Abstract

Introduction

The benefits of minimally invasive surgery are numerous; however, considerable variability exists in its application and there is a lack of standardized training for important advanced skills. Our goal was to determine whether participation in an advanced laparoscopic curriculum (ALC) results in improved laparoscopic suturing skills.

Methods and procedures

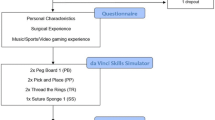

Study design was a prospective, randomized controlled trial. Surgery novices and trainees underwent baseline FLS training and were pre-tested on bench models. Participants were stratified by pre-test score and randomized to undergo either further FLS training (control group) or ALC training (intervention group). All were post-tested on the same bench model. Tests for differences between post-test scores of cohorts were performed using least squared means. Multivariable regression identified predictors of post-test score, and Wilcoxon rank sum test assessed for differences in confidence improvement in laparoscopic suturing ability between groups.

Results

Between November 2018 and May 2019, 25 participants completed the study (16 females; 9 males). After adjustment for relevant variables, participants randomized to the ALC group had significantly higher post-test scores than those undergoing FLS training alone (mean score 90.50 versus 82.99, p = 0.001). The only demographic or other variables found to predict post-test score include level of training (p = 0.049) and reported years of video gaming (p = 0.034). There was no difference in confidence improvement between groups.

Conclusions

Training using the ALC as opposed to basic laparoscopic skills training only is associated with superior advanced laparoscopic suturing performance without affecting improvement in reported confidence levels. Performance on advanced laparoscopic suturing tasks may be predicted by lifetime cumulative video gaming history and year of training but does not appear to be associated with other factors previously studied in relation to basic laparoscopic skills, such as surgical career aspiration or musical ability.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Soper NJ, Brunt LM, Kerbl K (1994) Laparoscopic general surgery. N Engl J Med 330(6):409–419. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199402103300608

Park AE, Lee TH (2011) Evolution of minimally invasive surgery and its impact on surgical residency training. In: Minimally invasive surgical oncology. Springer, Berlin, pp 11–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-45021-4_2

Park A, Witzke D, Donnelly M (2002) Ongoing deficits in resident training for minimally invasive surgery. J Gastrointest Surg 6(3):501–507

Rattner DW, Apelgren KN, Eubanks WS (2001) The need for training opportunities in advanced laparoscopic surgery. Surg Endosc 15(10):1066–1070. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004640080021

Qureshi A, Vergis A, Jimenez C et al (2011) MIS training in Canada: a national survey of general surgery residents. Surg Endosc 25(9):3057–3065. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-011-1670-9

Anton NE, Sawyer JM, Korndorffer JR et al (2018) Developing a robust suturing assessment: validity evidence for the intracorporeal suturing assessment tool. Surgery 163(3):560–564. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2017.10.029

Stefanidis D, Hope WW, Korndorffer JR, Markley S, Scott DJ (2010) Initial laparoscopic basic skills training shortens the learning curve of laparoscopic suturing and is cost-effective. J Am Coll Surg 210(4):436–440. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.12.015

Nepomnayshy D, Alseidi AA, Fitzgibbons SC, Stefanidis D (2016) Identifying the need for and content of an advanced laparoscopic skills curriculum: results of a national survey. Am J Surg 211(2):421–425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2015.10.009

Mattar SG, Alseidi AA, Jones DB et al (2013) General surgery residency inadequately prepares trainees for fellowship: results of a survey of fellowship program directors. Ann Surg 258(3):440–449. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182a191ca

Nepomnayshy D, Whitledge J, Birkett R et al (2015) Evaluation of advanced laparoscopic skills tasks for validity evidence. Surg Endosc 29(2):349–354. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-014-3674-8

Watanabe Y, McKendy KM, Bilgic E et al (2016) New models for advanced laparoscopic suturing: taking it to the next level. Surg Endosc 30(2):581–587. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-015-4242-6

