Abstract

Background

Fatigue, pain, and anxiety, symptoms commonly experienced by children with cancer, may predict pediatric symptom suffering profile membership that is amenable to treatment.

Methods

Three latent profiles (Low, Medium, and High symptom suffering) from 436 pediatric patients undergoing cancer care were assessed for association with three single-item symptoms and socio-demographic variables.

Results

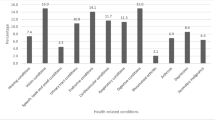

Pediatric-PRO-CTCAE fatigue, pain, and anxiety severity scores at baseline were highly and significantly associated with the Medium and High Suffering profiles comprised of PROMIS pediatric symptom and function measures. The likelihood of membership in the Medium Suffering group was 11.37 times higher for patients who experienced fatigue severity than those with did not, while experience of pain severity increased the likelihood of the child’s membership in the Medium Suffering profile by 2.59 times and anxiety by 3.67 times. The severity of fatigue increased the likelihood of presence in the High Suffering group by 2.99 times while pain severity increased the likelihood of the child’s membership in the High Suffering profile by 6.36 times and anxiety by 16.75 times. Controlling for experience of symptom severity, older patients were more likely to be in the Higher or Medium Suffering profile than in the Low Suffering profile; no other socio-demographic or clinical variables had a significant effect on the latent profile classification.

Conclusion

Clinician knowledge of the strong association between fatigue, pain, and anxiety severity and suffering profiles may help focus supportive care to improve the cancer experience for children most at risk from time of diagnosis through treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Data are available upon request from senior author.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Dupuis LL et al (2010) Symptom assessment in children receiving cancer therapy: the parents’ perspective. Support Care Cancer 18(3):281–299

Enskar K, von Essen L (2007) Prevalence of aspects of distress, coping, support and care among adolescents and young adults undergoing and being off cancer treatment. Eur J Oncol Nurs 11(5):400–408

Ye ZJ et al (2019) Symptoms and management of children with incurable cancer in mainland China. Eur J Oncol Nurs 38:42–49

Friedrichsdorf SJ, Postier AC (2019) Recent advances in pain treatment for children with serious illness. Pain Manag 9(6):583–596

Twycross A et al (2015) Cancer-related pain and pain management: sources, prevalence, and the experiences of children and parents. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 32(6):369–384

Miser AW et al (1987) The prevalence of pain in a pediatric and young adult cancer population. Pain 29(1):73–83

Nunes MDR et al (2019) Pain, sleep patterns and health-related quality of life in paediatric patients with cancer. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 28(4):e13029

Schlegelmilch M, et al (2019) Observational study of pediatric inpatient pain, nausea/vomiting and anxiety. Children (Basel) 6(5)

Cheng L et al (2018) Perspectives of children, family caregivers, and health professionals about pediatric oncology symptoms: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer 26(9):2957–2971

Leahy AB, Feudtner C, Basch E (2018) Symptom monitoring in pediatric oncology using patient-reported outcomes: why, how, and where next. Patient 11(2):147–153

Huang IC et al (2018) Child symptoms, parent behaviors, and family strain in long-term survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Psychooncology 27(8):2031–2038

Baggott C et al (2009) Multiple symptoms in pediatric oncology patients: a systematic review. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 26(6):325–339

Walsh D, Rybicki L (2006) Symptom clustering in advanced cancer. Support Care Cancer 14(8):831–836

Hinds PS, et al (2020) Subjective toxicity profiles of children in treatment for cancer: a new guide to supportive care? J Pain Symptom Manage

Buckner TW et al (2014) Patterns of symptoms and functional impairments in children with cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer 61(7):1282–1288

Wang J et al (2018) A longitudinal study of PROMIS Pediatric Symptom clusters in children undergoing chemotherapy. J Pain Symptom Manage 55(2):359–367

Hinds PS et al (2019) PROMIS pediatric measures validated in a longitudinal study design in pediatric oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer 66(5):e27606

Yeh CH et al (2008) Symptom clustering in older Taiwanese children with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 35(2):273–281

Reeve BB et al (2020) Validity and reliability of the pediatric patient-reported outcomes version of the common terminology criteria for adverse events. J Natl Cancer Inst 112(11):1143–1152

McFatrich M et al (2020) Mapping child and adolescent self-reported symptom data to clinician-reported adverse event grading to improve pediatric oncology care and research. Cancer 126(1):140–147

