Abstract

We created a fault model with a Tohoku-type earthquake fault zone having a random slip distribution and performed stochastic tsunami hazard analysis using a logic tree. When the stochastic tsunami hazard analysis results and the Tohoku earthquake observation results were compared, the observation results of a GPS wave gauge off the southern Iwate coast indicated a return period equivalent to approximately 1,709 years (0.50 fractile), and the observation results of a GPS wave gauge off the shore of Fukushima Prefecture indicated a return period of 600 years (0.50 fractile). Analysis of the influence of the number of slip distribution patterns on the results of the stochastic tsunami hazard analysis showed that the number of slip distribution patterns considered greatly influenced the results of the hazard analysis for a relatively large wave height. When the 90 % confidence interval and coefficient of variation of tsunami wave height were defined as an index for projecting the uncertainty of tsunami wave height, the 90 % confidence interval was typically high in locations where the wave height of each fractile point was high. At a location offshore of the Boso Peninsula of Chiba Prefecture where the coefficient of variation reached the maximum, it was confirmed that variations in maximum wave height due to differences in slip distribution of the fault zone contributed to the coefficient of variation being large.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

In earthquake-induced tsunami hazard analysis, it is extremely important to ascertain the effect of earthquake source parameters on the initial displaced water height of tsunamis. Numerous studies on this influence have been conducted (e.g., Hwang and Divoky 1970; Ward 1982; Ng et al. 1991; Pelayo and Wiens 1992; Whitmore 1993; Geist and Yoshioka 1996; Geist 1999; Song et al. 2005). Based on observations of the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, Song et al. (2005) concluded that slip function is an important factor that governs tsunami intensity and that the fracture rate of the earth’s crust determines the spatial pattern of a tsunami. It is now well known that the amount of slip of a rupturing fault strongly affects tsunami wave height, as numerous past studies have indicated.

On the other hand, Freund and Barnett (1976) pointed out that tsunami wave height is underestimated more when tsunami calculations are performed with uniform slip distributions than with heterogeneous slip distributions, but studies on the effect of planar nonuniformity of fault slip on tsunami wave height are limited (e.g., Geist and Dmowska 1999; Geist 2002; McCloskey et al. 2007, 2008; Løvholt et al. 2012). Geist (2002) calculated tsunami wave height uncertainty for the Pacific coastline of Mexico by fixing the moment magnitude at 8.0 and using a trench fault with 100 cases of random slip. He ascertained that random slip distribution of a trench fault significantly affected the localized coastal wave height and that coastal wave height varied three-fold on average and six-fold at maximum. McCloskey et al. (2007, 2008) examined coastal wave height uncertainty for the Sumatra coast using approximately 100 cases of initial displaced water height values calculated from a trench fault with a random slip distribution that was artificially generated in the same manner. They also confirmed that nonuniformity of slip distribution greatly influenced coastal wave height. Løvholt et al. (2012) quantitatively studied the effect of 500 cases of artificially generated random trench slip distributions on tsunami runup height. They concluded that a hydrostatic pressure model produces artificially high uncertainty and that a nonhydrostatic pressure model produces a decrease in uncertainty.

However, even though these studies describe the effect of planar nonuniformity of slip on a fault on tsunami wave height or tsunami runup height, they do not describe its influence on stochastic tsunami hazard analysis. Thus, we focused on the influence of nonuniformity of slip distribution on a fault on the results of a stochastic tsunami hazard analysis. Various methods of the stochastic tsunami hazard analysis have been proposed by past many studies (e.g., Lin and Tung 1982; Rikitake and Aida 1988; Ward 2002; Geist 2005; Thio 2010; Yong et al. 2013). In this study, we adopted a method of stochastic tsunami hazard analysis using a logic tree (Annaka et al. 2007). Specifically, using a random source parameter model that determined the probability of slip distributions including asperity in a fault zone, we produced multiple giant faults with hypothetical slip distributions for a Tohoku-type fault zone. Then, by treating these multiple giant faults as branches of a logic tree, we treated heterogeneous slip on the fault as epistemic uncertainty. We also examined how the results of the tsunami hazard analysis changed when the number of branches of the logic tree was varied. We used only five patterns of generated random slip distribution, but it appears that they have a large effect on the results of stochastic tsunami hazard analysis when using a logic tree. In this study, we also discuss the regional uncertainty of stochastically assessed tsunami wave height.

2 Assessment of slip distribution on a fault using a random source model

In this study, we used the correlated random source parameter (CRSP) model (Liu et al. 2006) to generate random slip distributions on a fault plane. The CRSP model is a recently proposed kinematic fault model that smoothly varies slip distributions on fault planes. In this model, a two-dimensional distribution of parameters such as slip, slip angle, rupture propagation rate, and rupture rise time on a fault plane can be estimated based on a probability density function obtained by statistically processing slip distributions estimated from past earthquake records. In this study, we used only the two-dimensional slip distributions that were generated using the CRSP model. The procedure for creating a hypocenter model using this technique is as follows.

First, a completely random two-dimensional Gaussian distribution is generated. Then, the generated random two-dimensional Gaussian distribution is transformed to wavenumber space by a two-dimensional Fourier transform and multiplied by the following filter (Mai and Beroza 2002).

Here, k x is the wavenumber of fault strike direction, k y is the wavenumber of fault dip direction, ν is the fractile dimension, C L is the correlation length of the fault strike direction, and C W is the correlation length of the fault dip direction. We set a ν value to 4.0, which was determined by Liu et al. (2006). C L and C W are calculated from the following equations, where Mw is the moment magnitude of the earthquake fault.

