Abstract

The alluvial backwater areas of the Danube are valuable ecological habitats containing important drinking water resources. Due to the river regulation and the construction of power plants, the river water levels and natural dynamics of the backwater areas continuously decline, threatening their typical characteristics. The aim of this study was to evaluate how an increased connectivity of the backwater branch located in a nature-protected riverine floodplain (enabled by diverting river water into the backwater system via a weir) affects the microbiological quality of groundwater resources. The defined quality criterion was that the diversion measures must not lead to an increased detection frequency of faecal indicators in groundwater. The microbiological water quality of the Danube, its backwater branch and the groundwater was analysed from 2010 to 2013. E. coli was selected as bacterial indicator for recent faecal pollution. C. perfringens (spores) was analysed as indicator for persistent faecal pollution and potentially occurring pathogenic protozoa. We simulated the microbial transport from the Danube and the backwater river into groundwater using a 3‑D unsaturated-saturated groundwater model coupled with 2‑D hydrodynamic flow simulations. Scenarios for no diversion measures were compared with scenarios for an additional discharge of 3, 20 and 80 m3/s from the Danube River into the backwater branch. While the additional discharge of 20 and 80 m3/s of Danube water into the floodplain strongly improved the ecological status according to ecological habitat models, the hydraulic transport simulations showed that this would result in a deterioration of the microbiological quality of groundwater resources. The presented approach shows how hydraulic transport modelling and microbiological analyses can be combined to support decision-making.

Zusammenfassung

Die Flussauen der Donau sind wertvolle ökologische Lebensräume und enthalten wichtige Trinkwasserressourcen. Durch Flussregulierungen und den Betrieb von Kraftwerken nehmen der Wasserstand und die natürliche Dynamik in den angrenzenden Auengebieten kontinuierlich ab, was die natürliche Charakteristik dieser Landschaftstypen gefährdet. Das Ziel dieser Studie war es zu untersuchen, wie eine verbesserte Anbindung eines Auengebiets durch Einleitung von Donauwasser über ein Wehr die mikrobiologische Qualität der Grundwasserressourcen beeinflusst. Das Qualitätskriterium war so definiert, dass die Anbindungsmaßnahmen nicht zu einem häufigeren Nachweis von Fäkalindikatoren im Grundwasser führen dürfen. Die mikrobiologische Wasserqualität der Donau und des Seitenarms im Untersuchungsgebiet wurde von 2010 bis 2013 analysiert. E. coli wurde als bakterieller Indikator für rezente fäkale Verunreinigung gewählt. C. perfringens (Sporen) wurden als Indikatoren für persistente fäkale Verunreinigung und potenziell vorkommende pathogene Protozoen gewählt. Wir simulierten den mikrobiellen Transport von der Donau und dem Altarm im Auengebiet ins Grundwasser. Dazu verwendeten wir ein 3‑D ungesättigt-gesättigtes Grundwassermodell, gekoppelt mit einem 2‑D hydrodynamischen Strömungsmodell. Wir verglichen Modellszenarien ohne Anbindungsmaßnahmen mit welchen mit zusätzlichen Einleitungen von 3, 20 und 80 m3/s von der Donau in den Seitenarm. Während ökologische Habitatmodelle zeigten, dass eine zusätzliche Einleitung von 20 und 80 m3/s Donauwasser in die Au den ökologischen Zustand stark verbesserte, zeigten die hydraulischen Transportsimulationen, dass diese zu einer Verschlechterung der mikrobiologischen Qualität der Grundwasserressourcen führen würde. Der vorgestellte methodische Ansatz zeigt, wie hydraulische Transportmodellierung und mikrobiologische Analysen kombiniert werden können, um die Entscheidungsfindung bei der Planung zu unterstützen.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The wetlands of the Danube play an important role for recreation and drinking water supply. These areas offer important habitats for rare and protected wildlife and plant species and are part of a national park following the European guidelines such as 2006/105/EG. The groundwater bodies are important resources for drinking water supply. The preservation of the natural characteristics and the ecological functions of the Danube wetlands are threatened. The elevation of the Danube riverbed progressively declined due to the regulation of river water levels through the operation of power plants. The regulation of the river has further led to a declining connectivity of the backwater areas. Consequently, the groundwater levels and dynamics have declined, and the backwater areas are silting up, which causes ecological deficits. The aim of a sustainable water resource management is thus to improve the hydrological conditions and preserve the ecological functioning of such areas. One possible measure is to divert river water into the backwater branches or to improve the connectivity of the side branches. Such measures could support the development of a more dynamic alluvial backwater area with a larger biodiversity and help preserving the high value of the natural areas in the long term. Such measures, however, must be in line with the Water Rights Act (1959) and must not lead to a restriction of drinking water production. In Austria, groundwater used as drinking water resource must have sufficient quality to require no further treatment. According to the Austrian Drinking Water Ordinance (2001) and the Water Rights Act (1959), faecal pollution is not permitted in drinking water and protected groundwater resources. The compliance with this requirement is assumed fulfilled when standard faecal indicators are not detectable in 100 ml sample volume.

