Abstract

In this update of our 2005 document, we used an evidence-based approach whenever possible to formulate recommendations, emphasizing the results of controlled trials concerning the best use of antiemetic agents for the prevention of emesis and nausea following anticancer chemotherapies of high emetic risk. A three-drug combination of a 5-hydroxytryptamine type 3 receptor (5-HT3) receptor antagonist, dexamethasone, and aprepitant beginning before chemotherapy and continuing for up to 4 days remains the standard of care. We address issues of dose, schedule, and route of administration of five selective 5-HT3 receptor antagonists. We conclude that, for each of these five drugs, there is a plateau in therapeutic efficacy above which further dose escalation does not improve outcome. In trials designed to prove the equivalence of palonosetron to ondansetron and granisetron, palonosetron proved superior in emesis prevention, while adverse effects were comparable. Furthermore, for all classes of antiemetic agents, a single dose is as effective as multiple doses or a continuous infusion. The oral route is as efficacious as the intravenous route of administration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A selective antagonist to the serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine type 3 receptor (5-HT3)) [17, 24, 47] combined with dexamethasone and the neurokinin-1 (NK1) receptor antagonist aprepitant has become the standard of care to prevent emesis following chemotherapy of high emetic risk. Although ondansetron, granisetron, tropisetron, and dolasetron differ in receptor specificity, potency, and plasma half-life [3, 47], each has demonstrated equivalent efficacy and adverse effects when used to prevent emesis following chemotherapy of high emetic risk. Recently, the 5-HT3 antagonist palonosetron has shown superior efficacy to granisetron when both were used in combination with dexamethasone in a trial designed to show equivalence [52]. This is the first conclusive demonstration of a meaningful efficacy difference when two 5-HT3 antagonists were compared. Despite these successes and widespread acceptance and availability of these agents, a number of controversies persist regarding the best way to use these agents in practice.

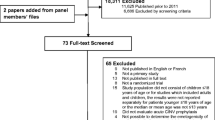

The “no emesis” rate for 5 days (120 h) following chemotherapy is the primary endpoint of modern antiemetic trials. Researchers also consider control during the initial 24 h after chemotherapy (acute emesis) and prevention from 24 to 120 h (delayed emesis) as additional parameters to be evaluated in antiemetic drug trials. This discussion will review issues of dose, schedule, and route of administration of five selective 5-HT3 receptor antagonists for the prevention of acute emesis caused by chemotherapy of high emetic risk. We also address issues of dose, schedule, and route of administration of dexamethasone and the NK1 antagonist aprepitant. We make recommendations for the use of these agents. This document relies heavily on this group's 2005 manuscript presenting our consensus synthesis and recommendations [37]. Many sections not requiring updating have been repeated here.

Dose of 5-HT3 receptor antagonists

The panel concluded that, despite preclinical differences, the 5-HT3 receptor antagonists are characterized clinically by a threshold effect for response, a modest dose-response curve, and a plateau in therapeutic efficacy extending over a several-fold range in dose. The therapeutic implications of these conclusions are that a higher dose or longer exposure is not necessarily better and that breakthrough emesis following the administration of a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist is more likely mediated by another mechanism rather than inadequate 5-HT3 receptor blockade [1, 2, 7, 8, 21, 56]. For ondansetron and granisetron, there is variability in the “approved” single doses for the prevention of acute emesis following chemotherapy of high emetic risk. In the USA, the approved dose of ondansetron (32 mg or approximately 0.45 mg/kg) is fourfold that of Europe (8 mg), while for granisetron, exactly the opposite is true with a 1-mg (0.01 mg/kg) dose in the USA vs a 3-mg (0.04 mg/kg) dose in Europe.

In view of the above considerations, analysis of the literature regarding dose was performed for the five 5-HT3 receptor antagonists in widest use. Both dose-response studies of individual agents and comparative trials between agents were considered. Study designs that incorporate issues of schedule are addressed below. Cisplatin serves as a paradigm for chemotherapy of high emetic risk. Moreover, cisplatin causes severe emesis in all patients who receive it at all doses in clinical use [39]. For these reasons, cisplatin has become the standard emetic stimulus in clinical trials of antiemetic agents. Further, all agree that an agent that lessens or prevents emesis following cisplatin will at least be as effective with other chemotherapeutic agents of similar or lesser emetic potential. Randomized studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of 5-HT3 receptor antagonists for the prevention of acute emesis following cisplatin [7, 9, 19, 42, 53, 55]. Furthermore, the addition of dexamethasone consistently improved efficacy compared to a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist alone, establishing this combination as a standard for patients receiving cisplatin-based therapy [25, 49]. Dose-ranging studies of these agents demonstrate a dose-response curve consistent with the conclusions discussed earlier [16, 17, 34, 35, 38, 49, 54, 57, 59]. There are conflicting data regarding the optimal single dose of ondansetron for prevention of acute emesis from cisplatin. While a study published by Beck et al. demonstrated that a 32-mg dose was superior to 8 mg, particularly in patients receiving high-dose cisplatin (>100 mg/m2); a similarly designed study by Seynaeve showed that the 8-mg dose was equally effective [4, 53]. In both studies, a single dose was equivalent to multiple dose schedules. Studies of the Italian Group for Antiemetic Research (IGAR) and from Ruff et al. also show a single 8-mg ondansetron equivalent to either a 32-mg ondansetron dose or 3 mg of granisetron, respectively [29, 51].