Next, by Fourier inverse transformation of the two-dimensional distribution that has been multiplied by the filter expressed in Eq. (1), a random Gaussian distribution in which the amplitude in wavenumber space attenuates according to \( k^{ - \nu /2} \) is obtained. Finally, using the NORTA method (Cairo and Neilson 1997), it is transformed to the following truncated Cauchy distribution in which fault slip distribution follows from the obtained random Gaussian distribution. This probability distribution is based on studies in which past earthquake inversion analyses were statistically processed (Lavallée and Archuleta 2003, 2005; Lavallée et al. 2006).

Here, C is the normalized probability density function, D o is the Cauchy distribution location parameter, κ is the Cauchy distribution scale parameter, and D max is the maximum slip of fault. κ is a coefficient that is set such that the average value of the slip distribution is equal to the average slip across the fault. The average slip across the fault was taken as D ave, and the following values were used for D o and D max;

The coefficient of 2.8 in Eq. (5) uses the ratio of maximum slip and average slip in the shallow part of the 2011 Tohoku earthquake as a reference. In particular, using the results of Yoshida et al. (2011), who studied the rupture process of the Tohoku earthquake using the waveform inversion technique with long-period seismic motion data, Ishii et al. (2013) concluded that the average slip of the shallow part was 16.7 m and that the maximum slip was 46.9 m. Based on these results, we set the ratio of maximum slip to average slip in the truncated Cauchy distribution at 2.8. The coefficient of 0.5 in Eq. (6) is the coefficient of Liu et al. (2006), without modification.

Ishii et al. (2013) focused on a prominent feature of the Tohoku earthquake (i.e., the slip in the shallow part was larger than the slip in the deep part) and proposed a technique by which the average slip of each part is calculated by using the area and modulus of rigidity of each part after the fault is divided into a deep and shallow part. A value of approximately 3.0, derived from analysis of the Tohoku earthquake, has been used as the ratio of average slip of the deep part to that of the shallow part.

In this study, we modeled the hypocenter of the rupture zone of the Tohoku earthquake using the technique of Liu et al. (2006) for generating random slip distributions and the technique of Ishii et al. (2013) for calculating average slip in the shallow and deep parts. A schematic diagram of the modeling is shown in Fig. 1. First, a giant fault was divided into a shallow and deep part, and the average slip of each part was calculated using the technique of Ishii et al. (2013). Because the value of average slip varies with the area of each part according to the scaling law, the depth of the boundary between the shallow and deep parts of the fault model in this study was uniformly set to 15 km so as to align it with the area of the shallow (27,000 km2) and deep part (73,000 km2) set by Ishii et al. (2013). If the average slip of each part is determined, it is possible to determine the maximum slip of each part uniquely using Eq. (5). Furthermore, the ratio of average slip and maximum slip of the deep part was assumed to be the same as the ratio of average slip and maximum slip of the shallow part. Specifically, we consider it necessary to concretely determine the ratio of average slip and maximum slip of the shallow part from observation results, but because we could not obtain concrete data, we assumed the ratio of average slip to maximum slip to be the same in both the shallow and deep parts. Next, based on the average slip and maximum slip of each part, the technique of Liu et al. (2006) was applied to both the deep and shallow parts to generate a random slip distribution for each part. Table 1 shows the average slip in the deep and shallow parts and the maximum slip across the entire fault zone (maximum slip of shallow part) calculated in this study and by Yoshida et al. (2011). The results in this study, in which slip was artificially generated using the CRSP model, are slightly higher but express the general trend of numeric values quite well.

Schematic diagram of modeling a Tohoku-type earthquake fault. When the fault was thought of in terms of a deep part (73,000 km2) and shallow part (27,000 km2), the depth of the fault between areas was approximately 15 km. The ratio of average slip of the deep part to that of the shallow part was taken as 3.0 (Ishii et al. 2013). The ratio of maximum slip to average slip in the shallow part was taken as 2.8 (Yoshida et al. 2011). The ratio of maximum slip to average slip in the deep part was assumed to be 2.8, similar to the shallow part

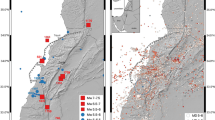

For the earthquake fault parameters, we used the longitude, latitude, length, width, upper depth, and strike and dip angle of the fault endpoint of a Tohoku-type earthquake fault published by Fujiwara et al. (2013) (Table 2). Figure 2 shows five patterns of a hypocenter model having different two-dimensional locations of slip distribution generated by the above technique. The figure shows that the large slip region of the shallow part, like that actually produced by the Tohoku earthquake, can be expressed well. The asperity area ratio in the fault for these five cases is shown in Table 3. Somerville et al. (1999) defined asperity as the region having a slip that is at least 1.5 times greater than the average slip across a fault, and, based on analyzing the area of asperities of 15 past earthquakes, demonstrated that asperity accounts for 22 % (average), 10 % (minimum), and 40 % (maximum) of the area of the entire fault. When the fault asperity of the five cases generated in this study is calculated based on the above definition, the area ratio of asperity to total fault area (100,000 km2) is in the range of 12.5–18.1 %, which agrees relatively well with the results of Somerville et al. (1999); we believe it can appropriately express the heterogeneous slip distribution characteristics of actual fault slip.