Reeve BB, et al (2017) Eliciting the child's voice in adverse event reporting in oncology trials: cognitive interview findings from the Pediatric Patient-Reported Outcomes version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events initiative. Pediatr Blood Cancer 64(3)

Hinds PS et al (2021) Subjective toxicity profiles of children in treatment for cancer: a new guide to supportive care? J Pain Symptom Manage 61(6):1188-1195 e2

Withycombe JS et al (2019) The association of age, literacy, and race on completing patient-reported outcome measures in pediatric oncology. Qual Life Res 28(7):1793–1801

Feldman BJ, Masyn KE, Conger RD (2009) New approaches to studying problem behaviors: a comparison of methods for modeling longitudinal, categorical adolescent drinking data. Dev Psychol 45(3):652–676

Lanza ST, Collins LM (2006) A mixture model of discontinuous development in heavy drinking from ages 18 to 30: the role of college enrollment. J Stud Alcohol 67(4):552–561

McArdle J (2004) Latent growth curve analyses using structural equation modeling techniques. In: Teti D (ed) Handbook of research methods in developmental science. Blackwell, Malden, MA, pp 340–366

Vermunt J (2010) Latent class modeling with covariates: two improved three-step approaches. Polit Anal 18:450–469

Asparouhov T, Muthén B (2014) Auxiliary variables in mixture modeling. Struct Equ Model A Multidiscip J 21:329–341

Montgomery KE et al (2020) Comparison of child self-report and parent proxy-report of symptoms: results from a longitudinal symptom assessment study of children with advanced cancer. J Spec Pediatr Nurs e12316

Mack JW et al (2020) Agreement between child self-report and caregiver-proxy report for symptoms and functioning of children undergoing cancer treatment. JAMA Pediatr 174(11):e202861

Pinheiro LC et al (2018) Child and adolescent self-report symptom measurement in pediatric oncology research: a systematic literature review. Qual Life Res 27(2):291–319

Leahy AB, Steineck A (2020) Patient-reported outcomes in pediatric oncology: the patient voice as a gold standard. JAMA Pediatr 174(11):e202868

Weaver MS et al (2016) Concept-elicitation phase for the development of the pediatric patient-reported outcome version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events. Cancer 122(1):141–148

Williams PD et al (2012) A symptom checklist for children with cancer: the therapy-related symptom checklist-children. Cancer Nurs 35(2):89–98

Dodd MJ, Miaskowski C, Lee KA (2004) Occurrence of symptom clusters. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 32:76–78

Docherty SL (2003) Symptom experiences of children and adolescents with cancer. Annu Rev Nurs Res 21:123–149

Madden K et al (2019) Systematic symptom reporting by pediatric palliative care patients with cancer: a preliminary report. J Palliat Med 22(8):894–901

Hockenberry MJ et al (2011) Sickness behavior clustering in children with cancer. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 28(5):263–272

Baggott C et al (2012) Symptom cluster analyses based on symptom occurrence and severity ratings among pediatric oncology patients during myelosuppressive chemotherapy. Cancer Nurs 35(1):19–28

Atay S, Conk Z, Bahar Z (2012) Identifying symptom clusters in paediatric cancer patients using the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 21(4):460–468

Hooke MC et al (2018) Physical activity, the childhood cancer symptom cluster-leukemia, and cognitive function: a longitudinal mediation analysis. Cancer Nurs 41(6):434–440

Rostagno E et al (2020) Italian nurses knowledge and attitudes towards fatigue in pediatric onco-hematology: a cross-sectional nationwide survey. Int J Pediatr Adolesc Med 7(4):161–165

Miller E, Jacob E, Hockenberry MJ (2011) Nausea, pain, fatigue, and multiple symptoms in hospitalized children with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 38(5):E382–E393

Eche IJ, Eche IM, Aronowitz T (2020) An integrative review of factors associated with symptom burden at the end of life in children with cancer. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 37(4):284–295

Castelli L, et al (2021) Sleep problems and their interaction with physical activity and fatigue in hematological cancer patients during onset of high dose chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer

Hooke MC, Garwick AW, Gross CR (2011) Fatigue and physical performance in children and adolescents receiving chemotherapy. Oncol Nurs Forum 38(6):649–657

Watling CZ et al (2020) Development of the SPARK family member web pages to improve symptom management for pediatric patients receiving cancer treatments. BMC Cancer 20(1):923

