Abstract

Purpose

To compare patients’ evaluation of the treatment decision-making process in localized prostate cancer between counseling that included an online decision aid (DA) and standard counseling.

Methods

Eighteen Dutch hospitals were randomized to DA counseling (n = 235) or the control group with standard counseling (n = 101) in a pragmatic, cluster randomized controlled trial. The DA was provided to patients at, or soon after diagnosis. Decisional conflict, involvement, knowledge, and satisfaction with information were assessed with a questionnaire after treatment decision-making. Anxiety and depression served as covariates.

Results

The levels of decision involvement and conflict were comparable between patients in both groups. Patients with a DA felt more knowledgeable but scored equally well on a knowledge test as patients without a DA. Small significant negative effects were found on satisfaction with information and preparation for decision-making. A preference for print over online and depression and anxiety symptoms was negatively associated with satisfaction and conflict scores in the DA group.

Discussion

The DA aimed to support shared decision-making, while outcomes for a majority of DA users were comparable to patients who received standard counseling. Patients, who are less comfortable with the online DA format or experience anxiety or depression symptoms, could require more guidance toward shared decision-making. To evaluate long-term DA effects, follow-up evaluation on treatment satisfaction and decisional regret will be done.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

In a clinical area where multiple equal effective treatments are available for the same medical condition, the preference-sensitive treatment selection that is then required can be challenging for patients as well as physicians [1,2,3]. Treatment selection for localized prostate cancer (Pca), the most commonly detected cancer in men in the Western world, is such an area [4]. When diagnosed at a localized stage, Pca can be managed with equal successful curative treatments (surgery or radiotherapy), or by following an active surveillance (AS) protocol without harming survival perspectives [5,6,7,8]. Although oncologically equivalent, treatments differ in their impact on quality of life, risk of side effects, and perceived burden; therefore, Pca treatment guidelines do not indicate a single superior treatment option, but recommend shared decision-making (SDM) to come to the best patient-treatment fit [5, 6, 9,10,11]. Moreover, many Pca patients have a poor understanding of differences in treatment risks prior to choosing treatment, are dissatisfied with information received, and experience regret after treatment [12,13,14]. With SDM and more decision support, these problems can be resolved.

SDM requires patients to share preferences, uncertainties, and the desired level of participation in the decision process. A physician should be aware of the patient’s preferred level of involvement and take this into account to adequately provide all available information about eligible options, including risks, benefits, and scientific uncertainties [15, 16]. However, patient preferences for involvement are often misinterpreted by care providers and many patients are dissatisfied with the information they received [17,18,19,20].

To facilitate and improve the process of SDM, patient decision aids (DAs) were developed to help patients to increase choice awareness, provide high quality information, structure the decision process, and to help clarify preferences and values [21,22,23]. Simple DAs are plain paper versions, while more elaborate DAs are built as interactive websites that include explicit values clarification methods [24, 25]. DA effects are typically studied by comparing patient-reported outcomes following decision-making between a DA group and a usual care group. In a review of DAs across all medical screening and treatment decisions, it has been shown that DAs contribute to improved patient involvement in the treatment decision, less decisional conflict, and more conservative treatment choices [26].

In the specific area of Pca treatment decision-making, DA results are less conclusive. Positive effects are seen for improved patient education (knowledge, information satisfaction), but mixed effects are found for other decision process measures, such as decisional conflict [27]. Often the studied Pca DAs did not fully comply with the International Patient Decision Aid Standards (IPDAS), mostly because of missing DA development information or unbalanced presentation of treatment benefits and risk. Furthermore, they lacked a user-centered design or were not specifically aimed at facilitating SDM in the patient-doctor encounter [23, 27,28,29].

In the absence of a Dutch Pca treatment DA that included a values clarification method, a novel web-based DA was developed with a specific user-centered focus on facilitating SDM [30]. A cluster randomized controlled trial (RCT) that compared DA counseling to a control arm with standard counseling was set up. The primary finding, that the DA helped patients align treatment choices to their personal preferences, was published previously [31]. The current study investigated patient-reported outcomes related to the decision-making process, directly following treatment decision-making. We hypothesized that with the DA decisional conflict (primary outcome) would be lower and patient involvement, Pca knowledge and information satisfaction (secondary outcomes) would be better, compared to the control group [18]. Moreover, we were interested in individual differences (DA format preference, anxiety, and depression symptoms) among DA users to explain potential differences in outcomes within the trial’s DA arm.

