Abstract

Purpose

Patients with head and neck cancer (HNC) experience significant symptom burden from combination chemotherapy and radiation (chemoradiation) that affects acute and long-term health-related quality of life (HRQOL). However, psychosocial impacts of HNC symptom burden are not well understood. This study examined psychosocial consequences of treatment-related symptom burden from the perspectives of survivors of HNC and HNC healthcare providers.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional, mixed-method study conducted at an NCI-designated comprehensive cancer center. Participants (N = 33) were survivors of HNC who completed a full course of chemoradiation (n = 20) and HNC healthcare providers (n = 13). Participants completed electronic surveys and semi-structured interviews.

Results

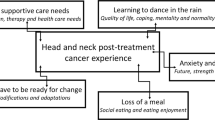

Survivors were M = 61 years old (SD = 9) and predominantly male (75%), White (90%), non-Hispanic (100%), and diagnosed with oropharynx cancer (70%). Providers were mostly female (62%), White (46%) or Asian (31%), and non-Hispanic (85%) and included physicians, registered nurses, an advanced practice nurse practitioner, a registered dietician, and a speech-language pathologist. Three qualitative themes emerged: (1) shock, shame, and self-consciousness, (2) diminished relationship satisfaction, and (3) lack of confidence at work. A subset of survivors (20%) reported clinically low social wellbeing, and more than one-third of survivors (35%) reported clinically significant fatigue, depression, anxiety, and cognitive dysfunction.

Conclusion

Survivors of HNC and HNC providers described how treatment-related symptom burden impacts psychosocial identity processes related to body image, patient-caregiver relationships, and professional work. Results can inform the development of supportive interventions to assist survivors and caregivers with navigating the psychosocial challenges of HNC treatment and survivorship.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data that support this study's findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The data are not publicly available due to privacy concerns.

References

American Cancer Society (2024) Cancer facts & figures 2024. Atlanta: Am Cancer Soc

Machtay M, Moughan J, Trotti A et al (2008) Factors associated with severe late toxicity after concurrent chemoradiation for locally advanced head and neck cancer: an RTOG analysis. J Clin Oncol 26(21):3582–3589. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2007.14.8841

Langendijk JA, Doornaert P, Verdonck-de Leeuw IM, Leemans CR, Aaronson NK, Slotman BJ (2008) Impact of late treatment-related toxicity on quality of life among patients with head and neck cancer treated with radiotherapy. J Clin Oncol 26(22):3770–3776. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2007.14.6647

Rathod S, Livergant J, Klein J, Witterick I, Ringash J (2015) A systematic review of quality of life in head and neck cancer treated with surgery with or without adjuvant treatment. Oral Oncol 51(10):888–900. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oraloncology.2015.07.002

Dunne S, Mooney O, Coffey L et al (2017) Psychological variables associated with quality of life following primary treatment for head and neck cancer: a systematic review of the literature from 2004 to 2015. Psychooncology 26(2):149–160. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4109

Neilson KA, Pollard AC, Boonzaier AM et al (2010) Psychological distress (depression and anxiety) in people with head and neck cancers. Med J Aust 193:S48–S51

Covrig VI, Lazăr DE, Costan VV, Postolică R, Ioan BG (2021) The psychosocial role of body image in the quality of life of head and neck cancer patients. what does the future hold?—A review of the literature. Medicina 57(10):1078

Low C, Fullarton M, Parkinson E et al (2009) Issues of intimacy and sexual dysfunction following major head and neck cancer treatment. Oral Oncol 45(10):898–903

Yu J, Smith J, Marwah R, Edkins O (2022) Return to work in patients with head and neck cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Head Neck 44(12):2904–2924

Kirtane K, Geiss C, Arredondo B et al (2022) “I have cancer during COVID; that’sa special category”: a qualitative study of head and neck cancer patient and provider experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Support Care Cancer 30(5):4337–4344

