Abstract

Purpose

To outline the association between race/ethnicity and poverty status and perceived anxiety and depressive symptomologies among BRCA1/2-positive United States (US) women to identify high-risk groups of mutation carriers from medically underserved backgrounds.

Methods

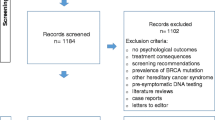

A total of 211 BRCA1/2-positive women from medically underserved backgrounds were recruited through national Facebook support groups and completed an online survey. Adjusted odds ratios (aOR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated using multivariable logistic regression for associations between race/ethnicity, poverty status, and self-reported moderate-to-severe anxiety and depressive symptoms.

Results

Women ranged in age (18–75, M = 39.5, SD = 10.6). Most women were non-Hispanic white (NHW) (67.2%) and were not impoverished (76.7%). Hispanic women with BRCA1/2 mutations were 6.11 times more likely to report moderate-to-severe anxiety (95% CI, 2.16–17.2, p = 0.001) and 4.28 times more likely to report moderate-to-severe depressive symptoms (95% CI, 1.98–9.60, p < 0.001) than NHW women with these mutations. Associations were not statistically significant among other minority women. Women living in poverty were significantly less likely to report moderate-to-severe depressive symptoms than women not in poverty (aOR, 0.42, 95% CI, 0.18–0.95, p = 0.04).

Conclusion

Hispanic women with BRCA1/2 mutations from medically underserved backgrounds are an important population at increased risk for worse anxiety and depressive symptomology. Our findings among Hispanic women with BRCA1/2 mutations add to the growing body of literature focused on ethnic disparities experienced across the cancer control continuum.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed the current study are available at the Principal Investigator’s (PI) discretion upon reasonable request.

Code availability

Syntax coding is available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- aOR:

-

Adjusted odds ratio

- BRCA:

-

BReast CAncer gene mutation

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- NHW:

-

Non-Hispanic white

- US:

-

United States

References

American Cancer Society (ACS) (2020). Family cancer syndromes. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/cancer-causes/genetics/family-cancer-syndromes.html.

Godet I, Gilkes DM (2017) BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations and treatment strategies for breast cancer. Integr Cancer Sci Ther 4(1):10. https://doi.org/10.15761/ICST.1000228

Mersch J, Jackson MA, Park M et al (2015) Cancers associated with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations other than breast and ovarian. Cancer 121(14):269–275. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.29357

Kuchenbaecker KB, Hopper JL, Barnes DR et al (2017) Risks of breast, ovarian, and contralateral breast cancer for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. JAMA 317(23):2402–2416. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.7112

Song Y, Barry WT, Seah DS et al (2020) Patterns of recurrence and metasasis in BRCA1/BRCA2-associated breast cancers. Cancer 126(2):271–280. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.32540

Haque R, Shi JM, Telford C, et al (2018) Survival outcomes in BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carriers and the influence of triple-negative breast cancer subtype. Perm J 22:170–197. https://doi.org/10.7812/TPP/17-197

Lafourcade A, His M, Baglietto L et al (2018) Factors associated with breast cancer recurrences or mortality and dynamic prediction of death using history of cancer recurrences: the French E3N cohort. BMC Cancer 18(1):171. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-018-4076-4

Mau C, Untch M (2017) Prophylactic surgery: for whom, when and how. Breast Care 12:379–384. https://doi.org/10.1159/000485830

Ludwig KK, Neuner J, Butler A, Geurts JL, Kong AL (2016) Risk reduction and survival benefit of prophylactic surgery in BRCA mutation carriers, a systematic review. Am J Surg 212(4):660–669. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2016.06.010

van Zelst JCM, Mus RDM, Woldringh G et al (2017) Surveillance of women with the BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation by using biannual automated breast US, MR imaging, and mammography. Radiol 285(2):376–388. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2017161218

Glassey R, O’Connor M, Ives A et al (2018) Heightened perception of breast cancer risk in young women at risk of familial breast cancer. Fam Cancer 17:15–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10689-017-0001-2