For granisetron, the evidence from two dose-response studies and comparative trials against ondansetron supports a dose of 0.01 mg/kg (commonly given as a 1-mg fixed dose) [45, 49, 54]. The dose-ranging studies of Navari and Riviere demonstrate that doses of 0.002 or 0.005 mg/kg are suboptimal while there is an effectiveness plateau above 0.01 mg/kg with a clinically insignificant higher no-emesis rate, at 0.04 mg/kg [46, 49]. The comparative trial by Navari supports the 0.01-mg/kg dose, with identical no-emesis rates for 0.01 vs 0.04 mg/kg in comparison to an approved and effective multiple-dose schedule of ondansetron (0.15 mg/kg for three doses) [46].

The dose-ranging study of Van Belle and the comparative trial by Marty both support a 5-mg single-dose administration of tropisetron as effective in highly emetogenic cisplatin-based chemotherapy, with the study of Van Belle suggesting no further improvement in efficacy at dose levels up to 40 mg [43, 59]. Dose-ranging studies of dolasetron did not define the lowest effective dose while the subsequent comparative trial of Hesketh supports a dose level of 1.8 mg/kg as effective, with no evidence of clinically significant improvement in efficacy at 2.4 mg/kg [27, 36, 57].

A dose-ranging study of palonosetron in patients receiving chemotherapy of high emetic risk (97% received cisplatin) tested intravenous doses from 0.0003 to 0.09 mg/kg and identified 0.003 and 0.0.01 mg/kg as the lowest effective palonosetron doses [11]. Three subsequent randomized trials compared a 0.25-mg fixed palonosetron dose, a 0.75-mg fixed palonosetron dose, and a standard comparator of either intravenous ondansetron 32 mg [1, 13] or intravenous dolasetron 100 mg [10]. The three studies confirmed the effectiveness and safety of palonosetron and showed no incremental benefit by increasing the single intravenous dose from 0.25 to 0.75 mg. A single intravenous dose of 0.25 mg of palonosetron is preferred and, at present, is the dose approved by regulatory authorities for the treatment of individuals receiving chemotherapy of high emetic risk. A 0.5-mg oral dosage form of palonosetron is available.

Dose of dexamethasone

A range of doses of dexamethasone, given either alone or in combination with a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist, have been tested as antiemetics. Many of these studies utilized a single 20-mg dose. The IGAR group has reported a comparison study of dexamethasone dosages ranging from 4 to 20 mg in patients receiving cisplatin [30]. They recommended a single 20-mg dose before chemotherapy based on their observations that the 20-mg dose had the highest numerical efficacy, and there was no difference in adverse effects among the doses tested [30].

The concomitant use of aprepitant, however, led to a change in the recommended dose of dexamethasone in clinical trials. The initial studies, which demonstrated improved antiemetic effects using aprepitant in combination with 5-HT3 antagonists and dexamethasone, administered dexamethasone at a 20-mg oral dose without difficulty [6, 44]. A pharmacokinetic study in healthy subjects found that aprepitant increased dexamethasone levels approximately twofold [5]. Because the differential exposure to dexamethasone could “theoretically confound the interpretation of the efficacy of aprepitant,” a reduction of the oral dexamethasone dose was made in the aprepitant arms of the randomized trials comparing a three-drug aprepitant regimen to the standard dexamethasone plus the ondansetron regimen [26, 48]. A 12-mg oral dose was given before cisplatin in the aprepitant arms in these studies. Although other dexamethasone doses may be appropriate, the 12-mg oral dose tested in two phase III studies [28, 48] is recommended.

