Abstract

Purpose

Vaginal atrophy is one of the most common side effects of using tamoxifen in women with breast cancer. Hormone therapy for vaginal atrophy is prohibited in these women. The present study was conducted to investigate the effect of vitamin D and E vaginal suppositories on vaginal atrophy in women with breast cancer receiving tamoxifen.

Methods

Women under breast cancer management receiving tamoxifen and showing symptoms of vaginal atrophy were randomized triple-blind to an 8-week trial on vaginal suppository vitamin E or vitamin D or placebo administered every night before bedtime. The genitourinary atrophy self-assessment tool was administered, and pH was measured in all three groups before the intervention and at the end of weeks 2, 4, and 8 of the intervention. The Vaginal Maturation Index (VMI) was also measured before the intervention and at the end of the eighth week. Data were analyzed with paired t tests, repeated measures analysis of variance, and chi-square test.

Results

Thirty-two patients were randomized in each group. The results obtained showed an increase in the VMI by the end of the eighth week of the intervention in the groups receiving the vitamin D and E vaginal suppositories compared with the placebo group (P < 0.001). The vaginal pH also reduced in both groups compared with that in the placebo group (P < 0.001). The symptoms of self-reported genitourinary atrophy also improved in the two intervention groups compared with those in the placebo group by the end of the eighth week (P < 0.001).

Conclusion

These data support that vitamin D and E vaginal suppositories were beneficial in improving vaginal atrophy in women with breast cancer receiving tamoxifen. Given the prohibition on hormone therapy in these women, the suppositories can be used as an alternative therapy to improve these symptoms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common type of cancer in women and the second leading cause of cancer-related death in women after lung cancer [1]. In Iran, too, breast cancer is the most common cancer diagnosed and the fifth most common cause of death in women. Studies show that the mean age of patients with breast cancer is over 55 in western countries and 10 years less in Iran [2]. The adjuvant treatment of breast cancer, which is a combination of chemotherapy and hormone therapy, can induce symptoms of early menopause by affecting the ovarian reserves and vaginal tissue in women with breast cancer [3]. As a chosen hormone therapy for breast cancer with estrogen receptor positive (ER-positive), tamoxifen is a selective regulator of estrogen receptors that act as estrogen agonist in some body tissues and an antagonist in others, including the breast [4]. With its antiestrogenic effects in the vagina, tamoxifen can cause vaginal atrophy and related sexual problems in premenopausal women. In female rats, tamoxifen creates an estrogen-deficient medium and causes functional changes in the vaginal tissues, which ultimately cause vaginal atrophy, dryness, pain, and sexual dysfunction [5]. The administration of tamoxifen is most beneficial in women younger than 50 with breast cancer and positive estrogen receptors, because this age group is more sexually active than older women, and vaginal atrophy, which is a common complication of this medication, affects their sexual function more severely [1].

By causing changes in the vaginal mucosal membranes and tissues, vaginal atrophy creates symptoms such as burning, itching, vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, dysuria, postcoital bleeding, and frequent urination and urge [6]. Various hormonal and non-hormonal methods have been proposed for improving vaginal atrophy, including estrogen therapy as a highly effective method for improving its symptoms in postmenopausal women, since it plays a major role in the treatment of dyspareunia and vaginal dryness [7]. Alternative hormone therapies can cause complications such as increased risk of endometrial, breast, and ovarian cancer and thromboembolism [8,9,10,11]. Systemic treatment with estrogenic products, which is one of the most effective treatments for vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women, is not generally the right option for breast cancer patients [12], and the harms of systemic hormone therapy outweigh its benefits in these women [13]. Additionally, The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the Endocrine Society, and The North American Menopause Society (NAMS) cautiously support the use of low-dose local hormone therapies for genitourinary symptoms in consultation with the woman’s oncologist to consider the benefits and potential risks in women with ER-positive breast cancers on tamoxifen [14, 15]. Given the discussed points, non-hormonal methods are being recommended as the first line of treatment for vaginal atrophy in women with a prohibition on estrogen [16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. Vitamin D is involved in regulating cell development and differentiation, especially in the stratified epithelium tissue of the vagina, and can increase the maturation of the vaginal cells by affecting vitamin D receptors in the vagina [23, 24]. Lee et al. showed that vitamin D proliferates vaginal epithelium through RhoA expression. The expression of cell-to-cell junction proteins was higher in women with symptoms of atrophic vagina tissue compared with that in women without the symptoms. Vitamin D stimulated the proliferation of the vaginal epithelium by activating p-RhoA and Erzin through the vitamin D receptor (VDR). The results suggested that vitamin D positively regulates cell-to-cell junction by increasing the VDR/p-RhoA/p-Ezrin pathway [25]. Vitamin E also has an anti-inflammatory and antioxidant role and healing properties and can be effective in improving the symptoms of vaginal atrophy. Studies showed that it takes part to the metabolism of all cells and prevents the degradation of the tissue due to oxidant agents [16, 26].