Methods

Participants and recruitment

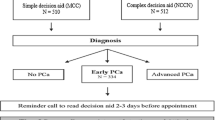

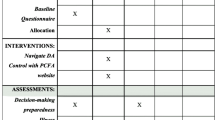

All patients from participating hospitals, who were newly diagnosed with localized Pca (PSA < 20, Gleason < 8) between August 1, 2014 and July 1, 2016, had at least two treatment options and no mental or cognitive impairments, were suitable for enrollment in this trial. Patients were recruited at diagnosis, by their urologist or by an (oncology) nurse, immediately following diagnosis, and were given a study package containing an information letter, informed consent form, leaflet, and a pre-stamped envelope. To agree with participation, the informed consent form had to be returned using the pre-stamped envelope. On the informed consent form, patients indicated the date of their next consultation, which usually was 2 or 3 weeks following diagnosis and the moment to discuss treatment choice. A questionnaire was sent within 1 week after this indicated date by email (paper version on request) [18].

Design

Eighteen Dutch hospitals were randomized to the intervention or control arm. All hospitals were general hospitals, except for one academic hospital in the control arm. Patients in the control arm received information and counseling as usual, patients from hospitals in the intervention arm received access to the online DA in addition to usual information and counseling. Randomization at hospital level was chosen to avoid contamination of usual counseling with components of the DA. Patients were informed that the topic of the study was to evaluate information provision and treatment decision-making in Pca care, and were unaware of assignment to trial arm as the DA was not mentioned as subject of this study. The regional Medical Ethics Review Board waived the need for formal ethical approval (reference: NW2014-03), and the study protocol was approved by every individual hospital. The study was pre-registered in the Dutch Trial Register (NTR4554).

Intervention

To invite patients to use the DA, patients in the intervention arm received an access card from their health care provider with the DA-web address and a unique username and password. The card also stated the patient’s relevant clinical characteristics, that is, eligible treatment options (AS, surgery, brachytherapy, or external radiation), PSA, and Gleason score. Based on the indicated treatment options, the DA allowed patients to skip information about non-eligible treatments. After accessing the DA and entering the clinical data from the card, patients first could read general information about Pca, before detailed information about AS and treatments was provided. Provided treatment information within the DA was similar for each treatment and consisted of information about procedures, risks, and pros and cons. Information was based on (inter)national guidelines and recent scientific literature. Values clarification methods (VCMs) were included to help patients clarify their personal preference for AS or any of the treatments. VCMs were designed as statements that required a trade-off between two treatment modalities (e.g. “If treatment might be unnecessary, I prefer to wait,” as trade-off between AS and treatment). The DA ended with a summary page that displayed how extensive the DA was used (e.g. “You have read x out of x topics”), the patient’s responses to the VCMs and indicated treatment preference. A printed summary could be taken to the subsequent consultation where the treatment decision was discussed with the urologist. The goal of the summary page is to enable a SDM conversation as it presents the patient’s preferences on the various VCMs and for treatment. A more detailed description of the development and content of this novel Dutch web-based DA is available in a separate publication, which also provides evidence for IPDAS compliance of the current DA [28, 30].

Procedures

In addition to usual information, patients in the intervention arm were granted access to the online DA. The pragmatic aspect of the current trial allowed hospitals to follow their existing procedures and routines for further counseling. For some hospitals, this meant that all newly diagnosed patients saw a radiation oncologist (when eligible for radiotherapy) and an oncology nurse, while at other hospitals this only happened by patient request. Most patients took 2 or 3 weeks to consider their treatment choice before a follow-up consultation was scheduled. Patients in the intervention arm received explanation that the DA should be used during this period, and that the summary provided by the DA, could be taken to the next consultation, although this was not mandatory. In the week following the treatment decision, patients in both arms were invited to fill out the questionnaire online or a paper questionnaire was sent on request. Automatic reminders were sent after 2 and 4 weeks if the questionnaire had not yet been started or completed.