Dose of aprepitant

Aprepitant is the first of a class of drugs that potently and selectively block the NK1 neurotransmitter receptor, the binding site of the regulatory peptide substance P. For the prevention of acute emesis following cisplatin, a randomized study evaluated oral pre-chemotherapy doses of aprepitant from 40 to 375 mg and concluded that a single 125-mg oral dose had “the most favorable benefit-risk profile [6].” This 125-mg dose was used in the randomized phase III comparison studies of aprepitant, and it is the only oral dose that has been approved by regulatory authorities. Although other aprepitant doses may be appropriate, the 125-mg oral aprepitant dose tested in two phase III studies [28, 48] is recommended. An intravenous (IV) formulation of aprepitant, fosaprepitant, is available at a dose of 115 mg [8, 40, 59].

Schedule of administration of 5-HT3 antagonist antiemetics

If given at an effective dose, a single dose provides adequate 5-HT3 receptor blockade for prevention of acute emesis. Clinical implications of this fact are that the administration of multiple doses is unnecessary and that breakthrough emesis during the first 24 h is likely related to other mediators/receptors. Multiple doses will only provide a better therapeutic outcome if the initial dose is suboptimal or if optimal therapeutic efficacy was dependent on either the plasma half-life or duration of receptor blockade during the acute phase. Substantial evidence supports these conclusions, particularly with ondansetron, the first 5-HT3 receptor antagonist developed. Early clinical trials of intravenous ondansetron with cisplatin explored a variety of schedule- related issues, including variable dosing intervals, number of doses, and schedules incorporating continuous infusion [22, 50]. In general, these studies demonstrated that shortening the dosing interval or increasing the number of doses did not improve efficacy. A continuous-infusion schedule following an 8-mg intravenous bolus was also found to be effective [42]. However, as demonstrated in the subsequent studies of Beck and Seynaeve, multiple-dose administration did not improve outcomes [4, 53]. Based on these observations, development of the other 5HT3 antagonists quickly evolved into determining optimal levels for intravenous single-dose administration. The recommended single doses of five 5-HT3 receptor antagonists are presented in the table.

Route of administration

Clinical outcomes with oral administration of 5-HT3 receptor antagonists and dexamethasone are equivalent to intravenous administration. Since oral administration is generally simpler and less resource-intensive, this route is preferable if the gastrointestinal tract is intact and compliance is assured. As a class, 5-HT3 antagonists exhibit good bioavailability when administered by the oral route, and the effectiveness of oral agents is equivalent to intravenous formulations. We recommend the administration of selective 5-HT3 antagonists by the oral route whenever appropriate. In all phase III studies, comparing oral 5-HT3 antagonists with intravenous formulations of antiemetics to treat cisplatin-induced emesis, control rates are comparable [15, 20].

Delayed emesis and nausea with chemotherapy of high emetic risk

Among the chemotherapy agents with high emetic risk, reliable data on the potential for delayed emesis is only available with cisplatin. Placebo-controlled trials have noted delayed emesis developing in 43–89% of patients following a variety of cisplatin doses [33]. A number of clinical factors have been identified as having value in predicting the development of delayed emesis. Female gender, higher cisplatin dose, and emesis during the first 24 h after chemotherapy are all associated with a higher risk of delayed emesis [23].

There is considerable evidence for the value of dexamethasone and the NK1 receptor antagonist aprepitant in preventing cisplatin-induced delayed emesis. A meta-analysis of results from 5,613 patients who received highly or moderately emetic chemotherapy for multiple types of cancer in 32 studies indicated that dexamethasone was superior to placebo or no treatment for complete protection from delayed emesis (OR = 2.06;95% CI 1.58–2.34). In the subset of patients just receiving highly emetic chemotherapy, dexamethasone was also superior to placebo or no treatment (OR = 1.93; 95% CI 1.58–2.34) [31].

The NK1 receptor antagonist aprepitant has also demonstrated significant activity in preventing cisplatin-induced delayed emesis. Three double-blind, phase III trials have evaluated the activity of aprepitant in preventing cisplatin-induced emesis [28, 32, 48]. The initial two trials had an identical study design and evaluated the control of delayed emesis as a secondary endpoint [28, 48]. During the delayed phase (days 2–5), patients received aprepitant on days 2 and 3 combined with dexamethasone on days 2–4 or dexamethasone alone on days 2, 3, and 4. Delayed complete response rates on the aprepitant and standard arms were 75% and 68%, compared with 56% and 47% in the two studies, respectively. Different antiemetic regimens were used for acute prophylaxis in these two trials with patients receiving aprepitant achieving superior control of emesis compared to the control group of ondansetron and dexamethasone alone. Thus, one can question whether a component of the improved efficacy of the aprepitant-containing arms during the delayed phase was due to a carryover effect from the different control rates on day 1. A subsequent analysis of the combined database from these two phase III trials strongly supported the conclusion that aprepitant provided protection against delayed vomiting regardless of the response in the acute phase [18]. In patients with acute vomiting, the proportion of patients with delayed vomiting was 85% and 68% on the control and aprepitant arms, respectively. In patients with no acute vomiting, the proportion with delayed vomiting was 33% and 17% on the control and aprepitant arms, respectively.

