs (the only zooxanthellate hermatypic coral is Cladocora caespitosa). Here, the absence of a tropical corridor is held responsible for the scantiness of tropical elements.

The formerly rich warm-water fauna of the Mediterranean, including zooxanthellate coral reefs, vanished during the Messinian salinity crisis. When the connection to the open ocean opened again at the straits of Gibraltar, new ecosystems established (Bouillon et al. 2004). Today, the Western Mediterranean is richer in marine species than the Eastern basin. One reason put forward is that the Eastern Mediterranean with its great tropical affinity is isolated from tropical species entering from Gibraltar by the temperate barrier of the Western Mediterranean (Bouillon et al. 2004). This assumption is corroborated by the observation that since the opening of the Suez Canal, tropical species invading from the Red Sea now thrive and expand in the Eastern Mediterranean (Bouillon et al. 2004).

Ancient heterozoan warm-water carbonates

An increasing number of ancient occurrences of heterozoan warm-water carbonates have been recognized lately; mostly from the Neogene of the Western Mediterranean (Brandano and Corda 2002; Pomar et al. 2002, 2004; see also Halfar and Mutti 2005), but also from the Mesozoic (Hornung et al. 2007). These occurrences are reminiscent of cool-water carbonates but have formed under warm-water conditions with increased trophic levels as evidenced by the predominance of nutrient-tolerant groups of calcareous organisms, supported in some cases by high amounts of suspension feeders and high rates of bioerosion. These examples demonstrate the potential importance of heterozoan warm-water carbonates throughout the Phanerozoic. However, the documented number of examples in the rock record is still limited. One reason might be that they have not yet been recognized as such. Most of the described occurrences are of Neogene age, pointing to the fact that the older the rock, the more difficult it is to interpret carbonate rocks on the basis of modern analogues. For interpreting heterozoan carbonate deposits, it is crucial to separate the relative influence of different parameters such as temperature, trophic conditions and ocean chemistry, etc. (e.g., Pomar et al. 2005; Halfar et al. 2006). In the following, examples are presented that have been interpreted as tropical carbonates in spite of their heterozoan character, and the steering mechanisms for the biotic associations are discussed.

Changing trophic conditions

Upper Miocene, Balearic Islands

On the Balearic Islands, a foramol-rhodalgal carbonate ramp (Tortonian to lower Messinian; Fig. 5) is stratigraphically succeeded by a zooxanthellate coral reef (upper Messinian; Pomar 2001a). The ramp system is of tropical origin as suggested by larger foraminifers and the red algal association (Brandano et al. 2005; Mateu-Vicens et al. 2008). The transition from the ramp system to the rimmed reef platform thus is not driven by water temperature; rather, it reflects the transition from a humid to a more arid climate that is implied by paleoclimatic reconstructions (Pomar et al. 2004). The terrigenous input from the hinterland during the formation of the ramp had suppressed the development of a classical tropical reef system. When the terrigenous input was diminished by arid conditions, the zooxanthellate coral reef system could establish.

Example from ancient heterozoan tropical carbonate ramp (lower Tortonian, Menorca). a Upper slope clinobeds composed of rhodolithic rudstone/floatstones with red algal grainstone matrix. Deposition is thought to have taken place close to the site of production in the deepest photic zone. Bed thickness is about 50 cm. b Red algae (Sporolithon) in upper slope rhodolithic rudstone clinobeds. c Larger benthic foraminifers (Heterostegina) indicative of subtropical to tropical conditions. d Cast of the trace of cyanobacterium Fasciculus rogus tentatively indicating elevated trophic conditions

Mid to upper Miocene, Lazio-Abruzzi platform, Apennines

This Serravallian-Tortonian carbonate succession is a foramol carbonate ramp system. Taxonomic studies have shown that the red algae are clearly tropical (Brandano 2001; Brandano and Corda 2002). In addition, rare hermatypic corals have been found. The high density of suspension feeders and the intense bioerosion point to elevated trophic conditions. The increasing nutrient levels have been interpreted to reflect the development of a foredeep and the approach of the orogenic front of the Apennines.

Mid-Miocene, tropical Pacific Islands

In the Mid-Miocene, rhodolith-dominated facies with a thickness exceeding 100 m succeeds the Early Miocene coral-reef deposits over wide areas of the equatorial Pacific Islands (Bourrouilh-Le Jan and Hottinger 1988). Major carbonate components of these tropical rhodolite facies are Halimeda and larger foraminifers (Bourrouilh-Le Jan 1979). The facies change from hermatypic coral to rhodolite deposits is explained by a thinning of the uppermost oligotrophic layer related to equatorial climate cooling and sea-level fall, introducing elevated nutrient conditions to near-surface water masses (Bourrouilh-Le Jan and Hottinger 1988).

Mid-Miocene, Pannonian Basin, Hungary

These rhodolith-dominated sediments have originally been interpreted as cool-water carbonates (Randazzo et al. 1999). However, rare Porites patch reefs demonstrate that the sediment formed under warm-water conditions (Halfar et al. 2000). Elevated trophic conditions are thought to have suppressed the flourishing of classical coral reefs. The origin of the nutrients has yet to be determined.

Early to late Miocene, SE-Asia

SE Asia has the most extensive and complete record of equatorial carbonates spanning the last 20 My (Burdigalian-early Tortonian; Wilson 2008). Declining SE Asian coral-reef facies were replaced in the late Early Miocene by large benthic foraminiferal biofacies with abundant coralline red algae (Wilson 2002). This facies is especially abundant in areas of terrestrial runoff or upwelling, with an indication that nutrients (high oligotrophy to mesotrophy rather than eutrophy) may have influenced Cenozoic development of this biofacies (Wilson and Vecsei 2005). Nutrient upwelling in SE Asia is a result of oceanic ventilation with enhanced thermohaline circulation and narrowing of oceanic gateways due to tectonic movement in the Indo-Pacific. In addition, seasonal runoff increased through initiation and/or intensification of the monsoons (Fulthorpe and Schlanger 1989; Wilson 2008).

