Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly altered the world as we know it. Service delivery for the instrumental evaluation of dysphagia in hospitalized patients has been significantly impacted. In many institutions, instrumental assessment was halted or eliminated from the clinical workflow, leaving clinicians without evidence-based gold standards to definitively evaluate swallowing function. The aim of this study was to describe the outcomes of an early, but measured return to the use of instrumental dysphagia assessment in hospitalized patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Data was extracted via a retrospective medical record review on all patients on whom a swallowing consult was placed. Information on patient demographics, type of swallowing evaluation, and patient COVID status was recorded and analyzed. Statistics on staff COVID status were also obtained. Over the study period, a total of 4482 FEES evaluations and 758 MBS evaluations were completed. During this time, no staff members tested COVID-positive due to workplace exposure. Results strongly support the fact that a measured return to instrumental assessment of swallowing is an appropriate and reasonable clinical shift during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

COVID-19 has changed every aspect of the world in which we live and has impacted all levels of our existence, globally impacting our social, professional, and economic landscape. Since the start of the pandemic, governmental, educational, and healthcare systems have worked tirelessly to implement protocols to keep the public at large safe from COVID-19. One of the greatest impacts has been on our healthcare system. Hospitals worldwide have worked to develop protocols to continue to provide life-saving treatments to patients both with and without the virus. These protocols involve minimizing both patient and staff exposure to the virus. Controlling viral transmission to healthcare workers is paramount as not doing so could effectively halt healthcare delivery completely. For this reason, the development of protocols for keeping both patients and staff safe has been the focus of healthcare organizations worldwide since the start of the pandemic.

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is the virus that causes Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). The epicenter of the virus in the human body is in the upper digestive tract resulting in the viral load being extremely high in the mucosa of the nasal, oral, and pharyngeal cavities [1]. The transmission of SARS-CoV-2 is primarily through droplets, however, given the location in the upper respiratory tract, airborne transmission can also be responsible for viral spread. The location of the SARS-CoV-2 virus is a significant concern for those hospital procedures involving the airway, many of which are critically important in keeping patients alive. The safety of life-saving procedures like intubation were among the earliest considered in order for patients to receive critical respiratory support via ventilator and to undergo critical surgical procedures. Medical services like Otolaryngology, Pulmonology, Gastroenterology, and Speech-Language Pathology were particularly engaged in these early initiatives given the fact that their clinical procedures are tethered to the upper digestive tract and airway.

For speech-language pathologists, swallowing assessments are a critical tool for assessment of dysphagia. The two objective assessments that serve as the gold standard for swallowing evaluation are Fiberoptic Endoscopic Evaluation of Swallowing (FEES) and Videofluoroscopic Swallowing Study (VFSS) or Modified Barium Swallow Study (MBS). Given the high viral load in the airway, risk of cough, risk of droplet and airborne transmission, the SLP’s necessary close proximity to the patient, and the patient’s inability to wear a mask for food trials, both types of objective evaluations put speech-language pathologists at a high risk for airborne transmission of COVID-19 [2].

There has been much clinical discussion surrounding the use of FEES in the context of COVID given the fact that speech-language pathologists are at high risk for transmission of COVID due to the nature of the endoscopy assessment alone. Many experts in the field consider FEES or any endoscopic procedure to be an aerosol generating procedure (AGP) [1, 3, 4], while others do not [5]. While the literature does not provide a consensus on whether endoscopy is an AGP [6], the literature does agree that performing FEES puts providers at significant risk for transmission of COVID [5, 7, 8]. Furthermore, given close proximity to patient, the patient’s decreased ability to wear a mask during food trials, and high risk of droplet and airborne precautions, some published clinical recommendations from early in the pandemic reflect caution regarding the use of such objective assessment tools [9].