Some preclinical studies support the vitamin D effect on the vaginal epithelium such as Abban et al. study. They showed that treatment with exogenous vitamin D3 in ovariectomized rats led to expression of vitamin D receptor in the superficial layers of the vaginal epithelium [27]. But preclinical studies are not found about vitamin E effect on the vaginal epithelium. Most studies have focused on the oral or vaginal effects of vitamins D and E on postmenopausal vaginal atrophy, and there is a lack of adequate information on the use of this therapy in tamoxifen-induced vaginal atrophy in women with breast cancer [23, 24, 26, 28]. Given that breast cancer affects Iranian women a decade earlier than their western peers, they are more likely to receive tamoxifen and thereby experience complications such as vaginal atrophy. Given that these women are sexually active and since vaginal atrophy causes sexual problems and given the prohibition on the use of estrogen for the treatment of this complication in this group, the present study was conducted to investigate the effects of vitamin D and E vaginal suppositories on tamoxifen-induced vaginal atrophy in women with breast cancer.

Methods

Study design

The present triple-blind, controlled, randomized clinical trial was conducted on women with breast cancer receiving tamoxifen and presenting to Shahid Motahari Breast Clinic affiliated to Shiraz University of Medical Sciences (a referral center in the south of Iran) from October 2016 to July 2017. The research project was approved by the ethics committee of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences (IR.SUMS.REC 94-01-08-11247) and registered at the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT2016100229683N2). Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants.

Patient eligibility

The inclusion criteria consisted of being married, having stage 1 or 2 breast cancer based on the surgery stage, age below 50, receiving tamoxifen, not undergoing chemotherapy or radiotherapy during the study, a normal Pap smear during the last 3 years, no proven malignancies in other parts of the body, being sexually active during the study, meeting at least one of the criteria set in the genitourinary atrophy self-assessment, vaginal pH ≥ 5 according to Chollet et al. study [29] at the time of the study, and a Vaginal Maturation Index (VMI) ≤ 52 according to Speroff’s study [30]. The exclusion criteria consisted of unwillingness to participate in the study, vaginal infection, estrogen therapy in the last 8 weeks, idiopathic vaginal bleeding, and disease recurrence based on the diagnosis recorded in the patient’s file.

Procedures

First, the patients’ details were recorded based on the questionnaire and included their demographic details; pregnancy history; medical history and disease history, including the time of breast cancer diagnosis based on the pathology results and the type and stage of breast cancer; and also the status of tamoxifen administration, including the duration of use at the time of beginning the research and the daily dose used. To verify the subjects in terms of meeting the last three inclusion criteria, the patients who met the other criteria had a speculum inserted into the vagina and a pH strip (Sigma-Aldrich Co., Germany) with a precision of 0.5 placed to touch the depth of the vagina for 1 min. Immediately after removal, changes in the color of the pH strip were compared with those of the reference strip and the vaginal pH was thus recorded. If pH ≥ 5, a sample was taken from the inner and outer cervix by a spatula and placed on a slide for a Pap smear. To assess the VMI, a sample was taken by cytobrush from the vaginal posterior fornix cells and also from the upper-third side walls of the vagina and placed on a slide. Slides were read by one pathologist. The subjective symptoms of vaginal atrophy were assessed according to the 15 criteria set in the genitourinary atrophy self-assessment tool for patients with breast cancer, which has had its validity and reliability confirmed by Lester et al. [31], and were scored based on a 7-point Likert scale (from totally disagree = 1 to totally agree = 7). The tool was assessed symptoms of vaginal atrophy in three areas as following: urologic (burning with urination, urge, leakage, incomplete emptying, nocturnal urination), genital (external irritation, itching, vaginal dryness, odor, vaginal discharge), and sexual (dyspareunia, interest/desire in sexual activity, partner communication, happy with partner).The self-assessment scores ranged from 15 to 105. The patients who had normal Pap smear results, no vaginal infection or cervical malignancies and a confirmed vaginal atrophy with VMI ≥ 52, and at least one of the criteria set in the genitourinary self-assessment tool were contacted over the phone and invited to visit the clinic to take part in the study.