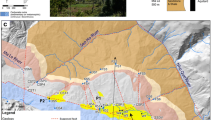

The wetlands of the Danube inhabit abundant wildlife including ruminants, wild boars and birds (Arnberger et al. 2009; Frühauf and Sabathy 2006; Parz-Gollner 2006). Together with the discharges of treated human wastewater along the Danube upstream, these sources potentially contribute to faecal pollution of the surface water bodies. The aim of this study was to evaluate the impact of diverting Danube water into an alluvial backwater area (BA, additionally to the normal influx via the entry point during floods, Fig. 1) on the microbiological groundwater quality based on hydrodynamic surface water and hydraulic groundwater modelling. We investigated different possible scenarios to divert Danube water into the study area. The investigated microbiological parameters were selected according to the Austrian Drinking Water Ordinance (2001). E. coli was selected as bacterial indicator for recent faecal pollution. C. perfringens (spores) was investigated as indicator to include also persistent faecal excreted pathogens, i.e. protozoan cysts and oocysts. To evaluate the effect of the diversion measures, the criterion was to achieve no increased detection frequency of the faecal indicators in the groundwater samples within the framework of the standard monitoring in comparison with the reference case of no diversion.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Hydrological characteristics of the study site

The study area is a typical urban riverine wetland. It is located on the left side of the Danube River at the border to Vienna and is approximately 12 km2 in size (Fig. 1). The Danube is regulated through the operation of a power plant at the study site. Within the city’s borders, the Danube Island separates the New Danube from the Danube. Due to the regulation of the Danube, and the construction of a flood protection dam alongside the Danube, the backwater only connects with the main stream during sporadic high water events (see entry point in Fig. 1). In this case, Danube water enters the main backwater branch at its downstream end through a levee opening. When the flood reaches its peak, the flow direction reverses, and the water flows back towards the Danube River. The network consists of numerous further partly disconnected side branches and isolated ponds.

2.2 Microbiological analysis

E. coli and C. perfringens (spores) were analysed monthly from 1‑L grab samples taken at an observation point LSW1 on the left side of the Danube from 2010 to 2012 and at observation points LSW2–9 in the backwaters from 2010 to 2013 (Fig. 1). E. coli was further analysed at an official bathing site of the New Danube (ND, Fig. 1) in the months from May to September from 2010 to 2013. E. coli and C. perfringens (spores) were further analysed in groundwater samples at 10 piezometers located along transects to the pumping wells from 2010 to 2013. E. coli and C. perfringens (spores) were analysed following the methods ISO 16649‑2 (2001) and ISO 14189 (2013). Values reported in this paper are presented as colony forming units (CFU)/100 mL. At the New Danube (ND, Fig. 1), E. coli was analysed following the method ISO 9308‑3 (1998). Values are presented as most probable numbers (MPN)/100 mL.