Modeled Tohoku-type earthquake faults having different slip distributions: a asperity at the northern edge of the fault, b asperity between the northern edge and center of the fault, c asperity at the center of the fault, d asperity between the southern edge and center of the fault, and e asperity at the southern edge of the fault. Red stars and yellow stars indicate the locations of the Fukushima Prefecture offshore GPS wave gauge and the south Iwate offshore GPS wave gauge, respectively, which were set up by MLIT

3 Stochastic tsunami hazard analysis

3.1 Numerical tsunami simulation method

Based on the Tohoku-type earthquake fault model generated in Sect. 2, we calculated tsunami wave height at each point as follows. First, the points of a 10-km mesh encompassing a Tohoku-type earthquake fault zone (500 km × 200 km) were generated; then, using the fault parameters in Table 2 and the fault slip artificially generated by the CRSP model as input values, the initial displaced water height was calculated at those points using the formula of Okada (1985). Here, the slip angle was assumed to be a uniform 90°. Using the calculated initial displaced water height as input values, time integration was performed with a time interval of 0.9 s and a grid spacing of 15 s (approximately 450 m) at the longitude/latitude origin by a nonlinear long-wave equation using the TUNAMI program (Tohoku University’s Numerical Analysis Model for Investigation of Far-field Tsunamis, IUGG/IOC TIME Project 1997).

3.2 Logic tree construction

Next, to stochastically analyze the tsunami hazard, we constructed a logic tree with five branch levels (range of moment magnitude, position of asperity, earthquake return period, log normal standard deviation expressed as aleatory uncertainty, and truncated uncertainty) based on the technique of Annaka et al. (2007) (Fig. 3).

Logic tree for stochastic analysis constructed for the Tohoku-type earthquake fault. Branches are range of moment magnitude, position of asperity, average recurrence interval, log normal standard deviation (logarithm of Aida’s kappa), and truncated range of the deviation. The number appended to each branch indicates the weight of that branch

Here, we would like to clarify the definitions and handling methods regarding aleatory uncertainty and epistemic uncertainty in this study. Annaka et al. (2007) explain that aleatory uncertainty is due to the random nature of earthquake occurrence and its effects. Its nature can be determined from the variation in the ratios of observed to numerically calculated tsunami heights for historical tsunami sources (Aida 1978) in their model, which is named “Aida’s kappa (κ)”. They also stated that epistemic uncertainty is due to incomplete knowledge and data about the earthquake process. Uncertainties in various model parameters and various alternatives are treated as epistemic uncertainty using the logic-tree approach.

Aida’s kappa, corresponding to aleatory uncertainty in this study, is determined from a numerical simulation for the optimal fault models of 11 tsunamigenic earthquakes with many historical run-up data (Table 4). However, the uncertainty that can be captured by this calculation only represents the difference between tsunami observation data due to an earthquake that occurred in the past and the tsunami value estimated from the earthquake model using numerical simulation. For the reason stated above, the Japan Society of Civil Engineers (2011) mentioned that parameters, which could vary even though the earthquakes occurred in the same place, should also be considered as “variability due to changing of fault models” (aleatory variability) or “uncertainty of fault models” (epistemic uncertainty). Therefore, in this study, we considered earthquake source models having different slip distributions that have not occurred in the past, as described in the second chapter, the moment magnitude of the earthquakes, and the recurrence interval as epistemic uncertainty. In addition, we treated variability of Aida’s kappa and its truncation as epistemic uncertainty.

For the moment magnitude (M w), three cases of M w 8.9, 9.0, and 9.1 were considered. Variations in moment magnitude are obtained by multiplying the slip across the fault by a coefficient calculated from seismic moment M o (N*m) = μDS, where μ is the fault rigidity (N/m2), S is the fault area (m2), and D is the average displacement (m) across the fault.

For the position of the asperity, we initially generated many two-dimensional distributions of slip on the fault using the CRSP model. From these, we subjectively selected just five patterns of slip distribution such that the position of asperity was dispersed throughout the entire fault. Variations in the tsunami water level accompanying the variations in slip distribution in the strike direction of the fault are greater than the variations in the tsunami water level accompanying the variations in slip distribution in the dip direction (Geist and Dmowska 1999). Therefore, we considered fault patterns in which the variations in slip distribution in the strike direction were expressed more distinctly than were the variations in the slip distribution in the dip direction of the fault. In this study, we dealt with five, three, and one pattern of slip distributions, but we will confirm the large influence on the hazard curve, as will be discussed later.

For the return period of the Tohoku-type earthquake, we used the value of 600 years employed by Fujiwara et al. (2013). In their analysis, a model of the average return period for the Tohoku earthquake was treated as the BPT distribution. In this study, we decided on a deviation of the BPT distribution as 0.3 and set an upper limit and lower limit confidence interval based on its error.

For the log-normal standard deviation (aleatory uncertainty) and truncated uncertainty, we used the values of Annaka et al. (2007), which were determined from a numerical simulation for the optimal fault models of 11 tsunamigenic earthquakes with many historical run-up data (Table 4).

The number appended to each branch of the logic tree in Fig. 3 indicates the weight of that branch. For the branches related to the range of moment magnitude and position of the asperity, the values were equally divided weights. For the weights for each branch of the recurrence interval, we set the basis value as 0.5 and both end values as 0.25 because we set the branch by considering the confidence interval. Finally, regarding the weights for the branches of the standard deviation of the log-normal distribution and truncation of the log-normal distribution, we adapted the weighting values used in the study of Annaka et al. (2007); these values were used when they used a variable fault model in their study.

3.3 Hazard curves

Based on the constructed logic tree and the simulated tsunami wave heights, we created hazard curves (Fig. 4a). Each curve corresponds to a branch of epistemic uncertainty (logic tree) with the aleatory uncertainty for each outcome shown in Fig. 4a. The method by which each hazard curve is generated is as follows. First, we can derive a probability density function of a log-normal distribution, expressed as Eq. (7), when we set a maximum tsunami height value, calculated from the tsunami numerical simulation, using the condition of each branch of the logic tree as a median value (μ) and set a logarithm of Aida’s kappa as the log-normal standard deviation (σ):

a The 360 hazard curves corresponding to all branches of the logic tree, b relationship between annual probability of exceedance and cumulative branch weight at a certain wave height, and c examples of statistically processed hazard curves (0.05 fractile curve, 0.50 fractile curve, 0.95 fractile curve, and simple average curve)

Second, we can obtain a tsunami hazard curve by converting the probability density function into an exceedance probability distribution on the assumption of an ergodic hypothesis. The ergodic hypothesis is a statistical assumption that spatial variability is equal to temporal variability. Therefore, if we use the log-normal distribution that indicated spatial variability, we can obtain a tsunami hazard curve that shows the relationship between tsunami height and the annual probability of exceedance.