A third phase III trial conducted in patients receiving cisplatin used an identical study design to the other two phase III aprepitant trials with the exception that ondansetron was continued on days 2, 3, and 4 on the control arm [32]. Superior control of delayed emesis with an 11% numerical improvement was noted on the aprepitant vs control arm with delayed complete response rates of 74% and 63%, respectively (P = 0.004). A subsequent meta-analysis incorporating the data from all three aprepitant phase III trials revealed an absolute difference in complete control and no significant nausea during the delayed period (days 2–5) of 18% and 10%, respectively, favoring the aprepitant arms [14].

The 5-HT3 receptor antagonists dolasetron, granisetron, ondansetron, and tropisetron have demonstrated minimal activity in the prevention of cisplatin-induced delayed emesis. Trials have compared granisetron or ondansetron combined with dexamethasone with dexamethasone alone [12, 41, 58]. In all three studies, a total of 1,022 patients, the combination regimen was no better than dexamethasone alone. Data from two phase III trials with the 5-HT3 receptor antagonist palonosetron, however, suggest that this agent lessens cisplatin-induced delayed emesis. In a trial comparing palonosetron, either 0.25 or 0.75 mg, with 32 mg of ondansetron, all given as a single agent IV prior to cisplatin-based chemotherapy, both palonosetron doses resulted in numerically better control of delayed emesis compared to ondansetron [2]. Complete response rates were 45%, 48%, and 39% in the palonosetron 0.25 and 0.75 mg and ondansetron arms, respectively. A second phase III trial compared single-dose palonosetron, 0.75 mg IV with granisetron, 40 μg/kg IV, both combined with dexamethasone before cisplatin, in patients receiving cisplatin [52]. Patients also received dexamethasone 8 mg IV on days 2 and 3. Control of delayed emesis was significantly better with palonosetron compared to granisetron. Rates of no delayed emesis or antiemetic rescue were 54% vs 41% on the palonosetron and granisetron arms, respectively (P = 0.0012). In neither of the phase III trials of palonosetron with cisplatin-based chemotherapy was an NK1 receptor antagonist included. Thus, it remains unclear whether the differences in antiemetic efficacy between palonosetron and granisetron or ondansetron would have persisted in the presence of a NK1 antagonist.

Given the dependence of delayed emesis on control during the initial 24 h after chemotherapy, the panel recommends that optimal acute antiemetic prophylaxis be employed. For cisplatin and other chemotherapy agents with high emetic risk, this should include the three-drug combination of aprepitant, a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist and dexamethasone. In head-to-head comparisons between palonosetron and either granisetron or ondansetron, delayed emesis prevention was improved whether or not dexamethasone was given in addition. The combination of aprepitant and dexamethasone is recommended to prevent delayed emesis. Aprepitant should be used as a single 80-mg oral dose on days 2 and 3. No studies have been published evaluating the optimal dose of dexamethasone for the prevention of delayed emesis.

Consensus statements

Recommendation for the prevention of nausea and vomiting following chemotherapy of high emetic risk

To prevent acute and delayed vomiting and nausea following chemotherapy of high emetic risk, we recommend a multiday drug regimen including a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist, dexamethasone, and aprepitant beginning before chemotherapy

-

MASCC level of consensus: high

-

MASCC level of confidence: high

-

ESMO level of evidence: I

-

ESMO grade of recommendation: A

Patients are at risk for delayed emesis and must receive prophylactic antiemetics for 2 to 3 days following chemotherapy (Table 1).

Consensus principles of 5-HT3 receptor antagonist use to prevent acute and delayed nausea and emesis

-

Use the lowest tested fully effective dose.

-

No schedule better than a single dose beginning before chemotherapy.

-

Adverse effects of these agents are comparable.

-

Intravenous and oral formulations are equally effective and safe.

-

Give with dexamethasone and aprepitant beginning before chemotherapy.

-

MASCC level of consensus: high

-

MASCC level of confidence: moderate

-

ESMO level of evidence: I

-

ESMO level of confidence: A

-

Summary and conclusions

Consensus recommendations for the doses of each specific antiemetic agent used to prevent acute emesis from chemotherapy of high emetic risk are presented in Table 1. Whenever possible, these recommendations represent an analysis of literature using an evidence-based approach. In addition, they also reflect the input of the discussants and participants during this consensus conference.