In the first session, a package containing 14 vaginal suppositories and 14 applicators was given to each patient. The patients were instructed on how and when to use the suppositories and told when to next visit the clinic for follow-up. One suppository was to be inserted deep into the vagina by the applicator every day before bedtime. The patients were instructed not to use any oral or vaginal hormones during this time and were asked to visit the clinic in the case of problems or irritation and burning following the use of the suppositories or to contact the numbers given to them. During the study, the patients were contacted on a telephone every 3 days, and in addition to reminding and following up on the use of suppositories, their possible questions were also answered. The dates for the next visits were arranged as follows: the second visit in the second week, the third visit in the fourth week, and the fourth visit in the eighth week of beginning the use of the suppositories. In the second visit, in addition to distributing the next 14 suppositories, the patients’ subjective symptoms of vaginal atrophy were assessed by the 15-point self-assessment tool and their vaginal pH was measured. In the third visit, in addition to distributing the remaining 28 suppositories, the subjective symptoms of vaginal atrophy and pH value were again assessed as in the second visit. In the fourth visit, the subjective symptoms of vaginal atrophy, pH, and VMI were controlled.

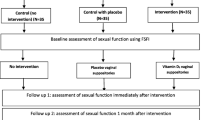

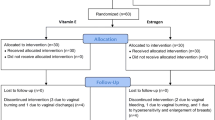

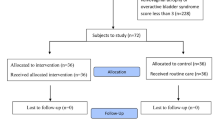

Randomization and intervention

A total of 96 patients were randomly assigned into three groups (Fig. 1) using permuted block randomization. The groups were identified with letters A to C, and each group was given one of the three types of suppositories coded by the manufacturer that contained either vitamin D, vitamin E, or placebo. The researcher, patients, pathologist, and data analysts were blinded to the groupings. The vitamin D, vitamin E, and placebo suppositories were prepared at the School of Pharmacy of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences using the base substance including fatty acid bases (Hard Fat Suppocire AS2) and semi-synthetic glyceride fatty acid (Gattefossé SAS, France). The placebo suppository contained only 2 g of the base substance. The vitamin D suppository contained 2 g of the base substance plus 1000 IU of vitamin D (0.025 mg), and the vitamin E suppository contained 1 mg of vitamin E plus 2 g of the base substance. The suppositories and applicators were put in similar packages and coded by the manufacturer.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed in SPSS-16 using descriptive statistics and the paired t test, the ANOVA, Tukey’s post hoc test, the chi-square test, and the repeated measures ANOVA at the significance level of 0.05.

Results

The results showed no significant differences among the three groups in terms of participants’ demographic details such as age, age at marriage, age at menarche, gravidity, parity, number of abortions, number of living children, body mass index (BMI), education, and occupation (Table 1).

No significant differences were observed among the three groups in terms of the stage of the disease, type of malignancy, and history and frequency of chemotherapy and radiotherapy. The duration of use of tamoxifen varied from 2 to 89 months in the participants, with significant differences observed among the three groups. The vitamin E group had used tamoxifen for a longer period. The difference observed based on Tukey’s post hoc test was only due to the difference between the vitamin E and placebo groups (P = 0.008) (Table 2).

At first, we used repeated measures analysis of covariance (RMANCOVA) for controlling the duration of tamoxifen use (month). Results showed that there was a significant difference between the three groups (P = 0.027). The results obtained showed a significant difference among the three groups in terms of the mean vaginal pH before the intervention. The inter-group comparison in terms of the mean vaginal pH showed a significant difference among the three groups 8 weeks after the intervention. The intra-group comparison of the mean pH also showed significant differences before and after the intervention, and the mean pH reduced by 1.59 units in the vitamin E group and by 1.53 units in the vitamin D group, but increased by 0.04 units in the placebo group (Table 3).

At first, we used repeated measures analysis of covariance (RMANCOVA) for controlling the duration of tamoxifen use (month) on VMI. Results showed that there was a significant difference between the three groups for VMI in superficial and parabasal cells (P ≤ 0.001). But there was no significance in intermediate cells (P = 0.416).