Measures

Sociodemographic and clinical information was obtained from informed consent (date of diagnosis, date of birth) and the questionnaire (marital status, education level, treatment options, treatment choice, and self-administered co-morbidities). Eligible treatments and the received treatment were verified through the patient’s medical record; this data was also used for a separate analysis of treatment choices within this trial [31]. Individual differences between patients in general anxiety and depression symptoms were assessed with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [32].

Main outcome of this study was decisional conflict, which was measured with the Dutch version of Decisional Conflict Scale (DCS), incorporating five subscales regarding feeling uninformed, values clarity, perceived support, decision uncertainty, and the perceived effectiveness of the decision. Scales were converted to 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating more perceived conflict [33, 34]. Internal consistency of the full scale was good (Cronbachs alpha, 0.87, subscales 0.58–0.86). Secondary outcomes included two single items on the patient’s perceived role during decision-making (Problem-Solving Decision-Making Scale) and the perceived preparedness to make the treatment decision (Preparation for Decision-making Scale, alpha = 0.97) [35, 36]. Pca knowledge was assessed with an estimation of the perceived knowledge level per treatment (e.g. “How well do you think your knowledge about surgery is?”) and an objective test consisting of five multiple-choice test questions from the Pca Decision Quality Instrument [37]. Additionally, satisfaction with timing and format of the information received was measured with the corresponding subscale of the Satisfaction with Cancer Information Profile (SCIP-B, alpha = 0.96) [38]. In the DA arm, participants received additional questions to evaluate the DA (e.g. “Was the online DA format your preferred format?” and “Would you preferred if the DA had provided you with a treatment advice?”).

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics are presented as means (+/− SD) for continuous variables and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. Differences between study arms and between responders and non-responders were tested using independent sample t tests for continuous variables and chi-square analyses for categorical variables.

Analyses were performed according to the intention-to-treat principle, assuming that counseling in the DA group was different from the control group because of the introduction of the DA, regardless of actual DA usage by participants. To take the hierarchical structure of the data—due to randomization at hospital level—into account and control for hospital specific effects, linear multilevel regression analyses were used to test the effect of the intervention (the DA) compared to the control group. Study arm (DA vs. usual care) was included in the model as an independent variable. Dependent variables consisted of decisional conflict, involvement, knowledge, and information satisfaction. Participants’ HADS scores served as covariate as anxiety and depression symptoms are common after receiving a cancer diagnosis and are known to be related to the evaluation of information provision [39, 40]. Subgroup analyses were performed on participants from which DA log data indicated the DA was actually used. Participants were grouped according to their DA format preference (online versus paper) and HADS score. HADS scores were initially categorized into normal (0–7), mild [8,9,10], moderate [11,12,13,14], and severe (≥ 15), according to previous studies [41]. Because differences between the mild and moderate group are of little clinical relevance, and to ensure higher statistical power, the mild and moderate categories were collapsed into one group.

The study was powered to detect a clinically relevant effect size of 0.50 between both study arms on decisional conflict. A conservative intra-class coefficient (ICC) of 0.01 was taken; therefore, to obtain 80% power and allow for 25% attrition in the current questionnaire and follow-ups, 238 patients per study arm were targeted [18]. Eventually, fewer patients than targeted were recruited for the control group (n = 109). Due to the conservative sample size calculation, power for making comparisons between arms was still sufficient (> 0.80), but low for comparing smaller subgroups (0.65–0.67). Statistical analyses were conducted using the SPSS 22.0 (Statistical Package for Social Sciences, Chicago, IL). Tests were two-sided and considered statistically significant if p < 0.05.

Results

Based on national cancer registry data, the estimated total number of eligible patients during the trial period was 2000 patients, of which 484 patients were invited to participate in the trial. A total of 382 Pca patients signed informed consent (DA = 273 and control = 109, consent rate 79%), and 336 patients filled out the post-decision questionnaire (response rate 88%). The mean age of responders was 65.3 (SD = 5.9), there were no differences in sociodemographic or clinical characteristics in participants between both study arms (Table 1). Questionnaire non-responders were younger than responders (M = 62.9 vs. M = 65.3, p = 0.01), although the distribution among age groups was comparable (p = 0.18; Table 2). Furthermore, non-responders were less likely to have accessed the DA compared to responders (68 vs. 86%, p = 0.005). The number of patients enrolled per hospital varied between 1 and 64 (Table 1), response rates from all hospitals except one were higher than 80% (Table 2).