The 5-HT3 receptor antagonists, dexamethasone, and the NK1 receptor antagonists have substantially improved our ability to prevent acute and delayed emesis and nausea caused by chemotherapy of high emetic risk. These three classes used in combination are the standard of care in patients receiving high emetic risk chemotherapy including cisplatin. Nevertheless, many patients continue to experience vomiting and nausea despite receiving optimal prophylaxis. It is likely that these episodes are mediated through mechanisms unaffected by the combined effects of dexamethasone along with 5-HT3 and NK1 receptor blockade. Further improvements can only occur after a better understanding of the underlying pathophysiology of emesis caused by chemotherapy allows us to create new drugs that more effectively silence the neural signals that trigger nausea and vomiting. Only then will we be able to eliminate emesis caused by cancer treatment. In the meantime, using the available agents according to treatment guidelines, beginning before the first dose of chemotherapy and continuing for 4 days, is the best strategy to maximally lessen the burden of nausea and emesis for every person receiving chemotherapy of high emetic risk.

References

Aapro M, Selak M, Lichinitser D, Santini A, Macciocchi A, Klinik A, Blokhin NN (2003) Palonosetron (PALO) is more effective than ondansetron (OND) in preventing chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) in patients receiving moderately emetogenic chemotherapy (MEC): Results of a Phase III trial. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 22:726

Aapro MS, Grunberg SM, Manikhas GM, Olivares G, Suarez T, Tjulandin SA, Bertoli LF, Yunus F, Morrica B, Lordick F, Macciocchi A (2006) A phase III, double-blind, randomized trial of palonosetron compared with ondansetron in preventing chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting following highly emetogenic chemotherapy. Ann Oncol 17:1441–1449

Andrews PLR, Davis CJ (1993) The mechanism of emesis induced by anti-cancer therapies. In: Andrews PLR, Sanger GJ (eds) Emesis in anticancer therapy mechanisms and treatment. Chapman & Hall, London, pp 14–17

Beck TM, Hesketh PJ, Madajewicz S, Navari RM, Pendergrass K, Lester EP, Kish JA, Murphy WK, Hainsworth JD, Gandara DR, Bricker LJ, Keller AM, Mortimer J, Galvin DV, House KW, Bryson JC (1992) Stratified, randomized, double-blind comparison of intravenous ondansetron administered as a multiple-dose regimen versus two single-dose regimens in the prevention of cisplatin-induced nausea and vomiting. J Clin Oncol 10:1969–1975

Blum RA, Majumdar A, McCrea J et al (2003) Effects of aprepitant on the pharmacokinetics of ondansetron and granisetron in healthy subjects. Clin Ther 25:1407–1419

Chawla SP, Grunberg SM, Gralla RJ, Hesketh PJ, Rittenberg C, Elmer ME, Schmidt C, Taylor A, Carides AD, Evans JK, Horgan KJ (2003) Establishing the dose of the oral NK1 antagonist aprepitant for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Cancer 97:2290–2300

Chevalier B (1990) Efficacy and safety of granisetron compared with high-dose metoclopramide plus dexamethasone in patients receiving high-dose cisplatin in a single-blind study. Eur J Cancer 26:S33–S36

Cocquyt V, VanBelle S, Reinhardt RR, Decramer MLA, O'Brien M, Schellens JHM, Borms M, Verbeke L, VanAelst F, DeSmet M, Carides AD, Eldridge K, Gertz BJ (2001) Comparison of L-758,298, a prodrug for the selective neurokinin-1 antagonist, L-754-030, with ondansetron for the prevention of cisplatin-induced emesis. Eur J Cancer 37:835–842

DeMulder PH, Seynaeve C, Vermorken JB, Van Liessum LPA, Mols JS, Allman EL, Beranek P, Verweij J (1990) Ondansetron compared with high-dose metoclopramide in prophylaxis of acute and delayed cisplatin-induced nausea and vomiting: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, crossover study. Ann Intern Med 113:834–840

Eisenberg P, Figueroa-Vadillo J, Zamora R, Charu V, Hajdenberg J, Cartmell A, Macciocchi A, Grunberg S (2003) Palonosetron study G. improved prevention of moderately emetogenic chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting with palonosetron, a pharmacologically novel 5-HT3 receptor antagonist: results of a phase III, single-dose trial versus dolasetron. Cancer 98:2473–2482

Eisenberg P, MacKintosh FR, Ritch P, Cornett PA, Macciocchi A (2004) Efficacy, safety and pharmacokinetics of palonosetron in patients receiving highly emetogenic cisplatin-based chemotherapy: a dose-ranging clinical study. Ann Oncol 15:330–337

Goedhals L, Heron JF, Kleisbauer JP, Pagani O, Sessa C (1998) Control of delayed nausea and vomiting with granisetron plus dexamethasone or dexamethasone alone in patients receiving highly emetogenic chemotherapy: A double-blind placebo-controlled, comparative study. Ann Oncol 6:661–666

