Abstract

Background

Despite proven safety and efficacy, rates of laparoscopy for rectal cancer in the US are low. With reports of inferiority with laparoscopy compared to open surgery, and movements to develop accredited centers, investigating utilization and predictors of laparoscopy are warranted. Our goal was to evaluate current utilization and identify factors impacting use of laparoscopic surgery for rectal cancer.

Methods

The Premier™ Hospital Database was reviewed for elective inpatient rectal cancer resections (1/1/2010–6/30/2015). Patients were identified by ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes, and then stratified into open or laparoscopic approaches by ICD-9-CM procedure codes or billing charge. Logistic multivariable regression identified variables predictive of laparoscopy. The Cochran–Armitage test assessed trend analysis. The main outcome measures were trends in utilization and factors independently associated with use of laparoscopy.

Results

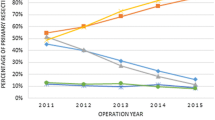

3336 patients were included—43.8% laparoscopic (n = 1464) and 56.2% open (n = 1872). Use of laparoscopy increased from 37.6 to 55.3% during the study period (p < 0.0001). General surgeons performed the majority of all resections, but colorectal surgeons were more likely to approach rectal cancer laparoscopically (41.31 vs. 36.65%, OR 1.082, 95% CI [0.92, 1.27], p < 0.3363). Higher volume surgeons were more likely to use laparoscopy than low-volume surgeons (OR 3.72, 95% CI [2.64, 5.25], p < 0.0001). Younger patients (OR 1.49, 95% CI [1.03, 2.17], p = 0.036) with minor (OR 2.13, 95% CI [1.45, 3.12], p < 0.0001) or moderate illness severity (OR 1.582, 95% CI [1.08, 2.31], p < 0.0174) were more likely to receive a laparoscopic resection. Teaching hospitals (OR 0.842, 95% CI [0.710, 0.997], p = 0.0463) and hospitals in the Midwest (OR 0.69, 95% CI [0.54, 0.89], p = 0.0044) were less likely to use laparoscopy. Insurance status and hospital size did not impact use.

Conclusions

Laparoscopy for rectal cancer steadily increased over the years examined. Patient, provider, and regional variables exist, with hospital status, geographic location, and colorectal specialization impacting the likelihood. However, surgeon volume had the greatest influence. These results emphasize training and surgeon-specific outcomes to increase utilization and quality in appropriate cases.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Senagore AJ (2015) Adoption of laparoscopic colorectal surgery: it was quite a journey. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 28:131–134

Carmichael JC, Masoomi H, Mills S, Stamos MJ, Nguyen NT (2011) Utilization of laparoscopy in colorectal surgery for cancer at academic medical centers: does site of surgery affect rate of laparoscopy? Am Surg 77:1300–1304

Nguyen NT, Nguyen B, Shih A, Smith B, Hohmann S (2013) Use of laparoscopy in general surgical operations at academic centers. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 9:15–20

Row D, Weiser MR (2010) An update on laparoscopic resection for rectal cancer. Cancer Control. 17:16–24

Young M, Pigazzi A (2014) Total mesorectal excision: open, laparoscopic or robotic. Recent Results Cancer Res 203:47–55

Son GM, Kim JG, Lee JC et al (2010) Multidimensional analysis of the learning curve for laparoscopic rectal cancer surgery. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 20:609–617

Li GX, Yan HT, Yu J, Lei ST, Xue Q, Cheng X (2006) Learning curve of laparoscopic resection for rectal cancer. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao 26:535–538

Liang JW, Zhang XM, Zhou ZX, Wang Z, Bi JJ (2011) Learning curve of laparoscopic-assisted surgery for rectal cancer. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 91:1698–1701

Lujan J, Gonzalez A, Abrisqueta J et al (2014) The learning curve of laparoscopic treatment of rectal cancer does not increase morbidity. Cir Esp 92:485–490

Nandakumar G, Fleshman JW (2010) Laparoscopy for rectal cancer. Surg Oncol Clin N Am 19:793–802

Lacy AM, Garcia-Valdecasas JC, Pique JM et al (1995) Short-term outcome analysis of a randomized study comparing laparoscopic vs open colectomy for colon cancer. Surg Endosc 9:1101–1105

Lacy AM, Garcia-Valdecasas JC, Delgado S et al (2002) Laparoscopy-assisted colectomy versus open colectomy for treatment of non-metastatic colon cancer: a randomised trial. Lancet 359:2224–2229

Lacy AM, Delgado S, Castells A et al (2008) The long-term results of a randomized clinical trial of laparoscopy-assisted versus open surgery for colon cancer. Ann Surg 248:1–7

Guillou PJ, Quirke P, Thorpe H et al (2005) Short-term endpoints of conventional versus laparoscopic-assisted surgery in patients with colorectal cancer (MRC CLASICC trial): multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 365:1718–1726

Bonjer HJ, Hop WC, Nelson H et al (2007) Laparoscopically assisted vs open colectomy for colon cancer: a meta-analysis. Arch Surg 142:298–303