Upper Cretaceous, NW Sardinia, Southern Appenines and Apulia

In large parts of Italy, tropical foramol sediments of Upper Cretaceous age crop out (Carannante et al. 1995, 1997; Simone et al. 2003). In this time interval, a strong increase in molluscs (most markedly in rudists) and red algae took place. The rudists replaced corals as dominant reef-building organisms. Other common carbonate-secreting organisms include bryozoans and benthic foraminifers whereas green algae disappear. At the same time, the amount non-skeletal components and aragonite cements decreases. These changes are interpreted to imply that the sediments have formed in deeper, darker, and more eutrophic conditions as the underlying typical tropical coral-bearing carbonates. However, as Pomar et al. (2005) pointed out, the Cretaceous corals flourished in deeper water than their modern equivalents, questioning the water-depth interpretation. Carannante et al. (1995) demonstrate that the extensive development of foramol associations in the tropical-subtropical seas of the Upper Cretaceous point to increased trophic conditions. High nutrient levels favour low-diversity associations of heterotrophic suspension feeders such as rudists (Scott 1995). In addition, in contrast to corals, the heterotrophic rudists were able to occupy mobile substrates (Pomar et al. 2005).

Upper Cretaceous, Northern Spain

The Upper Santonian to Lower Campanian Lacazina limestones consist of a foramol association (whereby the molluscs are dominated by bivalves with only subordinate rudists) that has been deposited under warm-water elevated trophic conditions (Gischler et al. 1994). Elevated nutrient levels caused by terrigenous input, possibly in concert with upwelling, have suppressed reef growth and the formation of a chlorozoan association. This is supported by the dominance of miliolid foraminifers that are known to replace other benthic foraminifers under high nutrient conditions (Hallock 1985).

Lower Cretaceous, Northern Spain

The lowermost Aptian in the central part of the Northern Cantabrian Basin is represented by a carbonate ramp depositional system (Wilmsen 2005). The facies is of mixed chloralgal-foramol character with a strongly dominant foramol association. Hermatypic corals are absent, and the biofacies is dominated by heterotrophic organisms such as oysters, brachiopods, echinoids, solitary corals. A strong terrigenous input under wet-subtropical climate is held responsible for high-nutrient warm-water conditions (Wilmsen 2005). The voluminous fluvial input is manifested in abundant siliciclastic grains and plant debris. Thus, the heterozoan carbonate facies was controlled by elevated nutrient levels rather than temperature (Wilmsen 2005).

Upper Triassic, NW Tethys

In the Carnian of the NW Tethys, a demise of coral reef–rimmed platforms was followed by the development of carbonate ramps, which were then again succeeded by rimmed reef platforms. This non-reefal interval has been interpreted to be related to a pronounced increase in precipitation, the so-called Carnian Pluvial Event (Simms and Ruffell 1989; Keim et al. 2001; Rigo et al. 2007; Hornung et al. 2007). Climate warming in the mega-monsoonal Triassic climate has intensified the hydrologic cycle and increased humidity (e.g., Parrish 1999; Wortmann and Weissert 2000) resulting in enhanced freshwater runoff that led to higher nutrient levels and a lowered salinity in the ocean. This nutrification of and increased sediment input into sea surface waters could have had negative consequences for Upper Triassic shallow-marine coral reef builders, which lived in assumed symbiosis with zooxanthellate algae (Stanley and Swart 1995; Kiessling 2002). The increased abundance of epibenthic suspension feeders suggests increased nutrient supply (Keim et al. 2001). Coevally, elevated nutrient supply advanced growth of fixosessile microbes and stimulated planktonic blooms. This leads to reduced water transparency, destabilisation of coral symbiosis, enhanced by increased bio-erosion (Keim et al. 2001). The dominance of megalodonts places this example in the foramol grain association.

Other examples of heterozoan tropical carbonates from Earth history that have been related to elevated trophic conditions include the middle to upper Permian shelves of Pangaea (Beauchamp and Desrochers 1997; Weidlich 2002) and some intervals of the Silurian of Gotland (Jeppsson 1990; Kershaw 1993; Bickert et al. 1997).

Changing ocean chemistry

The expansion of shallow-water aragonite factories in the Late Oligocene-Early Miocene (Budd 2000) has been interpreted to reflect declining atmospheric CO2 concentrations to Neogene levels (Pearson and Palmer 2000). Scleractinian coral reef frameworks show a pronounced peak in abundance in the Late Miocene when CO2 reached preindustrial concentrations (Perrin 2002; Pomar and Hallock 2007). Ocean chemistry appears to be a major determinant of the modes of calcification and shell mineralogies preferably precipitated by photozoans (Hallock 1996, 2005; Stanley and Hardie 1998). Observations in the modern world imply that increasing atmospheric pCO2 acts on marine carbonate secreting biota by reducing the carbonate saturation (in particular the aragonite saturation) in seawater, thus leading to reduced calcification of the skeletons (Opdyke and Wilkinson 1993; Kleypas et al. 1999; Kleypas and Langdon 2001; Hallock 2005; De’ath et al. 2009).

In addition, the concentration of Ca2+ and the Mg/Ca ratios significantly influence carbonate-secreting organisms. The combination of high Ca2+ concentrations with low Mg/Ca ratios seem to have a stronger influence on the dominance of calcite precipitation over aragonite than high atmospheric CO2 concentrations such as in the Cretaceous (Stanley and Hardie 1998; Ries 2006).