Discussion about FEES and COVID has called into question the best practice for swallowing assessment during the pandemic. Concerns over staff safety have resulted in a variety of published recommendations for best practice of swallowing assessment in the context of COVID. These vary from recommendations for types of personal protective equipment (PPE) for patients based on risk level [1], to prioritization for use of FEES on only the most critically ill patients [10], to the use of videofluoroscopy instead of FEES for objective evaluations [11]. In the context of concern for safety of staff, other experts encourage specialists to utilize non-instrumental methods for assessing swallowing [4]. Unfortunately, many of the non-instrumental methods available to SLPs (clinical swallow evaluation (CSE), cervical auscultation, patient report of symptoms) are not evidence based when used for diagnosing dysphagia or determining aspiration status. While the question of how to safely evaluate swallowing in this context is critically important, it is equally important to ask how to safely incorporate known best practice guidelines into clinical practice during this time. Additionally, the vast majority of the studies published are theoretically based, that is to say, they present little in the way of evidence for support of any shift in clinical delivery of swallowing assessment, nor do they speak definitively to the safety of the staff under such circumstances.

Decisions to protect staff by having them keep a 2-m distance [10] or conduct non-instrumental swallowing assessments are sound choices for the safety of the staff and may have served as a reasonable solution in the early stages of the pandemic when less was known about the COVID-19 virus. However, this public health crisis is likely to be a reality for the foreseeable future and steps must be taken to ensure we are providing the best possible care to our patients in the context of keeping staff safe. In our large, urban, tertiary care center, FEES and MBS are an extremely common procedure as all patients who fail a swallow screen are evaluated using an objective assessment. The early decision to halt the use of these gold standards of assessment, while necessary, was incredibly disruptive to our service and did not allow our SLPs to provide the evidence-based practice that was standard of care in our institution.

The purpose of this study was to describe a measured return to instrumental assessment in our large, urban, tertiary care center and to determine if re-implementing the use of the clinical gold standard for dysphagia assessment was safe for our staff during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

Procedure

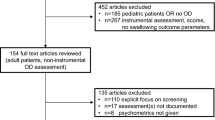

This study was conducted as a retrospective medical record review and was approved by the Yale School of Medicine and Southern Connecticut State University’s Institutional Review Board. Data extraction took place from the electronic medical record during a period of time between 3/1/2020 and 10/6/2021.

Patient Population

Participants for this retrospective study were all hospitalized patients over the age of 18 in our tertiary care facility for whom a swallowing consult had been placed by their medical provider. Patients who did not have a swallowing consult placed by their medical team were excluded from the dataset.

Data Extraction

The data extraction was completed through the Yale Center for Clinical Investigation (YCCI) at Yale University School of Medicine by the Joint Data Analytics Team. The following data points were extracted from the medical record: patient demographics, date of swallow evaluation consult and evaluation, type of swallowing assessment performed (FEES, MBS, CSE, swallow screening), and COVID status of hospitalization. Additionally, data were collected on the COVID status of individual patients that underwent FEES. Per institutional policy, a positive COVID hospitalization was defined as an encounter in which: 1. The patient had a positive COVID lab resulted during hospitalization; OR 2. The patient had a positive COVID lab up to 7 days before admission AND did not have a negative result between the positive result and admission. Given the clinical significance of performing endoscopy on a patient who has active COVID infection, for the purpose of this study, a distinction was made between COVID-positive hospitalizations and COVID-positive FEES evaluations. A COVID-positive FEES was defined as an evaluation that was conducted on a patient who had a COVID-positive test within 7 days.

In addition to the extracted data, information on incidence of COVID-positive providers and information on contact tracing were extracted from departmental statistics. During the study period, staff participated in testing procedures per hospital policy. Hospital policy dictated that any staff who tested positive engage in contact tracing procedures per Hospital Leadership and Department of Occupational Health policies. With regard to patient transmission of COVID-19 during hospitalization, any patient who was determined to be negative and then became positive during the hospitalization was subject to contact tracing. In this circumstance, occupational health would contact management regarding staff that were in contact with the patient during the time in question.