Between trial arms, no differences were found on involvement or decisional conflict (Table 3). Participants in the DA arm felt more knowledgeable, but less prepared to make a decision (Table 3). Overall information satisfaction was lower in the DA arm, in particular for information usability, the amount of information, and completeness of the information (Table 3). The mean objective knowledge (test) scores were comparable between trial arms (Table 3); however, within the control arm, knowledge scores were lower for patients eligible for 3 or 4 treatments (F(2, 84) = 5.84, p = 0.004), while in the DA arm, test scores were unrelated to the number of eligible treatments.

A subgroup analysis revealed that 84% of actual DA users (N = 156) were in favor of the online DA format and 16% (N = 30) would preferred to have received the DA in print. Of participants who received but did not access the DA, 56% (N = 15) indicated a DA in print was preferred. Participants favoring the online DA format were younger (M = 64.6 vs. M = 67.3, p = 0.02) and more often highly educated (50% highly educated vs. 27%, p = 0.04). Mean HADS scores were not statistically significantly different between both format preference groups, however, medium or severe HADS scores were more common in participants who would prefer a printed DA (p = 0.03). DA users in favor of the online DA format and with HADS scores < 8 reported less decisional conflict and more information satisfaction compared to other DA users (Table 4). A treatment advice from the DA was preferred more often by DA users with severe of high HADS scores, although differences did not reach statistical significance (Table 4). No other sociodemographic variables were associated to differences between DA users. The same HADS categorization did not yield statistically significant differences in the control arm (data not shown).

Discussion

In this pragmatic cluster randomized controlled trial among patients with localized Pca, adding an online DA to standard counseling did not lead to different levels of patient involvement or decisional conflict in comparison to standard counseling. Patients who used the DA did feel more knowledgeable about Pca treatments but scored equally well as participants from the control group on a knowledge test. Small negative effects of the DA were found on the scales for preparation for decision-making and information satisfaction, in particular for DA users with medium or high anxiety and depression symptoms or who would preferred the DA to be in print.

With the DA, patients were provided with structured information about Pca and possible treatments. Treatment advantages and disadvantages were presented in a balanced manner, and VCMs were included to help patients establish a treatment preference based on personal values [30]. An earlier investigation into treatment choices within this trial revealed that with the current DA, the treatment decisions were more often in line with the patient’s preference instead of the doctor’s preference [31]. However, this did not translate into an effect on decisional conflict in the current study, with previous Pca DA studies also finding mixed results on this outcome [27] . Possibly, this is because of the nature of the concept of decisional conflict. Despite the wide use of decisional conflict as an outcome measure in DA evaluations, it has been debated whether lowering decisional conflict should actually be the desired outcome of a DA intervention [26, 27, 42, 43]. Careful consideration of all available treatment options, including weighing pros and cons against personal preferences, could evoke conflict and the perceived decision difficulty, regardless of interventions to support the decision-making process. If ultimately, the final decision has a better patient-treatment fit, existence or even increase of decisional conflict could also be the expense of a thorough decision-making process [44, 45]. Follow-up evaluation of our trial participants is planned to determine if patients are more satisfied with the selected treatment and experience less regret, after treatment is completed, compared to patients from the control group.

Next to finding no effect on decisional conflict, the effects from the DA on the secondary outcomes, preparation for decision-making and information satisfaction, were small but opposite from what was expected and overall findings in DA studies [18, 26]. Although patients were unaware of randomization at hospital level and were not informed that the DA was the subject of this study, care providers were aware that the purpose of the study was to compare the DA to usual information routines. During counseling, the novelty of the DA might have been over-emphasized, increasing patients’ expectations and leading to a more critical evaluation of the DA in the questionnaire. An indication that some participants might have had other expectations from the DA was found in the proportion of patients who indicated they would like to have received an explicit treatment advice from the DA, while this was not provided by the DA.