Evolutionary change

During Earth history, a wide range of organisms has filled the ecological niche of shallow-water reefs (e.g., Pomar and Hallock 2008; Kiessling 2005). Among those organisms were phototrophic as well as heterotrophic and symbiotic framework builders. In addition, several groups of carbonate-secreting organisms have migrated between different ecological niches and thus indicate different ecological conditions in different time intervals. Due to biological evolution, the deeper in time, the more difficult it is to interpret the paleoecology of carbonate deposits.

But even in the younger Earth history, interpretations of facies are far from straightforward. Zooxanthellate corals expanded into shallow-water habitats in the Late Miocene (Pomar and Hallock 2008). Global cooling in combination with changing seawater chemistry that supported hypercalcification of aragonitic corals (cf. Ries et al. 2006) is suggested to have led to the migration of the corals in the shallow euphotic zone (Pomar and Hallock 2007). However, the coevolution of corals and Symbiodinium zooxanthellae appears to have played an important role for the migration into shallow waters. Previously, the limited capacity of zooxanthellate corals to thrive in high-light conditions is thought to have prevented them from forming a wave-resistant reef (Pomar and Hallock 2007, 2008). This promoted the dominance of heterozoan assemblages in oligotrophic tropical waters, e.g., in the Upper Oligocene sediments of Malta that form a carbonate ramp dominated by coralline algae (Brandano et al. 2009). Similarly, in SE Asia, Paleogene carbonates were dominated by coralline algae and benthic foraminifers with only scarce corals despite tropical latitudes (Wilson and Rosen 1998; Wilson 2008).

Other steering mechanisms

Differentiating the various steering mechanisms is difficult in the geological past, and it becomes more difficult the less is known about the oceanography of the time slice, and the deeper in time the carbonate system has formed. Nevertheless, there are reports of other controlling factors than the aforementioned trophic conditions, CO2 and Ca2+ concentrations, Mg/Ca ratio, and evolutionary change, leading to the development of heterozoan warm-water carbonate facies. These include water energy (e.g., those Cretaceous rudists that were adapted to high-water energies: Simone et al. 2003; the high-energy rhodolite platforms of the Mio-Pliocene Pacific: Bourrouilh-Le Jan 1979), and salinity (among many other examples the stromatolites and serpulid or sabellarid reefs of the Messinian in the Western Mediterranean, Esteban 1979).

Heterozoan warm-water carbonates—more abundant in Earth history?

In the modern world, heterozoan warm-water carbonates are restricted to a variety of settings that appear disturbed compared to the tropical oligotrophic coralgal carbonates we regard as typical for modern tropical carbonate depositional settings. However, during large intervals of Earth history, heterozoan warm-water carbonates might have been the rule rather than the exception. During greenhouse periods, the hydrological cycle was strongly enforced and thus has led to increased evaporation, precipitation, erosion, fresh-water and sediment influx in warm ocean waters. It seems likely that during such periods, high-nutrient, heterotrophic dominated carbonates have been more abundant than in our present-day icehouse world with its oceanic deserts in the tropics. It might be speculated that as a result of current climate warming, such high-nutrient settings will expand. Thus, the examples presented here might serve as models for future developments—with possible consequences, e.g., on coastal protection where coral reefs disappear. Similar, for better predicting the effect of future increasing pCO2 and ocean acidification, modern heterozoan carbonate-depositional systems offer important information.

As Pomar and Kendall (2007) have pointed out, study of the various types of carbonate depositional systems in the geological record will demonstrate the wide variety of environmental conditions and ecosystem reactions and finally lead to deemphasizing the Holocene uniformitarian approach. The continuum approach of Wright and Burgess (2005) offers a first basis for filling the gaps between the classical carbonate depositional realms.

Recognizing ancient heterotrophic warm-water tropical carbonates

Recognizing heterozoan warm-water carbonates is a prerequisite for reaching reliable interpretations of heterozoan carbonate deposits. As pointed out earlier and illustrated with the examples given, carbonate grain associations are inadequate for this task. Other tools are required to support a well-founded interpretation. These approaches are listed in Table 1.

Conclusions

A wide range of parameters can suppress coralgal carbonates in warm-water settings; this includes elevated trophic conditions but also high water energies, geographical isolation, instability of the oceanographic conditions, and many others. The current models of carbonate depositional realms are based on an actualistic approach—from this actualistic point of view, the widespread heterozoan associations in the past are atypical. However from the perspective of other intervals of Earth history, heterozoan warm-water carbonates were the rule rather than the exception.

As already pointed out by the authors elsewhere, more calibration studies are needed to define the mulitparameter space of carbonate grain associations (e.g., nutrients-temperature, Gulf of California: Halfar et al. 2004; Golfe d’Arguin: (J. Michel, G. Mateu-Vicens, H. Westphal, 2010, Eutrophic tropical carbonate grain associations—the Golfe d’Arguin, Mauritania, submitted; J. Michel, H. Westphal, R. von Cosel, 2010, The mollusk fauna of soft sediments from the tropical, upwelling-influenced shelf of Mauritania (NW Africa), submitted). As detailed earlier, useful tools for distinguishing between extratropical carbonates and warm-water heterozoan carbonates include taxonomic study, oceanographic context, and geochemical proxies. Study of such examples will extend the understanding of such ecosystems, allow for calibrating further proxies, and it will help to better predict future changes in the oceans.