The hazard curves are drawn to correspond to one specific location. Here, for example, the hazard curves at the installation site (39.259°N, 142.097°E) of the south Iwate offshore GPS wave gauge set up by the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism (MLIT) in April 2007 are shown. The same number of hazard curves as the number of branches of the logic tree (3 × 5 × 3 × 4 × 2 = 360) was created.

From these 360 hazard curves, statistical processing was performed in consideration of branch weight. Annual probability of exceedance at a certain tsunami wave height and cumulative branch weight are shown in Fig. 4b. These were calculated in the same manner as the tsunami wave height from 0.0 to 0.1 m, and annual probability of exceedance was determined at the points of 95, 50, and 5 % cumulative weight. From this, the relationship between tsunami wave height and annual probability of exceedance was re-drawn, resulting in the 95, 50, and 5 % fractile curves shown in Fig. 4c. The fractile curves simultaneously include epistemic uncertainty and aleatory uncertainty in earthquake occurrence and tsunami propagation. The analysis of this hazard curve, which includes the various types of uncertainty, enables a stochastic interpretation of a tsunami hazard. Additionally, a curve produced by simply averaging the annual probability of exceedance without considering branch weight was also generated as a simple average curve. We note that the tsunami hazard curves presented in this study are actually the conditional hazard exceedance curves because only 3.11 Tohoku-type earthquake events are included in the logic tree. However, we can say that we conducted stochastic tsunami hazard analysis in terms of considering the variability of the moment magnitude, position of asperity, and recurrence interval of the target earthquake. In addition, there is a possibility that other parameters such as the log-normal standard deviation or weights based on expert judgment strongly influence the shape of the hazard curves (e.g., Annaka et al. 2007; Iwabuchi et al. 2014). However, we would like to note that we focused on how the hazard curves change in response to the different positions of asperity in the logic tree, on the premise that parameters such as the log-normal standard deviation and weights based on expert judgment are fixed.

3.4 Comparison with Tohoku earthquake observation results and a past study

In this section, we compare the results of the stochastic tsunami hazard analysis performed in Sect. 3.1 with the observation results of the Tohoku earthquake that occurred in 2011 and a past study performed by Sakai et al. (2006). The measurement data of the south Iwate offshore GPS wave gauge and the Fukushima Prefecture offshore GPS wave gauge set up by MLIT and analyzed by Port and Airport Research Institute (PARI) were used as the Tohoku earthquake observation data (Kawai et al. 2013).

3.4.1 Comparison with the south Iwate offshore GPS wave gauge observation results

Figure 5a shows the waveform observed during the Tohoku earthquake, measured by the south Iwate offshore GPS wave gauge. The position of the south Iwate offshore wave gauge is indicated by the yellow star in Fig. 2a. According to information published by MLIT, the maximum tsunami wave height at the south Iwate offshore GPS wave gauge was 6.7 m. The results of stochastic tsunami hazard analysis at the same location are shown in Fig. 4c. In addition, the relationship between the return period and fractile point at the maximum wave height of 6.7 m observed during the Tohoku earthquake is indicated by the red line in Fig. 6. The results show that the range of the return period is approximately 1,780 years at the 0.50 fractile wave height and 450 years at the 0.95 fractile wave height. Furthermore, the return period at the 0.50 fractile wave height is 1,709 years. In a report by Fujiwara et al. (2013), the return period of the 2011 Tohoku earthquake was estimated at approximately 600 years, but in the results of our analysis, approximately 600 years is equivalent to a fractile from 0.81 to 0.91, which is a relatively high fractile point.

Waveform of the Tohoku earthquake tsunami: a measured at the south Iwate offshore GPS wave gauge (39.259°N, 142.097°E)—the maximum wave height recorded was 6.7 m—and b measured at the Fukushima Prefecture offshore GPS wave gauge (36.971°N, 141.186°E)—the maximum wave height recorded was 2.6 m (Kawai et al. 2013)

Relationship between the return period and fractile point of a probable wave with a height of 6.7 m at the south Iwate offshore GPS wave gauge (red line) and relationship between the return period and fractile point of a probable wave with a height of 2.6 m at the Fukushima Prefecture offshore GPS wave gauge (blue line)

3.4.2 Comparison with the Fukushima Prefecture offshore GPS wave gauge observation results

Figure 5b shows the waveform observed during the Tohoku earthquake, measured by the Fukushima Prefecture offshore GPS wave gauge. The position of the Fukushima Prefecture offshore wave gauge is indicated by the red star in Fig. 2a. According to information published by MLIT, the maximum tsunami wave height at the Fukushima Prefecture offshore GPS wave gauge was 2.6 m. The results of stochastic tsunami hazard analysis at the same location are shown in Fig. 7. In addition, the relationship between the return period and fractile point at the maximum wave height of 2.6 m observed during the Tohoku earthquake is indicated by the blue line in Fig. 6. The results show that the range of the return period is 600 years at the 0.50 fractile wave height and 450 years at the 0.95 fractile wave height. The return period at the 0.50 fractile wave height is 600 years. According to our analysis, the return period of the Tohoku earthquake of approximately 600 years is equivalent to a fractile between 0.35 and 0.75; this is a relatively wide fractile range.