Ringwald J, Wochnowski C, Bosse K et al (2016) Psychological distress, anxiety, and depression of cancer-affected BRCA1/2 mutation carriers: a systematic review. J Genet Couns 25(5):880–891. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10897-016-9949-6

Harmsen MG, Hermens RPMG, Prins JB, Hoogerbrugge N, de Hullu JA (2015) How medical choices influence quality of life of women carrying a BRCA mutation. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 96(3):555–568. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2015.07.010

Manoukian S, Alfieri S, Bianchi E et al (2019) Risk-reducing surgery in BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation carriers: are there factors associated with the choice? Psycho-Oncol 28(9):1871–1878. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5166

Borreani C, Manoukian S, Bianchi E et al (2013) The psychological impact of breast and ovarian cancer preventive options in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. Clin Genet 85(1):7–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/cge.12298

Dean M, Scherr CL, Clements M et al (2017) “When information is not enough”: a model for understanding BRCA-positive previvors’ information needs regarding hereditary breast and ovarian cancer risk. Patient Educ Couns 100(9):1738–1743. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2017.03.013

Hoberg-Vetti H, Bjorvatn C, Fiane BE et al (2016) BRCA1/2 testing in newly diagnosed breast and ovarian cancer patients without prior genetic counseling: the DNA-BONus study. Eur J Hum Genet 24(6):881–888. https://doi.org/10.1038/ejhg.2015.196

Mella S, Muzzatti B, Dolcetti R, Annunziata MA (2017) Emotional impact on the results of BRCA1 and BRCA2 genetic test: an observational retrospective study. Hered Cancer Clin Pract 15:16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13053-017-0077-6

den Heijer M, Seynaeve C, Vanheusden K et al (2012) Long-term psychological distress in women at risk for hereditary breast cancer adhering to regular surveillance: a risk profile. Psycho-Oncol 22(3):598–604. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3039

Cannioto R (2020) Investigating contributions of physical inactivity and obesity to racial disparities in cancer risk and mortality warrants more consideration. J Natl Cancer Inst 113(6):647–649. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djaa189

Williams CD, Bullard AJ, O’Leary M, Thomas R, Redding TS IV, Goldstein K (2019) Racial/ethnic disparities in BRCA counseling and testing: a narrative review. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities 6(3):570–583. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-018-00556-7

Jones T, Freeman K, Ackerman M et al (2020) Mental illness and BRCA1/2 genetic testing intention among multiethnic women undergoing screening mammography. Oncol Nurs Forum 47(1):E13–E24. https://doi.org/10.1188/20.onf.e13-e24

Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL et al (2019) The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform 95:103208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208

US Census Bureau (2020). How the Census Bureau measures poverty. https://www.census.gov/topics/income-poverty/poverty/guidance/poverty-measures.html.

Lowe B, Decker O, Muller S et al (2008) Validation and standardization of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Med Care 46(3):266–274. https://doi.org/10.1097/mlr.0b013e318160d093

Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW (2006) A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 166(10):1092–1097. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW (2001) The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 16(9):606–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

StataCorp, Inc (2019). Stata Statistical Software: Release 16. College Station, TX.

Nelson HD, Pappas M, Cantor A, Haney E, Holmes R (2019) Risk assessment, genetic counseling, and genetic testing for BRCA-related cancer in women: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA 322(7):666–685. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.8430

Yeomans Kinney A, Gammon A, Coxworth J et al (2010) Exploring attitudes, beliefs, and communication preferences of Latino community members regarding BRCA1/2 mutation testing and preventive strategies. Genet Med 12(2):105–115. https://doi.org/10.1097/gim.0b013e3181c9af2d

Parente DJ (2020) BRCA-related cancer genetic counseling is indicated in many women seeking primary care. J Am Board Fam Med 33(6):885–893. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2020.06.190461