References

Aguirre J, Riding R, Braga JC (2000) Diversity of coralline red algae: origination and extinction patterns from the Early Cretaceous to the Pleistocene. Paleobiology 26:651–667

Alvarez-Borrego S (1983) Gulf of California. In: Ketchum BH (ed) Ecosystems of the World 26: Estuaries and enclosed seas. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 427–449

Alvarez-Borrego S, Lara-Lara JR (1991) The physical environment and primary productivity of the Gulf of California. In: Dauphin JP, Simoneit BRT (eds) The Gulf and Peninsular Province of the Californias. American Association of Petroleum Geologists, Tulsa, pp 555–567

Andruleit H, Freiwald A, Schäfer P (1996) Bioclastic carbonate sediments on the southwestern Svalbard shelf. Mar Geol 134:163–182

Beauchamp B (1994) Permian climatic cooling in the Canadian Arctic. In: Klein GD (ed) Pangea: paleoclimate, tectonics, and sedimentation during accretion, zenith, and breakup of a supercontinent, vol 288. Geological Society of America Special Paper, Boulder, pp 229–246

Beauchamp B, Desrochers A (1997) Permian warm- to very cold-water carbonates in Northwest Pangea. In: James NP, Clarke JAD (eds) Cool-water carbonates, vol 56. SEPM Special Publication, pp 327–347

Belasky P (1996) Biogeography of Indo-Pacific larger foraminifera and scleractinian corals: a probabilistic approach to estimating taxonomic diversity, faunal similarity, and sampling bias. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 122:119–141

Berry PF, Playford PE (1997) Biology of modern Fragum erugatum (Mollusca, Bivalvia, Cardiidae) in relation to deposition of the Hamelin Coquina, Shark Bay, Western Australia. Mar Freshw Res 48:415–420

Betzler C, Brachert TC, Nebelsick J (1997) The warm temperate carbonate province–A review of facies, zonations, and delimitations. Courier Forschungs-Institut Senckenberg 201:83–99

Bickert T, Pätzold J, Samtleben C, Munnecke A (1997) Paleoenvironmental changes in the Silurian indicated by stable isotopes in brachiopod shells from Gotland, Sweden. Geochim Cosmochim Acta 61:2717–2730

Birkeland C (1987) Nutrient availability as a major determinant of differences among coastal hard-substratum communities in different regions of the tropics. In: Birkeland C (ed) Differences between Atlantic and Pacific tropical marine coastal systems: community structure, ecological processes, and productivity. UNESCO, Paris, pp 45–90

Bouillon J, Medel MD, Pagès F, Gili JM, Boero F, Gravili C (2004) Fauna of the Mediterranean Hydrozoa. Scientia Marina 68(Suppl. 2):5–438

Bourrouilh-Le Jan FG, Hottinger LC (1988) Occurrence of rhodolites in the tropical Pacific—a consequence of Mid-Miocene paleo-oceanographic change. Sediment Geol 60:355–367

Bourrouilh-Le Jan FG (1979) Les plates-formes carbonatees de haute energie a Rhodolithes et la crise climatique du passage Mio-Pliocene dans le domaine pacifique: Bulletin Centre Recherche Exploration-Production. Elf-Aquitane 3:489–495

Brandano M (2001) Risposta fisica delle aree di piattaforma carbonatica agli eventi piu` significativi del Miocene nell’Appennino Centrale. PhD Thesis, University of Rome ‘La Sapienza’, Rome, 180 pp

Brandano M, Corda L (2002) Nutrients, sea level and tectonics: constrains for the facies architecture of a Miocene carbonate ramp in central Italy. Terra Nova 14:257–262

Brandano M, Vannucci G, Pomar L, Obrador A (2005) Rhodolith assemblages from the lower Tortonian carbonate ramp of Menorca (Spain): environmental and paleoclimatic implications. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 226:307–323

Brandano M, Frezza V, Tomassetti L, Cuffaro M (2009) Heterozoan carbonates in oligotrophic tropical waters: the Attard member of the Lower Coralline Limestone formation (Upper Oligocene, Malta). Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 274:54–63

Branner JC (1904) The stone reefs of Brazil. In: Bulletin Museum of Comparative Zoology, vol 44. Harvard University, pp 1–285

Brasier MD (1995a) Fossil indicators of nutrient levels. 1: eutrophication and climate change. In: Bosence DWJ, Allison PA (eds) Marine Paleoenvironmental Analysis from Fossils, vol 83. Geological Society London Special Publication, pp 113–132

Brasier MD (1995b) Fossil indicators of nutrient levels. 2: evolution and extinction in relation to oligotrophy. In: Bosence DWJ, Allison PA (eds) Marine Paleoenvironmental Analysis from Fossils, vol 83. Geological Society London Special Publication, pp 133–150

Budd AF (2000) Diversity and extinction in the Cenozoic Caribbean reefs. Coral Reefs 19:25–35

Burollet PF (1981) The Pelagian Sea east of Tunisia: bioclastic deposition under temperate climate. Mar Geol 44:157–170

Carannante G, Esteban M, Milliman JD, Simone L (1988) Carbonate lithofacies as paleolatitude indicators: problems and limitations. Sediment Geol 60:333–346

Carannante G, Cherchi A, Simone L (1995) Chlorozoan versus foramol lithofacies in Upper Cretaceous rudist limestones. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 119:137–154

Carannante G, Graziano R, Ruberti D, Simone L (1997) Upper Cretaceous temperate-type open shelves from northern (Sardinia) and southern (Apennines-Apulia) Mesozoic Tethyan margins. In: James NP, Clarke J (eds) Cool-water carbonates, vol 56. SEPM Special Publication, pp 309–325

Chave KE (1967) Recent carbonate sediments—an unconventional view. J Geol Educ 15:200–204

Dana TF (1975) Development of contemporary Eastern Pacific coral reefs. Mar Biol 33:355–374

De’ath G, Lough JM, Fabricius KE (2009) Declining coral calcification on the Great Barrier Reef. Science 323:116–119

Doyle LJ (1986) Carbonate comparison of West Florida continental margin with margins of Eastern United States. AAPG Bull 70:583

