Abstract

Purpose

Aromatase inhibitors (AIs) prolong survival for postmenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer (HR + BC) but also burden patients with symptoms, a major reason for suboptimal AI adherence. This study characterizes inter-relationships among symptom measures; describes neuropsychological symptom burden trajectories; and identifies trajectory group membership predictors for postmenopausal women prescribed anastrozole for HR + BC.

Methods

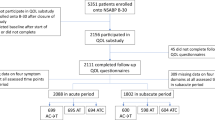

This study utilized prospectively collected data from a cohort study. Relationships among various self-reported symptom measures were examined followed by a factor analysis to reduce data redundancy before trajectory analysis. Four neuropsychological scales/subscales were rescaled (range 0–100) and averaged into a neuropsychological symptom burden (NSB) score, where higher scores indicated greater symptom burden. Group-based trajectory modeling characterized NSB trajectories. Trajectory group membership predictors were identified using multinomial logistic regression.

Results

Women (N = 360) averaged 61 years old, were mostly White, and diagnosed with stage I HR + BC. Several measures were correlated temporally but four neuropsychological measures had strong correlations and dimensional loadings. These four measures, combined for the composite NSB, averaged (mean ± standard deviation) 17.4 ± 12.9, 18.0 ± 12.7, 19.5 ± 12.8, and 19.8 ± 13.0 at pre-anastrozole, 6, 12, and 18 months post-initiation, respectively. However, the analysis revealed five NSB trajectories—low-stable, low-increasing, moderate-stable, high-stable, and high-increasing. Younger age and baseline medication categories (pre-anastrozole), including anti-depressants, analgesics, anti-anxiety, and no calcium/vitamin D, predicted the higher NSB trajectories.

Conclusion

This study found relationships among neuropsychological symptom measures and distinct trajectories of self-reported NSB with pre-anastrozole predictors. Identifying symptom trajectories and their predictors at pre-anastrozole may inform supportive care strategies via symptom management interventions to optimize adherence for women with HR + BC.

© 2009–2021 RStudio, PBC "Tiger Daylily" (2389bc24, 2021–02-11) for macOS

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Please contact corresponding author for data information.

Code availability

N/A.

References

Howlader N, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review 1975–2016. 2019 April 2019 [cited 2019 September 24]; based on November 2018 SEER data submission]. Available from: https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2016/.

Howlader N et al (2018) Differences in breast cancer survival by molecular subtypes in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 27(6):619–626

Miller KD et al (2019) (2019) Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 69(5):363–385

Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative G (2015) Aromatase inhibitors versus tamoxifen in early breast cancer: patient-level meta-analysis of the randomised trials. Lancet 386(10001):1341–1352

Desta Z et al (2009) Antiestrogen pathway (aromatase inhibitor). Pharmacogenet Genomics 19(7):554–555

Anastrozole (2021) IBM Micromedex ® (electronic version) Truven Health Analytics, Inc. Ann Arbor, MI. https://www-micromedexsolutionscom.pitt.idm.oclc.org/micromedex2/librarian/CS/C549B7/ND_PR/evidencexpert/ND_P/evidencexpert/DUPLICATIONSHIELDSYNC/C0DC6D/ND_PG/evidencexpert/ND_B/evidencexpert/ND_AppProduct/evidencexpert/ND_T/evidencexpert/PFActionId/evidencexpert.DoIntegratedSearch?SearchTerm=anastrozole&UserSearchTerm=anastrozole&SearchFilter=filterByDrugHome&navitem=searchDrug#. Accessed 1 June 2021

Marsden J et al (2019) British Menopause Society consensus statement on the management of estrogen deficiency symptoms, arthralgia and menopause diagnosis in women treated for early breast cancer. Post Reprod Health 25(1):21–32

Murphy CC et al (2012) Adherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy among breast cancer survivors in clinical practice: a systematic review. Breast Cancer Res Treat 134(2):459–478