2.3 Groundwater flow model

For simulating the groundwater flow and microbial transport, it was important to account for the groundwater exchange with the Danube and backwaters, the 3‑D groundwater flow conditions, the strongly varying topography, the geological layers and the unsaturated zone. Groundwater flow and transport were simulated using SUTRA 2.2 (Voss and Provost 2010). The 3‑D governing equation for the transient variably saturated water flow is

with the hydraulic pressure p [kg/m·s2], the 3‑D aquifer permeability matrix K [m2], the gravity vector g [9.81 m/s2], the water content θw [−], the water density ρ [kg/m3], the specific yield θ [−], the fluid viscosity μ [kg/m·s], and qw [L/m3·s] the fluid mass source. The groundwater model domain comprises an area of 52 km2, limited by a Danube River stretch of 9 km length (Fig. 1). The dimensions of the aquifers were chosen large enough to avoid errors induced from boundary effects. The horizontal discretization of the numerical elements vary from 5 to 100 m. Along the banks of the Danube river and the floodplain river and in the vicinity of the drinking water wells, smaller cell sizes were used to minimize the effect of numerical dispersion on transport simulations (Derx et al. 2013). The aquifer beneath the riverbed was 10 m deep on average and was discretized into 15 layers at an interval from 1 to 90 cm in the upper layers and 0.3 to 6 m in the lower layers. The model consisted of approximately 520,000 elements in total.

The groundwater model was coupled with a 2‑D hydrodynamic flow model (CCHE2D version 2.0, National Center for Computational Hydroscience and Engineering, University of Mississippi). The simulated surface water levels were set as head boundary conditions along the Danube and in the backwaters. A detailed description of the model set up and calibration is given by Frick et al. (2020). The Danube boundary was approximately 150 m wide, between the river centerline and a steep river embankment. Outside the hydrodynamic model domain, the head boundary conditions along the Danube River were set to interpolated values of the characteristic Danube water levels to the hourly-observed water levels at the Danube gauge Fischamend at river-km 1907.90 (KWD 2010). The backwater area and the Danube River bank were defined as a transition zone alternating between submerged and dry during the flood events (Fig. 1), as described by Derx et al. (2013). All other vertical head boundary conditions were interpolated from measured heads at 26 groundwater piezometers located within 5 km distance. The top layer in the land zone was set to no-flow, assuming a negligible groundwater recharge from precipitation. The bottom boundary of the domain was defined to represent the aquitard. Groundwater was abstracted from five production wells. Numerical nodes that were located within a circle of 50 m in diameter around each well at the bottom model boundary represented the horizontal collector pipes extending radially at the bottom of the aquifer. Pumping rates of 330, 250, 280, 180 and 140 l/s at wells PGAW 1–5 were assumed, respectively (Fig. 1). Transient boundary conditions were set at hourly time steps. As initial pressure heads and for simulations of steady flow conditions, simulations were performed over 1.5 years holding all boundary conditions constant.

The groundwater flow model was calibrated by adjusting the aquifer permeability within zones and fitting the simulated to the observed hourly levels at 46 groundwater piezometers distributed within the model domain. Care was taken to consolidate the same values of permeability into large regions. The aquifer permeability was set vertically anisotropic with an anisotropy ratio of 0.1 (Eq. 1). We assumed a constant specific yield of 0.15 (de Marsily 1986). Water saturation and permeability in the unsaturated zone were calculated by using the model of van Genuchten (1980) using parameter values as obtained by the Rosetta Lite program (Schaap et al. 2001) for the sand textural class of the USDA triangle. The permeability of the confined layer was set to 1 × 10−12 m2 according to results of infiltration tests and sieve analyses. To consider clogging processes, very low permeabilities of 10−12 to 10−13 m2 were assigned to the uppermost 50 cm of the riverbed and riverbank in parts of the model domain, along the bed of the main and ephemeral side backwater branches according to a manual survey (Walter Reckendorfer and Raimund Taschke, personal communication). Two calibration periods were chosen, one period during mean steady flow conditions and one period during a flood event in January 2011, corresponding to a return period of 9 years. The model calibration resulted in an aquifer permeability ranging from 1 × 10−11 to 1 × 10−9 m2. As a measure of model performance, we calculated the Nash-Sutcliff coefficients resulting in values above 0.87 at 78% of the piezometer locations (Fig. 2).