Eakin CM (1996) Where have all the carbonates gone? A model comparison of calcium carbonate budgets before and after the 1982–1983 El Niño at Uva Island in the eastern Pacific. Coral Reefs 15:109–119

Esteban M (1979) Significance of the Upper Miocene reefs of the Western Mediterranean. Paleogeogr Paleoclimatol Paleoecol 29:169–188

Foster MS (2001) Rhodoliths: between rocks and soft places. J Phycol 37:659–667

Freiwald A (1998) Modern nearshore cold-temperate calcareous sediments in the Troms District, northern Norway. J Sediment Res 68:763–776

Fulthorpe CS, Schlanger SO (1989) Paleo-oceanographic and tectonic settings of early Miocene reefs and associated carbonates of offshore Southeast Asia. Am Assoc Pet Geol Bull 73:729–756

Gabrié L, Montaggioni L (1982) Sedimentary facies from the modern coral reefs, Jordan Gulf of Aqaba, Red Sea. Coral Reefs 1:115–124

Ginsburg RN (1956) Environmental relationships of grain size and constituent particles in some South Florida carbonate sediments. AAPG Bull 40:2384–2427

Ginsburg RN (1957) Early diagenesis and lithification of shallow water carbonate sediments in South Florida. In: Le Blanc RJ, Breeding JG (eds) Regional aspects of carbonate deposition, vol 5. SEPM Special Publication, pp 80–100

Gischler E, Graeffe K-U, Wiedmann J (1994) The Upper Cretaceous Lacazina Limestone in the Basco-Cantabrian and Iberian Basins of northern Spain: cold-water grain associations in warm-water environments. Facies 30:209–246

Glynn PW (1994) State of coral reefs in the Galapagos islands: natural vs anthropogenic impacts. Mar Pollut Bull 29:131–140

Glynn PW (1996) Coral reefs of the Eastern Pacific. Coral Reefs 15:69

Glynn PW (1997) Assessment of the present health of coral reefs in the Eastern Pacific. In: Grigg RW, Birkeland C (eds) Status of Coral Reefs in the Pacific, UNIHI Sea Grant CP-98-01, pp 33–40

Glynn PW, Wellington GM (1983) Corals and coral reefs of the Galapagos islands: Berkeley and Los Angeles. University of California Press, California, 330 p

Gorsline DS (1963) Environments of carbonate deposition, Florida Bay and the Florida Straits. In: Bass RO (ed) Shelf carbonates of the Paradox basin. Four Corners Geological Society Symposium, 4th Field Conference, pp 130–143

Gould HR, Steward RH (1956) Continental terrace sediments in the northeastern Gulf of Mexico. In: Hough JL, Menard HW (eds) Finding ancient shore lines, vol 3. SEPM Special Publication, pp 2–19

Grammer GM, Harris PM, Eberli GP (eds) (2004) Integration of Outcrop Modern Analogs, vol 80. AAPG Memoir, 394 p

Halfar J, Mutti M (2005) Global dominance of coralline red-algal facies: A response to Miocene oceanographic events. Geology 33:481–484

Halfar J, Godinez-Orta L, Ingle JC (2000) Microfacies analysis of recent carbonate environments in the southern Gulf of California, Mexico—A model for warm-temperate to subtropical carbonate formation. Palaios 15:323–342

Halfar J, Godinez-Orta L, Goodfriend GA, Mucciarone DA, Ingle JC, Holden P (2001) Holocene—Late Pleistocene non-tropical carbonate sediments and tectonic history of the western rift basin margin of the southern Gulf of California. Sediment Geol 144:149–178

Halfar J, Godinez-Orta L, Mutti M, Valdez-Holguín J, Borges JM (2004) Nutrient and temperature controls on modern carbonate production: an example from the Gulf of California, Mexico. Geology 32:213–216

Halfar J, Godinez-Orta L, Mutti M, Valdez-Holguin JE, Borges JM (2006) Carbonates calibrated against oceanographic parameters along a latitudinal transect in the Gulf of California, Mexico. Sedimentology 53:297–320

Hallock P (1981) Production of carbonate sediments by selected large benthic foraminifera on two Pacific coral reefs. J Sediment Petrol 51:467–474

Hallock P (1985) Why are larger foraminifera large? Paleobiology 11:195–208

Hallock P (1987) Fluctuations in the trophic resource continuum: a factor in global diversity cycles? Paleoceanography 2:457–471

Hallock P (1988) The role of nutrient availability in bioerosion: consequences to carbonate buildups. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 63:275–291

Hallock P (1996) Reefs and reef limestones in Earth history. In: Birkeland C (ed) Life and death of coral reefs. Chapman and Hall, New York, pp 13–42

Hallock P (2001) Coral reefs, carbonate sediments, nutrients, and global change. In: Stanley GD (ed) The history and sedimentology of ancient reef systems. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, New York, pp 387–427

Hallock P (2005) Global change and modern coral reefs: new opportunities to understand shallow-water carbonate depositional processes. Sediment Geol 175:19–33

Hallock P, Schlager W (1986) Nutrient excess and the demise of coral reefs and carbonate platforms. Palaios 1:389–398

Hallock P, Hine AC, Vargo GA, Elrod JA, Jaap WC (1988) Platforms of the Nicaraguan rise: examples of the sensitivity of carbonate sedimentation to excess trophic resources. Geology 16:1104–1107

Handford CR, Loucks RG (1993) Carbonate depositional sequences and systems tracts—responses of carbonate platforms to relative sea-level changes. In: Loucks RG, Sarg JF (eds) Carbonate sequence stratigraphy, vol 57. AAPG Memoir, pp 3–41