3.4.3 Comparison with a past study

Sakai et al. (2006) also conducted probabilistic tsunami hazard analysis using the logic-tree approach, targeting the coast of Fukushima Prefecture. Before comparing our research with their work, it is important to note that one of the fundamental differences between the two studies is that our research considers only the Tohoku earthquake type fault (M w 8.9–9.1), while their research considered nine earthquake faults (M w 7.7–8.6) along the Japan trench for the near-field tsunami. In addition, the contents and weights of the branches in the logic tree differ between the two studies. Thus, although there are some differences in the conditions of the studies, we discuss the results of the analyses in the following.

In the long-term averaged hazard curve of Sakai et al. (2006), wave heights with a return period of 1,000 years had a range of about 3.5 m (0.05 fractile wave) to about 5.6 m (0.95 fractile wave). However, in our study, wave heights with a similar return period had a range of about 4.0 m (0.05 fractile wave) to about 17.3 m (0.95 fractile wave). It is indicated that both the calculated stochastic tsunami height and its range in our analysis are larger than in their analysis, which is mainly because the moment magnitude of the assumed earthquake fault in our analysis is larger. Furthermore, the difference of the 0.05 fractile wave between the analyses is about 0.5 m, while the difference of the 0.95 fractile wave is about 13.3 m. We can also understand from the results that the difference in tsunami height between the analyses has a larger value as the fractile point is large.

3.5 Influence of the number of random slip distribution patterns on the results of hazard analysis

In this section, we examine the influence of the number of random slip distribution patterns in a fault zone on the results of stochastic tsunami hazard analysis. In the logic tree, variations in slip distribution in the fault zone are handled by a separate branch as epistemic uncertainty. Thus, we examined the effect of the number of slip distribution patterns in the fault zone on the stochastic tsunami hazard results by comparing the analysis results when using five slip distribution patterns (standard case), three patterns, and one pattern. For the case of three patterns, we considered the cases where the slip distribution was at the northernmost part, in the center, and at the southernmost part of the hypothetical fault. For the one pattern case, we only considered the case where the slip distribution was in the center. Since the number of branches of the logic tree changes if the number of slip distribution patterns is changed, the number of hazard curves also changes. When there are three slip distribution patterns, the number of branches is 216 (3 × 3 × 3 × 4 × 2), and when there is one, the number of branches is 72 (3 × 1 × 3 × 4 × 2).

Figure 8 shows the hazard curves at the site of the south Iwate offshore GPS wave gauge for the cases of three slip distribution patterns and one slip distribution pattern. Figure 9 shows the relationship between the return period and fractile at wave heights of 10 and 2.0 m in addition to the maximum wave height of 6.7 m measured during the Tohoku earthquake. These figures show that although there is almost no influence of the number of slip distribution patterns on the results of the hazard analysis in the case of a relatively small wave height (2.0 m), when the wave height is relatively large (6.7, 10 m), the number of slip distribution patterns greatly influences the results of the hazard analysis. In the case of the 10-m wave height, when there is only one slip distribution pattern, the return period at each fractile point provides the largest estimate (low annual probability of exceedance), whereas in the cases of three and five slip distribution patterns, the return period at each fractile point tends to provide an estimate smaller than that in the case of only one pattern (high annual probability of exceedance). In the case of the 6.7 m wave height, no particular trend is seen, but the variability in the estimated return period becomes relatively large compared to when the wave height is 2.0 m. Based on the approximate wave heights, we speculate that there is a great difference in how the number of slip distribution patterns influences the results of the hazard analysis depending on the hypothesized wave source.

Figure 10 shows the tsunami wave height frequency distribution taking into consideration the uncertainty of a 1,000-year return period at the same location. In the cases of the five and three slip distributions, the standard deviation and coefficient of variation are about the same, but when there is only one slip distribution, the frequency of wave heights 10 m and above becomes extremely small. Accordingly, the standard deviation becomes smaller and the coefficient of variation decreases. This is because, in the cases of the five and three slip distributions, a high tsunami wave height was calculated at the south Iwate offshore GPS wave gauge because a large amount of slip was present in the northern portion of the fault, but in the case of only one slip distribution, a high tsunami wave height was not observed at the south Iwate offshore GPS wave gauge because a large amount of slip was present only in the center of the fault.

Tsunami wave height frequency distribution when considering the uncertainty of a 1,000-year return period at the location of the south Iwate offshore GPS wave gauge: a the number of slip distributions is five, b the number of slip distributions is three, and c the number of slip distributions is one. Here, N is the number of tsunami wave heights for which uncertainty is considered, μ is the average, σ is the standard deviation, c.o.v. is the coefficient of variation, min is the minimum value, and max is the maximum value

3.6 Quantitative assessment of uncertainty of tsunami wave height

In this section, we discuss the uncertainty of tsunami wave height in each region of the Tohoku earthquake using the results of stochastic tsunami hazard analysis and the logic tree of Fig. 3.