Thompson HS, Sussner K, Schwartz MD et al (2012) Receipt of genetic counseling recommendations among black women at high risk for BRCA mutations. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers 16(11):1257–1262. https://doi.org/10.1089/gtmb.2012.0114

Levy DE, Byfield SD, Comstock CB et al (2011) Underutilization of BRCA1/2 testing to guide breast cancer treatment: Black and Hispanic women particularly at risk. Genet Med 13(4):349–355. https://doi.org/10.1097/gim.0b013e3182091ba4

McGuinness JE, Trivedi MS, Silverman T et al (2019) Uptake of genetic testing for germline BRCA1/2 pathogenic variants in a predominantly Hispanic population. Cancer Genet 235–236:72–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cancergen.2019.04.063

Lagos-Jaramillo VI, Press MF, Ricker CN, et al (2011) Pathological characteristics of BRCA-associated breast cancers in Hispanics. Breast Cancer Res Treat 130(1):281–289. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-011-1570-7

Hull LE, Haas JS, Simon SR (2018) Provider discussions of genetic tests with U.S. women at right for a BRCA mutation. Am J Prev Med 54(2):221–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2017.10.015

Guo F, Scholl M, Fuchs EL, et al (2020). Trends in positive BRCA test results among older women in the United States, 2008–2018. JAMA Network Open, 3(11):e2024358. http://jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?doi=https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.24358

Moses T, Landefeld R (2019). Addressing behavioral health and cancer in Hispanic/Latino populations. https://www.bhthechange.org/resources/addressing-behavioral-health-and-cancer-in-hispanic-latino-populations/.

Rubinsak LA, Kleinman A, Quillin J et al (2019) Awareness and acceptability of population-based screening for pathogenic BRCA variants: do race and ethnicity matter? Gynecol Oncol 154(2):383–387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2019.06.009

Hurtado-de-Mendoza A, Graves K, Gomez-Trillos S et al (2018) Provider’s perceptions of barriers and facilitators for Latinas to participate in genetic cancer risk assessment for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. Healthcare 6(3):116. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare6030116

Sussner KM, Jandorf L, Thompson HS, Valdimarsdottir HB (2013) Barriers and facilitators to BRCA genetic counseling among at-risk Latinas in New York City. Psycho-Oncol 22(7):1594–1604. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3187

Sussner KM, Edwards T, Villagra C, et al (2010) Interest and beliefs about BRCA genetic counseling among at-risk Latinas in New York City. J Genet Couns 19(3):255–268. https://doi.org/10.1007/2Fs10897-014-9746-z

Augusto B, Kasting ML, Couch FJ et al (2019) Current approaches to cancer genetic counseling services for Spanish-speaking patients. J Immigr Minor Health 21(2):434–437. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-018-0772-z

Trottier M, Lunn J, Butler R et al (2015) Strategies for recruitment of relatives of BRCA mutation carriers to a genetic testing program in the Bahamas. Clin Genet 88(2):182–186. https://doi.org/10.1111/cge.12468

Houlihan MC, Tariman JD (2017). Comparison of outcome measures for traditional and online support groups for breast cancer patients: an integrative literature review. J Adv Pract Oncol 8(4): 348–359. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6040879

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the women who shared their experiences with us.

Funding

This work was supported by the Johns Hopkins Ho-Ching Wang Memorial Faculty Award. Kate E Dibble received research support from the National Cancer Institute (T32CA009314) Cancer Epidemiology, Prevention, and Control training program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Kate E Dibble conceptualized and designed the study, was in charge of data acquisition, data analysis, and interpretation. Kate E Dibble also wrote the main manuscript text and revised the article, as well as approving the final version. Avonne E Connor assisted with study conceptualization and design, data interpretation, as well as drafting and finalizing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Institutional Review Board (IRB#00013710).

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dibble, K.E., Connor, A.E. Anxiety and depression among racial/ethnic minorities and impoverished women testing positive for BRCA1/2 mutations in the United States. Support Care Cancer 30, 5769–5778 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-022-07004-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-022-07004-7