Some evidence for an effect of the DA on knowledge was found. Firstly, participants with a DA perceived themselves to be more knowledgeable. Secondly, participants in the DA group scored equally well on the knowledge test, regardless of the number of eligible treatments, while in the control group test scores were lower if the number of eligible treatment options increased. This could indicate that when more treatments are considered, the DA helps to gain more knowledge about all options resulting in a better informed treatment decision, while in the control group there might have been more focus on a single treatment [42].

Not all participants seemed equally suited to receive the DA in its current online format. Older and lower educated participants indicated more often that a print DA was preferred over the current online format. Internet access is common in the Netherlands, also among elderly, of all people aged up to 75 years, 97% has internet access at home (statline.cbs.nl). However, with increasing age, actual usage and comfort in using internet is lower, which could explain some hesitation among participants to engage in an online tool for making a high impact treatment decision [46]. Participants with anxiety and depression symptoms showed more decisional conflict and less information satisfaction with the DA compared to participants with similar symptoms from the control condition. Anxiety and depression is common after a cancer diagnosis [39]. However, for participants in the control condition, we did not find a moderating role of anxiety and depression symptoms on decisional conflict or information satisfaction. This could indicate that without a DA, care providers were able to tailor their counseling according to the estimated level of anxiety and depression, while with the DA, all information about risks and side effects was presented equally explicit to all patients. Communicating uncertainty can lead to lower satisfaction, in particular if patients are more sensible to this because of anxiety or depression [44]. Further research is needed to determine if these groups require further tailored information provision or more guidance in using a DA.

The role of the DA in tailored information should be investigated in future research. During the current trial, most men received the DA soon after diagnosis, and were instructed to use the DA after consultation, regardless of any psychosocial distress from receiving the Pca diagnosis. Distress could have hindered uptake of new information from the DA and the decision-making process [47]. Possibly, some patients benefit from more extensive nurse counseling throughout the decision process and emotions caused by the diagnosis before the DA is introduced. Detailed analysis (by audio or video) of clinical consultations could be helpful to investigate to what extent psychosocial distress plays a role during treatment counseling, and if the DA is of more added value with a tailored approach with various levels of nurse guidance [48].

A major strength of this study was the cluster randomized design to reduce the risk of contamination of standard counseling with components of the DA. Consequently, care providers in the DA arm were able to develop a routine in distributing and explaining the DA. Furthermore, many patients were recruited in the DA arm and once distributed, many patients used the DA.

Some limitations need to be mentioned as well. Firstly, recruitment of participants in the control arm was slower and resulted in less participants than aimed for. Although patient characteristics were very similar in both arms, we cannot exclude a potential selection bias in the control arm which may have led to recruiting only patients who were more likely to consent. Secondly, as mentioned before, care providers were aware of randomization and the true focus of this study. In the control arm, this could have led to modifications of existing information or counseling routines due to the increased attention for SDM from this study, or in the DA group, to the creating of too high expectations as care providers could have (over-)emphasized the novelty of the DA. Thirdly, although the DA achieved a high usage rate, non-users were more likely to also not respond to the questionnaire. The evaluation of patient who chose not to use the DA are therefore underrepresented in the current sample. A qualitative study could provide more insights in their motives to not use the DA.

This study measured DA effects immediately following treatment decision-making. Previous research showed that effects from VCMs included in DAs could also emerge at a later point than at treatment decision-making [49]. Post-treatment follow-ups in the current sample on treatment satisfaction and decisional regret are needed to determine if this is also the case for this DA [18].

In conclusion, this study did not find evidence of beneficial effects from the DA on patient-reported decision process parameters. Importantly, patients who do not favor the online DA format or present with anxiety and depression symptoms could require more guidance and support during DA use and treatment counseling. The effect of the DA on treatment satisfaction and decisional regret once treatment is completed, needs to be investigated in a follow-up study.