Henrich R, Hartmann M, Reitner J, Schäfer P, Freiwald A, Steinmetz S, Dietrich P, Thiede J (1992) Facies belts and communities of the Arctic Vesterisbanken Seamount (Central Greenland Sea). Facies 27:71–104

Henrich R, Freiwald A, Betzler C, Bader B, Schäfer P, Samtleben C, Brachert TTC, Wehrmann A, Zankl H, Kühlmann DHH (1995) Controls on modern carbonate sedimentation on warm-temperate to Arctic coasts, shelves and seamounts in the Northern Hemisphere: implications for fossil counterparts. Facies 32:71–108

Henrich R, Freiwald A, Bickert T, Schäfer P (1997) Evolution of an Arctic open-shelf carbonate platform, Spitsbergen Bank (Barents Sea). In: James NP, Clarke JAD (eds) Cool-water carbonates, vol 56. SEPM Spec. Publ, pp 163–184

Hetzinger S, Halfar J, Riegl B, Godinez-Orta L (2006) Sedimentology and acoustic mapping of modern rhodolith facies on a non-tropical carbonate shelf (Gulf of California, Mexico). J Sediment Res 76:670–682

Hine A, Hallock P, Harris MW, Mullins HT, Belknap DF, Jaap WC (1987) Halimeda bioherms along an open seaway: Miskito Channel, Nicaraguan Rise, SW Caribbean Sea. Coral Reefs 6:173–178

Hornung T, Brandner R, Krystyn L, Joachimski MM, Keim L (2007) Multistratigraphic constraints on the NW Tethyan “Carnian crisis”. In: Lucas SG, Spielmann JA (eds) The Global Triassic, vol 41. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, pp 59–67

Hoskin CM (1963) Recent carbonate sedimentation on Alacran reef, Yucatan, Mexico. Natl Acad Sci—Natl Research Council Pub 1089:1–160

James NP (1997) The cool-water carbonate depositional realm. In: James NP, Clarke J (eds) Cool-water Carbonates, vol 56. SEPM Special Publication, pp 1–20

James NP, Bone Y (1989) Petrogenesis of Cenozoic, temperate water calcarenites, south Australia: a model for meteoric/shallow burial diagenesis of shallow water calcite sediments. J Sediment Petrol 59:191–203

James NP, Bone Y, von der Borch CC, Gostin VA (1992) Modern carbonate and terrigenous clastic sediments on a cool water, high energy, mid-latitude shelf: Lacepede, southern Australia. Sedimentology 29:877–903

Jeppsson L (1990) An oceanic model for lithological and faunal changes tested in the Silurian record. J Geol Soc London 147:663–674

Jindrich V (1983) Structure and diagenesis of recent algal-foraminifer reefs, Fernando de Noronha, Brazil. J Sediment Petrol 53:449–458

Keim L, Brandner R, Krystyn L, Mette W (2001) Termination of carbonate slope progradation: an example from the Carnian of the Dolomites, Northern Italy. Sediment Geol 143:303–323

Kempf M, Laborel J (1968) Formations de vermets et d’algues calcaires sur les côtes du Brésil. Recueil des Travaux de la Station. Marine d’Endoume 43:9–23

Kendall CGSC, Schlager W (1981) Carbonates and relative changes in sea level. Mar Geol 44:181–212

Kershaw S (1993) Sedimentation control on growth of stromatoporoid reefs in the Silurian of Gotland, Sweden. J Geol Soc Lond 150:197–205

Kiessling W (2002) Secular variations in the Phanerozoic reef ecosystem. In: Kiessling W, Flügel E, Golonka J (eds) Phanerozoic reef patterns, vol 72. SEPM Special Pubication, pp 625–690

Kiessling W (2005) Long-term relationships between ecological stability and biodiversity in Phanerozoic reefs. Nature 433:410–413

Kleypas J, Langdon C (2001) Overview of CO2-induced changes in seawater chemistry. Proceedings of the 9th International Coral Reef Symposium, Bali, vol 2, pp 1085–1089

Kleypas JA, Buddemeier RW, Archer D, Gattuso J-P, Langdon C, Opdyke BN (1999) Geochemical consequences of increased atmospheric carbon dioxide on coral reefs. Science 284:118–120

Knörich AC, Mutti M (2006) Missing aragonitic biota and the diagenetic evolution of heterozoan carbonates: a case study from the Oligo-Miocene of the central Mediterranean. J Sediment Res 76:871–888

Koopmann B, Lees A, Piessens P, Sarnthein M (1979) Skeletal carbonate sands and wind-derived silty-marls off the Saharan coast: Baie du Lévrier, Arguin Platform, Mauritania. Meteor Forsch Ergeb C 30:15–57

Kroopnick PM (1985) The distribution of 13C of ΣCO2 in the world oceans. Deep Sea Res Part I Oceanogr Res Pap 32:57–84

Laborel J (1969) Les peuplements de madréporaires des côtes tropicates du Brésil. Annales de l’Universite d’ Abidjan Série E 3:1–261

Lea DW, Boyle EA (1990) Foraminiferal reconstruction of barium distributions in water masses of the glacial oceans. Paleoceanography 5:719–742

Lea DW, Boyle EA (1993) Determination of carbonate-bound barium in foraminifera and corals by isotope dilution plasma-mass spectrometry. Chem Geol 103:73–84

Lees A (1975) Possible influence of salinity and temperature on modern shelf carbonate sedimentation. Mar Geol 19:159–198

Lees A, Buller AT (1972) Modern temperate water and warm water shelf carbonate sediments contrasted. Mar Geol 13:M67–M73

Logan BW (1961) Cryptozoan and associate stromatolites from the Recent, Shark Bay, Western Australia. J Geol 69:517–533

Logan BW (1969) Coral reefs and banks, Yucatan shelf, Mexico. In: Carbonate sediments and reefs, vol 11. Yucatan Shelf, Mexico. AAPG Memoir, pp 129–198