Bilgic E, Watanabe Y, Nepomnayshy D et al (2017) Multicenter proficiency benchmarks for advanced laparoscopic suturing tasks. Am J Surg 213(2):217–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2016.07.033

FLS Program Description (2010) https://www.flsprogram.org/index/fls-program-description/. Accessed 14 Mar 2018

Ritter EM, Scott DJ (2007) Design of a proficiency-based skills training curriculum for the fundamentals of laparoscopic surgery. Surg Innov 14(2):107–112. https://doi.org/10.1177/1553350607302329

Zhang L, Sankaranarayanan G, Arikatla VS et al (2013) Characterizing the learning curve of the VBLaST-PT(©) (Virtual Basic Laparoscopic Skill Trainer). Surg Endosc 27(10):3603–3615. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-013-2932-5

Rosser JC (1997) Skill acquisition and assessment for laparoscopic surgery. Arch Surg 132(2):200–204. https://doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.1997.01430260098021

Shapiro SJ, Paz-Partlow M, Daykhovsky L, Gordon LA (1996) The use of a modular skills center for the maintenance of laparoscopic skills. Surg Endosc 10(8):816–819. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00189541

Fraser SA, Klassen DR, Feldman LS, Ghitulescu GA, Stanbridge D, Fried GM (2003) Evaluating laparoscopic skills. Surg Endosc 17(6):964–967. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-002-8828-4

Schwenk W, Haase O, Neudecker J, Müller JM (2005) Short term benefits for laparoscopic colorectal resection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 45(3):CD003145. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003145.pub2

Salminen PTP, Hiekkanen HI, Rantala APT, Ovaska JT (2007) Comparison of long-term outcome of laparoscopic and conventional nissen fundoplication: a prospective randomized study with an 11-year follow-up. Ann Surg 246(2):201–206. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.sla.0000263508.53334.af

Sauerland S, Jaschinski T, Neugebauer EA (2010) Laparoscopic versus open surgery for suspected appendicitis. Cochrane Datab Syst Rev 23(2):1339. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001546.pub3

Fullum TM, Ladapo JA, Borah BJ, Gunnarsson CL (2010) Comparison of the clinical and economic outcomes between open and minimally invasive appendectomy and colectomy: evidence from a large commercial payer database. Surg Endosc 24(4):845–853. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-009-0675-0

Darzi S, Munz Y (2004) The impact of minimally invasive surgical techniques. Annu Rev Med 55(1):223–237. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.med.55.091902.105248

Xu T, Hutfless SM, Cooper MA, Zhou M, Massie AB, Makary MA (2015) Hospital cost implications of increased use of minimally invasive surgery. JAMA Surg 150(5):489–490. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2014.4052

Swanstrom LL, Park A, Arregui M, Franklin M, Smith CD, Blaney C (2006) Bringing order to the chaos: developing a matching process for minimally invasive and gastrointestinal postgraduate fellowships. Ann Surg 243(4):431–435. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.sla.0000205217.45477.25

Richards MK, McAteer JP, Drake FT, Goldin AB, Khandelwal S, Gow KW (2015) A national review of the frequency of minimally invasive surgery among general surgery residents: assessment of ACGME case logs during 2 decades of general surgery resident training. JAMA Surg 150(2):169–172. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2014.1791

McGaghie WC, Draycott TJ, Dunn WF, Lopez CM, Stefanidis D (2011) Evaluating the impact of simulation on translational patient outcomes. Simul Healthc 6(Suppl):S42–S47. https://doi.org/10.1097/SIH.0b013e318222fde9

McGaghie DWC, Issenberg DSB, Cohen MER, Barsuk DJH, Wayne DDB (2011) Does simulation-based medical education with deliberate practice yield better results than traditional clinical education? A meta-analytic comparative review of the evidence. Acad Med 86(6):706–711. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e318217e119

Kolozsvari NO, Feldman LS, Vassiliou MC, Demyttenaere S, Hoover ML (2011) Sim one, do one, teach one: considerations in designing training curricula for surgical simulation. J Surg Educ 68(5):421–427. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2011.03.010