Oswald LB, Arredondo B, Geiss C et al (2022) Considerations for developing supportive care interventions for survivors of head and neck cancer: a qualitative study. Psychooncology 31(9):1519–1526

Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L (2006) How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Method 18(1):59–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822x05279903

Dueck AC, Mendoza TR, Mitchell SA et al (2015) Validity and reliability of the US National Cancer Institute’s patient-reported outcomes version of the common terminology criteria for adverse events (PRO-CTCAE). JAMA Oncol 1(8):1051–1059

List MA, D’Antonio LL, Cella DF et al (1996) The performance status scale for head and neck cancer patients and the functional assessment of cancer therapy-head and neck scale. A study of utility and validity. Cancer. 77(11):2294–301. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960601)77:11%3c2294::AID-CNCR17%3e3.0.CO;2-S

Pearman T, Yanez B, Peipert J, Wortman K, Beaumont J, Cella D (2014) Ambulatory cancer and US general population reference values and cutoff scores for the functional assessment of cancer therapy. Cancer 120(18):2902–2909. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.28758

Rodriguez AM, Frenkiel S, Desroches J et al (2019) Development and validation of the McGill body image concerns scale for use in head and neck oncology (MBIS-HNC): a mixed-methods approach. Psychooncology 28(1):116–121. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4918

Yellen SB, Cella DF, Webster K, Blendowski C, Kaplan E (1997) Measuring fatigue and other anemia-related symptoms with the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) measurement system. J Pain Symptom Manage 13(2):63–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0885-3924(96)00274-6

Eek D, Ivanescu C, Corredoira L, Meyers O, Cella D (2021) Content validity and psychometric evaluation of the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue scale in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Patient Rep Outcomes 5(1):27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41687-021-00294-1

Piper BF, Cella D (2010) Cancer-related fatigue: definitions and clinical subtypes. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 8(8):958–966. https://doi.org/10.6004/jnccn.2010.0070

Schalet BD, Pilkonis PA, Yu L et al (2016) Clinical validity of PROMIS depression, anxiety, and anger across diverse clinical samples. J Clin Epidemiol 73:119–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.08.036

Cella D, Choi SW, Condon DM et al (2019) PROMIS(®) Adult health profiles: efficient short-form measures of seven health domains. Value Health 22(5):537–544. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2019.02.004

Kroenke K, Stump TE, Chen CX et al (2020) Minimally important differences and severity thresholds are estimated for the PROMIS depression scales from three randomized clinical trials. J Affect Disord 266:100–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.01.101

Cella D, Choi S, Garcia S et al (2014) Setting standards for severity of common symptoms in oncology using the PROMIS item banks and expert judgment. Qual Life Res 23(10):2651–2661. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-014-0732-6

Rothrock NE, Cook KF, O’Connor M, Cella D, Smith AW, Yount SE (2019) Establishing clinically-relevant terms and severity thresholds for Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System® (PROMIS®) measures of physical function, cognitive function, and sleep disturbance in people with cancer using standard setting. Quality of Life Research 28(12):3355–3362. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-019-02261-2

Guest G, MacQueen KM, Namey EE (2011) Applied thematic analysis. sage publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483384436

Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J (2007) Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 19(6):349–357

Charmaz K (1983) Loss of self: a fundamental form of suffering in the chronically ill. Sociol Health Illn 5(2):168–195. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.ep10491512

Gibson C, O’Connor M, White R, Jackson M, Baxi S, Halkett GK (2021) ‘I didn’t even recognise myself’: survivors’ experiences of altered appearance and body image distress during and after treatment for head and neck cancer. Cancers 13(15):3893. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13153893

Freysteinson WM (2020) Demystifying the mirror taboo: a neurocognitive model of viewing self in the mirror. Nurs Inq 27(4):e12351

Hodges LJ, Humphris GM, Macfarlane G (2005) A meta-analytic investigation of the relationship between the psychological distress of cancer patients and their carers. Soc Sci Med 60(1):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.04.018