Logan BW, Harding JL, Ahr WM, Williams JD, Snead RG (1969) Late Quaternary sediments of Yucatan Shelf, Mexico. In: Carbonate sediments and reefs, vol 11. Yucatan Shelf, Mexico. AAPG Memoir, pp 5–128

Manzello DP, Kleypas JA, Budd DA, Eakin CM, Glynn PW, Langdon C (2008) Poorly cemented coral reefs of the eastern tropical Pacific: possible insights into reef development in a high-CO2 world. In: Proceedings PNAS, vol 105, pp 10450–10455

Marañón E, Holligan PM (1999) Photosynthetic parameters of phytoplankton from 50°N to 50°S in the Atlantic Ocean. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 176:191–203

Martínez-López B, Zavala-Hidalgo J (2009) Seasonal and interannual variability of cross-shelf transports of chlorophyll in the Gulf of Mexico. J Mar Syst 77:1–20

Mateu-Vicens G, Brandano M, Hallock P (2008) Depositional model and paleoecological reconstruction of the lower Tortonian distally steepened ramp of Menorca (Balearic Islands, Spain). Palaios 23:465–481

Merino M (1997) Upwelling on the Yucatan Shelf: hydrographic evidence. J Mar Syst 13:101–121

Milliman JD (1977) Role of calcareous algae in Atlantic continental margin sedimentation. In: Flügel E (ed) Fossil Algae. Springer, Berlin, pp 232–247

Milliman JD, Summerhayes CP (1975) Upper continental margin sedimentation off Brazil. E. Schweizerbart’sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Stuttgart, p 175

Mittelstaedt E (1991) The ocean boundary along the northwest African coast: circulation and oceanographic properties at the sea surface. Prog Oceanogr 26:307–355

Morel A (1971) Caractères hydrologiques des eaux échangées entre la bassin oriental et le basin occidental de la Méditerranée. Cahiers Océanographiques 27:4

Mutti M, Hallock P (2003) Carbonate systems along nutrient and temperature gradients: some sedimentological and geochemical constraints. Int J Earth Sci 92:465–475

Nelson CS, Keane SL, Head PS (1988) Non-tropical carbonate deposits on the modern New Zealand shelf. Sediment Geol 60:71–94

Newell ND (1971) An outline history of tropical organic reefs. Am Mus Novit 2465:1–37

Opdyke BN, Wilkinson BH (1993) Carbonate mineral saturation state and cratonic limestone accumulation. Am J Sci 293:217–234

Parrish JT (1999) Pangaea und das Klima der Trias. In: Hauschke N, Wilde V (eds) Trias–eine ganz andere Welt. Pfeil Verlag, München, pp 37–42

Parrish JT, Droser ML, Bottjer DJ (2001) A Triassic upwelling zone: the Shublik Formation, Arctic Alaska, USA. J Sediment Res 71:272–285

Patara L, Pinardi N, Corselli C, Malinverno E, Tonani M, Santoleri R, Masina S (2009) Particle fluxes in the deep Eastern Mediterranean basins: the role of ocean vertical velocities. Biogeosciences 6:333–348

Pearson PN, Palmer MR (2000) Atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations over the past 60 million years. Nature 406:695–699

Perrin C (2002) Tertiary: the emergence of modern reef ecosystems. In: Kiessling W, Flügel E, Golonka J (eds) Phanerozoic Reef Patterns, vol 72. Soc. Econ. Paleont. Mineral. Spec. Publ, pp 587–621

Peters H (1976) The spreading of the water masses of the Banc d’Arguin in the upwelling area off the northern Mauritanian coast. “Meteor” Forschungsergebnisse A 18:78–100

Philip JM, Gari J (2005) Late Cretaceous heterozoan carbonates: palaeoenvironmental setting, relationships with rudist carbonates (Provence, south-east France). Sediment Geol 175:315–337

Piller WE, Mansour AM (1990) The northern Bay of Safaga (Red Sea, Egypt): an actuopaleontological approach, II. Sediment analyses and sedimentary facies. Beitr Paläont Österr 16:1–102

Piller WE, Rasser M (1996) Rhodolith formation induced by reef erosion in the Red Sea, Egypt. Coral Reefs 15:191–198

Poiriez A, Riegl B, Bergman KL, Westphal H, Janson X, Eberli GP (2010) The Persian Gulf—Facies belts, physical and chemical parameters of the ocean? In: Westphal H, Riegl B, Eberli GP (eds) Assessing dimensions and controlling parameters in carbonate depositional systems. Springer (in press)

Pomar L (2001a) Ecological control of sedimentary accommodation: evolution from carbonate ramp to rimmed shelf, Upper Miocene, Balearic Islands. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 175:249–272

Pomar L (2001b) Types of carbonate platforms: a genetic approach. Basin Res 13:313–334

Pomar L, Kendall CGStC (2007) Architecture of carbonate platforms: a response to hydrodynamics and evolving ecology. In: Lukasik J, Simo A (eds) Controls on carbonate platform and reef development, vol 89. SEPM Special Publication, pp 187–216

Pomar L, Hallock P (2007) Changes in coral-reef structure through the Miocene in the Mediterranean province: adaptive versus environmental influence. Geology 35:899–902

Pomar L, Hallock P (2008) Carbonate factories: a conundrum in sedimentary geology. Earth Sci Rev 87:134–169

Pomar L, Ward WC (1995) Sea-level changes, carbonate production and platform architecture: the Llucmajor platform, Mallorca, Spain. In: Haq BU (ed) Sequence stratigraphy and depositional response to eustatic, tectonic and climatic forcing. Kluwer Academic Press, Dordrecht, pp 87–112