Data Analysis

In order to analyze the extracted data for this observational study, raw data was filtered and frequency counts were determined and used to summarize data in order to provide descriptive statistics of study outcomes. Frequency counts for number of swallowing evaluations, type of swallowing evaluations, and patient COVID status were recorded and summarized. Departmental statistics on staff infection rates were obtained from administration. Hospital policy dictated that if a staff member tested positive for COVID, the employee was required to complete an Exposure Report. Infection Prevention was responsible for review of each report and made the final determination about whether or not the exposure occurred in the workplace.

Clinical Protocols and Algorithms

Clinical decisions about the to return to pre-pandemic clinical practice was a dynamic process over the study period, evolving as information about the virus become more readily available. During this time, decisions about patient facing clinical care were determined by the Speech-Language Pathology Medical Director and Manager in accordance with Health System Guidelines. A sampling of the clinical algorithms for service delivery during the study period can be found in Appendix A. Algorithm A represents the initial clinical decision making pathway for SLPs performing swallowing evaluations in April 2020, early in the pandemic. This algorithm shifted and changed over time to align with new scientific evidence about the virus as well as to organizational policy. Algorithm B represents the clinical decision making pathway at the end of the study period. Details of each stepwise change in the algorithm is beyond the scope of this study; however, information in Table 4 highlights the evolution of the algorithms and the major shifts in decision making as they relate to instrumental swallowing evaluation over time. PPE during the study period included N-95 masks, gloves, and gowns, and eye protection for the entire period. Head and foot coverings were optional at our institution.

Results

Study Sample: Hospitalizations

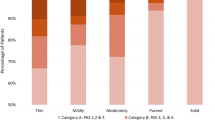

The extraction sample consisted of 9096 consults placed for swallowing evaluations over 6278 unique hospitalizations. Of these hospitalizations, 5839 were COVID-negative and 439 were COVID-positive (Table 1). When considering hospitalizations overall, 2987 had at least one FEES, 3,886 had at least one Yale Swallow Protocol (YSP), 339 had at least one Clinical Swallow Evaluation (CSE), and 665 had at least one Modified Barium Swallow (MBS). Frequency counts for COVID-positive vs COVID-negative hospitalizations can be found in Table 1.

Study Sample: Swallowing Evaluations

Over the study period, a total of 4482 FEES evaluations and 758 MBS evaluations were completed (Table 2). Clinical practice at our institution dictates that eligible patients receive a swallow screen (YSP) prior to instrumental exam. Of the 4482 FEES, 2029 had YSP and 2453 did not. Of the 758 MBSs, 192 had YSP and 566 did not. Total frequencies of non-instrumental assessment were 4274 YSPs and 408 CSEs. Graph 1 indicates the number of total evaluations completed by month over the course of the study period. Graph 2 indicates the number and type of swallowing evaluations completed each month.

Seven-hundred thirty-five swallowing consults were placed on patients that were deemed to have a COVID-positive hospitalization during the study period. During those COVID-positive hospitalizations, 312 FEES were completed. Thirty-eight MBS, 240 YSP, and 26 CSE were conducted during COVID-positive hospitalizations (Table 3). Of the 312 FEES performed during COVID-positive hospitalizations, 76 underwent COVID-positive FEES. These patients had a documented positive COVID result within 7 days of the evaluation (Table 4).

Staff Outcomes and Contact Tracing Data

Departmental statistics included all inpatient SLP staff and indicated that during the study period, no speech-language pathology (SLP) staff members who performed objective swallowing assessments had a COVID-positive test result related to workplace exposure. COVID testing procedures were conducted per institutional policy, and in accordance with national and local guidance over the course of the study period. At no time during the study period, was the Speech-Language Pathology Department contacted with concern of COVID-19 spread due to scoping procedures or for the purposes of contact tracing for SLP staff.