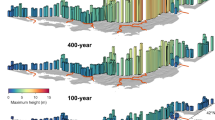

3.6.1 Uncertainty of tsunami wave height in the Tohoku offshore region

Considering the results of stochastic tsunami hazard analysis at the south Iwate offshore GPS wave gauge (Fig. 4), when we consider the tsunami wave height of a certain annual probability of exceedance, we see that various values can be obtained depending on the fractile point. Figure 11a shows the tsunami wave heights at the 5 % fractile point of a 1,000-year return period at a depth of 50 m underwater, offshore from the Tohoku coast, and Fig. 11b shows the tsunami wave heights at the 95 % fractile point at the same locations. For the 5 % fractile wave height, a relatively high wave height from 5.0 m to less than 10 m was calculated primarily offshore from Miyagi Prefecture and Fukushima Prefecture. On the other hand, for the 95 % fractile wave height, a high wave height from 20.0 m to less than 40.0 m was calculated in the coastal regions of the Iwate and Miyagi Prefectures. If we limit the wave height to 5.0 m and above, the offshore area from southern Aomori Prefecture in the north to southern Ibaraki Prefecture in the south was analyzed. In this study, as an index of uncertainty, we defined the wave height equivalent in the range from the 5 % fractile point to the 95 % fractile point (a value obtained by subtracting the 5 % fractile wave height from the 95 % fractile wave height) as the 90 % confidence interval of the tsunami wave height. Figure 11c shows the 90 % confidence interval of tsunami wave height of a 1,000-year return period at the same locations. The figure indicates that, in general, at locations where wave height at each fractile point is high, the 90 % confidence interval is simultaneously high. In particular, a large range in wave height, from 30.0 m to less than 40.0 m, is seen offshore from Iwate Prefecture and at offshore parts in the vicinity of the Oshika Peninsula of Miyagi Prefecture. In the offshore area of Tohoku as a whole, it ranges from a minimum of 0.6 m to a maximum of 36.5 m.

As another index of uncertainty, we defined the coefficient of variation obtained from the standard deviation and average of various tsunami wave heights obtained while focusing on a certain annual probability of exceedance. Figure 11d shows the coefficient of variation of tsunami wave height of a 1,000-year return period. Some very interesting observations can be made from this figure. First, there were multiple locations offshore of the Boso Peninsula of Chiba Prefecture that exhibited high coefficient of variation values, from 0.91 to less than 1.10. When this is considered in combination with Fig. 11a, b, and when we compare the region offshore of the Boso Peninsula of Chiba Prefecture with other regions off the Tohoku coast, the uncertainty of the hypothesized wave height is large, although small wave heights were predicted on average, and there is a high probability of incursion of a wave height divergent from the average wave height. Table 5a shows stochastically processed wave heights at the location at which the maximum coefficient of variation was recorded offshore from the Boso Peninsula of Chiba Prefecture and the maximum wave height of each tsunami calculation. Figure 12a shows the tsunami wave height frequency distribution when considering the uncertainty at the same location. The maximum wave height data calculated directly from the tsunami simulation of Table 5a show a large difference between the maximum wave height when the position of the asperity is placed at the southernmost edge of the fault zone (4.3 m for the case of M w 9.0) and when the position of asperity is placed at the northernmost edge of the fault zone (1.0 m for the case of M w 9.0); we believe this is the cause for the increase in the coefficient of variation. Figure 12a shows a frequency distribution with a relatively wide range at higher wave heights, up to a maximum of 6.8 m with an average of 1.3 m. The second interesting fact is that the point where the coefficient of variation reached a minimum was a point offshore of the Fukushima Prefecture coast. Similarly, Table 5b shows the data at the same location, and Fig. 12b shows the tsunami wave height frequency distribution when considering the uncertainty at the same location. The wave height data for the case of Mw 9.0 calculated directly from the tsunami simulation of Table 5b shows that the wave height was highest when the position of the asperity was placed at the southernmost edge of the fault zone; however, relatively high tsunami wave heights were recorded in all cases. The wave height frequency distribution in Fig. 12b is distributed relatively widely, from a minimum of 4.5 m to a maximum of 18.9 m, but the average wave height was at 10.5 m and the coefficient of variation had the minimum value.

Frequency distribution of tsunami wave height when considering uncertainty at locations where the coefficient of variation reached a the maximum of 1.08 and b the minimum of 0.33. The total number of calculated tsunami wave heights is 360. Here, μ is the average, σ is the standard deviation, c.o.v. is the coefficient of variation, min is the minimum value, and max is the maximum value

3.6.2 Uncertainty of tsunami wave height at the ria coastline of the Tohoku region

Finally, we look at the results for the ria coastline of Iwate Prefecture. Figure 13a shows 0.05 fractile wave height, Fig. 13b shows 0.95 fractile wave height, Fig. 13c shows 90 % confidence interval wave height, and Fig. 13d shows the coefficient of variation of a 1,000-year return period at a depth of 50 m underwater offshore of the ria coastline of Iwate Prefecture. No noticeable trend is seen for the 0.05 fractile wave height, but the values of the 0.95 fractile wave height, 90 % confidence interval, and coefficient of variation show that the values tend to be higher offshore from the peninsular tips of the ria coastline and lower in the closed-off sections of bays. Table 6a shows the data at the location of the maximum coefficient of variation offshore from the tip of a peninsula of the ria coastline, and Table 6b shows the location of the minimum coefficient of variation in a closed-off section of the bay shown in the yellow boxes in Fig. 13. Figure 14 shows the tsunami wave height frequency distribution when considering the uncertainty at the same locations. These data show that, in the vicinity of the peninsular tip of the ria coastline, the standard deviation is larger and the average is smaller than that in the vicinity of the closed-off section of the bay; however, in the vicinity of the closed-off section of the bay, the standard deviation is smaller and the average is larger, and this determines the magnitude of the coefficient of variation. In the vicinity of the peninsular tip of the ria coastline, there is a trend of tsunami waves with high to low wave heights due to the difference in slip distribution within the fault observed widely, and the uncertainty of the tsunami wave height is large. However, in the closed-off section of the bay, the average tsunami wave height is larger than that near the peninsular tip because of effects of the submarine topography in the vicinity, but the range of the obtained wave height is small, i.e., the uncertainty of the tsunami wave height is small. These results clearly demonstrate the influence of topographical effects specific to ria coastlines.