2.4 Microbial transport model in groundwater

We used the calibrated groundwater model to simulate the transport of E. coli and C. perfringens (spores) by solving the 3‑D advection-dispersion equation with first order removal rates μw [1/d] (Voss and Provost 2010)

with the microbial concentration in groundwater C [CFU/100 mL], the simulation time t, the soil density ρs [kg/m3], the 3‑D dispersion tensor D [m2/s], and the pore velocity vector v [m/s]. The microbial removal rates [1/s] are combined filtration rates by retention and inactivation. Filtration rates of E. coli ranged from 0.4–2.5 1/m in sand and gravel (Artz et al. 2005; Smith et al. 1985). Using the most conservative value and a mean simulated pore velocity of 10−4 m/s during the calibration, this converts to 2.3 · 0.4 · 10−4 = 9.2 · 10−5 1/s. For C. perfringens (spores), the same removal rate was assumed as for E. coli. The inactivation rate of E. coli in groundwater was set to 0.18 1/d (Nasser et al. 1993). For C. perfringens (spores), an inactivation rate of 0 1/d was assumed. According to injection tracer tests in the field, microbial transport often follows preferential flow paths (Pang 2009). To represent this behavior and to keep the numerical dispersion small, the dispersion was set so that the criterion \(\boldsymbol{v}\cdot x/\boldsymbol{D}\leq 2\) was met (Kinzelbach 1987), with x [m] being the maximum extent of a numerical element. D is the product of longitudinal and transversal dispersivity and the pore velocity v. In the well capture zones of PGAW 1–5, the longitudinal and transversal dispersivity were set to 20 and 1 m, respectively. A vertical anisotropy ratio of 0.1 was assumed in consistency with the sediment origin of the aquifer (Gelhar et al. 1992).

2.5 Simulated scenarios

Through the combination of hydrodynamic surface water and hydraulic groundwater models, we investigated scenarios of different diversion rates into the backwater branch. The diversion measures were then evaluated based on the criterion that they must not lead to a significant (p < 0.05) increase in detection rates of faecal indicators in groundwater according to the Austrian Drinking Water Ordinance (2001). One possible scenario was to pipe 3 m3/s surplus water of the New Danube (Fig. 1) in free descent into the backwater branch. Additionally, we investigated scenarios to connect the backwater branch with the Danube in order to restore the natural water level dynamics. The possible scenarios included an additionally discharge of 3 m3/s, 20 m3/s and 80 m3/s of Danube water into the backwater branch via weirs. Such measures would require substantial construction works to lower the existing traverses along the backwater river, and to widen the current entry point of the Danube during floods (Fig. 1). The transport of E. coli and C. perfringens (spores) was simulated for hydrological conditions at low water level (LW), at mean water level (MW), and at mean water level plus 1 m (MW + 1) (Table 1). In all scenarios, the initial concentrations of both microbial parameters were assumed to be 0 CFU/100 mL in groundwater, which complies with the measured concentrations of faecal indicators in groundwater over 97–98% of the time (Sect. 3.1). The transport simulation time was 60 days. All simulations were run on the computer aided engineering cluster (cae.zserv and phoenix2.zserv, TU Wien). The computational time for each scenario was several hours.

In order to evaluate the investigated scenarios, the modelling results are presented as difference between simulated faecal indicator concentrations with and without diverting Danube water into the backwater area. These differences are presented in ranges from 10−3 to 102 CFU/100 mL in Figs. 4, 5, 6 and 7. An increase in faecal indicator concentrations above 10−2 CFU/100 mL would lead to higher detection rates during routine monitoring in the short term (within weeks to months), considering the frequency of standard microbiological analyses of groundwater. An increase in concentrations in the range from 10−3 to 10−2 CFU/100 mL would lead to higher detection frequencies during routine monitoring in the midterm (several months to one year). Increases in faecal indicator concentrations in the range from 10−3 to 102 CFU/100 mL are therefore not acceptable considering the criteria of no deterioration of the microbiological groundwater quality. The Kruskal-Wallis test was performed to evaluate if the differences in concentrations were significant (p < 0.05).