Jayne DG, Guillou PJ, Thorpe H et al (2007) Randomized trial of laparoscopic-assisted resection of colorectal carcinoma: 3-year results of the UK MRC CLASICC Trial Group. J Clin Oncol 25:3061–3068

Buunen M, Veldkamp R, Hop WC et al (2009) Survival after laparoscopic surgery versus open surgery for colon cancer: long-term outcome of a randomised clinical trial. Lancet Oncol 10:44–52

Veldkamp R, Kuhry E, Hop WC et al (2005) Laparoscopic surgery versus open surgery for colon cancer: short-term outcomes of a randomised trial. Lancet Oncol 6:477–484

COST Trial Study Group (2004) A comparison of laparoscopically assisted and open colectomy for colon cancer. N Engl J Med 350:2050–2059

Lujan J, Valero G, Hernandez Q, Sanchez A, Frutos MD, Parrilla P (2009) Randomized clinical trial comparing laparoscopic and open surgery in patients with rectal cancer. Br J Surg 96:982–989

Jeong SY, Park JW, Nam BH et al (2014) Open versus laparoscopic surgery for mid-rectal or low-rectal cancer after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (COREAN trial): survival outcomes of an open-label, non-inferiority, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 15:767–774

Kang SB, Park JW, Jeong SY et al (2010) Open versus laparoscopic surgery for mid or low rectal cancer after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (COREAN trial): short-term outcomes of an open-label randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 11:637–645

Bonjer HJ, Deijen CL, Abis GA et al (2015) A randomized trial of laparoscopic versus open surgery for rectal cancer. N Engl J Med 372:1324–1332

Green BL, Marshall HC, Collinson F et al (2013) Long-term follow-up of the Medical Research Council CLASICC trial of conventional versus laparoscopically assisted resection in colorectal cancer. Br J Surg 100:75–82

Jayne DG, Thorpe HC, Copeland J, Quirke P, Brown JM, Guillou PJ (2010) Five-year follow-up of the Medical Research Council CLASICC trial of laparoscopically assisted versus open surgery for colorectal cancer. Br J Surg 97:1638–1645

Fleshman J, Branda M, Sargent DJ et al (2015) Effect of laparoscopic-assisted resection vs open resection of stage II or III rectal cancer on pathologic outcomes: the ACOSOG Z6051 randomized clinical trial. JAMA 314:1346–1355

Stevenson AR, Solomon MJ, Lumley JW et al (2015) Effect of laparoscopic-assisted resection vs open resection on pathological outcomes in rectal cancer: the ALaCaRT randomized clinical trial. JAMA 314:1356–1363

All Patient Refined Diagnostic Related Groups Methodology Overview. v20.0

M Health Information Systems. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nis/APR-DRGsV20MethodologyOverviewandBibliography.pdf. Accessed June, 2015

Yamamoto S, Inomata M, Katayama H et al (2014) Short-term surgical outcomes from a randomized controlled trial to evaluate laparoscopic and open D3 dissection for stage II/III colon cancer: Japan Clinical Oncology Group Study JCOG 0404. Ann Surg 260:23–30

Rullier E, Sa Cunha A, Couderc P, Rullier A, Gontier R, Saric J (2003) Laparoscopic intersphincteric resection with coloplasty and coloanal anastomosis for mid and low rectal cancer. Br J Surg 90:445–451

Morino M, Parini U, Giraudo G, Salval M, Brachet Contul R, Garrone C (2003) Laparoscopic total mesorectal excision: a consecutive series of 100 patients. Ann Surg 237:335–342

Anthuber M, Fuerst A, Elser F, Berger R, Jauch KW (2003) Outcome of laparoscopic surgery for rectal cancer in 101 patients. Dis Colon Rectum 46:1047–1053

Feliciotti F, Guerrieri M, Paganini AM et al (2003) Long-term results of laparoscopic versus open resections for rectal cancer for 124 unselected patients. Surg Endosc 17:1530–1535

Dulucq JL, Wintringer P, Stabilini C, Mahajna A (2005) Laparoscopic rectal resection with anal sphincter preservation for rectal cancer: long-term outcome. Surg Endosc 19:1468–1474

Aziz O, Constantinides V, Tekkis PP et al (2006) Laparoscopic versus open surgery for rectal cancer: a meta-analysis. Ann Surg Oncol 13:413–424

Fleshman J (2016) Current status of minimally invasive surgery for rectal cancer. J Gastrointest Surg 20:1056–1064

Glasgow SC, Morris AM, Baxter NN et al (2016) Development of The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons’ rectal cancer surgery checklist. Dis Colon Rectum 59:601–606

Fleshman JW (2013) Multidisciplinary treatment of rectal cancer: the way of the future. JAMA Surg 148:778

Dietz DW (2013) Consortium, for optimizing surgical treatment of rectal cancer (OSTRiCh). Multidisciplinary management of rectal cancer: the OSTRICH. J Gastrointest Surg. 17:1863–1868

Kemp JA, Finlayson SR (2008) Outcomes of laparoscopic and open colectomy: a national population-based comparison. Surg Innov 15:277–283