Discussion

The COVID-19 virus has altered the landscape of our world forever. This is particularly true in the healthcare field. For clinicians whose assessments rely on procedures that involve the airway, protocols have changed significantly in order to protect both patients and staff. The focus of this investigation is to determine if a measured return to instrumental swallowing assessments is safe in the context of the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

There are published recommendations regarding best practice in swallowing assessment during the COVID-19 pandemic. Understandably, early guidelines were largely focused on staff safety. There is published agreement on the need for PPE and consideration of risk to staff when considering instrumental swallowing evaluations. However, when considered carefully, current literature leaves practitioners with conflicting information about how to deliver best practice during this challenging time given that the gold standards for swallowing assessment are also those procedures that place our clinicians at the highest risk of transmission. Many early studies were descriptive in nature. This study is the first to provide data to support the fact that it is safe to return to the evidence-based practice of objective swallowing evaluations with appropriate PPE and clinical algorithms in place.

In mid-March 2020, in order to protect SLP staff, our department initially halted the use of instrumentation as did many acute care hospitals across the world. During this time, departmental and organizational focus was on acquisition of PPE and information about COVID- 19 transmission. Early advocacy for PPE in our department allowed our department to consider the possibility of resuming our evidence-based practice for swallow assessments—that is, any patient who fails a swallow screen receives an instrumental swallowing evaluation. Early in the process of resuming instrumentation, FEES and MBS evaluations required managerial approval. This process was a prioritization algorithm which allowed these procedures only for the most necessary of cases. After 6 months of implementation of the algorithm, knowledge of the virus had solidified and medical leadership had implemented institutional guidelines such that there was no longer a need for managerial approval for FEES. At this time, changes to the algorithm shifted to a more clinician based model where staff had increased autonomy in clinical decisions about when to conduct instrumental assessments. This algorithm continued to have strict PPE requirements and had parameters in place requiring results for COVID testing of patients prior to evaluation.

This clinical workflow is reflected in the data in Graphs 1 and 2 which demonstrate the evaluations completed during this time frame by month. These data accurately reflect clinical workflow at the time whereby there were zero FEES and 9 MBS completed in April of 2020, a small number (51 FEES and 16 MBS) in May 2020, and by June 2020, just three full months into the pandemic, the number of evaluations nearly tripled from the first month (161 FEES and 41 MBS). By August 2020, the number of evaluations reached 267 FEES and 38 MBS, nearing the average evaluations (275 FEES and 44 MBS) from July 2020–September 2021. The ability of our team to swiftly resume this level of service delivery was the result of early advocacy for appropriate PPE as well as investigative diligence in using available information to make safe decisions about the resuming objective swallowing evaluations.

The decision to advocate for return to this practice was evidence driven. In our institution, every patient eligible for a screen receives one. Those that pass, are placed on a diet and those that fail receive an objective swallowing assessment (FEES or MBS). Those patients that are not eligible for a swallow screen, for example, patients with pre-existing dysphagia, instead receive only the instrumental evaluation. Early in the pandemic, the cessation of objective evaluation made this evidence-based practice difficult. The ability to perform instrumental assessment on these patients is critical in order to obtain definitive information about dysphagia status, severity, and bolus flow characteristics that allow SLPs to diagnose and appropriately manage the dysphagia. SLPs at our institution, and across the country, were left struggling without the use of instrumentation to answer important questions about dysphagia status. While this shift likely impacted many, if not all SLPs, who assess dysphagia, our speech-language pathologists were left particularly conflicted as so many of our patients receive instrumental assessments on a regular basis. The use of non-instrumental assessment tools to make decisions about dysphagia is largely not well supported in the literature. For example, recommendations in the literature suggest that clinicians consider the use of a CSE as an alternative to instrumental assessment; however, the literature demonstrates many of the variables that clinicians use in a CSE to assess aspiration risk are not evidence based [12]. At our institution, the standard of care dictates the use of the Yale Swallow Protocol which has a sensitivity of 96.5% for detecting aspiration risk [13]. The sensitivity of the CSE is highly variable and lower than the YSP, with reported sensitivities ranging from 42 to 92% [14,15,16,17,18]. For this reason, a shift to the use of a CSE was not a desirable option for our staff, who were accustomed to using a validated tool with an excellent sensitivity. While the CSE is not the only recommended alternative, other recommended solutions raise similar concerns. The lack of evidence-based alternatives to objective assessment drove the decision to safely reinstitute objective assessment as early as possible in the pandemic.