The inter-group comparison of the VMI before the intervention showed no significant differences in terms of the percentage of superficial and parabasal cells, but the difference among the groups was statistically significant at the end of the eighth week of the intervention. The results showed that the mean VMI increased significantly only in the vitamin E and vitamin D groups by the end of the eighth week, and this difference was due to the increase in the mean percentage of superficial cells and the decrease in the mean percentage of parabasal cells in these two groups compared to before the intervention, while no such change was observed in the placebo group. The intra-group comparison of the mean VMI showed significant differences in the percentage of superficial and parabasal cells in the vitamin E and D groups before and after the intervention. The inter- and intra-group comparison of the mean percentage of intermediate cells before and after the intervention showed no significant differences (Table 4).

The inter-group comparison of the mean score of the genitourinary atrophy self-assessment showed no significant differences before the intervention, but the difference was significant at the second, fourth, and eighth weeks of the intervention, which suggests improved subjective symptoms of vaginal atrophy in the vitamin E and D groups on these occasions. The intra-group comparison of the mean score of genitourinary atrophy self-assessment in the three groups showed a significant reduction in the mean score in the vitamin E and D groups compared with that in the placebo group (Table 5).

Discussion

The results showed a significant reduction in the vaginal pH, an increase in the VMI, and improvements in the subjective symptoms of vaginal atrophy with the use of vitamin E and D vaginal suppositories in women with breast cancer using tamoxifen compared with those in the placebo group. Before beginning the study, vaginal pH differed significantly among the three groups, and its mean numerical value was higher in the vitamin E and D groups compared with that in the placebo group, which appears to be due to the longer period of using tamoxifen in these two groups. By the end of the intervention, the mean pH decreased significantly in these two groups compared with that in the placebo group. The significant difference in pH in the placebo group by the end of the study was due to the increase in the mean pH, which suggests the exacerbation of the status of vaginal atrophy due to the longer period of tamoxifen use in this group. By the end of the study, the VMI increased significantly in the vitamin E and D groups compared with that in the placebo group as a result of the increase in superficial cells and the decrease in parabasal cells in these two groups. The descending trend of the mean score of the genitourinary atrophy self-assessment in the vitamin E and D groups compared with that in the placebo group from the second week to the end of the intervention was indicative of a reduction in the symptoms of atrophy in these two groups.

The present findings agree with the results obtained in previous studies on the effect of vitamin E and D on vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women. In a study conducted by Yildirim et al. in Turkey to assess the effect of a daily dose of 0.500 μg of calcitriol for 1 year on vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women, an improvement was observed in the symptoms of vaginal atrophy, the VMI increased and pH decreased; however, this study only assessed the effect of oral vitamin D on the symptoms of vaginal atrophy in physiologically postmenopausal women, while the present study investigated the effect of vitamins E and D on tamoxifen-induced vaginal atrophy in women with breast cancer. The cited study showed a significant difference between the intervention and control groups in terms of the percentage of superficial and parabasal cells, but no significant differences were observed between them in terms of intermediate cells at the end of the intervention. In the present study, too, a significant increase was observed at the end of the intervention in the mean percentage of superficial cells and a significant reduction in the percentage of parabasal cells in the vitamin E and D groups, but no significant changes were observed in the percentage of intermediate cells. Just as the oral vitamin D used in Yildirim’s study, the vitamin D vaginal suppositories used in the present study were able to improve the symptoms of vaginal atrophy [23].

The present results also agree with those obtained in a study conducted by Zeyneloglu et al. in Turkey to assess the effect of a 60-mg daily dose of raloxifene plus 400 IU of oral vitamin D for 3 months on the VMI and genitourinary symptoms in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. Just as in the present study, Zeyneloglu’s study found a significant increase in the VMI in the intervention group, and the changes in the percentage of intermediate and parabasal cells were statistically significant, but the percentage of superficial cells did not change significantly. These findings are only consistent with the present findings in terms of the changes in parabasal cells and are inconsistent in terms of superficial and intermediate cells. Moreover, no significant changes were reported in the patients’ self-reported symptoms such as dyspareunia, urination problems, vaginal burning, and hot flushes, which disagrees with the results of the present study. This disparity of findings could be due to the differences in the causes of vaginal atrophy, type of intervention and method, and dosage of supplements used [28].