Pomar L, Ward WC (1999) Reservoir-scale heterogeneity in depositional packages and diagenetic patterns on a reef-rimmed platform, upper Miocene, Mallorca, Spain. Bull AAPG 83:1759–1773

Pomar L, Obrador A, Westphal H (2002) Sub-wavebase cross-bedded grainstones on a distally steepened carbonate ramp, upper Miocene, Menorca, Spain. Sedimentology 49:139–169

Pomar L, Brandano M, Westphal H (2004) Miocene tropical foramol-rhodalgal-bryomol associations of the western Mediterranean—a critical review. Sedimentology 51:627–651

Pomar L, Gili E, Obrador A, Ward WC (2005) Facies architecture and high resolution sequence stratigraphy of an upper Cretaceous platform margin succession, Southern Central Pyrenees, Spain. Sediment Geol 175:339–365

Purdy EG (1961) Bahamian oolite shoals. In: Peterson JA, Osmond JC (eds) Geochemistry of sandstone bodies, AAPG Special Volume, p 232

Purdy EG (1963) Recent calcium carbonate facies of the Great Bahama-Bank, 1. Petrography and reaction group, 2. Sedimentary facies. J Geol 71(334–355):472–497

Purser BH (1973) Sedimentation around bathymetric highs in the southern Persian Gulf. In: Purser BH (ed) The Persian Gulf. Springer, Berlin, pp 157–177

Randazzo AF, Müller P, Lelkes G, Juhász E, Hámor T (1999) Cool-water limestones of the Pannonian basinal system, Middle Miocene, Hungary. J Sediment Res 69:283–293

Rao CP, Goodwin ID, Gibson JAE (1998) Shelf, coastal and subglacial polar carbonates, East Antarctica. Carbonates Evaporites 13:174–188

Reid RP, Macintyre IG, Browne KM, Steneck RS, Miller T (1995) Modern marine stromatolites in the Exuma Cays, Bahamas: uncommonly common. Facies 33:1–17

Reijmer JJG, Schlager W, Bosscher H, Beets CJ, McNeill DF (1992) Pliocene/Pleistocene platform facies transition recorded in calciturbidites (Exuma Sound, Bahamas). Sediment Geol 78:171–179

Riegl B, Halfar J, Purkis SJ, Godinez-Orta L (2007) Sedimentary facies of the eastern Pacific’s northernmost reef-like setting (Cabo Pulmo, Mexico). Mar Geol 236:61–77

Ries JB (2006) Aragonitic algae in calcite seas: effect of seawater Mg/Ca ratio on algal sediment production. J Sediment Res 76:515–523

Rigo M, Preto N, Roghi G, Tateo F, Mietto P (2007) A rise in the carbonate compensation depth of western Tethys in the Carnian (Late Triassic): deep-water evidence for the Carnian Pluvial Event. Paleogeogr Paleoclimatol Palaeoecol 246:188–205

Roberts HH, Murray SP (1983) Controls on reef development and the terrigenous-carbonate interface on a shallow shelf, Nicaragua (Central America). Coral Reefs 2:71–80

Roberts JM, Wheeler AJ, Freiwald A (2006) Reefs of the deep: the biology and geology of cold-water coral ecosystems. Science 312:543–547

Roberts JM, Wheeler A, Freiwald A, Cairns S (2009) Cold-Water Corals: the biology and geology of deep-sea coral habitats. Cambridge University Press, 352 pp

Schlager W (2003) Benthic carbonate factories of the Phanerozoic. Int J Earth Sci 92:445–464

Scott RW (1995) Global environmental controls on Cretaceous reefal ecosystems. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 119:187–199

Senn DG, Glasstetter M (1989) On the occurrence of Barnacle-Reefs around Cocos-Island, Costa Rica. Senckenb Marit 20:241–249

Shili A, Trabelsi EB, Ben Maïz N (2002) Benthic macrophyte communities in the Ghar El Melh lagoon (North Tunisia). J Coastal Conserv 8:135–140

Simms MJ, Ruffell AH (1989) Synchroneity of climate change and extinctions in the Late Triassic. Geology 17:265–268

Simone L, Carannante G (1988) The fate of foramol (“temperate-type”) carbonate platforms. Sediment Geol 60:347–354

Simone L, Carannante G, Ruberti D, Sirna M, Sirna G, Laviano A (2003) Development of rudist lithosomes in the Coniacian–Lower Campanian carbonate shelves of central southern Italy: high-energy vs low-energy settings. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 200:5–29

Spalding M, Ravilious C, Green EP (2001) World atlas of coral reefs. University of California Press, 424 p

Stanley MS, Hardie LA (1998) Secular oscillations in the carbonate mineralogy of reefbuilding and sediment-producing organisms driven by tectonically forced shifts in seawater chemistry. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol 144:3–19

Stanley GD Jr, Swart PK (1995) Evolution of the coral-zooxanthellae symbiosis during the Triassic: a geochemical approach. Paleobiology 21:179–199

Stanton RJ (2006) Nutrient models for the development and location of ancient reefs. Geo Alp 3:191–206

Stanton RJ, Dodd JR (1976) The application of trophic structure of fossil communities in paleoenvironmental reconstruction. Lethaia 9:327–342

Steller DL, Foster MS (1995) Environmental factors influencing distribution and morphology of rhodoliths in Bahia Concepción, B.C.S, Mexico. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 194:201–212

Struck U, Heyn T, Altenbach A, Alheit J, Emeis KC (2004) Distribution and nitrogen isotope ratios of fish scales in surface sediments from the upwelling area off Namibia. Zitteliana A44:125–132

Summerhayes CP, Milliman JD, Briggs SR, Bee AG, Hogan C (1976) Northwest African shelf sediments: influence of climate and sedimentary processes. J Geol 84:277–300