Gralla R, Lichinitser M, Van Der Vegt S, Sleeboom H, Mezger J, Peschel C, Tonini G, Labianca R, Macciocchi A, Aapro M (2003) Palonosetron improves prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting following moderately emetogenic chemotherapy: Results of a double-blind randomized phase III trial comparing single doses of palonosetron with ondansetron. Ann Oncol 14:1570–1577

Gralla RJ, Raftopoulos H, Bria E, ete al (2008) Cisplatin in non-small cell lung cancer: reducing the most prominent toxicity, emesis. Results of a meta-analysis with 1527 patients in randomized clinical trials testing the addition of an NK1 antagonist J Clin Oncol 26.

Gralla RJ, Tyson LB, Kris MG, Clark RA (1987) The management of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Med Clin North Am 71:289–301

Grunberg SM, Hesketh PJ, Carides AD et al (2003) Relationships between the incidence and control of cisplatin-induced acute vomiting and delayed vomiting: Analysis of pooled data from two phase III studies of the NK-1 antagonist aprepitant. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 22:2931a

Grunberg SM, Stevenson LL, Russell CA, McDermed JE (1989) Dose ranging phase I study of the serotonin antagonist GR38032F for prevention of cisplatin-induced nausea and vomiting. J Clin Oncol 7:1137–1141

Grunberg SM, Vanden Burgt JA, Berry S, et al (2004) Prevention of delayed nausea and vomiting (D-CNV): Carryover effect analysis of pooled data from 2 phase III studies of palonosetron (PALO).

Hainsworth J, Harvey W, Pendergrass K, Kasimis B, Oblon D, Monaghan G, Gandara D, Hesketh P, Khojasteh A, Harker G (1991) A single-blind comparison of intravenous ondansetron, a selective serotonin antagonist, with intravenous metoclopramide in the prevention of nausea and vomiting associated with high-dose cisplatin chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 9:721–728

Heron JF (1995) Single-agent oral granisetron for the prevention of acute cisplatin-induced emesis: a double-blind, randomized comparison with granisetron plus dexamethasone and high-dose metoclopramide plus dexamethasone. Semin Oncol 22:24–30

Herrstedt J (1996) New perspectives in antiemetic treatment support care. Cancer 4:416–419

Hesketh PA, Gandara DR, Hesketh AM, Facada A, Perez EA, Webber LM, Martin LA, Cramer MB, Hahne WF (1996) Dose-ranging evaluation of the antiemetic efficacy of intravenous dolasetron in patients receiving chemotherapy with doxorubicin or cyclophosphamide Support Care Cancer 4.

Hesketh PJ (2008) Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. N Engl J Med 358:2482–2494

Hesketh PJ, Gandara DR (1991) Serotonin antagonists: a new class of antiemetic agents. J Natl Cancer Inst 83:613–620

Hesketh PJ, Gandara DR, Hainsworth J, Edelman M, Webber LM, McManus M (1996) Addition of the dopamine D2 antagonist prochlorperazine to granisetron/dexamethasone: improved control of acute emesis fron high-dose cisplatin. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 15:540

Hesketh PJ, Gralla RJ, Webb RT, Ueno W, DelPrete S, Bachinsky ME, Dirlam NL, Stack CB, Silberman SL (1999) Randomized Phase II study of the neurokinin 1 receptor antagonist CJ-11,974 in the control of cisplatin-induced emesis. J Clin Oncol 17:338–343

Hesketh PJ, Murphy WK, Lester EP, Gandara DR, Khojasteh A, Tapazoglou E, Sartiano GP, White DR, Werner K, Chubb JM (1989) GR 38032F (GR-C507/75): a novel compound effective in the prevention of acute cisplatin-induced emesis. J Clin Oncol 7:700–705

Hesketh PJ, Van Belle S, Aapro M, Tattersall FD, Naylor RJ, Hargreaves R, Carides AD, Evans JK, Horgan KJ (2003) Differential involvement of neurotransmitters through the time course of cisplatin-induced emesis as revealed by therapy with specific receptor antagonists. Eur J Cancer 39:1074–1080

IGAR (1995) Persistence of efficacy of three antiemetic regimens and prognostic factors in patients undergoing moderately emetogenic chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 13:2417–2426

IGAR (1998) Double-blind, dose-finding study of four intravenous doses of dexamethasone in the prevention of cisplatin-induced acute emesis. J Clin Oncol 16:2937–2942

Ioannidis JP, Hesketh PJ, Lau J (2000) Contribution of dexamethasone to control of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: a meta-analysis of randomized evidence. J Clin Oncol 18:3409–3422