Dehabadi M, Fernando B, Berlingieri P (2014) The use of simulation in the acquisition of laparoscopic suturing skills. Int J Surg 12(4):258–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.01.022

Korndorffer JR Jr, Dunne JB, Sierra R, Stefanidis D, Touchard CL, Scott DJ (2005) Simulator training for laparoscopic suturing using performance goals translates to the operating room. J Am Coll Surg 201(1):23–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2005.02.021

Van Sickle KR, Ritter EM, Baghai M et al (2008) Prospective, randomized, double-blind trial of curriculum-based training for intracorporeal suturing and knot tying. J Am Coll Surg 207(4):560–568. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.05.007

Madan AK, Frantzides CT, Park WC, Tebbit CL, Kumari NVA, O’Leary PJ (2005) Predicting baseline laparoscopic surgery skills. Surg Endosc 19(1):101–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-004-8123-7

Panait L, Larios JM, Brenes RA, Fancher TT, Ajemian MS, Dudrick SJ, Sanchez JA (2011) Surgical skills assessment of applicants to general surgery residency. J Surg Res 170(2):189–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2011.04.006

Kennedy AM, Boyle EM, Traynor O, Walsh T, Hill ADK (2011) Video gaming enhances psychomotor skills but not visuospatial and perceptual abilities in surgical trainees. J Surg Educ 68(5):414–420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2011.03.009

Anders EK (2008) Deliberate practice and acquisition of expert performance: a general overview. Acad Emerg Med 15(11):988–994. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00227.x

Choudhry NK, Fletcher RH, Soumerai SB (2005) Systematic review: the relationship between clinical experience and quality of health care. Ann Intern Med 142(4):260–273

Kerlin MP, Epstein A, Kahn JM et al (2018) Physician-level variation in outcomes of mechanically ventilated patients. Ann Am Thorac Soc 15(3):371–379. https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201711-867OC

Halm EA, Lee C, Chassin MR (2002) Is volume related to outcome in health care? A systematic review and methodologic critique of the literature. Ann Intern Med 137(6):511–520

McGaghie WC (2008) Research opportunities in simulation-based medical education using deliberate practice. Acad Emerg Med 15(11):995–1001. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00246.x

Bhatti NI, Ahmed A (2015) Improving skills development in residency using a deliberate-practice and learner-centered model. The Laryngoscope 125(S8):S1–S14. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.25434

Davis DA, Mazmanian PE, Fordis M, Van Harrison R, Thorpe KE, Perrier L (2006) Accuracy of physician self-assessment compared with observed measures of competence: a systematic review. JAMA 296(9):1094–1102. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.296.9.1094

Leopold SS, Morgan HD, Kadel NJ, Gardner GC, Schaad DC, Wolf FM (2005) Impact of educational intervention on confidence and competence in the performance of a simple surgical task. J Bone Joint Surg Am 87(5):1031–1037. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.D.02434

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award Number UL1TR001412. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. The authors also gratefully acknowledge the contributions of Jon Rossman and Thomas Springer of UB RISE.

Funding

This work was funded by an intradepartmental grant without ID number from the Department of Surgery at the University at Buffalo.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosures

Ms. Towle-Miller has nothing to disclose. Dr. Schwaitzberg reports personal fees from Nu View Surgical, personal fees from Acuity Bio, personal fees from Activ Surgical, personal fees from Human Extensions, personal fees from Levitra Magnetics, and personal fees from Arch Therepeutics, outside the submitted work. Drs. Train, Hu, Narvaez, Noyes, Wilding, Cavuoto, and Hoffman have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Train, A.T., Hu, J., Narvaez, J.R.F. et al. Teaching surgery novices and trainees advanced laparoscopic suturing: a trial and tribulations. Surg Endosc 35, 5816–5826 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-020-08067-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-020-08067-5