References

Chen RC, Basak R, Meyer A et al (2017) Association between choice of radical prostatectomy, external beam radiotherapy, brachytherapy, or active surveillance and patient-reported quality of life among men with localized prostate cancer. JAMA 317(11):1141–1150

Holmes-Rovner M, Montgomery JS, Rovner DR, Scherer LD, Whitfield J, Kahn VC, Merkle EC, Ubel PA, Fagerlin A (2015) Informed decision making: assessment of the quality of physician communication about prostate cancer diagnosis and treatment. Med Decis Mak 35(8):999–1009

Pieterse AH, Henselmans I, de Haes HCJM, Koning CCE, Geijsen ED, Smets EMA (2011) Shared decision making: prostate cancer patients’ appraisal of treatment alternatives and oncologists’ eliciting and responding behavior, an explorative study. Patient Educ Couns 85(3):e251–e2e9

Ferlay J, Steliarova-Foucher E, Lortet-Tieulent J, Rosso S, Coebergh JWW, Comber H, Forman D, Bray F (2013) Cancer incidence and mortality patterns in Europe: estimates for 40 countries in 2012. Eur J Cancer 49(6):1374–1403

Carter HB, Albertsen PC, Barry MJ, Etzioni R, Freedland SJ, Greene KL, Holmberg L, Kantoff P, Konety BR, Murad MH, Penson DF, Zietman AL (2013) Early detection of prostate cancer: AUA Guideline. J Urol 190(2):419–426

Heidenreich A, Bastian PJ, Bellmunt J, Bolla M, Joniau S, van der Kwast T, Mason M, Matveev V, Wiegel T, Zattoni F, Mottet N, European Association of Urology (2014) EAU guidelines on prostate cancer. Part 1: screening, diagnosis, and local treatment with curative intent—update 2013. Eur Urol 65(1):124–137

Cooperberg MR, Carroll PR, Klotz L (2011) Active surveillance for prostate cancer: progress and promise. J Clin Oncol 29(27):3669–3676

DeSantis CE, Lin CC, Mariotto AB, Siegel RL, Stein KD, Kramer JL, Alteri R, Robbins AS, Jemal A (2014) Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin 64(4):252–271

Resnick MJ, Koyama T, Fan K-H, Albertsen PC, Goodman M, Hamilton AS, Hoffman RM, Potosky AL, Stanford JL, Stroup AM, van Horn RL, Penson DF (2013) Long-term functional outcomes after treatment for localized prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 368(5):436–445

van Tol-Geerdink JJ, Leer JWH, van Oort IM, van Lin EJNT, Weijerman PC, Vergunst H, Witjes JA, Stalmeier PFM (2013) Quality of life after prostate cancer treatments in patients comparable at baseline. Br J Cancer 108(9):1784–1789

Bellardita L, Valdagni R, van den Bergh R, Randsdorp H, Repetto C, Venderbos LDF, Lane JA, Korfage IJ (2015) How does active surveillance for prostate cancer affect quality of life? A systematic review. Eur Urol 67(4):637–645

van Stam M-A, van der Poel HG, van der Voort van Zyp JRN, Tillier CN, Horenblas S, Aaronson NK et al The accuracy of patients’ perceptions of the risks associated with localised prostate cancer treatments. BJU Int 121(3):405–414

Christie DRH, Sharpley CF, Bitsika V (2015) Why do patients regret their prostate cancer treatment? A systematic review of regret after treatment for localized prostate cancer. Psycho-Oncology 24(9):1002–1011

Lamers RED, Cuypers M, Husson O, de Vries M, Kil PJM, Ruud Bosch JLH, van de Poll-Franse LV (2016) Patients are dissatisfied with information provision: perceived information provision and quality of life in prostate cancer patients. Psycho-Oncology 25(6):633–640

Stiggelbout AM, Pieterse AH, De Haes JCJM (2015) Shared decision making: concepts, evidence, and practice. Patient Educ Couns 98(10):1172–1179

Kunneman M, Montori VM, Castaneda-Guarderas A, Hess EP (2016) What is shared decision making? (and what it is not). Acad Emerg Med 23(12):1320–1324

Couët N, Desroches S, Robitaille H, Vaillancourt H, Leblanc A, Turcotte S, Elwyn G, Légaré F (2015) Assessments of the extent to which health-care providers involve patients in decision making: a systematic review of studies using the OPTION instrument. Health Expect 18(4):542–561