The present findings concur with the results obtained in a study conducted by Rad et al. in Iran to assess the effect of a daily dose of 1000 IU of vitamin D in the form of vaginal suppositories for 8 weeks on vaginal dryness and mucosal discoloration in postmenopausal women. In the cited study, the mean severity of dryness and discoloration decreased in the intervention group after the intervention. Unlike the present study, Rad et al. investigated only the state of parabasal cells; yet, their results showed a significant reduction in the mean parabasal cells of the vaginal mucosa in the intervention group compared with those in the controls, which is consistent with the present findings [24].

The present findings concur with the results obtained in a study conducted in Iran by Ziaghami et al. to assess the effect of vaginal suppositories of 1 mg of vitamin E for 8 weeks on vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women. In the cited study, the effect of vitamin E suppositories was assessed exclusively by objective criteria such as pH measurement and changes in the vaginal maturation value (VMV) of the mucosal cells, and no subjective criteria such as self-assessment tools were used; nevertheless, the results showed an increase in the VMV and a significant reduction in the vaginal pH in the intervention group compared with those in the controls [26].

The results of another study conducted in Iran by Ziaghami et al. to compare the effects of the daily use of hyaluronic acid and 1-mg vitamin E vaginal suppositories in the treatment of the symptoms of vaginal atrophy (burning, itching, dryness, and dyspareunia) in postmenopausal women were also consistent with the present findings. The cited study showed a significant reduction in vaginal atrophy symptoms in both groups after the intervention compared with baseline. Although the scales used for measuring vaginal atrophy symptoms, the cause of atrophy and even the type of intervention given were different from the present study, the improvement in symptoms of the vaginal atrophy self-assessment showed that using vitamin E vaginal suppository can improve the subjective symptoms of vaginal atrophy [32].

A clinical trial was conducted in Iran by Golmakani et al. to compare the efficacy of 100 IU of vitamin E vaginal suppository and 0.625 mg of conjugated estrogen vaginal cream on quality of life in postmenopausal women in vasomotor, psychological, physical, and sexual domains. By the end of the intervention, the score of the menopause quality of life instrument increased significantly to suggest an improvement in symptoms. Regardless of the different atrophy symptom assessment tools used in the cited studies, their results also suggest an improvement in these symptoms due to the use of vitamin E vaginal suppositories [33].

In a study conducted by Morali et al., 1-month use of a medical product in the form of a 2.5-g vaginal gel of hyaluronic acid, liposome, and phytoestrogen from Humulus lupulus extract and vitamin E in postmenopausal women with vaginal atrophy reduced dyspareunia significantly. In the cited study, other symptoms of vaginal atrophy also improved, including itching, burning, inflammation, edema, and redness, and an increase was observed in the VMI, which supports the present findings [34].

The study conducted by Costantino et al. to investigate 1-month use of a vaginal suppository of hyaluronic acid, vitamin A, and vitamin E on vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women also showed an improvement in vaginal atrophy symptoms such as itching, burning, and dyspareunia [16]. Dinicola et al. investigated the vaginal smear of women with cervical cancer and vaginal atrophy undergoing radiotherapy, and by the end of month four of the daily use of two suppositories (vitamin A, vitamin E, and hyaluronic acid), the intervention group showed significant improvements in terms of inflammation, cell deformity, fibrosis, mucus inflammation, and bleeding. This intervention was also effective in reducing the complications of radiotherapy and brachytherapy and the severity of pain and improving the symptoms of vaginal atrophy. Although the individual effect of vitamin E on the vaginal mucus was not investigated in the cited studies, using combination products containing vitamin E appears to have also improved the symptoms of vaginal atrophy [35].

The limitations of the present study include the failure to assess the effect of using vitamin E and D suppositories for periods longer than 2 months due to the lack of enough funds for preparing these vaginal suppositories; nevertheless, attempts were made to assess the effect of using these suppositories in this rather short period through objective criteria such as pH and VMI measurement and subjective criteria such as genitourinary symptoms through a vaginal atrophy self-assessment tool for women with breast cancer. In the next steps, we consider to design randomized trials to clarify the result of the current study better. Our research team wants to design these studies with different duration times of intervention, doses of vitamin E and D vaginal suppositories, and pattern of the suppositories used. Additionally, we think to plan a study to compare the effect of vitamin E, vitamin D, and the combination of vitamin D and E vaginal suppositories on tamoxifen-induced vaginal atrophy and its effect on sexual function in women with breast cancer.

Conclusion

The results supported that vitamin D and E vaginal suppositories are beneficial in reducing vaginal pH, improving the VMI and improving the genitourinary symptoms of vaginal atrophy in women with breast cancer receiving tamoxifen. Given the prohibition on hormone therapy in this group of women, these vaginal suppositories can be used to improve the symptoms.