Huang MJ, Liang JL, Wang H, Kang L, Deng YH, Wang JP (2011) Laparoscopic-assisted versus open surgery for rectal cancer: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials on oncologic adequacy of resection and long-term oncologic outcomes. Int J Colorectal Dis 26:415–421

Keller DS, Parikh N, Senagore AJ (2016) Predicting opportunities to increase utilization of laparoscopy for colon cancer. Surg Endosc 31(4):1855–1862

Ricciardi R, Roberts PL, Read TE, Baxter NN, Marcello PW, Schoetz DJ (2011) Presence of specialty surgeons reduces the likelihood of colostomy after proctectomy for rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 54:207–213

Borowski DW, Kelly SB, Bradburn DM et al (2007) Impact of surgeon volume and specialization on short-term outcomes in colorectal cancer surgery. Br J Surg 94:880–889

Barbas AS, Turley RS, Mantyh CR, Migaly J (2012) Effect of surgeon specialization on long-term survival following colon cancer resection at an NCI-designated cancer center. J Surg Oncol 106:219–223

Hohenberger W, Merkel S, Hermanek P (2013) Volume and outcome in rectal cancer surgery: the importance of quality management. Int J Colorectal Dis 28:197–206

Oliphant R, Nicholson GA, Horgan PG et al (2013) Contribution of surgical specialization to improved colorectal cancer survival. Br J Surg 100:1388–1395

Monson JR, Probst CP, Wexner SD et al (2014) Failure of evidence-based cancer care in the United States: the association between rectal cancer treatment, cancer center volume, and geography. Ann Surg 260:625–631; discussion 631

Schrag D, Panageas KS, Riedel E et al (2002) Hospital and surgeon procedure volume as predictors of outcome following rectal cancer resection. Ann Surg 236:583–592

Baek JH, Alrubaie A, Guzman EA et al (2013) The association of hospital volume with rectal cancer surgery outcomes. Int J Colorectal Dis 28:191–196

Paquette IM, Kemp JA, Finlayson SR (2010) Patient and hospital factors associated with use of sphincter-sparing surgery for rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 53:115–120

Ricciardi R, Virnig BA, Madoff RD, Rothenberger DA, Baxter NN (2007) The status of radical proctectomy and sphincter-sparing surgery in the United States. Dis Colon Rectum 50:1119–1127; discussion 1126

Ricciardi R, Roberts PL, Read TE, Baxter NN, Marcello PW, Schoetz DJ (2011) Who performs proctectomy for rectal cancer in the United States. Dis Colon Rectum 54:1210–1215

Aquina CT, Probst CP, Becerra AZ et al (2016) High volume improves outcomes: the argument for centralization of rectal cancer surgery. Surgery 159:736–748

Wibe A, Moller B, Norstein J et al (2002) A national strategic change in treatment policy for rectal cancer–implementation of total mesorectal excision as routine treatment in Norway. A national audit. Dis Colon Rectum 45:857–866

Guren MG, Kørner H, Pfeffer F et al (2015) Nationwide improvement of rectal cancer treatment outcomes in Norway, 1993-2010. Acta Oncol 54:1714–1722

Martling AL, Holm T, Rutqvist LE, Moran BJ, Heald RJ, Cedemark B (2000) Effect of a surgical training programme on outcome of rectal cancer in the County of Stockholm. Stockholm Colorectal Cancer Study Group, Basingstoke Bowel Cancer Research Project. Lancet 356:93–96

Khani MH, Smedh K (2010) Centralization of rectal cancer surgery improves long-term survival. Colorectal Dis 12:874–879

American College of Surgeons, Quality Programs. National Accreditation Program for Rectal Cancer. https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/cancer/naprc. Assessed March 17, 2017

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the Medtronic Minimally Invasive Therapies Group for access to the data source and assistance with statistical modeling.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosures

Ms. Qiu is employed by Medtronic, which gave access to the data source and assistance with statistical analysis. Drs. Keller and Senagore have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Appendix: Rectal procedures and stoma codes

Appendix: Rectal procedures and stoma codes

46.04 Resection of exteriorized segment of large intestine |

48.40 Pull-through resection of rectum, not otherwise specified |

48.42 Laparoscopic pull-through resection of rectum |

48.43 Open pull-through resection of rectum |

48.50 Abdominoperineal resection of the rectum, not otherwise specified |

48.51 Laparoscopic abdominoperineal resection of the rectum |

48.52 Open abdominoperineal resection of the rectum |

48.49 Other pull-through resection of rectum |

48.59 Other abdominoperineal resection of the rectum |

48.69 Other resection of rectum, (Partial proctectomy, Rectal resection NOS) |

48.62 Anterior resection of rectum with synchronous colostomy |

48.63 Other anterior resection of rectum |

48.64 Posterior resection of rectum |

48.65 Duhamel abdominoperineal pull-through |

17.36 Laparoscopic Sigmoidectomy |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Keller, D.S., Qiu, J. & Senagore, A.J. Predicting opportunities to increase utilization of laparoscopy for rectal cancer. Surg Endosc 32, 1556–1563 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-017-5844-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00464-017-5844-y