Sawesi S, Carpenter JS, Jones J (2014) Reasons for nonadherence to tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors for the treatment of breast cancer: a literature review. Clin J Oncol Nurs 18(3):E50–E57

Aiello Bowles EJ et al (2012) Patient-reported discontinuation of endocrine therapy and related adverse effects among women with early-stage breast cancer. J Oncol Pract 8(6):e149–e157

Li H et al (2020) Symptom clusters in women with breast cancer during the first 18 months of adjuvant therapy. J Pain Symptom Manage 59(2):233–241

Beckwee D et al (2017) Prevalence of aromatase inhibitor-induced arthralgia in breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer 25(5):1673–1686

Zhu Y, Cohen SM, Rosenzweig MQ, Bender CM (2019) Symptom Map of Endocrine Therapy for Breast Cancer: A Scoping Review Cancer nursing 42:E19–e30. https://doi.org/10.1097/ncc.0000000000000632

Kyvernitakis I et al (2014) Prevalence of menopausal symptoms and their influence on adherence in women with breast cancer. Climacteric 17(3):252–259

Hershman DL et al (2015) Randomized Multicenter placebo-controlled trial of omega-3 fatty acids for the control of aromatase inhibitor-induced musculoskeletal pain: SWOG S0927. J Clin Oncol 33(17):1910–1917

Lintermans A et al (2014) A prospective assessment of musculoskeletal toxicity and loss of grip strength in breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant aromatase inhibitors and tamoxifen, and relation with BMI. Breast Cancer Res Treat 146(1):109–116

Wouters H et al (2014) Endocrine therapy for breast cancer: assessing an array of women’s treatment experiences and perceptions, their perceived self-efficacy and nonadherence. Clin Breast Cancer 14(6):460-467e2

Sini V et al (2017) Pharmacogenetics and aromatase inhibitor induced side effects in breast cancer patients. Pharmacogenomics 18(8):821–830

Schover LR et al (2014) Sexual problems during the first 2 years of adjuvant treatment with aromatase inhibitors. J Sex Med 11(12):3102–3111

Merriman JD et al (2010) Predictors of the trajectories of self-reported attentional fatigue in women with breast cancer undergoing radiation therapy. Oncol Nurs Forum 37(4):423–432

Merriman JD et al (2017) Trajectories of self-reported cognitive function in postmenopausal women during adjuvant systemic therapy for breast cancer. Psychooncol 26(1):44–52

Nagin DS, Odgers CL (2010) Group-Based Trajectory Modeling (Nearly) Two Decades Later. J Quant Criminol 26(4):445–453

Nagin DS (2014) Group-based trajectory modeling: an overview. Ann Nutr Metab 65(2–3):205–210

Bender CM et al (2015) Patterns of change in cognitive function with anastrozole therapy. Cancer 121(15):2627–2636

Stanton A, Bernaards CA, Ganz PA (2005) The BCPT Symptom Scales: a measure of physical symptoms for women diagnosed with ar at risk for breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 97(6):448–456

Daut RL, Cleeland CS, Flanery RC (1983) Development of the Wisconsin Brief Pain Questionnaire to assess pain in cancer and other diseases. Pain 17(2):197–210

McNair D, Lorr M, Droppleman LF (1992) Profile of Mood States Manual: Educational and Industrial Testing Service. Multi-Health Systems Inc, San Diego

Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK (1996) Manual for Beck Depression Inventory-II. Psychological Corporation, San Antonio

Buysse DJ et al (1989) The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res 28(2):193–213

Johns MW (1991) A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep 14(6):540–545

Barrera M Jr, Caples H, Tein JY (2001) The psychological sense of economic hardship: measurement models, validity, and cross-ethnic equivalence for urban families. Am J Community Psychol 29(3):493–517

Ganz PA et al (1995) Base-line quality-of-life assessment in the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project Breast Cancer Prevention Trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 87(18):1372–1382

Terhorst L et al (2011) Evaluation of the psychometric properties of the BCPT Symptom Checklist with a sample of breast cancer patients before and after adjuvant therapy. Psychooncol 20(9):961–968