References

Berek JS (2012) Berek and Novak’s gynecology. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia

Enayatrad M, Amoori N, Salehiniya H (2015) Epidemiology and trends in breast cancer mortality in Iran. Iran J Public Health 44(3):430–431

Del Mastro L, Boni L, Michelotti A et al (2011) Effect of the gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogue triptorelin on the occurrence of chemotherapy-induced early menopause in premenopausal women with breast cancer: a randomized trial. JAMA 306(3):269–276. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2011.991

Costa M, Saldanha P (2017) Risk reduction strategies in breast cancer prevention. Eur J Breast Health 13(3):103–112. https://doi.org/10.5152/ejbh.2017.3583

Kim NN, Stankovic M, Armagan A, Cushman TT, Goldstein I, Traish AM (2006) Effects of tamoxifen on vaginal blood flow and epithelial morphology in the rat. BMC Womens Health 6:14

Weber MA, Limpens J, Roovers JPWR (2015) Assessment of vaginal atrophy: a review. Int Urogynecol J 26(1):15–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-017-3490-5

Portman DJ, Bachmann GA, Simon JA, Group OS (2013) Ospemifene, a novel selective estrogen receptor modulator for treating dyspareunia associated with postmenopausal vulvar and vaginal atrophy. Menopause 20(6):623–630. https://doi.org/10.1097/gme.0b013e318279ba64

Simin J, Tamimi R, Lagergren J, Adami HO, Brusselaers N (2017) Menopausal hormone therapy and cancer risk: an overestimated risk? Eur J Cancer 84:60–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2017.07.012

Trabert B, Wentzensen N, Yang HP, Sherman ME, Hollenbeck AR, Park Y, Brinton LA (2013) Is estrogen plus progestin menopausal hormone therapy safe with respect to endometrial cancer risk? Int J Cancer 132(2):417–426. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.27623

Brown SB, Hankinson SE (2015) Endogenous estrogens and the risk of breast, endometrial, and ovarian cancers. Steroids 99:8–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.steroids.2014.12.013

Bergendal A, Kieler H, Sundström A, Hirschberg AL, Kocoska-Maras L (2016) Risk of venous thromboembolism associated with local and systemic use of hormone therapy in peri- and postmenopausal women and in relation to type and route of administration. Menopause 23(6):593–599. https://doi.org/10.1097/GME.0000000000000611

Sousa MS, Peate M, Jarvis S, Hickey M, Friedlander M (2017) A clinical guide to the management of genitourinary symptoms in breast cancer survivors on endocrine therapy. Ther Adv Med Oncol 9(4):269–285. https://doi.org/10.1177/1758834016687260

Lester J, Pahouja G, Andersen B, Lustberg M (2015) Atrophic vaginitis in breast cancer survivors: a difficult survivorship issue. J Pers Med 5(2):50–66. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm5020050

Faubion SS, Larkin LC, Stuenkel CA, Bachmann GA, Chism LA, Kagan R, Kaunitz AM, Krychman ML, Parish SJ, Partridge AH, Pinkerton JAV, Rowen TS, Shapiro M, Simon JA, Goldfarb SB, Kingsberg SA (2018) Management of genitourinary syndrome of menopause in women with or at high risk for breast cancer: consensus recommendations from The North American Menopause Society and The International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health. Menopause 25(6):596–608. https://doi.org/10.1097/GME.0000000000001121

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Gynecologic Practice, Farrell R (2016) ACOG Committee Opinion No. 659 Summary: the use of vaginal estrogen in women with a history of estrogen-dependent breast cancer. Obstet Gynecol 127(3):618–619. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000001349

Costantino D, Guaraldi C (2008) Effectiveness and safety of vaginal suppositories for the treatment of the vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women: an open, non-controlled clinical trial. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 12(6):411–416

Lee YK, Chung HH, Kim JW, Park NH, Song YS, Kang SB (2011) Vaginal pH-balanced gel for the control of atrophic vaginitis among breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 117(4):922–927. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182118790

Wurz GT, Soe LH, DeGregorio MW (2013) Ospemifene, vulvovaginal atrophy, and breast cancer. Maturitas 74(3):220–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2012.12.002

Carter J, Goldfrank D, Schover LR (2011) Simple strategies for vaginal health promotion in cancer survivors. J Sex Med 8(2):549–559. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01988.x