Akel BS et al (2019) Cognitive rehabilitation is advantageous in terms of fatigue and independence in pediatric cancer treatment: a randomized-controlled study. Int J Rehabil Res 42(2):145–151

Lopes-Junior LC et al (2020) Clown intervention on psychological stress and fatigue in pediatric patients with cancer undergoing chemotherapy. Cancer Nurs 43(4):290–299

Govender M et al (2015) Clinical and neurobiological perspectives of empowering pediatric cancer patients using videogames. Games Health J 4(5):362–374

Zupanec S et al (2017) A sleep hygiene and relaxation intervention for children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Cancer Nurs 40(6):488–496

Lai JS et al (2016) A cross-sectional study of carnitine deficiency and fatigue in pediatric cancer patients. Childs Nerv Syst 32(3):475–483

Swartz MC, et al (2019) A narrative review on the potential of red beetroot as an adjuvant strategy to counter fatigue in children with cancer. Nutrients 11(12)

Brown AL et al (2021) Cerebrospinal fluid metabolomic profiles associated with fatigue during treatment for pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Pain Symptom Manage 61(3):464–473

Fortier MA et al (2020) Children’s cancer pain in a world of the opioid epidemic: challenges and opportunities. Pediatr Blood Cancer 67(4):e28124

Dupuis LL et al (2016) Anxiety, pain, and nausea during the treatment of standard-risk childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a prospective, longitudinal study from the Children’s Oncology Group. Cancer 122(7):1116–1125

Thrane S (2013) Effectiveness of integrative modalities for pain and anxiety in children and adolescents with cancer: a systematic review. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 30(6):320–332

Altay N, Kilicarslan-Toruner E, Sari C (2017) The effect of drawing and writing technique on the anxiety level of children undergoing cancer treatment. Eur J Oncol Nurs 28:1–6

Lopez-Rodriguez MM, et al (2020) New technologies to improve pain, anxiety and depression in children and adolescents with cancer: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(10)

Hunter JF et al (2020) A pilot study of the preliminary efficacy of Pain Buddy: a novel intervention for the management of children’s cancer-related pain. Pediatr Blood Cancer 67(10):e28278

Jibb LA, et al (2017) Implementation and preliminary effectiveness of a real-time pain management smartphone app for adolescents with cancer: a multicenter pilot clinical study. Pediatr Blood Cancer 64(10)

Ander M et al (2017) Guided internet-administered self-help to reduce symptoms of anxiety and depression among adolescents and young adults diagnosed with cancer during adolescence (U-CARE: YoungCan): a study protocol for a feasibility trial. BMJ Open 7(1):e013906

Snaman J et al (2020) Pediatric Palliative Care in Oncology. J Clin Oncol 38(9):954–962

Sung L, Miller TP, Phillips R (2020) Improving symptom control and reducing toxicities for pediatric patients with hematological malignancies. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2020(1):280–286

Cook S et al (2020) Feasibility of a randomized controlled trial of symptom screening and feedback to healthcare providers compared with standard of care using the SPARK platform. Support Care Cancer 28(6):2729–2734

Wolfe J et al (2014) Improving the care of children with advanced cancer by using an electronic patient-reported feedback intervention: results from the PediQUEST randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 32(11):1119–1126

Carle AC et al (2021) Using nationally representative percentiles to interpret PROMIS pediatric measures. Qual Life Res 30(4):997–1004

Funding

This study was supported by the National Cancer Institute (R01CA175759) and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (U19AR069522).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Meaghann Weaver, Jichuan Wang, Molly McFatrich, and Pamela Hinds contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by Jichuan Wang and Pamela Hinds. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Meaghann Weaver and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board Approval.

Consent to participate

Freely given, informed consent to participate in the study was obtained from participants (or their parent or legal guardian in the case of children under legal age of majority). Assent was additionally obtained from pediatric-age patients.

Consent for publication

Not applicable. Data de-identified.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Role of funding/support

Dr Weaver contributed to this paper in a private capacity. No official support or endorsement by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs is intended, nor should be inferred.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Weaver, M.S., Wang, J., Greenzang, K.A. et al. The predictive trifecta? Fatigue, pain, and anxiety severity forecast the suffering profile of children with cancer. Support Care Cancer 30, 2081–2089 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06622-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06622-x