3 Results

3.1 Microbiological water quality

The monitored concentrations in surface water showed similar patterns for E. coli and C. perfringens (spores). The sampling sites at the Danube revealed a moderate faecal pollution level and at the New Danube a low faecal pollution level according to the classification scheme of Kirschner et al. (2009; Tables 1 and 2). The measured values were assumed as river source water concentrations in the groundwater simulations for the scenarios (Table 1).

In the main backwater branches of the study area, the faecal contamination decreased with increasing distance from the Danube (from sampling site LSW1 to LSW3, Fig. 3). The observed gradient of faecal contamination correlated with the decreasing connectivity of the sampling site with the Danube (Frick et al. 2020). At the sampling sites LSW 4, 7 and 8 representing sites with little connectivity to the Danube, a high faecal pollution level was found, with 90th percentile values from 1000 to 3200 CFU/100 mL for E. coli, and from 100 to 2500 CFU/100 mL for C. perfringens (spores), respectively (Fig. 3). These elevated concentrations presumably originated from wildlife faeces. A low level of faecal pollution was found at sampling sites LSW 5, 6 and 9, with 90th percentile values ranging from 30 to 130 CFU/100 mL for E. coli, and from 20 to 200 CFU/100 mL for C. perfringens (spores), respectively (Fig. 3).

Observed concentrations of E. coli and C. perfringens (spores) at the observation points in the Danube (DSW 5) and in the backwater (LSW 1–9, Fig. 1) (DSW 5: n = 31, LSW 1: n = 33, LSW 2: n = 33, LSW 3: n = 34, LSW 4: n = 28, LSW 5: n = 31, LSW 6: n = 31, LSW 7: n = 14, LSW 8: n = 23, LSW 9: n = 29). The boxes indicate the 25th and 75th percentile, the whiskers indicate the 10th and 90th percentile, circles indicate values between the 5th and 95th percentile, horizontal lines indicate the median values

The microbiological analysis of groundwater samples in the study area (n = 353) resulted in concentrations of 0 CFU/100 mL in most cases, with prevalence rates of 2.5 and 2.8% for E. coli and C. perfringens (spores), respectively. The measured concentrations reached at maximum 9 CFU/100 mL of E. coli and 16 CFU/100 mL of C. perfringens (spores), respectively.

3.2 Scenarios of increasing floodplain connectivity

A Kruskal Wallis test showed that the simulated diversion of 3 m3/s of New Danube water into the backwater branch during LW already led to a significant deterioration of the microbiological groundwater quality as compared to the reference scenario (χ2(1) = 26.3, p = 2.8 × 10−7, n = 3899, Fig. 4). Higher simulated concentrations of E. coli in groundwater near the drinking water wells PGAW 1, 3, 4 and 5 in comparison with the reference case would even lead to more elevated detection rates at these sites. According to the simulations, the microbiological groundwater quality deteriorates along parts of the main backwater branch, while it improves along other parts of the main backwater branch compared with the reference scenario (Fig. 4). A similar effect was shown for C. perfringens (spores).

