Abstract

Background

Participation in camps, adventure programs, retreats, and other social events offers experiences that can promote self-efficacy and quality of life.

Purpose

The purpose of the study was to examine whether participation in a 1-week outdoor adventure program resulted in improvements in psychological distress, self-efficacy, and/or social support for young adult cancer patients (AYAs) aged 18–40 years. The study examined the differential effect of participation for AYAs who indicated moderate to severe symptoms of psychological distress prior to their trip.

Methods

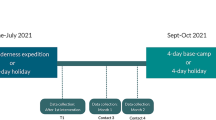

Standardized measures of distress, self-efficacy, and social support were administered pre-trip, post-trip, and 1 month after program completion (follow-up). Univariate and multivariate models examined baseline scores for non-distressed participants compared to distressed participants, changes in outcomes from pre-trip to post-trip and follow-up for the entire sample, and the extent to which change rates for each outcome differed for distressed versus non-distressed participants.

Results

All participants demonstrated significant improvement in self-efficacy over time. Distressed participants reported a significantly greater decrease in distress symptoms and greater increase in self-efficacy and social support at post-trip and 1 month later when compared to non-distressed participants.

Conclusions

Findings suggest that participation in an outdoor recreational activity designed specifically for AYAs with cancer contributes to significant reductions in distress and improvements in self-efficacy and social support, and particularly for AYAs reporting clinically significant distress symptoms prior to the initiation of their activity.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Rowland JH Developmental stage and adaptation: adult model. In J.C. Holland & J.H. Rowland, (Eds.), Handbook of psychooncology, (chapter 3). 1990. New York: Oxford University Press

Warner EL et al (2016) Social well-being among adolescents and young adults with cancer: a systematic review. Cancer 122:1029–1037

D'Agostino N, Penney A, Zebrack B (2011) Providing developmentally appropriate psychosocial care to adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Cancer 117(10 suppl):2329–2334

Zebrack B, Isaacson S (2012) Psychosocial care of adolescent and young adult (AYA) cancer patients and survivors. J Clin Oncol 30(11):1221–1226

Roberts C et al (1997) A support group intervention to facilitate young adults’ adjustment to cancer. Health Soc Work 22(2):133–141

Zebrack B et al (2006) Advocacy skills training for young adult cancer survivors: the Young Adult Survivors Conference (YASC) at Camp Mak-a-Dream. Support Care Cancer 14:779–782

Crom DB (2009) “I think you are pretty: I don’t know why everyone can’t see that”: reflections from a young adult brain tumor survivor camp. J Clin Oncol 27(19):3259–3261

Bandura A (1997) Self-efficacy: the exercise of control. W.H. Freeman and Company, New York

Merluzzi, T.V., et al., Self-efficacy for coping with cancer: revision of the Cancer Behavior Inventory (version 2.0). Psycho-Oncology, 2001. 10: p. 206–217.

Lev EL, Owen SV (2000) Counseling women with breast cancer using principles developed by Albert Bandura. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care 36(4):131–138

Weber BA et al (2007) The impact of dyadic social support on self-efficacy and depression after radical prostatectomy. Journal of Aging and Health 19(4):630–645

Giese-Davis J et al (2006) The effect of peer counseling on quality of life following diagnosis of breast cancer: an observational study. Psycho-Oncology 15:1014–1022

Cunningham A, Lockwood CM, Cunningham JA (1991) A relationship between perceived self-efficacy and quality of life in cancer patients. Patient Educ Couns 17:71–78

Gill E et al (2016) Outdoor adventure therapy to increase physical activity in young adult cancer survivors. J Psychosoc Oncol 34(3):184–199

Elad P et al (2003) A jeep trip with young adult cancer survivors: lessons to be learned. Support Care Cancer 11(4):201–206

Stevens B et al (2004) Adventure therapy for adolescents with cancer. Pediatric Blood Cancer 43:278–284

Berman MG, Jonides J, Kaplan S (2008) The cognitive benefits of interacting with nature. Psychol Sci 19:1207–1212

Cimprich B, Ronis DL (2003) An environmental intervention to restore attention in women with newly diagnosed breast cancer. Cancer Nurs 26(4):284–292

Helgeson VS, Lepore SJ, Eton DT (2006) Moderators of the benefits of psychoeducational interventions for men with prostate cancer. Health Psychol 25:348–354

Torok S et al (2006) Outcome effectiveness of therapeutic recreation camping program for adolescents living with cancer and diabetes. J Adolesc Health 39:445–447

Merckaert I et al (2010) Cancer patients’ desire for psychological support: prevalence and implications for screening patients’ psychological needs. Psycho-Oncology 19:141–149

Epelman C (2013) The adolescent and young adult with cancer: state of the art—psychosocial aspects. Curr Oncol Rep 15:325–331

Kroenke K et al (2009) An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: the PHQ-4. Psychosomatics 50(6):613–621

Merluzzi T, Martinez-Sanchez M (1997) Assessment of self-efficacy and coping with cancer: development and validation of the Cancer Behavior Inventory. Health Psychol 16(2):163–170

Heitzmann CA et al (2001) Assessing self-efficacy for coping with cancer: development and psychometric analysis of the brief version of the Cancer Behavior Inventory (CBI-B). Psycho-Oncology 10(3):206–217

Broadhead WE et al (1988) The Duke-UNC functional support questionnaire: measurement of social support in family medicine patients. Med Care 26(7):709–723

Applebaum AJ, Stein EM, Lord-Bessen J, Pessin H, Rosenfeld B, Breitbart W (2014) Optimism, social support, and mental health outcomes in patients with advanced cancer. Psycho-Oncology 23:299–306

McDowell I (2006) Measuring health: a guide to rating scales and questionnaires (3rd edition). Oxford University Press, New York

Gelman A, Hill J Data analysis using regression and multilevel/hierarchical models, 2006. Cambridge University Press

Steele F (2008) Multilevel models for longitudinal data. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: series A (statistics in society) 171(1):5–19

Moinpour CM et al (2000) Challenges posed by non-random missing quality of life data in an advanced-stage colorectal cancer clinical trial. Psycho-Oncology 9(4):340–354

Sansone RA, Sansone LA (2012) Antidepressant adherence: are patients taking their medications? Innovations in Clinical Neuroscience 9(4/5):41–46

Gaynes BN et al (2009) What did STAR*D teach us? Results from a large-scale, practical, clinical trial for patients with depression. Psychiatr Serv 60:1439–1445

Butow PN et al (2010) Review of adherence-related issues in adolescents and young adults with cancer. J Clin Oncol 28(32):4800–4809

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the First Descents staff and board of directors for their input and financial support of this work, as well as Sylvia Ciszek for her contributions to the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

B.Z. is a member of the Medical Advisory Board for First Descents but receives no compensation. No other authors have disclosures. B.Z. has full control of all primary data and agrees to allow the journal to review their data if requested.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zebrack, B., Kwak, M. & Sundstrom, L. First Descents, an adventure program for young adults with cancer: who benefits?. Support Care Cancer 25, 3665–3673 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-017-3792-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-017-3792-7