Derzko C, Elliott S, Lam W (2007) Management of sexual dysfunction in postmenopausal breast cancer patients taking adjuvant aromatase inhibitor therapy. Curr Oncol 14(Suppl 1):S20–S40

Juraskova I, Jarvis S, Mok K, Peate M, Meiser B, Cheah BC, Mireskandari S, Friedlander M (2013) The acceptability, feasibility, and efficacy (phase I/II study) of the OVERcome (Olive Oil, Vaginal Exercise, and MoisturizeR) intervention to improve dyspareunia and alleviate sexual problems in women with breast cancer. J Sex Med 10(10):2549–2558. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsm.12156

Mazzarello S, Hutton B, Ibrahim MF et al (2015) Management of urogenital atrophy in breast cancer patients: a systematic review of available evidence from randomized trials. Breast Cancer Res Treat 152(1):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-015-3434-z

Yildirim B, Kaleli B, Düzcan E, Topuz O (2004) The effects of postmenopausal vitamin D treatment on vaginal atrophy. Maturitas 49(4):334–337

Rad P, Tadayon M, Abbaspour M, Latifi SM, Rashidi I, Delaviz H The effect of vitamin D on vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res 20(2):211–215

Lee A, Lee MR, Lee HH et al (2017) Vitamin D proliferates vaginal epithelium through RhoA expression in postmenopausal atrophic vagina tissue. Mol Cell 40(9):677–684

Ziagham S, Abbaspoor Z, Safyari S, Rad P (2013) Effect of vitamin E vaginal suppository on atrophic vaginitis among postmenopausal women. Jundishapur J Chronic Dis Care 2(4):12–19

Abban G, Yildirim NB, Jetten AM (2008) Regulation of the vitamin D receptor and cornifin beta expression in vaginal epithelium of the rats through vitamin D3. Eur J Histochem 52:107–104

Zeyneloglu HB, Oktem M, Haberal NA, Esinler I, Kuscu E (2007) The effect of raloxifene in association with vitamin D on vaginal maturation index and urogenital symptoms in postmenopausal osteoporotic women. Fertil Steril 88(2):530–532

Chollet JA, Carter G, Meyn LA, Mermelstein F, Balk JL (2009) Efficacy and safety of vaginal estriol and progesterone in postmenopausal women with atrophic vaginitis. Menopause 16(5):978–983. https://doi.org/10.1097/gme.0b013e3181a06c80

Speroff L (2003) Efficacy and tolerability of a novel estradiol vaginal ring for relief of menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol 102(4):823–834

Lester J, Bernhard L, Ryan-Wenger N (2012) A self-report instrument that describes urogenital atrophy symptoms in breast cancer survivors. West J Nurs Res 34(1):72–96. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193945910391483

Ziagham Z, Abbaspoor Z, Abbaspour MR (2012) The comparison between the effects of hyaluronic acid vaginal suppository and vitamin e on the treatment of atrophic vaginitis in menopausal women. J Arak Uni Med Sci 15(6):57–64

Emamverdikhan AZ, Golmakani N, SharifiSistani N, Shakeri MT, Hasanzade Mofrad M, Sajadi Tabassi A (2014) Comparing two treatment methods of vitamin E suppository and conjugated estrogen vaginal cream on the quality of life in menopausal women with vaginal atrophy. J Midwif Reprod Health 2(4):253–261. https://doi.org/10.22038/JMRH.2014.3246

Morali G, Polatti F, Metelitsa EN, Mascarucci P, Magnani P, Marrè GB (2006) Open, non-controlled clinical studies to assess the efficacy and safety of a medical device in form of gel topically and intravaginally used in postmenopausal women with genital atrophy. Arzneimittelforschung 56(3):230–238

Dinicola S, Pasta V, Costantino D, Guaraldi C, Bizzarri M (2015) Hyaluronic acid and vitamins are effective in reducing vaginal atrophy in women receiving radiotherapy. Minerva Ginecol 67(6):523–531

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The research project was approved by the ethics committee of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences (IR.SUMS.REC 94-01-08-11247) and registered at the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT2016100229683N2).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Keshavarzi, Z., Janghorban, R., Alipour, S. et al. The effect of vitamin D and E vaginal suppositories on tamoxifen-induced vaginal atrophy in women with breast cancer. Support Care Cancer 27, 1325–1334 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-04684-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-04684-6