Jordan K, Schmoll HJ, Aapro MS (2007) Comparative activity of antiemetic drugs. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 61:162–175

Kris MG, Cubeddu LX, Gralla RJ, Cupissol D, Tyson LB, Venkatraman E, Homesley HD (1996) Are more antiemetic trials with placebo necessary? Report of patient data from randomized trials of placebo antiemetics with cisplatin. Cancer 78:2193–2198

Kris MG, Gralla RJ, Clark RA, Tyson LB, OConnell JP, Wertheim MS, Kelsen DP (1985) Incidence, course, and severity of delayed nausea and vomiting following the administration of high-dose cisplatin. J Clin Oncol 3:1379–1384

Kris MG, Gralla RJ, Tyson LB, Clark RA, Kelsen DP, Reilly LK, Groshen S, Bosl GJ, Kalman LA (1985) Improved control of cisplatin-induced emesis with high-dose metoclopramide and with combinations of metoclopramide, dexamethasone, and diphenhydramine. results of consecutive trials in 255 patients. Cancer 55:527–534

Kris MG, Grunberg SM, Gralla RJ, Baltzer L, Zaretsky SA, Lifsey D, Tyson LB, Schmidt L, Hahne WF (1994) Dose-ranging evaluation of the serotonin antagonist dolasetron mesylate in patients receiving high-dose cisplatin. J Clin Oncol 12:1045–1049

Kris MG, Hesketh PJ, Herrstedt J, Rittenberg C, Einhorn LH, Grunberg S, Koeller J, Olver I, Borjeson S, Ballatori E (2005) Consensus proposals for the prevention of acute and delayed vomiting and nausea following high-emetic-risk chemotherapy Support Care. Cancer 13:85–96

Kris MG, Pisters KMW, Hinkley L (1994) Delayed emesis following anticancer chemotherapy support care. Cancer 2:297–300

Kris MG, Radford J, Pizzo B, et al (1996) Dose ranging antiemetic trial of the NK-1 receptor antagonist CP-122,721: A new approach for acute and delayed emesis following cisplatin Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol: 547

Lasseter KC, Gambale J, Jin B, Bergman A, Constanzer M, Dru J, Han TH, Majumdar A, Evans JK, Murphy MG (2007) Tolerability of fosaprepitant and bioequivalency to aprepitant in healthy subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol 47:834–840

Latreille J, Pater J, Johnston D, Laberge F, Stewart D, Rusthoven J, Hoskins P, Findlay B, McMurtrie E, Yelle L, Williams C, Walde D, Ernst S, Dhaliwal H, Warr D, Shepherd F, Mee D, Nishimura L, Osoba D, Zee B (1998) Use of dexamethasone and granisetron in the control of delayed emesis for patients who receive highly emetogenic chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 16:1174–1178

Marty M, J-p K, Fournet P, Vergnenegro A, Carics P, Loria-Kanza Y, Simonetta C, Bruijn KM (1995) Is Navoban (tropisetron) as effective as Zofran (ondansetron) in cisplatin-induced emesis? Anticancer Drugs 6:15–21

Marty M, Pouillart P, Scholl S, Droz JP, Azab M, Brion N, Pujade LE, Paule B, Paes D, Bons J (1990) Comparison of the 5-hydroxytryptamine 3 (serotonin) antagonist ondansetron (GR 38032F) with high-dose metoclopramide in the control of cisplatin-induced emesis. N Engl J Med 322:816–821

Navari R, Gandara D, Hesketh P, Hall S, Mailliard J, Ritter H, Friedman C, Fitts D (1995) Comparative clinical trial of granisetron and ondansetron in the prophylaxis of cisplatin-induced emesis. J Clin Oncol 13:1242–1248

Navari RM, Madajewicz S, Anderson N, Tchekmedyian NS, Whaley W, Garewal H, Beck TM, Chang AY, Greenberg B, Caldwell KC, Huffman DH, Gould JR, Carron G, Ossi M, Anderson EM (1995) Oral ondansetron for the control of cisplatin-induced delayed emesis: A large, multicenter, double-blind, randomized comparative trial of ondansetron versus placebo. J Clin Oncol 13:2408–2416

Navari RM, Reinhardt RR, Gralla RJ, Kris MG, Hesketh PJ, Khojasteh A, Kindler H, Gtote T, Carides AD, Gertz BJ (1999) Prevention of cisplatin-induced emesis by a neurokinin-1-receptor antagonist (Letter-authors reply). N Engl J Med 340:1927–1928

Perez EA (1995) Review of the preclinical pharmacology and comparative efficacy of 5-hydroxyoyptamine-3 receptor antagonists for chemotherapy-induced emesis. J Clin Oncol 13:1036–1043