Difference between simulated concentrations of E. coli with and without diverting 3 m3/s of New Danube water into the backwater area at low water level (LW) conditions (positive/negative values indicate an increase/decrease in concentrations). Indicated are the concentrations at the bottom of the aquifer after 60 days of simulation time. The same results were obtained for C. perfringens (spores)

When diverting 3 m3/s of Danube water into the backwater branch during LW, the microbiological groundwater quality near wells PGAW 1, 3, 4 and 5 deteriorated significantly more than if diverting New Danube water as shown by a Kruskal Wallis test (χ2(1) = 938.4, p = 4.3 × 10−206, n = 5241, Fig. 5). For all of the above scenarios, positive differences between simulated concentrations of E. coli with and without diverting 3 m3/s were found within the well catchment area of PGAW 1, which would therefore lead to higher detection frequencies in groundwater. Due to the higher flow rates of the main backwater branch in the scenarios than for the reference, parts of the ephemeral side branches filled up with water. Such conditions currently occur only during flood events. During MW + 1, the concentrations of both faecal indicators increased even more than during LW near the main backwater branch (results not shown). The diversion of 20 to 80 m3/s of Danube water at MW likewise led to significantly increased concentrations of faecal indicators as shown by a Kruskal Wallis test in particular in the region near the main backwater branch (χ2(1) = 357.4, p = 1.0 × 10−79, n = 4317, Fig. 6, and, χ2(1) = 543.7, p = 2.8 × 10−120, n = 4668, Fig. 7). The diversion of 80 m3/s of Danube water additionally resulted in elevated concentrations of both faecal indicators near wells PGAW 4 and PGAW 5 (Fig. 7). We tested the plausibility of the model results by comparing the simulated and observed concentrations of E. coli at well PGWA5. According to the simulations, the concentrations of E. coli ranged from 1 × 10−3 to 1 × 10−2 CFU/100 mL at well PGWA 5 during MW + 1 conditions (results not shown). The standard monitoring of E. coli at this well over multiple years showed concentrations in the same range only 3 to 5 times per year, which corresponds with the frequency in which this well is influenced by the Danube. The measured concentrations of E. coli at all other wells during these times were below the limit of detection corresponding with the simulation results.

Representing Fig. 4 but for diverting 3 m3/s of Danube water into the backwater area

Representing Fig. 4 but at mean water level (MW) for diverting 20 m3/s of Danube water into the backwater area

Representing Fig. 4 but at mean water level (MW) for diverting 80 m3/s of Danube water into the backwater area

4 Discussion

4.1 Combining hydrodynamic modelling with data from standard faecal indicator bacteria

The aim of this study was to investigate the effect of diverting river water into an alluvial floodplain area on the microbiological groundwater quality as a resource for drinking water supply. The quality criteria were chosen according to the Austrian regulations for drinking water and groundwater protection (Austrian Drinking Water Ordinance 2001; Water Rights Act 1959). We addressed this question by combining faecal indicator concentrations in surface water at detectable levels with hydrodynamic surface water flow and 3‑D groundwater transport modelling. The starting point of the microbiological water quality assessment was determined by the analysed concentrations of faecal indicators in groundwater during monthly monitoring. Then, concentrations of E. coli and C. perfringens (spores) were simulated for the reference case, which is no diversion of river water, and compared with the diversion scenarios of 3, 20 and 80 m3/s.

The scenarios showed that diverting 3 to 80 m3/s of Danube water or New Danube water into the backwater area leads to significantly increased concentrations of faecal indicators in groundwater (p < 0.05), which would cause a higher detection rate during the standard monitoring. Already a diversion rate of 3 m3/s led to higher water levels and thus to side branches filling with water, which so far only filled during flood events. Measures to divert 20 to 80 m3/s of water into the backwater area would lead to increases in the water level dynamics, would homogenize the water quality and prevent the eutrophication of isolated backwater branches according to previous studies (Gabriel et al. 2014; Weigelhofer et al. 2014). Despite of this, these measures cannot be recommended from the viewpoint of groundwater as a safe drinking water resource, as the deterioration of the microbiological groundwater quality was shown to affect the drinking water well catchments. All investigated scenarios showed significantly increased concentrations of E. coli and C. perfringens (spores) in the range of 10−3 to 102 CFU/100 mL (p < 0.05). Increased concentrations in this range would lead to higher detection frequencies during water quality monitoring programs in the short and medium term.