Norcross JC, Guadagnoli E, Prochaska JO (1984) Factor structure of the Profile of Mood States (POMS): two partial replications. J Clin Psychol 40(5):1270–1277

Baker F, Denniston M, Zabora J, Polland A, Dudley WN (2002) A POMS short form for cancer patients: psychometric and structural evaluation. Psycho-Oncology 11:273–281. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.564

Sprinkle SD et al (2002) Criterion validity, severity cut scores, and test-retest reliability of the Beck Depression Inventory-II in a university counseling center sample. J Couns Psychol 49(3):381–385

Jones BL, Nagin DS, Roeder K (2001) A SAS procedure based on mixture models for estimating developmental trajectories. Sociol Methods Res 29(3):374–393

Whisenant M et al (2019) Symptom trajectories are associated with co-occurring symptoms during chemotherapy for breast cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage 57(2):183–189

Dos Santos M et al (2019) Impact of anxio-depressive symptoms and cognitive function on oral anticancer therapies adherence. Support Care Cancer 27(9):3573–3581

Martino G et al (2020) Quality of life and psychological functioning in postmenopausal women undergoing aromatase inhibitor treatment for early breast cancer. PLoS ONE 115:e0230681. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0230681

Maass SW et al (2015) The prevalence of long-term symptoms of depression and anxiety after breast cancer treatment: a systematic review. Maturitas 82(1):100–108

Dunn LB et al (2011) Identification of distinct depressive symptom trajectories in women following surgery for breast cancer. Health Psychol 30(6):683–692

Bender CM et al (2018) Trajectories of cognitive function and associated phenotypic and genotypic factors in breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 45(3):308–326

Miaskowski C et al (2015) Latent class analysis reveals distinct subgroups of patients based on symptom occurrence and demographic and clinical characteristics. J Pain Symptom Manage 50(1):28–37

Kemp-Casey A et al (2017) Switching between endocrine therapies for primary breast cancer: Frequency and timing in Australian clinical practice. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol 13(2):e161–e170

Wang J et al (2013) Indications of clinical and genetic predictors for aromatase inhibitors related musculoskeletal adverse events in Chinese Han women with breast cancer. PLoS ONE 8:e68798. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0068798

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the women who participated in this research.

Funding

Parent study funding was from the National Cancer Institute R01CA107408 (PI: Bender) and Oncology Nursing Foundation (PI: Bender). This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute F99/K00 F99CA253771 (PI: McCall); the Rockefeller University Heilbrunn Family Center for Research Nursing through the generosity of the Heilbrunn Family; the American Cancer Society Doctoral Degree Scholarship in Cancer Nursing (DSCN-19- 049); the Oncology Nursing Foundation Research Doctoral Scholarship; and the University of Pittsburgh School of Nursing Undergraduate Research Mentorship Program (URMP).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Data preparation was performed by M. McCall, S. Snader, A. Lavanchy, and S. Sereika. Analyses were performed by M. McCall and S. Sereika. The first draft of the manuscript was written by M. McCall with assistance from S. Snader and A. Lavanchy. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

All procedures performed in studies involving participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board approval for the parent study as well as this study. The protocol number for this study is STUDY19050318.

Consent to participate

All participants provided their informed consent obtained by study personnel from the parent study prior to any data collection.

Consent for publication

N/A

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Material in this article is reprinted from Maura K. McCall's dissertation with permission; dissertation available at McCall, Maura Kindelan (2022). Genotypic and Phenotypic Predictors of Cancer Therapy Adherence and Symptom Trajectories in Women with Breast Cancer. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Pittsburgh. (Unpublished) http://d-scholarship.pitt.edu/43604/.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

McCall, M.K., Sereika, S.M., Snader, S. et al. Trajectories of neuropsychological symptom burden in postmenopausal women prescribed anastrozole for early-stage breast cancer. Support Care Cancer 30, 9329–9340 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-022-07326-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-022-07326-6