Poli-Bigelli S, Rodrigues-Pereira J, Carides AD, Julie Ma G, Eldridge K, Hipple A, Evans JK, Horgan KJ, Lawson F (2003) Addition of the neurokinin 1 receptor antagonist aprepitant to standard antiemetic therapy improves control of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Results from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in Latin America. Cancer 97:3090–3098

Riviere A, on behalf of the Granisetron Study Group (1994) Dose finding study of granisetron in patients receiving high-dose cisplatin chemotherapy. Br J Cancer 69:967–971

Roila F, Del Favero A, Gralla RJ, Tonato M (1998) Prevention of chemotherapy- and radiotherapy-induced emesis: Results of the Perugia Consensus Conference. Ann Oncol 9:811–819

Ruff P, Paska W, Goedhals L, Pouiliart P, Riviere A, on behalf of the Granisetron Study Group, Vorolieof D, Bloch, Jones A, Martin L, Brunet R, Butcher, Forster J, McQuade B, on behalf of the Ondansetron and Granisetron Emesis Study Group (1994) Ondansetron compared with granisetron in the prophylaxis of cisplatin-induced acute emesis: a multicenter double-blind, randomized, parallel-group study. Oncology 51:113–118

Saito M, Aogi K, Sekine I, Yoshizawa H, Yanagita Y, Sakai H, Inoue K, Kitagawa C, Ogura T, Mitsuhashi S (2009) Palonosetron plus dexamethasone versus granisetron plus dexamethasone for prevention of nausea and vomiting during chemotherapy: a double-blind, double-dummy, randomised, comparative phase III trial the lancetcom/oncology.

Seynaeve C, Schuller J, Buser K, Porteder H, Van Belle S, Sevelda P, Christmann D, Schmidt M, Kitchener H, pacs D, de Mulder PHM, on behalf of the Ondansetron Study Group (1992) Comparison of the antiemetic efficacy of ondansetron given as either a continuous infusion or a single intravenous dose, in acute cisplatin-induced emesis. A multicenter, double-blind, randomized, parallel group study. Br J Cancer 66:192–197

Soukop J, on behalf of the Granisetron Study Group (1994) A dose-finding study of granisetron, a novel antiemetic, in patients receiving high-dose cisplatin Support Care. Cancer 2:177–183

Soukop M, McQuade B, Hunter E et al (1992) Ondansetron compared with metoclopramide in the control of emesis and quality of life during repeated chemotherapy for breast cancer. Oncology 49:295–304

Tattersall FD, Rycroft W, Hill RG, Hargreaves RJ (1994) Enantioselective inhibition of apomorphine-induced emesis in the ferret by the neurokinin receptor antagonist CP-99,994. Neuropharmacology 33:259–260

Thant M, Pendergras K, Harman G, Modiano M, Martin L, DuBois D, Cramer M, Hahne W (1996) Double-blind, randomized study of the dose-response relationship across five single doses of IV dolasetron mesylate (DM) for prevention of acute nausea and vomiting (ANC) after cisplatin chemotherapy (CCT). Proc ASCO 15:533

Tsukada H, Hirose T, Yokoyama A, Kurita Y (2001) Randomized comparison of ondansetron plus dexamethasone with dexamethasone alone for the control of delayed cisplatin-induced emesis. Eur J Cancer 37:2398–2404

VanBelle S, Lichinitser MR, Navari RM, Garin AM, Decramer MLA, Rivier A, Thant M, Brestan E, Bui B, Eldridge K, DeSmet M, Michiels N, Reinhardt RR, Carides AD, Evans JK, Gertz BJ (2002) Prevention of cisplatin-induced acute and delayed emesis by the selective neurokinin-1 antagonists, L-758-298 and MK-869. Amer Cancer Soc 94:3032–3041

Conflict of interest statement

The following authors either received research funding, honoraria, or have been a consultant to or an expert witness for: Kris: GSK, Merck; Tonato: no conflicts reported; Bria: Helsinn, Merck; Ballatori: Helsinn; Espersen: no conflicts reported; Herrstedt: GSK, Helsinn, Merck; Rittenberg: Merck; Grunberg: GSK, Helsinn, Merck, Eisai, Prostrakan; Saito: no conflicts reported; Morrow: GSK, Helsinn, Merck, Eisai; Hesketh: GSK, Merck, Eisai; Einhorn (wife) has been an investor in GSK.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kris, M.G., Tonato, M., Bria, E. et al. Consensus recommendations for the prevention of vomiting and nausea following high-emetic-risk chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer 19 (Suppl 1), 25–32 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-010-0976-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-010-0976-9