Cuypers M, Lamers RED, Kil PJM, van de Poll-Franse LV, de Vries M (2015) Impact of a web-based treatment decision aid for early-stage prostate cancer on shared decision-making and health outcomes: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 16(1):1–10

Mulley AG, Trimble C, Elwyn G (2012) Stop the silent misdiagnosis: patients’ preferences matter. BMJ : Br Med J 345:e6572

Street RL, Haidet P (2011) How well do doctors know their patients? Factors affecting physician understanding of patients’ health beliefs. J Gen Intern Med 26(1):21–27

Thompson R, Trevena L (2016) Demystifying decision aids: a practical guide for clinicians. In: Shared decision making in health care: achieving evidence-based patient choice, 3rd edn. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Elwyn G, Frosch D, Thomson R, Joseph-Williams N, Lloyd A, Kinnersley P, Cording E, Tomson D, Dodd C, Rollnick S, Edwards A, Barry M (2012) Shared decision making: a model for clinical practice. J Gen Intern Med 27(10):1361–1367

Elwyn G, O'Connor A, Stacey D, Volk R, Edwards A, Coulter A, Thomson R, Barratt A, Barry M, Bernstein S, Butow P, Clarke A, Entwistle V, Feldman-Stewart D, Holmes-Rovner M, Llewellyn-Thomas H, Moumjid N, Mulley A, Ruland C, Sepucha K, Sykes A, Whelan T, International Patient Decision Aids Standards (IPDAS) Collaboration (2006) Developing a quality criteria framework for patient decision aids: online international Delphi consensus process. BMJ 333(7565):417–410

O’Connor AM, Wennberg JE, Legare F, Llewellyn-Thomas HA, Moulton BW, Sepucha KR et al (2007) Toward the ‘tipping point’: decision aids and informed patient choice. Health Aff 26(3):716–725

Pieterse AH, de Vries M, Kunneman M, Stiggelbout AM, Feldman-Stewart D (2013) Theory-informed design of values clarification methods: a cognitive psychological perspective on patient health-related decision making. Soc Sci Med 77:156–163

Stacey D, Légaré F, Lewis K, Barry MJ, Bennett CL, Eden KB, et al (2017) Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4)

Violette PD, Agoritsas T, Alexander P, Riikonen J, Santti H, Agarwal A, Bhatnagar N, Dahm P, Montori V, Guyatt GH, Tikkinen KA (2015) Decision aids for localized prostate cancer treatment choice: systematic review and meta-analysis. CA Cancer J Clin 65(3):239–251

Elwyn G, O’Connor AM, Bennett C, Newcombe RG, Politi M, Durand MA et al (2009) Assessing the quality of decision support technologies using the International Patient Decision Aid Standards instrument (IPDASi). PLoS One 4:e4705

Adsul P, Wray R, Spradling K, Darwish O, Weaver N, Siddiqui S (2015) Systematic review of decision aids for newly diagnosed patients with prostate cancer making treatment decisions. J Urol 194(5):1247–1252

Cuypers M, Lamers RE, Kil PJ, The R, Karssen K, van de Poll-Franse, LV, et al A global, incremental development method for a web-based prostate cancer treatment decision aid and usability testing in a Dutch clinical setting. Health Informatics J. https://doi.org/10.1177/1460458217720393

Lamers RED, Cuypers M, de Vries M, van de Poll-Franse LV, Ruud Bosch JLH, Kil PJM (2017) How do patients choose between active surveillance, radical prostatectomy, and radiotherapy? The effect of a preference-sensitive decision aid on treatment decision making for localized prostate cancer. Urol Oncol 35(2):37.e9–37e17

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP (1983) The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 67(6):361–370

O'Connor AM (1995) Validation of a decisional conflict scale. Med Decis Mak 15(1):25–30

Koedoot N, Molenaar S, Oosterveld P, Bakker P, de Graeff A, Nooy M, Varekamp I, de Haes H (2001) The decisional conflict scale: further validation in two samples of Dutch oncology patients. Patient Educ Couns 45(3):187–193

Deber RB, Kraetschmer N, Irvine J (1996) What role do patients wish to play in treatment decision making? Arch Intern Med 156(13):1414–1420