4.2 Future perspectives—linking modelling with microbial faecal source tracking and QMRA

In order to assess the safety of the drinking water resources concerning the infection protection, quantitative microbial risk assessment (QMRA) methods could be used. Further parameters to determine the origin of faecal contamination (e.g. animals versus humans) could be valuable tools to track long-term changes of the groundwater quality and to evaluate the QMRA models. These include microbial source tracking markers, bacteriophages as alternative sensitive viral indicators to detect faecal contamination, or parameters for analysing the biological stability of groundwater. Automated online techniques are becoming increasingly important to detect short time microbiological contamination as occurring during floods. Near-real time measurement techniques based on biochemical-physical online measurements are promising parameters for complementing chemo-physical online measurements as continuous process control.

5 Conclusion

In this study, we evaluated how an increased connectivity of a backwater branch located in a nature-protected backwater area of the Danube (enabled by diverting Danube water into the system via a weir) affects the microbiological quality of groundwater resources. While the additional discharge of 20 and 80 m3/s of Danube water into the floodplain strongly improved the ecological status according to ecological habitat models, the hydraulic transport simulations showed that this would result in a deterioration of the microbiological quality of groundwater resources. The presented approach based on microbiological analysis of the water resources combined with hydraulic flow and transport modelling is useful to support decision-making.

References

Arnberger, A., Frey-Roos, F., Eder, R., Muralt, G., Nopp-Mayr, U., Tomek, H. and Zohmann, M. (2009): Ecological and social carrying capacities for peri-urban biosphere resources. Man & Biosphere-Programme of the Academy of Science, Austrian Academy of Science, Vienna, Austria 135.

Artz, R.R.E., Townend, J., Brown, K., Towers, W. and Killham, K. (2005): Soil macropores and compaction control the leaching potential of Escherichia coli O157:H7. Environmental Microbiology 7(2), 241–248.

Austrian Drinking Water Ordinance (2001): Verordnung über die Qualität von Wasser für den menschlichen Gebrauch (Trinkwasserverordnung – TWV) BGBl. II Nr. 304/2001 [CELEX-Nr.: 398L0083]. Federal Ministry of Social Affairs, Health, Care and Consumer Protection, Austria.

Derx, J., Blaschke, A.P., Farnleitner, A.H., Pang, L., Bloschl, G. and Schijven, J.F. (2013): Effects of fluctuations in river water level on virus removal by bank filtration and aquifer passage—A scenario analysis. Journal of Contaminant Hydrology 147, 34–44.

Frick, C., Vierheilig, J., Nadiotis-Tsaka, T., Ixenmaier, S., Linke, R., Reischer, G.H., Komma, J., Kirschner, A.K.T., Mach, R.L., Savio, D., Seidl, D., Blaschke, A.P., Sommer, R., Derx, J. and Farnleitner, A.H. (2020): Elucidating fecal pollution patterns in alluvial water resources by linking standard fecal indicator bacteria to river connectivity and genetic microbial source tracking. Water Research, 116132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2020.116132.

Frühauf, J. and Sabathy, E. (2006): Untersuchung an Schilf- und Wasservögeln in der Unteren Lobau, Teil I: Bestände und Habitat. Wissenschaftliche Reihe 23, 1–68.

Gabriel, H., Blaschke, A.P., Taschke, R. and Mayr, E. (2014): Water connection (New) Danube—Lower Lobau (Nationalpark Donauauen), Water Quantity Report for Surface Water, Municipial Department MA45—Vienna Waters, Vienna, Austria.

Gelhar, L.W., Welty, C. and Rehfeldt, K.R. (1992): A Critical-Review of Data on Field-Scale Dispersion in Aquifers. Water Resources Research 28(7), 1955–1974.

van Genuchten, M.T. (1980): A Closed-Form Equation for Predicting the Hydraulic Conductivity of Unsaturated Soils. Soil Science Society of America Journal 44(5), 892–898.

ISO 14189 (2013): International Organisation for Standardisation ISO 14189 Water quality—Enumeration of Clostridium perfringens—Method using membrane filtration, Geneva, Switzerland.