Hodgkinson K, Butow P, Hunt GE, Wyse R, Hobbs KM, Wain G (2007) Life after cancer: couples’ and partners’ psychological adjustment and supportive care needs. Support Care Cancer 15(4):405–415. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-006-0148-0

Johnson HA, Zabriskie RB, Hill B (2006) The contribution of couple leisure involvement, leisure time, and leisure satisfaction to marital satisfaction. Marriage Fam Rev 40(1):69–91

Badr H, Herbert K, Reckson B, Rainey H, Sallam A, Gupta V (2016) Unmet needs and relationship challenges of head and neck cancer patients and their spouses. J Psychosoc Oncol 34(4):336–346

Isaksson J, Wilms T, Laurell G, Fransson P, Ehrsson YT (2016) Meaning of work and the process of returning after head and neck cancer. Support Care Cancer 24:205–213

Rasmussen DM, Elverdam B (2008) The meaning of work and working life after cancer: an interview study. Psychooncology 17(12):1232–1238

Nguyen OT, Donato U, McCormick R et al (2023) Financial toxicity among head and neck cancer patients and their caregivers: a cross-sectional pilot study. Laryngoscope Investigative Otolaryngology 8(2):450–457

Rosi-Schumacher M, Patel S, Phan C, Goyal N (2023) Understanding financial toxicity in patients with head and neck cancer: a systematic review. Clinical Medicine Insights: Oncology 17:11795549221147730

Acknowledgements

We thank Ms. Kelsey Scheel for her support conducting this study and the survivors and providers who participated.

Funding

This work was supported in part by a Moffitt Cancer Center Innovation Award (MPIs: Oswald, Kirtane), Moffitt’s Participant Research, Interventions, and Measurement (PRISM) Core, and a National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support Grant (P30CA076292).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: CG, AH, KK, LO; Formal analysis: CG, AH, BA, LO; Investigation: CB, LO; Resources: CC, KP, KK; Data curation: CG, AH, BA; Supervision: BH, HJ, KK, LO; Project administration: YR; Funding acquisition: KK, LO; Writing - original draft: CG, AH, KK, LO; Writing - review & editing: All authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Dr. Chung receives honoraria from Sanofi and Exelexis for ad hoc Scientific Advisory Board participation. Dr. Gonzalez is a paid consultant for SureMed compliance and KemPharm, and an advisory board member for Elly Health, Inc outside of this work. Dr. Jim is a paid consultant for RedHill BioParma, Janssen Scientific Affairs, and Merck and has grant funding from Kite Pharma outside of this work. Dr. Kirtane owns stock in Seattle Genetics, Oncternal Therapeutics, and Veru. The other authors have no other relevant competing interests to disclose.

Ethics approval

The current research was reviewed by the Institutional Review Board at Advarra and determined to be exempt from oversight due to minimal risk (Pro00045231). All aspects of this study were conducted in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and later amendments.

Consent to participate

All participants provided verbal consent prior to study enrollment.

Consent for publication

Participants provided verbal consent to have de-identified data published.

Conflict of interest

Dr. Chung receives honoraria from Sanofi and Exelixis for ad hoc scientific advisory board participation. Dr. Gonzalez is a paid consultant for Sure Med Compliance and KemPharm, and an advisory board member for Elly Health, Inc., outside of this work. Dr. Jim is a paid consultant for RedHill Biopharma, Janssen Scientific Affairs, and Merck and has grant funding from Kite Pharma outside of this work. Dr. Kirtane owns stock in Seattle Genetics, Oncternal Therapeutics, and Veru. The other authors have no other relevant competing interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Geiss, C., Hoogland, A.I., Arredondo, B. et al. Psychosocial consequences of head and neck cancer symptom burden after chemoradiation: a mixed-method study. Support Care Cancer 32, 254 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-024-08424-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-024-08424-3