Bennett C, Graham ID, Kristjansson E, Kearing SA, Clay KF, O’Connor AM (2010) Validation of a preparation for decision making scale. Patient Educ Couns 78(1):130–133

Sepucha K (2010) Decision Quality Worksheet: For Treating Prostate Cancer v.1.0.: ©Massachusetts General Hospital; last reviewed 2013. Available from: Downloaded from: http://www.massgeneral.org/decisionsciences/research/DQ_Instrument_List.aspx

Llewellyn CD, Horne R, McGurk M, Weinman J (2006) Development and preliminary validation of a new measure to assess satisfaction with information among head and neck cancer patients: the satisfaction with cancer information profile (SCIP). Head Neck 28(6):540–548

Linden W, Vodermaier A, MacKenzie R, Greig D (2012) Anxiety and Depression after cancer diagnosis: prevalence rates by cancer type, gender, and age. J Affect Disord 141(2–3):343–351

Beekers N, Husson O, Mols F, van Eenbergen M, van de Poll-Franse LV (2015) Symptoms of anxiety and depression are associated with satisfaction with information provision and internet use among 3080 cancer survivors: results of the PROFILES registry. Cancer Nurs 38(5):335–342

Anderson J, Burney S, Brooker JE, Ricciardelli LA, Fletcher JM, Satasivam P, Frydenberg M (2014) Anxiety in the management of localised prostate cancer by active surveillance. BJU Int 114:55–61

Orom H, Biddle C, Underwood W III, Nelson CJ, Homish DL (2016) What is a “good” treatment decision? Decisional control, knowledge, treatment decision making, and quality of life in men with clinically localized prostate cancer. Med Decis Mak 36(6):714–725

Vickers AJ (2017) Decisional conflict, regret, and the burden of rational decision making. Med Decis Mak 37(1):3–5

Politi MC, Clark MA, Ombao H, Dizon D, Elwyn G (2011) Communicating uncertainty can lead to less decision satisfaction: a necessary cost of involving patients in shared decision making? Health Expect 14(1):84–91

Elwyn G, Miron-Shatz T (2010) Deliberation before determination: the definition and evaluation of good decision making. Health Expect 13(2):139–147

Deursen AJV, Helsper EJ (2015) A nuanced understanding of Internet use and non-use among the elderly. Eur J Commun 30(2):171–187

O'Callaghan C, Dryden T, Hyatt A, Brooker J, Burney S, Wootten AC, White A, Frydenberg M, Murphy D, Williams S, Schofield P (2014) ‘What is this active surveillance thing?’ Men’s and partners’ reactions to treatment decision making for prostate cancer when active surveillance is the recommended treatment option. Psycho-Oncology 23(12):1391–1398

Budden LM, Hayes BA, Buettner PG (2014) Women’s decision satisfaction and psychological distress following early breast cancer treatment: a treatment decision support role for nurses. Int J Nurs Pract 20(1):8–16

Feldman-Stewart D, Tong C, Siemens R, Alibhai S, Pickles T, Robinson J, Brundage MD (2012) The impact of explicit values clarification exercises in a patient decision aid emerges after the decision is actually made: evidence from a randomized controlled trial. Med Decis Mak 32(4):616–626

Acknowledgements

We thank all patients and staff from the hospitals involved in this study for their contribution. We are grateful to PROFILES for the use of the data collection system, and we would like to thank Nicole Horevoorts in particular for her assistance in data management and collecting questionnaires.

Funding

This research is funded by CZ Fund, a Dutch not-for profit health insurer (Grant 2013-00070) and Delectus Foundation, a Dutch non-profit foundation aimed to initiate and stimulate research into shared decision-making. The funding agreements ensured the authors’ independence in designing, conducting, and analyzing the results. MdV obtained funding from CZ; PK is chairman of Delectus Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no further conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Cuypers, M., Lamers, R.E.D., Kil, P.J.M. et al. Impact of a web-based prostate cancer treatment decision aid on patient-reported decision process parameters: results from the Prostate Cancer Patient Centered Care trial. Support Care Cancer 26, 3739–3748 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-018-4236-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-018-4236-8