ISO 16649‑2 (2001): International Organisation for Standardisation ISO 16649‑2 Microbiology of food and animal feeding stuffs—Horizontal method for the enumeration of beta-glucuronidase-positive Escherichia coli—Part 2: Colony-count technique at 44 degrees C using 5‑bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl beta-D-glucuronide, Geneva, Switzerland.

ISO 9308‑3 (1998): International Organisation for Standardisation ISO 9308‑3 Water quality—Detection and enumeration of Escherichia coli and coliform bacteria—Part 3: Miniaturized method (Most Probable Number) for the detection and enumeration of E. coli in surface and waste water, Geneva, Switzerland.

Kinzelbach, W. (1987): Numerische Methoden zur Modellierung des Transports von Schadstoffen im Grundwasser. Oldenbourg, München. ISBN: 9783486263473.

Kirschner, A.K.T., Kavka, G.G., Velimirov, B., Mach, R.L., Sommer, R. and Farnleitner, A.H. (2009): Microbiological water quality along the Danube River: Integrating data from two whole-river surveys and a transnational monitoring network. Water Research 43(15), 3673–3684.

KWD (2010): The characteristic water levels of the Austrian Danube. Edited by the viadonau, as of December 31st, 2010, viadonau, Vienna, Austria.

de Marsily, G. (1986): Quantitative Hydrogeology, Academic Press, New York.

Nasser, A.M., Tchorch, Y. and Fattal, B. (1993): Comparative Survival of E. coli, F+Bacteriophages, HAV and Poliovirus 1 in Wastewater and Groundwater. Water Science and Technology 27(3–4), 401–407.

Pang, L. (2009): Microbial removal rates in subsurface media estimated from published studies of field experiments and large intact soil cores. Journal of Environmental Quality 38(4), 1531–1559.

Parz-Gollner, R. (2006): Zur Situation der Kormoranschlafplätze im Nationalpark Donau-Auen (NÖ) – Auswirkungen der Uferrückbauten im Bereich des Schlafplatzes Turnhaufen. University of Applied Science, Vienna, Austria.

Schaap, M.G., Leij, F.J. and van Genuchten, M.T. (2001): Rosetta: a computer program for estimating soil hydraulic parameters with hierarchical pedotransfer functions. Journal of Hydrology 251(3), 163–176.

Smith, M.S., Thomas, G.W., White, R.E. and Ritonga, D. (1985): Transport of Escherichia coli through intact and disturbed soil columns. Journal of Environmental Quality 14(1), 87–91.

Voss, C.I. and Provost, A.M. (2010): SUTRA—a model for saturated—unsaturated variable-density ground water flow with solute or energy transport. Technical Report Water-Resources Investigations Report 02-4231, (Reston, Virginia), Version of September 22, 2010.

Water Rights Act (1959): Wasserrechtsgesetz BGBl. Nr. 215/1959 idgF. Federal Ministry of Agriculture, Regions and Tourism, Austria.

Weigelhofer, G., Preiner, S. and Hein, T. (2014): Water quality surface water (Lobau) Water connection (New) Danube - Lower Lobau (Nationalpart Donauauen) on behalf of the MA 45 water authority, Vienna, Austria, 84 pages.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) as part of the Vienna Doctoral Program on Water Resource Systems (W1219-N22), and the research project Groundwater Resource Systems Vienna as part of the (New) Danube—Lower Lobau Network Project (LE07-13) in cooperation with Vienna Water. This is a joint investigation of the Interuniversity Cooperation Centre for Water & Health (www.waterandhealth.at).

Funding

Open access funding provided by TU Wien (TUW).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Derx, J., Komma, J., Reiner, P. et al. Using hydrodynamic and hydraulic modelling to study microbiological water quality issues at a backwater area of the Danube to support decision-making. Österr Wasser- und Abfallw 73, 482–489 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00506-021-00797-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00506-021-00797-7

Keywords

- Hydraulic transport model

- Faecal indicators

- Alluvial floodplains

- Microbiological water quality

- Drinking water resources