a The 0.05 fractile wave height, b 0.95 fractile wave height, c 90 % confidence interval wave height, and d coefficient of variation of the 1,000-year return period at a depth of 50 m underwater offshore from the ria coastline of Iwate Prefecture. The two locations in the yellow boxes indicate a representative location offshore from a peninsular tip of the ria coastline and a representative offshore location in the closed-off section of a bay

Frequency distribution of tsunami wave height considering uncertainty: a at a location offshore from the peninsular tip where the coefficient of variation is large and b a location in the closed-off section of a bay where the coefficient of variation is small. These locations are in the yellow boxes in Fig. 13. The total number of calculated tsunami wave heights is 360. Here, μ is the average, σ is the standard deviation, c.o.v. is the coefficient of variation, min is the minimum value, and max is the maximum value

The above results show that when the results of stochastic tsunami wave height analysis limited to a Tohoku-type earthquake fault are analyzed, regional differences in uncertainty at the 90 % confidence interval and coefficient of variation of tsunami wave height clearly exist. In this study, we analyzed a Tohoku-type earthquake fault, but we believe that if the subject fault is changed, regional variations in the uncertainty of tsunami wave heights will also change.

4 Conclusions

We draw the following conclusions based on stochastic tsunami wave height hazard analysis of a fault having multiple slip distributions using a random source parameter model with a Tohoku-type earthquake fault zone and logic tree.

-

(1)

When the observation results of the Tohoku earthquake tsunami were compared with the results of the stochastic tsunami hazard analysis, the return period of the observation results at the location of the south Iwate offshore GPS wave gauge was equivalent to approximately 1,709 years (0.50 fractile wave height), and the return period at the location of the Fukushima Prefecture offshore GPS wave gauge was equivalent to approximately 600 years (0.50 fractile wave height). It was ascertained that the return period statistically determined from stochastic tsunami hazard analysis results differs by a fair amount depending on the region.

-

(2)

Analysis of the effect of the number of slip distribution patterns on stochastic tsunami hazard analysis results showed that the uncertainty of tsunami wave height increased as the number of slip distribution patterns increased, but for relatively small wave heights, there was almost no effect of the number of slip distribution patterns on the results of the hazard analysis.

-

(3)

When the uncertainty of tsunami wave height of a 1,000-year return period at a depth of 50 m underwater offshore from the Tohoku coast was examined, regional differences in uncertainty were clearly observed. In general, the 90 % confidence interval was high for locations where the wave height of each fractile point was high. Offshore of the Boso Peninsula of Chiba Prefecture, where the coefficient of variation reached the maximum, the difference in maximum wave height due to differences in slip distribution in the fault zone contributed greatly to the large coefficient of variation. At a ria coastline, the coefficient of variation was relatively large at a location offshore from the peninsular tip and relatively smaller at an offshore location in the closed-off section of a bay. We believe this is the effect of the submarine topography in a ria coastline.

As demonstrated in this study, important information for promoting regional disaster prevention activity can be obtained by quantifying and visualizing the uncertainty of tsunami wave heights by stochastic tsunami hazard analysis.

References

Aida I (1978) Reliability of a tsunami source model derived from fault parameters. J Phys Earth 26:57–73

Annaka T, Satake K, Sakakiyama T, Yanagisawa K, Shuto N (2007) Logic-tree approach for probabilistic tsunami hazard analysis and its applications to the Japanese coasts. Pure appl Geophys 164:577–592

Cairo MC, Neilson BL (1997) Modeling and generation random vectors with arbitrary marginal distributions and correlation matrix. Technical Report. Department of Industrial Engineering and Management Sciences, Northwestern University, Evanston

Freund LB, Barnett DM (1976) A two-dimensional analysis of surface deformation due to dip-slip faulting. Bull Seism Soc Am 66:667–675

Fujiwara H, Kawai S, Aoi S, Morikawa N, Senna S, Azuma H, Ooi M, Hao KX, Hasegawa N, Maeda T, Iwaki A, Wakamatsu K, Imoto M, Okumura T, Matsuyama H, Narita A (2013) Some improvements of seismic hazard assessment based on the 2011 Tohoku earthquake. Technical note of the National Research Institute for Earth Science and Disaster Prevention 379 (in Japanese)

Geist EL (1999) Local tsunamis and earthquake source parameters. Adv Geophys 39:117–209

Geist EL (2002) Complex earthquake rupture and local tsunamis. J Geophys Res 107(B5):2086. doi:10.1029/2000JB000139

Geist EL (2005) Local Tsunami Hazards in the Pacific Northwest from Cascadia Subduction Zone Earthquakes. U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1661-B

Geist EL, Dmowska R (1999) Local tsunamis and distributed slip at the source. Pure appl Geophys 154:485–512. doi:10.1007/s000240050241

Geist EL, Yoshioka S (1996) Source parameters controlling the generation and propagation of potential local tsunamis along the Cascadia margin. Nat Hazards 13:151–177

Hwang L, Divoky D (1970) Tsunami generation. J Geophys Res 75:6802–6817

Ishii Y, Dan K, Miyakoshi J, Takahashi H, Mori M, Fukuwa N (2013) Source modeling of hypothetical Nankai Trough, Japan, earthquake and strong ground motion prediction using the empirical Green’s functions. Shimizu Corporation Research Report 90:17–26 (in Japanese)

IUGG/IOC TIME Project (1997), Numerical method of tsunami simulation with the leap-frog scheme, Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission Manuals and Guides 35