While the decision to return to objective evaluations occurred rather early in the pandemic, it is important to note that a ‘business as usual’ approach was not embraced during this time. Thoughtful and carefully planned procedures for PPE and algorithms for clinical contact were in place. Additionally, careful consideration of clinical workflow with COVID-positive patients was taken into account and remains in place to date. For example, concern for staff safety shifted typical workflow on re-evaluation using objective assessment in COVID-positive patients. Even currently, repeat FEES on COVID-positive patients are completed more judiciously than on those without COVID-19 given the risk of transmission. These, and other measures, complemented the PPE requirements and decision making algorithms to ultimately result in a safe return to objective dysphagia assessment.

Limitations and Future Directions

While the sample size of the study reflects that of a busy, urban care tertiary care center during the study period, only a relatively small percentage of the study sample were COVID-positive patients. Thus, generalization of findings may be limited due to sample size and further investigation with a larger sample of COVID-positive patients would be a beneficial next step. Additionally, institutional policy dictated that vaccinated staff did not require weekly testing unless they were symptomatic or had exposure to someone with COVID-19. This creates an inherent limitation in that staff could have had asymptomatic infection and thus not been included in the study data.

Findings of this study indicate that it is safe to resume objective swallowing evaluations in hospitalized patients with proper PPE and protocols in place. The results of this study should serve as a foundation for a plethora of future research on the relationship between dysphagia and COVID-19. For example, this study did not compare pre-pandemic instrumental assessment data with current practice. This would be interesting to consider for future research. Additionally, future publication of more detailed information about the use of such clinical algorithms as the ones used during this study period could be beneficial as these details are beyond the scope of this investigation.

Conclusion

The purpose of this investigation was to determine the effects of the protocols put in place to safely assess dysphagia during the COVID-19 pandemic. Results indicate that a measured return to instrumental assessment was successful in our institution and, suggest that, with proper PPE and protocols in place, the field can resume safe, evidence-based, instrumental evaluations for dysphagia assessment. This knowledge is critically important as clinicians work to resume evidence-based practice for our patients in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Results of this study may serve as a foundation for advancing clinical practice and research in the care of our patients with dysphagia during these unprecedented times.

References

Lammers MJW, Lea J, Westerberg BD. Guidance for otolaryngology health care workers performing aerosol generating medical procedures during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Otolaryngol-Head Neck Surg. 2020;49(1):36–8.

Miles A, Connor NP, Desai RV, Jadcherla S, Allen J, Brodsky M, Garand KL, Malandraki GA, McCulloch TM, Moss M, Murray J, Pulia M, Riquelme LF, Langmore SE. Dysphagia care across the continuum: a multidisciplinary Dysphagia Research Society taskforce report of service-delivery during the COVID-19 Global Pandemic. Dysphagia. 2020;36(2):170–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-020-10153-8.

Bolton L, Brady G, Coffey M, Haines J, Roe J, Wallace S. Speech and language therapist-led endoscopic procedures in the COVID-19 pandemic. R Coll Speech Lang Ther. 2020;1(8):1–17.

Brodsky MB, Gilbert RJ. The long-term effects of COVID-19 on dysphagia evaluation and treatment. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2020;101(9):1662–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2020.05.006.

Muraleedharan M, Kaur S, Arora K, Singh Virk RS. Otolaryngology practice in Covid 19 Era: a road-map to safe endoscopies. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020;73(1):101–3.