Iwabuchi Y, Sugino H, Ebisawa K (2014) Guidelines for Developing Design Basis Tsunami based on Probabilistic Approach. JNES-RE-Report Series, JNES-RE-2013-2041

Japan Society of Civil Engineers (2011) A method for probabilistic tsunami hazard analysis, The Tsunami Evaluation Subcommittee, The Nuclear Civil Engineering Committee. Japan Society of Civil Engineers, Tokyo

Kawai H, Satoh M, Kawaguchi K, Seki K (2013) Characteristics of the 2011 Tohoku tsunami waveform acquired around Japan by NOWPHAS equipment. Coast Eng J 55(3):1350008. doi:10.1142/S0578563413500083

Lavallée D, Archuleta RJ (2003) Stochastic modeling of slip spatial complexities for the 1979 Imperial Valley, California, earthquake. Geophys Res Lett 30(5):1245. doi:10.1029/2002GL015839

Lavallée D, Archuleta RJ (2005) Coupling of the random properties of the source and the ground motion for the 1999 Chi Chi earthquake. Geophys Res Lett 32:L08311. doi:10.1029/2004GL022202

Lavallée D, Liu P, Archuleta RJ (2006) Stochastic model of heterogeneity in earthquake slip spatial distributions. Geophys J Int 165:622–640

Lin I, Tung CC (1982) A preliminary investigation of tsunami hazard. Bull Seism Soc Am 72:2323–2337

Liu PC, Archuleta RJ, Hartzell S (2006) Prediction of broadband ground-motion time histories: hybrid low/high frequency method with correlated random source parameters. Bull Seism Soc Am 96:2118–2130

Løvholt F, Pedersen G, Bazin S, Kühn D, Bredesen RE, Harbitz C (2012) Stochastic analysis of tsunami runup due to heterogeneous coseismic slip and dispersion. J Geophys Res 117:C03047. doi:10.1029/2011JC007616

Mai P, Beroza G (2002) A spatial random-field model to characterize complexity in earthquake slip. J Geophys Res 107(B11):2308. doi:10.1029/2001JB000588

McCloskey J, Antonioli A, Piatanesi A, Sieh K, Steacy S, Nalbant S, Cocco M, Giunchi C, Huang JD, Dunlop P (2007) Near-field propagation of tsunamis from megathrust earthquakes. Geophys Res Lett 34:L14316. doi:10.1029/2007GL030494

McCloskey J, Antonioli A, Piatanesi A, Sieh K, Steacy S, Nalbant S, Cocco M, Giunchi C, Huang JD, Dunlop P (2008) Tsunami threat in the Indian Ocean from a future megathrust earthquake west of Sumatra. Earth Planet Sci Lett 265:61–81. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2007.09.034

Ng MK, Leblond PH, Murty TS (1991) Simulation of tsunamis from great earthquakes on the Cascadia subduction zone. Science 250:1248–1251

Okada Y (1985) Surface deformation due to shear and tensile faults in a half-space. Bull Seism Soc Am 75:1135–1154

Pelayo AM, Wiens DA (1992) Tsunami earthquakes: slow thrust-faulting events in the accretionary wedge. J Geophys Res 97(B11):15321–15337

Rikitake T, Aida I (1988) Tsunami hazard probability in Japan. Bull Seism Soc Am 78:1268–1278

Sakai T, Takeda T, Soraoka H, Yanagisawa K, Annaka T (2006) Development of a probabilistic tsunami hazard analysis in Japan. In: Proceedings of ICONE14, international conference on nuclear engineering, Miami, FL

Somerville PG, Irikura K, Graves R, Sawada S, Wald D, Abrahamson N, Iwasaki Y, Kagawa T, Smith N, Kowada A (1999) Characterizing crustal earthquake slip models for the prediction of strong ground motion. Seism Res Lett 70:59–80

Song YT, Ji C, Fu LL, Zlotnicki V, Shum CK, Yi Y, Hjorleifsdottir V (2005) The 26 December 2004 tsunami source estimated from satellite radar altimetry and seismic waves. Geophys Res Lett 32:L20601. doi:10.1029/2005GL023683

Thio HK (2010) Probabilistic tsunami hazard analysis in California. Pacific Earthquake Engineering Research (PEER) Report 2010/108. University of California, Berkeley

Ward SN (1982) On tsunami nucleation: II. An instantaneous modulated line source. Phys Earth Planet Inter 27:273–285

Ward SN (2002) Tsunamis. In: Meyers RA (ed) The encyclopedia of physical science and technology, vol 17. Academic Press, London, pp 175–191

Whitmore PM (1993) Expected tsunami amplitudes and currents along the North American coast for Cascadia subduction zone earthquakes. Nat Hazards 8:59–73

Yong SC, Yong CK, Dongkyun K (2013) On the spatial pattern of the distribution of the tsunami run-up heights. Stoch Environ Res Risk Assess 27:1333–1346

Yoshida K, Miyakoshi K, Irikura K (2011) Source process of the 2011 off the Pacific coast of Tohoku earthquake inferred from waveform inversion with long-period strong-motion records. Earth Planet Space 63:577–582

Acknowledgments

We thank the anonymous reviewers who provided us with valuable comments and helped improve the manuscript. This research was partially supported by Specific Project Research (B70) for 2014 from the International Research Institute of Disaster Science (IRIDeS) at Tohoku University. This research was also supported by funding from Tokio Marine & Nichido Fire Insurance Co., Ltd., through the IRIDeS.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Fukutani, Y., Suppasri, A. & Imamura, F. Stochastic analysis and uncertainty assessment of tsunami wave height using a random source parameter model that targets a Tohoku-type earthquake fault. Stoch Environ Res Risk Assess 29, 1763–1779 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00477-014-0966-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00477-014-0966-4