Bolton L, Mills C, Wallace S, Brady MC. Aerosol generating procedures, dysphagia assessment and COVID-19: a rapid review. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2020;55(4):629–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12544.

Guda NM, Emura F, Reddy DN, Rey J, Seo D, Gyokeres T, Tajiri H, Faigel D. Recommendations for the operation of endoscopy centers in the setting of the COVID-19 pandemic—World Endoscopy Organization guidance document. Dig Endosc. 2020;32(6):844–50.

Namasivayam-MacDonald AM, Riquelme LF. Speech-language pathology management for adults with COVID-19 in the acute hospital setting: initial recommendations to guide clinical practice. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 2020;29(4):1850–916. https://doi.org/10.1044/2020_AJSLP-20-00096.

Mattei A, Amy de la Bretèque B, Crestani S, Crevier-Buchman L, Galant C, Hans S, Julien-Laferrière A, Lagier A, Lobryeau C, Marmouset F, Robert D, Woisard V, Giovanni A. Guidelines of clinical practice for the management of swallowing disorders and recent dysphonia in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2020;137(3):173–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anorl.2020.04.011.

Frajkova Z, Tedla M, Tedlova E, Suchankova M, Geneid A. Postintubation dysphagia during COVID-19 outbreak-contemporary review. Dysphagia. 2020;35(4):549–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-020-10139-6.

Fritz MA, Howell RJ, Brodsky MB, Suiter DM, Dhar SI, Rameau A, Richard T, Skelley M, Ashford JR, O’Rourke AK, Kuhn MA. Moving forward with dysphagia care: implementing strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. Dysphagia. 2020;36(2):161–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-020-10144-9.

McCullough GH, Wertz RT, Rosenbek JC, Dinneen C. Clinicians’ preferences and practices in conducting clinical/bedside and videofluoroscopic swallowing examinations in an adult, neurogenic population. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 1999;8:149–63.

Leder SB, Suiter DM. The Yale Swallow Protocol: an evidence-based approach to decision making. New York: Springer; 2014. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-05113-0.

McCullough GH, Rosenbek JC, Wertz RT, McCoy S, Mann G, McCullough K. Utility of clinical swallowing examination measures for detecting aspiration post-stroke. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2005;48:1288–93.

Moss M, White SD, Warner H, Dvorkin D, Fink D, Gomez-Taborda S, Higgins C, Krisciunas GP, Levitt JE, McKeehan J, McNally E, Rubio A, Scheel R, Siner JM, Vojnik R, Langmore SE. Development of an accurate bedside swallowing evaluation decision tree algorithm for detecting aspiration in acute respiratory failure survivors. Chest. 2020;158(5):1923–33.

Daniels SK, McAdam CP, Brailey K, Foundas AL. Clinical assessment of swallowing and prediction of dysphagia severity. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 1997;6(4):17.

Logemann JA, Veis S, Colangelo L. A screening procedure for oropharyngeal dysphagia. Dysphagia. 1999;14(1):44–51.

Splaingard M, Hutchins B, Sulton L, Chaudhuri G. Aspiration in rehabilitation patients: videofluoroscopy vs bedside clinical assessment. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1988;69(8):637.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Jennifer Coutinho for her contribution of the clinical algorithms and to the clinical staff of Yale New Haven Hospital for providing the care that made this research possible. The authors would like to thank Caitlin Partridge at JDAT-Research, YCCI at Yale University School of Medicine for electronic medical record data acquisition and unwavering support of this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix 1

Appendix 1

Algorithm A: Initial Clinical Workflow of Study Period.

Algorithm B: Final Clinical Workflow of Study Period. *PUI (person under investigation): patient with undetermined COVID status, same as rule out patient.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Warner, H., Young, N. Best Practice in Swallowing Assessment in COVID-19. Dysphagia 38, 397–405 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-022-10478-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-022-10478-6